Abstract

The terms practice ready and direct patient care are evolving as the pharmacy profession transforms into a wide-ranging field of highly trained individuals. In a crowded job market, students are seeking opportunities to utilize their training beyond traditional patient care roles. As pharmacy colleges and schools update curricula to reflect current practice and drive this transformation, they are faced with the challenge to accommodate student interest in these growing nontraditional areas with the limit of two non–patient-care elective advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs). This Commentary aims to bring attention to the curricular confinement by accreditation standards on elective APPEs. The time is right as ACPE is gathering input for standards revision. This is a call to action to remove the restriction of non–patient-care elective APPEs, support nontraditional career interests, and enhance opportunities for advocacy, leadership development, and innovation without sacrificing developing proficient direct patient-care skills for all future pharmacy professionals.

Keywords: experiential education, elective, advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE), accreditation, non-patient care

INTRODUCTION

What role does a pharmacist play in the healthcare system? This seems like it should be an easy question to answer, yet it is not as simple as it seems. Phrases such as “practice transformation,” “practice readiness,” and “patient-centered care” have dominated our academic conversations, yet we struggle to define who we really are as a profession.1 While our profession grapples with how to best define our roles in the healthcare community, the need for high-quality care, growth, and innovation continues to increase. The outlook for pharmacy graduates is distinctly different now than it was when the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Standards 2016 were first introduced.2,3 There are not enough traditional roles for hospital and community pharmacists for graduates who have been extensively trained in communication skills, problem-solving, and building relationships.3 While training students to provide optimal patient care is a primary goal of our programs, graduates need to master non-direct patient care skills as well. There has been a call from leadership within the pharmacy profession to recruit, train, and encourage students to be innovative thinkers, creative problem solvers, and influential leaders to ensure our newest graduates possess the necessary skills to transform the practice of pharmacy.4 The supply of traditional pharmacists in the workforce is rapidly exceeding demand, particularly as chain pharmacies are consolidating and reducing labor costs.3,5,6 In 2016, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projected a 10-year growth of 5.6%, from 312,500 to 330,100 pharmacists by 2026, which was 25% below the national employment growth projection of 7.4%.6 More concerning is that the BLS projects a 2% decline in employment of pharmacists from 2020-2030.6 Lebovitz and Eddington raise critical questions about the responsibility of pharmacy colleges and schools to ensure that their graduates secure full-time employment.5 The US Department of Education considers gainful employment to be a reportable outcome and ACPE requires annual reporting of these outcomes by pharmacy colleges and schools.2 Lebovitz and Eddington also cite the importance of innovation and social entrepreneurship, calling on pharmacy schools, associations, and employers to take immediate action that will tip the balance in favor of pharmacists in the future.5

