Abstract

Objectives

The stability of the analytes most commonly used in routine clinical practice has been the subject of intensive research, with varying and even conflicting results. Such is the case of alanine aminotransferase (ALT). The purpose of this study was to determine the stability of serum ALT according to different variables.

Methods

A multicentric study was conducted in eight laboratories using serum samples with known initial catalytic concentrations of ALT within four different ranges, namely: <50 U/L (<0.83 μkat/L), 50–200 U/L (0.83–3.33 μkat/L), 200–400 U/L (3.33–6.67 μkat/L) and >400 U/L (>6.67 μkat/L). Samples were stored for seven days at two different temperatures using four experimental models and four laboratory analytical platforms. The respective stability equations were calculated by linear regression. A multivariate model was used to assess the influence of different variables.

Results

Catalytic concentrations of ALT decreased gradually over time. Temperature (−4%/day at room temperature vs. −1%/day under refrigeration) and the analytical platform had a significant impact, with Architect (Abbott) showing the greatest instability. Initial catalytic concentrations of ALT only had a slight impact on stability, whereas the experimental model had no impact at all.

Conclusions

The constant decrease in serum ALT is reduced when refrigerated. Scarcely studied variables were found to have a significant impact on ALT stability. This observation, added to a considerable inter-individual variability, makes larger studies necessary for the definition of stability equations.

Keywords: alanine aminotransferase (ALT), enzyme, preanalytical phase, stability, storage

Introduction

For laboratory tests to be of clinical usefulness, the composition of the samples tested in vitro should reflect their real composition in vivo. To such purpose, constituent concentrations must remain stable during the preanalytical period. The stability of biochemical analytes is defined as the ability of a sample to retain the initial value of its constituents within specified limits over a period of time under specified storage conditions [1, 2]. The stability of the biological magnitudes most frequently measured in serum and plasma under specific conditions in clinical laboratories has been analyzed in numerous studies, with varying and often conflicting results. The inconsistency of results may arise from the lack of standardized experimental protocols, guidelines or validated recommendations about analyte stability testing, and the absence of standard maximum permissible instability specifications [3–5]. In 2006, the Spanish Society of Laboratory Medicine (SEQCML) discussed this problem and developed a stability testing protocol. In 2019, a new version of the protocol was published to include a preliminary study and a complete stability test to define a stability equation [1].

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT, EC.2.6.1.2) is an enzyme whose stability in the short term (seven days) has been intensively studied, with inconsistent results, which hinders the development of a consensus stability equation [3]. Some studies show significant instability of ALT in whole blood [6–8] or in serum stored at 4 °C [9–11]. Other studies reveal increased catalytic concentrations both in whole blood and serum/plasma [12, 13]. In contrast, most authors report a decrease of catalytic concentrations at room temperature (22–25 °C) [9, 14], under refrigeration [15], and at −20 °C [9, 14, 16].

In light of the inconsistency of results, a multicentric study was conducted in eight hospitals to assess the stability of ALT using four experimental models and four analytical platforms. As variables with a potential effect on stability, we included time, temperature and the initial catalytic concentration of the enzyme.

Materials and methods

A multicentric study was performed in eight hospitals in Spain. Serum samples with known initial catalytic concentrations of ALT were stored for seven days at two temperatures (room temperature and refrigerated) and analyzed using four experimental models:

Model 1: approximately 20 serum samples were selected (five samples with ALT > 400 U/L (>6.67 μkat/L), five samples with 200 < ALT < 400 U/L (3.33 < ALT < 6.67 μkat/L), five samples with 50 < ALT < 200 U/L (0.83 < ALT < 3.33 μkat/L), and five samples with ALT < 50 U/L (<0.83 μkat/L). Samples were divided into ten aliquots that were transferred to Eppendorf tubes. Five aliquots of each sample were stored at room temperature, whereas the other five were stored refrigerated. Tubes were capped and protected from light without shaking. An aliquot of each sample was frozen at −70 °C at intervals of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 7 days.

On day 8, all aliquots were thawed and analyzed in the same run. To minimize contamination, the samples with the lowest catalytic concentrations of ALT were first analyzed.

