Abstract

Objective. To evaluate the introduction of 10 Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) sessions into year 2 of a Bachelor of Pharmacy (BPharm) program with the aim of assisting students in developing the skills and attitudes required for inclusive practice.

Methods. The evaluation used a cross-sectional study design. All members of the first two successive student cohorts to complete multiple VTS sessions completed a 38-item online reflective questionnaire exploring student perceptions of competency development, transference, and session acceptability. Students were asked for their consent to include their responses in a research study. Closed-question responses were analyzed to produce descriptive statistics. Free-text responses were categorized and quantified using an inductive approach and manifest content analysis.

Results. Fifty-six percent of the students (98 of 174) allowed their responses to be included in the study. Students generally believed the sessions had supported their development of person-centred communication, cultural competence, and critical thinking skills. The minimum level of agreement that improvement in an area occurred was 74.5%. Free-text responses revealed the perception of additional skill and attitude development. Sixty percent of participants had thought about the VTS questions or used what they had learned in the VTS sessions in other settings. Eighty-six percent of students agreed that content on VTS should remain in the BPharm curriculum.

Conclusion. Incorporating regular VTS sessions into the second year of a BPharm program was acceptable to students. Data suggest that inclusion of multiple VTS sessions is a valuable addition to the pharmacy curriculum, offering affective learning experiences which support development and transference of key skills and attitudes relating to the provision of inclusive person-centred care.

Keywords: Visual Thinking Strategies, patient-centred care, pharmacy education, affective learning, competencies, transfer of learning

INTRODUCTION

In New Zealand, as in other parts of the world, achieving health equity is a goal of many health and disability systems and organizations.1 -5 Consequently, pharmacy services should be provided in a person-centered and inclusive manner as every individual has the right to have their needs understood and receive health services in such a way that their wishes are taken into account and their values and beliefs are accommodated.6,7 In health care, working inclusively has been defined as engaging authentically with people and working effectively in different types of relationships that may involve “ambiguity, contradiction, uncertainty and paradox.”8 Demographically, New Zealand is considered to be both a bi-cultural and multicultural country.9 As such, culturally safe practices are an important element of inclusive practice.10 Culturally safe practices require health professionals to consider power dynamics and imbalances within therapeutic relationships, patients’ rights, and self-reflecting on the potential impact of their own culture and biases on their interactions with others.11 -14 Relatedly, cultural competence in a global context can be grouped into broad domains, of an awareness of one’s own cultural biases and background, knowledge of other cultures, and an ability to respectfully manage the dynamics of difference.15 -18 However, supporting undergraduate pharmacy students in their development of the skills and attitudes required to practice in such an inclusive manner can be challenging given curricular constraints. Our national registration competence standards19 require that a sensitive, proactive approach to teaching be taken,20 with a focus on the affective domain of learning.21,22

Visual thinking strategies is a pedagogical method that was developed outside of health care, originally designed by Abigail Housen and Philip Yenawine to create inclusive discussions that foster person-centered competency development. It uses small group teaching sessions to explore and make sense of creative works using a structured facilitation method.23,24 Pedagogy that uses VTS is constructivist25 and aligns with Bruner’s view of problem-solving stages in that it involves exploration, extraction of relevant information, simplification, and organization of information.26 Originally designed to assist children with developing visual literacy and other transferable skills, VTS has increasingly been used in health professional curricula, often as an elective option, for a variety of purposes, including improving both observation skills and tolerance for ambiguity development,27 and for building listening, analytical, and teamwork skills.28

In 2016, faculty at the University of Auckland piloted a project weaving VTS sessions throughout the entry year clinical and professional skills modules in the revised, integrated Bachelor of Pharmacy (BPharm) curriculum. These modules enabled students to develop knowledge and skills needed for competent pharmacy practice and included aspects of professionalism, clinical communication, and human behavior.

The VTS sessions were designed to support development of students’ transferable competencies and attitudes relating to inclusive person-centered practices, including communication, cultural safety, critical thinking, and reflection. These aspects are important globally for inclusive practice as they facilitate relationship building and meeting the needs of diverse health consumers. However, somewhat absent from clinical education literature are practicable, low-cost classroom-based learning activities that can support development of such transferable competencies.

