Abstract

Objective:

To examine the reliability of the Disruptive Behavior Diagnostic Observation Schedule (DB-DOS), a new observational method for assessing preschool disruptive behavior.

Method:

The DB-DOS is a structured clinic-based assessment designed to elicit clinically salient behaviors relevant to the diagnosis of disruptive behavior in preschoolers. Child behavior is assessed in three interactional contexts that vary by partner (parent versus examiner) and level of support provided. Twenty-one disruptive behaviors are coded within two domains: problems in Behavioral Regulation and problems in Anger Modulation. A total of 364 referred and nonreferred preschoolers participated: interrater reliability and internal consistency were assessed on a primary sample (n = 335) and test-retest reliability was assessed in a separate sample (n = 29).

Results:

The DB-DOS demonstrated good interrater and test-retest reliability. Confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated an excellent fit of the DB-DOS multidomain model of disruptive behavior.

Conclusions:

The DB-DOS is a reliable observational tool for clinic-based assessment of preschool disruptive behavior. This standardized assessment method holds promise for advancing developmentally sensitive characterization of preschool psychopathology.

Keywords: disruptive behavior, diagnostic observation, developmental psychopathology, preschool behavior problems

During the past decade, multiple, independent studies have demonstrated that DSM-based disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs; i.e., oppositional and conduct disorders) can be identified in preschool children.1-4 Because these studies broke new ground applying psychopathological nosology to early childhood, by necessity they required hypothesis testing without developmentally validated tools.5 Even with this methodological constraint, there is now clear and consistent evidence that the broad constellation of behaviors that comprise DBDs are present and impairing, and occur at rates in young children comparable to those in older children.1-4,6,7 Although initial studies relied on parent interviews originally designed for school-age children, similar results have recently been reported in studies using interviews specifically developed for the preschool period.7-9

Although these newly developed parent-report diagnostic interviews have advanced identification of preschool psychopathology, the limitations of sole reliance on parents as informants10 are amplified during the preschool period because young children cannot serve as informants about their own behavior. In addition, interview-based methods can only tap constructs identified a priori, which “constitutes a serious constraint in the discovery of clinically relevant phenomena not already recognized.”11 This level of specification is increasingly essential for the more precise phenotypic description required for hypothesis testing in neuroscientific, genetic, and other etiological investigations designed to identify causal mechanisms in the development of psychopathology.11,12 Finally, identifying a behavior as clinically significant during the preschool period requires sophisticated and developmentally informed distinctions.13

Diagnostic observation provides a standardized method that serves as an additional informant about child behavior in conjunction with parent interviews and also generates essential information for phenotypic characterization. As a case in point, diagnostic observation has played a critical role in establishing the developmental validity and phenotype of another early childhood disorder, autism.14 Direct observation of young children’s behavior has long been considered central to developmentally sensitive assessment of young children and the study of preschool behavior problems.15-17 This is because observational paradigms provide information about child behavior within the family context while also providing a relatively naturalistic way in which to capture child behavior patterns within a laboratory setting. Many studies of preschool behavior problems have incorporated observational assessments of parent–child interaction.18-20 However, because these paradigms were not designed to be diagnostically informative, they are of limited clinical utility.21,22 In contrast, examiner-based assessments are designed to be clinically sensitive by standardizing adult responses in a manner that presses for a range of clinically salient behaviors in the child, but as a result they lack the ecological validity of parent-child assessment. Thus, combining examiner- and parent-based behavioral observation paradigms provides complementary methods for incorporating the interactive nature of social behavior into the assessment of clinical significance.

To this end, we developed the Disruptive Behavior Diagnostic Observation Schedule (DB-DOS).23 We first identified salient behaviors and dimensions of behavior based on DSM-IV DBD nosology,24 developmental research,25-28 and clinical experience.29 A central aspect of this process was defining clinical patterns in this age period in a manner that distinguished them from the normative misbehaviors of early childhood.30 This led to a conceptualization of two core domains of disruptive behavior across developmental periods: (1) Problems in Behavioral Regulation: A defining characteristic of DBDs is a failure to regulate behavior in keeping with social rules and norms. This latent construct encompasses a range of DBD symptoms reflecting a resistant, inflexible style in response to environmental demands (e.g., argumentativeness), blatant disregard of rules (e.g., curfew violation), and failure to use adaptive social problem-solving strategies (e.g., often starts fights). To operationalize problems in Behavioral Regulation in a developmentally sensitive manner, a range of DB-DOS codes were developed to enable systematic observation of clinically concerning manifestations in young children (e.g., stubborn defiance, deliberate destructiveness, behavioral inflexibility). (2) Problems in Anger Modulation: A second defining characteristic of DBDs reflect anger dyscontrol. This latent construct incorporates DBD symptoms reflecting irritable, sullen mood (e.g., angry/resentful) and dysregulated expressions of anger (e.g., often loses temper). On the DB-DOS, a range of codes were developed to capture observable manifestations of problems in Anger Modulation in young children (e.g., intensity, poor coping with frustration). (See Appendix for list of items in each DB-DOS domain).