Model 2: approximately 40 serum samples were selected: ten samples with ALT > 400 U/L (>6.67 μkat/L), ten samples with 200 < ALT < 400 U/L (3.33 < ALT < 6.67 μkat/L), ten samples with 50 < ALT < 200 U/L (0.83 < ALT < 3.33 μkat/L), and ten samples with ALT < 50 U/L (<0.83 μkat/L). After the first analysis, primary tubes were sealed immediately. Half of the aliquots were stored refrigerated and the other half were stored at room temperature protected from light without shaking. Aliquots were transferred into the tubes and analyzed at intervals of 0 (repeat initial value), 1, 2, 3, and 7 days. In each case, the remainder of the sample was stored in the tube and immediately sealed.

To minimize contamination, the samples with the lowest catalytic concentrations of ALT were first analyzed.

Model 3: approximately 200 serum samples were selected: 50 samples with ALT > 400 U/L (>6.67 μkat/L), 50 samples with 200 < ALT < 400 U/L (3.33 < ALT < 6.67 μkat/L), 50 samples with 50 < ALT < 200 U/L (0.83 < ALT<3.33 μkat/L), and 50 samples with ALT < 50 U/L (<0.83 μkat/L). Immediately after the first result was obtained, half of the primary tubes were stored refrigerated, whereas the other half were stored at room temperature. All tubes were sealed and stored protected from light without shaking.

From the day of collection, each day 14 tubes stored at room temperature and another 14 refrigerated were reanalyzed in the laboratory at normal working hours.

Model 4: approximately 20 serum samples were selected: five samples with ALT > 400 U/L (>6.67 μkat/L), five samples with 200 < ALT < 400 U/L (3.33 < ALT < 6.67 μkat/L), five samples with 50 < ALT < 200 U/L (0.83 < ALT < 3.33 μkat/L), and five samples with ALT < 50 U/L (<0.83 μkat/L). Within the first 2 h after centrifugation, four pools were prepared (one pool for each ALT catalytic concentration range). Each pool was divided into ten aliquots, which were transferred into Eppendorf tubes. Five aliquots were stored at room temperature, whereas the other five were stored refrigerated. All tubes were sealed and stored protected from light without shaking. An aliquot of each sample was frozen at −70 °C at intervals of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 7 days.

On day 8, all aliquots were thawed simultaneously for analysis in quintuplicate in the same run.

Each model was tested in different laboratories using different analytical platforms (Table 1). The incubation temperature at room temperature was set at 20–24 and 4–8 °C for refrigeration.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the analytical platforms used in the different experimental models.

| Experimental Model | Analytical platform | Method (ALT assay) | Number of samples tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AU (Beckman Coulter) | NADH with PyP | 156 |

| Architect c16000 (Abbott) | NADH without PyP | 160 | |

| Advia 2400 (Siemens) | NADH without PyP | 160 | |

| 2 | AU (Beckman Coulter) | NADH with PyP | 160 |

| Advia 2400 (Siemens) | NADH without PyP | 96 | |

| Cobas c702 (Roche) | NADH without PyP | 194 | |

| 3 | Advia 2400 (Siemens) | NADH without PyP | 242 |

| 4 | Cobas c702 (Roche) | NADH without PyP | 80 |

| Architect c16000 (Abbott) | NADH without PyP | 160 |

PyP, pyridoxal-5′-phosphate; NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide.

Tubes were capped or sealed and stored protected from light without shaking to avoid the effects of other factors of influence. The quality of results was assured by the use of laboratory internal quality control measures. Hemolyzed or lipemic samples were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Percent deviation (PD) from the initial value was used as the basic statistic (initial catalytic concentration − final catalytic concentration)/initial catalytic concentration × 100). Following SEQCML guidelines, we determined the stability equation showing the relationship between PD variations over time by linear regression using the least squares method [1]. The model was forced to include the coordinate origin, as at time 0 loss of stability must be 0. A confidence interval of 95% was calculated for the slope. Visual inspection of results suggested a first-order linear fit, which is easier to interpret. Therefore, all models followed:

(β = daily percent deviation from initial ALT catalytic concentration).

The level of significance for comparison tests (p) and the goodness-of-fit (Pearson's r) of each stability equation are provided.

A stepwise multiple linear regression was performed to test the individual effect of each variable (temperature, initial ALT catalytic concentration, experimental model and analytical platform). An α error of 0.05 was set for inclusion of variables.

In the case of analytical platform or initial catalytic concentration, univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess PD of results on day 7. The individual difference between categories was determined using the least significant difference test (LSD).

