Abstract

Objective. To provide optimal asthma care, community pharmacists must have advanced, contemporary knowledge, and the skills to translate that knowledge into practice. The development and evaluation of an innovative multi-mode education program to enhance pharmacists’ clinical knowledge and practical skills is described.

Methods. The online education modules were collaboratively developed alongside asthma and pharmacy organizations. The education program was comprised of five evidence-based education modules delivered online and a skills review conducted either in-person with real-time feedback (urban pharmacists) or via video upload and scheduled video-conference feedback (regional and remote pharmacists). A mixed methods approach was used to evaluate the feedback obtained from pharmacists to assess the content, efficacy, and applicability of the education.

Results. Ninety-seven pharmacists opted into the program and successfully completed all education requirements. A larger proportion of pharmacists did not pass trial protocol-based education modules on their first attempts compared to the number that passed the asthma and medication knowledge-based modules. Prior to skills review, the proportion of pharmacists demonstrating device technique competency was suboptimal. Pharmacists rated the education modules highly in both quantitative and qualitative evaluations and reported that the program adequately prepared them to better deliver care to asthma patients.

Conclusion. We developed, implemented, and evaluated a novel multi-mode asthma education program for community pharmacists that supports knowledge and practical skill development in this crucial area of patient care. The education program was well received by pharmacists. This form of education could be used more broadly in international collaborative trials.

Keywords: community pharmacy, asthma, education, inhaler technique, asthma management

INTRODUCTION

In Australia, one in nine people has asthma,1 and half of all asthma patients have inadequate control, despite the availability of effective medicines and known management strategies.2 Asthma management in Australia occurs principally within primary care. However, on average, Australians visit a pharmacy 14 times per year, and pharmacies are the most frequented health care venue by patients with asthma, which places them at a potential epicenter for asthma management.3,4 Upskilling the pharmacist workforce regarding asthma has been shown to have a significant impact on the clinical trajectory of patients with asthma within Australia and abroad.5-7 Pharmacists have also recognized the need for further education in order to effectively deliver specialized asthma services.8 Historically, education to upskill pharmacists in specialized clinical areas was delivered in face-to-face seminars,9 which were logistically challenging and costly for both organizers and participants, particularly participants in rural or remote areas. Geographical barriers to care are a serious concern in Australia, where approximately 20% of community pharmacies are located in regional or remote locations.10 Although online education modules from professional pharmacy and asthma bodies are now available to healthcare professionals for asthma management, a limitation in these self-paced asynchronous learning models is the absence of real-time, objective physical skills assessment; specifically, the explanation and demonstration of asthma devices. Pharmacists receive asthma device training in pharmacy school; however, their skills may not be reassessed or updated after they enter practice. Without reinforcement and ongoing assessment, their skills may deteriorate.11 Additionally, technological advances in drug delivery have seen the introduction of numerous devices in recent years, and competency in the use and demonstration of these devices is required for pharmacists to deliver optimal patient care.

Online platforms may provide a means to deliver efficient and cost-effective education and assessment that could facilitate not only distance learning but international programs. This study describes the development of a novel multi-mode education program that aims to enhance both pharmacists’ clinical knowledge and practical skills in asthma management, assess pharmacists’ performance, and provide end-user evaluation using a mixed-methods approach.

METHODS

The education program was designed as part of a larger two-arm, multi-site, clustered, randomized implementation trial to compare asthma-related outcomes in patients receiving a specialized Pharmacy Asthma Service (PAS) with a comparator arm that received standard pharmacy care. This parent trial ran from July 2018 to February 2020 and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of The University of Sydney, Curtin University, and The University of Tasmania.12

