Background:

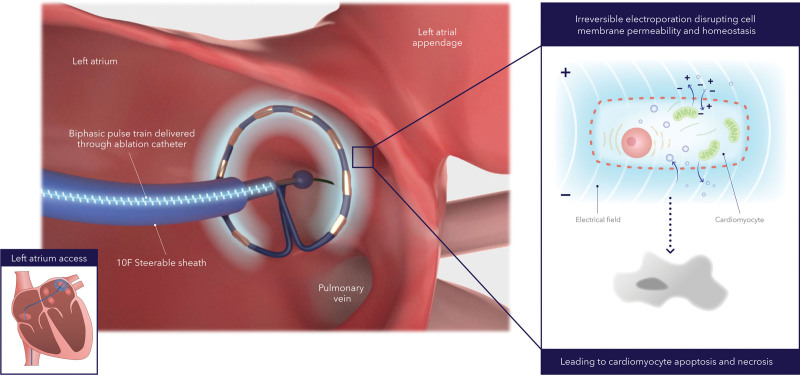

Pulsed field ablation uses electrical pulses to cause nonthermal irreversible electroporation and induce cardiac cell death. Pulsed field ablation may have effectiveness comparable to traditional catheter ablation while preventing thermally mediated complications.

Methods:

The PULSED AF pivotal study (Pulsed Field Ablation to Irreversibly Electroporate Tissue and Treat AF) was a prospective, global, multicenter, nonrandomized, paired single-arm study in which patients with paroxysmal (n=150) or persistent (n=150) symptomatic atrial fibrillation (AF) refractory to class I or III antiarrhythmic drugs were treated with pulsed field ablation. All patients were monitored for 1 year using weekly and symptomatic transtelephonic monitoring; 3-, 6-, and 12-month ECGs; and 6- and 12-month 24-hour Holter monitoring. The primary effectiveness end point was freedom from a composite of acute procedural failure, arrhythmia recurrence, or antiarrhythmic escalation through 12 months, excluding a 3-month blanking period to allow recovery from the procedure. The primary safety end point was freedom from a composite of serious procedure- and device-related adverse events. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to evaluate the primary end points.

Results:

Pulsed field ablation was shown to be effective at 1 year in 66.2% (95% CI, 57.9 to 73.2) of patients with paroxysmal AF and 55.1% (95% CI, 46.7 to 62.7) of patients with persistent AF. The primary safety end point occurred in 1 patient (0.7%; 95% CI, 0.1 to 4.6) in both the paroxysmal and persistent AF cohorts.

Conclusions:

PULSED AF demonstrated a low rate of primary safety adverse events (0.7%) and provided effectiveness consistent with established ablation technologies using a novel irreversible electroporation energy to treat patients with AF.

Registration:

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT04198701.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, catheter ablation, clinical trial, electroporation, pulsed field ablation

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Irreversible electroporation is a novel, nonthermal method for cardiac ablation that can improve the safety and efficiency of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation.

This trial showed that pulsed field ablation for atrial fibrillation achieved a freedom from procedural failure, arrhythmia recurrence, or escalation of antiarrhythmic drugs consistent with thermal ablation technologies.

This trial also demonstrated a very low incidence of procedure-related adverse events with no pulmonary vein stenosis, phrenic nerve injury, or esophageal injury.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Pulsed field ablation, using irreversible electroporation, will likely provide a more efficient and safe method for catheter ablation of both paroxysmal and persistent arial fibrillation.

Efficacy of pulsed field ablation for atrial fibrillation appears consistent with that of traditional thermal methods of ablation.

Editorial, see p 1433

Catheter ablation is an effective treatment for patients with symptomatic, drug-refractory atrial fibrillation (AF).1,2 Traditional thermal ablation may be complicated by adverse events such as esophageal injury, phrenic nerve injury, and pulmonary vein stenosis.3 In contrast, pulsed field ablation creates lesions in cardiac tissue nonthermally and within milliseconds through the mechanism of irreversible electroporation.4,5 As cardiac cells are exposed to high electric field gradients, their cell membranes undergo increased permeability, leading to cell death without substantial protein denaturation or tissue scaffolding damage.6 Other cell types (eg, esophagus and nerves) are more resistant to such changes. Acute clinical results demonstrated that pulsed field ablation can achieve pulmonary vein isolation without collateral damage in a time-efficient manner.7 The PULSED AF pivotal study (Pulsed Field Ablation to Irreversibly Electroporate Tissue and Treat AF) was performed to evaluate the 12-month effectiveness and safety of a novel pulsed field ablation system in a population of patients with paroxysmal or persistent symptomatic AF.

Methods

All supporting data are available within the article and its Supplemental Material.

Trial Design

The PULSED AF trial was a prospective, global, multicenter, nonrandomized, paired single-arm trial to evaluate a pulsed field ablation system (PulseSelect Pulsed Field Ablation System; Medtronic) for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF. The steering committee was responsible for design, execution, and study oversight (Appendix in the Supplemental Material). At each center, local ethics review committees approved the study, which was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The sponsor was not involved in adjudicating effectiveness or safety events. Primary safety end point events were adjudicated by an independent clinical events committee (Appendix in the Supplemental Material), and arrhythmia monitoring events were adjudicated by a core laboratory. An independent data monitoring committee reviewed accumulating data to protect the interests of patients and monitor the overall conduct of the study. The original protocol was conceived, designed, and written by the sponsor and then refined with input from the steering committee and the US Food and Drug Administration. Data analysis was performed by the sponsor, and data interpretation was provided by the principal investigator, Dr Atul Verma, and the steering committee. All steering committee members approved data analyses and interpretation, article contents, and the decision to publish. All authors vouch for the completeness, fidelity, and accuracy of the study protocol and data.

Study Participants

Patients with recurrent symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent AF who failed or did not tolerate treatment with ≥1 class I or III antiarrhythmic drugs were treated at 41 centers in 9 countries and treated by 67 different operators, 61 of whom had not used the system in the PULSED AF pilot trial (Appendix in the Supplemental Material). Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table S3. All patients provided written informed consent.

Procedure

Ablation methods are described in the Appendix in the Supplemental Material and a previous publication.7 Before the ablation, patients were on continuous, uninterrupted oral anticoagulation therapy for at least 3 weeks. Antiarrhythmic drugs were not required to be stopped before ablation. During the ablation procedure, using a percutaneous, transvenous approach, operators performed transseptal puncture and introduced the catheter into the left atrium over a guidewire. Heparin was administered before or immediately after transseptal puncture, or both, and sustained throughout the procedure to maintain activated clotting time levels of ≥350 seconds, with monitoring every 15 to 30 minutes for the duration of the procedure. The circular array of the pulsed field ablation catheter was positioned at each pulmonary vein ostium, as assessed by fluoroscopy or intracardiac echocardiography imaging (Figure 1). One application was defined as 4 biphasic, bipolar pulse trains, each lasting 100 to 200 ms at 1400 to 1500 V measured from baseline to peak (2800 to 3000 V measured peak to peak). After each application, the catheter was rotated circumferentially to a new position to achieve full circumferential isolation. This workflow was based on previous acute clinical work with the same system, demonstrating that overlapping lesion sets from an ostial to wide antral pulmonary vein position optimized full pulmonary vein isolation.7 Electrical isolation was assessed by entrance block testing after a protocol-mandated 20-minute wait period with the operator’s preferred catheter. Use of an esophageal luminal temperature probe was optional. No system or waveform modifications were made during the trial.

Figure 1.