Informed consent from patients was not required as waste samples were used in this study. All data were previously anonymized.

Results

Table 1 shows the analytical features of each experimental model and the number of samples tested.

In general terms, temperature demonstrates to exert clear effects on the stability of ALT in serum, with a decrease of 4.77%/day at room temperature, as compared to a decrease of 0.94%/day under refrigeration. Table 2 describes the stability equations obtained by each of the participating laboratories for samples stored at room temperature and refrigerated.

Table 2:

Variations in catalytic concentrations of ALT over time. Stability equations.

| Model | Platform | Refrigerated (n = 704) | At room temperature (n = 704) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | r | β | 95%CI β | p-Value | r | β | IC 95% β | ||

| 1 | Advia | 0.001 | 0.661 | −0.902 | between −1.393 and −0.410 | <0.001 | 0.947 | −3.87 | between −4.504 and −3.248 |

| 1 | Architect | <0.001 | 0.500 | −1.117 | between −1.550 and −0.683 | <0.001 | 0.903 | −8.742 | between −9.673 and −7.811 |

| 1 | AU | <0.001 | 0.677 | .0.695 | between −0.865 and −0.525 | 0.001 | 0.679 | −3.384 | between −5.017 and −1.590 |

| 2 | AU | <0.001 | 0.752 | −1.251 | between −1.496 and −1.005 | <0.001 | 0.942 | −5.199 | between −5.613 and −4.785 |

| 2 | Cobas | <0.001 | 0.870 | −1.607 | between −1.796 and −1.417 | <0.001 | 0.908 | −5.824 | between −6.353 and −5.294 |

| 2 | Advia | <0.001 | 0.626 | −1.321 | between −1.783 and −0.858 | <0.001 | 0.829 | −5.048 | between −6.096 and −4.000 |

| 3 | Advia | <0.001 | 0.345 | −0.605 | between −0.902 and −0.307 | <0.001 | 0.822 | −2.189 | between −2.463 and −1.915 |

| 4 | Cobas | 0.506 | 0.107 | 0.110 | between −0.222 and 0.442 | <0.001 | 0.939 | −2.001 | between −2.250 and −1.752 |

| 4 | Architect | 0.001 | 0.720 | −1.025 | between −1.569 and −0.481 | <0.001 | 0.855 | −5.609 | between −7.484 and −3.733 |

| Total | <0.001 | 0.564 | −0.941 | between −1.051 and −0.831 | <0.001 | 0.832 | −4.772 | between −5.025 and −4.518 | |

p, level of significance; r, goodness of fit (Pearon's r); β, daily percent deviation from ALT catalytic concentration.

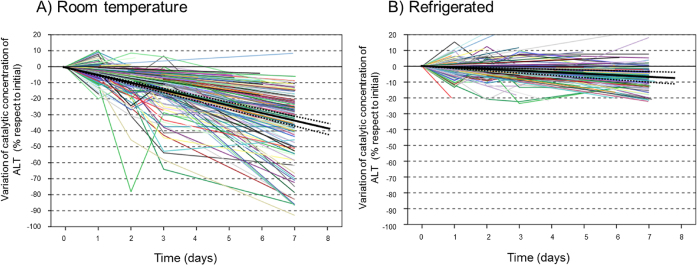

Inter-individual variability in loss of stability is significantly higher in the samples stored at room temperature (Figure 1). The graphs suggest a general model of linear reduction of catalytic concentrations over time for all experimental models and analytical platforms. The improvement of the R2 coefficient with quadratic or cubic fitting was not significant either at room temperature (0.545 for linear fitting vs. 0.547 for quadratic and 0.558 for cubic) or refrigerated (0.165 vs. 0.166 and 0.189).

Figure 1:

Effect of temperature and experimental model. Individual data and linear regression (black solid line) with a 95% CI for the slope (dotted lines).

(A) Tests at room temperature. (B) Test under refrigeration.

