Death is a common denominator of the human experience and, therefore, of the health care experience. The advent of modern medicine has brought significant changes to how and where we die. Compared to just a hundred years ago when a majority of individuals died at home, an estimated 30% of Americans died in an intensive care unit (ICU), and end of life costs in the United States now exceed $200 billion annually. 1, 2 Therefore, practicing in critical care (or any discipline of medicine) inevitably brings clinicians and educators in touch with death and dying. This reality has been especially true in the COVID-19 pandemic, during which clinicians have experienced death in unprecedented volume and under especially traumatic circumstances. 3, 4 Unpredictable clinical courses, sudden decompensations, and the absence of family members and loved ones as patients suffer and die alone have become the hallmarks of ICU care. If not provided with the necessary support and coping skills, these experiences may lead to student and resident clinicians having feelings of guilt, resentment, and regret that affect them in unseen ways, ranging from burnout to depression and posttraumatic stress. 5-7 Beyond the direct consequences for clinicians and trainees, these effects can have meaningful ramifications for patient safety. 8 Here, we posit that end-of-life discussions should be foundational to any ICU learning experience and then propose a model for these discussions.

Over the last decade, the profession of pharmacy has placed significant emphasis on involvement of the pharmacist in direct patient care. 9 This emphasis more consistently positions a pharmacist at the bedside, where they are involved in interprofessional decision making as the pharmacotherapy expert. While the presence of the bedside pharmacist has increased dramatically, associated curricular changes in the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum have been slower to develop, especially in the discipline of critical care. In 1987, 38% of pharmacy programs reported offering no education related to death and dying or end-of-life care, as opposed to only 4% and 5% of medical and nursing programs, respectively. 10 While these statistics have improved, as of 2012, 20% of pharmacy programs surveyed still lacked any formal preparation for end-of-life care, and programs that do offer this training provide an average of less than seven hours throughout the entire curriculum. 11 These findings are despite the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards that focus on providing “patient-centered collaborative care” across the patient’s lifespan. 12 Notably, residency training standards have no recommendations regarding this topic. As such, the reality is that pharmacy trainees will face death and related events in their clinical experiences and postgraduate training, and for many, it will be their first experience with death and dying. 13

A pharmacy student’s first experience with death is often the most memorable and emotional, even if they did not have a strong connection with the patient. 14 Similarly, most pharmacy residents are not emotionally prepared to face end-of-life situations or other highly emotional experiences without appropriate guidance and support. 15 Including more end-of-life exposure and training for students in the pre-clinical curriculum may alleviate some of the stressors associated with death and dying; indeed, classroom interventions have been shown to impact empathy and student perceptions of death and dying, 16, 17 and hands-on simulations may be even more effective in preparing students to deal with end-of-life situations. 13, 18, 19 However, evidence suggests that pre-clinical classroom preparation may not have a long-term impact on students. 20 For this reason, the role of preceptors, program directors, and peers, as well as institutional culture in the clinical environment, are paramount for developing practice-ready pharmacists with effective coping skills who are capable of reconciling empathy and professionalism in end-of-life settings. Preceptors must have the necessary skills and comfort level to have crucial conversations with students and residents surrounding end-of-life care.

