Abstract

Obstetrics is a well-known area for malpractice and medical-legal claims, specifically as they relate to injuries the baby suffers during the intrapartum period. There is a direct implication for nurses’ work in labor and delivery because the law recognizes that monitoring fetal well-being during labor is a nursing responsibility. Using institutional ethnography, we uncovered how two powerful ruling discourses, namely biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses, socially organize nurses’ fetal surveillance work in labor and delivery through the use of an intertextual hierarchy and an ideological circle.

Keywords: obstetrics, nurses’ work, patient safety incidents, intertextual hierarchy, ideological circle, Canada

Introduction

Medical-legal risk is a dominant discourse in obstetrical care. In fact, Accreditation Canada, Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC), Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA), and Salus Global Corporation (2016), and the Canadian Nurses Protective Society [CNPS] (CNPS, 2002), confirms obstetrics is well established and well known as a high-risk practice domain with malpractice or negligence lawsuits being quite common, particularly in relation to fetal health surveillance during labor. Perinatal nursing is considered a specialized area (Canadian Nurses Association (CNA), 2021) which implies a higher standard of care because a more specialized set of skills and knowledge are required, including fetal health surveillance. Hence, there is a direct implication for nurses’ work in labor and delivery because—according to CNPS (2002)—the law recognizes that monitoring fetal well-being during labor is a nursing responsibility. Additionally, the Canadian Association of Perinatal and Women’s Health Nurses (CAPWHN) offer a set of practice standards and guidelines that includes the SOGC Fetal Surveillance: Intrapartum Consensus Guideline (Dore & Ehman, 2020). Labor and delivery nurses are also be held to these standards.

The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate how this medical-legal risk discourse trickles down through a textually-mediated hierarchy which serves to regulate labor and delivery nurses’ fetal health surveillance work at the local unit level. Here, we report on findings specific to the ruling relations or extra-local forces that influence how nurses “do” fetal health surveillance and coordinate their work in labor and delivery. This investigation is part of a larger study which Kelly completed as part of her doctoral program which also included uncovering what actually happens when labor and delivery nurses conduct fetal health surveillance work (Kelly et al., 2022). Our entry point into the study began at the local unit level; specifically, in an urban tertiary care labor and delivery unit within an Eastern Canadian province. We maintained the standpoint of labor and delivery nurses’ as people’s experiences and knowledge offer hints that enable researchers to trace what happens in the regime of ruling (Rankin, 2017). A significant finding from this first phase was discovering how the powerful biomedical discourse influences how health care providers, including nurses, mange intrapartum care. Based on findings at the unit level, we wanted to understand how these extra-local ruling forces actually influence and organize nurses’ fetal health surveillance work. To uncover these ruling relations, we followed “clues” (M. Campbell & Gregor, 2008, p. 81) that were obtained from the local site. In doing so, we moved beyond the local unit setting, work experiences, and knowledge of local nurse informants, to an examination of the extra-local social organization of ruling.

Our investigation led us to elucidate how the biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses influence as ruling relations or ruling discourses. The research question for this paper was: What social relations organize and influence how labor and delivery nurses conduct fetal health surveillance? The analytic approach used in this exploration was a critical feminist methodology– institutional ethnography (IE) developed by Dorothy Smith, a Canadian feminist sociologist. This qualitative methodology generates knowledge of how things happen as they do and makes apparent the social organization of people’s work (D. E. Smith, 2005, 2006). A more in-depth description of the methodology is available elsewhere (Kelly et al., 2022). Through the use of two major analytical tools unique to IE, intertextual hierarchy and ideological circle, we uncovered how these two ruling discourses socially organize nurses’ work in labor and delivery.

Institutional Ethnography

The underlying assumption of institutional ethnographers is that people are the experts in how they live their lives. The aim of IE research is to see, hear, and understand people’s everyday life experiences and then to use this understanding as the means to figure out how things are coordinated to occur so that steps can be taken to implement change (Deveau, 2016; D. E. Smith, 1987, 2005). People are located in a network of social relations comprised of sites (local settings) throughout society. Powerful outside (extra-local) forces shape how people live and experience their everyday lives, often without their explicit knowledge or understanding (M. L. Campbell, 1998). The extra-local forces are referred to as ruling relations that intersect, order, control, and coordinate the activities and actions of people at the local setting often in ways they are not aware of (DeVault & McCoy, 2002; D. E. Smith, 2001). Ruling relations, in addition to bureaucracies, administration, and professional discourses, may include corporations and mass media (Devault & McCoy, 2006; D. E. Smith, 2005). This coordination of people’s purposeful activities (i.e., work) occurs on a wide scale that spans across time and geography, and involves multiple sites and people, who do, or do not, know each other, and may, or may not, meet face-to-face (Devault & McCoy, 2006).

Textually-Mediated Discourse

Discourse refers to “a systematic way of knowing something that is grounded in expert knowledge and that circulates widely in society through language, including most importantly language vested in texts” (Mykhalovskiy, 2002, p. 39). Discourse is embedded in the ways individuals think and communicate about people, things, and the social organization of society and the relationships among and between all three (Cole, 2020). While the subject of discourse is often heavily influenced by Foucault’s use of the term and the characteristic form of power it signifies, D. E. Smith’s (2005) conceptualization is more active whereby discourse does not lose sight of the subject. In other words, Smith credits people’s use of language, speech, writing, and ideas as the means by which discourse is maintained, perpetuated, and reproduced. For example, the nurses in this study perpetuated dominant biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses by how they talked about, described, viewed, and approached childbirth and how they provided care for laboring women.

D. E. Smith (1999) contends that texts are chiefly responsible for maintaining, perpetuating, and reproducing discourse. Texts enable domination of discourse by bridging extra-local ideology with local settings because “both in their materiality and symbolic aspect (texts) form a bridge between the everyday/everynight local actualities of our living and the ruling relations” (D. E. Smith, 1999, p. 7). Examples of texts are formal policy documents, media reports, patient charts, videos, auditory recordings, social media, computerized programs, or newspapers. IE researchers treat texts as “material artifacts that carry standardizing messages” (Bisaillon, 2012, p. 620). It is through texts that ruling relations coordinate and disseminate discursive ideologies (D. E. Smith, 1990a). Texts convey the ruling discourses to various people, in myriad locations, at different times. In other words, the discursively organized relations embedded within the texts that people use routinely, infuse their thoughts, understandings, and the activities of their everyday life. Hence, texts are essential because they function as the main tools of ruling (Rankin, 2017). It is important to note that “texts do nothing on their own” (Frampton et al., 2006, p. 38) but are made active by people referring to, reading, filling out, responding to, or reproducing their content (Doll & Walby, 2019).

Data Collection

The number of informants in an IE investigation is not specified, instead the focus is to recruit enough informants in order expose the ruling relations across different times and places (Devault & McCoy, 2006). In order to expose these ruling relations, Kelly paid very close attention to what documents the nurse informants referred to when they described how they conducted their work (Kelly et al., 2022). The texts referred to by the nurse informants directed Kelly to recruit certain health care informants from both the regional health authority’s management and administrative teams (n = 5) and one health care provider who represented a national multidisciplinary professional organization. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from both the Newfoundland and Labrador Health Research Ethics Board (Reference Number 2019.030) and the regional health authority Research and Proposal Approval Committee (Reference Number 2019.0303). Written consent was obtained from all informants who agreed to participate in the study.

All data were generated by Kelly in 2019 through face-to-face and telephone, semi-structured, digitally recorded interviews. Informant interviews lasted from 60 to 75 min in length, were audiotaped and digitally transcribed, de-identified to maintain anonymity and confidentially. Interview questions were formulated to allow us to discover specific key documents (texts) that extra-local informants draw on to inform lower level institutional texts which nurses’ use to inform their work at the local unit level. When informants referred to particular documents, they provided Kelly with clues as to which texts that needed to be obtained and examined. Kelly paid very close attention to the discourse of dominant ideology that was embedded in the documents informants spoke and referred to because this dominant discourse often plays a major role in shaping organizational culture, values, and agendas (Devault & McCoy, 2006).