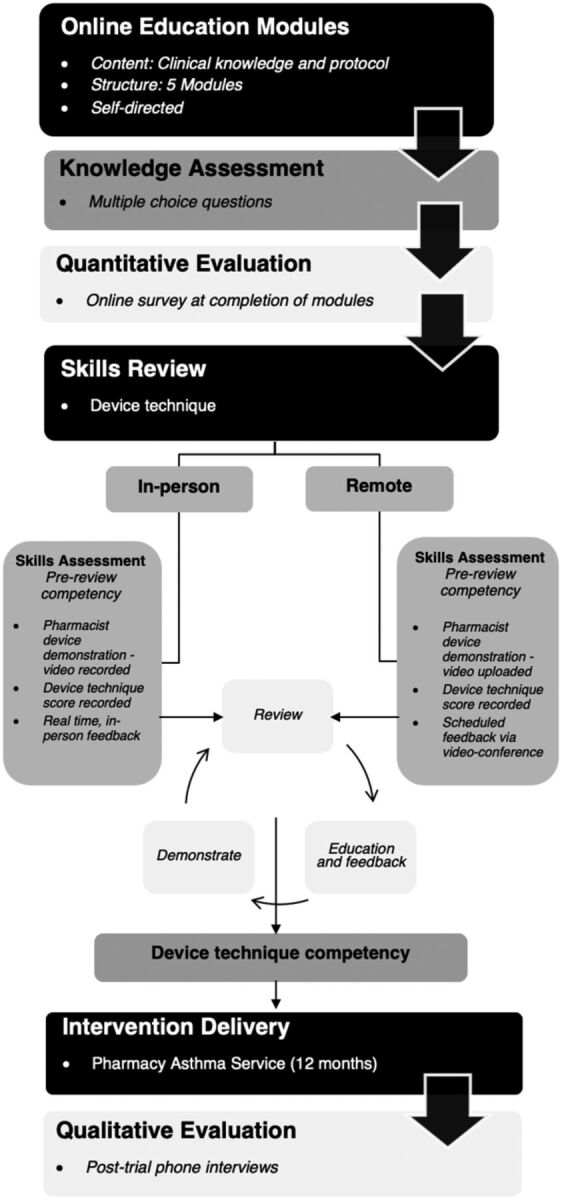

Pharmacists delivering the PAS were required to pass a multi-mode education program comprised of both theoretical and skills-based components to ensure they had the advanced clinical knowledge and skills required to deliver and comply with the PAS protocol (Figure 1). The comparator pharmacists required only protocol training.

Figure 1.

A multi-mode educational program for pharmacists participating in the Pharmacy Asthma Service for patients in Australia.

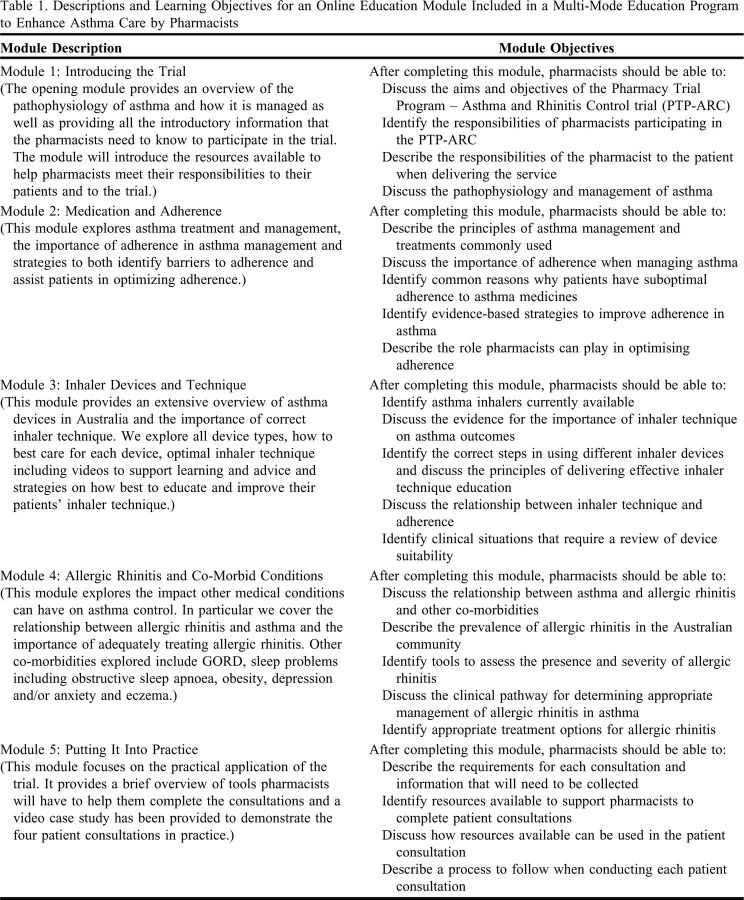

Five online education modules for pharmacists were developed by the project team and hosted on Pharmaceutical Society of Australia’s (PSA’s) online education platform. The modules included content and videos based on current guidelines and evidence-based research on asthma care. The PSA is an Australian Government-recognized, national professional pharmacy organization committed to providing high-quality practitioner development and practice support. The use of the online modality ensured accessibility to education for all pharmacists in the trial, irrespective of location. The online modules covered background material regarding asthma and the study, asthma medications and adherence, inhaler devices and technique, management of co-morbid allergic rhinitis, the trials protocol pathway, and an illustrative case study. The module descriptions and associated learning objected are illustrated in Table 1.13

Table 1.

Descriptions and Learning Objectives for an Online Education Module Included in a Multi-Mode Education Program to Enhance Asthma Care by Pharmacists

For each module, a lead researcher produced the initial outline of the required content, resources, and competence level required. This was reviewed by the project team, including the PSA, which was responsible for ensuring that the final module composition and delivery were in line with adult learning principles.14 Pharmacists completed the modules in a self-directed manner, and the education platform could be exited and accessed again at a time suitable for the pharmacist. Content of the online education modules was presented in a variety of formats, including text, graphics, tables, videos, and interactive elements, within an easy-to-navigate framework. To illustrate how the evidence-based interventions could be translated into practice for the trial and how to engage with patients when delivering asthma care, an exemplar case study was filmed and included in module 5. The modules were accredited continuing professional development (CPD) activities and took approximately 5.5 hours to complete.

