Abstract

The activities of two investigational fluoroquinolones and three fluoroquinolones that are currently marketed were determined for 182 clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. The collection included 57 pneumococcal isolates resistant to levofloxacin (MIC ≥ 8 μg/ml) recovered from patients in North America and Europe. All isolates were tested with clinafloxacin, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, and trovafloxacin by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards broth microdilution and disk diffusion susceptibility test methods. Gemifloxacin demonstrated the greatest activity on a per gram basis, followed by clinafloxacin, trovafloxacin, gatifloxacin, and levofloxacin. Scatterplots of the MICs and disk diffusion zone sizes revealed a well-defined separation of levofloxacin-resistant and -susceptible strains when the isolates were tested against clinafloxacin and gatifloxacin. DNA sequence analyses of the quinolone resistance-determining regions of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE from 21 of the levofloxacin-resistant strains identified eight different patterns of amino acid changes. Mutations among the four loci had the least effect on the MICs of gemifloxacin and clinafloxacin, while the MICs of gatifloxacin and trovafloxacin increased by up to six doubling dilutions. These data indicate that the newer fluoroquinolones have greater activities than levofloxacin against pneumococci with mutations in the DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV genes. Depending upon pharmacokinetics and safety, the greater potency of these agents could provide improved clinical efficacy against levofloxacin-resistant pneumococcal strains.

Resistance to penicillin, other beta-lactams, and several unrelated antimicrobial agent classes has been reported with increased frequency in recent years among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae (4, 5, 8, 11, 13, 19, 26, 28). Fluoroquinolone resistance has been described in pneumococcal clinical isolates and has been attributed primarily to mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) of the gyrase A and topoisomerase IV genes (3, 9, 15, 17, 27). Resistance to these agents has been slow to emerge (2, 6); however, a recent report from Canada has associated the increased use of fluoroquinolones over a several-year period for a variety of community-acquired infections with a parallel increase in fluoroquinolone resistance in pneumococcal isolates (7). Thus, the role of fluoroquinolones as first-line agents for community-acquired pneumonia, is under debate (6, 14, 18, 29; N. Fishman, B. Suh, L. M. Weigel, B. Lorber, S. Gelone, A. L. Truant, T. D. Gootz, J. D. Christie, and P. H. Edelstein, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 825, p. 111, 1999). In particular, a key area is whether the greater intrinsic activity of the newer fluoroquinolones against pneumococci will translate into useful activity against strains that are resistant to ofloxacin or levofloxacin.

This study has examined the in vitro activities of levofloxacin and four newer quinolones, i.e., clinafloxacin, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, and trovafloxacin, with potent activity against gram-positive bacteria. A collection of pneumococcal clinical isolates from North America and Europe that included 57 levofloxacin-resistant strains was examined using the NCCLS reference broth microdilution and disk diffusion susceptibility testing methods. Clinafloxacin and trovafloxacin had been examined in our previous study that included eight genetically characterized strains with high- and low-level quinolone resistance (17). They were included in the present study both for comparison with the two newer fluoroquinolones and because a number of off-scale MICs limited our assessment of the activity of clinafloxacin in the earlier study (17).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participating laboratories.

This collaborative study was conducted in the microbiology laboratories of three separate institutions, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and The University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHSC) at San Antonio. Each laboratory used a common protocol, some common supplies and reagents, and the same quality control strains.

Antimicrobial agents.

Reagent powder of each antimicrobial agent was kindly provided by its manufacturer. The agents (and their manufacturers) included clinafloxacin (Parke-Davis, Ann Arbor, Mich.), gatifloxacin (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Wollingford, Conn.), gemifloxacin (SmithKline Beecham, Philadelphia, Pa.), levofloxacin (Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Raritan, N.J.), and trovafloxacin (Pfizer, New York, N.Y.). A single lot of standard disks of each antibiotic manufactured by Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems (Cockeysville, Md.) was provided to each laboratory for the study.

Test isolates.

Each laboratory selected and tested approximately 50 to 60 unique pneumococcal clinical isolates from its own culture collection, to include approximately 15 levofloxacin-resistant strains. Most isolates were recovered from recent North American (CDC Active Bacterial Core Surveillance of the Emerging Infections Program Network) and European resistance surveillance studies.

