Abstract

Objective. The hidden curriculum has been defined as teaching and learning that occur outside the formal curriculum and includes the knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviors, values, and beliefs that students consciously or subconsciously acquire and accept. It has been identified as an inherent part of learning in health professions education and may affect students’ formation of professional identity. This scoping review investigated the definition and evidence of the hidden curriculum for pharmacy education.

Findings. A comprehensive literature search was conducted for primary articles investigating the hidden curriculum in pharmacy education through August 2021. A total of five papers were included in the review: four papers from the United Kingdom and one from Sweden. The focus of each paper and the elements of the hidden curriculum, along with the study quality as assessed by the quality assessment tool, varied. Three papers focused on professionalism or professional socialization, and the other two focused on patient safety. All five studies used qualitative methods including focus groups and semistructured interviews of the students and faculty. Studies also identified approaches to addressing the hidden curriculum, such as integrating formal and informal learning activities, integrating work experiences, providing sustained exposure to pharmacy practice, and development of professionalism.

Summary. The definition of the hidden curriculum varied across the five studies of varying quality. The evidence of the hidden curriculum was measured qualitatively in experiential and academic settings. Recognition of the impact of the hidden curriculum and strategies for addressing its negative effects are critical to the success of not only the students but also the pharmacy profession at large.

Keywords: hidden curriculum, informal curriculum, pharmacy education, professional identity, health professions

INTRODUCTION

The hidden curriculum has been defined in education as the knowledge, skills, or attitudes that are not specifically covered in textbooks, lectures, laboratories, and course objectives but that students learn, take, inherit, or observe through their educational journey in a program.1-3 This is in comparison to the formal curriculum, which is defined as the “staged, intended, and formally offered, and endorsed curriculum (ie, published curriculum).”4 Metaphorically explained by Gardner in 2010, the hidden curriculum may include an instructor’s own personal agenda, behavior, and attitudes, as well as institutional policies and values, whether they are intentionally or unintentionally conveyed.1 Systematically described by Wallman and colleagues,2 the hidden curriculum is an informal curriculum divided mainly into four categories: learning occurring outside formal education settings, experiential learning occurring in everyday work and reflection of those experience, “incidental learning” or intentional learning from a work context, and relational learning arising from social interactions. An example of the hidden curriculum could be when a faculty member creates a patient case that conveys a medication error and unintentionally includes negative perceptions of a certain type of health care professional (ie, “because doctors are always rushing”). This statement conveys a negative perception without being the intent of the case. Because professional knowledge is acquired through a combination of academic, organizational, and practice-based learning across both formal and informal settings and mechanisms, the hidden curriculum is part of learning but is challenging to measure because it may not be in the objectives, lecture slides, or assessments, but should not be ignored.5

Given the acceptance of learning through the hidden curriculum in health professions education, the hidden curriculum may affect not only the students but also the faculty, program, patients, and the entire health care entity—positively or negatively. Students consciously or subconsciously accept the values, behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions learned through the hidden curriculum; the problem arises when this informal learning becomes impressed and imprinted on learners in ways to override, negate, or undo the intended original curriculum that has a more balanced and intentional view of patients, providers, and the health care system.3 Because a professional learning environment provides an inherently community-based experience with socialization and professional development, the hidden curriculum may also convey messages that elicit inappropriate beliefs and behaviors toward patients, colleagues, and other health care professionals based on characteristics or hierarchy.6 For example, in medical education, the hidden curriculum has been found to elicit negative and cynical views about the profession and physician professional identity.3 Thus, the hidden curriculum becomes concerning when it may taint a student’s perception about the patient-clinician relationship, interprofessional practice, professional norms and ethics, and patient outcomes.