Our research aimed to address this gap by exploring three aspects of VTS implementation in our BPharm curriculum. First, we evaluated student perceptions of the effect of VTS sessions on their skills and attitude development relating to providing inclusive, person-centered care. Second, we examined the extent to which transfer of these skills to other settings, as reported by students, occurred since transfer of learning from academic to real-world settings is a challenging goal to realize.29,30 Finally, this inquiry was important as curricula are “crowded spaces”31 and, as such, we needed to ensure that students were accepting of VTS and that the method was providing the intended experiential development and transfer of competencies.

METHODS

During year 2 of the BPharm program, students participated in 10 VTS sessions with eight to 18 students per session over two semesters. The sessions were inserted into the final part of two-hour pharmacy practice tutorials, and covered topics such as communication and professionalism. The tutorials were streamlined to accommodate VTS. At the beginning and end of the year, students individually wrote about a creative work (the same visual image) using the required questions from the VTS methodology: “What’s going on in this image?” “What do I see that makes me say that?” and “What more can I find?”24

Each approximately 30-minute session involved small group oral discussions using the same questions, where between one and three images (usually two) were discussed. Sessions occurred in standard teaching spaces and used projected images chosen to engage students and explore aspects of inclusion. Adhering to the VTS method, presented images became deliberately more ambiguous, and therefore challenging to interpret, as the year progressed. To maintain engagement, part way through the series, students could choose from several images presented to them. Following Housen’s image selection method, we began the first VTS session with a less complex image, July 7 (a painting by Frederick D. Jones, 1958),32 moved to a more abstract image with image 2, Roots (a painting by Frida Kahlo, 1943),33 and finished with an even more ambiguous image that we believed had the greatest potential for multiple interpretations, image 3, Daughter (a painting by Gregory Crewdson, 2002)34 (Images of the artworks can be accessed through Google.com image searches.)

To encourage transference of VTS ideas and skills, the writing was purposefully linked to a four-part 2,500 word assignment. This incorporated: pre/post VTS writing sessions, quality and interpretation comparisons of the two pieces of writing relating to the image, anonymous peer-review using a web-based tool (each post submission reviewed by two peers), reflections on their learning through the VTS sessions, and the potential impact of VTS on their future pharmacy practice. Images were also linked to other course activities relating to culture and communication.

Study Design

The evaluation used a cross-sectional study design. In November 2017, all members of two successive cohorts of students completing the VTS sessions were asked to complete a 38-item online reflective questionnaire. Completion of the questionnaire addressed some of the course professional learning outcomes and the study aims. The two VTS facilitators who were also research team members developed the questionnaire. The questionnaire, which was administered through Qualtrics, used Likert-scale, binary fixed choice items and explanatory, free-text responses. The questionnaire collected high-level demographic data, self-assessed skills development, self-reported transference of skills, and student views on the acceptability and value of the sessions. Completing the questionnaire was compulsory as it was considered part of the reflective learning component of the program. However, students were allowed to decide whether their responses would be included in the research project.

The study exclusion criterion was any student who had not participated in a year of VTS sessions and/or had not agreed to participate in the study. To preserve student confidentiality the data were downloaded into a spreadsheet by a non-pharmacy research team member. That team member separated out and de-identified the responses of those students agreeing to participate in the study, prior to TA and LP being given access to the data. All research participants were entered into a prize draw to win one of two $50 cafe vouchers, which were paid for out of the school’s teaching fund.

Closed-question responses were analyzed in Excel. Open-text responses were categorized and quantified using an inductive approach and manifest content analysis.35,36 Open text responses were categorized separately before comparing and agreeing upon the final categories and themes. Exemplar quotes from the explanatory open-text responses were used to enrich and illustrate the quantitative findings.

This research was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee. A short article relating to collaborative skills development arising from this study was published in 2020.37 This paper reports on findings related to inclusive practice.

RESULTS

All 174 students who had completed their second BPharm year in 2016 and 2017 were invited to participate. Ninety-eight (56%) students consented to their responses being included in this study (25/76 from cohort one; 73/98 from cohort two).