Quality control organisms.

Each laboratory tested S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 (19) and two known levofloxacin-resistant strains, S. pneumoniae MN0418 and S. pneumoniae T62968 (17).

Broth microdilution susceptibility tests.

MICs of each antimicrobial agent were determined using the broth microdilution procedure described by the NCCLS (20). This included use of two different sources of cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 3% lysed horse blood as the test media. One lot of medium was prepared using Becton Dickinson Mueller-Hinton base, and the second lot was prepared using Difco base (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems). Microdilution panels were prepared at one site (UTHSC) and provided to each laboratory for the study. Test inocula were prepared from pneumococcal colonies grown on sheep blood agar plates that had been incubated for 20 to 24 h in 5% CO2. Colonies were suspended in 0.9% saline to obtain a suspension equivalent to the turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard and further diluted within 15 min to provide a final inoculum density of ca. 5 × 105 CFU/ml in the wells of the microdilution panels. Colony counts of positive control wells were performed to ensure the desired inoculum concentrations. Microdilution panels were incubated at 35°C in ambient air for 20 to 24 h prior to visual determination of MICs.

Disk diffusion tests.

Disk diffusion tests were also performed according to the methods recommended by the NCCLS (21), using 150-mm-diameter Mueller-Hinton plates containing 5% sheep blood. One laboratory used Becton Dickinson Mueller-Hinton agar, another laboratory used Remel (Lenexa, Kans.) commercially prepared plates, and plates were prepared in one of the laboratories using Difco (Detroit, Mich.) Mueller-Hinton agar. Plates were inoculated with an organism suspension equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard prepared in 0.9% saline as described above. Plates were incubated at 35°C in 5% CO2 for 20 to 24 h prior to measurement of inhibition zone diameters.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA.

Genetic analysis of 21 strains selected to represent both low-level and high-level levofloxacin resistance was conducted at the CDC. S. pneumoniae cells were grown to late exponential phase in 10 ml of Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco) supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (Difco) and harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–10 mM EDTA containing 0.5% deoxycholate and RNase (0.1 mg/ml) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Proteinase K and buffer AL (QIAamp tissue kit; QIAGEN, Chatsworth, Calif.) were added, and the mixture was incubated at 70°C for 30 min. Lysates were applied to QIAamp spin columns, and the genomic DNA was eluted according to the manufacturer's protocol.

PCR and DNA sequencing.

As described previously (17), oligonucleotide primers PNC6 and PNC7 or PNC10 and PNC11 were used to amplify a 232-bp or 329-bp gene fragment (excluding primers) of gyrA and parC, respectively (16), from chromosomal DNA of each of the 21 clinical isolates and the reference strain ATCC 49619. A 321-bp gene fragment of parE (excluding primers) was amplified with oligonucleotide primers SPPARE7 and SPPARE8 as described by Perichon et al. (25). Primers H4025 and H4026, described by Pan et al. (24), were used to amplify a 422-bp gene fragment of gyrB.

Amplification products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN). DNA sequencing was performed by ABI Prism dRhodamine terminator cycle sequencing (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and the ABI 377 automated sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems). DNA sequences were determined for both strands using products of independent PCRs. The DNASIS (Hitachi Software Engineering Co., Ltd., San Francisco, Calif.) genetic analysis programs were used for alignment of DNA sequences and deduced amino acid sequences.

RESULTS

The MICs of clinafloxacin, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, and trovafloxacin were determined for 182 clinical isolates of pneumococci. Fifty-seven had previously been determined to be resistant to levofloxacin (MIC ≥ 8 μg/ml). MICs of the fluoroquinolones did not differ significantly based on determinations performed in media prepared using the two different Mueller-Hinton broth bases. When the clinafloxacin, levofloxacin, and trovafloxacin MICs for 36 of the 57 fluoroquinolone-resistant strains that were also examined in a prior study (17) were compared, the MICs compared favorably (within a single doubling dilution) between the two studies (data not depicted). However, because the MICs determined in the prior study agreed slightly more closely with the values generated using the Becton Dickinson Mueller-Hinton broth in the present study, the MICs generated using that medium will be presented below.