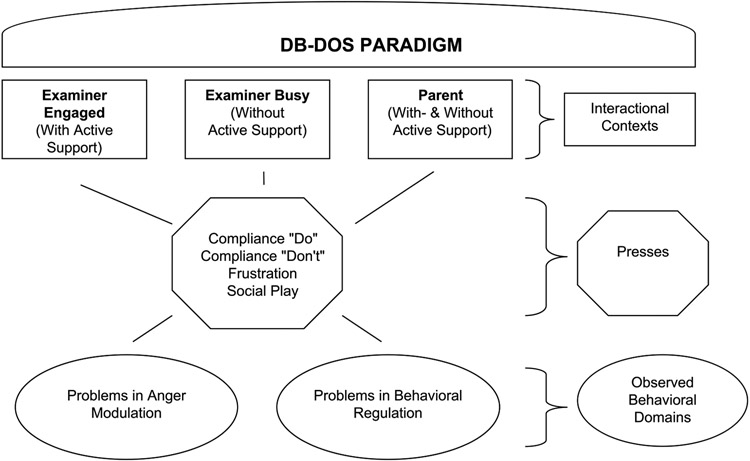

In developing the structure of the DB-DOS, we drew on both developmental and diagnostic observation traditions. In recognition of the importance of an observational structure that integrates context into standardized assessment of child behavior, the DB-DOS paradigm is composed of three interactional contexts that vary by partner and demand characteristics. As Figure 1 illustrates, each interactional context includes parallel sets of presses designed to elicit a range of clinically salient behaviors. The examiner contexts provide an opportunity to assess child disruptive behavior in a manner that is comparable across examiners by applying a set of guidelines for examiner responses to child disruptive behavior. This examiner response hierarchy is designed to allow the full range of clinically salient behavior to unfold while ensuring that the behavior does not escalate unduly. In addition, the inclusion of two separate examiner contexts (Examiner Engaged and Examiner Busy) enables assessment of the child’s ability to regulate emotions and behavior across contexts that systematically vary in terms of the level of support provided to the child. The parent context enables assessment of child behavior within the parent–-child relationship. Examination of patterns of behavior across these three DB-DOS interactional contexts enables assessment of the pervasiveness of child disruptive behavior.

Fig. 1.

Disruptive Behavior Diagnostic Observation Schedule (DB-DOS) schematic. In an earlier conceptual article introducing the DB-DOS,23 we referred to the problems in behavioral regulation domain as the disruptive behavior domain and to the problems in anger modulation domain as the modulation of negative affect domain, and we referred to the DB-DOS interactional contexts as modules.

The DB-DOS coding system was specially designed to distinguish the normative misbehavior of the preschool period from clinically concerning behavior3 via an emphasis on behavioral quality. For example, the DSM-IV oppositional defiant disorder symptom “often actively defies or refuses to comply” is measured observationally on the DB-DOS via multiple types of noncompliance common in young children (i.e., defiance, passive noncompliance, and rule breaking with and without supervision).27 Similarly the oppositional defiant disorder symptom “often loses temper” is captured on the DB-DOS in terms of multiple codes assessing quality of anger modulation (e.g., difficulty recovering, ease of elicitation). DB-DOS codes are global, integrated judgments that parallel typical clinical observation rather than frequency counts of discrete behaviors.

We have previously reported preliminary evidence that individual behaviors coded on the DB-DOS discriminate normative misbehavior from disruptive behavior in preschool children.30 In the present study, we examine the psychometric reliability of the DB-DOS in a behaviorally heterogeneous sample of 3- to 5-year-old children.

