Abstract

Excess mortality is often used to assess the health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. It involves comparing the number of deaths observed during the pandemic with the number of deaths that would counterfactually have been expected in the absence of the pandemic. However, published data on excess mortality often vary even for the same country. The reason for these discrepancies is that the estimation of excess mortality involves a number of subjective methodological choices. The aim of this paper was to summarize these subjective choices. In several publications, excess mortality was overestimated because population aging was not adjusted for. Another important reason for different estimates of excess mortality is the choice of different pre-pandemic reference periods that are used to estimate the expected number of deaths (e.g., only 2019 or 2015–2019). Other reasons for divergent results include different choices of index periods (e.g., 2020 or 2020–2021), different modeling to determine expected mortality rates (e.g., averaging mortality rates from previous years or using linear trends), the issue of accounting for irregular risk factors such as heat waves and seasonal influenza, and differences in the quality of the data used. We suggest that future studies present the results not only for a single set of analytic choices, but also for sets with different analytic choices, so that the dependence of the results on these choices becomes explicit.

Keywords: Research design, Statistical models, Risk factors, Data quality, Standardized mortality ratio

Abstract

Die Übersterblichkeit wird häufig verwendet, um die gesundheitlichen Auswirkungen der COVID-19-Pandemie zu beurteilen. Dazu gehört der Vergleich der Zahl von Todesfällen, die während der Pandemie festgestellt wurden, mit der Zahl von Todesfällen, die entgegen den Fakten ohne Pandemie zu erwarten gewesen wäre. Allerdings variieren die veröffentlichten Daten zur Übersterblichkeit oft, selbst für ein und dasselbe Land. Der Grund für diese Diskrepanzen liegt darin, dass die Schätzung der Übersterblichkeit ein Anzahl subjektiver methodischer Entscheidungen beinhaltet. Ziel der vorliegenden Arbeit war es, diese subjektive Auswahl zusammenzufassen. In verschiedenen Publikationen wurde Übersterblichkeit überschätzt, weil die Alterung der Bevölkerung nicht berücksichtigt worden war. Ein weiterer wichtiger Grund für unterschiedliche Schätzwerte der Übersterblichkeit besteht in der Auswahl verschiedener präpandemischer Referenzzeiträume, die für die Abschätzung der erwarteten Anzahl an Todesfällen verwendet wurden (z. B. nur 2019 oder 2015–2019). Andere Gründe für abweichende Ergebnisse umfassen eine unterschiedliche Auswahl von Indexperioden (z. B. 2020 oder 2020–2021), verschiedene Modellbildungen zur Bestimmung der erwarteten Sterblichkeitsraten (z. B. die Durchschnittsbildung der Sterblichkeitsraten vorangegangener Jahre oder die Verwendung linearer Trends), die Frage der Berücksichtigung unregelmäßiger Risikofaktoren wie Hitzewellen und saisonale Influenza sowie Unterschiede in der Qualität der verwendeten Daten. Die Autoren schlagen vor, dass zukünftige Studien ihre Ergebnisse nicht nur für einen einzelnen Satz von analytischen Entscheidungen darstellen, sondern auch für Sätze mit verschiedenen analytischen Entscheidungen, sodass die Abhängigkeit der Ergebnisse von diesen Entscheidungen deutlich wird.

Schlüsselwörter: Untersuchungsdesign, Statistische Modelle, Risikofaktoren, Datenqualität, Standardisierte Sterblichkeitsrate

The number of death cases caused by COVID-19 is not an appropriate indicator for assessing the consequences of the SARS-CoV‑2 pandemic and the effectiveness of measures taken to manage it. For one thing, the attribution of cause of death (death due to COVID-19, death with COVID-19, or unrelated death) and the quality of completed death certificates differ considerably between countries [1]. For another, the number of deaths caused by COVID-19 also depends on how frequently COVID-19 was tested for—testing capacity was often inadequate, especially during the early phase of the pandemic.