In pharmacy education, aspects of the hidden curriculum have been mentioned frequently in the literature but often without explicit definitions, descriptions, or outcome data.1,7-28 Given that the first strategic priority of the 2021-2024 American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy is to “foster a professional culture of change and transformation in pharmacy,”29 the influences of the hidden curriculum are worth exploring, clearly defining, and reflecting on to achieve this goal. While there are assumptions about potential negative effects of the hidden curriculum in pharmacy education, the extent to which it affects overall curriculum, student learning, and professional identity is unknown. This confusion may be due to a lack of systematic and reliable evidence from which to make appropriate decisions and correct the course. Therefore, the objective of this scoping review is to investigate the definition and evidence of the hidden curriculum used in the primary research for pharmacy education. Additionally, this review discusses the effects of the hidden curriculum on learning and the strategies to assess and prevent its negative consequences on student learning.

METHODS

A systematic literature search of six databases was conducted by a health sciences librarian. Based on the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA),30 multiple databases were used to retrieve relevant articles, including MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Academic Search Complete (Ebsco), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (Ebsco), ERIC (ProQuest), and the Web of Science Conference Proceedings (Clarivate). The search was broken into concept groups; one group encompassed terminology related to the hidden or implicit nature of the hidden curriculum (hidden or informal or implicit or tacit), while a second group contained education-related terminology (curricul* or teach* or taught or training or learn* or education or pedagogy or knowledge). The search was focused only on those papers that dealt with the field of pharmacy (pharm*). Searches were performed on August 23, 2021 with no publication date restrictions, and results were limited to the English language. Citations of each included article were reviewed to find any potential articles missed from the database search. After deduplication in EndNote (Clarivate), references remaining were uploaded into Covidence version 2.0 (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd), a systematic review management software.

Articles were included in the review if they focused on the hidden curriculum, the implicit curriculum, or the informal curriculum; studied a pharmacy program’s curricula as primary research; and were written in English. Articles were excluded if they were commentaries, letters to the editor, books, posters without any data, editorial or non-peer-reviewed publications, or published only as an abstract with minimal data; if they did not focus on the hidden curriculum; or if they did not report any outcomes, results, or solutions related to the hidden curriculum. Using Covidence, a two-step review process was conducted; an initial screening of titles and abstracts was followed by a full-text review. All five investigators independently reviewed the retrieved articles and discussed their merit for inclusion via consensus building; an article was advanced to a full-text review if at least three reviewers approved. The full text was reviewed to ensure that the article met inclusion criteria; at least three investigators needed to agree to include the article in the review.

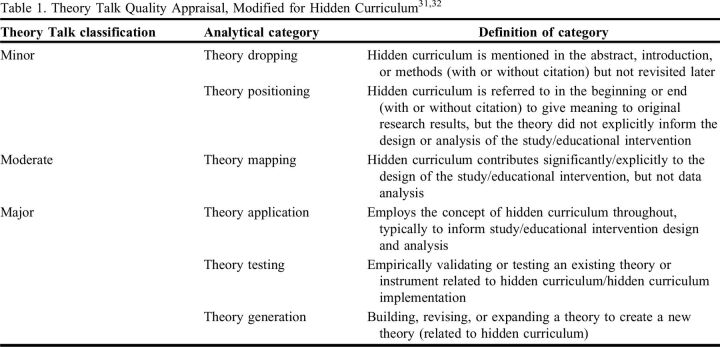

Key elements of each included study were extracted to describe the objective, study population, setting, design, methods, definitions, and findings. All investigators reviewed the data extraction tables for accuracy. To conduct a quality assessment of included articles, a modified version of the Theory Talk method was used.31,32 This method has been used in other scoping reviews within pharmacy and other health professions, relates well to educational research that has a variety of methodologies and approaches examining a concept, and addresses a theory or concept (Table 1).31,32 The quality assessment is a standard approach in reviews to examine the usefulness of each included article, and the Theory Talk served as a tool to examine how connected a paper was to a theory or concept (ie, how deeply each article discussed and addressed the hidden curriculum). Each article included in the review was evaluated independently by at least two reviewers and, subsequently, by a third reviewer for vetting and resolving discrepancies or conflicts. As a final step, the authors conducted data synthesis, namely a thematic approach to make sense of the data. During this step, the authors identified the conceptualization of the hidden curriculum, the aspects of the hidden curriculum that were explored, and the implications for pharmacy education using a consensus approach.

Table 1.

