Abstract

Objective. For many pharmacy students in the United Kingdom there are few opportunities during undergraduate education to learn, or be exposed to, different ways of dealing with ethical and professional dilemmas in real life practice. This study aimed to explore the experiences of graduates during their pre-registration year and early practice (up to two years post-qualification) on their perceived preparedness to make professional decisions when faced with problems or dilemmas once in practice.

Method. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with preregistration trainees and early careers pharmacists (up to two years qualified). Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed thematically using the Framework Approach.

Results. Eighteen interviews (nine preregistration trainees and nine qualified pharmacists) were conducted. Four key themes emerged: continued learning in practice, exposure to role-modelling, moral courage, and stress and moral distress.

Conclusion. This study found that preregistration trainees and early career pharmacists perceive a need to be challenged and to receive further support and positive role-modelling to help them continue to develop their ethical and professional decision-making skills in the practice setting. The level and quality of support reported was variable, and there was a reliance on informal networks of peer support in many cases. This study suggests a need to raise awareness among preregistration tutors (preceptors) and line managers (supervisors) to improve and increase support in this area.

Keywords: transition, pharmacy, early practice, role models, peer support

INTRODUCTION

In the United Kingdom, upon completion of an undergraduate Masters of Pharmacy (MPharm) degree, pharmacy graduates undertake a year-long preregistration training period (internship), most often within a single sector (usually hospital or community pharmacy). In contrast to the US system, students have the responsibility of finding their own preregistration experiential placements, and following graduation, the university has no control over the graduate’s final year of training (preregistration year). Preregistration tutors (preceptors) support trainees during this period of their training. Pharmacists who wish to become preregistration tutors must have been practicing within their chosen field for at least three years. The tutor must ensure that their trainee meets required competencies in various standardized tasks before declaring them fit to practice. These competencies are stipulated by the UK General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC), which is the professional regulatory body and licensing board in the United Kingdom. In addition to meeting these competencies, students must pass a national preregistration examination (equivalent to a licensure examination in the United States) at the end of their preregistration year to finally become registered as a pharmacist with the UK GPhC. 1

Unlike many other health care fields, the UK’s Master of Pharmacy (MPharm) degree is funded as a science major and therefore is not eligible for clinical supplements to fund extended placement opportunities. As a result, there are often minimal opportunities for pharmacy students to learn, or be exposed to, different ways of dealing with ethical and professional dilemmas in real life practice. Siegler recommended that instruction in ethics be reinforced by integrating it into medical clerkships (equivalent to placement opportunities) so students could observe ethical dilemmas in context and the ethical behavior and professional conduct of experienced role models. 2 Although individual schools of pharmacy provide opportunities for experiential learning, the amount of training can vary widely across institutions. 3 This means that there is an onus on preregistration tutors to ensure that their trainees further develop ethical and professional decision-making skills during their preregistration year.

Once qualification is achieved, early career pharmacists who practice in hospital pharmacy work within teams and can generally call on others for advice when faced with professional dilemmas. Those working in community pharmacy, however, are often solely responsible for running the pharmacy. Magola and colleagues found that novice community pharmacists newly transitioning into practice were faced with many stress-inducing challenges, with professional decision-making reported as their greatest challenge in early practice. 4

At Keele University School of Pharmacy and Bioengineering (SPhaB) in the United Kingdom, we conducted a study to explore the experiences of graduates during their preregistration year and early practice (up to two years post qualification). Specifically, views were sought on their perceived preparedness to make professional decisions when faced with problems or dilemmas in practice. This was part of a larger project studying the impact of teaching ethics and professional decision-making in the MPharm undergraduate degree.