Data Analysis

In IE investigations, data collection and analysis occur simultaneously (M. Campbell & Gregor, 2008). Here, Kelly immersed herself in the data which involved iterative reading and re-reading of transcripts looking for specific documents referred to by the informants. Through analysis of these documents we were able to detect traces of ruling relations and organizational texts in national clinical practice guidelines, patient safety programs, hospital insurance documents, nursing regulatory standards, institutional policies, and patient charts forms/flowsheets using unique IE analysis techniques. IE researchers understand that texts do not stand alone and are not independent of other texts. Instead, there is an interdependence of texts within a hierarchy. This is known as intertextual hierarchy in which higher level texts control and shape lower level texts (D. E. Smith, 2005). Ideological circle was the second analytic technique employed within this phase of the study. The ideological circle is a form of coordination that brings people’s front-line work in line with institutional objectives through their activation of texts (Grace et al., 2014). When people make texts active, they read, document and/or make use of them. Activation of texts makes the ideological circle an identifiable and traceable sequence of institutional action by front-line workers translating everyday actualities into managerial texts which become stand ins for whatever is actually happening (Griffith & Smith, 2014). Standardization of front-line work occurs. Both analytic techniques helped us to “weave the analysis together to show how the ruling relations work as generalizing practices and unfold in similar ways for variously located people across different sites and times and in different situations” (Rankin, 2017, p. 8).

Findings

The findings presented here demonstrate how nurses’ work in labor and delivery is socially organized by the biomedical and medical-legal risk ruling discourses. From here, we elucidate how this happens through an intertextual hierarchy and ideological circle.

Obstetrical Biomedical Model as a Ruling Discourse

The biomedical model originates from medicine and medical work. At the core of this model is diagnosis and treatment of disease or illness. It is founded on three principles: (a) diseases are pathological conditions caused by biological, chemical, and, or, physical factors; (b) advances in technology and randomized controlled trials produce the best evidence for patient care; and (c) disease is a dysfunction of particular body parts (e.g., organs, tissues, cells) (Valles, 2020). Based on these principles, biomedicine has adopted a mechanical metaphor for the human body; it is a machine and physicians are engineers or repair persons ready to fix body parts that malfunction (Nettleton, 2020). This results in the body being interpreted as merely a collection of mechanical systems composed of cells, tissues, and bio-chemicals (Benner, 2000).

During our IE exploration it became evident that the biomedical model exerts influence as discourse in all aspects of intrapartum care (Kelly et al., 2022). For decades, childbirth has been evolving into a bio-medical event. Subsequently, care is often provided as if the birthing process is pathologically dysfunctional rather than a normal, healthy event (Zwelling, 2008). Modern obstetrical care within hospitals often subjects women to institutional routines and medicalized and technological interventions (Bohren et al., 2017; Romano & Lothian, 2008; Zwelling, 2008) with an underlying obstetrical science credited by practitioners to minimize risks (Chadwick & Foster, 2014) of adverse outcomes (Bisits, 2016). Risk surveillance begins as soon as pregnancy is confirmed and continues throughout pregnancy, and the intrapartum period. For instance, Kelly et al. (2022) discovered how the obstetrical health care team activated specific risk discourses to commence the use of the continuous electronic fetal monitor during women’s low-risk labors which subjects women and their babies to increased rates of instrumental vaginal and operative births.

The birthing process is merely mechanical if viewed through the lens of the biomedical model (Davis-Floyd, 2001). The process is inherently defective and thus in need of specialized medical monitoring. In addition, laboring women are objectified, void of thought or feeling, and as such, it is expected that women will be readily exposed to insertion of intravenous infusions, monitors, and catheters. More believable information regarding labor and birth must therefore be obtained from sophisticated technological machines than that attained through the senses or through women’s verbal reports. All these measures are deemed necessary to achieve good birth outcomes. For example, the use of the continuous electronic fetal monitor provides vital information related to fetal well-being during labor. The electronic fetal monitor machine can wirelessly transmit data to monitors outside the birthing room. Centralized fetal monitoring at the nurses’ station means nurses can view screens showing data related to the status of the fetus, (Goldberg, 2002), and nurses do not have to be present at the bedside collecting data related to the status of the laboring woman.

Most women in Canada deliver their babies within hospital environments (Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI], 2020) and are under the care of either obstetricians (58%) or family medicine physicians (34%). A small percentage are under the care of midwives (6%) (Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC], 2020). Registered nurses who work on labor and delivery units care for mothers during labor and birth (Van Wagner, 2016). The tertiary care center within which our IE exploration took place offers care for women experiencing either low- or high-risk pregnancies including triage, and labor and delivery services for the entire province. It is important to note that no midwives are currently employed within this health authority. While both obstetricians (n = 14) and family medicine physicians (n = 7) provide all the maternity services, most women are cared for by obstetricians, obstetrical residents, and medical students. This is concerning as obstetricians are considered to be high risk specialists who receive advanced education and training related to complex pregnancy and birth conditions (Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, 2019).

Medical-Legal Risk Discourse

Another discourse uncovered during this IE exploration is medical-legal risk discourse. Medical legal risk discourse is founded on health care, the law, the responsibilities of health care providers (e.g., physicians, nurses), and the rights of patients. Each province has a legislated governance structure and disciplinary procedures for the nursing profession, primarily through the Registered Nurses Act (2008). Legislation governs the nursing profession and serves to ensure that nurses’ decisions and actions are consistent with current legal standards. It also acts to protect nurses from liability, and at the same time, protect the public (patients) who receive nursing care. The law requires nurses to be competent and safe. Nurses are held legally accountable for their actions and can be involved in legal proceedings including professional discipline, civil lawsuits, criminal prosecutions, and grievances (CNPS, 1999, 2020; Kozier et al., 2018). As a matter of fact, Kelly et al. (2022) uncovered that the major concern for many of the nurse informants was their fear of professional discipline, losing their license to practice and, or, their job, and being named in civil lawsuits.

In malpractice cases, the patient (plaintiff) alleges harm caused by the actions or inactions of the named defendant(s) and seeks money as compensation for injuries suffered while in the care of the defendant(s) (CNPS, 2007). If nurses are identified in a civil lawsuit, they are usually represented by the employer’s lawyer since nurses are employees of a hospital or health authority. This identification or naming of nurses constitutes an allegation of negligence (CNPS, 2004). Negligence is defined as the nurses’ failure to provide the care that a prudent nurse with the same credentials would provide in similar circumstances and according to a certain set of standards (Shaprio, 2019). Nurses are found liable for negligence if it is established that the nurse owed a duty of care to the patient; the nurse did not carry out that duty; the patient was injured; and the nurse’s failure to carry out that duty caused the injury (Shaprio, 2019). The following is a synopsis of how this occurs: harm is inflicted on the patient; it is determined the cause is a breach in the standard of care based on evidence introduced by lawyers involved in the lawsuit; and examples of the evidence to determine standard of care include the patient’s chart, professional standards of practice, institutional policies, and testimony from those involved in the case or those with knowledge about the unit’s functioning (CNPS, 2004, 2007).

Activation of Medical-Legal Risk Discourse

Health care institutions (hospitals) work together with the Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI) 1 and put in place measures to minimize risk and subsequent harm occurring to patients (women) during their hospital stay (intrapartum experience). However, despite these safety measures being in place unfavorable outcomes do occur. Similarly, when society views pregnancy as a natural event any unexpected or adverse outcome could result in allegations of negligence. This creates a paradox between society’s natural perspective on birth and health care provider’s risk perspective. In a study conducted by Kornelsen and Grzybowski (2012) exploring perceptions of risk related to childbirth in rural communities of British Columbia, the researchers discovered that both nurses and physicians tended to view the potential for adverse outcomes as a reason for transporting women out of their rural communities and into tertiary care centers. They worried that if women remained in rural communities for their labor and delivery experience, there was the potential for “community backlash” (p. 5) if poor birth outcomes occurred. However, transport out of the community created social stress for women that was associated with leaving family and social supports behind.