The online education modules had to be completed sequentially, and each module was followed by a set of multiple-choice questions to assess the learner’s knowledge of asthma, its management, and clinical application of the knowledge acquired.14 All modules included five MCQs, except for module 4 (allergic rhinitis and co-morbid conditions), which included eight questions. A passing grade was defined as correctly answering at least 75% of the MCQs in each module assessment. Pharmacists were allowed two attempts to pass each module. If further attempts to pass were required, a member of the project team contacted the pharmacist and visited them to provide individual assistance.

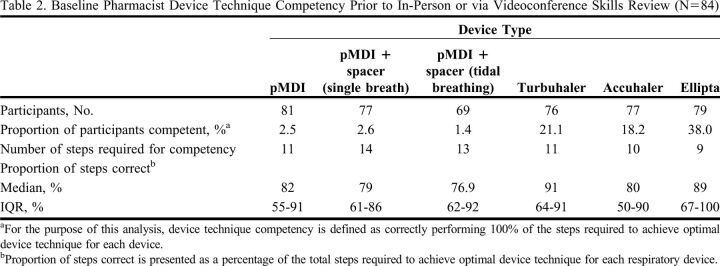

Following completion of online education module 3 (on inhaler devices and technique), each pharmacist received a skills review by trained device technique reviewers on five of the most common inhaler devices used in Australia: the pressured metered-dose inhaler (pMDI); pMDI with spacer (both tidal and single-breath method) representative of that used in Ventolin (GlaxoSmithKline) and Seretide pMDI (GlaxoSmithKline); and dry powder inhalers, including Turbuhaler (AstraZeneca), Accuhaler (GlaxoSmithKline), and Ellipta (GlaxoSmithKline). All reviewers were trained by a senior member of the project team to ensure consistency in delivery technique. Pharmacists were required to demonstrate the devices in accordance with the National Asthma Council Australia checklists.15 Placebo (practice) devices were provided to each participating pharmacy.15 In addition to correcting pharmacists’ delivery technique, pharmacists also were offered advice on how to better engage their patients and correct their patients’ technique. A video of the pharmacist’s pre-review technique demonstration was recorded for all assessed device types. In accordance with literature, this was then followed by feedback, and the pharmacists were asked to re-demonstrate until the reviewer was satisfied with the pharmacist’s competency in demonstrating use of all five devices.15-17 The type of review was determined by the pharmacy’s proximity to the research sites and available trainers: either in-person review, with feedback and advice provided immediately (urban pharmacists), or via prerecorded demonstration videos upload of to a personal Dropbox link, with feedback provided via a scheduled videoconference (regional and remote pharmacists). Skills reviews were organized by the project team and conducted at a time convenient for the pharmacists (Figure 1). Videos of each pharmacist’s pre-review skillset was used to calculate a device technique score for each pharmacist. This score was presented as a percentage of the steps performed correctly vs the number of steps required to achieve device technique competency as per NAC device technique checklists.15 For this analysis, device technique competency was defined as a device technique score of 100%.

A mixed-methods approach was used to evaluate the education program. Feedback was sought from pharmacists at the completion of all five online education modules via an optional online survey. Using five-point Likert-type scales, pharmacists were asked to rate the content and efficacy of the online education modules, including the case study videos presented in module 5, in improving their knowledge and confidence in the areas of adherence, device technique, and allergic rhinitis. They were also asked to indicate any additional help they required to improve their skills, knowledge, and/or clinical application.

Qualitative telephone interviews were conducted with at least one pharmacist from every pharmacy that completed a full 12-month PAS with at least one patient. Interviews were conducted from January 2020 to March 2020, within six months of the pharmacy completing the PAS. Pharmacists were asked to discuss how well the education program equipped them to deliver the PAS, and to expand on what worked particularly well, or if there were any gaps in the education program. All interviews were conducted by telephone using a project-specific interview guide. This paper only reports feedback relevant to the education components. Interviews were conducted by one of three facilitators. All interviewers underwent the same training to ensure consistency. Each of the interviewer’s first interview transcripts were reviewed by four members of the research team, with feedback provided to assist coaching and ensure the appropriateness of the interview guide. The interviewer allocated to each pharmacist was one with whom the pharmacist had no prior communication or contact during the trial. All audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and given unique identifiers. Transcripts were cross-checked against the original audio file by the two other interviewers who did not conduct the interview to ensure accuracy of the final transcripts. The scores for each online module assessment, device technique review, and responses to evaluation questions for pharmacists in the intervention group were collated into an Excel spreadsheet and uploaded to SPSS, version 25, where descriptive and bivariate statistics were applied. To assess the impact of the method of skills review (ie, in-person or remote) on pharmacist device technique performance, pharmacist’s device technique scores were compared using a Mann-Whitney U test. A significance level of p<.05 was used for all statistical procedures.