METHODS

A qualitative approach was chosen to explore the in-depth views of interviewees. Interviews were favored over focus groups as sensitive issues could potentially be discussed. All UK-based alumni from Keele University who were either preregistration trainees or early career pharmacists (up to two years qualified) were invited to participate, either via a question at the end of a survey, or (for a small number of preregistration trainees) during a final undergraduate teaching session. The aim was to achieve a purposive sample with a mix of male and female interviewees, and both trainees and early career pharmacists of varying ethnicities working in hospital and community pharmacy. Interviews were conducted from May through June 2015, and from January through March 2016 at times and places convenient to the interviewees. This enabled data saturation to be reached whereby additional data obtained did not reveal any new insights or information related to the broad topics of interest in the interview guide. 5

An interview schedule was developed based on a literature review and the aims of the study (Appendix 1). It addressed interviewees’ views on teaching and learning ethics and professional decision-making at Keele University SPhaB (not reported here) and their views on transitioning to professional practice. The schedule was assessed by an experienced researcher for face validity and some rephrasing was made to avoid leading questions. 6 The interview schedule was used as a guide to ensure all topics were covered but was not adhered to so rigidly that conversation could not flow freely. Qualitative interviews are an iterative process; thus, the first three interviews yielded rich data with no substantive changes made to questions, so these were included in the final analysis.

Participant information sheets were emailed in advance, and once the interviews were arranged, interviewees were invited to ask any further questions prior to the interview commencing. Participants signed a consent form before starting, and the interview was audio-recorded. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed thematically using the Framework Approach. 7 This involved seven stages: transcription, familiarization, coding, developing a framework, applying a framework, charting the data, and interpreting the data. 8 Two of the authors independently coded the first three interviews. A coding framework was agreed upon and subsequently applied to the rest of the transcripts. Because the aim of the project was not specifically to compare preregistration trainees to early career pharmacists but to gauge views from alumni who have not long graduated, all 18 participants were analyzed together. Where the preregistration trainees and pharmacists clearly differed is reported below. Approval for the study was received from the Keele University Research Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

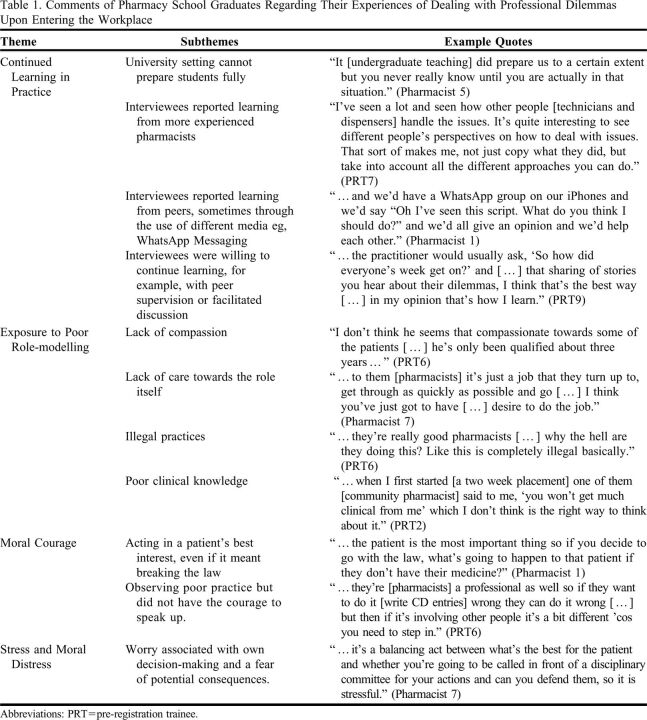

Eighteen semi-structured interviews were conducted, ranging from 50 minutes to 2 hours, with 18 interviewees. There were nine pharmacists and nine preregistration trainees. Thirteen of the 18 participants were female and 10 were Caucasian. Thirteen of the participants worked in community pharmacies and five worked in hospital pharmacies. Four main themes emerged from the interviews: continued learning in practice, exposure to role-modelling, need for moral courage, and stress and moral distress. These are discussed below, with additional exemplar quotes presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comments of Pharmacy School Graduates Regarding Their Experiences of Dealing with Professional Dilemmas Upon Entering the Workplace