Nevertheless, poor obstetrical outcomes can trigger activation of medical-legal discourse. The majority of birth trauma cases that lead to medical malpractice claims are the cases when the baby suffers a brain injury (Miller, 2017). When this type of adverse outcome occurs during childbirth families are encouraged to sue due to the financial costs placed on the family involved in care needs (Rokosh, 2020). Lawyers who represent the families in these cases typically sue for liability and damages which can result in multimillion-dollar settlements due to the life-long expenses required to care for the child (Rokosh, 2020).

Intertextual Hierarchy

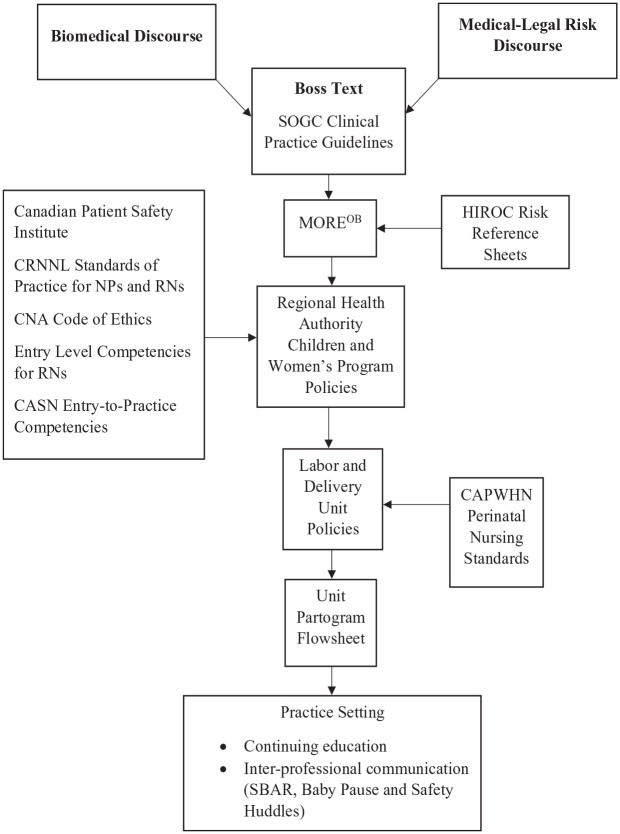

We uncovered that ruling discourses are positioned at the top of the social organization of nurses’ work in labor and delivery (Kelly et al., 2022). The intertextual hierarchy in Figure 1, illustrates the infiltration of biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses through an interconnected textual pathway beginning with the boss text. The intertextual hierarchy of organizations are constructed by “boss texts” (D. Smith & Turner, 2014, p. 10) which are explained by D. E. Smith (2006) as the regulatory or higher order texts. Boss texts regulate, govern, and standardize subordinate level texts within organizations (Doll & Walby, 2019).

Figure 1.

Intertextual hierarchy.

Note. CAPWHN= Canadian Association of Perinatal and Women’s Health Nurses; CASN = Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing; CNA = Canadian Nurses Association; CRNNL = College of Registered Nurses Newfoundland and Labrador; HIROC = Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada; NPs = nurse practitioners; RNs = registered nurses; SOGC = Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Canada.

Boss Text: Society of Obstetricians Gynecologists Canada

SOGC clinical practice guidelines (e.g., Fetal Health Surveillance Intrapartum Consensus Guideline, 2020) is one of the boss texts that governs the management of intrapartum care, fetal health surveillance, and is foundational to organizational texts discovered in our study. In fact, the SOGC clinical practice guidelines are the boss texts that hierarchically orders organizational unit policies, standards, and patient chart forms (e.g., the partogram flowsheet) that are routinely used by nurses during the care of laboring women. As explained by D. E. Smith (2006), the boss text “governs the work of inscribing reality into a documentary form by providing a discursive frame for those working in organizations, hence, orientating their observing and report writing work to certain elements of local actualities” (p. 65). Consequently, as nurses engage with these texts, they also activate the ruling biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses.

The SOGC is a national specialty group founded by physicians whose goal is to promote excellence in the practice of obstetrics and gynecology and to advance the health of women. The organization is considered to be the national leader in offering evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (Blake & Green, 2019). However, it is important to note that institutional uptake of these guidelines is not mandated and hence does not require health care providers to abide by them. Nevertheless, because they are developed based on the “best” available medical evidence, they have become the leading authority and form the basis for practice policies and the standards expected for medical and nursing practice across Canada. One of our study informants representing SOGC explained,

The guideline is as good as people who read it and how it gets implemented at the hospital level. This is what we recommend based on best evidence and where there is a lack of evidence based on professional consensus. So, what we hope the organizations will do, read SOGC guidelines is to adopt them and say, ‘okay here’s the guidelines, we adopt this, we formally adopt this as a policy for our organization and this is how we enact it as a policy.’ So, then it becomes an organizational policy. So, nurses are then required to practice within their organizational standards and their policies. (Informant, SOGC Representative)

We found it extremely significant that there was an absence of professional nursing organizations such as the Canadian Association of Perinatal and Women’s Health Nurses (CAPWHN), the Association of Women’s Health Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) and perinatal nursing practice standards at this level of the intertextual hierarchy. Interestingly, all the informants referred to the SOGC organization as their main references and sources of knowledge that influences and informs unit policies, procedures, and how they carry out their work.

The SOGC clinical practice guidelines also inform a textually-mediated educational program (MOREOB) that is centered on the provision of obstetrical care. The MOREOB program that was originally developed by the SOGC (Blake & Green, 2019) is the next text within the intertextual hierarchy and flows from the boss texts.

MOREOB Program

MOREOB is an interdisciplinary obstetrics risk and error reduction program utilized in many hospital birthing units across Canada. This program was developed by Dr. Kenneth Milne, then the acting vice president of the patient safety division of SOGC. After a successful pilot of the program in various Canadian hospitals in 2002, SOGC approached the national hospital insurance provider Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC) to help bring the underlying principles embedded in the MOREOB program to other clinical areas. With both organizations sharing a common interest of improving patient safety, they formed Salus Global Corporation 2 where MOREOB is now housed.

The MOREOB program aims to create a culture of safety in obstetrical units by using high reliability organization principles (MOREOB, 2019). High reliability organizations stem from work done in the 1970s whereby high risk industries and complex systems (e.g., aviation and nuclear power) minimized risk and consequently reduced catastrophic mistakes (Cooper et al., 2016). A key feature of high reliability organizations is their preoccupation with failure and their focus on both prevention and containment of risks (Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada [HIROC], 2017). High reliability organization principles include awareness of systems that influence patient care and outcomes, a culture that promotes an organization and teamwork, and a commitment to ongoing training and learning (Reszel et al., 2019). The focus is on the care of pregnant women in hospitals with emphasis on teamwork, effective communication, interdisciplinary education (e.g., for nurses, midwives, family physicians, obstetricians), opportunities to review normal and abnormal events, and the involvement of health care providers in skills practice and emergency drills. The program claims to bring together most health care providers in the labor and delivery unit through educational workshops and alleges to provide the means to eliminate a culture of blame in hospitals. The MOREOB program uses a “train the trainer” approach where a core interdisciplinary team is recruited by the hospital and is trained and supported by Salus Global to implement the program. A series of hands-on evidence-based workshops and readings, designed to improve birth outcomes, are included. Many of the MOREOB educational workshops focus on adverse events and are informed by the SOGC’s clinical practice guidelines.