The activities of the five agents in this study against both the levofloxacin-susceptible and -resistant isolates are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. Gemifloxacin demonstrated the greatest activity on a per gram basis, followed by clinafloxacin, trovafloxacin, gatifloxacin, and levofloxacin. MICs of gemifloxacin increased 4- to 8-fold with the high-level levofloxacin-resistant strains, as did clinafloxacin MICs, whereas gatifloxacin and trovafloxacin MICs generally rose from 32- to 64-fold against the highly levofloxacin-resistant isolates (Table 2). Table 2 also indicates the percentage of strains resistant to levofloxacin and trovafloxacin based upon interpretive breakpoints published by the NCCLS (22). Resistance to gatifloxacin was defined using breakpoints that have been recently approved by the NCCLS but not yet published (susceptible, ≤1 μg/ml; intermediate, 2 μg/ml; resistant, ≥4 μg/ml [M. J. Ferraro, personal communication]).

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities of 182 selected S. pneumoniae clinical isolates to five quinolones

| Quinolone | MICa (μg/ml) for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levofloxacin-susceptible isolates (n = 125)

|

Levofloxacin-resistant isolatesb (n = 57)

|

|||||

| 50% | 90% | Range | 50% | 90% | Range | |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 2 | 0.5–4c | 16 | >16 | 8 –>16 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25–2 | 8 | 8 | 2 –>8 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.06–0.5 | 4 | 8 | 0.25 –>8 |

| Clinafloxacin | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.06–0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25–4 |

| Gemifloxacin | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.015–0.12 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.06–2 |

50% and 90%, MICs at which 50 and 90% of the isolates are inhibited, respectively.

Levofloxacin resistance defined as MIC ≥ 8 μg/ml.

Two strains were intermediate (MIC = 4 μg/ml).

TABLE 2.

Comparative activities of fluoroquinolones against levofloxacin-susceptible and levofloxacin-resistant S. pneumoniae clinical isolates

| Susceptibility group and fluoroquinolone | No. of strains with MICs (μg/ml) of:

|

% Resistancea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | >16 | ||

| Levofloxacin susceptible (n = 125) | |||||||||||||

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 97 | 25 | 2 | |||||||||

| Gatifloxacin | 16 | 100 | 8 | 1 | |||||||||

| Trovafloxacin | 6 | 80 | 35 | 4 | |||||||||

| Clinafloxacin | 33 | 86 | 6 | ||||||||||

| Gemifloxacin | 7 | 84 | 29 | 5 | |||||||||

| Levofloxacin-resistant strains (n = 57) | |||||||||||||

| Levofloxacin | 11 | 35 | 11 | 100 | |||||||||

| Gatifloxacin | 2 | 9 | 43 | 3 | 96 | ||||||||

| Trovafloxacin | 1 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 18 | 17 | 3 | 67 | |||||

| Clinafloxacin | 1 | 32 | 22 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Gemifloxacin | 3 | 5 | 25 | 16 | 7 | 1 | |||||||

Based upon approved NCCLS interpretive breakpoints (21).