Given the myriad of professional and ethical dilemmas that could potentially occur in practice, interviewees acknowledged that it would be impossible to prepare fully for every eventuality, and that there were limitations on what could be achieved at the undergraduate level. Interviewees, therefore, recognized a need for ongoing support around professional decision-making, particularly during the preregistration year and when first qualified. They reported, however, that they had continued to learn from others during their time in practice. Interviewees reported learning from a range of people within their organization, including from their preregistration tutors and senior staff (managers and superintendents), as well as by accessing support services, for example, a governance department within their organization’s head office.

Four preregistration trainees and two pharmacists reported that they referred to their preregistration tutor as a source of advice, usually to discuss and reflect on problems. Preregistration trainee 1 remembered asking for a more in-depth analysis of her preregistration tutor’s decision-making, stating: “I’ve asked him about things, sort of saying, ‘how do you make decisions? What’s your rationale?’” Not all interviewees had such in-depth interactions, however, and reported they had simply learned through observation. Preregistration trainee 7 described how he formed his own way of dealing with problems after working with a range of staff, including pharmacy “locums” who are contracted to provide temporary cover for the regular pharmacist. Through observation, he was able to identify strategies that worked well for other pharmacists faced with difficult dilemmas in practice.

Although interviewees reported that the majority of further learning around decision-making tended to be learning from those around them, they also identified their peers as a valuable source of support. Four interviewees reported contacting former friends from university for advice via WhatsApp messaging groups, either while in the midst of a difficult dilemma or when reflecting on a past problem. Peer supervision was also reported to be a valuable learning tool. Pharmacist 9 reported participating in formalized peer supervision sessions within his organization, finding that peers were much more confident to talk about dilemmas among themselves than with senior staff. Similarly, during monthly preregistration development days, preregistration trainees had the opportunity to discuss problems together, facilitated by a pharmacist.

When interviewees were asked specifically about role models, several said they had observed negative role models in practice much more often than they observed positive ones. Positive role models were perceived to be good communicators, respectful to colleagues, and able to provide good advice. Some referred to their preregistration tutor as a helpful, positive influence and aspired to be like them, but not all. There were many variations of negative role models observed in practice. Interviewees reported unprofessional attitudes and behaviors in some pharmacists towards both colleagues and patients, for example, lack of compassion or lack of caring about their role as a health care provider. Observations of illegal practices were also mentioned. For example, pre-registration trainee 6 was shocked to see controlled drugs being dispensed without a valid prescription. Another aspect of negative role-modelling related to pharmacists either not challenging a doctor or backing down too easily. Preregistration trainee 2 perceived that even some experienced pharmacists lacked confidence in their role, while other pharmacists had poor knowledge of clinical or legal issues.

Trainees and pharmacists must have the courage to do the right thing when faced with suboptimal practice or difficult decisions. Moral courage is the courage to speak up or act for what you believe to be morally right, despite fear of potential consequences for doing so. 9 Thus, a sign of preparedness for practice among the interviewees was a willingness to challenge rules and regulations to ensure that the best interests of patients were met. Although they understood right from wrong in terms of the law, pharmacists in this study were more willing than trainees to make choices contrary to the law which they felt were morally right. In doing so they were demonstrating moral courage as they were leaving themselves vulnerable to retribution, either from the GPhC or their employing organization (or both). Courage was also demonstrated by ensuring work was undertaken within legal boundaries in pharmacies where poor practice was the cultural norm. For example, while working as a locum pharmacist, pharmacist 6 had the courage to stand up to an aggressive patient and dispensary staff members who were pressurising her to dispense an unsigned prescription.