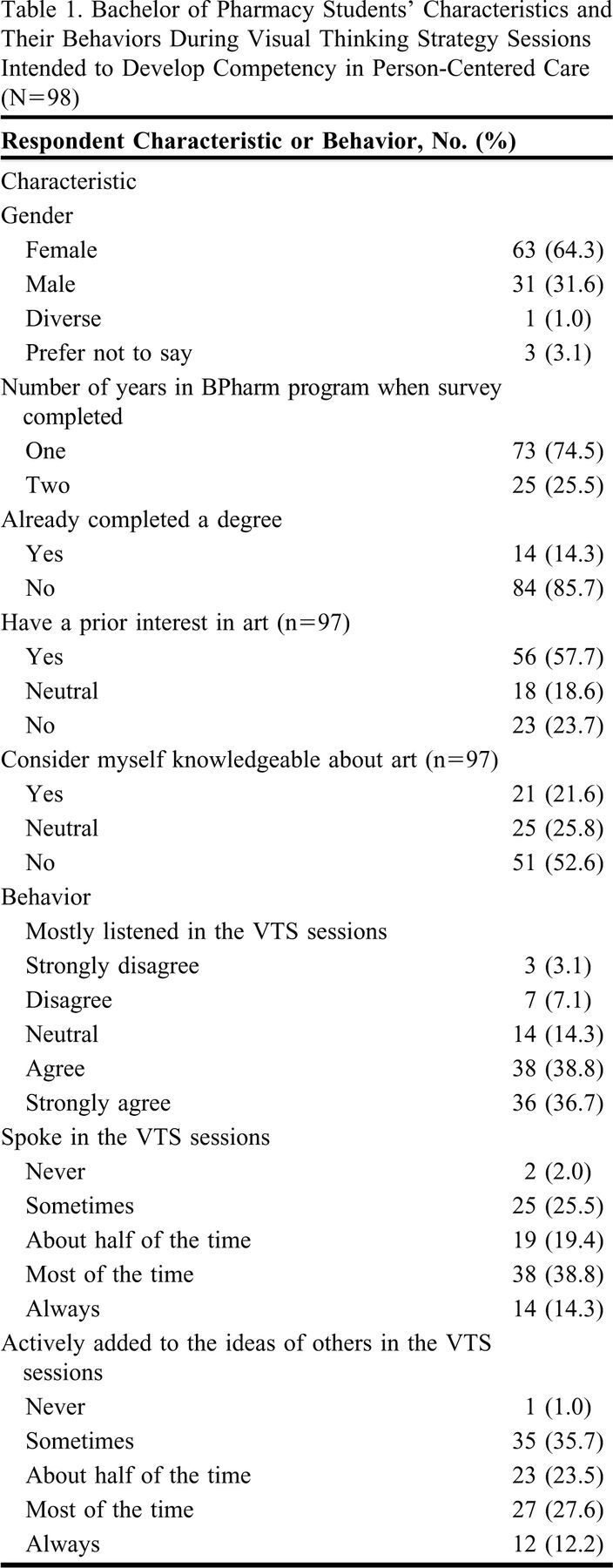

Seventy-four students (75.5%) reported mainly listening in the VTS sessions, 52 (53.1%) spoke in most, or all sessions, and 35 (35.7%) added to the ideas of others in most, or all sessions. Additional details regarding respondents’ characteristics and actions during the VTS sessions are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bachelor of Pharmacy Students’ Characteristics and Their Behaviors During Visual Thinking Strategy Sessions Intended to Develop Competency in Person-Centered Care (N=98)

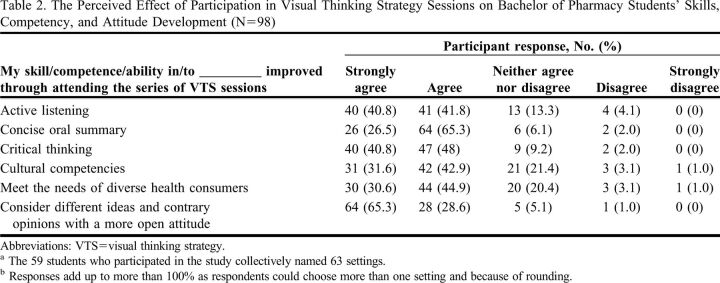

With respect to inclusive practice skills development, students were asked whether they believed that attending VTS sessions had improved specific components of their communication, cultural competence, and critical thinking skills. Participants overwhelmingly agreed that they had, with the lowest level of agreement reported for an item being 74.5%. The frequency distribution of student responses to six questions is provided in Table 2 along with an overview of student-perceived development of skills, competencies, and abilities as a result of participation in VTS sessions.