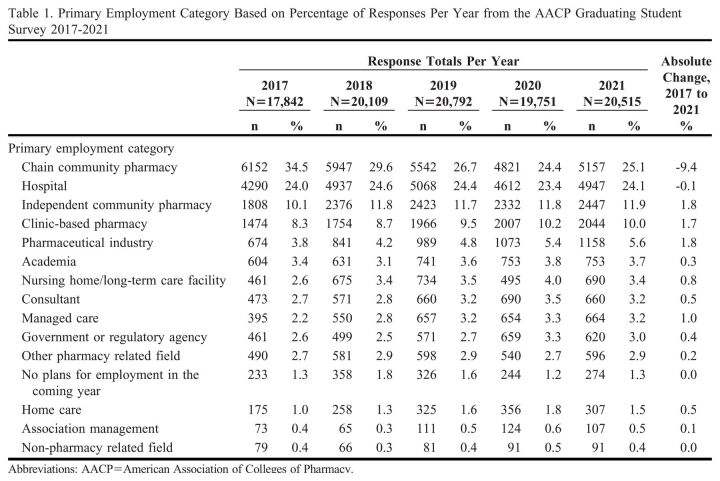

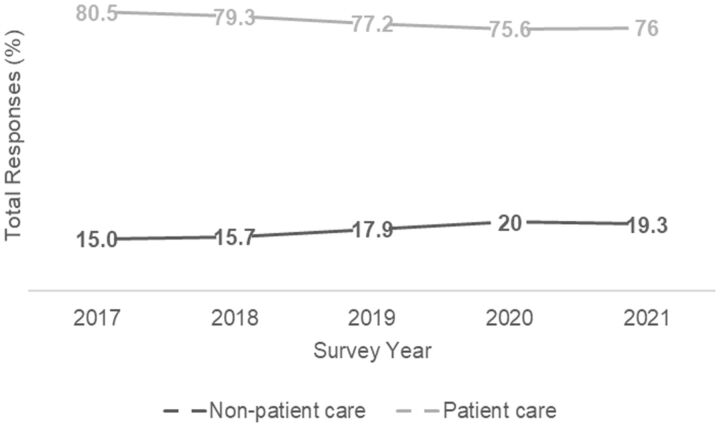

The AACP Graduating Student Survey results from 2017 to 2021 have demonstrated that nontraditional pharmacy opportunities play a significant role in a student’s postgraduation employment plans (Table 1).7 While chain and independent community pharmacies, hospitals, and clinic-based pharmacies remain the top four most-selected practice settings for graduates, the pharmaceutical industry has consistently ranked fifth. Managed care ranked eleventh in 2017 but moved up to eighth in 2021. The largest decrease in percent responses for primary employment was in chain community pharmacy at 9.4% from 2017 to 2021. Additionally, when patient-care–related employment categories (which the authors defined as chain community pharmacy, independent community pharmacy, hospital, clinic-based, home care, and nursing home/long-term care facility) were compared to non–patient-care categories (which included consultant, academia, association management, pharmaceutical industry, managed care, and government or regulatory agency), the percentage of responses that included non–patient-care categories has increased, while the percentage of responses that included patient care categories has decreased over the years (Figure 1). The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) Pharmacy Forecast 2021 advocates for the expansion of pharmacists in leadership roles and health informatics.8 Forecast panelists report that 77% believed very or somewhat likely that a pharmacist will be in an enterprise-wide patient safety leadership role. The ASHP Pharmacy Forecast 2020 reported that pharmacy leaders will likely supervise additional departments. The 2019-2020 Argus Commission argued that flexibility is needed to allow students to specialize in emerging areas and to allow experiential learning to prepare students for these opportunities.9 While these examples were focused on patient-facing experiences, we would like to extend these opportunities to other growing fields that may not be patient-facing experiences. Providing flexibility within elective APPEs is one way to meet this call to action. There is a need for pharmacists to be adaptable, take on new roles and drive practice expansion, yet our current standards may be limiting students’ abilities to practice skills needed for these emerging roles.

Table 1.

Primary Employment Category Based on Percentage of Responses Per Year from the AACP Graduating Student Survey 2017-2021

Figure 1.

Percent of Total Responses for Patient Care Versus Non-patient Care Primary Employment Categories from the AACP Graduating Student Survey 2017-2021.

DISCUSSION

Current Limitations and Challenges

ACPE Standards 2016 state that “time is reserved within the core curriculum for elective didactic and experiential education courses that permit exploration of and/or advanced study in areas of professional interest.”2 The Standards also encourage colleges and schools to provide a variety of APPE electives to allow students to explore areas of potential practice interest, but the Standards limit students to completing a maximum of two non-patient care elective APPEs.2 Given the breadth of career opportunities available to pharmacists and the number of required APPEs in traditional pharmacy roles, this allotment of time for students to identify, select, and experience an elective that better matches their career interest is notably insufficient as this limits their ability to choose from the vast array of available options included in non–patient-care elective APPEs.

This limitation on elective APPEs may hinder a student’s ability to explore nontraditional career paths, even if they have demonstrated achievement of all direct patient care competencies. For example, considering the growth and need for graduates in health informatics, schools that are cautious to count health informatics in the patient care category must then advise the student to choose between health informatics or other electives without being able to fully experience the setting until after graduation. The intention of this limitation may have been to ensure students receive sufficient direct patient care experience. However, there appear to be several flaws in this logic. First, each college and school’s experiential program is uniquely designed, ie, not all students have the same extent of experience across required APPEs. Second, not all students need the same amount of exposure to an area to demonstrate proficiency; each learner is unique. To illustrate this point, according to ACPE’s Guidance for Standards 2016, programs commonly have six to 15 hours of didactic elective courses and one to four elective APPEs. Each school’s unique experiential program design means this restriction on elective APPEs impacts some students more than others. For example, some students have up to 12 weeks (two 6-week blocks) in a non–patient-care focused APPE, where other students are limited to 8 weeks (two 4-week blocks). The limitations placed on electives are unique to pharmacy education as compared to other healthcare professional programs and should be adjusted to ensure that each graduate is competent in patient care skills but also provides the freedom to explore non–patient-facing career paths.