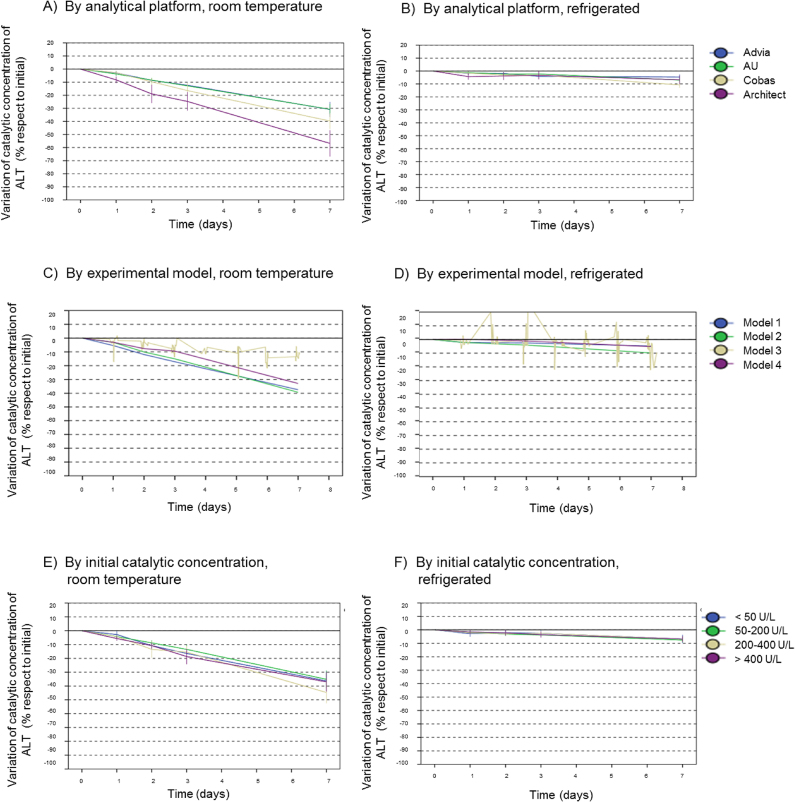

Figure 2 displays variations in ALT catalytic concentrations over time based on the experimental model (2A), the initial ALT catalytic concentration (2B), and the analytical platform (2C).

Figure 2:

Variations in catalytic concentrations of ALT over time as a function of the different variables.

(A, B) Analytical platform, (C, D) experimental model, (E, F) initial catalytica concentration. Represented as line plot adding the means for each time point with the 95% confidence interval for the mean.

Stepwise multiple linear regression analysis was performed including the five variables (by order: time, temperature, analytical platform, experimental model and, initial catalytic concentration). An increase of 0.05 in the probability of F was considered significant. All variables showed a significant effect on variations in the catalytic concentrations of ALT, except for experimental model. The explanatory power of the model increased from R2 = 0.448 when time was included as the only predictor, to R2 = 0.483 when temperature was included, to R2 = 0.594 when the method was included, and R2 = 0.602 when initial catalytic concentration was incorporated, being the latter the variable with the lowest weight.

Differences between mean PD values at day 7 for the four analytical platforms were assessed by an ANOVA test including all results (both for samples stored at room temperature and refrigerated). A significant difference was found between platforms (ANOVA p < 0.01) with a more substantial loss of stability in Architect-Abbott (−31.8%), followed by Cobas-Roche (−26.3%), AU-Beckman (−18.4%), and Advia-Siemens (−14.5%). The LSD test revealed significant differences between Abbott or Cobas and AU or Advia. Differences were also observed between study models (ANOVA p < 0.01), primarily between model 3 (−8.8%) and the other models (−20.7% for model 1, −24.8% for model 2, and −19% for model 4).

The influence of initial catalytic concentration detected by multiple regression was not seen in day 7 results (ANOVA p = 0.430), which corresponds to the small difference seen in the graph.

Discussion

This multicentric study was performed to assess the influence of different variables on variations in the catalytic concentrations of ALT over time. All experimental designs showed a reduction of catalytic concentrations over time, which is consistent with the results of some previous studies [3, 17, 18], although our results also contrast with other authors who did not find any variation [19–21] or report an increase in catalytic concentrations of this enzyme [22].

According to our results, temperature proved to be a significant factor of influence on stability, with stability being five-fold higher in samples stored refrigerated, as compared to storage at room temperature. The greatest loss of stability occurs at room temperature, which is in line with the literature [22, 23].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the influence of variables that had not been considered in previous studies on ALT stability. These variables include initial catalytic concentration, analytical platform and the experimental model [7, 9, 11].