Excess mortality during the pandemic is an alternative for which the aforementioned definitional problems do not matter. However, it is not possible to distinguish between direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 when calculating excess mortality. Indirect effects include, for example, delayed cancer treatments or changes in healthcare utilization. In principle, one would need to find out what the mortality rate would have been in the pandemic period if the pandemic had not occurred. Since this is not possible from an epistemological point of view, calculation of excess mortality compares the number of deaths observed during the pandemic with the number of deaths that would have been expected based on mortality rates in pre-pandemic years.

Published excess mortalities often differ even for the same country. For example, the total number of excess deaths estimated for five northern European countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Iceland) for 2020 and 2021 varied between 14,738 and 37,708 in five different studies [2]. For 2020, both an under-mortality of 2% and an over-mortality of 6% were published for Germany [3, 4]. The reason for such discrepancies is that estimating excess mortality requires a number of subjective methodological choices. The aim of this paper is to raise awareness of these methodological issues.

The following example is presented to briefly illustrate how excess mortality is calculated in principle. Table 1 shows the individual steps for calculating the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for the population of the city of Frankfurt am Main in Germany. Table 2 contains the data necessary for the calculation, which include the number of deaths and the population for the years 2018–2020 separately for five age groups. Here, the number of persons in the population is equated with the number of person-years. First, the mortality rate per 1000 person-years is calculated for each age group in the two pre-pandemic years—for example, 3244 deaths in 32,655 person-years among people aged 80+ years in 2018 yields a mortality rate of 99.34 per 1000 person-years. Then, for each age group, the mean mortality rate is calculated from the 2018 and 2019 mortality rates. Finally, for each age group, we calculate how many deaths one would expect to occur in 2020 if the mortality rate in that year were exactly equal to the mean of the two pre-pandemic years. With 35,348 person-years among people aged 80+ years in 2020, one would expect 3385 deaths using the mean mortality rate of the two previous years of 95.763 per 1000 person-years. For the four other age groups, the number of expected deaths is calculated in an analogous manner. For all age groups combined, 6034.7 deaths would be expected to occur in 2020 if the age-specific mortality rates in 2020 had been the means in the two pre-pandemic years. Finally, the SMR is calculated as the ratio of the number of observed deaths and the number of expected deaths for 2020, i.e., SMR = 5982/6034.7 = 0.991. An SMR value greater than 1 indicates excess mortality, while an SMR value less than 1 indicates under-mortality. Thus, with an SMR of 0.991, there is minimal under-mortality. This simple calculation involves several choices that are responsible for the fact that published excess mortality figures often differ widely, even for the same country [5–7]. Six reasons for the wide range in reported excess mortalities are described below.

Table 1.

Calculation of the expected number of deaths for 2020 using the data of Table 2

| Age-specific mortality rates (per 1000 person-years) |

Age-specific mean mortality rate for 2018 and 2019 (per 1000 person-years) | Age-specific number of expected death cases for 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) |

2018 | 2019 | ||

| 0–29 | 0.218 | 0.280 | 0.25 | 62.4 |

| 30–59 | 1.799 | 1.573 | 1.69 | 590.7 |

| 60–69 | 10.232 | 10.483 | 10.36 | 738.5 |

| 70–79 | 24.259 | 24.701 | 24.48 | 1258.1 |

| ≥ 80 | 99.342 | 92.184 | 95.76 | 3385.0 |

| Sum | – | – | – | 6034.7 |

Table 2.

Age-specific deaths cases and age-specific population of the city of Frankfurt am Main for the years 2018–2020

| Death cases | Age-specific population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) |

2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| 0–29 | 54 | 70 | 57 | 247,193 | 249,939 | 250,364 |

| 30–59 | 618 | 547 | 549 | 343,513 | 347,668 | 350,303 |

| 60–69 | 709 | 735 | 726 | 69,294 | 70,110 | 71,303 |

| 70–79 | 1257 | 1275 | 1270 | 51,816 | 51,617 | 51,394 |

| ≥ 80 | 3244 | 3123 | 3380 | 32,655 | 33,878 | 35,348 |

| Sum | – | – | 5982 | – | – | – |

Lack of age standardization

As populations age, the number of deaths increases even if age-specific mortality rates remain the same. For example, in Germany, the number of people over 80 was 4.8 million in 2016 and 5.8 million in 2020 [3]. Without age standardization Germany would erroneously be found to have an SMR > 1, even if age-specific mortality rates remained constant. Levitt et al. stated that age standardization was not performed in three out of four published studies of excess mortality calculated for the whole world, and thus these three studies have a serious methodological flaw [6].