Strategies for Addressing Challenges

Clarifying the definition of a patient care APPE is one strategy to address the limit of two non-patient care elective APPEs. ACPE identifies state or national pharmacy associations, state boards of pharmacy, pharmacy benefit management companies, insurance companies, pharmaceutical manufacturers, drug information or poison control centers, federal/state regulators, and research laboratories as non-patient care sites.2 While drug information and poison control centers may not be patient-facing, they are still patient-focused experiences. Decisions and recommendations made in these settings will directly impact the care the patient receives. By contrast, nuclear pharmacy is sometimes accepted as a patient care elective even though it is not patient-facing. Some managed care sites are considered patient-focused because they impact individual patient care plans, while other sites affect patients in broader ways. These examples illustrate the challenges of categorizing learning experiences as the pharmacy landscape continues to evolve.10 Due to the complicated nature of parsing out the nuances of labeling experiences as “patient care” or “non-patient care,” the task of defining patient care may be more arduous than simply removing the restriction.

Another approach to allow flexibility and career exploration in APPE electives without sacrificing achievement of direct patient care skills is utilizing other tools to ensure competency and removing the limit on non–patient-care electives. Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) are being incorporated into pharmacy school curricula and expected to be integrated into the next version of the ACPE Standards.11 EPAs require schools to ensure competency and practice readiness across all domains for entry-level pharmacists, including being proficient and trusted in the Patient Care Provider Domain. Students will be evaluated on this domain during the four required APPEs and must demonstrate competency to advance and graduate. While many students would be able to demonstrate proficiency during the four required APPEs, others may need additional experiences to ensure competency as a patient care provider. Experiential offices would have flexibility to adjust APPE schedules if students needed additional practice in direct patient care to demonstrate competency.

Balancing Patient Care Skills and Student Interests

Developing guidelines that allow more customized educational experiences without sacrificing the achievement of fundamental patient care skills should be a goal for the ongoing ACPE Standards revision. While all graduates should be expected to demonstrate achievement of patient care skills, creating more freedom for programs to help students explore a variety of career interests during elective APPEs should be encouraged and not limited. We do not assert that there will be a sudden movement for students to have almost all non-direct patient care rotations, nor will it be an option for students who need or desire more direct patient care experiences. We are asking, however, that the new standards accommodate the changing landscape while experiential education offices continue to ensure all outcomes are met prior to graduation. We propose standards that focus on achieving expectations instead of limiting student ability to explore pharmacy experiences. Balancing this freedom with the expectation that programs are assessing and ensuring graduates demonstrate achievement of patient care competencies, and building appropriate remediation policies to address deficits would create a more flexible experiential program. This enhanced model would provide a better experience for students who have career goals not aligned with clinical pharmacy practice and allow programs more flexibility to adjust for the changing needs of the profession more rapidly than waiting for the next iteration of accreditation requirements.

The first priority listed in the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy’s (AACP’s) strategic plan for 2021-2024 is “Leading the Transformation of Pharmacy Practice.” 12 This priority’s goal statements include featuring innovative and emerging practice areas, highlighting enhanced pharmacy practice models, and promoting practice transformation that increases demand and opportunities for pharmacists. We agree with the statement by Lebovitz and Rudolph that “schools no longer have the luxury of promoting the role of a pharmacist as ‘the’ career destination for the PharmD degree, and instead must prepare students to use the skills of their pharmacy education in many different roles.”3 ACPE and pharmacy colleges and schools should encourage rather than limit elective APPEs as a response to these changes in workforce demand and to promote innovation within the pharmacy profession.