METHOD

Participants

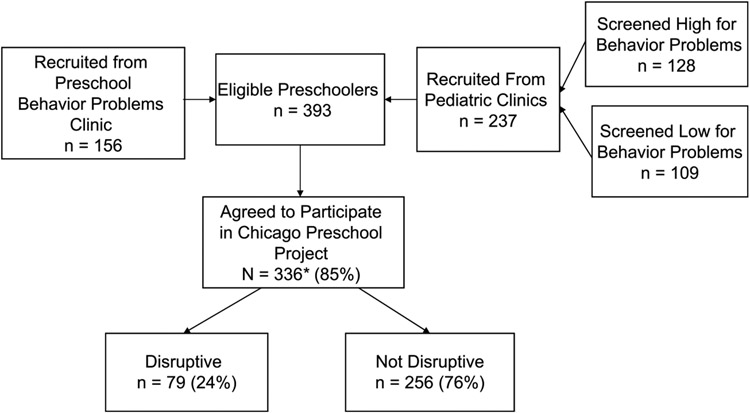

Two samples were recruited for the reliability study (primary reliability and test-retest). Samples were recruited from clinics affiliated with two Midwestern U.S. universities serving predominantly urban, disadvantaged populations. Inclusion criteria included age between 3 and 5 years, residence with biological mother, attendance in out-of-home day care or school, and low income. Children were excluded if they had a serious developmental disability or medical condition. Because a primary goal in developing the DB-DOS was to generate parameters that would inform the distinction between typical and atypical behavior, our sampling strategy was to recruit children along the full behavioral spectrum. Thus, we recruited clinically referred children and nonreferred children with and without behavioral concerns. Referred children were recruited from a specialty clinic for preschool behavior problems and nonreferred children were recruited from pediatric and family practice clinics (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Study flowchart. *One child was excluded from reliability analysis because he did not complete the Disruptive Behavior Diagnostic Observation Schedule (analytic sample = 335). Disruptive behavior status is based on parent and/or teacher report of symptoms and impairment.

Primary Reliability Sample.

A total of 336 mother-child dyads were recruited. Referred (n = 123) and nonreferred children without behavioral concerns (n = 100) were originally recruited for a case-control study of the validity of DBDs in preschool children.9 To ensure sufficient power and behavioral heterogeneity for this DB-DOS validation study, we recruited an additional 11 referred children and a subgroup of nonreferred children with behavioral concerns (n = 102), resulting in a total sample of 336 (Fig. 2). One child was excluded because there were no DB-DOS data for him; thus, the analytic sample for this reliability study is 335.

Referred children.

Forty percent (n = 134) of the sample was recruited from consecutive referrals to a preschool behavior problems clinic. Of the 156 eligible referred children, 86% (n = 134) agreed to participate, 9% (14) could not be scheduled, and 5% (8) refused.

Nonreferred children with behavioral concerns.

Thirty percent (n = 102) of the sample was composed of children identified as nonreferred with behavioral concerns. Behavioral eligibility was established via a screening procedure developed for this study based on (1) report of parent or teacher or other adult concern about child behavior and/or frequent aggression, noncompliance, and/or tantrums and (2) the child had not received, nor was the family seeking, an evaluation for behavior problems. Ninety-eight percent (n = 2,910) of the 2,970 mothers approached in the pediatric and family practice clinics agreed to participate in the screening. Of these, 20% (n = 576) met basic demographic eligibility for the study. From this pool, 22% (n = 128) were behaviorally eligible based on the screen. Eighty percent (n = 102) of this group agreed to participate, 16% (21) could not be scheduled, and 4% (5) refused.

Nonreferred children without behavioral concerns.

The final 30% (n = 100) of the sample was composed of nonreferred children without behavioral concerns. Caregivers responded to fliers posted in waiting rooms of the pediatric and family practice clinics. Eligibility for this group was based on a telephone screen determining that there were no concerns about the child’s behavior and that the parent was not seeking an evaluation: 92% (n = 100) agreed to participate, 7% (n = 8) could not be scheduled, and 1% (n = 1) refused.

Eighty-four percent of the children were African American, 8% were white, 3% were Hispanic, 2% were multiracial, and the remaining 3% were identified as other. Twenty-two percent of the mothers were married, with an average annual income of $21,743 (SD $16,544). The majority of mothers (87%) had completed high school. Forty-five percent of the children were female. Child age was distributed as follows: 35.5% (n = 119) were 3-year-olds, 32.2% (n = 108) were 4-year-olds, and 32.2% (n = 108) were 5-year-olds (mean 53.6 months, SD 10.1). Child race, sex, and age did not differ by recruitment source. Twenty-four percent (n = 79) of the preschoolers were identified as having a DBD based on parent and/or teacher report of DBD symptoms and impairment (for details, see Part II, Validity).

DB-DOS Test-Retest Sample.

A separate sample was recruited to examine test-retest reliability of the DB-DOS. Recruitment procedures were identical to those described above. Fifty-nine percent (n = 17) of these preschoolers were referred for behavior problems, 10% (n = 3) were nonreferred children with behavioral concerns, and 31% (n = 9) were nonreferred without behavioral concerns.

Method

Sociodemographic Information.

Mothers provided sociodemographic information in a background interview including age, sex, and ethnicity.

DB-DOS.

The DB-DOS is a 50-minute structured laboratory observation that is divided into three interactional contexts: one parent context and two examiner contexts. Types of tasks are parallel across the three contexts, including compliance “do” and “don’t,”31 frustration, and social play tasks. In the examiner contexts, support is varied at the context level. In the Examiner-Engaged context, the examiner is actively engaged with the child, whereas in the Examiner-Busy context, the examiner is present but busy with his or her own work. In addition, the examiner also briefly leaves the room to press for potential covert rule-breaking behaviors during the Examiner-Busy context. In the Parent context, support is varied at the task level. Specifically, several tasks are designed for active parent engagement and one task is a withdrawal-of-attention task in which the parent instructs the child to work independently (i.e., read a book) while the parent is busy completing a questionnaire. Procedures are explained to the parent before starting the tasks and parents are provided with simply worded instructions on flip cards, with transitions between tasks being marked by the ringing of a bell.