Not all interviewees felt they could challenge all issues relating to poor practice. This was observed among preregistration trainees in particular, where four of nine reported that they would not challenge a qualified pharmacist. Preregistration trainee 6, for example, found it difficult to challenge experienced pharmacists who were not following legal requirements for controlled drug register entries. However, he seemed to have set his own standards. Despite not challenging pharmacists who made legal errors, he stated that he would challenge decisions that affected patient care.

Moral distress has been defined as “the experience of psychological distress that results from engaging in, or failing to prevent, decisions or behaviours that transgress, or come to transgress, personally held moral or ethical beliefs.” 10 There were a few situations described by interviewees that could have potentially contributed to moral distress, including inequity of service and dilemmas around commercial concerns. For example, pharmacist 2 was left feeling “conflicted” when asked by a senior manager to falsify in-house records for the pharmacy to meet a weekly Medicines Use Review (MUR) target an MUR is a consultation with the patient regarding their adherence to taking their prescribed medications). She agreed, justifying her decision by stating that there was “…an honest intention” to complete the five MURs. On reflection she felt that she “made the right decision for the shop,” demonstrating company loyalty, but wondered at what expense to her own moral values.

The examples given by interviewees of stressful feelings were most often related to fear of the consequences of breaking the law. They therefore acted in congruence with their personal moral values but experienced stress because of doing so. Interviewees worried about the potential consequences that a poor decision might have on their career. They articulated this by referring to a fear of legal consequences, regulatory sanctions by the GPhC, or retribution by their employer. Legal and procedural concerns were evident throughout the interviews, but in most cases were balanced with a caring, patient-centred approach.

DISCUSSION

Although interviewees reported that teaching received at university regarding ethical and professional decision-making had been beneficial, they still required further support in this area when transitioning to practice. They talked about learning mostly from observing staff around them, or sometimes through ethical or professional discourse; however, this was not the norm. They learned what to do by observing positive role-models, but they also learned what not to do by observing negative role-models. Interviewees reported valuing peer supervision, as well as supporting and learning from each other through informal networks. When faced with professional and/or ethical dilemmas in practice, the pharmacists interviewed tended to demonstrate moral courage, whereas preregistration trainees were more reticent. Most interviewees reported feelings of stress related to the potential consequences of their decisions, particularly those who had been willing to break the law. However, they still reported having a person-centered and caring approach towards patients. Countries in which the university has input into the experiential learning experiences of students postgraduation (such as the United States), may have more opportunities to address these issues pre-licensure. Similarly, the United Kingdom will align more closely with the US system when newly introduced changes to the format of the UK pharmacy degree are enacted. 11

The hidden curriculum refers to the socialization process through which values and norms are transmitted from pharmacy educators to students; this “hidden” content can often be at variance with what is taught explicitly. 12 Pharmacy students learn most of the professional values, attitudes, beliefs, and related behaviors implicitly through this “hidden curriculum’ rather than through explicit formal teaching, and do so in part by observing role models and their positive and negative attributes. Role models can, therefore, play a vital part in preparing pharmacy students and preregistration trainees for practice. In fact, some educators have argued that role-modelling is highly influential and the most important strategy for improving professionalism among pharmacy students. 13 Observing positive role models was recognized in this study as a learning opportunity on how to deal with dilemmas in practice. According to Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory (1982), vicarious experiences of observing role models succeed in their endeavours raises our own self-belief that we too can succeed. 14 Having positive role models to learn from in practice, therefore, is important in supporting preregistration trainees and early career pharmacists to develop confidence and belief in their ability to make sound, justifiable ethical and professional decisions in practice.

Bandura also proposed that the most effective way to develop confidence (or self-efficacy) is to gain mastery of the task. 14 The more opportunities individuals have to experience and cope effectively with dilemmas, the greater their self-belief will be that they can deal competently with future problems. In theory, therefore, those transitioning through preregistration training and early practice would benefit from being challenged often (in a supportive environment). When considering the preregistration training year, this would require the preregistration instructor to undertake a proactive role in questioning, challenging, and partaking in ethical discourse with their trainees about the professional dilemmas they are facing. This study suggests that this in-depth interaction is not commonplace. There is room therefore to raise awareness of this need among preregistration tutors, and to support them in developing this aspect of their role. In addition, increasing placement duration and frequency during pharmacy undergraduate years should increase the opportunities for students to observe and even experience professional problems or dilemmas in real life, and would benefit from seeing how they are resolved in practice.