Qualitative interview transcripts were imported into NVivo 12 (QSR International) to facilitate inductive thematic analysis. All transcripts were analyzed on a line-by-line basis, through a method of constant comparison and feedback regarding pharmacist education was extracted by one member of the research team. Key concepts were identified and reviewed, and a coding frame was developed and subsequently applied to all transcripts.

RESULTS

Of the 171 pharmacists from 64 pharmacies in New South Wales (NSW), Tasmania, and Western Australia (WA) who expressed an interest in participating in the education program, 113 (66.1%) completed the online education modules and 107 (62.6%) completed the subsequent skills assessment, and 97 pharmacists fulfilled both education requirements.

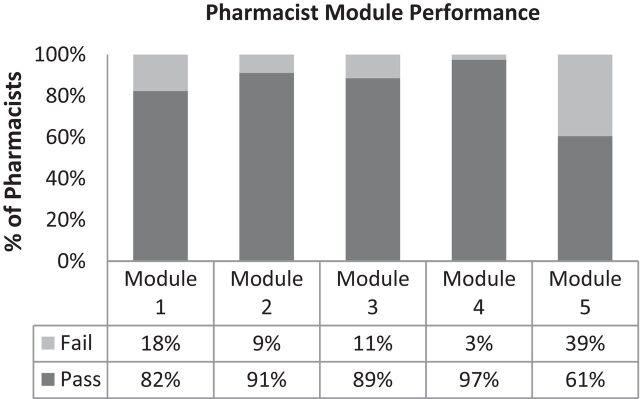

A larger proportion of pharmacists did not receive a passing assessment on module 1, which covered background to asthma, study background, and plan, and/or module 5, protocol pathway and case study on their first attempt compared to the proportion of pharmacists’ who did not pass the other three modules (Figure 2). Seventy-four skills reviews were conducted in person and 33 were conducted via video upload and videoconference feedback. In-person reviews required an average of 20-30 minutes per pharmacist. Pre-review competency videos were successfully obtained and uploaded for 78% (n=84) of the reviewed pharmacists, with 33 videos remotely uploaded and 52 obtained in person. On initial assessment, most pharmacists were not competent in the use of any of the assessed devices (Table 2). None of the pharmacists were initially competent in all of the device types assessed. A higher proportion of pharmacists were competent in the use of dry powder devices compared to pMDI’s and pMDI/spacer combinations. All 107 pharmacists were 100% competent by the end of the review. Patients who prerecorded their technique demonstration performed significantly better at baseline for pMDI with spacer (single-breath method) (p=.05), Turbuhaler (p=.03), Accuhaler (p=.01) and Ellipta (p=.01) device types.

Figure 2.

Pharmacists’ performance in each online education module on their first attempt as part of their participation in the Pathway to Pharmacy Asthma Service (N=113).

Table 2.

Baseline Pharmacist Device Technique Competency Prior to In-Person or via Videoconference Skills Review (N=84)

The optional evaluation survey for the online education modules, which used a series of five-point Likert scales, was completed by 23% of pharmacists. Over 80% of the pharmacists who provided feedback agreed that the online education module content (including the example case study) achieved the learning objectives and met their expectations. Over 55% of the pharmacists agreed that the modules were relevant to the management of their asthma patients. Most pharmacists (81%) rated the format of the modules highly, and 63% agreed that the modules presented an appropriate amount of content. Regarding the efficacy of the modules, most pharmacists reported that the online education modules greatly improved their knowledge about adherence (65% agreed), device technique (61% agreed) and co-morbid allergic rhinitis (52% agreed), and greatly improved their confidence in assisting patients in these areas (69%, 64%, and 56% agreed, respectively). There were greater differences of opinion regarding the effectiveness of the allergic rhinitis module, with a larger percentage of pharmacists selecting a neutral response (20%) regarding whether this module impacted knowledge and confidence levels.

In terms of the free-text feedback provided on the survey instrument, 71% of pharmacists reported that continual and regular evidence-based refresher training would help to enhance their knowledge. More time (14%) and practice (14%) were also mentioned as ways to enhance knowledge. Fifty-six percent of responding pharmacists reported that practice and real-world experience would enhance the knowledge gained from the modules. Clearer software instruction (11%), more time in day-to-day practice to enact new knowledge and counsel patients (11%), and follow-up device reviews (22%) were also requested. Most pharmacists reported they were confident about translating the knowledge obtained from the online education modules into practice (86%). When pharmacists were asked what would improve their ability to apply skills in the workplace, 75% reported more time and resources, while 12.5% mentioned having their own set of placebo devices (which were to be provided) and greater self-confidence about their knowledge of the products.