The DB-DOS coding system consists of 21 codes organized in terms of problems in the domains of Behavioral Regulation and Anger Modulation. Distinctions between normative misbehavior and disruptive behavior are made within the DB-DOS coding system by defining qualitative breakpoints that mark the shift from typical to atypical. Ordinal ratings are made along a continuum: normative variation (0 = normative behavior; 1 = normative misbehavior) and clinically concerning (2 = of concern, 3 = atypical). Scoring yields domain scores for each context (e.g., Behavioral Regulation in the Examiner-Engaged context) that are calculated as sums as well as composite domain scores that are calculated as total scores across all three contexts. Thus, the DB-DOS yields six scores (two domains × three contexts).

DB-DOS Administration.

Nonclinician research assistants were trained on DB-DOS administration by two of the coauthors who are licensed clinical psychologists with expertise in preschool disruptive behavior.29 Training included review of the DB-DOS manual, live and videotaped observations of the DB-DOS, and practice administrations. Examiners were considered reliable in DB-DOS administration after achieving fidelity on at least two administrations based on direct observation of fidelity by one of the coauthors. Fidelity assessment was measured with a structured checklist that evaluated whether the examiner demonstrated comfort and familiarity with task procedures, was naturally and appropriately responsive to child social bids, and implemented the response hierarchy for responding to child disruptive behavior in a well-paced and flexible manner. Examiners were blind to referral status, and ongoing monitoring of fidelity of administration occurred via weekly videotaped reviews. Order of interactional contexts was standard for all administrations: Parent, Examiner Engaged, and Examiner Busy.

DB-DOS Coding.

An independent team of coders was trained by one of two criterion coders (two of the coauthors). Coders were blind to child clinical status. Coding was completed via videotaped review. Behaviors were coded separately for each DB-DOS context. Initial reliability was established via 80% exact item-level agreement with one of the criterion coders. Approximately 23% (n = 240) of the contexts were randomly selected for double-coding to monitor ongoing interrater reliability.

Procedures.

Informed consent was obtained from the mothers before the laboratory visit. All of the procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at both universities. Mothers completed a diagnostic interview while the child was administered developmental testing. The mothers and children then participated in the DB-DOS. For participants in the test-retest subsample, the mothers and children returned to complete a second DB-DOS approximately 4 weeks after the baseline assessment (mean 29 days, SD 2, range 25–35).

Internal consistency was examined with Cronbach α.32 Item-level interrater reliability was calculated within context, using weighted κ values (to take differences in degree of agreement into account) and the percentage of exact agreement. Mean weighted κ values >.40 were considered adequate with κ values >.60 treated as substantial.33-35 Test-retest reliability and interrater agreement at the domain level were assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients.36,37 We also examined mean level differences in domain scores at test and retest. Finally, confirmatory factor analyses were used to test the fit of the multidomain model using Mplus version 4.21 and robust maximum likelihood estimation due to skewness of the measures.

RESULTS

Item-Level Interrater Reliability

Diagnostic observation measures may include clinically salient items whose occurrence is too low to be evaluated statistically.38 Five items (all in the Behavioral Regulation domain) were rated as present fewer than six times. These items were verbal aggression (two items), directed aggression, spiteful behavior, and sneaky behavior. Because estimates of reliability can be unduly biased by differences between a single pair of raters for items with very low base rates, these items were excluded from item-level interrater reliability analyses for any context in which the base rate was less than six. They were also excluded from domain-level analyses, although they were retained for future use as potentially important indicators of clinical significance.

Overall, item-level interrater reliability was good (overall mean κ = .68; mean weighted κ by domain ranged from .64 to .71). Item-level weighted κ values ranged from .44 to .91, with >80% in the substantial range (Table 1). Interrater reliability was adequate in all contexts. Finally, despite expected variation across coders, the overall pattern of disagreement suggested that this was not of substantial clinical significance. Of greatest clinical significance are differences between scores of 0 (clearly normative) and 3 (clearly atypical) because they represent the maximal possible interrater disagreement. There were no 0/3 differences between raters.

TABLE 1.

Item-Level Interrater Reliability

| Domain | Examiner Engaged |

Examiner Busy |

Parent |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted κ | % Exact Agreement |

Weighted κ | % Exact Agreement |

Weighted κ | % Exact Agreement |

|

| Behavioral Regulation | ||||||

| Mean | .71 | 82% | .82 | 84% | .60 | 74% |

| Range | .61–.77 | 72%–93% | .73–.91 | 69%–96% | .44–.76 | 57%–94% |

| Anger Modulation | ||||||

| Mean | .62 | 84% | .68 | 79% | .62 | 71% |

| Range | .46–.75 | 73%–93% | .59–.71 | 72%–88% | .44–.68 | 66%–75% |

Domain-Level Reliability

Internal Consistency.