Although pharmacy preregistration tutors have been identified previously as strong role models, some tutors and other experienced pharmacists were associated with more negative connotations in this study. 15 Negative role models have also been identified across other health care professions in both clinical and classroom settings. 16, 17 Recommendations on how to counteract the potentially negative effects of the hidden curriculum have included having frank dialogue with students about real life experiences and the challenges they present to professional ideals. 12 Raising awareness of the positive and negative effects that role-modelling could have on an undergraduate students’ own professional development could also increase their resilience so that they are better prepared when faced with it in practice. 18

Having the opportunity to discuss experiences of ethical and professional dilemmas was important to some interviewees who had learned from peers within their organization, either formally or informally, by discussing the dilemmas to which they had been exposed. Social media has a positive role to play as a platform for informal networks of support among trainees and early career pharmacists. Interviewees reported asking for advice and sharing their own experiences in this way, finding it a valuable tool. In the United Kingdom, some organized peer support networks are available. In theory, peer discussion provides an opportunity for deliberation on real life ethical cases, which is fundamental to developing skills in decision-making. 19, 20 This opportunity for peer discussion or “peer supervision” forms the basis of a more formalized approach to developing person-centred care within some organizations. Known as Schwartz rounds, professionals in an organization explore a workplace event such as a patient case, moderated by a trained facilitator. This allows staff time to reflect and share insights. Reported benefits include increased empathy and greater ability among staff to handle sensitive issues. 21 The use of a trained facilitator may not be a viable option for many, but the principles of reflecting and sharing insights can be applied in any setting.

Pharmacists and preregistration trainees need to have the moral courage to deal effectively with, and act on, ethical or professional dilemmas in practice. The nursing literature in particular has addressed the issue of moral courage in the workplace in recent years, 22, 23 but literature relating specifically to moral courage among pharmacy professionals is limited. Moral courage relates to Rest’s Four Component Model of Morality, a model of key components that are believed to be important for effective moral functioning in health professionals. 24 It has, as its final element, moral character, ie, being able to construct and have the moral courage to implement an action. In this study, pharmacists reported experiences where they displayed the courage to do what was in the best interests of their patients, acting in accordance with their own moral values, despite being fearful of possible consequences. Most preregistration trainees reported acting ethically themselves but were less willing at times to put the patient before the law or to speak up against observed poor practice. This reported difference was possibly due to preregistration trainees’ limited experience in practice, combined with a lack of confidence in their own decision-making ability. Strategies have been proposed to develop moral courage, including training in cognitive strategies on how to deal with highly emotive situations, and training in assertiveness and negotiation skills to cope with hostility or defensiveness in others. This training could be included within the pharmacy undergraduate curricula. 25

Although prevalent in nursing literature since the 1980s, 26 the concept of moral distress did not appear in the pharmacy literature until 2004 in a paper by Kalvemark and colleagues. 27 Traditionally, moral distress has been defined as stress occurring when a person experiences ethical dilemmas and is thought to result from institutional constraints, but the definition is much broader now. 28 Initially, moral distress causes anger and anxiety, but longer term has been associated with feelings of guilt and hopelessness, and loss of confidence and self-esteem among other symptoms. 29 It has also been linked to burnout and mooted as a reason for leaving a profession. In this study, fear of consequences of breaking the law, or distress caused by not breaking the law when it was deemed the most ethical option, was reported among early career pharmacists and pre-registration trainees alike. Some interviewees worried about the potential consequences that a poor decision might have on their future career. Similar findings have been reported by pharmacists in international studies. 30, 31 In the United Kingdom, Astbury and Gallagher measured levels of moral distress experienced among community pharmacists, and found that moral distress was more frequent and intense among newly qualified pharmacists than among their more experienced colleagues. 32 Moral distress must be seen within the context of ethical dilemmas and not separate from them. 33 This means that the focus should not solely be on the individual to be able to make a well-reasoned judgement. Organizational changes, for example, adequate staffing levels and the culture within the organization may need to be addressed to create an environment in which early career pharmacists and preregistration trainees feel empowered to take an ethical course of action.