The program includes three evidenced–based modules: Learning Together, Working Together, and Changing the Culture (Reszel et al., 2019). Each module is expected to be completed over a period of 1 year with all members of the health care team jointly participating at the same time. Fetal health surveillance education is included in one of three modules and is divided into two separate chapters. The initial chapter reviews and discusses the following biomedical knowledge in great detail: fetal and utero-placental circulation and physiology, oxygenation of the fetus, factors that impact on fetal oxygen levels, fetal hypoxia, factors associated with cerebral palsy, and neonatal encephalopathy. The second chapter addresses material specific to fetal health surveillance during labor. It is interesting to note that the first MOREOB workshop held at this site was on fetal health surveillance and included practising how to interpret and classify fetal heart rate tracings.

The regional health authority initiated the MOREOB program in 2018. Large posters displayed throughout the labor and delivery unit publicize the MOREOB program for health care providers and visitors. These posters acknowledge the high-risk nature of obstetrical care and are also intended to act to provide public assurance that the regional health authority is committed to achieving safe outcomes for mothers and their babies.

HIROC Risk Reference Sheets

Situated at the same hierarchical level as the MOREOB program, is the Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC), which provides insurance for health care institutions and, as part of its’ mandate, is also focused on safety in health care. HIROC highlights patient safety knowledge from insurance claims and makes this knowledge available to health care institutions and practitioners (Accreditation Canada, Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC), Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA), and Salus Global Corporation, 2016) through the development of a list of the top leading risks of the costliest claims within hospitals. These risks are published in Risk Reference Sheets and are available on the HIROC website. Through the Risk Reference Sheets, HIROC offers strategies to reduce the general risk of patient safety events and makes recommendations to regional health authorities to put in place patient safety practices that reduce adverse events from occurring in labor and delivery. Patient safety practices include the implementation of the national MOREOB program in the obstetrical program. Obstetrical risks, namely those related to fetal health surveillance are among the top risks within acute care settings (Accreditation Canada, Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC), Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA), and Salus Global Corporation, 2016).

Regional Health Authority Children and Women’s Program Policies

Moving down the intertextual hierarchy are the regional health authority policies specific to the children and women’s program. According to the website, the program provides primary, secondary, and tertiary care services to children (up to 18 years of age) and to women requiring obstetrical or gynecological services throughout the province. Within the program, well over 10,000 women and children receive medical care each year. This is accomplished by developing higher level, broad, and comprehensive policies that are extensive and specific enough to be implemented at various sites within the program. Evident in the hierarchy is how the children and women’s program policies flow from the SOGC clinical practice guidelines and MOREOB program. For example, the children and women’s health program’s electronic fetal monitoring policy requires any health care provider (e.g., nurses) who performs continuous electronic fetal monitoring, to interpret, classify, and record findings according to the SOGC Fetal Health Surveillance: Intrapartum Consensus Guideline (Dore & Ehman, 2020), including documentation of communication with the physician in the patient chart (e.g., progress notes). These guidelines are also taught during the MOREOB fetal health surveillance workshops.

Canadian Patient Safety Institute

Continuing at the same hierarchical level and influencing the regional health authority’s children and women’s program policies is the Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI). This institute was established by Health Canada in 2003 and is a nationally funded organization that works with governments, health organizations, leaders, and health care providers to promote improvement in patient safety (Canadian Patient Safety Institute [CPSI], 2021a). The CPSI website outlines specific tools and resources to prevent patient safety incidents. Of the many harm reducing strategies and approaches offered, the Hospital Harm Improvement Resource (CPSI, 2021b), proposes specific practices to prevent unintended outcomes (harm) occurring to patients while hospitalized. A compilation of evidence-informed practices is provided for health care providers to consider that could improve patient safety and prevent adverse events from occurring.

Nursing Regulatory Standards

Located at the same hierarchical level to inform regional health authority children and women’s program policies, are regulatory standards. Registered nurses in all provinces and territories are regulated by provincial regulatory bodies. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the regulatory body for registered nurses is the College of Registered Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador (CRNNL). The mandate of the CRNNL is to protect the public through self-regulation of the nursing profession as prescribed by the Registered Nurses Act (2008) As such, the CRNNL has the legislative authority to set standards. For example, The Standards of Practice for Registered Nurses and Nurse Practitioners (2019b) establishes “the regulatory and professional foundation for nursing practice” (p. 2). This document consists of four standards which registered nurses (and nurse practitioners) must follow in all practice roles. Similarly, the CRNNL released new Entry-Level Competencies (ELCs) for the Practice of Registered Nurses (2019a). This document was developed in collaboration with other Canadian nurse regulators and was updated to “ensure inter-jurisdictional consistency and practice relevance” (p. 1). The CRNNL outlines seven overarching principles informing what is expected of entry-level registered nurses and highlights how they are prepared as generalists to practice safely, competently, compassionately, and ethically, through evidence-informed practice. In addition, nurses are ethically mandated by the Code of Ethics to provide safe, competent, compassionate and ethical nursing care (Canadian Nurses Association [CNA], 2017). Other formal professional nursing organizations such as the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN) who represent undergraduate and graduate nursing programs in Canada, published Entry-to-Practice Competencies for Nursing Care of the Childbearing Family for Baccalaureate Programs in Nursing (2017). This document reflects the core competencies related to the nursing care of childbearing families that all baccalaureate nursing students in Canada should acquire over the course of their undergraduate education. Specifically, Indicator 2.6 requires nursing students to provide evidence-informed nursing care in relation to common perinatal health concerns during pregnancy (p. 10).

Labor and Delivery Unit Policies and the Partogram Flowsheet

Continuing down the hierarchy and flowing from the regional health authority children and women’s program policies are the specific labor and delivery unit policies and the partogram flowsheet. The policies and patient chart forms (i.e., flowsheets) are unique to the unit. The labor and delivery unit policies (available on-line through the intranet) and the partogram flowsheet (paper format only) 3 are strongly aligned with the SOGC clinical practice guidelines. As described in detail here (Kelly et al., 2022), the partogram flowsheet is designed for collection of biophysical data. Data pertain to maternal vital signs, contraction pattern and strength, cervical dilation, fetal heartbeat details, medications, and intravenous therapies. At the same hierarchical level are the CAPWHN (2018)Perinatal Standards which also should influence the unit policies and the partogram flowsheet. A continuous labor support policy exists; however, only one small area on the partogram is designated as space for recording supportive measures and nurses are restricted to using 11 codes.

Practice Setting

Finally, the labor and delivery practice setting is situated at the bottom of the intertextual hierarchy. The unit has instituted particular practices recommended by CPSI, SOGC clinical practice guidelines, and the MOREOB program, all designed to further assist with maintaining patient safety within labor and delivery. These practices include a mandatory continuing education course on fetal health surveillance and interventions aimed at improving inter-professional communication.

Continuing Education

The Provincial Perinatal Program of Newfoundland and Labrador whose mandate is to improve the quality of reproductive care and pregnancy outcomes is housed within this regional health authority. The program is made up various health-care professionals including program managers, pediatricians, clinic nurses, provincial perinatal educator, and nurse educators, to name a few. The provincial perinatal educator is responsible for the promotion and provision of continuing education to all sites that offer obstetrical services within the province. Specifically, the provincial perinatal educator along with the Provincial Perinatal Program, the SOGC fetal health surveillance guidelines (Dore & Ehman, 2020), and the Canadian Association of Perinatal and Women’s Health Nurses (CAPWHN) have all endorsed the Canadian Perinatal Program Coalition’s (2009)Fundamentals of Fetal Health Surveillance educational program as the baseline course for health care professionals working in obstetrics, particularly those working in labor and delivery. Within this regional health authority, the course must be completed every 2 years by labor and delivery nurses, family physicians, obstetrical residents and obstetricians. Details pertaining to this continuing education course are outlined in more detail here (Kelly et al., 2022). The course was made mandatory by the Provincial Perinatal Program due to the lack of consistency with education and interpretation of fetal health surveillance, namely graphic printouts. The provincial perinatal educator informant explains:

We recognize that one of the big problems with fetal health surveillance is consistency of education and consistency of information, it became apparent that everybody was doing something a little different based on the SOGC guidelines. So what we recognized is because the interpretation of graphs is so challenging, one of the first things that we needed to do was to get a consistency of education based on the most current guidelines that we had so that we would try to even the playing field across all [health] regions and all health care professionals.