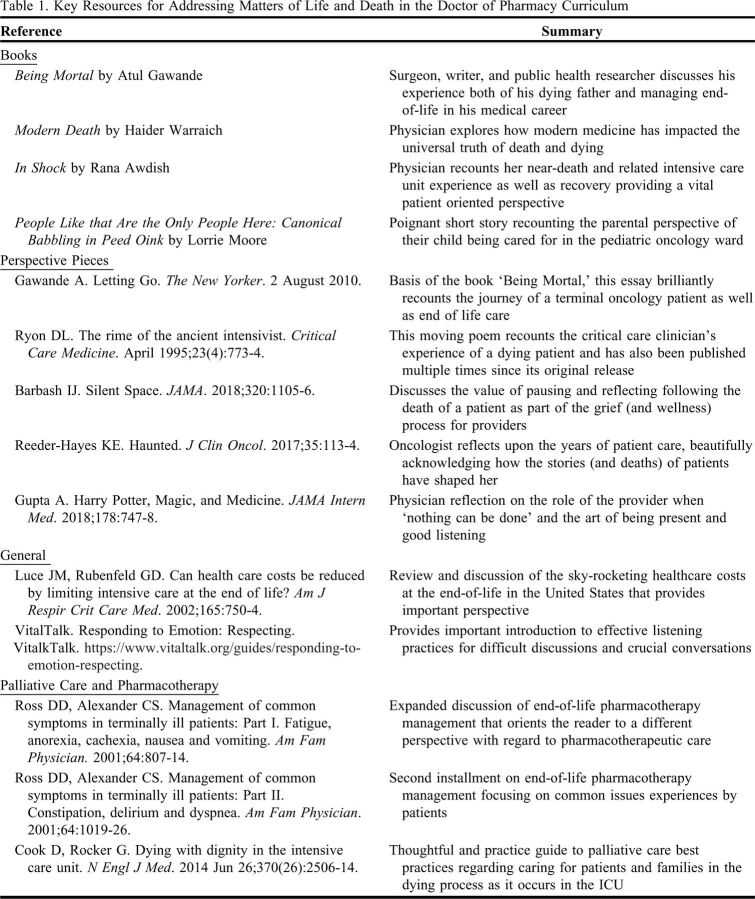

The support and guidance that students and residents receive mostly takes the form of informal one-on-one discussions with preceptors and residency program directors. 15 Given prevailing trends in the US health care system and pharmacy students’ IPPE and APPE requirements, most pharmacy students and residents will have their first exposure to end-of-life care in an ICU setting. Unfortunately, the effects of working in an ICU environment are manifold, including that providers have significantly higher rates of burnout, which has ramifications both for adverse patient outcomes and individual wellness. 21 This burnout and resulting emotional detachment is reflected in the “hidden curriculum” that learners are exposed to in ICU practice areas. (The “hidden curriculum” is the values, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that students learn through their daily interaction with health care providers and how they learn what the medical community thinks is important to being a doctor. 14) Pervasive burnout and emotional exhaustion may affect the way that superiors and role models respond to end-of-life situations and this makes it more difficult for them to sympathize and connect with learners having a “new” experience with death. This culture may lead to a perceived lack of support at a time that is critical for shaping the future attitudes, emotional responses, and coping skills of learners. Indeed, while emotional stoicism is often prized in ICU culture, this coping strategy is counterproductive and can lead to internal conflict for students and residents struggling to reconcile the need to have empathy for their patients with the perceived need for emotional detachment from traumatic situations. 14, 22-25 The ability for a preceptor to guide learners through meaningful discussions and to effectively manage these complex and often difficult scenarios involving end-of-life is an essential skill and can add great meaning to an experiential rotation. 26 Without these discussions and appropriate modeling, highly emotional experiences often lead to the adoption of coping strategies that are detrimental to long-term well-being and a conflicted professional identity. A brief summary of some suggested background resources to support these discussions is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Resources for Addressing Matters of Life and Death in the Doctor of Pharmacy Curriculum

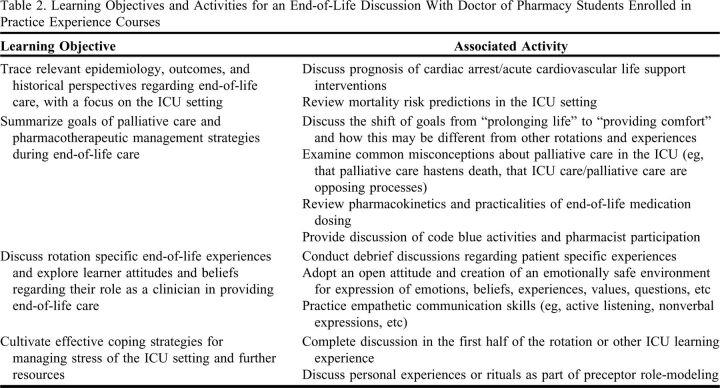

Building on Wilsey’s call for debrief discussions, Ku beautifully summarizes how to handle these sessions and model empathetic communication skills. 27, 28 She emphasizes “timely and consistent debriefing” with three core components: model grief and emotional response, focus on the emotional aspects of the death and dying process rather than just the medical or scientific aspects of the patient case, and discuss strategies and resources for coping with grief. However, we emphasize going beyond these more reactionary discussions to a proactive and structured approach in which preceptors would set aside not only time for debrief discussions but normalize and standardize this topic for every learning experience. Although this topic must be adapted to the specific nature of the practice experience and the learner, we propose a construct that entails establishing overall perspective with the learner (eg, epidemiology and historical viewpoints of end of life), summarizing pharmacotherapeutic goals and strategies in line with “I will use those regimens which will benefit my patients according to my greatest ability and judgment, and I will do no harm or injustice to them.” Finally, the preceptor should allow students time to debrief from the emotionally taxing environment of the ICU and then open a discussion about effective coping strategies that maximize wellness and minimize burnout. While limited data are available regarding optimal strategies for educating pharmacy learners on this important topic, we have provided suggested learning objectives and activities for these discussions in Table 2.

Table 2.

Learning Objectives and Activities for an End-of-Life Discussion With Doctor of Pharmacy Students Enrolled in Practice Experience Courses

Further, integrating concepts of palliative care and associated pharmacotherapeutic management into these end-of-life discussions can provide valuable perspective. The goal of palliative care is to “maintain and improve the quality of life of all patients and their families during any stage of life-threatening illness” by aiming to “prevent and relieve suffering by early identification, assessment, and treatment of physical and psychological symptoms, as well as emotional, and spiritual distress.” 29 As such, intensive care medicine and palliative care are ideally integrated and complementary approaches with benefits for patients, caregivers, and critical care clinicians alike. 30 Notably, palliative care is associated with higher ratings from the patient and their family regarding the patient’s quality of life, death, and end-of-life care, as well as greater wellbeing for their loved ones after the patient dies. 31, 32 Incorporating these elements can underscore the important role of the pharmacist in end-of-life and palliative care, both with optimizing pharmacotherapy and developing end-of-life protocols. 33, 34