Catheter ablation method with pulsed field ablation system. Alternating positive and negative electrodes sustains a bipolar electrical field around the catheter that extends into the tissue. The electrical field increases cell membrane permeabilization, which then leads to cell function disruption and eventually to cell death (ie, apoptosis and necrosis).

Study Follow-Up

All patients were monitored for 12 months with weekly and symptomatic transtelephonic monitoring; 3-, 6-, and 12-month 12-lead ECGs; and 6- and 12-month 24-hour Holter monitoring. Additional follow-up visits occurred virtually or in-person at 7 days, 30 days, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after the index ablation procedure.

Substudies

All sites approached patients sequentially, and those who consented underwent cardiac computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at baseline and 3 months after ablation to detect the incidence of pulmonary vein stenosis for up to 50 patients (protocol in the Appendix in the Supplemental Material). An independent core laboratory adjudicated pulmonary vein stenosis diameters as moderate (50% to 70%) or severe (≥70%) reduction.1

Sites with a 1.5T MRI approached patients sequentially, and those who consented underwent cerebral MRI before and after ablation to detect the incidence of silent cerebral lesions as well as Mini-Mental State Examination for up to 50 patients (protocol in the Appendix in the Supplemental Material). All silent cerebral lesions were identified by 2 independent neuroradiologists.8–10

End Points

The primary effectiveness end point was freedom from a composite end point of acute procedural failure, arrhythmia recurrence, or antiarrhythmic escalation through 12 months, excluding an initial 90-day blanking period to allow procedural recovery. Acute procedural failure was defined as an inability to isolate all pulmonary veins or any ablation in the left atrium using a nonstudy device during the index procedure. Other components of the end point included any of the following events after the 90-day blanking period: (1) documented atrial arrhythmia recurrence of ≥30 seconds; (2) any subsequent AF surgery or ablation in the left atrium, excluding one repeat pulsed field ablation within the 90-day blanking; (3) direct current cardioversion for atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence; (4) a class I or III antiarrhythmic drug dose increase from the historic maximum ineffective dose before the ablation procedure; (5) initiation of a new class I or III antiarrhythmic drug; or (6) during the blanking period, initiation of or use of amiodarone at a dose greater than the maximum previous ineffective dose. Within the first 90 days after ablation, recurrent arrhythmias could be managed with antiarrhythmic drugs, cardioversion, or repeat pulsed field ablation without penalty to the primary effectiveness end point.

The primary safety end point was freedom from a composite of serious procedure- and device-related adverse events. Serious adverse events were prespecified, and their relatedness to the pulsed field ablation system or procedure was adjudicated by the clinical events committee. Sites were required to report all adverse events. All adverse events were collected in adherence to ISO 14155:2020.11

Prespecified secondary end points included quality of life as assessed by the Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life (AFEQT) and European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaires (Appendix in the Supplemental Material).12–14 Additional prespecified ancillary end points presented include procedural measures.

Statistical Analysis

Prespecified performance goals were set at >50% and >40% for paroxysmal and persistent AF cohorts as defined by the international consensus statement.1 The prespecified safety performance goal of <13% was guided by the US Food and Drug Administration (Appendix in the Supplemental Material). To calculate sample size, using a 1-sided α of 0.025, simulation methods were used. In both cohorts, we assumed that 68% of patients in the paroxysmal AF cohort and 54% of patients in the persistent AF cohort would have treatment success, and that 5% of patients in each group would have a primary safety end point event. On the basis of these assumptions, sample sizes of 90 patients with paroxysmal and 150 with persistent AF were calculated to be sufficient to provide ≥90% power for the analysis of the primary effectiveness end point in each cohort. For the primary safety end point, 138 participants in each group provided 90% power for the analysis. Therefore, a sample size of 150 was selected for each cohort.

All primary analysis patients who underwent pulsed field ablation were included in all analyses unless data were missing. Missing data were not imputed. The primary effectiveness end point was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier analysis. Time 0 was defined as the date of ablation, and data were censored at the patients’ 12-month follow-up or exit from the trial. The start date for assessing atrial arrhythmia was 91 days after time 0. The standard error for each percentage of patients with an event within 12 months was approximated with the Greenwood formula and 2-sided log–log CIs were constructed comparing against the prespecified performance goals. The primary safety end point was analyzed with the use of Kaplan-Meier survival analysis.

Changes in quality of life were evaluated using the paired t test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Adjustment for multiple comparisons in analyses of secondary end points was performed using the Hochberg procedure. All analyses were conducted with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Patients

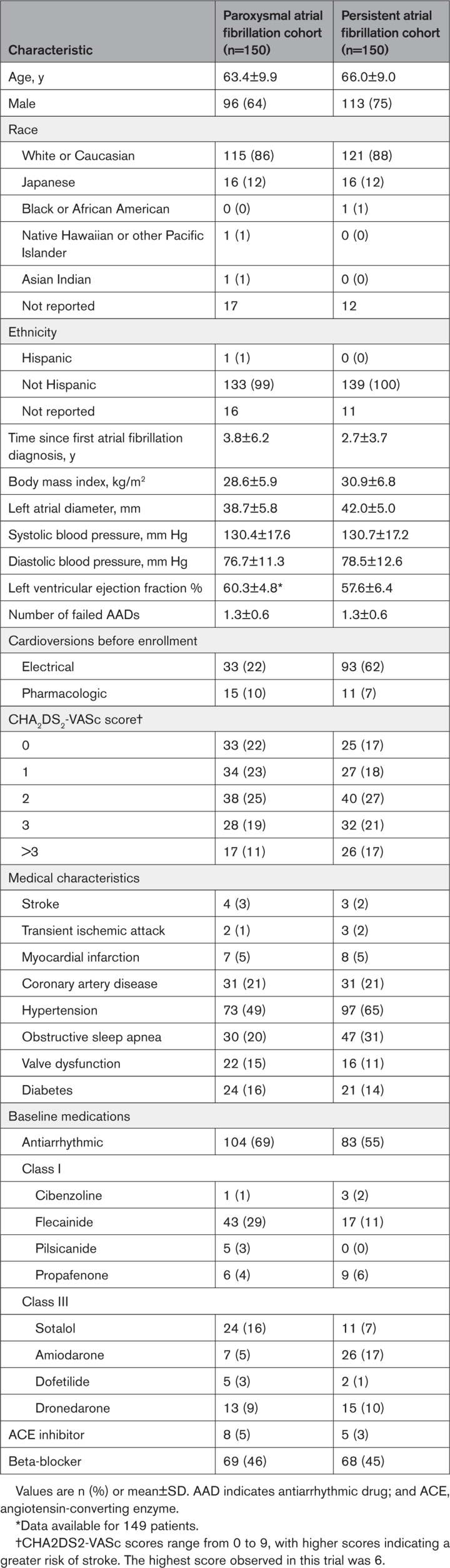

A total of 383 patients were enrolled between March 2021 and November 2021; 300 were included in the primary analysis cohort, with an average of 5.8 patients treated per operator. Patient flow is shown in Figure S1. In total, 146 of 150 (97%) patients with paroxysmal AF and 141 of 150 (94%) patients with persistent AF completed follow-up. Overall, 5887 transtelephonic transmissions from patients with paroxysmal AF and 5974 transmissions from patients with persistent AF after the 90-day blanking period were received and reviewed. Adherence to Holter, ECG, and scheduled transtelephonic transmission during the 12 months for both cohorts was 86%, 90%, and 81%, respectively. Baseline characteristics are presented for paroxysmal and persistent AF cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