Table 2.

The Perceived Effect of Participation in Visual Thinking Strategy Sessions on Bachelor of Pharmacy Students’ Skills, Competency, and Attitude Development (N=98)

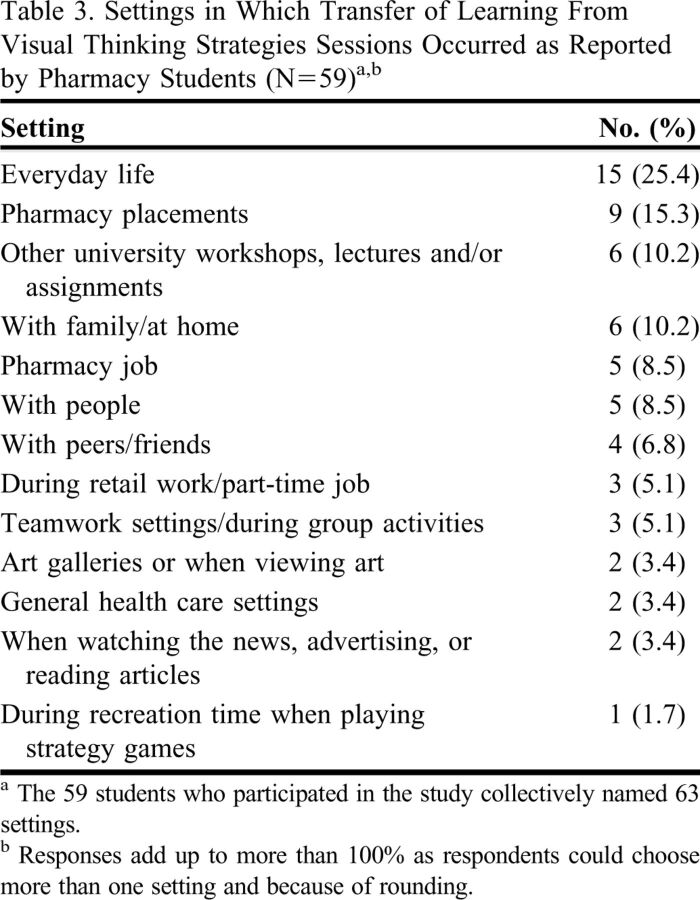

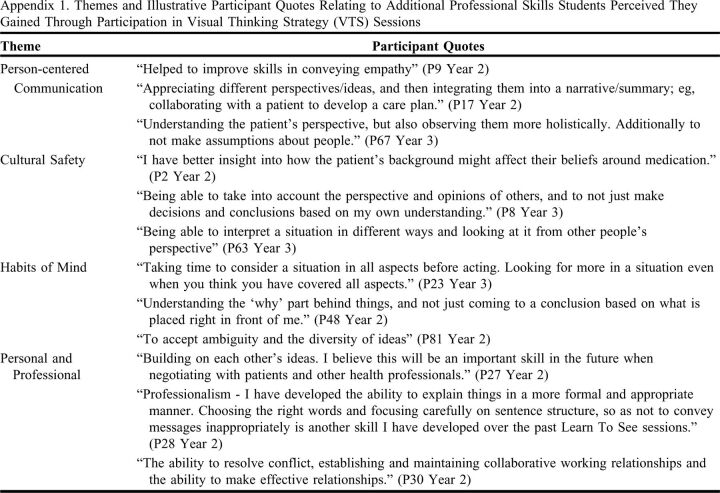

Additional professional skills believed to have been developed or improved through participation in the VTS sessions were explored through an open-text question. Responses were thematically analyzed and subsequently categorized into four broad skill-based themes of person-centered communication, cultural safety, habits of mind, and personal and professional. Illustrative student quotes related to those themes are presented in Appendix 1. With respect to learning transference, 59 (60.2%) students had thought about the VTS questions or used what they had learned in VTS sessions in settings outside of their BPharm clinical and professional skills classes. Open-text responses describing where this knowledge had been applied were categorized into 13 settings, the most frequent being everyday life (n=15) (Table 3). Forty-four (44.9%) students gave examples of where they had thought about the VTS skills or key questions during their placements or in other professional pharmacy practice settings, such as part-time pharmacy jobs.