Catalytic concentrations (especially high concentrations) have not been considered in previous studies on ALT stability. A limitation of previous studies is that they were based on low catalytic concentrations or on concentrations within the reference range [8, 10, 13, 14, 16]. Hence, in many studies, analytical variability could have masked variations caused by the loss of stability. In our study, we considered catalytic concentration groups over the analytical range, which is of greater clinical usefulness, from <50 U/L (0.83 μkat/L) to >400 U/L (3.33 μkat/L). Multivariate analysis shows a weak influence of initial catalytic concentration, with samples with high values showing the greatest instability. Notably, this effect does not seem to be maintained until day 7, which suggests that this effect could stem from a greater imprecision of ALT quantification methods in samples with a low catalytic concentration.

Four analytical platforms were included in multivariate analysis. Loss of stability was more relevant when Architect or Cobas were used, as compared to Advia or AU. The greatest instability was observed in Architect. This phenomenon may be explained by the differential composition of the reagents used by the analyzers and the addition of pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PyP) as a coenzyme, which is necessary to improve the stability of the method. The methods where PyP is not added depend on the presence of endogenous PyP in the sample. PyP degradation with exposure to light is widely known, as is the need to refrigerate samples. Further studies are warranted to investigate the potential relationship between PyP and catalytic concentrations of ALT.

In our study, stability was assessed in different experimental models. In their recent guidelines for analyte stability testing, SEQCML recommended the use of an equation or profile instead of a single stability cut-off value [1]. Based on a stability equation, laboratories can set their cut-off points according to the established specifications.

For results to be reliable, the use of an appropriate experimental model is of great relevance. In our study, the models proposed have advantages and disadvantages in terms of viability of the model and interpretation of results. For example, models 1 and 4 are based on the assumption that no loss of stability occurs when the sample is stored at −70 °C. Therefore, model 2 is recommended for samples that cannot be frozen or when catalytic concentrations become unstable with freezing. Nevertheless, control materials from the same batch should have been used to assess potential biases.

Model 1 is very similar to that described in a recently published stability testing protocol [1]. However, a limitation of models 1, 2, and 3 is that determinations were performed once and outliers may have not been detected. Analysis in quintuplicate of model 4 enables to discard outliers and reduces the imprecision of results. The main limitation of this model is the small number of samples used (four pools). In spite of multiple differences among the four experimental models, the multiple regression model only showed differences in day-7 results. A potential confounding factor is the fact that model 3 is the only model were determinations were not performed at specific time points, and this model was only tested in a laboratory due to its technical complexity. The platform used to test model 3 (Advia Siemens), together with AU Beckham was the one with the lowest loss of stability, which may explain differences with other models.

The main limitations of this study are the small number of analytical platforms tested and the low number of repetitions in some of them. Moreover, the number of samples included in some of the experimental models was low, which hinders drawing robust conclusions. Investigating the influence of other factors found in routine laboratory practice such as exposure to air or light on ALT or PyP concentrations is a worthwhile avenue for future research.

Individual results grouped by factor of influence revealed significant inter-individual variability in terms of ALT stability. This finding demonstrates the limitations of and difficulty in establishing a fixed and single stability cut-off value for a biochemical magnitude for the general population under specific conditions. Thus, the samples of some patients lose stability more rapidly (those with a sharper slope in Figure 1) and their results would be considered to be “within the stability period”, when their sample actually is no longer stable. The opposite occurs in individuals with very stable catalytic concentrations of ALT over time, whose samples can be stored for longer. This effect could be partially explained by the presence of thermosensitive isoenzymes, as documented in lactate dehydrogenase [23].

It could be hypothesized that the same phenomenon occurs in other analytes of clinical interest. Thus, stability cannot be determined at a single time point or using a single equation. However, this is the best tool currently available in clinical laboratories to test stability.

This study brings out the necessity of assessing the influence of a variety of factors in the stability of biochemical magnitudes, some of which with a weak effect in the case of ALT (initial catalytic concentrations or experimental model), whereas other factors may have a significant impact (storage temperature or analytical platform). Graphical representations showing the stability of all samples allow a visual inspection of inter-individual variability in the loss of stability. Defining a stability line can be useful for each laboratory to set their stability limits according to their specifications.

Footnotes

Research funding: None declared.