RESULTS

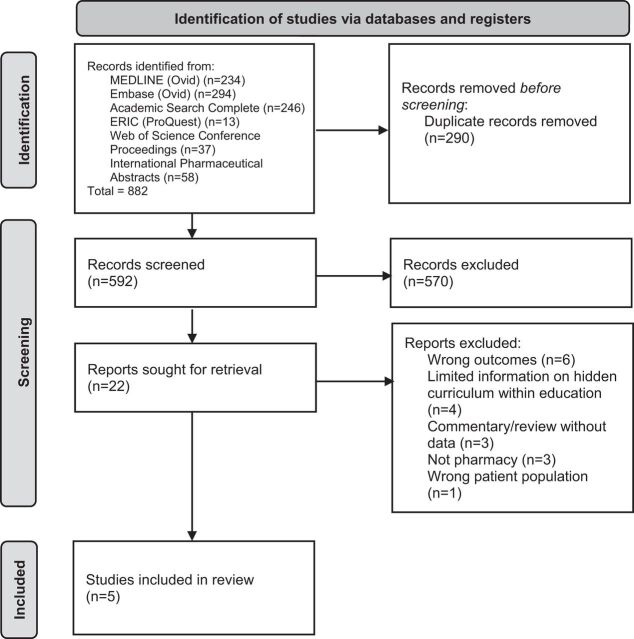

The PRISMA diagram generated by the search and review process can be found in Figure 1. A search of the six databases returned a combined total of 882 results. Titles of the citations for each included article were reviewed to find any potential articles missed from the database search. After deduplication in EndNote, 627 references remained and were uploaded into Covidence. After the review process, five articles met inclusion criteria. Most articles were excluded because they did not focus on the hidden curriculum or did not report any outcomes, results, or solutions related to the hidden curriculum. A summary of the articles can be found in Appendix 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram illustrating the hidden curriculum search and review process.30

The primary literature related to the hidden curriculum included in this scoping review were found to have used either Hafferty’s (1998)33-36 or Eraut’s (2004)2,5 definition of hidden curriculum in their studies. Hafferty4 defined the hidden curriculum as “A set of influences that function at the level of organization structure and culture and include customs, rituals, commonly held ‘understandings,’ and the ‘taken for granted’ aspects of a profession.” Eraut’s definition37 uses the term informal learning to describe the hidden curriculum; informal learning occurs “outside formal education settings, is intentional or incidental, often experiential, and relational.” The studies came mainly from the United Kingdom and occurred within the experiential setting; there were no available studies from the United States that met inclusion criteria. All five studies used qualitative methods of collecting and analyzing data, including focus groups and semistructured interviews of students and faculty. Three papers focused on professionalism or professional socialization,2,35,36 and the other two focused on patient safety.5,33

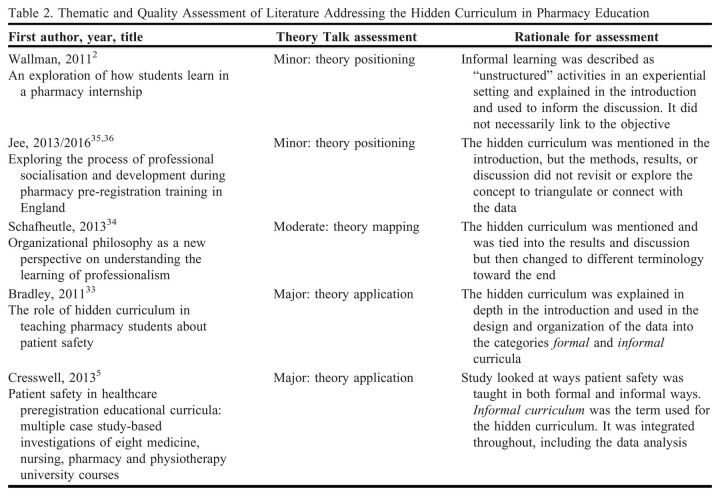

Two hidden curriculum practices emerged from the reviewed studies: questioning/reflection2,5 and role modeling.33,35,36 Applying the Theory Talk assessment,31,32 the articles had a varying level of quality; specifically, two articles had minor alignment to the hidden curriculum,2,35,36 one had moderate alignment,34 and two had major alignment.5,33 Details on the Theory Talk assessment and rationale can be found in Table 2. For questioning and reflection, students felt that the most important learning came from asking questions, observing, listening, being supervised, and then reflecting on the experience.2 Students identified this as even more important than the formal classroom learning and the structured activities during the experiences. Additionally, students felt that they learned about patient safety more through spontaneous conversations with practitioners as opposed to the formal curriculum.5

Table 2.