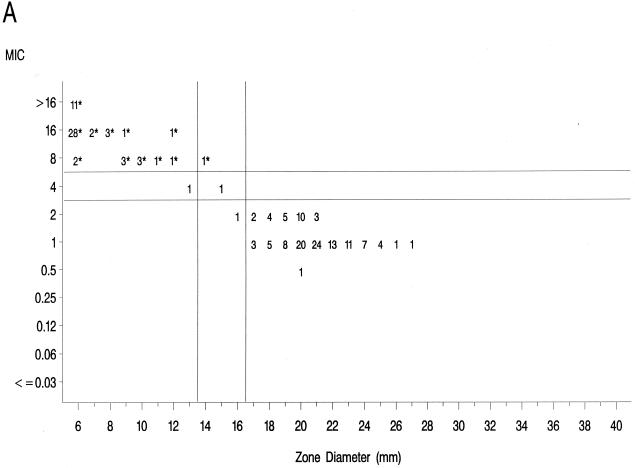

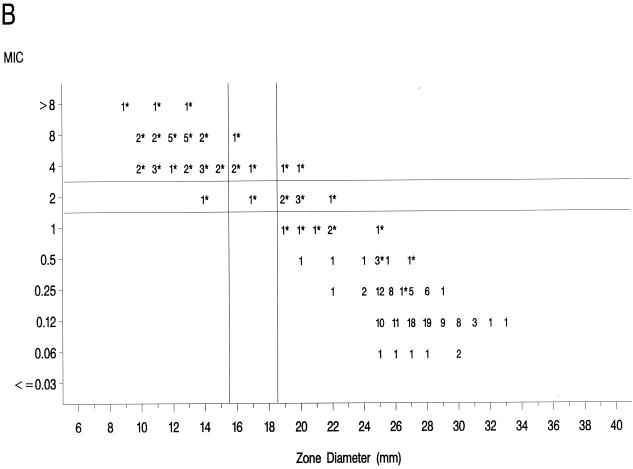

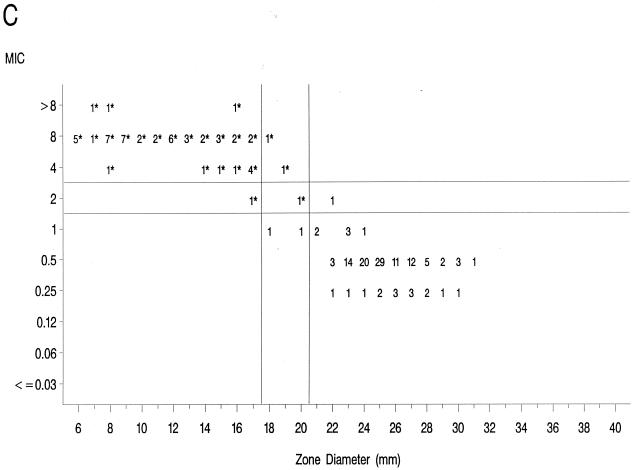

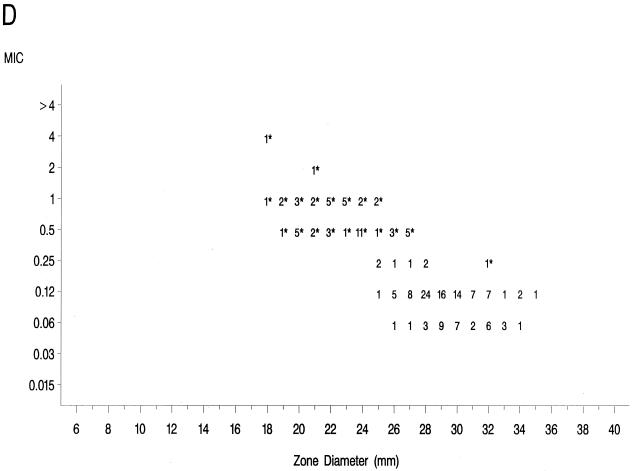

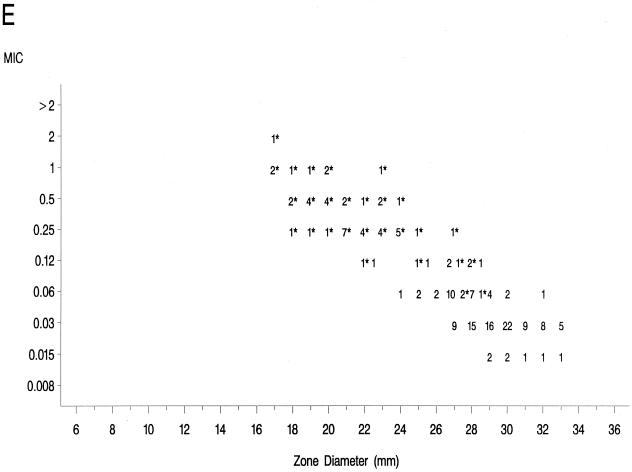

The source of Mueller-Hinton agar used to prepare the agar disk diffusion plates did not affect the fluoroquinolone zone diameters appreciably based upon testing of the control strains (data not shown) and when data from the 36 resistant isolates examined in the prior study (17) were compared to those obtained in the present study (data not further depicted). Scattergrams of MICs versus disk diffusion zone diameters (Fig. 1) revealed a well-defined separation of levofloxacin-resistant and -susceptible strains when tested against gatifloxacin and clinafloxacin. However, the distribution of levofloxacin-susceptible and -resistant strains overlapped when scattergrams were plotted for gemifloxacin and trovafloxacin (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Scatterplots of fluoroquinolone MICs (micrograms per milliliter) and zone diameters derived from testing 182 pneumococcal isolates. NCCLS-approved MIC and disk diffusion interpretive breakpoints for gatifloxacin, levofloxacin, and trovafloxacin ar indicated by the double horizontal and vertical lines on the graphs. Clinafloxacin and gemifloxacin do not yet have published NCCLS interpretive criteria. Levofloxacin-resistant strains are indicated by an asterisk. (A) Levofloxacin; (B) trovafloxacin; (C) gatifloxacin; (D) clinafloxacin; (E) gemifloxacin.