Overall, the two domains exhibited good internal consistency (Table 2), both in terms of total domain scores (mean 0.88, range 0.84–0.92) and by context (range 0.82–0.93).39 Internal consistency did not differ by child age or sex. Interrater reliability for domain scores was also excellent across the contexts (intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.87 to 0.97; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Domain Score Reliability

| Domain | Cronbach α | Item Loadingsa | Interrater ICC | Test-Retest ICC | Test Mean (SD) | Retest Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Regulation | Mean .84 | Mean 0.95 | Mean 0.70 | 5.31 (4.47) | 4.57 (5.23) | |

| Examiner Engaged | .88 | .57–.86 | 0.95 | 0.71 | 4.21 (3.86) | 3.89 (4.65) |

| Examiner Busy | .82 | .29–.72 | 0.97 | 0.78 | 4.48 (5.12) | 4.21 (5.94) |

| Parent | .82 | .37–.77 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 7.24 (4.44) | 5.62 (5.11) |

| Anger Modulation | Mean .92 | Mean 0.89 | Mean 0.77 | 4.38 (4.74) | 3.58 (4.59) | |

| Examiner Engaged | .90 | .50–.84 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 2.93 (3.45) | 2.61 (3.94) |

| Examiner Busy | .93 | .66–.85 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 4.59 (5.08) | 3.51 (5.03) |

| Parent | .93 | .67–.85 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 5.62 (5.17) | 4.62 (4.81) |

Note: Differences between test and retest domain scores were nonsignificant (t ranged from 0.05 to 1.29; all p values > .05). ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

One item loaded below 0.3 in one of the DB-DOS contexts. To ensure cross-context consistency, this item was retained for domain scores in all three contexts.

Test-Retest Reliability of Domain Scores.

Test-retest analyses indicated good reliability across domains and contexts (Table 2; intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.61 to 0.85). Across the contexts, domain scores tended to decrease slightly in the second testing; however, none of the changes in domain scores from test to retest were significant.

Domain Intercorrelations Across Contexts.

Pearson correlations among the DB-DOS domains across contexts indicated modest to substantial consistency in child behavior across the different DB-DOS contexts (Table 3). Fisher r to z transformations indicated that cross-context associations within a domain were significantly higher across the two examiner contexts (r ranged from 0.43 to 0.59) relative to associations between each of the examiner contexts and the parent context (r ranged from 0.12 to 0.29).

TABLE 3.

Domain Intercorrelations Across Contexts

| Examiner Busy | Parent | |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Regulation | ||

| Examiner Engaged | 0.59** | 0.29** |

| Examiner Busy | 0.22** | |

| Anger Modulation | ||

| Examiner Engaged | 0.43** | 0.12** |

| Examiner Busy | 0.21** |

p < .01.

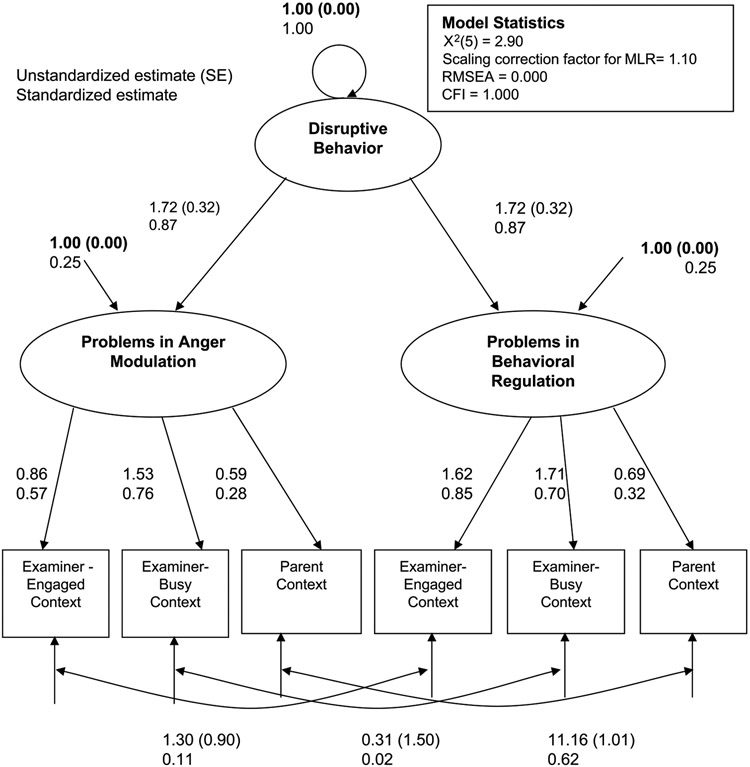

Factor Structure.