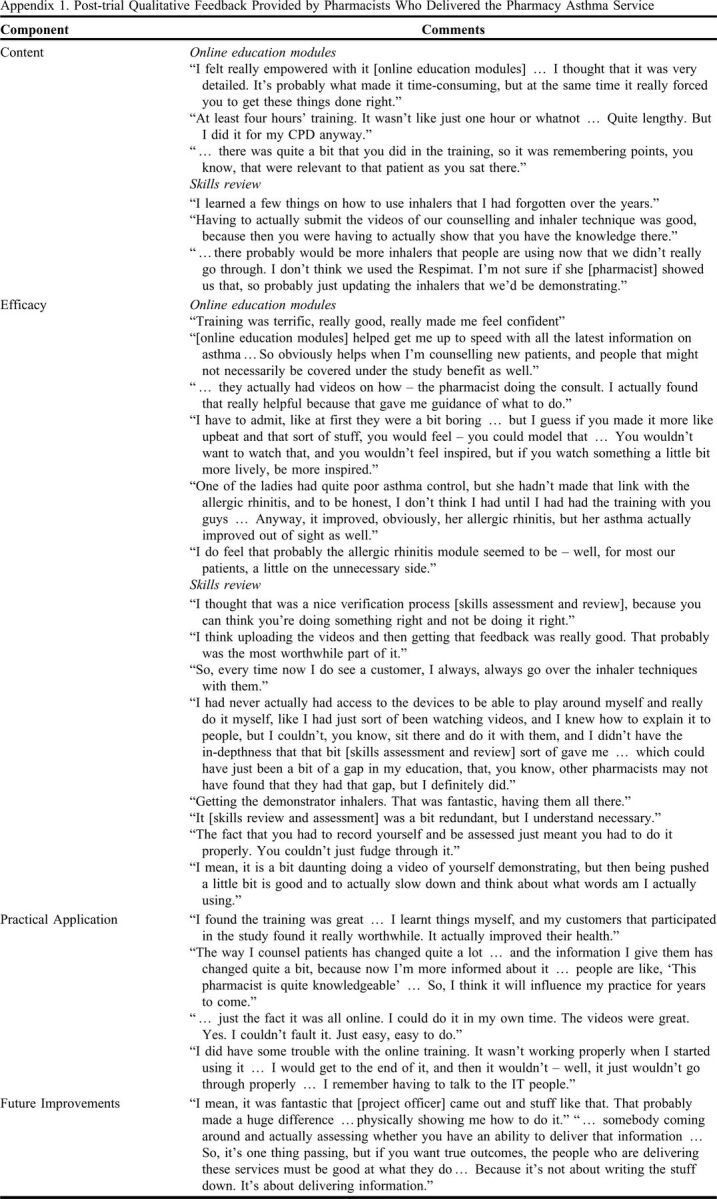

Following completion of the parent trial, qualitative interviews were conducted with 48 pharmacists (representing 42 pharmacies) who had fulfilled all education requirements. A summary of feedback received is presented below, and exemplar comments made by pharmacists are presented in Appendix 1. The online education module content was described as helpful, detailed, and thorough by most respondents. Most pharmacists who were satisfied with the modules explained that the modules provided an in-depth refresher to solidify their knowledge regarding asthma management. For a few pharmacists, the detailed nature of the online education modules made participation time consuming, but they were happy to complete them to earn the associated CPD points. For others, this meant it was difficult to recall important points once they were face-to-face with the patient. Most pharmacists described the skills review as a beneficial refresher that was able to fill in steps they may have forgotten over time or may have been doing incorrectly. Two pharmacists specified that they would have liked more inhalers to be reviewed and assessed, particularly, new-to-market devices such as the Spiromax (TEVA Pharmaceuticals) or Respimat (Boehringer Ingelheim). When discussing the efficacy of the education modules, several pharmacists mentioned that the online modules provided them with new knowledge that empowered them to counsel their patients more effectively. Some pharmacists believed that the case study videos in Module 5 were helpful in modelling how the intervention should be delivered within pharmacies. One pharmacist, however, felt the protocol videos were lackluster and an effort should be made to make them “a little more upbeat” to inspire pharmacists.

Appendix 1.

Post-trial Qualitative Feedback Provided by Pharmacists Who Delivered the Pharmacy Asthma Service

Feedback regarding the efficacy of the allergic rhinitis component of the education was mixed. One pharmacist believed this information was helpful and responsible for health improvements in one of her patients. Another participant believed more information about allergic rhinitis should have been provided, while other pharmacists felt the allergic rhinitis component of the education modules was unnecessary.