Procedural Characteristics

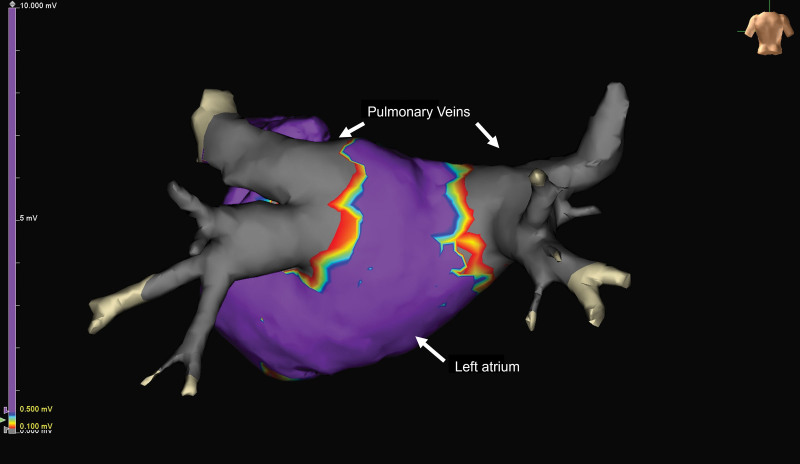

During the procedure, acute pulmonary vein isolation was achieved with the investigational device in 100% of pulmonary veins in the paroxysmal AF cohort and 100% of pulmonary veins in the persistent AF cohort (Figure 2). Two acute procedural failures occurred in the persistent cohort resulting from use of a nonstudy device to ablate left atrial structures outside of the pulmonary veins.

Figure 2.

Postablation voltage map of left atrium. The map demonstrates acute pulmonary vein isolation. Gray areas represent ablated or electrically isolated tissue around the 4 pulmonary veins.

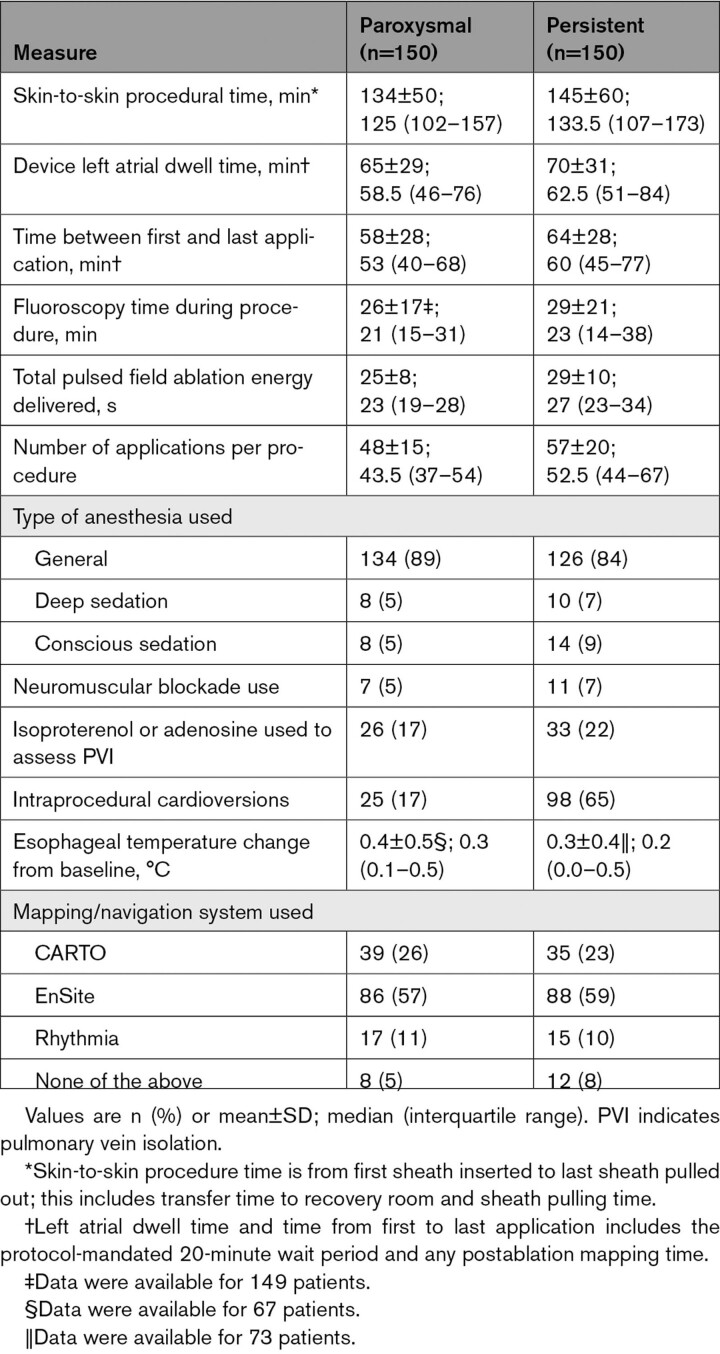

Procedural details are presented in Table 2. The mean time between first and last application was 58±28 minutes and 64±28 minutes for the paroxysmal and persistent AF cohorts, respectively. The time between first and last application included the 20-minute, protocol-mandated waiting period and postablation mapping time. Mapping systems were used in 95% of paroxysmal and 92% of persistent AF procedures (Figure 2). Overall, 25±8 seconds and 29±10 seconds of pulsed field ablation energy were delivered per paroxysmal and persistent AF procedure, respectively. General anesthesia or deep sedation was used in 95% and 91% of paroxysmal and persistent AF procedures, respectively.

Table 2.