A key message from this study is that interviewees reported the need for ongoing support around professional and ethical decision-making during both the pre-registration year and early practice. This finding aligns with a study by Magola and colleagues which reported community pharmacists (qualified up to three years) find professional decision-making to be their greatest challenge, with many also lacking confidence. 4 A requirement for further training of tutors undertaking experiential learning with undergraduate students in the United Kingdom has also been highlighted. 3 This training could include support for pharmacists to undertake ethical discourse with students regarding professional problems faced in practice.

This in-depth study provides data on the experiences and views of a range of preregistration and early careers pharmacists across the United Kingdom, in both hospital and community pharmacy. The opportunity to undertake experiential education varies between countries. For example, in the United States, greater exposure to practice during the Doctor of Pharmacy degree may equate to greater exposure to professional dilemmas prior to qualification. As an insider researcher, MA both taught and conducted the research on professionalism; there was therefore a potential for social desirability bias. 34 A reflexive approach was therefore applied throughout. Having an insider researcher involved in the study also had its benefits, eg, being known and trusted by the interviewees allowed for sensitive subjects to be openly addressed. In this study only the views of pre-registration trainees and early career pharmacists were addressed. Future studies could garner views of preregistration tutors and other staff on the capability of trainees and newly qualified pharmacists. Furthermore, studies could be undertaken to gain in-depth views of pre-registration tutors regarding their own perceived needs around developing professional decision-making skills in others.

CONCLUSION

This study found a perceived need for further support, challenge, and positive role-modelling to assist preregistration trainees and early career pharmacists in the United Kingdom to continue to develop their ethical and professional decision-making skills in the practice setting. The level and quality of support the participants reported varied, and in many cases, they relied on informal networks of peer support. This study suggests a need to raise awareness among preregistration tutors and line managers to improve and increase support in this area; this could potentially require upskilling of experienced pharmacists on ethical discourse to fulfill this role.

Appendix 1. Interview Questions Regarding Pharmacy Graduates’ Preparedness for Practice

How prepared do you currently feel to deal with ethical dilemmas in practice?

How does this compare with how you felt when you graduated and started your pre-reg year?

In hindsight, how well or not do you feel your undergraduate years prepared you for dealing with ethical dilemmas in practice?

How did you get to feel as prepared as you do now?

REFERENCES

- 1.General Pharmaceutical Council. Pharmacist foundation training scheme. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/education/preregistration-training-before-2021

- 2.Siegler M. Training doctors for professionalism: some lessons from teaching clinical medical ethics. Mt Sinai J Med. 2002;69(6):404-409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacob SA, Boyter A. Experiential learning in MPharm programmes: a survey of UK universities. Poster presented at: Pharmacy Education Conference; June 2019; Manchester.