Table 3.

Settings in Which Transfer of Learning From Visual Thinking Strategies Sessions Occurred as Reported by Pharmacy Students (N=59)a,b

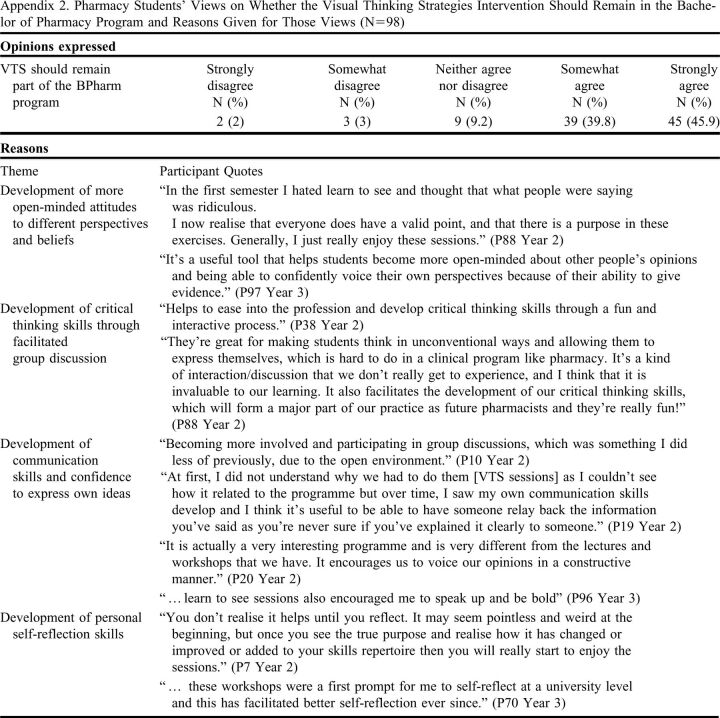

Students were asked for their views on whether VTS sessions should remain part of the BPharm program. Eighty-four students agreed that they should, nine were neutral, and five disagreed. Themes arising from the reasons provided were developing communication skills, including the confidence to communicate, open-mindedness, critical thinking, and self-reflection. The themes with illustrative quotes are presented in Appendix 2. Additionally, some respondents cited the open and accepting environment of the sessions; others wanted the sessions to remain as they were, ie, fun, enjoyable, and/or interesting, and some described students’ change in attitude towards the sessions as the year progressed. Eleven respondents believed there were too many VTS sessions in the year, 81 thought that 10 sessions were “about right,” and six students thought there were too few sessions.

DISCUSSION

We adapted the visual thinking strategy methodology for use with pharmacist trainees and the pharmacy contexts of New Zealand, and to align with the Competence Standards for the Pharmacy Profession in New Zealand.19 This study explored student perceptions of their skills development relating to person-centered care as a result of participation in a series of VTS activities, the transfer of this learning to other settings, and student views on VTS and participating in the sessions. This study was framed around students’ self-evaluation of their VTS work.

The results indicate Visual Thinking Strategy sessions may make a valuable addition to our pharmacy curriculum, offering opportunities for students to integrate learning and transfer skills, knowledge, and attitudes both horizontally and vertically across the curriculum and into settings beyond academia. Student perceptions of the effect of VTS session participation on their skills and attitude development were positive. Students generally believed the sessions supported the development of all the skills and abilities surveyed, reporting a minimum level of agreement with improvement occurring of 74.5%. Three areas were rated particularly strongly with respect to students’ ability to consider different ideas (65.3% strongly agreed), development of critical thinking skills (40.8% strongly agreed), and development of active-listening skills (40.8% strongly agreed).