To test the fit of our multidomain model of disruptive behavior, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis. A higher order confirmatory factor analysis was fitted for the latent disruptive behavior construct with two second-order factors, Anger Modulation and Behavioral Regulation. Each second-order factor had three indicators (for a total of six observed indicators) that reflected scores for the two domains within each of the three interactional contexts. The six observed measures are the sums of the ordinal items listed in the Appendix. To obtain the latent disruptive behavior factor, loadings of the two second-order factors onto the disruptive behavior factor were constrained to be equal. Error correlations among indicators from the same context were estimated. The results of the final confirmatory factor analytic model are shown in Figure 3. Model fit was excellent (χ2 = 2.5, comparative fit index [CFI] = 1.000, root mean square error approximation = 0.0000). Results of a scaled robust maximum likelihood χ2 difference test40 revealed a significant increase in overall model fit with the multidomain model compared to the unidimensional model (robust maximum likelihood χ2 = 89.8, p < .001).

Fig. 3.

Disruptive Behavior Diagnostic Observation Schedule (DB-DOS) factor structure. MLR = robust maximum likelihood; RMSEA = root mean square error approximation; CFI = comparative fit index.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that a relatively brief, laboratory-based diagnostic observation yields reliable information about patterns of disruptive behavior in young children. Establishing the reliability of the DB-DOS is the first step in the validation process (see Part II for a report on the validity of the DB-DOS). The promise of the DB-DOS for advancing the science and practice of preschool mental health is substantial. Disruptive behavior problems are the most common reasons for mental health referral of young children, but distinguishing them from the normative misbehaviors of early childhood is challenging for clinicians, particularly during a relatively brief assessment in which the clinically relevant behaviors may or may not be observed. The DB-DOS uses presses to increase the range of behaviors typically observed within the clinic and also provides a systematic method for codifying clinical observations. By providing a standard metric with which independent clinicians can directly assess preschool disruptive behavior, the DB-DOS may serve as the basis for a discourse that will generate a more nuanced and systematic understanding of clinical distinctions in young children.

The reliable identification of variations in child behavior across parent and examiner contexts is promising for assessment of clinically salient aspects of young children’s disruptive behavior in context. In addition, the parent context provides essential data on individual differences in parenting behavior via a companion system for coding parental behavior.41 A standardized clinical tool that assesses child and parent behavior in concert is of particular salience in the assessment of disruptive behavior because problematic parenting has been implicated in its early emergence.42

Correlations between domain scores across interactional contexts were relatively modest. As would be expected, correlations were significantly stronger for behavior occurring with the same interactional partner (i.e., behavior within the examiner contexts). This is consistent with the findings of others who have compared behavioral observations of young children across multiple interactional contexts.43 Thus, it is particularly striking that the DB-DOS multidomain model of disruptive behavior that incorporated ratings of behavior across interactional contexts demonstrated exceptional fit and was a better fit than a unitary model of disruptive behavior. Unlike DSM-IV criteria for childhood disorders such as autism or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder that specify symptoms in terms of core domains, DSM-IV DBD nosology is a descriptive list of interchangeable symptoms that does not take such patterns into account. Determining the clinical and prognostic significance of assessing disruptive behavior across multiple domains and interactional contexts will be an important component of future research.

Our extensive clinical experience with disruptive preschoolers is a cornerstone of the DB-DOS.29 From this clinical experience, we derived the critical importance of capturing the heterogeneous manifestations of disruptive behavior in young children and the need for nuanced observations to distinguish it from the normative misbehavior of early childhood. This clinical knowledge also underlies the emphasis of the DB-DOS on the quality of behavior and its pervasiveness. The varying structure of the two DB-DOS examiner contexts is further designed to parallel the typical clinician’s systematic use of the self in assessing the child’s capacity for regulation, both independently and in response to environmental scaffolding.

The DB-DOS was designed to be a brief, clinic-based measure using simple, easily available materials. This was done with the goal of ensuring its clinical feasibility for use as a direct assessment tool to inform diagnostic and treatment decisions. Structured clinical observations have demonstrated incremental utility for both enhancing diagnostic validity14 and predicting treatment outcome.44 The ultimate goal of the DB-DOS is to provide an instrument that can be widely used in both research and practice. Establishing research reliability is a critical foundation for clinical validation. Findings reported here are on the research reliability of the DB-DOS as administered by trained research assistants and coded by an independent research coding team. Demonstrating clinical utility will require that administration and coding are bundled so that the DB-DOS is administered and scored in real time by the clinician, interrater and test-retest reliability of this realtime coding is demonstrated, and diverse clinicians with a range of experience can be trained to administer the DB-DOS reliably. However, we note that the DB-DOS is not intended to train individuals how to do clinical observation, but rather to provide trained observers with a standard method of clinical observation.23 Thus, we anticipate that experience in clinical observation and assessment of young children will be a prerequisite for its use.

For this initial measurement validation study, we used a sampling strategy that would maximize behavioral heterogeneity, including referred preschoolers at the more severe end of the disruptive behavior spectrum. Because this study was originally designed to identify patterns of disruptive behavior in children growing up in low-income environments, the sample is also predominantly low income and African American. Replication of these findings in representative samples will be an important next step.