Procedural Characteristics

Primary Effectiveness and Safety End Points

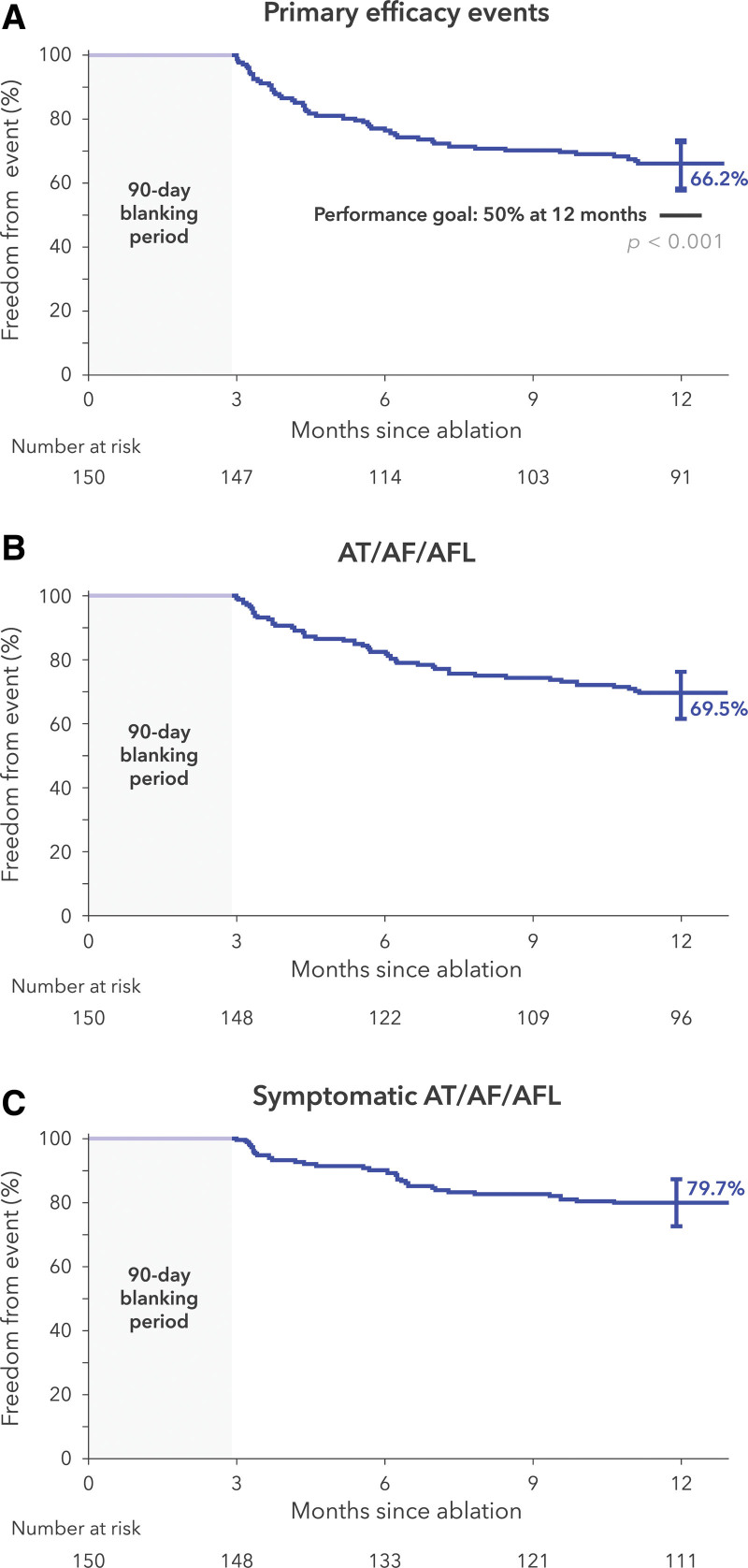

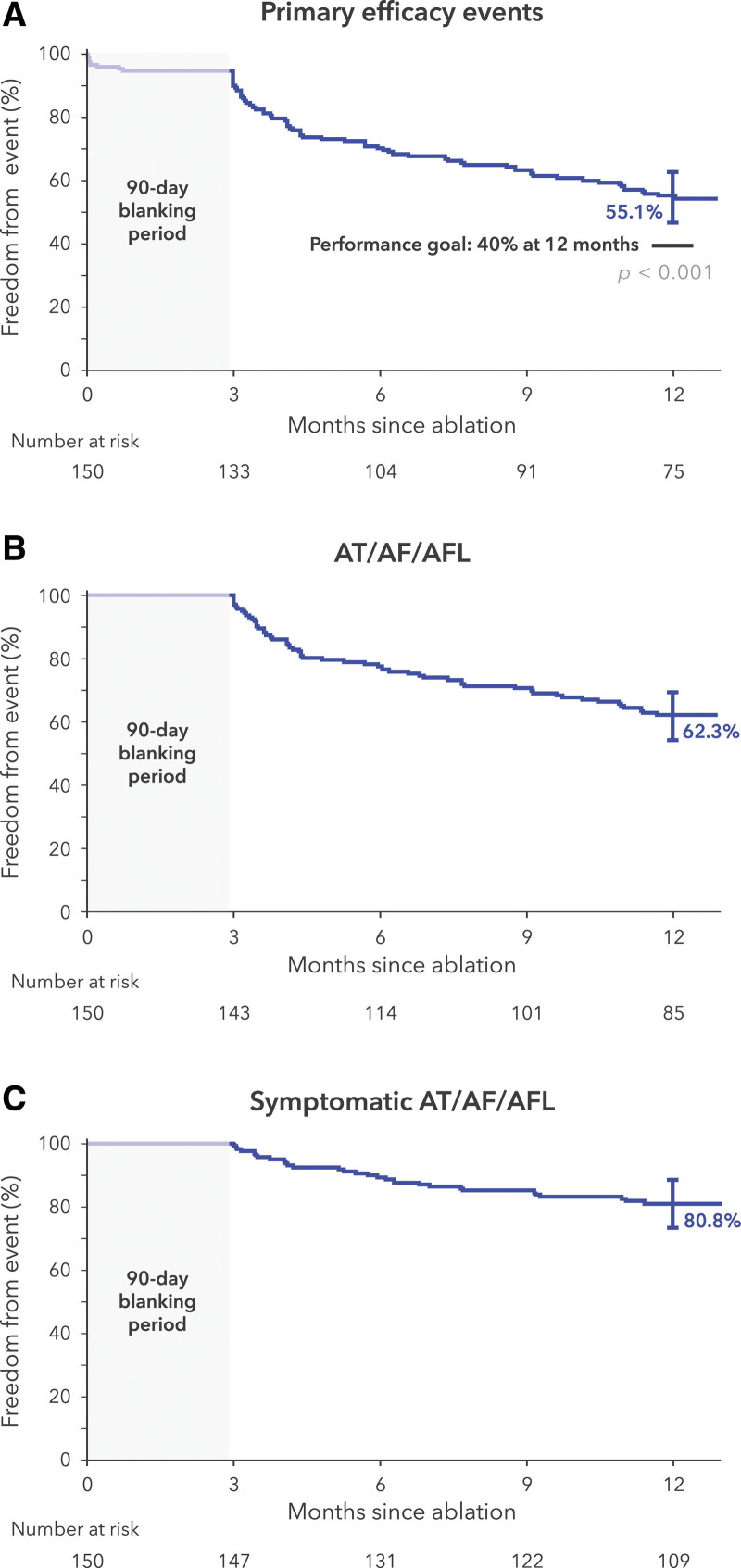

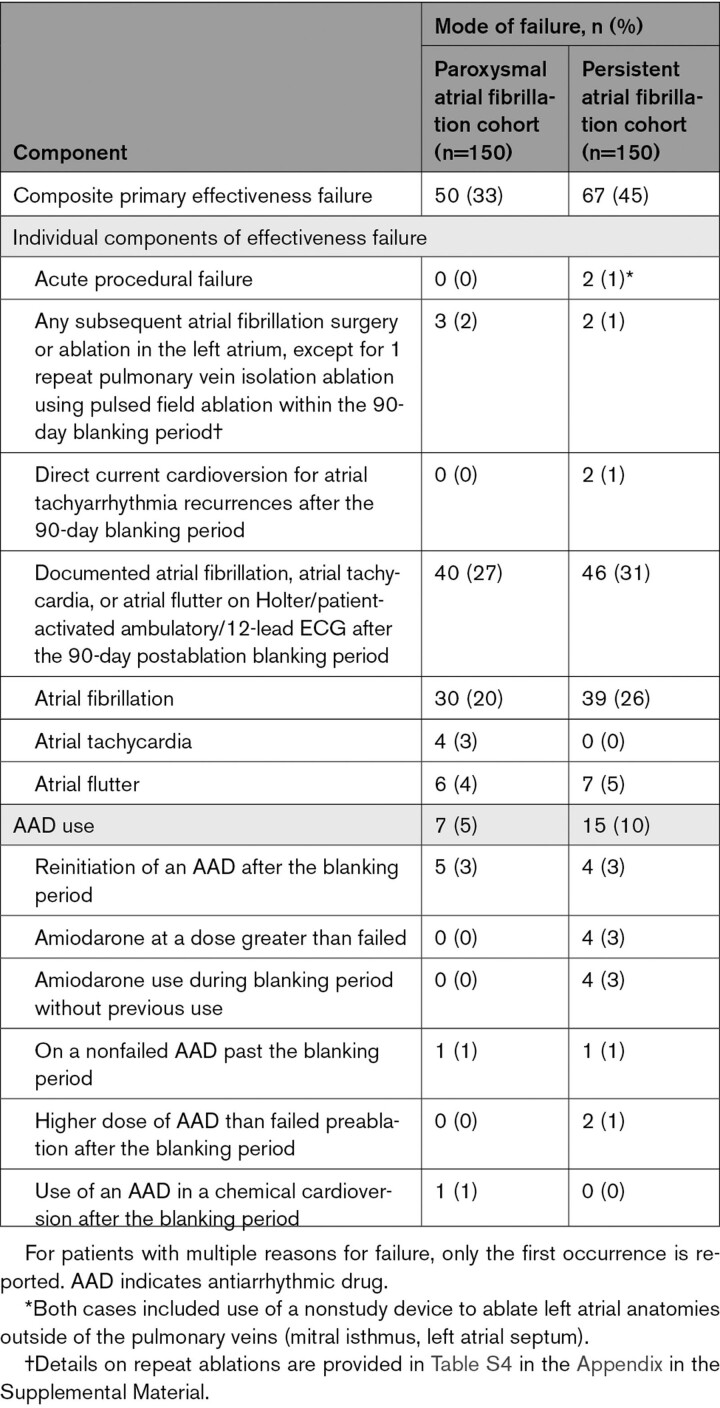

Treatment success occurred in 100 patients in the paroxysmal AF cohort and 83 patients in the persistent AF cohort (1-year Kaplan-Meier estimates, 66.2% [95% CI, 57.9 to 73.2] and 55.1% [95% CI, 46.7 to 62.7], respectively; Figure 3A and Figure 4A). The individual components of effectiveness failure are specified in Table 3. A total of 8% of patients with paroxysmal AF and 9% of patients with persistent AF underwent repeat ablation outside of the blanking period (Table S4). During the blanking period, 6 patients with persistent AF had treatment failure attributable to amiodarone use.

Figure 3.

Treatment success at 12 months for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. A, Primary end point of the study. B, Any atrial tachyarrhythmia found on a Holter, ECG, or transtelephonic monitor after the blanking period is considered an event. C, Any atrial tachyarrhythmia found on a transtelephonic monitor and accompanied by patient-reported symptoms is an event. The bars on the survival curves indicate 95% CIs. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; and AT, atrial tachycardia.

Figure 4.

Treatment success at 12 months for persistent atrial fibrillation. A, Primary end point of the study. B, Any atrial tachyarrhythmia found on a Holter, ECG, or transtelephonic monitor after the blanking period is considered an event. C, Any atrial tachyarrhythmia found on a transtelephonic monitor and accompanied by patient-reported symptoms is an event. The bars on the survival curves indicate 95% CIs. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; and AT, atrial tachycardia.