Advancement of these competencies through VTS has also been reported by others using student self-reports.28,38,39 A 2019 narrative review concluded that, apart from clinical observation skills, evidence for visual image instruction in developing other skills during medical education is poor.40 However, unlike these other single-session interventions, our findings arise from participation in multiple VTS sessions and related activities across an entire academic year. This was deliberate, as Housen’s original VTS studies revealed that repeated sessions were optimal for embedding skills and realizing transference of learning to other situations.23,41 With minimal space available in the curriculum, a series of VTS sessions was incorporated within existing year 2 foundational skills teaching sessions. Naghshineh and colleagues noted a skill-building VTS session “dose” effect with medical students42; Poirier and colleagues reported that participation in a series of 15-minute VTS sessions resulted in pharmacy students making more observations about images.43

A focus on skills and attitudes developed in these sessions could be considered as fostering the “habits of mind” that Costa and Kallick note should be “performed automatically, spontaneously, and without prompting.”44 Achieving this requires regular practice. The beneficial effect of participating in numerous sessions was noted by some of our students who recognized their own initial resistance to the sessions and later their transformed views and attitudes and skills development over time.

A recent review by Mukunda recommends that visual image evaluations should incorporate more rigour.40 Although not presented as data in this study (due to ethical constraints), respondents’ perceptions of their skills growth over the year as a result of applying VTS were consistent with the changes reflected in the students’ written assignments, which were assessed using a validated VTS assessment rubric. The rubric examines elements such as students’ observations, interpretations, evidence provision, and revised opinions.

Having pharmacy students participate in VTS sessions appeared to address the affective domain of learning, which is recognized globally for its importance in helping students manage the emotional contexts and dissonance of interacting with people with diverse views and experiences.22 Similarly, Frei and colleagues used art observation and interpretation with nursing students to develop nuanced understanding of communication, power in relationships, and empathy.45

Additionally, VTS allows the facilitator to model inclusive practices and for participants to experience being listened to, having their views validated, and being asked to justify their viewpoint in an open and non-judgmental manner.39 The consistent process acknowledges different interpretations and encourages students to gain confidence to express their ideas and to actively and respectfully disagree with others.46

Another strength of the VTS method is the flexibility afforded by image selection. We deliberately selected images that would challenge students and tap into the affective domain of learning to align with our own curricular goals and context. However, image selection can be used as a means to focus student learning on other desired learning domains and goals.28

We assert the retention, habitual use, and transference of the skills and attitudes developed by pharmacy students in this study through VTS learning is crucial for the development of inclusive health practitioners. Our findings suggest that pharmacy students’ VTS-acquired learning can be and was transferred to other settings. We believe that modelling being reflective practitioners and the habitual use of the VTS three-question facilitation structure aided pharmacy students in their ability to transfer VTS skills and attitudes to other settings. Students participating in this study agreed that their VTS learning had been used in other areas both in pharmacy and non-pharmacy settings. VTS has been described as a model of engaged discussion where participation is expected.46 To increase learning transference, Caffarella highlights the significance of active learning techniques that include application of knowledge and critical reflection opportunities embedded within this new learning.47 In addition to the active learning that occurs during VTS sessions, transfer of VTS learning was also encouraged through the four-part VTS assignment that required students to reflect on and document the writing of others about an image, changes in their own interpretations of an image, and where their developing skills would be useful in future pharmacy practice. Completing the questionnaire served as a reflection point, hence it was mandatory.

Purposeful reflection is a tool for gaining self-knowledge and insight.48 Mezirow’s assertion that critical self-reflection can lead to transformational learning49 supports our own observations and the central role of self-reflection in professional development is further documented elsewhere in clinical education literature.12 -14,22,29,50

The pharmacy students in this study were overwhelmingly positive regarding the acceptability of participating in the series of art-based VTS sessions, with 86% believing that it should remain in the curriculum despite almost a quarter of study participants indicating no prior interest in art and half self-reporting no art knowledge. While some students appreciated the skills-building aspect of the sessions, other student responses to the assignment included enjoyment, interest, and a break from a “science-only” focus that the sessions provided. Poirier has likewise reported pharmacy student enjoyment of VTS sessions.43

One limitation of this study is that the findings were based on students’ self-reported perceptions of VTS sessions. Additionally, for ethical reasons no control group was used. Data were gathered soon after the completion of the session series for some participants and 12 months post-completion for others. While this resulted in a lower response rate, collecting data 12 months post participation may have given students time for VTS skills to be applied and the significance or insignificance of VTS to be recognized. The response rate was 56%; therefore, responder bias, with or without social desirability bias, could have occurred such that only students with favorable views consented to participate in the study, despite survey responses being de-identified prior to analysis. Also, students may have misattributed their skills growth to VTS when it arose from increasing maturity, other teaching activities, and/or experiences, or that their skills growth resulting from VTS participation was unrecognized.