Diagnostic observation has much to contribute to identification and characterization of preschool psychopathology but it also has limitations. Because it does not assess the history of behavior, it is intended as a complement to parent interviews. In addition, as evident from the low base rates of aggressive behaviors on the DB-DOS, the brief nature of diagnostic observation makes it less than optimal for assessing clinically important but more episodic behaviors. Observing such behaviors on the DB-DOS is informative, but their absence cannot be interpreted as the absence of a Symptom.38.

Establishing the reliability of a diagnostic observation specifically designed to distinguish the normative misbehavior of early childhood from clinical symptoms represents important progress toward developmentally sensitive characterization of preschool disruptive behavior. Demonstrating the validity of the DB-DOS and developing approaches for combining clinical information across diagnostic observation and interview methods are essential next steps for making this a clinically useful tool. The generation of a standardized set of developmentally validated tools via this process will enable the application of the gold standard multimethod, multiinformant approach to the assessment of preschool children. By providing a common metric for clinical evaluation of young children, we can enhance accurate identification during the crucial period for early intervention and prevention of these common mental health problems.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National of Institute of Mental Health grants R01 MH68455 and MH62437, National 0–3, and the Walden and Jean Young Shaw and Children’s Brain Research Foundations.

APPENDIX: DB-DOS ITEMS BY DOMAIN

Behavioral Regulation Domain

Defiance

Passive noncompliance

Predominance of noncompliance

4–5. Rule breaking (coded in all contexts; in examiner contexts, rule-breaking that occurred with and without supervision was coded separately)

6–7. Lack of admission of rule-breaking (coded only in examiner contexts with separate codes for rule-breaking that occurred with and without supervision)

Provocative behavior

Behavioral inflexibility

Destructiveness

Directed aggression*

12–13. Verbal aggression* (coded separately for threats and cursing)

Spiteful behavior*

Sneaky behavior*

Anger Modulation Domain

Intensity of irritable/angry behavior

Predominance of irritable/angry behavior

Ease of elicitation of irritable/angry behavior

Rapid escalation of irritable/angry behavior

Difficulty recovering from irritable/angry episodes

Copes with frustration poorly

*Denotes low-frequency items that were omitted from factor analysis.

Footnotes

This work has been importantly shaped by ongoing critical discussions with our colleagues Patrick Tolan, Daniel Pine, Edwin Cook Jr, Catherine Lord, Kimberly Espy, David Henry, Nathan Fox, and Chaya Roth, and our students Anil Chacko, Nicole Bush, and Melanie Dirks. We thank Drs. Janis Mendolsohn and Saul Weiner for facilitation of pediatric recruitment. The DB-DOS is dedicated to the memory of beloved student and colleague Kathleen Kennedy Martin.

Disclosure: Dr. Leventhal is an advisor/consultant to the Children’s Brain Research Foundation, Eli Lilly, and Janssen; is on the speakers’ bureaus of Bristol-Myers Squibb and Janssen; and has received research funding from Abbott, BMS, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, McNeil Pediatrics, Forest, NIH, NICHD, NIDA, NCI, Pfizer, and Shire. Drs. Briggs-Gowan and Carter receive royalties from Harcourt Assessment for the ITSEA/BITSEA measures they developed. Dr. Cicchetti receives royalties from the Vineland measure. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

LAUREN S. WAKSCHLAG, Institute for Juvenile Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

CARRI HILL, Institute for Juvenile Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

ALICE S. CARTER, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts

BARBARA DANIS, Institute for Juvenile Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

HELEN L. EGGER, Department of Psychiatry, Duke University

KATE KEENAN, Department of Psychiatry, University of Chicago

BENNETT L. LEVENTHAL, Institute for Juvenile Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

DOMENIC CICCHETTI, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University

KATIE MASKOWITZ, Institute for Juvenile Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

JAMES BURNS, Institute for Juvenile Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

