Abstract

Objective. To evaluate third-year pharmacy students’ self-identified preconceptions regarding the term clinical pharmacy as defined by the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP).

Methods. Third-year pharmacy students were led in a multipart activity focused on evaluating their preconceptions about the term clinical pharmacy after exposure to the unabridged definition published by ACCP. Students were asked to identify two preconceptions they had before the activity that were dispelled after reading the article. Thematic coding was used to identify semantic themes and generate summaries of student perceptions.

Results. Three hundred twenty-two third-year pharmacy students’ assignment data was coded to reveal six major themes about their preconceptions related to the term clinical pharmacy: setting, required training, job responsibilities, scope within the health care system, job environment (physical, emotional, financial), and limited knowledge about clinical pharmacy. Consistencies in thought were found within two of these themes, namely setting and required training. Significant variance was seen in the remaining four themes, specifically regarding types of activities performed, job environment, the scope of practice, and impact in the health care system.

Conclusion. Third-year pharmacy students’ preconceptions about clinical pharmacy were related to the exclusivity of where it can be practiced and the need for additional training as a requirement. However, high variability was seen in the majority of the remaining themes, illustrating an inconsistent view of what clinical pharmacy is and the need for intentional focus on professional identity formation within the pharmacy curriculum.

Keywords: clinical pharmacy, student preconceptions, professional identity, pharmacy education, social identification

INTRODUCTION

The pharmacy profession has grown, evolved, and shifted in its professional identity from the apothecary to more current desires to function as independent health care providers focused on the optimization of medication use.1–3 Despite this evolution, distributive tasks still dominate a large percentage of the pharmacy profession, particularly those functioning in a community setting.4 This disconnect between the reality new practitioners face and an ideal vision conveyed by professional organizations, academic institutions, and individual practitioners can lead to significant confusion when students are shaping their professional identity.2

Although several definitions of professional identity formation exist, a report by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) communicates that it “is a process of internalization of a profession’s core values and beliefs and is representative of three domains: thinking, feeling, and acting.”5 Professional identity has been discussed in academic communities as a vital component of how professionals function in their roles. Intentional focus on exploration and construction of professional identity formation during pharmacy school is thought to assist in building a solid foundation of professional behaviors and displayed attitudes desired for a practicing pharmacist.6 Concerns regarding the development of a concrete professional identity surround an apparent lack of a universally accepted and singular identity for the profession of pharmacy.2,7 One core concept at the heart of these concerns is the misconception about what clinical pharmacy is and how it plays into the professional obligations of all pharmacists.

Existing research has focused primarily on perceptions about the role of clinical pharmacy among practicing pharmacists and health care providers.1,3,8,9 Expanding the understanding of concepts, such as the definition of clinical pharmacy, from a student’s perspective may allow an earlier point of intervention to assist with professional identity formation. Given that one of the biggest challenges to professional identity formation within pharmacy involves a conflicting view of the pharmacist as either distributor or clinical specialist, the goal of this study was to evaluate student self-reported preconceptions about the term clinical pharmacy through a series of exercises in a case-based laboratory setting.

METHODS

Qualitative data were collected and analyzed from third-year pharmacy students at the Texas A&M University College of Pharmacy during the fall semester from 2016 to 2018. Data were obtained from student assignments submitted after completing an in-class laboratory activity. The course Rounds and Recitation III is part of a four-semester-long laboratory-based course series.

The laboratory activity was conducted in three parts. First, students played a word association game with the term clinical pharmacy. Students wrote as many words as they could think of when they heard clinical pharmacy, and then they shared and grouped them into themes with their team. Then, students read the unabridged ACCP definition of clinical pharmacy, which defines the term as the discipline where “pharmacists provide patient care that optimizes medication therapy and promotes health, wellness, and disease prevention.” It further highlights the role of the pharmacist in optimizing patient outcomes, generating new knowledge, and caring for patients in all health care settings.10 Finally, after a discussion of the article’s significant findings, students responded to the following question: “Identify two major preconceptions you had about clinical pharmacy dispelled today.” Responses were downloaded from the learning management system and deidentified before analysis.

All student data were retrospectively included unless the two investigators could not interpret the code. Textual data from the individual reflections were collected onto an Excel spreadsheet and underwent an interactive open-coding process for thematic analysis using the content analysis technique by Lincoln and Guba.11 This included individually unitizing the data, identifying unique units of elements, grouping like units into categories, and then identifying overarching categories from themes. Lastly, to ascertain the quality and reliability of the study, investigators compared units, categories, and themes identified. For trustworthiness, two authors carried out the analyses individually and met to discuss coding results and emerging themes. Any areas of discrepancy that were not reconciled between the two authors conducting the analysis were separately reviewed by two additional authors serving as external moderators. Exempt status was granted by the institutional review board at Texas A&M University.