Twenty-one isolates were characterized by DNA sequence analysis for mutations in the QRDRs of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE. DNA sequences and inferred amino acid sequences of resistant isolates were compared with the corresponding sequences from the fluoroquinolone-susceptible NCCLS pneumococcal quality control strain, ATCC 49619. MIC profiles and the associated amino acid changes of the strains with defined mutations are listed in Table 3. A single parC mutation resulting in an amino acid change of Ser-79 to Phe or Tyr (three strains) resulted in a fourfold increase in the MICs of levofloxacin (intermediate resistance) and clinafloxacin. Although susceptibilities of these three strains to trovafloxacin, gatifloxacin, and gemifloxacin were reduced four- to eightfold, the MICs of trovafloxacin remained in the susceptible range (MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml), and those for gatifloxacin remained in the susceptible or intermediate categories (MICs, 1 to 2 μg/ml).

TABLE 3.

Amino acid changesa and associated fluoroquinolone susceptibility profiles for selected levofloxacin-resistant S. pneumoniae clinical isolates

| Strain | Amino acid change

|

MIC (μg/ml)b

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GyrA position:

|

ParC position:

|

ParE (position 435) | |||||||||

| 81 | 85 | 79 | 80 | 83 | LEVO | TROV | GATI | GEMI | CLFX | ||

| 49619 | Ser | Glu | Ser | Ser | Asp | Asp | 1 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| TN3659-6 | — | — | Phe | — | — | — | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| TN4201 | — | — | Phe | — | — | — | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| F30078 | — | — | Tyr | — | — | — | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| F30084 | Phe | — | — | — | — | Asn | 8 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.5 |

| F31324 | Phe | — | — | — | Asn | 8 | 0.5 | >8 | 0.12 | 0.5 | |

| TS173 | — | Gly | — | — | Asn | — | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| J3924 | Tyr | — | Tyr | — | — | — | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| CT00090 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| J3927 | Phe | — | Tyr | — | — | — | 16 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| CT01147 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| CT81035 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| MD70551 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| CT70490 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 4 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| TO3022 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 4 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 |

| CT5-5821 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| T703626 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| MD3904 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 1 |

| MD70023 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 0.5 |

| MD70626 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| MN00418 | Phe | — | Phe | — | — | — | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| J3810 | Phe | — | — | Pro | Tyr | — | >16 | 4 | 8 | 0.5 | 1 |

All amino acid positions are based on the corresponding S. pneumoniae gene sequences; —, no change.

Abbreviations: LEVO, levofloxacin; TROV, trovafloxacin; GATI, gatifloxacin; GEMI, gemifloxacin; CLFX, clinafloxacin.

Double mutations involving the codons for Ser-79 of ParC and Ser-81 of GyrA were detected in 14 of the 21 strains analyzed (Table 3). Increased MICs associated with these mutations were as follows: clinafloxacin and gemifloxacin, 8- to 32-fold; levofloxacin and gatifloxacin, 16- to 32-fold; and trovafloxacin, 32- to 64-fold. MICs of gatifloxacin, levofloxacin, and trovafloxacin for these strains were at or above the resistance breakpoint defined by the NCCLS for these compounds.

Less typical combinations of mutations were found in 4 of the 21 genetically characterized strains. Double or triple mutations involving amino acid positions other than Ser-79 of ParC and Ser-81 of GyrA were associated with MICs that were either lower (three strains) or higher (one strain) than the typical GyrA plus ParC mutants (Table 3). These four strains are the subject of further ongoing genetic studies.