Inter-Professional Communication

Seventy percent of all preventable harm events experienced by patients are linked to a breakdown in communication (Healthcare Excellence Canada, 2023). In fact, ineffective communication among team members is one of the major contributors to adverse obstetrical events in Canada (Accreditation Canada, Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC), Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA), and Salus Global Corporation, 2016). Therefore, effective communication within interdisciplinary teams is considered to be one of the key elements to ensuring patient safety (Healthcare Excellence Canada, 2023; Lyndon et al., 2011). Besides the MOREOB program which encourages inter-professional team training and learning effective communication skills, this unit has instituted a number of specific communication tools to facilitate successful communication among health care providers including SBAR, Baby Pause, and Safety Huddles.

SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) is a communication tool thought to improve inter-professional communication and patient outcomes (Curtis et al., 2011), and is used by nurses on the unit. The acronym is posted throughout the unit (e.g., on back of staff bathroom doors) and in the birthing rooms for the convenience of nurses. The structure of the reporting tool is designed to standardize how important information is relayed to physicians when an immediate response is required. SBAR is believed to help nurses organize their thoughts and provide a brief, structured, clear, and concise report. This approach, therefore, assists nurses to align their communications style in a manner that is more consistent with that of physicians with the goal to improve inter-professional communication (Hartrick Doane & Varcoe, 2021; Wang et al., 2018).

Baby Pause was created by two nurse educators and is a component of the British Columbia Patient Safety and Learning System that is a web-based tool for health care providers wanting to learn about or report patient safety events, near misses, and hazards. Baby Pause is a patient safety initiative intended to improve patient outcomes and reduce safety events related to fetal health surveillance and the loss of situational awareness (Fraser Health, 2014). Situational awareness is the ability to maintain a “bird’s eye view” of what is going on, to think ahead, and be able to share it with co-workers (Edozien, 2015). The loss of situational awareness can occur when there is stress, or fatigue is high, a lack of understanding as to how to correctly interpret findings, or human error. Baby Pause is meant to reduce loss of situational awareness from happening by having health care providers make a conscious effort to assess fetal well-being, primarily by checking the continuous graphic printout to detect problems early.

Safety Huddles is another communication strategy introduced by the regional health authority. The strategy consists of short meetings of members of the interdisciplinary health care team. Meetings are no more than 10 to 15 min in duration. The aim of Safety Huddles is to proactively enable the health care team to focus on patient safety through team communication and the empowerment of staff to speak up and share patient safety concerns (Health Standards Organization (HSO) & Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI), 2020). Concerns raised during Safety Huddles are then to be directed to the appropriate person or groups for resolution, such as supervisors or patient safety committees (Health Standards Organization (HSO) & Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI), 2020).

Despite the use of these communication tools, researchers like Gergerich et al. (2019) and Paradis et al. (2016) discovered that hierarchies and predetermined ideas about power within health care teams can perpetuate barriers to inter-professional collaboration which impedes communication among team members and, as a result, leads to adverse patient outcomes. Brown et al. (2011) learned how participants in less powerful positions described feeling intimidated and silenced by issues of hierarchy within health care teams. Hierarchies and power imbalances were also evident in our study as described by this health care professional:

So then you get an obstetrician who’s inside, intimidated by a nurse who’s saying, well this is what I see and because the obstetrician may not have that same level of understanding and same level of education, hierarchy sometimes pulls rank and then the nurse gets shut down and the obstetrician says, well this is what we’re going to do. (Health Care Professional Informant)

These findings beg the question as to whether such communication tools actually assist with breaking down hierarchies within health care teams and improve patient (women) outcomes.

Patient Safety Incidents

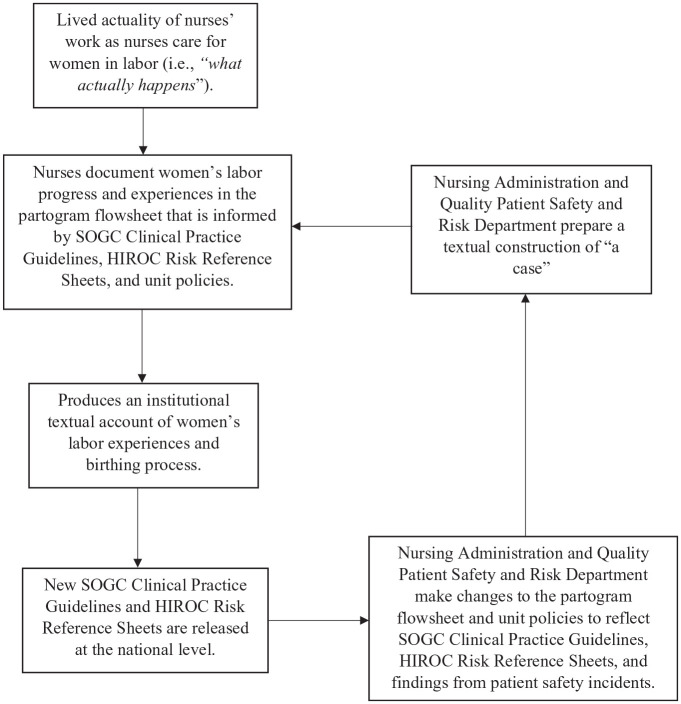

Here, we discuss what happens when patient safety incidents occur in labor and delivery. Specifically, we illustrate how incidents are managed within the regional health authority by way of an ideological circle (i.e., Figure 2). Also graphically depicted is the process by which recommendations following an incident are implemented to prevent similar occurrences from happening in the future.

Figure 2.

Ideological circle.

Note. HIROC = Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada; SOGC = Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Canada.

Patient safety incidents 4 are defined as “an event or circumstance which could have resulted in or did result in unnecessary harm to a patient” (CPSI, 2011, p. 11). There are approximately 380,000 babies born in Canada every year (Statista, 2020) and the majority of births occur safely (Canadian Medical Protective Association [CMPA], 2018), but patient safety incidents within labor and delivery can occur involving the neonate, the mother, or both. Susceptibility to a safety incident is escalated due to the involvement of numerous health care providers from various disciplines, the high acuity, and the unpredictability of events (Murray-Davis et al., 2015). According to HIROC (2015), any suspected injury, harm, or neurological impairment associated with the management of labor, delivery, resuscitation, and, or care during the postpartum period as it relates to the neonate are considered to be adverse neonatal events. The list is extensive and includes conditions such as fetal asphyxia, meconium aspiration pneumonia with suspected poor outcome, shoulder dystocia with short or long-term injury, and errors or omissions contributing to neonatal harm or death. Adverse neonatal events occur in 10% of cases (Kaplan & Ballard, 2012; Pettker, 2011).

Reporting and Review Processes

Patient safety incidents are often complex and involve many contributing factors. Therefore, a hospital reporting system is recommended (CPSI, 2021c). Within the site of our IE study, patient safety incidents are reported through a computerized clinical safety reporting system. One of our study informants explained that “if it’s a 5 or 6 level occurrence which is usually permanent harm or death, it’s usually a multidisciplinary issue. And then I’ll do my review, and the Chief will do their review” (Nurse Manager Informant). Nurses on the labor and delivery unit are expected to report patient safety incidents when they occur (CNA, 2017). Once submitted through the clinical safety reporting system, it becomes textually represented as a case and triggers a series of institutional actions. The case is immediately sent to the Quality Patient Safety and Risk Management Department of the regional health authority and to the nurse manager. When the Risk Management Consultant (who acts as a HIROC liaison) receives notification that an incident has occurred and there is suspected harm to either mother, neonate, or both, the Risk Management Consultant is immediately required to report the incident to the national HIROC representative (HIROC, 2015). “We have an obligation to report that, because why? We have to protect our people and so here is the HIROC piece, right?” (Informant, Risk Management Consultant). Immediate reporting to the regional health authority is vital to enable HIROC representatives to begin an early investigation of the incident while information and details remain fresh in people’s minds (HIROC, 2015). Safety and risk personnel from the regional health authority will begin a review by examining the patient’s chart and by speaking with the nurse(s) involved: “I’ll interview nurses, the manager also speaks to the nurses, and the nurses’ notes [are read and reviewed]” (Informant, Quality and Safety Leader). This is a critical juncture because it is potentially the initial activation of medical-legal discourse by the lawyer and the patient or family, involved.