A few pharmacists explained that the skills review boosted their confidence in approaching patients and counselling them on device technique. Some pharmacists mentioned that the placebo respiratory devices were helpful to their everyday practice and enhanced their counselling ability. Half of the pharmacists who mentioned the benefit of the placebo inhaler devices were from regional or remote areas. Regarding personal video uploads, a few pharmacists described the process as “daunting” or “nerve racking” as they were not used to having to film themselves. Despite this, they described the process as worthwhile and the experience as positive. Only one pharmacist reported difficulty in uploading their videos. Two pharmacists commented that the skills assessment was not necessary. Almost all pharmacists interviewed stated that the education program had equipped them well to deliver the PAS in practice and had given them the confidence to counsel patients more effectively regarding asthma, asthma medications, and device technique. Several pharmacists also mentioned this had enabled them to directly improve the health of their patients. Two pharmacists, who also had asthma, added that they were able to improve their own asthma control because of the upskilling.

Few comments were offered about the mode of education. Two pharmacists from urban pharmacies appreciated the convenience of the online modules, although one pharmacist experienced some frustrating initial technical issues with the online education modules. Most pharmacists could not identify any gaps in the education program. Some pharmacists pointed out that a larger focus on recruitment training would be helpful, as well as more technical training to operate the custom-designed intervention documentation software for the parent trial. Several pharmacists received on-site support by the project officers, which reportedly improved the pharmacists’ understanding of technical aspects of delivering the service. One pharmacist also mentioned that the skills review should offer more explanation as to why each step is necessary and added that pharmacists should be assessed on their delivery of information obtained from the education program as this is important for generating positive outcomes in patients. One pharmacist suggested that updates be made to the modules as changes in guidelines occur.

DISCUSSION

We successfully developed, implemented, and evaluated a specialized asthma education program that uses online platforms to deliver accessible education for asthma care. The program included components of knowledge and skills-based asthma education, as well as modules on implementing interventions. Pharmacists performed well in all knowledge-based modules. The education program was rated highly in terms of content, efficacy, and applicability in our mixed methods evaluation, which assessed the education quantitively upon completion of the education modules and qualitatively via interviews conducted at the completion of the trial.

Our education program was novel in that it used remote training and assessment of a skill (device technique) rather than asking community pharmacists to travel to complete training face to face. We have shown that this method is feasible and successful as all pharmacists, with feedback and coaching, achieved optimal device technique (100% correct). This means that education for new services can be implemented across rural and remote sites as well as urban pharmacies efficiently and without sacrificing practical skill development. This is a distinct advantage for pharmacists practicing in more remote parts of Australia and in other challenging circumstances, such as during a pandemic, where traditional face-to-face training is not possible. Additionally, based on the success of this model with respect to asthma education, future research could explore translation of the hybrid education model, to other therapeutic areas that require both theoretical knowledge and skills-based training for effective patient counselling, eg, the use of glucometers and insulin devices in diabetes management.

Interestingly, a greater proportion of pharmacists failed the protocol-based online education modules on their first attempt compared to other modules. Pharmacists were initially unfamiliar with the clinical actions and processes of the PAS and performed poorer in these assessments than in modules covering the clinical aspects of asthma and its management. Despite this, most pharmacists reported that they were confident in applying the knowledge into practice in post training evaluation.

The benefit of one-on-one device technique counselling delivered by pharmacists in improving patients’ use of their asthma device(s) is well reported.16-21 Solid theoretical grounding in asthma, drug information, and device technique from the online education modules, however, did not translate to optimal practical skills when pharmacists were assessed on their demonstration of key devices. This illustrates that a gap between theoretical mastery and practical competency in using respiratory devices was prevalent among the pharmacists assessed. Whether this was the result of lack of access to practical training or inaccessibility of placebo devices is unknown. The need for hands-on skill-based education for pharmacists to ensure adequate patient counselling and the promotion of quality use of medication is evident. Our education program was able to bridge this gap. Previous studies have shown similarly low levels of competency among healthcare practitioners and patients alike,5,16,20-22 which is perhaps expected, as poor understanding of correct device technique by healthcare professionals will translate to poor patient understanding and inhaler use.21

Regional and remote pharmacists were required to submit prerecorded demonstration videos for their skills review, and later were provided feedback via a scheduled videoconference. As pharmacists had access to the NAC checklists and associated videos via the online training modules, these pharmacists may have practiced and re-recorded their demonstration multiple times prior to submission, placing them at an advantage over pharmacists who underwent in-person reviews. However, despite this opportunity to perfect their submission, no pharmacist was competent in all assessed device types and overall competency levels were poor. Interestingly, a higher proportion of pharmacists were competent in the use of Turbuhaler (AstraZeneca), Accuhaler (GlaxoSmithKline), and Ellipta (GlaxoSmithKline) devices compared to pMDI and pMDI/spacer combinations. A possible explanation is that dry powder inhalers are simpler to use than pMDI devices, which require greater coordination upon inhalation.23-25

How often pharmacists’ practical skills need to be reviewed requires further investigation. In any new trial, it would be beneficial to incorporate process evaluation such that knowledge and skills are assessed periodically to determine when and if competency gaps develop.19,26,27 Future research to also quantify or assess a pharmacist’s ability to deliver new knowledge in their counselling via mystery shopper methods would be beneficial.