- 4.Magola E, Willis SC, Schafheutle EI. Community pharmacists at transition to independent practice: isolated, unsupported, and stressed. Health Soc Care Comm. 2018;26(6):849-859. 10.1111/hsc.12596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis . London: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sim J, Wright C. Research in Health Care: Concepts, Designs and Methods. Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritchie J, Lewis J, McNaughton Nicholls C, Ormston R. Qualitative research practice. 2nd ed. Sage Publications Ltd: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research, BMC Med Res Methodol . 2013;13:117-24. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/13/117. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kritek PB. Reflections on moral courage, Nurs Sci Quart . 2017;30(3):218-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crane MF, Bayl-Smith P, Cartmill J. A recommendation for expanding the definition of moral distress experienced in the workplace. Aust N Z J Organ Psychol . 2013;6:e1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.General Pharmaceutical Council. Standards for the initial education and training of pharmacists. January 2021. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/standards-for-the-initial-education-and-training-of-pharmacists-january-2021.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- 12.Mahood SC. Medical education. Beware the hidden curriculum, Can Fam Physician . 2011;57:983-985. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3173411/pdf/0570983.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2022. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammer D. Improving student professionalism during experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandura A. (1982) Self-efficacy mechanisms in human agency, Am Psychol . 1982;37:122-147. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122. Accessed June 13, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jee SD, Schafheutle EI, Noyce PR. Exploring the process of professional socialisation and development during pharmacy pre-registration training in England. Int J Pharm Pract . 2016;24: 283-293. 10.1111/ijpp.12250. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baernstein A, Amies Oelschlager AME, Chang TA, Wenrich MD. Learning professionalism: perspectives of pre-clinical medical students, Acad Med. 2009;84(5):574-581. 10.1097/acm.0b013e31819f5f60. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jack K, Hamshire C, Chambers A. The influence of role models in undergraduate nurse education. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(23-24):4707-4715. 10.1111/jocn.13822. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopkins L, Saciragic L, Kim J and Posner G. The hidden curriculum. Exposing the unintended lessons of medical education. Cureus. 2016:8(10):e845. doi: 10.7759/cureus.845. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habermas J. Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action. The MIT Press: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin Books: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Health Foundation. Person-centred care made simple. What everyone should know about person-centred care. January 2016. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/PersonCentredCareMadeSimple.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- 22.Gallagher A. Moral distress and moral courage in everyday nursing practice. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16(2):1-8. https://search.proquest.com/openview/5cc064b115db6db1505b3c2050c2251b/1?pqorigsite=gscholar&cbl=43860. Accessed June 13, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edmonson C. Moral Courage and the nurse leader. Online J Issues Nurs. 2010;15(3):Manuscript 5. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No03Man05. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rest JR. Morality. In Mussen PH, ed. Manual of child psychology. 4th edition. Wiley;1983:495-555. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lachman VD. Strategies Necessary for Moral Courage. Online J Issues Nurs. 2010;15(3):Manuscript 3. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No03Man03. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jameton A. Nursing Practice the Ethical Issues . Prentice Hall Inc: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalvemark S, Hoglund AT, Hansson MG, Westerholm P, Arnetz B. Living with conflicts-ethical dilemmas and moral distress in the health care system. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1075-1084. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00279-X. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crane MF, Bayl-Smith P, Cartmill J. A recommendation for expanding the definition of moral distress experienced in the workplace. Australas J Organ Psychol. 2013;6:e1. doi: 10.1017/orp.2013.1. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burston AS, Tuckett AG. Moral distress in nursing: contributing factors, outcomes and interventions, Nurs Ethics. 2013;20(3):312–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hadad AM. Ethical problems in pharmacy practice: a survey of difficulty and incidence, Am J Pharm Educ. Spring 1991;55(1):1-6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaar B, Brien J, Krass I. Professional ethics in pharmacy: the Australian experience. Int J Pharm Pract. 2005;13(3):195-204. 10.1211/ijpp.13.3.0005. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Astbury JL, Gallagher CT. Moral distress among community pharmacists: causes and achievable remedies. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2020;16(3):321-328. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.05.019. Accessed June 13, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalvemark Sporrong S, Hoglund AT, Arnetz B. Measuring moral distress in pharmacy and clinical practice. Nurs Ethics. 2006:13(4):416-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drake P, Heath L. Practitioner research at doctoral level: Developing coherent research methodologies . Routledge: 2011. [Google Scholar]