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Article Note: The original submission can be found here: https://doi.org/10.1515/almed-2019-0029

References

- 1.Gómez-Rioja R, Amaro MS, Diaz-Garzón J, Bauçà JM, Espartosa DM, Fernández-Calle P. A protocol for testing the stability of biochemical analytes. Technical document. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019;57(12):1829–36. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2019-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guder WG, Fiedler M, da Fonseca Wollheim F, Schmitt Y, Töpfer G, Wisser H, et al. The quality of diagnostic samples. 4th Complet Revised Oxford BD Diagnostics; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rioja RG, Espartosa DM, Segovia M, Ibarz M, Llopis MA, Bauça JM, et al. Laboratory sample stability. Is it possible to define a consensus stability function? An example of five blood magnitudes. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2018;56:1806–18. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2017-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastin P, Favresse J, Streel C, Maisin D, Fillée C, Gruson D. Assessment of in vitro stability: a call for harmonization across studies. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2018;56:e121–4. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2017-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sureda-Vives M, Morell-Garcia D, Rubio-Alaejos A, Valiña L, Robles J, Bauça JM. Stability of serum, plasma and urine osmolality in different storage conditions: relevance of temperature and centrifugation. Clin Biochem. 2017;50:772–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laessig RH, Indriksons AA, Hassemer DJ, Paskey TA, Schwartz TH. Changes in serum chemical values as a result of prolonged contact with the clot. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;66:598–604. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/66.3.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu SY, MacLeod J. Effect of three-day clot contact on results of common biochemical tests with serum. Clin Chem. 1986;32:2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heins M, Heip W, Withold W. Storage of serum or whole blood samples? Effects of time and temperature on 22 serum analytes. Eur J Clin Chem Biochem. 1995;33:231–8. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1995.33.4.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams AE, Kline LM, Dodd RY. Stability of serum alanine aminotransferase activity. Transfusion. 1987;27:431–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1987.27587320539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mijovic V, Contreras M, Barbara JAJ. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and γ-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT) activities in north London blood donors. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:1340–4. doi: 10.1136/jcp.40.11.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chemistry C, Downstate S, Avenue C, Bs CC, Bs ET, Momeni A, et al. Stability of values for the activities of critical enzymes assayed in serum. Clin Diagnostic Pathol. 2017;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ono T, Kitaguchi K, Takehara M, Shiiba M, Hayami K. Serum-constituents analyses: effect of duration and temperature of storage of clotted blood. Clin Chem. 1981;27:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehak NN, Chlang BT. Storage of whole blood: effect of temperature on the measured concentration of analytes in serum. Clin Chem. 1988;34:2111–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeda K, Ichihara K, Hashiguchi T, Hidaka Y, Kang D, Maekawa M, et al. Evaluation of the short-term stability of specimens for clinical laboratory testing. Biopreserv Biobank. 2015;13:135–43. doi: 10.1089/bio.2014.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez Cervera JM, Valero Politi J, Cruz Carlos LM, Monge-Azemar N. Estabilidad de 20 magnitudes bioquímicas: importancia del criterio matemático empleado. Quim Clin. 2015;3512:286. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zander J, Bruegel M, Kleinhempel A, Becker S, Petros S, Kortz L, et al. Effect of biobanking conditions on short-term stability of biomarkers in human serum and plasma. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52:629–39. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyanton BL, Blick KE. Stability studies of twenty-four analytes in human plasma and serum. Clin Chem. 2002;48:2242–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang DJ, Elswick RK, Miller WG, Bailey JL. Effect of serum-clot contact time on clinical chemistry laboratory results. Clin Chem. 1998;44:1325–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuhadar S, Atay A, Koseoglu M, Dirican A, Hur A. Stability studies of common biochemical analytes in serum separator tubes with or without gel barrier subjected to various storage conditions. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012;22:202–14. doi: 10.11613/bm.2012.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwart SR, Wolf M, Rogers A, Rodgers S, Gillman PL, Hitchcox K, et al. Stability of analytes related to clinical chemistry and bone metabolism in blood specimens after delayed processing. Clin Biochem. 2009;42(9):907–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stahl M, Brandslund I. Controlled storage conditions prolong stability of biochemical components in whole blood. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:210–5. doi: 10.1515/cclm.2005.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donnelly JG, Soldin SJ, Nealon DA, Hicks JM. Stability of twenty-five analytes in human serum at 22 degrees C, 4 degrees C, and -20 degrees C. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1995;15:869–74. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2014/10150.5285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimizu Y, Ichihara K. Elucidation of stability profiles of common chemistry analytes in serum stored at six graded temperatures. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019;57:1388–96. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2017-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]