Anecdotally, student pharmacists are seeking nontraditional career opportunities and requesting support from their pharmacy programs to broaden their horizons. Colleges and schools of pharmacy have experienced this shift as students request an increase in the number and diversity of student organization chapters on their campuses over the past decade. Student chapters of traditional organizations like the American Pharmacists Association, ASHP, National Community Pharmacists Association, and American College of Clinical Pharmacy are now in the company of the Drug Information Association, Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy, Industry Pharmacists Organization, and International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. Experiential pharmacy education is the perfect opportunity for students to experience these nontraditional areas of practice as potential career paths. As experiential directors, we encourage our students to leverage these opportunities to be immersed in these practice settings before embarking on a singular career path. Limiting elective choices to a maximum of two experiences without a patient care focus unnecessarily limits opportunities for student pharmacists and for the growth of the pharmacy profession. The move toward competency-based education in pharmacy programs provides a framework to assess the development of patient care provider skills while also allowing greater flexibility (and certainly more responsibility) for colleges and schools to individualize a student’s education. Reevaluating experiential education has also been the topic of discussion of the COVID pandemic citing, “The full scope of the impact of the pandemic on experiential education in pharmacy is still unclear, but this situation should serve as a stimulus for innovation and rethinking the paradigm of how pharmacy programs educate and prepare students for pharmacy practice.”13 A commentary by Fulford and colleagues echoes this sentiment to simplify accreditation requirements and move to a more purposeful framework.14 This group of experiential authors adds to this movement with a call to action to permit students to complete a greater variety of experiential electives that support their nontraditional career interests.

CONCLUSION

Since ACPE Standards are undergoing revisions and competency-based EPA assessments are expected to be included in Standards 2025 to guarantee practice readiness, this is the ideal time to remove the non-patient care elective APPE restrictions and allow student pharmacists to explore more nontraditional areas of practice. Training graduates to provide optimal patient care remains a primary goal of our programs. Simultaneously training graduates to be innovative thinkers, creative problem solvers, and influential leaders through broader exposure of nontraditional practice areas is essential for the transformation of pharmacy practice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wagner JL, Boyle J, Boyle CJ, et al. . Overcoming past perceptions and profession-wide identity crisis to reflect pharmacy’s future. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;86(1):Article 8829. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. PharmD program accreditation. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pharmd-program-accreditation/. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- 3.Lebovitz L, Rudolph M. Update on pharmacist workforce data and thoughts on how to manage the oversupply. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(10):Article 7889. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. . Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebovitz L, Eddington N. Trends in the pharmacist workforce and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(1):Article 7051. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook, healthcare occupations, pharmacists, job outlook. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/pharmacists.htm. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- 7.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Research, institutional research, curriculum quality surveys, 2017-2021 Graduating Student Survey National Report. https://www.aacp.org/research/institutional-research/curriculum-quality-surveys. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- 8.DiPiro JT, Fox ER, Kesselheim AS, et al. . ASHP Foundation Pharmacy Forecast 2021: Strategic Planning Advice for Pharmacy Departments in Hospitals and Health Systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(6):472-497. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chase PA, Allen DD, Boyle CJ, et al. . Advancing our pharmacy reformation- accelerating education and practice transformation: Report of the 2019-2020 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(10):Article 8205. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter BL. Evolution of clinical pharmacy in the USA and future directions for patient care. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(3):169-177. doi: 10.1007/s40266-016-0349-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haines ST, Pittenger AL, Stolte SK, et al. . Core entrustable professional activities for new pharmacy graduates. Am J Pharm Educ . 2017;81(1):Article S2. doi: 10.5688/ajpe811S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Preparing Pharmacists and the Academy to Thrive in Challenging Times. 2021-2024 Strategic Plan Priorities, Goals and Objectives. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/aacp-strategic-plan-2021-2024.pdf

- 13.Heldenbrand SD, Smith MD, Malcom DR. A paradigm shift in us experiential pharmacy education accelerated by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(6):Article 8149. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fulford MJ, DiVall MV, Darley A, et al. . A call for simplification and integration of Doctor of Pharmacy curricular outcomes and frameworks [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 10]. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;86(8):ajpe8931. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]