Table 3.

Primary Effectiveness End Point Summary

Freedom from any atrial arrhythmia recurrence after the 90-day blanking period was 69.5% and 62.3% in the paroxysmal and persistent AF cohorts, respectively (Figure 3B and Figure 4B). Freedom from recurrence of any symptomatic atrial arrhythmias, as documented on transtelephonic monitoring, was 79.7% and 80.8% in the paroxysmal and persistent AF cohorts, respectively (Figure 3C and Figure 4C).

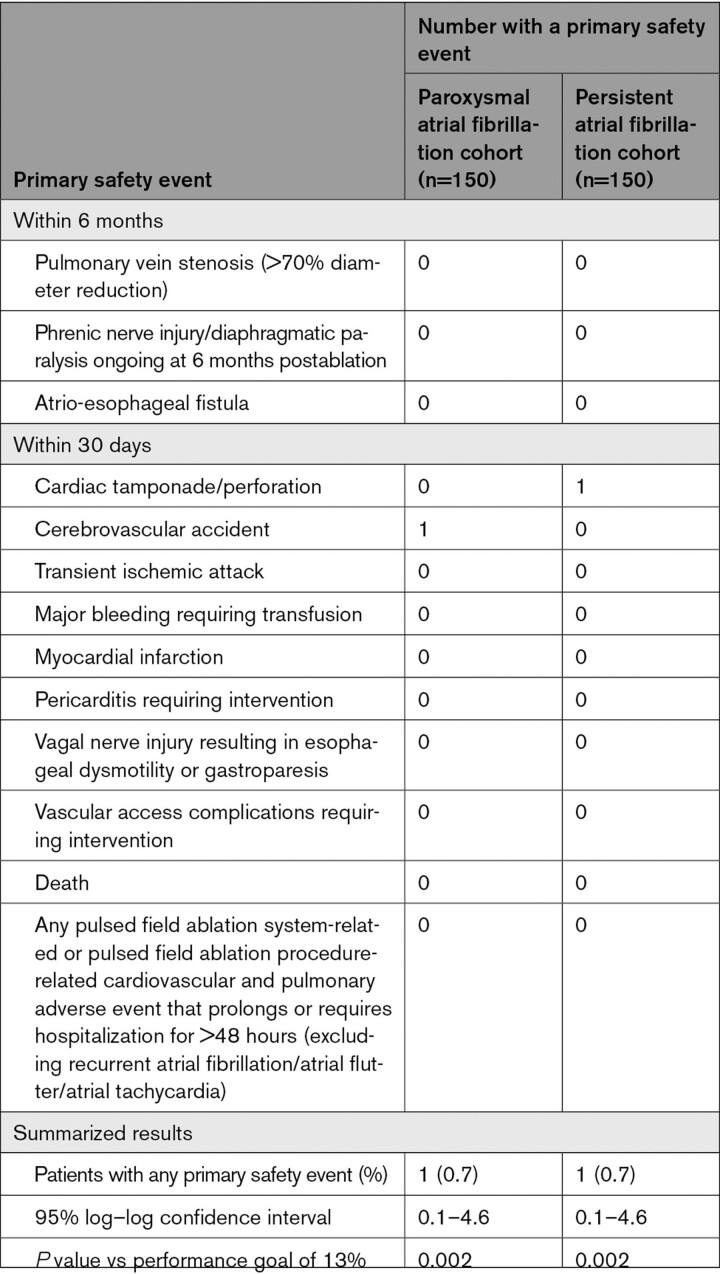

The primary safety end point occurred in 1 patient with paroxysmal AF and 1 patient with persistent AF (6-month Kaplan-Meier event rate estimates, 0.7% [95% CI, 0.1 to 4.6] and 0.7% [95% CI, 0.1–4.6], respectively; Table 4). One cerebrovascular accident occurred on the same day as the procedure in a patient with paroxysmal AF (with left lower leg numbness and mild dysphasia) and was resolving at the conclusion of the study. One pericardial effusion requiring drainage occurred after pulmonary vein isolation in a patient with persistent AF. After the ablation, 1 death occurred in each cohort during the follow-up period: in the paroxysmal AF cohort, 1 patient with a history of cirrhosis and a CT scan demonstrating liver masses died of liver failure; in the persistent AF cohort, 1 patient died of cardiopulmonary arrest within 2 weeks after dofetilide was initiated. No other reports of death, atrio-esophageal fistula, other esophageal injury, myocardial infarction, severe pulmonary vein stenosis, or phrenic nerve injury related to the pulsed field ablation procedure were reported. Other important adverse events, such as coronary artery spasm or incidental ST-segment elevation, were not detected.

Table 4.