MARGARET J. BRIGGS-GOWAN, Department of Psychiatry, University of Connecticut

REFERENCES

- 1.Keenan K, Wakschlag L. Are oppositional defiant and conduct disorder symptoms normative behaviors in preschoolers? A comparison of referred and non-referred children. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:356–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim-Cohen J, Arseneault L, Caspi A, Tomas M, Taylor A, Moffitt T. Validity of DSM-IV conduct disorder in 4 1/2-5 year-old children: a longitudinal epidemiological study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1108–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavigne J, Arend R, Rosenbaum D, Binns H, Christoffel K, Gibbons R. Psychiatric disorders with onset in the preschool years: I. Stability of diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1246–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speltz M, McLellan J, DeKlyen M, Jones K. Preschool boys with oppositional defiant disorder: clinical presentation and diagnostic change. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:838–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angold A, Egger H. Psychiatric diagnosis in preschool children. In: Carter A, DelCarmen-Wiggins R, eds. Handbook of Infant, Toddler and Preschooler Mental Health Assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004:123–139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egger H, Angold A. The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA): a structured parent interview for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in preschool children. In: DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A, eds. Handbook of Infant, Toddler and Preschool Mental Health Assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004:223–246. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egger H, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:313–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egger H, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter B, Angold A. The test-retest reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keenan K, Wakschlag L, Danis B,et al. Further evidence of the reliability and validity of DSM-IV ODD and CD in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angold A, Costello E. The relative diagnostic utility of child and parent reports of oppositional defiant disorders. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1996;6:253–259. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutter M. Child psychiatric disorders: measures, causal mechanisms, and interventions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pine D, Alegria M, Cook E Jr, et al. Advances in developmental science and DSM-IV. In: Kupfer D, First M, Regier D, eds. A Research Agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002:85–122. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell S. Behavior Problems in Preschool Children: Clinical and Developmental Issues, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, et al. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of infants and toddlers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(10 Suppl):21S–36S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benham A The observation and assessment of young children including use of the Infant-Toddler Mental Status Exam. In: Zeanah C, ed. Handbook of Infant Mental Health, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2000: 249–266. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeanah C, Boris N, Scott Heller S, et al. Relationship assessment in infant mental health. Infant Ment Health J. 1997;18:182–197. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell S, Breaux A, Ewing L, Szumowski E, Pierce E. Parent-identified problem preschoolers: mother-child interaction during play at intake and 1 year follow-up. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1986;14:425–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson EA, Eyberg SM. The dyadic parent-child interaction coding system: standardization and validation. J Consult Clinic Psychol. 1981;49:245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webster-Stratton C. Mother perceptions and mother-child interactions; comparison of clinic-referred and a nonclinic group. J Clinic Child Psychol. 1985;14:334–339. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mash E, Foster S. Exporting analogue behavioral observation from research to clinical practice: useful or cost-defective? Psychol Assess. 2001;13:86–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts M. Clinic observation of structured parent-child interactions designed to evaluate externalizing disorders. Psychol Assess. 2001;13: 46–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakschlag L, Leventhal B, Briggs-Gowan M, et al. Defining the “disruptive” in preschool behavior: what diagnostic observation can teach us. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2005;8:183–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hay D. The beginnings of aggression during infancy. In: Tremblay R, Hartup W, Archer J, eds. Developmental Origins of Aggression. New York: Guilford; 2005:107–132. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keenan K, Shaw D. The development of aggression in toddlers: a study of low-income families. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1994;22:53–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuczynski L, Kochanska G. Development of children’s noncompliance strategies from toddlerhood to age five. Dev Psychol. 1990;26:398–408. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tremblay R, Nagin R. The developmental origins of physical aggression in humans. In: Tremblay R, Hartup W, Archer J, eds. Developmental Origins of Aggression. New York: Guilford; 2005:83–106. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakschlag L, Danis B. Characterizing early childhood disruptive behavior: enhancing developmental sensitivity. In: Zeanah C, ed. Handbook of Infant Mental Health, 3rd ed. New York: Guilford; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakschlag L, Briggs-Gowan M, Carter A, et al. A developmental framework for distinguishing disruptive behavior from normative misbehavior in preschool children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48: 976–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kochanska G, Kuczynski L, Radke-Yarrow M. Correspondence between mothers’ self-reported and observed child-rearing practices. Child Dev. 1989;60:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cronbach L. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cicchetti D, Bronen R, Spencer S, et al. Rating scales, scales of measurement, issues of reliability resolving some critical issues for clinicians and researchers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleiss J. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. New York: Wiley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartko JJ. On the various intraclass correlation reliability coefficients. Psychol Bull. 1976;83:762–765. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lord C, Rutter M, Goode S, et al. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: a standardized observation of communication and social behavior. JAutism Dev Disord. 1989;19:185–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cicchetti D, Sparrow S, Volkmar F, Cohen D, Rourke B. Establishing the reliability and validity of neuropsychological disorder with low base rates: some recommended guidelines. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1991;3:328–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satorra A. Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heijmans R, Pollock D, A S, eds. Innovations in Multivariate Statistical Analysis: A Festschrift for Heinz Neudecker. London: Kluwer; 2000:233–247. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill C, Maskowitz K, Danis B, Keenan K, Burns J, Wakschlag L. Validation of a clinically sensitive observational coding system for parenting behaviors: the Parenting Clinical Observation Schedule (P-COS). Parenting Sci Pract. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw D, Bell R, Gilliom M. A truly early starter model of antisocial behavior revisited. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2000;3:155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hane A, Fox N, Polak-Toste C, Ghera M, Guner B. Contextual basis of maternal perceptions of infant temperament. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:1077–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werba B, Eyberg S, Boggs S, Algina J. Predicting outcome in parent-child interaction therapy: success and attrition. Behav Modif. 2006; 30:618–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]