DISCUSSION

This multicenter study has assessed the in vitro activities of four newer fluoroquinolones against a collection of pneumococcal isolates, including 57 strains resistant to levofloxacin that were recovered during recent active surveillance studies in North America, Belgium, and France. While a U.S. surveillance study conducted in 1996 and 1997 reported that only 0.2% of strains were resistant to ofloxacin (28), a recent Canadian study found 2.9% of isolates recovered from adult patients from 1997 to 1998 were fluoroquinolone nonsusceptible (7), and a study from Hong Kong has reported that 5.5% of multidrug-resistant strains were nonsusceptible to levofloxacin (15). More recently, the horizontal transfer of ParC and GyrA genes with mutations resulting in high-level quinolone resistance in pneumococci through recombination has been demonstrated (9). Thus, it is possible that the increased use of these broad-spectrum agents for treatment of community-acquired respiratory infections may lead to increased resistance in pneumococci either through mutations of the target sites of the fluoroquinolones or through transformation with genes derived from other organisms, e.g., the genetically related viridans group streptococci.

Although the four newer quinolones included in the present study showed improved activities against the levofloxacin-resistant isolates, high-level levofloxacin resistance isolates (MIC ≥ 16 μg/ml) with mutations in both gyrA and parC also had the most highly elevated MICs of the four newer compounds. Intermediate or low-level resistance to levofloxacin (seven strains [MICs of 4 to 8 μg/ml]) was associated with a modest increase (4- to 8-fold) of the MICs of clinafloxacin, gemifloxacin, and trovafloxacin and with an 8- to 16-fold increase in the MIC of gatifloxacin. The MICs associated with a single amino acid alteration of ParC (Ser-79), or a double mutation involving GyrA (Ser-81) and ParE (Asp-435), were consistent with previous investigations of the effects of target site modifications on the activities of various fluoroquinolones (7, 12, 16, 17, 23–25, 27). However, genetic analyses revealed eight different patterns of amino acid changes among the 21 strains, suggesting that in clinical isolates of pneumococci the site of the initial mutational event in the evolution of fluoroquinolone resistance may be less restricted than has been previously proposed based on data from in vitro-selected mutants. In addition, our data do not allow an assessment of the potential role of efflux-mediated resistance among these strains (10).

The greater intrinsic potency of the newer fluoroquinolones for pneumococci has been confirmed in this study. However, strains that were resistant to levofloxacin also demonstrated diminished susceptibility or frank resistance to the newer quinolones examined against these collections of strains as noted above. The well-defined separations of levofloxacin-resistant from -susceptible strains on scatterplots of MICs versus disk diffusion zone diameters for gatifloxacin and clinafloxacin suggest that it should be possible to develop breakpoints that will distinguish susceptible from resistant populations for these agents. The overlap of levofloxacin-resistant and -susceptible strains on the scatterplot for gemifloxacin suggests that the selection of interpretive breakpoints for that agent may be difficult.

In summary, this study has demonstrated that pneumococcal clinical isolates with mutations in the QRDR of both gyrA and parC are associated with markedly increased MICs of levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, and trovafloxacin. The MICs of clinafloxacin and gemifloxacin were affected to a lesser degree by the presence of these mutations in the genes encoding these subunits of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. The increases in MICs observed with these agents resulted in concomitant reductions in the zone diameters when tested by the standard NCCLS disk diffusion method. However, determinations of appropriate zone diameter breakpoints for clinafloxacin and gemifloxacin must await approval and publication of their respective MIC interpretive criteria by the NCCLS. Unfortunately, the development of clinafloxacin for clinical use has recently been suspended, and the use of trovafloxacin has been highly restricted due to toxicity concerns. Animal model and human clinical studies will be required to ascertain whether the greater potency of gemifloxacin against the pneumococcal strains that harbor mutations affecting both gyrA and parC could result in therapeutic efficacy. It will be critical to monitor the susceptibility of contemporary pneumococci to the fluoroquinolones as the use of these agents for therapy of common respiratory infections becomes increasingly popular.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by Bristol-Myers Squibb and SmithKline Beecham pharmaceutical companies.