Primary Safety End Point Summary

Secondary End Points

Compared with baseline, improvement in postablation quality of life was statistically significant (Table S5). AFEQT score improved by a mean of 29.4 (95% CI, 25.8–33.1) and 29.0 (95% CI, 25.5–32.5) points from baseline to 12 months in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF, respectively. At 12 months, the EQ-5D-5L score improved by 0.05 points (95% CI, 0.02–0.08) in patients with paroxysmal AF and 0.06 points (95% CI, 0.04–0.09) in patients with persistent AF. For both measures, this is considered a meaningful improvement.13,14

Among 45 patients who underwent cerebral MRI before and after ablation at 15 centers, 4 (8.9%) had a new, postprocedural silent cerebral lesion (Table S6). There was negligible change (0.4±1.8) in Mini-Mental State Examination scores before (28.8±1.3) and after ablation (29.2±1.4) in the cohort. No moderate or severe pulmonary vein stenosis was observed between baseline and 3-month imaging performed on 63 patients (Table S7). Optional esophageal temperature monitoring demonstrated a 0.3±0.4°C overall change in esophageal temperature from baseline in 140 patients (Table 2).

Discussion

In this global, multicenter, prospective paired single-arm trial, we demonstrated the ability of pulsed field ablation to treat both paroxysmal and persistent AF with catheter ablation. Acute isolation was demonstrated in 100% of all pulmonary veins. The freedom from treatment failure rates reported in this study were consistent with thermal ablation (radiofrequency and cryoablation).15,16 The primary safety adverse event rate was excellent, with a 0.7% rate of major complications overall and no occurrence of phrenic, esophageal, or pulmonary vein injury. In addition, we demonstrated a meaningful, statistically significant improvement in quality of life from baseline.13,14 The study had a very high compliance with follow-up and rigorous arrhythmia monitoring. This is the first multicenter, global prospective clinical trial evaluating any investigational pulsed field ablation system with predefined end points approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. In contrast to previously published pulsed field ablation studies, the primary effectiveness end point reported here included freedom from a composite of multiple failure modes, and the study was executed globally with rigorous monitoring techniques, specifically weekly and symptomatic transtelephonic monitoring combined with Holter monitoring every 6 months.

Catheter ablation is an effective intervention for AF. Thermal modes of ablation (eg, radiofrequency and cryoablation) have performed reasonably for years, but are limited by the potential for collateral tissue damage (eg, esophagus and phrenic nerve) and long application times (seconds to minutes).16,17 By leveraging a rapid, nonthermal mechanism of cell death, pulsed field ablation can improve the efficiency, safety, and possibly effectiveness of cardiac ablation.

Pulsed field energy can be delivered within milliseconds and substantially improves procedural efficiency. In this study, total energy application time was ≈30 seconds, and the time from first to last application was ≈1 hour. This is despite the large, global nature of the trial, with 67 different operators across 9 countries, 87% of whom treated <10 patients and the majority not having used the catheter before the study. If one subtracts the mandated 20-minute wait, the procedures could be completed in <1 hour.

Although esophageal, phrenic, and pulmonary vein injuries are uncommon, the risk remains in 0.5% to 5% of patients receiving thermal ablation.18 Preclinical data have suggested that cardiac cells are preferentially affected by pulsed field ablation compared with pulmonary venous tissue and esophageal or myelinated nerve cells.4,19–21 Intentional overablation of these collateral tissues with pulsed fields preclinically failed to cause any substantial injury, and initial pilot human data were promising.7 This is the first prospective large-scale study to show a very low-risk profile of pulsed field ablation, even within a 41-center setting with multiple operators; other pulsed field ablation studies with >100 patients have reported major complication rates, from 1.5% to 3.3%, or low rates within single-center studies.21–24 In this study, the total risk of primary safety adverse events was <1%, with no indication of pulmonary vein, esophageal, or phrenic damage. Furthermore, silent cerebral risk was in keeping with other forms of ablation, which have reported rates of 4% to 10% for cryoablation and 0% to 19% for radiofrequency ablation.25–28 Similar to other catheter ablation studies, the rates of silent cerebral lesions were not correlated with neuropsychological decline.9 There was no incidence of unusual adverse events such as coronary artery spasm or ablation-associated ST-segment elevation related to the procedure.22,29

Our study demonstrates clinical effectiveness consistent with thermal catheter ablation from other large studies with similarly rigorous monitoring (eg, weekly transtelephonic monitoring). The FIRE AND ICE randomized clinical trial (FIRE AND ICE: Comparative Study of Two Ablation Procedures in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation; URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT01490814) reported 64% (radiofrequency) and 65% (cryoablation) outcomes in a paroxysmal cohort.16 Large persistent AF studies such as STOP Persistent AF (URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT03012841) and STAR-AF II (Substrate and Trigger Ablation for Reduction of Atrial Fibrillation Trial Part II; URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT01203748) reported effectiveness rates of 50% to 55%.15,30 The PULSED AF results are consistent with preclinical data showing that pulsed field ablation lesion depths are similar to thermal lesions.31

Differences in clinical study execution and end points make it challenging to provide direct comparisons of pulsed field ablation technologies. Some studies suggested better efficacy with pulsed field ablation, but these were pilot studies with surrogate outcomes or limited-center studies without robust arrhythmia monitoring.21,23,24,32,33 One large pulsed field ablation registry showed lower success compared with early pilot data.22,23,32,33 Only 1 pulsed field ablation study has published results with robust arrhythmia monitoring such as weekly transtelephonic transmissions, but 20% of the published 121-patient cohort did not reach 12-month follow-up, and 32% underwent a repeat ablation at any time during the study.23,33 As numerous pulsed field ablation systems are being developed with unique characteristics, future research may better elucidate differences in clinical performance of these systems.

This trial, like others, also used the 30-second cutoff of any atrial arrhythmia, irrespective of symptoms for defining recurrence, even though that may have limited clinical significance. Clinical success was also assessed in both patient populations on the basis of freedom from symptomatic arrhythmia recorded by weekly transtelephonic transmissions. Previous clinical studies have demonstrated an 80% clinical success rate at 15 months with established catheter ablation technologies, and this study reports a similar clinical success rate of 80% (paroxysmal) and 81% (persistent).1 Furthermore, the low (<10%) postblanking-period repeat ablation rate and clinically significant improvement in quality of life was also on par with reports from established ablation technologies.15,34 If pulsed field ablation can deliver similar effectiveness more efficiently and with fewer complications as operator experience with the technology increases, it will be a major advancement in catheter ablation. Longer-term studies, including assessments of durability upon repeat ablation, and randomized trials are needed to better understand pulsed field ablation technologies.

This trial has limitations. It was a single-arm design, although predefined performance goals were guided by a 2017 international consensus statement on catheter ablation.1 Furthermore, historical trials with similar monitoring methods allow for some indirect comparison. Establishing safety end points in new trials can be challenging because some complications, such as atrio-esophageal fistula, happen very rarely (0.02% to 0.11%).1,3 Endoscopic visualization could have confirmed the absence of esophageal erosions or ulcerations that may progress to fistula formation. However, we did not observe any clinical signs of esophageal injury, such as spasm or dysphagia, nor did we see any esophageal temperature rise.34 The majority of the trial participants were White, which does not represent the global diversity of the AF population, but is closer to insurance database rates observed in the United States.35,36 In addition, catheter design and waveform modifications in the future could improve effectiveness beyond what is available currently.

This global trial confirmed a low rate of serious procedure-related adverse events, a high rate of freedom from atrial arrhythmia recurrence, a clinically significant improvement in quality of life from baseline, and efficient procedure times with use of pulsed field ablation technology.

Article Information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the PULSED AF (Pulsed Field Ablation to Irreversibly Electroporate Tissue and Treat AF) sites and their dedicated staff, Jennifer Diouf, Josh Treadway, Rachel Siciliano, Mark Stewart, and the PULSED AF team from Medtronic.