CONCLUSION

This study adds to the body of literature examining practical methods to develop person-centered practices and transferable competencies in pharmacy students through structuring of divergent, discussion-based, reflective activities in class. Incorporating multiple VTS sessions into year 2 of the BPharm program appears to have been a valuable addition to the curriculum. The sessions are acceptable to students and seem to support the development of key skills and attitudes relating to providing inclusive person-centered care. This incorporates critical thinking, professional skills, and aspects involving the affective domain including communication, cultural safety and self-reflection. Visual thinking strategies also offers opportunities for students to integrate learning from other areas of the curriculum, and students report transference of attitudes and skills to other areas of the curriculum, practice, and their personal lives. Future research will aim to provide further evidence that development of person-centered skills and attitudes can be supported through judicious image selection and priming of students by articulating the overall purpose of VTS in the curriculum and the focus of each session.

Appendix 1.

Themes and Illustrative Participant Quotes Relating to Additional Professional Skills Students Perceived They Gained Through Participation in Visual Thinking Strategy (VTS) Sessions

Appendix 2.

Pharmacy Students’ Views on Whether the Visual Thinking Strategies Intervention Should Remain in the Bachelor of Pharmacy Program and Reasons Given for Those Views (N=98)

REFERENCES

- 1.Ministry of Health. Achieving Equity. Ministry of Health. Accessed 13th March 2022. https://www.health.govt.nz/about-ministry/what-we-do/work-programme-2019-20/achieving-equity

- 2.National Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Health Equity. Accessed 13th March 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/healthequity/index.htm

- 3.Amin-Korim R, Legge D, Gleeson D. PHAA’s Health Equity Policy. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2018;42(5):421-3. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munro A, Boyce T, Marmot M. Sustainable health equity: achieving a net-zero UK. Lancet. 2020;4(12):E551-E553. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30270-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada. Key Health Inequalities in Canada A National Portrait. 2018:437. Accessed 13th March 2022. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/science-research/key-health-inequalities-canada-national-portrait-executive-summary/hir-full-report-eng.pdf

- 6.Health and Disability Commissioner. Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights Regulations 1996. 1996. Accessed 13th March 2022. https://www.hdc.org.nz/your-rights/about-the-code/code-of-health-and-disability-services-consumers-rights/

- 7.Health and Disability System Review. Health and Disability System Review Health and Disability System Review executive overview. 2020:36. Accessed 13th March 2022. https://systemreview.health.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/hdsr/health-disability-system-review-final-report-executive-overview.pdf

- 8.Richardson F. An introduction to inclusive practice. In: Davis J, Birks M, Chapman Y, eds. Inclusive Practice for Health Professionals. Oxford University Press; 2015:2-22:chap 1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smits K. Multiculturalism, Biculturalism, and National Identity in Aotearoa/New Zealand. In: Ashcroft R, Bevir M, eds. Multiculturalism in the British Commonwealth: Comparative Perspectives on Theory and Practice. University of California Press; 2019:104-124. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsden I, Spoonley I. The cultural safety debate in nursing education in Aotearoa. NZ Annl Rev Educ. 1993;3:161-173. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Intl J Equity Health. 2019;18. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haack S. Engaging pharmacy students with diverse patient populations to improve cultural competence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5):Article 124. doi: 10.5688/aj7205124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driscoll J. Practicing Clinical Supervision: A Reflective Approach for Health care Professionals 2nd ed. Balliere Tindall Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schön D. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Temple Smith; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zweber A. Cultural competence in pharmacy practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66:172-176. doi:aj660214.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poirier T, Butler L, Devraj R, Gupchup G, Santanello C, Lynch J. A cultural competency course for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(5):81. doi: 10.5688/aj730581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vyas D, Caligiuri F. Reinforcing cultural competency concepts during introductory pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(7):129. doi: 10.5688/aj7407129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pharmacy Council of New Zealand. Statement on cultural competence 2011:6. Accessed 13th March 2022. http://pharmacycouncil.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Cultural-Competance-statement-2010-web.pdf