Once the clinical safety reporting system files the case an internal formal review and detailed examination are initiated. Organizational texts (such as the partogram flowsheet and the progress notes), provide, a supposedly, objective construction of the patient safety incident that is essential in the managerial determination of what occurred, what was done, by whom, and when. The quality assurance personnel, along with the unit nurse manager, MOREOB Quality Improvement Coordinator, the Medical Chief of Obstetrics, and the perinatal provincial educator, review the entire patient chart (including documentation in the partogram flowsheet) to assess the level of care provided by the health care team during the incident. At this point in the review process the team is looking to identify system related issues which involve “anything possible that might have affected the decision-making at the time that might have contributed to the outcome—patient factors, the staff, team decision-making, education, organization policies, standards, and or regulations” (Informant, Quality and Safety Leader).

Nursing and medical care are appraised through reviewing the partogram flowsheet data, continuous electronic fetal monitoring graphic printouts, and narrative progress notes to ascertain a clear understanding of the case. Reviewers rely on the SOGC guidelines, MOREOB education, UpToDate, 5 and organizational and unit policies, as their reference resources. If it is determined there is a violation of the standards of nursing practice, a separate work process begins. The partogram flowsheet and narrative progress notes become a “technology of surveillance” (Rankin & Campbell, 2009, para 31) as explained in the following: “If we feel that there’s a combination of system issues and [individual] accountability issues, the program will take the accountability route and we’ll follow through with the quality route” (Informant, Quality and Safety Leader). The nurse manager notifies the Professional Practice for Nursing Committee of the case. Organizational policies, CRNNL standards of practice, MOREOB recommendations, and SOGC guidelines are consulted. If it is determined that practice is not consistent with the standards, unit policies, or national guidelines, then either the nurse manager or the Professional Practice for Nursing Committee has a duty to report their evidence to the Director of Professional Conduct Review within the provincial nursing regulatory body as a formal complaint (Registered Nurses Act 2008).

If there are no individual accountability issues, the team reunites and compares findings. If discrepancies within the reports are found, the review team will deliberate until consensus is reached: “If we disagree on, which is what most people disagree on, what to call certain decels. And so, we’ll make our case and then we’ll talk it out until we come to an agreement and usually one of us will say, ‘Oh yeah, that totally fits the definition of this’” (Informant, MOREOB Quality Improvement Coordinator). Once the team review is complete the quality assurance department makes specific recommendations at the system level (e.g., new policies and protocols) or proposes changes that are directed at the level of the obstetrical program and labor and delivery unit (e.g., nursing and medical practice, procedures, partogram flowsheet adjustments) to prevent such a reoccurrence.

It should be noted that the foundation of quality improvement is to eliminate a culture of blame within hospitals and, instead, focus on system changes to improve patient safety (Reszel et al., 2019). However, this was not what happened following a patient safety incident a few years prior that all the nurse informants spoke about (Kelly et al., 2022). The nurses observed how two of their nurse colleagues were investigated, reprimanded, and never worked in the unit following the examination. The reviewers determined that both nurses did not provide care reflective of a prudent nurse as outlined by the unit policies, guidelines, and the CRNNL (2019b) Standards of Practice for Nurses and Nurse Practitioners. However, the aim of documentation in health care is to promote patient safety and inter-professional communication (Barry & Kerr, 2019). It appears that this did not occur in this situation. As a result, we discovered nurses are now documenting out of fear, instead of sharing their interventions with other members of the health care team. This means that nurses are over-documenting which is taking their time and focus away from their laboring patients (Kelly et al., 2022). Despite what is supposed to happen during the reporting and review process, health care systems are still very much focused on the individual.

The Ideological Circle

An ideological circle is a textually coordinated, circular process through which institutions “can virtually invent the environment and objects corresponding to its accounting terminologies and practices” (D. E. Smith, 1990b, p. 96). The ideological circle in Figure 2, below, portrays how the intertextual hierarchy (i.e., Figure 1) may be reinvented or reproduced when the labor and delivery unit undergoes internal review following a patient safety incident. The internal review of the patient safety incident requires actualities in subordinate levels of the tertiary care center (i.e., the labor and delivery unit) by way of the patient chart (partogram flowsheet and narrative progress notes) to provide the what, by whom, and when, of the case which signifies translation into an explanatory account that forms the interpreted representation of women’s labor experiences (Yan, 2003). Schematically depicted in Figure 2, is the evolving self-fulfilling circular feedback loop. SOGC’s clinical practice guidelines, HIROC’s safety recommendations in the Risk Reference Sheets, and findings from previous patient safety incidents activate and reinforce ruling relations (i.e., biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses) if the internal reviewers (Nursing Administration and the Quality Patient Safety and Risk Management Department) propose changes to organizational regulations or policies and/or unit policies and procedures.

Organizational texts (unit policies and the partogram flowsheet) are infiltrated by the proposed changes that mediate discursive ruling relations. Unit policies and the partogram flowsheet are amended. New columns are introduced and embedded in the revised partogram flowsheet that is passed on to the provincial perinatal educator for training and implementation by nurses on the labor and delivery unit. The partogram flowsheet is then activated by low-level staff (D. E. Smith, 1990b) as they care for laboring women and the cycle repeats with construction of the institutional textual account of women’s labor and birth experiences.

Similarly, each time new SOGC clinical practice guidelines or HIROC Risk Reference Sheets are updated and released, revised texts are distributed to regional health authorities and to labor and delivery units. The provincial perinatal educator, along with input from the Medical Chief of Obstetrics and the unit nurse manager, activate these revised boss texts by adjusting unit policies and the partogram flowsheet to reflect current recommendations.

Discussion

Nurses think of themselves as members of a caring profession and pride themselves on providing care that is holistic, compassionate, and sensitive to individual patient needs. This is what is believed to distinguish members of the nursing profession from other health care providers (Thorne, 2019; Thorne & Stajduhar, 2017). The Canadian Nurses Association (2015) Framework for the Practice of Registered Nurses in Canada stipulates that holistic care means focusing on the whole person comprised of biophysical, and psychosocial, emotional, social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions. Holistic nursing care facilitates implementation of a patient-centered approach as endorsed by Canadian and provincial nursing standards for practice, for example, the: Canadian Association of Perinatal and Womens Health Nurses [CAPWHN] (CAPWHN, 2018)Perinatal Nursing Standards in Canada, the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN) (2017)Entry-to-Practice Competencies for Nursing Care of the Childbearing Family for Baccalaureate Programs in Nursing, and College for Registered Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador (CRNNL) (2019b) Standards of Practice for Registered Nurses and Nurse Practitioners. However, due to biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses infiltrating the forms and policies that labor and delivery nurses use regularly in their everyday work, nurses are not so much focused on meeting holistic care needs because they must spend an inordinate amount of time and effort on technological interventions (e.g., continuous electronic fetal monitoring) and documentation (Kelly et al., 2022). Other studies found nurses were drawn away from providing labor support and were preoccupied with managing technology (Dobson, 2018) and documentation (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016). Almerud et al. (2008) described similar observations in their investigation of nurses’ work in high acute areas. Advances in technologies in the medical sector, even more than a decade ago within an intensive care unit, had prevented nurses from seeing patients as holistic human beings and impacted the quality of interpersonal relationships with patients. Nurses were observed performing their work in a robotic and detached, technical, skill-driven manner. The same is evident in more recent research studies conducted by Campbell and Rankin (2017), Dean et al. (2015).