Sources of Funding

This study was fully funded by Medtronic Inc.

Disclosures

Drs Verma, Boersma, Calkins, Haines, Hindricks, Kuck, Marchlinski, Natale, Packer, De Lurgio, and Sanders receive consultation funds from Medtronic, Inc. Dr Onal and J. Cerkvenik are employees of Medtronic, Inc. Dr Verma receives grants or consultation funds from Biosense Webster, Bayer, Medlumics, Adagio Medical, and Boston Scientific. Dr De Lurgio receives consultation or honoraria funds from Atricure and Boston Scientific. Dr Marchlinski receives grants, consultation, or honoraria funds from Biosense Webster, Abbott Medical, and Biotronik. Dr Sood receives consultation or honoraria funds from Johnson & Johnson, Boston Scientific, Atricure, Bristol Myers, and Pfizer. Dr Boersma receives consultation funds from Boston Scientific, Abbott Medical, Adagio Medical, Acutus Medical, and Philips Medical. Dr Kuck receives consultation funds from Cardiovalve. Dr Natale receives consultation funds from Abbott Medical, Baylis, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific. Dr Sanders receives grants or honoraria funds from Boston Scientific, Abbott Medical, Becton Dickenson, Pacemate, and CathRx. Dr Tada receives funds from Abbott Medical Japan LLC, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co Ltd, Daiichi Sankyo Company Ltd, Alvaus Inc, Biotronik Japan Inc, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Novartis Pharma KK. Dr Calkins receives consultation or honoraria funds from Boston Scientific, Abbott Medical, Atricure, and Biosense Webster.

Supplemental Material

Appendix

Expanded Methods

Tables S1–S7

Figure S1

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AF

- atrial fibrillation

- AFEQT

- Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life

- EQ-5D

- European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging

- PULSED AF

- Pulsed Field Ablation to Irreversibly Electroporate Tissue and Treat AF

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.063988.

Presented as an abstract at the Scientific Sessions of the American College of Cardiology, New Orleans, LA, March 4–6, 2023.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 1430.

Circulation is available at www.ahajournals.org/journal/circ

Continuing medical education (CME) credit is available for this article. Go to http://cme.ahajournals.org to take the quiz.

Contributor Information

David E. Haines, Email: dhaines@beaumont.edu.

Lucas V. Boersma, Email: l.boersma@antoniusziekenhuis.nl.

Nitesh Sood, Email: soodN@southcoast.org.

Andrea Natale, Email: dr.natale@gmail.com.

Francis E. Marchlinski, Email: Francis.Marchlinski@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

Hugh Calkins, Email: hcalkins@jhmi.edu.

Prashanthan Sanders, Email: prash.sanders@adelaide.edu.au.

Douglas L. Packer, Email: Crowson.Jacqueline@mayo.edu.

Karl-Heinz Kuck, Email: kakuHH@yahoo.com.

Gerhard Hindricks, Email: gerhard.hindricks@leipzig-ep.de.

Birce Onal, Email: birce.onal@medtronic.com.

Jeffrey Cerkvenik, Email: jeff.cerkvenik@medtronic.com.

Hiroshi Tada, Email: htada@u-fukui.ac.jp.

David B. DeLurgio, Email: ddelurg@emory.edu.