The allergic rhinitis module was included as the literature has shown that only 15% of patients leave the pharmacy with appropriate medication with or without pharmacist intervention.28 We were surprised that pharmacists were more divided in their opinions on the allergic rhinitis module. For many, this module had much less impact on their knowledge or confidence than in the other learning areas. These findings were consistent with the pharmacist interview data. This could be because most treatments for allergic rhinitis are available in pharmacies without a prescription, and pharmacists believe they have sufficient baseline knowledge.

In both forms of evaluation, the education program was well received and boosted pharmacists’ confidence and empowerment to counsel patients with asthma. Our design processes were informed by Adult Learning Principles and best-practice design for online learning; however, feedback emerged that was suggestive of pharmacists' specific needs.14 The feedback collected will be valuable in refining the education program design.

Despite the online education modules being around 5.5 hours in total, and the fact that the time required was mentioned in the expression of interest document, some pharmacists found the workload excessive. This may have influenced low completion rates, which were unexpected given that pharmacists volunteered to be included in the trial. Pharmacists who did not complete the program may have been unable to commit to providing the trial asthma management service; thus, their withdrawal at the training stage could have been indicative of their capacity for participation in research and new services. As there are considerable resources involved in upskilling pharmacists for new services, it would be valuable in the future to determine who is likely to take up the knowledge and transfer that into action.

Limitations

Quantitative feedback was not collected from all pharmacists undertaking the education program, as the survey was optional. Thus, the comments made regarding relevance to practice and time taken may not be representative of the entire cohort of pharmacists involved. Our qualitative evaluation of the education modules provided feedback from participants who had completed the entire trial and were able to reflect on the utility of their training. However, this meant that recall bias may have occurred.

Regarding device technique, the number of attempts required to achieve competency was not recorded as the focus was on ensuring competency before commencing service provision. Similarly, a pre/post design was not relevant to measure improvement in knowledge, and instead focused on assurance of requisite knowledge prior to implementation of the asthma management service. Our data report immediate performance in knowledge recall and application of theory, and attainment of skills in demonstrating device technique and so, retention of pharmacists’ learning was not measured.

CONCLUSION

Our data demonstrate the feasibility of implementing a blended-learning program to enhance asthma care by pharmacists that was comprised of a modularized online self-directed theory component and online assessments, and supplemented by in-person or online skills assessments. This form of education is suitable for use in remote areas and could be used more broadly in international collaborative trials. An upskilled pharmacist workforce will help to pave the way for effective task sharing in patient asthma management within primary care, which may reduce asthma burden and costs to the individual, their community, and the healthcare system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by the Commonwealth of Australia as represented by the Department of Health via The Sixth Community Pharmacy Agreement (6CPA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey - First results - Australia 2017-2018. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://iepcp.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/4364.0.55.001-national-health-survey-first-results-2017-18.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed April 12, 2022.

- 2.Reddel HK, Sawyer SM, Everett PW, Flood PV, Peters MJ. Asthma control in Australia: a cross-sectional web-based survey in a nationally representative population. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2015;202(9):492-497. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2015/202/9/asthma-control-australia-cross-sectional-web-based-survey-nationally. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Pharmacy Guild of Australia. Vital facts on community pharmacy. https://www.guild.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/12908/Vital-facts-on-community-pharmacy.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed April 12, 2022.

- 4.The Pharmacy Guild of Australia. The Guild Digest, A Survey of Independent Pharmacy Operations in Australia for the Financial Year 2017-18. https://www.guild.org.au/resources/business-operations/guild-digest. Published 2019. Accessed April 12, 2022.