Choice of reference period

The number of expected deaths is calculated from mortality rates in the pre-pandemic years. However, there is a wide range of possible choices for the reference period. For example, in Germany, the number of deaths was 939,520 in 2019 and 954,874 in 2018. If 2019 is chosen as the reference year, the number of deaths expected in 2020 will be lower than if 2018 or 2018 and 2019 together are chosen as reference years. However, the choice of the reference period is quite arbitrary. Levitt et al. calculated excess mortality for 33 countries for 66 reference periods each [7]. The excess mortalities for one and the same country vary considerably depending on the selected reference period. For Germany, the minimum from the 66 excess mortalities is −4.4% and the maximum is 4.5% (United States: 14.3 and 18.7%, respectively; Sweden: −12.5 and 4.2%, respectively).

Choice of index period

The choice of the index period has a large impact on the estimated excess mortality. For example, the index period may be limited to a single wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, or it may include several years. Imagine that a multimorbid patient would have died in February 2021 without COVID-19 disease, but as a result of COVID-19 disease, the patient died as early as November 2020. If excess mortality is calculated for 2020 only, this death case will increase excess mortality. However, if 2020 and 2021 are chosen as the index period, this death does not increase excess mortality because the patient would have died during this 2‑year period with and without COVID-19 disease. A large proportion of deaths caused by COVID-19 involved vulnerable individuals with only a short life expectancy remaining. When a short index period of several months is chosen, such deaths increase excess mortality. However, this excess mortality decreases when the index period is extended. Levitt et al. calculated excess mortality for 33 countries, varying the length of the index period [7]. As expected, lengthening the index period resulted in a decrease in excess mortality.

Extrapolation of mortality rates

Once the reference period is established, there are several ways to calculate the mortality rate expected for the index period. In the example presented, the mean of the age-specific mortality rates from the reference period was used. Often, the years of the reference period show a trend in mortality rates over time. In most Western European countries, mortality rates decreased steadily from 2009 to 2019 [7]. Therefore, the expected mortality rate could alternatively be determined by extrapolating this trend. The extrapolation of a falling mortality rate leads to lower figures for the expected mortality rate and thus to a higher excess mortality rate [5]. However, extrapolating a trend in mortality for several years may result in generating an unrealistically low number of expected deaths. By using a spline function, which describes nonlinear curves by the piece-wise use of polynomials, the World Health Organization (WHO) had calculated numbers of expected deaths for Germany for 2020–2022 that were significantly lower than the number of deaths during 2015–2019. The high number of excess deaths calculated using this method was later revised downward by the WHO from 195,000 to 122,000 [8]. There is no standard for extrapolating mortality rates from reference years. An argument against extrapolating mortality trends is that they may not persist, as observed in the United States in recent pre-pandemic years [9].

Factoring out other irregularly occurring risk factors

Studies of excess mortality also differ in whether additional deaths from other irregularly occurring risk factors, such as heat waves and seasonal influenza, were factored out [6]. For example, heat-related deaths during the index period led to more observed deaths and thus higher excess mortality, whereas heat-related deaths during the reference period led to more expected deaths and thus lower excess mortality is calculated. There is currently no standard for whether or not to exclude heat-related or influenza-related deaths.

Data quality, number of age categories

Preliminary data on deaths provided by offices for national statistics are often updated after initial publication. Therefore, excess mortality results may differ when data provided at different times are used [5]. Furthermore, studies on excess mortality often differ in the choice of age categories. Kowall et al. gave an example to show that the SMR estimated for Germany in 2020 was higher when 5‑year age groups were used instead of 20-year age groups [5].