Thematic and Quality Assessment of Literature Addressing the Hidden Curriculum in Pharmacy Education

The other practice in the hidden curriculum was role modeling as two studies found that students looked to the practitioners (both pharmacists and nonpharmacists) teaching or precepting them as role models. Nonpharmacists in these studies were defined as pharmacy technicians, dispensers, counter assistants (in community settings), and assistant technical officers (in hospital settings). The role modeling provided students with the socialization skills needed to function in the work setting as these skills were not taught typically in the formal curriculum.35,36 Students felt that watching practitioners provide them with the ability to compare and contrast methods of how to handle situations, such as patient safety, and then being allowed to make their own mistakes further solidified the information that they learned in the formal curriculum.33

The hidden curriculum was shown to have both positive and negative consequences on student learning according to the literature. For the positive consequences, students reported that watching practitioner role models positively influenced their professional development particularly in areas that were harder to demonstrate in the lecture setting, such as patient safety.33 Students also felt that reflecting on their own errors with the help of a professional greatly helped to cement the importance of the patient safety concepts that they learned in the formal curriculum.

Negative consequences of the hidden curriculum were noted in several studies. For example, students can sometimes feel exploited in experiential settings as they become more incorporated into a work environment. It was noted that they may not have understood what they should be learning in all situations as they may have considered many activities busywork as opposed to true learning. This can make the informal/hidden learning time counterproductive.2 Another negative consequence was an inability to reconcile differences in formal curriculum content and what was seen in the experiential setting, which many times contains more of the hidden curriculum; this can lead to unnecessary confusion for the student.5 Students may also find that the hidden curriculum changes depending on the location of the training, the specific role model, and the extent of their involvement in patient care activities. This can make it difficult for students to apply their clinical knowledge and communication skills as they may be receiving mixed messages on correct behavior.35,36

The literature found in this scoping review discusses several strategies to help prevent the negative consequences that can occur with hidden curriculum.2,5,33-36 One strategy is to ensure that the organization has an “integrated” philosophy in which there is an overlap between intended, taught, and received curricula and, thus, allows for clear, reinforced, and enforced expectations. To achieve an integrated philosophy, an organization needs to be aware of both the formal and hidden curricula.33,34 Another method is to raise awareness of the hidden curriculum within programs and then find ways to use it in a positive manner.2 Lastly, encouraging a strong and positive mentor relationship between students and practitioners can help.5 The last two methods can be improved through the use of professional development to help reduce variation in students’ experiences and professional socialization and development.35,36

DISCUSSION

While pharmacy education may not have explored the definition and practice of the hidden curriculum in depth, this term has been in the lexicon of higher education for some time.1,7-28 In our review, we did not find substantial differences between pharmacy education literature and other health professions literature; instead, more nuanced elements were found given the nature of the pharmacy curriculum. The hidden curriculum has also penetrated medicine and nursing education, with both professions having sufficient literature to describe and define it.3,5 Medical education has long been dealing with differentiating its formal or explicit curriculum (published curriculum) from the informal or hidden curriculum. Here, the hidden curriculum has been loosely described as cultural norms, ethics,38 and incongruence between what students learn and what they are taught;4 Hafler and colleagues39 defined it as a learning dimension that includes social interaction, cultural traditions, informal norms, stereotypes, and social practices. Through a review of the literature in medical education, Lawrence and colleagues40 found that the hidden curriculum has four distinct conceptual characteristics: institutional-organizational, interpersonal-social, contextual-cultural, and motivational-psychological.