Overall, patient-centered management of end-of-life is a necessary competency for graduating clinicians. Educators and preceptors can guide their trainees through this topic using a combination of discussion-oriented knowledge transfer, empathetic listening and deliberate debriefing, and provision of further resources. Indeed, taking time to have these vital end-of-life discussions may serve to help educators model what Hippocrates said: “Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Sikora received funding for this research through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

REFERENCES

- 1.Rothman DJ. Where we die. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2457-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luce JM, Rubenfeld GD. Can health care costs be reduced by limiting intensive care at the end of life? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:750-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakam GK, Montgomery JR, Biesterveld BE, Brown CS. Not dying alone – mondern compassionate care in the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenbaum L. Harnessing our humanity – how Washington’s health care workers have risen to the pandemic challenge. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2069-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leiter RE. Reentry. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):e141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro J, McDonald TB. Supporting clinicians during COVID-19 and beyond – learning from past failures and envisioining new strategies. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):e142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeForest A. The new stability. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(18):1708-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia CL, Abreu LC, Ramos JL, et al. Influence of burnout on patient safety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;30(55):553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. The consensus of the Pharmacy Practice Model Summit. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2011;68:1146-1152.21642579 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickinson GE, Sumner ED, Durand RP. Death education in US professional colleges: medical, nursing, and pharmacy. Death Stud. 1987;11(1):57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson GE. End-of-life and palliative care education in US pharmacy schools. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(6): 532-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ACPE Accreditation Standards. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pharmd-program-accreditation/. (accessed 6 March 2021.)

- 13.Gilliland I, Frei BL, McNeill J, Stovall J. Use of high-fidelity simulation to teach end-of-life care to pharmacy students in an interdisciplinary course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(4):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes-Kropf J, Carmody SS, Seltzer D, Redinbaugh E, Gadmer N, Block SD, Arnold RM. “This is just too awful; I can’t believe I experienced that…”: medical students’ reactions to their “most memorable” patient death. Acad Med. 2005;80(7):634-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pileggi DJ, Fugit A, Romanelli F, Winstead PS, Lawson A, Deep KS, Cook AM. Pharmacy residents’ preparedness for the emotional challenges of patient care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015; 72(17):1475-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manolakis ML, Olin JL, Thornton PL, Dolder CR, Hanrahan C. A module on death and dying to develop empathy in student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beall JW, Broeseker AE. Pharmacy students’ attitudes towards death and end-of-life care. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(6):104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gannon J, Motycka C, Egelund E, Kraemer DF, Smith WT, Solomon K. Teachign end-of-life care using interprofessional simulation. J Nurs Educ. 2017;56(4):205-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egelund EF, Gannon J, Motycka C, Smith WT, Kraemer DF, Solomon KH. A simulated approach to fostering competency in end-of-life care among pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(4):6904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lor KB, Truong JT, IP EJ, Barnett MJ. A randomized prospective study on outcomes of an empathy intervention among second-year student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(2):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerlin MP, McPeake J, Mikkelsen ME. Burnout and Joy in the Profession of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care. 2020;24:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly E, Nisker J. Medical students’ first clinical exerperiences of death. Med Educ. 2010;44(4):421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trivate T, Dennis AA, Sholl S, Wilkinson T. Learning and coping through reflection: exploring patient death experiences of medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho CY, Kow CS, Chia CHJ, et al. The impact of death and dying on the personhood of medical students: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith-Han K, Martyn H, Barrett A, Nicholson H. “That’s not what you expect to do as a doctor, you know, you don’t expect your patients to die.” Death as a learning experience for undergraduate medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson WG, Williams JE, Bost JE, Barnard D. Exposure to death is associated with positive attitudes and higher knowledge about end-of-life care in graduating medical students. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1227-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilsey HA. An Important lesson: Dealing with Death. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2019.. https://cptlpulses.com/2019/02/19/dealingwithdeath/ (accessed 2021 January 8).

- 28.Ku, J. Pausing to Reflect and Debrief: Emotional Processing in the Face of Death. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2019. https://cptlpulses.com/2019/05/28/pausing-to-reflect-and-debrief-emotional-processing-in-the-face-of-death/ (accessed 2021 January 8).

- 29.World Health Association. 2021. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en (accessed 2021 May 11).

- 30.Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014. Jun 26;370(26):2506-2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mercadante S, Gregoretti C, Coregiani A. Palliative care in intensive care units: why, where, what, who, when, how. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018; 18: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aslakson RA, Curtis RJ, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014. Nov;42(11):2418-2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker KA, Scarpaci L, McPherson ML. Fifty reasons to love your palliative care pharmacist. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010. Dec;27(8):511-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herndon CM, Nee D, Atayee RS, et al. ASHP guidelines on the pharmacist’s role in palliative and hospice care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016. Sep;73(17):1351-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]