RESULTS

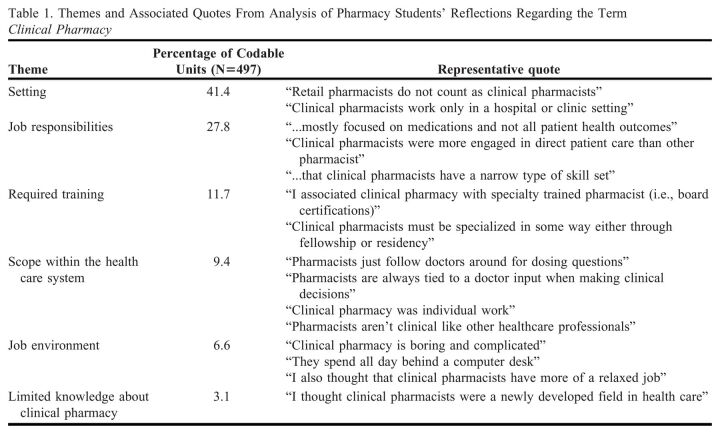

Data from 322 third-year pharmacy students from three cohorts were coded. A total of six dominant themes emerged regarding students’ preconceptions about clinical pharmacy: setting, required training, job responsibilities, scope within the health care system, job environment (physical, emotional, financial), and limited knowledge about clinical pharmacy. Table 1 lists the themes and representative examples.

Table 1.

Themes and Associated Quotes From Analysis of Pharmacy Students’ Reflections Regarding the Term Clinical Pharmacy

The most commonly occurring theme focused on the setting, specifically the location in which clinical pharmacists work. The predominant setting identified included a hospital or institutional pharmacy, with a sparse number of responses also mentioning a clinic setting. In addition, students believed that clinical pharmacy does not apply to all pharmacists, and many even articulated this designation was not applicable to retail or community pharmacy, with one student stating that “only a small number of people become clinical pharmacists” and another mentioning that “retail pharmacists are different from clinical pharmacists.” Another common theme focused on the belief that additional training, such as the completion of residency, fellowships, or other certifications, was required to attain the classification of clinical pharmacist.

Regarding job responsibilities, students primarily communicated a diverse view of the clinical pharmacist’s job responsibilities and were even contradictory in their preconceptions. Many statements in this theme highlighted opposing ideas. Related to the degree of direct patient care as a responsibility, one student wrote, “clinical pharmacists work indirectly with patients to provide health care.” Another stated, “clinical pharmacy was mostly focused on direct patient care.” Despite the contradiction, most students believed that clinical pharmacists had limited direct patient care responsibility. Other areas articulated here suggest that students thought clinical pharmacists were generally very medication focused instead of focused on generating new knowledge, optimizing patient outcomes, or integrating economic principles into their decision-making. These are illustrated by the following student responses: “I was under the impression that clinical pharmacists generated SOAP [subjective, objective, assessment, plan] notes all day long”; “I did not consider that clinical pharmacists were involved in research”; “Clinical pharmacists are mostly focused on medications and not all patient health outcomes.”

Another theme illustrating a diversity of perspective was the clinical pharmacist’s impact and scope in health care. Most students thought that clinical pharmacists had limited autonomy in their decision-making capabilities or their ability to impact patient outcomes. Various articulations of this theme related to the idea that pharmacists play a more submissive role in patient care compared to physicians, with one student stating, “I did not think we functioned independently.” Additionally, students conveyed contrasting views of whether they work alone versus only as part of a team, with examples such as “clinical pharmacists only work independently” and “I expected clinical pharmacists to only work in a team.”

Another theme that arose was the job environment, which illustrates students’ preconceptions about the physical, financial, and emotional work environment. Both negative and positive attributes were articulated, but most of the statements in this category did reflect a more negative slant on their preconceptions, with comments such as “they just sit at a desk” or “seems boring.” Compensation was also communicated as a negative job environment factor, with most preconceived notions revolving around less pay.

Finally, as the last theme, students expressed a lack of knowledge or limited understanding of clinical pharmacy, illustrated by the examples, “I held a very narrow view of what clinical pharmacy was” and “vague concept for me.”

DISCUSSION

The themes identified in this study provide perspective on pharmacy students’ professional identity formation related to the concept of clinical pharmacy. They illustrate the dissonance between a professional vision of all pharmacists being considered clinical and their lived experience. These students conveyed similar perceptions about the clinical pharmacy setting and the need for additional required training but displayed high variability in their perceptions about job responsibilities, environment, and scope of the clinical pharmacist within the health care system.

Previous studies have shown students have a limited understanding of the roles and responsibilities of a pharmacist prior to entering pharmacy school.12,13 Two themes, setting and required training, illustrate a consistent thread classifying the clinical pharmacy identity to a specific group of pharmacists rather than the entire profession. Although additional training is typically required after graduation to obtain a pharmacy position encompassing predominantly clinical responsibilities, the view related to the exclusivity of setting is in direct opposition with voices within the profession pushing for all pharmacists to be considered clinical.14

On the other hand, findings from three themes articulated in this study convey a diversity of answers related to the clinical pharmacist’s responsibilities, environment, and scope. A gap between the idealistic descriptions taught and the enacted duties they see in practice may explain some of the inconsistencies in these areas. Professional identities emerge throughout a learner’s training as a combination of existing personal identities and socialization within the community of practice.15 The themes identified likely reflect a combination of personal identities and direct or indirect messaging from pharmacists they have engaged with through work experience or experiential learning environments. Given the varied perspectives on practice within the profession, it is no surprise these students reflect this as well.