Among the articles included in this review for pharmacy education, the two definitions cited were from Hafferty4 and Eraut.37 Combining these two definitions may be useful in generating a definition of the hidden curriculum in pharmacy education; thus, it may be defined as learning that occurs outside the formal educational setting that is influenced by the customs, rituals, and commonly held understandings of the organization or professional culture and most often occurs in experiential or relational settings. This definition fits with the definitions commonly seen in the medical and nursing literature,3,5 includes the concept that it is learning that occurs outside the formal educational setting, and, as is discussed later, may elicit the potential incongruence between what is learned and what is taught.38 This definition also discusses the institutional-organizational characteristic, the interpersonal-social aspect, and the cultural aspect, but does not include the motivational-psychological part.40 Having a common definition of the hidden curriculum in pharmacy education would make performing future research on this subject consistent.

In pharmacy education, the hidden curriculum may begin when the student begins experiential learning in introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs) and become more apparent during an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE), as the student realizes that there are many constraints and “gray areas” to practicing pharmacy as opposed to the way that they were taught in class. As noted by Cresswell and colleagues,5 this was often related to patient safety where many factors influence clinical and administrative decision-making.6 Using the two hidden curriculum practices that emerged from these articles, namely questioning/reflection2,5 and role modeling,33,35,36 students may be directed to work through the experience and reconcile the incongruence between classroom and experiential learning. For the use of questioning and reflection, students felt that they learned more during these sessions with practitioners than they did in the formal curriculum, and that the opportunities for questioning and reflection were sometimes more important than the structured activities provided during experiences.2,5

The importance of mentorship or role modeling was seen throughout the articles included in this review. Role modeling provides students with socialization skills and the ability to compare and contrast different methods of handling situations.33,35,36 Other scoping reviews have found this to be a key element.40,41 Instructors are viewed as role models and students as impressionable learners who observe the instructor’s behaviors and attributes while engaging in clinical instructions or patient interactions. During these encounters, the student will inevitably absorb the instructor’s mannerisms, tone, beliefs, and thought processes, whether intended or not.3 Thus, the hidden curriculum, particularly mentoring, can be impactful on students and their well-being and should be a priority for consideration by programs; it would be critical for programs to provide faculty and preceptor development in the areas of role modeling and mentorship to facilitate students’ development of professional identity.

The methods of raising awareness of the hidden curriculum and encouraging strong mentoring relationships can be improved through the use of professional development to help reduce variation in experiences and professional socialization and development.35,36 Faculty and preceptor development efforts may also be beneficial to mitigate the implications of the hidden curriculum by addressing intentionality and structure in learning, explaining the importance of changing and revising curricula to meet current practice, and providing bridging between the classroom and experiential learning. This approach needs to be collaborative across departments and disciplines to enhance student learning. Chuang and colleagues3 recommend a five-step process for faculty to consider, including reflecting on interactions, identifying stakeholders in student education, collecting data on the interactions between stakeholders and students, analyzing the data, and disseminating the data, with an emphasis on continuous quality improvement. This is similar to some of the recommendations related by Olson and colleagues42 but broadens the scope of the reflection and collection process.

Further information is needed on the hidden curriculum within the didactic curriculum, as the studies included were focused on experiential learning. Olson and colleagues42 published a systematic review regarding the hidden curriculum that may undermine the conceptualization of patient centeredness among students. They noted that this topic could be formally or informally addressed and defined the hidden curriculum as “tacit, inconspicuous, and commonly unintended lessons about what is ‘actually expected’ from students that differ from a school’s formal standards.” The authors provided definitions of patient centeredness and gave recommendations for programs to assess and address the hidden curriculum elements.42 The questions for identifying and evaluating the hidden curriculum related to patient-centered care could be a useful tool for other programs to examine how the hidden curriculum could “lurk” in their own teaching and learning. Further work should examine other concepts that are hidden in pharmacy curricula beyond patient-centered care.