- 19.Pharmacy Council of New Zealand. Competence Standards for the Pharmacy Profession. 2015:40. Accessed 13th March 2022. https://pharmacycouncil.org.nz/pharmacist/competence-standards/

- 20.Aspden T, Butler R, Heinrich F, Harwood M, Sheridan J. Identifying key elements of cultural competence to incorporate into a New Zealand undergraduate pharmacy curriculum. Pharm Educ. 2017;17(1):43-54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krathwohl D, Bloom B, Masia B. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals: Handbook II Affective Domain. David McKay Co. Inc; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muzyk A, Lentz K, Green C, Fuller S, May B, Roukema L. Emphasizing Bloom’s affective domain to reduce pharmacy students’ stigmatizing attitudes Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(2):Article 35. doi: 10.5688/ajpe81235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Housen A. Aesthetic thought, critical thinking and transfer. Arts Learning J. 2002;18(1). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piaget J. The Psychology of Intelligence. Routledge; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruner J. Toward a Theory of Instruction. The Harvard University Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klugman CM, Beckmann-Mendez D. One thousand words: evaluating an interdisciplinary art education program. J Nurs Educ. Apr 2015;54(4):220-3. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20150318-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reilly JM, Ring J, Duke L. Visual Thinking Strategies: a new role for art in medical education. Fam Med. Apr 2005;37(4):250-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caffarella R, Barnett B. Characteristics of Adult Learners and Foundations of Experiential Learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. 1994;62:29-42. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernander R. A Literature Summary for Research on the Transfer of Learning. 2018. Accessed 13th March 2022. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/about/documents/A-Literature-Summary-for-Research-on-the-Transfer-of-Learning.pdf

- 31.Harden RM. Ten questions to ask when planning a course or curriculum. Med Educ. 1986;20:356-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones FD. July 7. 1958.

- 33.Kahlo F. Roots. 1943.

- 34.Crewdson G. Daughter. in Twilight: Photographs by Gregory Crewdson: Abrams; 2002.

- 35.Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016;2:8-14. doi: 10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aspden T, Wearn A, Petersen L. Skills by stealth: Developing pharmacist competencies using art. Med Educ. 2020;54(5):442-443. doi: 10.1111/medu.14098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bentwich ME, Gilbey P. More than visual literacy: art and the enhancement of tolerance for ambiguity and empathy. BMC Med Educ. Nov 10 2017;17(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1028-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moorman M, Hensel D, Decker KA, Busby K. Learning outcomes with visual thinking strategies in nursing education. Nurse Educ Today. Apr 2017;51:127-129. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukunda N, Moghbeli N, Rizzo A, Niepold S, Bassett B, DeLisser HM. Visual art instruction in medical education: a narrative review. Review. Med Educ Online. Dec 2019;24(1):1558657. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1558657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Housen A. Methods for Assessing Transfer from an Art-Viewing Program. presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association 2001; Seattle, USA.

- 42.Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intl Med. 2008. 23:991-997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poirier TI, Newman K, Ronald K. An exploratory study using Visual Thinking Strategies to improve undergraduate students’ observational skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(4):Article 7600. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costa AL, Kallick B. Learning and Leading with Habits of Mind: 16 Essential Characteristics for Success. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; 2008.

- 45.Frei J, Alvarez S, Alexander M. Ways of seeing: Using the visual arts in nursing education. J Nurs Educ. 2010;49(12): 672-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nelson A. Visual Thinking Strategies from the museum to the library: Using VTS and art in information literacy instruction. Art Documentation: J Art Libr Soc North Am. 2017;36(2): 281-292. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caffarella R. Devising Transfer-of-Learning Plans. In: Caffarella R, ed. Planning Programs for Adult Learners: A Practical Guide for Educators, Trainers, and Staff Developers (2nd ed). Jossey-Bass; 2002:203-223:chap 10.

- 48.Palmer PJ. The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life. Jossey-Bass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mezirow J. Fostering Critical Thinking in Adulthood: A Guide to Transformative and Emancipator Learning. Jossey-Bass; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boud D, Keogh R, Walker D. Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning. Kogan Page; 1985.