- 5.Armour C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Brillant M, et al. Pharmacy Asthma Care Program (PACP) improves outcomes for patients in the community. Thorax . 2007;62(6):496-502. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17251316/. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armour CL, Reddel HK, LeMay KS, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of an evidence-based asthma service in Australian community pharmacies: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. The Journal of Asthma . 2013;50(3):302-309. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23270495/. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordois A, Armour C, Brillant M, et al. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of a Pharmacy Asthma Care Program in Australia. Disease Management & Health Outcomes . 2007;15(6):387-396. 10.2165/00115677-200715060-00006. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qazi A, Saba M, Armour C, Saini B. Perspectives of pharmacists about collaborative asthma care model in primary care. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy . 2021;17(2):388-397. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1551741119311234. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Cardenas V, Armour C, Benrimoj SI, Martinez-Martinez F, Rotta I, Fernandez-Llimos F. Pharmacists' interventions on clinical asthma outcomes: a systematic review. The European Respiratory Journal ,. 2016;47(4):1134-1143. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26677937/. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Pharmacy Guild of Australia. Access to Community Pharmacy Services in Rural/ Remote Australia. https://www.guild.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/6164/Access-to-Community-Pharmacy-Services-in-Rural-Remote-Australia-.pdf. Published 2012. April 12, 2022.

- 11.Basheti IA, Armour CL, Reddel HK, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Long-term maintenance of pharmacists' inhaler technique demonstration skills. American Journal of Pharmacy Education . 2009;73(2):32-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19513170. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Registry ANZCT. Trial Review - Pharmacy Trial Program (PTP)- Getting asthma under control using the skills of the community Pharmacist. https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=374558&isReview=true. Published 2018. Accessed April 12, 2022.

- 13.French D. Internet Based Learning: An Introduction and Framework for Higher Education and Business. United Kingdom: Kogan Page; 1999. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=jkM9AAAAIAAJ. Accessed April 12, 2022.

- 14.Cercone K. Characteristics of Adult Learners With Implications for Online Learning Design. AACE Review (formerly AACE Journal) . 2008;16(2):137-159. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/24286/. Accessed April 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Asthma Council Australia. Inhaler Technique Checklists. https://www.nationalasthma.org.au/living-with-asthma/resources/health-professionals/charts/inhaler-technique-checklists. Published 2016. Accessed April 12, 2022.

- 16.Basheti IA, Armour CL, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ, Reddel HK. Evaluation of a novel educational strategy, including inhaler-based reminder labels, to improve asthma inhaler technique. Patient Education and Counselling . 2008;72(1):26-33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18314294/. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Axtell S, Haines S, Fairclough J. Effectiveness of Various Methods of Teaching Proper Inhaler Technique. J Journal of Pharmacy Practice . 2017;30(2):195-201. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26912531/#:∼:text=Conclusion%3A%20A%202%2Dminute%20pharmacist,implications%20of%20improper%20inhaler%20use. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosnic-Anticevich SZ, Stuart M, Mackson J, et al. Development and evaluation of an innovative model of inter-professional education focused on asthma medication use. BMC Medical Education . 2014;14:72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24708800/. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ndukwe HC, Shaul D, Shin J, et al. Assessment of inhaler technique among fourth-year pharmacy students: Implications for the use of entrustable professional activities. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning . 2020;12(3):281-286. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877129719301182. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ovchinikova L, Smith L, Bosnic-Anticevich S. Inhaler Technique Maintenance: Gaining an Understanding from the Patient's Perspective. Journal of Asthma . 2011;48(6):616-624. 10.3109/02770903.2011.580032. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price D, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Briggs A, et al. Inhaler competence in asthma: Common errors, barriers to use and recommended solutions. Respiratory Medicine . 2013;107(1):37-46. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0954611112003587. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basheti IA, Reddel HK, Armour CL, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Improved asthma outcomes with a simple inhaler technique intervention by community pharmacists. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology . 2007;119(6):1537-1538. 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.02.037. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerwin EM, Preece A, Brintziki D, Collison KA, Sharma R. ELLIPTA Dry Powder Versus Metered-Dose Inhalers in an Optimized Clinical Trial Setting. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice . 2019;7(6):1843-1849. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213219819302004. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Svedsater H, Jacques L, Goldfrad C, Bleecker ER. Ease of use of the ELLIPTA dry powder inhaler: data from three randomised controlled trials in patients with asthma. NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine . 2014;24(1):14019. 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.19. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Palen J, Thomas M, Chrystyn H, et al. A randomised open-label cross-over study of inhaler errors, preference and time to achieve correct inhaler use in patients with COPD or asthma: comparison of ELLIPTA with other inhaler devices. NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine . 2016;26(1):16079. 10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.79. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosnic-Anticevich SZ, Stuart M, Mackson J, et al. Development and evaluation of an innovative model of inter-professional education focused on asthma medication use. BMC Medical Education . 2014;14(1):72. 10.1186/1472-6920-14-72. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price D, Keininger DL, Viswanad B, Gasser M, Walda S, Gutzwiller FS. Factors associated with appropriate inhaler use in patients with COPD - lessons from the REAL survey. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder . 2018;13:695-702. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29520137. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan R, Cvetkovski B, Kritikos V, et al. The Burden of Rhinitis and the Impact of Medication Management within the Community Pharmacy Setting. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice . 2018;6(5):1717-1725. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29606639/. Accessed April 12, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]