The hidden curriculum can have a variety of effects on students. When the hidden curriculum aligns or overlaps with the professional curriculum, it can have a positive impact (eg, improving the professionalism of students).34 However, when it does not align as intended, it can create challenges that are difficult to discern. Similarly, differences between curricular and practice-based expectations can create cognitive dissonance for students and cause them to be unsure of what is acceptable and what is not. In the study by Cresswell and colleagues,5 students could not reconcile different approaches to patient safety in different learning settings. However, studies recognize clear benefits from informal learning2,33 because some principles are difficult to convey or learn in the classroom. Learning may not even be possible until students can learn from their own mistakes, creating value for important concepts such as patient safety.33 Moreover, it is critical to link theory and practice,33 which may be an important concept for programs to consider, and curricular and experiential learning should work together throughout pharmacy education with the benefits of the informal curriculum in mind. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Standards 2016 encourages programs to use cocurricular and experiential learning in a way that reinforces and enhances classroom learning.43

Bandini and colleagues44 found that student self-reflection that occurred through either small group discussions or mentorships positively impacted thinking about the hidden curriculum and resolved discrepancies between classroom and clinical learning. Therefore, allowing opportunities for students to reflect or encouraging faculty advisors and mentors to ask students self-reflective questions about the hidden curriculum could be beneficial. This approach can also provide a meaningful foundation for assessing the hidden curriculum, namely through comparing student perspectives on what is taught to what is in the curricular map.42 This may allow faculty to better understand content or concepts that were emphasized more than intended or should be removed.42 Student focus groups could be another approach to obtaining feedback on content that is implicitly and explicitly expressed in a variety of settings—curricular, cocurricular, and experiential. Time for students to self-reflect and evaluate their learning with peers or mentors could be beneficial to prevent the negative consequences of the hidden curriculum on student learning.2,5,35,36

This paper provides a potential starting definition for the hidden curriculum in pharmacy education in the United States; this definition will need to be refined with future research to be in line with curricular requirements in the United States. It also explores the practice of the hidden curriculum in global pharmacy education and brings to light the limited data available on this topic, especially in the United States. From the starting point of a definition and understanding available data, the Academy can formulate future research plans to address this topic, given the implications for student well-being and learning. It could be noteworthy to examine how the integration of experiential and other learning alongside the curriculum may address these issues as the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Standards 2016 encourages programs to use cocurricular and experiential learning in a way that reinforces and enhances classroom learning.43 International curricula can have more segmented didactic and experiential learning due to different educational standards. Thus, hidden curricula could occur elsewhere.

Given the results of this review, are any elements of the curriculum truly hidden? Margolis and colleagues45 argued that the hidden curriculum is not entirely hidden when the instructor is aware of the problem. It remains behind the scenes of the overall curriculum and reveals itself in the forms of subordination and discrimination that benefit some at the cost of others involved, such as race and gender hierarchies embedded in the psyche, discourse, and attitude.45 As found in this scoping review, there are several ways to help prevent the negative consequences that can occur with the hidden curriculum.2,5,35,36 One strategy is to ensure that a pharmacy program has an “integrated” philosophy as defined above, which allows for a program to have clear, reinforced, and enforced expectations.33,34 Another method is to raise the awareness of the hidden curriculum within programs and then find ways to use it in a positive manner.2

There are several limitations to this review. Some articles that include or discuss an aspect of the hidden curriculum may have been missed, given that the definition of the hidden curriculum is still nuanced and unfamiliar to the pharmacy Academy. However, a rigorous process was used with hand-searches of reference lists to maximize the evidence generated. Another limitation was the small number of articles on the hidden curriculum in pharmacy education, making generalizations of the results difficult to apply to all pharmacy programs. However, the authors were able to glean insights from articles from other health professions due to some similarities in learning occurring in the classroom and experientially. Lastly, all the articles found were from outside the United States. Thus, there could be cultural, curricular, and experiential differences that may enhance or mitigate some of the findings. These limitations could be explored in future research. Gaining further understanding of the impact of the hidden curriculum on student learning and developing strategies for addressing the potential negative effects within the United States are critical to the pharmacy profession at large.