While for some, providing supportive measures during labor may sound “soft” and tend to be trivialized in a tertiary care setting of specialized care with focus on biomedical interventions, nurse scholars like Benner (2004) claim such nursing comfort measures are life-giving and valuable in their own right. Providing soothing touch, altering positions, and decreasing stimulation have all been shown to assist with advancing labor progress and the discomforts of labor (Keenan-Lindsay, 2017; Morin & Rivard, 2017). If nurses are task oriented (e.g., focused on the partogram and the acquisition of biophysical data) they may not notice women’s emotional needs which may hinder levels of disclosure, trust, and engagement (Benner, 2004). Similarly, Kitson (2018) documented the importance of fundamental nursing care (i.e., dignity in practice, compassion, patient-centered care) as it provides the physical, psychosocial and relational dimensions to the overall well-being of patients. Kitson notes however, the ongoing valuing of depersonalized mechanistic “task and time” approach to care over meaningful patient engagement is detrimental to meeting patients’ unique caring and safety needs. Not valuing nursing’s personalized, unique, and fundamental role in the provision of health care will have detrimental effects on childbearing women and their families. Experiences women have during childbirth carry physical, psychological, and emotional implications and has been shown to significantly impact women as they assume the mothering role and attempt to bond with their babies (Beck, 2004a, 2004b, 2006; Fenwick et al., 2015; Simkin, 1992; Toohill et al., 2014).

Laboring women are constantly monitored in anticipation for potential development of conditions which may harm the mother, fetus, or both, during the intrapartum period. Nurses are continually documenting biophysical data and biomedical interventions which serve to create an institutional account of labor and the birthing process—endorsed as a biomedical event. When there is a patient safety incident, it is this institutional account, as structured by the boss text (SOGC clinical practice guideline), organizational texts (unit policies, MOREOB education), and the CRNNL Standards for Practice for Registered Nurses and Nurse Practitioners (2019), which, together, are the evidentiary information sought by reviewers to determine whether safe practices and standards of care by health care providers including labor and delivery nurses, were provided. It became apparent to us that any institutional reviews of patient safety incidents rely on biophysical monitoring data as evidence of prudent care leading one to wonder if reviewers are failing to acknowledge and consider the CAPWHN (2018)Perinatal Nursing Standards in Canada that reflect the discourse, principles and values of holistic and supportive practice measures as prudent care of laboring women. By focusing on biomedical indicators of prudent care, are labor and delivery nurses perpetuating the generic evidence-based paradigm (i.e., evidence-based practice) that stems from the evidence-based medicine movement? Recall that Archie Cochrane’s (1972) seminal book Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Services and the Cochrane Library, the Cochrane Collaboration and the Cochrane Criteria, in conjunction with McMaster University’s Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, are responsible for creating a research evidence hierarchy and are the catalysts for the evidence-based medicine movement (Sackett et al., 2000). Clinical knowledge and the evidence base for clinical practice has since shifted (Holmes et al., 2006). “Proponents of evidence-based medicine purport traditional decision making based on intuition, clinical experience and pathophysiologic reasoning alone is substandard; whereas, judgments founded upon scientific research evidence generated from rigorous methods, namely RCTs, are superior to medicine-as-usual” (Porr & Mahtani-Chugani, 2008). We contend that health care providers have since relied on a narrow knowledge base excluding unique patient contexts and experiences (Porter & O’Halloran, 2009), especially in the care of laboring women, and nurses are not able to apply the broader definition of evidence in nursing practice that is depicted in the CRNNL (2019) Standards for Practice.

Findings from our study has shown how childbirth has become a difficult and risky event within the hospital settings. Consequently, nurses are not able to meet the holistic care needs of laboring women as they are under constant pressure that a patient safety incident may occur and could result in legal or professional actions (Kelly et al., 2022). Our findings demonstrate how nurses’ work has become a bio-medically oriented, textually-mediated practice with emphasis on fulfilling the medical-legal risk agenda of the institution which are not consistent with evidence-informed nursing practice.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study was carried out using a critical feminist approach—institutional ethnography, which is a rigorous ethnographic methodology that was strengthened by reflexive practices (reflexive journal, regular committee meetings) and extended immersion in the area (Kelly et al., 2022). Our findings are specific to a precise time and place in which they were produced. We consequently make no claim that our findings are generally applicable in all tertiary care maternity settings within Canada. However, given that both HIROC and the SOGC are national organizations, it reasonable to suspect similar textually mediated social organization of nurses’ work are ongoing within other maternity units across the country.

Conclusion and Recommendations

It is critical that nurses communicate in ways that highlights their unique knowledge, competence, the complexity of their work (Buresh & Gordon, 2006), and the impacts on birth outcomes. SBAR stands for situation, background, assessment, and recommendation, and, is intended as an efficient tool to assist nurses with organizing their thoughts prior to contacting physicians. However, Foronda et al. (2016) highlights how nurses and physicians are taught to communicate differently. On the one hand, nurses are instructed to be descriptive whereas physicians are trained to be succinct. Inter-professional communication experts endorse SBAR for efficiency and clarity to ensure patient safety. The focus of SBAR, however, is restricted mainly to the biophysical dimension of patient care and if used routinely, omitted from this oral communication method is the holistic picture of patients including the psychosocial, emotional, social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions (Johnson et al., 2012) that are unique patient knowledge which nurses know. For instance, significant details of women’s intrapartum experiences are lost or not communicated if SBAR communication becomes the standardized norm on the unit. The threat to nursing practice is mistaking the SBAR tool for everyday use resulting in the routinized, exclusive focus on the biophysical dimension and not on whole person care. By expanding SBAR so that the situation or background include a designated space for nurses to include supportive measures, and other progress notes of pertinence, will create a more holistic picture of laboring women and fetal status. Changes to allow better communication of the nursing practice measures supporting laboring women will result in awareness of the nurse’s role and respect for nursing contributions among physicians and other members of the health care team. Ultimately, altering communication tools like the SBAR will enhance appreciation and the valuing of nurses’ work which we have shown is currently invisible (Kelly et al., 2022) and help to reduce hierarchies and power imbalances within the inter-disciplinary team. Additionally, frequent exposure to the dominant ruling discourses through engagement with organizational texts in their daily work may make it difficult or impossible for nurses to care for laboring women as advocated by the CAPWHN (2018)Perinatal Nursing Standards in Canada. The MOREOB educational sessions as we discussed, are held regularly and all members of the health care team are required to attend. Nurses leading discussions using the CAPWHN (2018)Perinatal Standards to assist with strategizing how nurses in labor and delivery could better apply unique nursing knowledge and skills, in particular, supportive care measures, on a routine basis. These sessions would also facilitate incorporation of nursing knowledge into the MOREOB program and enhance understanding of the nursing role and responsibilities among members of the health care team.

IE offered us a sociological tool for us to deconstruct one of the major unquestioned conditions of nurses’ work practice–the textually mediated social organization. We have reported the extra-local or bigger picture findings in this manuscript and by way of illustration, demonstrated how nurses’ work in labor and delivery is socially organized. As illustrated in the intertextual hierarchy, discursive ruling relations (i.e., biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses) infiltrate boss texts (i.e., SOGC clinical practice guidelines) that inform lower-level organizational documents (e.g., unit policies and the partogram flowsheet), which together, produce an institutional textual account of women’s childbirth experiences. This institutional textual account is vital because it is apparent that this institutionally sanctioned account aligns with an agenda reflective of the biomedical discourse priority of safe care. Nursing documentation must align with institutional imperatives and make known the biomedical assessments and interventions implemented during childbirth. In addition, medical-legal risk discourse also governs the institutional requirements for safeguarding the fetus to mitigate risk and ensure safe care which is achieved through biomedical interventions.