The findings illustrate an opportunity to engage in more intentional conversations and educational activities focused on supporting students in the often invisible process of identity formation. Prior studies have highlighted the need for a multipronged approach encompassing early professional socialization, clear curriculum alignment with work practices, and intentional leveraging of the co-curriculum.5,7,16 The authors of those studies believe that woven throughout these approaches should be longitudinal reflections and discussions about the dissonance seen in their didactic and experiential curricula.16 Authentic conversations and activities should be directed at engaging students in addressing the gap between ideological goals portrayed by professional organizations and the reality of the challenges they face upon graduation. Activities such as the one outlined in this study may serve as an entry point for creating an environment of discovery needed for problem-solving and creative decision-making. This activity created an open dialogue between students and the faculty instructor regarding students’ current preconceptions of the term clinical pharmacy. It also exposed students to an external professional definition of the concept and allowed them to reexamine their preconceived notions compared to the external professional articulation of the concept.

This study possesses several limitations. First, the data were collected from a single pharmacy school, limiting generalizability to other colleges, especially related to differences seen in professional socialization. These findings would apply to other schools of pharmacy that have had no conversations directed at intentional development of students’ professional identity formation. However, given the consistency with findings across three years of data analysis, we expect durability with the identified themes. The directed-response nature of the assignment did not allow for an opportunity to probe for rationale or explanation related to each preconception, especially related to detecting the potential origin of this information. Additionally, the assignment requested that students list only two preconceptions, which may have limited the number of themes identified. Further, the form of the question on the assignment may have impacted some interpretation of the data, as several students articulated their answer as an evolution of their thought rather than stating what they believed before the activity took place. Finally, the identification of preconceptions was limited to those articulated in ACCP’s unabridged definition of clinical pharmacy, so there may be an expanded list of themes if a different definition of the term is used. Further studies are needed to articulate the origin and evolution of these views.

CONCLUSION

Third-year pharmacy students identified their own preconceptions about clinical pharmacy regarding the setting, responsibilities, environment, scope in the health care system, job environment (physical, financial, and emotional), and required training. The inconsistencies seen within most themes conveyed a disjointed and even contradictory picture of what the pharmacy profession defines as clinical pharmacy. This study highlights the need for more authentic conversations with students about this cognitive dissonance between professional ideals and the current systems that constrain the profession. Integrating activities like the one outlined in this study can build a starting point for these conversations. Further studies on the origin of these preconceptions and their evolution over time may help create a more targeted approach to positively impact professional identity development during pharmacy school.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scahill SL, Atif M, Babar ZU. Defining pharmacy and its practice: a conceptual model for an international audience. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2017;6:121-129. doi: 10.2147/IPRP.S124866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kellar J, Paradis E, van der Vleuten CPM, Oude Egbrink MGA, Austin Z. A historical discourse analysis of pharmacist identity in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(9):ajpe7864. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elvey R, Hassell K, Hall J. Who do you think you are? Pharmacists’ perceptions of their professional identity. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(5):322-332. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witry MJ, Arya V, Bakken BK, et al. . National pharmacist workforce study (NPWS): description of 2019 survey methods and assessment of nonresponse bias. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(1). doi: 10.3390/pharmacy9010020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welch BE, Arif SA, Bloom TJ, et al. . Report of the 2019-2020 AACP Student Affairs Standing Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(10):ajpe8198. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mylrea MF, Gupta TS, Glass BD. Professionalization in pharmacy education as a matter of identity. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(9):142. doi: 10.5688/ajpe799142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noble C, McKauge L, Clavarino A. Pharmacy student professional identity formation: a scoping review. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2019;8:15-34. doi: 10.2147/IPRP.S162799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenthal MM, Breault RR, Austin Z, Tsuyuki RT. Pharmacists’ self-perception of their professional role: insights into community pharmacy culture. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2011;51(3):363-367. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2011.10034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schindel TJ, Yuksel N, Breault R, Daniels J, Varnhagen S, Hughes CA. Perceptions of pharmacists’ roles in the era of expanding scopes of practice. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(1):148-161. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):816-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lincoln YS, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1st ed. SAGE Publications; 1985:416. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinn G, Lucas B, Silcock J. Professional identity formation in pharmacy students during an early preregistration training placement. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(8):ajpe7804. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloom TJ, Smith JD, Rich W. Impact of pre-pharmacy work experience on development of professional identity in student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(10):6141. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans A. We are all clinical pharmacists. Pharmacy Times. Decemeber 4, 2017. Accessed April 11, 2023. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/we-are-all-clinical-pharmacists [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718-725. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clandinin DJ, Cave M-T. Creating pedagogical spaces for developing doctor professional identity. Med Educ. 2008;42(8):765-770. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]