CONCLUSION

The hidden curriculum can be defined as the learning that occurs outside the formal educational setting, influenced by the customs, rituals, and commonly held understandings of the organization or professional culture. It commonly occurs in health professions education and most often in experiential learning. It may affect students’ learning by creating cognitive dissonance between what is taught in the classroom and the practicality of working in health care. Without clear reflection opportunities and mentorship, students may struggle to reconcile these differences. The hidden curriculum can also have positive effects, such as helping students improve their professionalism and allowing them to learn from their mistakes. Research regarding the impact of the hidden curriculum on student learning and strategies for addressing the potential negative effects within the United States are critical to the success of not only students but also the pharmacy profession.

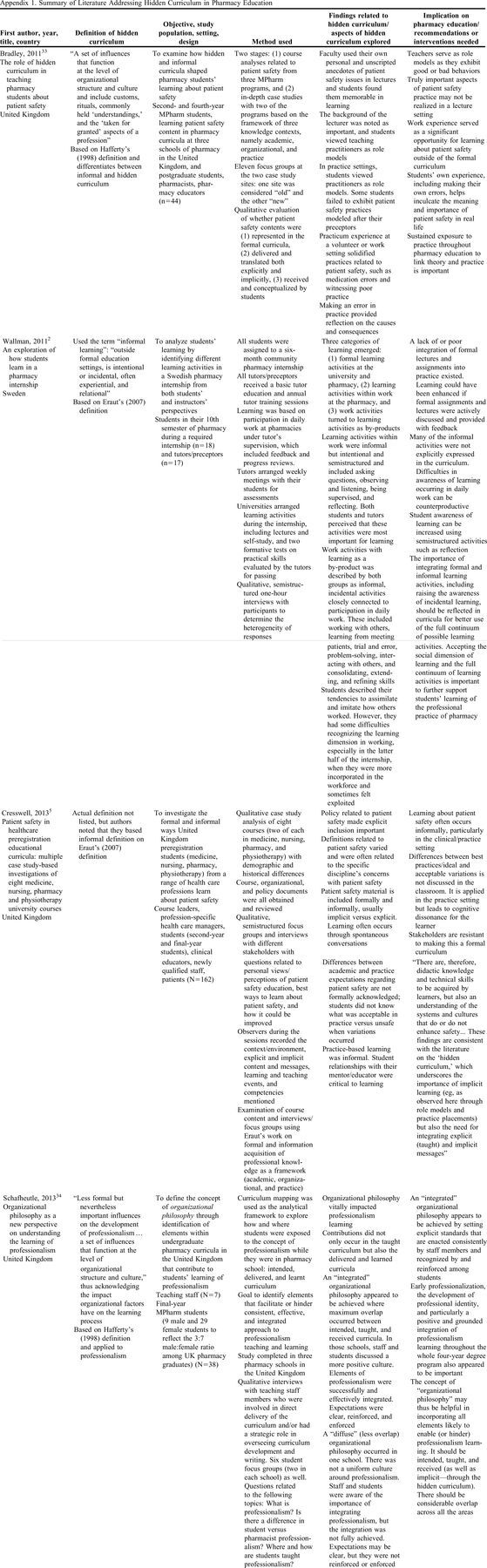

Appendix 1.