We revealed by way of the ideological circle how biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses are reinforced when new SOGC clinical practice guidelines and HIROC’s safety recommendations are released, for example, following a patient safety incident. When the incident is formally filed, nursing administration and the Quality Patient Safety and Risk Management Department conduct an internal review and recommend revisions to lower-level texts to reflect the current national guidelines. During intrapartum care of women nurses engage the newly revised lower-level texts and the cycle is replicated and the social organization of nurses’ work as portrayed, above, is repeated. We have shown how both biomedical and medical-legal discourses are overshadowing the nursing discourse of holistic care (e.g., hands-on relaxation techniques, position changes, psychosocial and emotional support) and that nurses’ work is socially constituted to reinforce these discursive ruling relations through the texts they routinely use in their labor and delivery work in this tertiary care center.

Nurses work is socially organized to produce well documented evidence of safe care and protect the institution from medical-legal risks at the expense of providing holistic, supportive person and family centered nursing care during childbirth. Nurses need to be aware of their institutional role in the formation of the biomedical and medical-legal risk ideological circle which is tightly woven into a textual process. To break the cycle, nurses must first understand it as we demonstrated in our investigation. IE is an effective tool for nurses to understand, evaluate, and free themselves from ideological control. Such hopeful outlooks is only achievable if nurses can critically understand where they are located in the ideological circle dominated by biomedical and medical-legal risk discourses.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-gqn-10.1177_23333936231170824 for Elucidating the Ruling Relations of Nurses’ Work in Labor and Delivery: An Institutional Ethnography by Paula Kelly, Nicole Snow, Maggie Quance and Caroline Porr in Global Qualitative Nursing Research

Author Biographies

Paula Kelly, RN, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Nursing at Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John’s in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.

Nicole Snow, RN, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Nursing at Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John’s in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.

Maggie Quance, RN, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Caroline Porr, RN, PhD, is a Former Associate Professor in the Faculty of Nursing at Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John’s in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.

While this study occurred, CPSI was a separate organization. Since then, CPSI has amalgamated with Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement to form a new organization known as HealthCare Excellence Canada.

A specialty consulting and implementation firm that assists health care organizations improve performance and quality outcomes through increased inter-professional collaboration.

During this study, the partogram flowsheet and other patient chart documents were available in paper format only. However since then, there is a plan for the regional health authority to convert all documentation in the labor and birth unit to electronic documentation.

Patient safety incidents are now referred to as: 1. Harmful incident. A patient safety incident that resulted in harm to the patient. Replaces “adverse event,” “sentinel event,” and “critical incident.” 2. No-harm incident: A patient safety incident that reached a patient but no discernible harm resulted. 3. Near miss: A patient safety incident that did not reach the patient. Replaces “close call.”

UpToDate is an online database used for clinical resources.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported from Newfoundland and Labrador Support for People & Patient Oriented Research & Trials, College of Registered Nurses for Newfoundland & Labrador & Canadian Nurses Foundation.

ORCID iD: Paula Kelly  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5457-5331

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5457-5331

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Accreditation Canada, Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC), Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA), and Salus Global Corporation. (2016). Obstetrics services in. Advancing Quality and Strengthening Safety. https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/static-assets/pdf/research-and-policy/system-and-practice-improvement/Obstetrics_Joint_Report-e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Almerud S., Alapack R. J., Fridlund B., Ekebergh M. (2008). Caught in an artificial split: A phenomenological study of being a caregiver in the technologically intense environment. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 24(2), 130–136. 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbrenner A. P., Hanson L., Johnson T. S., Kelber S. T. (2016). Nurses’ own birth experiences influence labor support attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 45(4), 491–501. 10.1016/j.jogn.2016.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry M. A., Kerr N. (2019). Documenting and reporting. In otter P., Stockert P., Perry P., Hall A. G., Astle A., Duggleby, W. B. J. (Eds.), Canadian fundamentals of nursing (6th ed., pp. 233–253). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Beck C. T. (2004. a). Birth trauma: In the eye of the beholder. Nursing Research, 53(1), 28–35. 10.1097/00006199-200401000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck C. T. (2004. b). Post-traumatic stress disorder due to childbirth: The aftermath. Nursing Research, 53(4), 216–224. 10.1097/00006199-200407000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck C. T. (2006). The anniversary of birth trauma: Failure to rescue. Nursing Research, 55(6), 381–390. 10.1097/00006199-200611000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P. (2000). The roles of embodiment, emotion and lifeworld for rationality and agency in nursing practice. Nursing Philosophy, 1(1), 5–19. 10.1046/j.1466-769x.2000.00014.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P. (2004). Relational ethics of comfort, touch, and solace-endangered arts? American Journal of Critical Care, 13(4), 346–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaillon L. (2012). An analytic glossary to social inquiry using institutional and political activist ethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(5), 607–627. 10.1177/160940691201100506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bisits A. (2016). Risk in obstetrics - Perspectives and reflections. Midwifery, 38, 12–13. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake J., Green C. R. (2019). SOGC clinical practice guidelines: A brief history. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 41(S2), S194–S196. 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohren M. A., Hofmeyr G. J., Sakala C., Fukuzawa R. K., Cuthbert A. (2017). Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7(7), CD003766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J., Lewis L., Ellis K., Stewart M., Freeman T. R., Kasperski M. J. (2011). Conflict on interprofessional primary health care teams–can it be resolved? Journal of Interprofessional Care, 25(1), 4–10. 10.3109/13561820.2010.497750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buresh B., Gordon S. (2006). From silence to voice: What nurses know and must communicate to the public (2nd ed.). ILR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M., Gregor F. (2008). Mapping social relations: A primer in doing institutional ethnography. Higher Education University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. L. (1998). Institutional ethnography and experience as data. Qualitative Sociology, 21(1), 55–73. 10.1023/a:1022171325924 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. L., Rankin J. M. (2017). Nurses and electronic health records in a Canadian hospital: Examining the social organisation and programmed use of digitised nursing knowledge. Sociology of Health & Illness, 39(3), 365–379. 10.1111/1467-9566.12489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Perinatal and Women’s Health (CAPWHN). (2018). Perinatal nursing standards in Canada. https://capwhn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/PERINATAL_NURSING_STANDARDS_IN_CANADA.pdf

- Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN). (2017). Entry-to-practice competencies for nursing care of the childbearing family for baccalaureate programs in nursing. https://www.casn.ca/2018/01/entry-practice-competencies-nursing-care-childbearing-family-baccalaureate-programs-nursing/

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). (2020). Top 5 reasons for hospital stays in Canada. https://www.cihi.ca/en/hospital-stays-in-canada

- Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA). (2018). HIROC, SOGC, and CMPA join forces as partners in Salus Global. https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/static-assets/pdf/connect/18_salus_global_backgrounder-e.pdf

- Canadian Nurses Association. (2017). Code of ethics for registered nurses. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/code-of-ethics-2017-edition-secure-interactive [PubMed]

- Canadian Nurses Association (CNA). (2021). Certification nursing practice specialties. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/certification/get-certified/certification-nursing-practice-specialties

- Canadian Nurses Protective Society (CNPS). (1999). Legal risks in nursing. InfoLAW, 8(1). https://cnps.ca/article/legal-risks-in-nursing/ [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nurses Protective Society (CNPS). (2002). Obstetrical nursing. InfoLAW, 11(1). https://cnps.ca/article/obstetrical-nursing/ [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nurses Protective Society (CNPS). (2004). Negligence. InfoLAW, 3(1). https://cnps.ca/article/negligence/ [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nurses Protective Society (CNPS). (2007). Malpractice lawsuits. InfoLAW, 7(2). https://cnps.ca/article/malpractice-lawsuits/ [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nurses Protective Society (CNPS). (2020). Quality documentation: Your best defense. InfoLaw, 1(1). https://cnps.ca/article/infolaw-qualitydocumentation/ [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI). (2011). Disclosure Working Group: Canadian disclosure guidelines: Being open and honest with patients and families. https://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/en/toolsResources/disclosure/Documents/CPSI%20Canadian%20Disclosure%20Guidelines.pdf