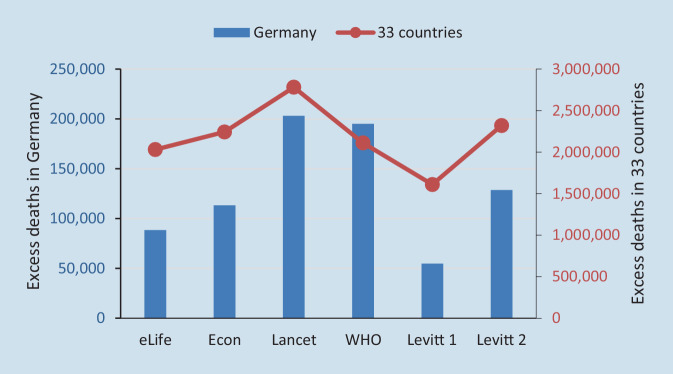

Figure 1 shows the combined excess deaths for 2020 and 2021 from four studies published in eLife, The Economist, The Lancet, and by the WHO, as well as from two further analyses by Levitt et al; Levitt 1 was age-adjusted, Levitt 2 was not age-adjusted [6]. For Germany, the estimated numbers of excess deaths ranged from 54,740 to 203,000, and for 33 selected (mainly OECD) countries combined, these numbers ranged from 1,609,862 to 2,780,726. The estimated number of excess deaths was lowest in the only age-standardized analyses—this was Levitt 1. The studies also differed in the choice of reference period, whether or not to exclude heat waves, and the modeling of the reference period [6]. These examples show how much methodological differences affect the estimated excess mortality.

Fig. 1.

Excess deaths estimates during 2020–2021 for Germany and for 33 selected countries The numbers shown in the figure are reported in [6]. These are results from four studies published in eLife, The Economist (Econ), The Lancet, and by the World Health Organization (WHO), as well as from two further analyses by Levitt et al.; Levitt 1 was age-adjusted, Levitt 2 was not age-adjusted

Conclusion

Excess mortality is important as an indicator of the health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and for evaluating the measures taken. Unlike cause-of-death statistics evaluations, the calculation of excess mortality using standardized mortality ratios does not depend on the attribution of causes of death and the quality of the death certificates. However, the wide range of methodological choices described here means that comparability of excess mortalities estimated for different regions or countries cannot be taken for granted. We suggest that future studies should not only present the result for a single set of analytical choices, but also for sets with different analytical choices, so that the dependence of the results on the choices becomes explicit.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

B. Kowall and A. Stang declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies mentioned were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

References

- 1.Beaney T, Clarke JM, Jain V, et al. Excess mortality: the gold standard in measuring the impact of COVID-19 worldwide? J R Soc Med. 2020;113:329–334. doi: 10.1177/0141076820956802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kepp KP, Björk J, Kontis V, et al. Estimates of excess mortality for the five Nordic countries during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020–2021. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51:722–1732. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyac204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kowall B, Standl F, Oesterling F, et al. Excess mortality due to COVID-19? A comparison of total mortality in 2020 with total mortality in 2016 to 2019 in Germany, Sweden and Spain. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0255540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morfeld P, Timmermann B, Lewis P, Erren T. Increased mortality in Germany and in the individual German states during the SARS-CoV-2-/COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;119:560–561. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0208.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowall B, Oesterling F, Pflaumer P, Jöckel KH, Stang A. Factors influencing results of mortality measurement in the corona pandemic: analyses of mortality in Germany in 2020. Gesundheitswesen. 2023;85:10–14. doi: 10.1055/a-1851-4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levitt M, Zonta F, Ioannidis JPA. Comparison of pandemic excess mortality in 2020–2021 across different calculations. Environ Res. 2022;213:113754. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levitt M, Zonta F, Ioannidis JPA. Excess death estimates from multiverse analyses in 2009–2021. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Methods for estimating the excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Msemburi W, Karlinsky A, Knutson V, et al. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature. 2022;613:130–137. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05522-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acciai F, Firebaugh G. Why did life expectancy decline in the United States in 2015? A gender-specific analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;190:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]