References

- 1.Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, Kim YH, Saad EB, Aguinaga L, Akar JG, Badhwar V, Brugada J, Camm J, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2018;20:e1–e160. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, Davies W, Iesaka Y, Kalman J, Kim YH, Klein G, Natale A, Packer D, et al. Updated worldwide survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety of catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:32–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.859116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart MT, Haines DE, Miklavčič D, Kos B, Kirchhof N, Barka N, Mattison L, Martien M, Onal B, Howard B, et al. Safety and chronic lesion characterization of pulsed field ablation in a porcine model. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2021;32:958–969. doi: 10.1111/jce.14980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yarmush ML, Golberg A, Sersa G, Kotnik T, Miklavcic D. Electroporation-based technologies for medicine: principles, applications, and challenges. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2014;16:295–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071813-104622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotnik T, Rems L, Tarek M, Miklavcic D. Membrane electroporation and electropermeabilization: mechanisms and models. Annu Rev Biophys. 2019;48:63–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-052118-115451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma A, Boersma L, Haines DE, Natale A, Marchlinski FE, Sanders P, Calkins H, Packer DL, Hummel J, Onal B, et al. First-in-human experience and acute procedural outcomes using a novel pulsed field ablation system: the PULSED AF pilot trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2022;15:e010168. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.121.010168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaita F, Caponi D, Pianelli M, Scaglione M, Toso E, Cesarani F, Boffano C, Gandini G, Valentini MC, De Ponti R, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a cause of silent thromboembolism? Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of cerebral thromboembolism in patients undergoing ablation of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2010;122:1667–1673. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.937953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deneke T, Jais P, Scaglione M, Schmitt R, L DIB, Christopoulos G, Schade A, Mügge A, Bansmann M, Nentwich K, et al. Silent cerebral events/lesions related to atrial fibrillation ablation: a clinical review. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26:455–463. doi: 10.1111/jce.12608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Greef Y, Dekker L, Boersma L, Murray S, Wieczorek M, Spitzer SG, Davidson N, Furniss S, Hocini M, Geller JC, et al. ; PRECISION GOLD investigators. Low rate of asymptomatic cerebral embolism and improved procedural efficiency with the novel pulmonary vein ablation catheter gold: Results of the precision gold trial. Europace. 2016;18:687–695. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Standardization Organization Technical Committee 194. Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects: good clinical practice. ISO 14155. 2020;3:1–83. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorian P, Burk C, Mullin CM, Bubien R, Godejohn D, Reynolds MR, Lakkireddy DR, Wimmer AP, Bhandari A, Spertus J. Interpreting changes in quality of life in atrial fibrillation: how much change is meaningful? Am Heart J. 2013;166:381–387.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes DN, Piccini JP, Allen LA, Fonarow GC, Gersh BJ, Kowey PR, O’Brien EC, Reiffel JA, Naccarelli GV, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Defining clinically important difference in the atrial fibrillation effect on quality-of-life score. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e005358. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coretti S, Ruggeri M, McNamee P. The minimum clinically important difference for eq-5d index: a critical review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14:221–233. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.894462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su WW, Reddy VY, Bhasin K, Champagne J, Sangrigoli RM, Braegelmann KM, Kueffer FJ, Novak P, Gupta SK, Yamane T, et al. ; STOP Persistent AF Investigators. Cryoballoon ablation of pulmonary veins for persistent atrial fibrillation: results from the multicenter STOP Persistent AF trial. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:1841–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuck KH, Brugada J, Fürnkranz A, Metzner A, Ouyang F, Chun KJ, Elvan A, Arentz T, Bestehorn K, Pocock SJ, et al. Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2235–2245. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1602014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrade JG, Champagne J, Dubuc M, Deyell MW, Verma A, Macle L, Leong-Sit P, Novak P, Badra-Verdu M, Sapp J, et al. ; CIRCA-DOSE Study Investigators. Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation assessed by continuous monitoring: a randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2019;140:1779–1788. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu L, Narasimhan B, Ho KS, Zheng Y, Shah AN, Kantharia BK. Safety and complications of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: predictors of complications from an updated analysis the national inpatient database. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2021;32:1024–1034. doi: 10.1111/jce.14979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howard B, Haines DE, Verma A, Kirchhof N, Barka N, Onal B, Stewart MT, Sigg DC. Characterization of phrenic nerve response to pulsed field ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2022;15:e010127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.121.010127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart MT, Haines DE, Verma A, Kirchhof N, Barka N, Grassl E, Howard B. Intracardiac pulsed field ablation: proof of feasibility in a chronic porcine model. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:754–764. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt B, Bordignon S, Tohoku S, Chen S, Bologna F, Urbanek L, Pansera F, Ernst M, Chun KRJ. 5s study: safe and simple single shot pulmonary vein isolation with pulsed field ablation using sedation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2022;15:e010817. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.121.010817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekanem E, Reddy VY, Schmidt B, Reichlin T, Neven K, Metzner A, Hansen J, Blaauw Y, Maury P, Arentz T, et al. ; MANIFEST-PF Cooperative. Multi-national survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety on the post-approval clinical use of pulsed field ablation (MANIFEST-PF). Europace. 2022;24:1256–1266. doi: 10.1093/europace/euac050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddy VY, Dukkipati SR, Neuzil P, Anic A, Petru J, Funasako M, Cochet H, Minami K, Breskovic T, Sikiric I, et al. Pulsed field ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: 1-year outcomes of IMPULSE, PEFCAT, and PEFCAT II. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021;7:614–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2021.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemoine MD, Fink T, Mencke C, Schleberger R, My I, Obergassel J, Bergau L, Sciacca V, Rottner L, Moser J, et al. Pulsed-field ablation-based pulmonary vein isolation: acute safety, efficacy and short-term follow-up in a multi-center real world scenario. Clin Res Cardiol. Published online September 22, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s00392-022-02091-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma A, Debruyne P, Nardi S, Deneke T, DeGreef Y, Spitzer S, Balzer JO, Boersma L; ERACE Investigators. Evaluation and reduction of asymptomatic cerebral embolism in ablation of atrial fibrillation, but high prevalence of chronic silent infarction: Results of the evaluation of reduction of asymptomatic cerebral embolism trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:835–842. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schilling R, Dhillon GS, Tondo C, Riva S, Grimaldi M, Quadrini F, Neuzil P, Chierchia GB, de Asmundis C, Abdelaal A, et al. Safety, effectiveness, and quality of life following pulmonary vein isolation with a multi-electrode radiofrequency balloon catheter in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: 1-year outcomes from shine. Europace. 2021;23:851–860. doi: 10.1093/europace/euaa382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halbfass P, Wielandts JY, Knecht S, Le Polain de Waroux JB, Tavernier R, De Wilde V, Sonne K, Nentwich K, Ene E, Berkovitz A, et al. Safety of very high-power short-duration radiofrequency ablation for pulmonary vein isolation: a two-centre report with emphasis on silent oesophageal injury. Europace. 2022;24:400–405. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura T, Kashimura S, Nishiyama T, Katsumata Y, Inagawa K, Ikegami Y, Nishiyama N, Fukumoto K, Tanimoto Y, Aizawa Y, et al. Asymptomatic cerebral infarction during catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: comparing uninterrupted rivaroxaban and warfarin (ascertain). JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4:1598–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy VY, Petru J, Funasako M, Kopriva K, Hala P, Chovanec M, Janotka M, Kralovec S, Neuzil P. Coronary arterial spasm during pulsed field ablation to treat atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2022;146:1808–1819. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verma A, Jiang CY, Betts TR, Chen J, Deisenhofer I, Mantovan R, Macle L, Morillo CA, Haverkamp W, Weerasooriya R, et al. ; STAR AF II Investigators. Approaches to catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1812–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howard B, Verma A, Tzou WS, Mattison L, Kos B, Miklavčič D, Onal B, Stewart MT, Sigg DC. Effects of electrode-tissue proximity on cardiac lesion formation using pulsed field ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2022;15:e011110. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.122.011110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy VY, Anic A, Koruth J, Petru J, Funasako M, Minami K, Breskovic T, Sikiric I, Dukkipati SR, Kawamura I, et al. Pulsed field ablation in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1068–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy VY, Neuzil P, Koruth JS, Petru J, Funosako M, Cochet H, Sediva L, Chovanec M, Dukkipati SR, Jais P. Pulsed field ablation for pulmonary vein isolation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lakkireddy D, Reddy YM, Atkins D, Rajasingh J, Kanmanthareddy A, Olyaee M, Dusing R, Pimentel R, Bommana S, Dawn B. Effect of atrial fibrillation ablation on gastric motility: the Atrial Fibrillation Gut Study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:531–536. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eberly LA, Garg L, Yang L, Markman TM, Nathan AS, Eneanya ND, Dixit S, Marchlinski FE, Groeneveld PW, Frankel DS. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in management of incident paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e210247. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piccini JP, Hammill BG, Sinner MF, Jensen PN, Hernandez AF, Heckbert SR, Benjamin EJ, Curtis LH. Incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation and associated mortality among Medicare beneficiaries, 1993-2007. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:85–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.962688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuck KH, Brugada J, Fürnkranz A, Metzner A, Ouyang F, Chun KJ, Elvan A, Arentz T, Bestehorn K, Pocock SJ, et al. Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2235–2245. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1602014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Squara F, Zhao A, Marijon E, Latcu DG, Providencia R, Di Giovanni G, Jauvert G, Jourda F, Chierchia G-B, De Asmundis C, et al. Comparison between radiofrequency with contact force-sensing and second-generation cryoballoon for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation catheter ablation: a multicentre European evaluation. Europace. 2015;17:718–724. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Providencia R, Defaye P, Lambiase PD, Pavin D, Cebron J-P, Halimi F, Anselme F, Srinivasan N, Albenque J-P, Boveda S. Results from a multicentre comparison of cryoballoon vs. radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: is cryoablation more reproducible? Europace. 2017;19:48–57. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt M, Dorwarth U, Straube F, Daccarett M, Rieber J, Wankerl M, Krieg J, Leber AW, Ebersberger U, Huber A, et al. Cryoballoon in AF ablation: impact of PV ovality on AF recurrence. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dukkipati SR, Cuoco F, Kutinsky I, Aryana A, Bahnson TD, Lakkireddy D, Woollett I, Issa ZF, Natale A, Reddy VY; HeartLight Study Investigators. Pulmonary vein isolation using the visually guided laser balloon: a prospective, multicenter, and randomized comparison to standard radiofrequency ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1350–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aryana A, Baker JH, Espinosa Ginic MA, Pujara DK, Bowers MR, O'Neill PG, Ellenbogen KA, Di Biase L, d'Avila A, Natale A. Posterior wall isolation using the cryoballoon in conjunction with pulmonary vein ablation is superior to pulmonary vein isolation alone in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: a multicenter experience. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boveda S, Metzner A, Nguyen D, Julian Chun KR, Goehl K, Noelker G, Deharo JC, Andrikopoulos G, Dahme T, Lellouche N, et al. Single-procedure outcomes and quality-of-life improvement 12 months post-cryoballoon ablation in persistent atrial fibrillation: results from the multicenter CRYO4PERSISTENT AF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;4:1440–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tondo C, Iacopino S, Pieragnoli P, Molon G, Verlato R, Curnis A, Landolina M, Allocca G, Arena G, Fassini G, et al. Pulmonary vein isolation cryoablation for persistent and long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation patients: clinical outcomes from real word multicentric observational project. Heart Rhythm. 2017;15:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knight BP, Novak PG, Sangrigoli R, Champagne J, Dubuc M, Adler SW, Svinarich JT, Essebag V, Hokanson R, Kueffer F, et al. ; STOP AF PAS Investigators. Long-term outcomes after ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation using the second-generation cryoballoon: final results from STOP AF post-approval study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;5:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.