The quinolone-resistant strains tested by MGH were graciously provided by the Centre National de Reference des Pneumocoques, Créteil, France, and André Bryskier, of Hoechst Marion Roussel, Inc., Romainville, France. We thank Jean Spargo (MGH), Leticia McElmeel (UTHSC), and Sharon Crawford (UTHSC) for their excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balas D, Fernandez-Moreira E, DeLaCampa A G. Molecular characterization of the gene encoding the DNA gyrase A subunit of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2854–2861. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2854-2861.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartlett J G, Breiman R F, Mandell L A, File T M., Jr Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: guidelines for management. Guideline from The Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:811–838. doi: 10.1086/513953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard L, Nguyen Van J-C, Mainardi J-L. In vivo selection of Streptococcus pneumoniae resistant to quinolones, including sparfloxacin. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1995;1:60–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1995.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breiman R F, Butler J C, Tenover F C, Elliott J, Facklam R R. Emergence of drug-resistant pneumococcal infections in the United States. JAMA. 1994;271:1831–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler J C, Hofmann J, Cetron M S, Elliott J A, Facklam R R, Breiman R F the Pneumococcal Sentinel Surveillance Working Group. The continued emergence of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States: an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's pneumococcal sentinel surveillance system. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:986–993. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell G D., Jr Commentary on the 1993 American Thoracic Society guidelines for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 1999;115(Suppl. 3):14S–18S. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.suppl_1.14s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen D K, McGeer A, de Azavedo J C, Low D E. Decreased susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to fluoroquinolones in Canada. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:233–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doern G V, Brueggemann A B, Huynh H, Wingert E, Rhomberg P. Antimicrobial resistance with Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States, 1997–98. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:757–765. doi: 10.3201/eid0506.990603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrandiz M J, Fenoll A, Linares J, De La Campa A D. Horizontal transfer of parC and gyrA in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:840–847. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.4.840-847.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill M J, Brenwald N P, Wise R. Identification of an efflux pump gene, pmrA, associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:187–189. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein F W, Acar J F the Alexander Project Collaborative Group. Antimicrobial resistance among lower respiratory tract isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae; results of a 1992–1993 Western Europe and USA collaborative surveillance study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38(Suppl. A):71–84. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.suppl_a.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gootz T D, Zaniewski R, Haskell S, Schmieder B, Tankovic J, Girard D, Courvalin P, Polzer R J. Activity of the new fluoroquinolone trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) against DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae selected in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2691–2697. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruneberg R N, Felmingham D. Results of the Alexander Project: a continuing, multicenter study of the antimicrobial susceptibility of community-acquired lower respiratory tract bacterial pathogens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;25:169–181. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(96)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heffelfinger J D, Dowell S F, Jorgensen J H, et al. Management of community-acquired pneumonia in the era of pneumococcal resistance: a report from the Drug-Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Therapeutic Working Group. Arch Intern Med, 2000;160:1399–1408. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho P-L, Que T-L, Tsang D N-C, Ng T-K, Chow K-H, Seto W-H. Emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance among multiply resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Hong Kong. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1310–1313. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janoir C, Zeller V, Kitzis M-D, Moreau N J, Gutmann L. High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae requires mutations in parC and gyrA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2760–2764. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorgensen J H, Weigel L M, Ferraro M J, Swenson J M, Tenover F C. Activities of newer fluoroquinolones against Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates including those with mutations in the gyrA, parC, and parE loci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:329–334. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legg J M, Bint A J. Will pneumococci put quinolones in their place? J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44:425–427. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDougal L K, Rasheed J K, Biddle J W, Tenover F C. Identification of multiple clones of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2282–2288. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A5. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Approved standard M2-A7. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Tenth informational supplement, M100-S10. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan X-S, Ambler J, Mehtar S, Fisher L M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–2326. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Cloning and characterization of the parC and parE genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae encoding DNA topoisomerase IV: role in fluoroquinolone resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4060–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4060-4069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perichon B, Tankovic J, Courvalin P. Characterization of a mutation in the parE gene that confers fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1166–1167. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simor A E, Louie M, Low D E The Canadian Surveillance Network. Canadian national survey of prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2190–2193. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tankovic J, Perichon B, Duval J, Courvalin P. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2505–2510. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thornsberry C, Ogilvie P, Kahn J, Mauriz Y. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis in the United States in 1996–1997 respiratory season. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;29:249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker R C. The fluoroquinolones. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:1030–1037. doi: 10.4065/74.10.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]