Summary of Literature Addressing Hidden Curriculum in Pharmacy Education

REFERENCES

- 1.Gardner S. Car keys, house keys, Easter eggs, and curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(7):Article 133. doi: 10.5688/aj7407133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallman A, Gustavsson M, Lindblad AK, Ring L. An exploration of how students learn in a pharmacy internship. Pharmacy Education. 2011;11(1):177-182. Accessed March 11, 2023. https://pharmacyeducation.fip.org/pharmacyeducation/article/view/306 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuang AW, Nuthalapaty FS, Casey PM, et al. To the point: reviews in medical education-taking control of the hidden curriculum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):316.e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine's hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403-407. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cresswell K, Howe A, Steven A, et al. Patient safety in healthcare preregistration educational curricula: multiple case study-based investigations of eight medicine, nursing, pharmacy and physiotherapy university courses. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(10):843-854. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahood SC. Medical education: Beware the hidden curriculum. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(9):983-985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allinson MD, Black PE, White SJ. Professional dilemmas experienced by pharmacy graduates in the United Kingdom when transitioning to practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(9):Article 8643. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padilla D, Bell HS. Flexner, educational reform, social accountability and meta-curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(1):Article 6817. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akiyode O. Teaching professionalism: a faculty’s perspective. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2016;8(4):584-586. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2016.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black EP, Policastri A, Garces H, Gokun Y, Romanelli F. A pilot common reading experience to integrate basic and clinical sciences in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(2):Article 25. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle CJ, Robinson ET. Leadership is not a soft skill. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 209. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nonyel NP, Wisseh C, Riley AC, Campbell HE, Butler LM, Shaw T. Conceptualizing social ecological model in pharmacy to address racism as a social determinant of health. Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(9):8584. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman J, Chung E, Hess K, Law AV, Samson B, Scott JD. Overview of a co-curricular professional development program in a college of pharmacy. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9(3):398-404. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopkins L, Saciragic L, Kim J, Posner G. The hidden curriculum: exposing the unintended lessons of medical education. Cureus. 2016;8(10):e845. doi: 10.7759/cureus.845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janke KK, Thornby KA, Brittain K, et al. Embarking as captain of the ship for the curriculum committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(9):Article 8692. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellar J, Paradis E, van der Vleuten CPM, Oude Egbrink MGA, Austin Z. A historical discourse analysis of pharmacist identity in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(9):Article 7864. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiles TM, Chisholm-Burns M. Five essential steps for faculty to mitigate racial bias and microaggressions in the classroom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(9):Article 8796. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDonnell CP, Rege SV, Misto K, Dollase R, George P. An introductory interprofessional exercise for healthcare students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(8):Article 154. doi: 10.5688/ajpe768154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JK, Tomasa L, Evans P, Pho VB, Bear M, Vo A. Impact of geriatrics elective courses at three colleges of pharmacy: attitudes toward aging and eldercare. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2019;11(12):1239-1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2019.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mylrea MF, Gupta TS, Glass BD. Professionalization in pharmacy education as a matter of identity. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015; 79(9):142. doi: 10.5688/ajpe799142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nahata MC. Our assets, achievements and aspirations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66(Winter):432-435. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sikora A, Murray B. Addressing matters of life and death in the pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(9):Article 8636. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prescott J, Becket G, Wilson SE. Moral development of first-year pharmacy students in the United Kingdom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(2):Article 36. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogt EM, Robinson DC, Chambers-Fox SL. Educating for safety in the pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(7):Article 140. doi: 10.5688/ajpe757140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeeman JM, Bush AA, Cox WC, Buhlinger K, McLaughlin JE. Identifying and mapping skill development opportunities through pharmacy student organization involvement. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(4):6950. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zorek JA, Katz NL, Popovich NG. Guest speakers in a professional development seminar series. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(2):Article 28. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith MG, Dinkins MM. Early introduction to professional and ethical dilemmas in a pharmaceutical care laboratory course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(10):Article 156. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7910156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burkhardt C, Crowl A, Ramirez M, Long B, Shrader S. A reflective assignment assessing pharmacy students interprofessional collaborative practice exposure during Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(6):Article 6830. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. 2021–2024 strategic plan priorities, goals and objectives. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/aacp-strategic-plan–2021-2024.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2023.

- 30.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumasi KD, Charbonneau DH, Walster D. Theory talk in the library science scholarly literature: an exploratory analysis. Libr Inf Sci Res. 2013;35:175-180. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2013.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson NR, Carlson RB, Corbett AH, Williams DM, Rhoney DH. Feedback for learning in pharmacy education: a scoping review. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(2):91. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy9020091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley F, Steven A, Ashcroft DM. The role of hidden curriculum in teaching pharmacy students about patient safety. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(7):Article 143. doi: 10.5688/ajpe757143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schafheutle EI, Hassell K, Ashcroft DM, Harrison S. Organizational philosophy as a new perspective on understanding the learning of professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):214. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jee SD, Schafheutle EI, Noyce PR. The professional socialisation of trainees during the early stages of preregistration training in pharmacy. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(Suppl. 1):1. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jee SD, Schafheutle EI, Noyce PR. Exploring the process of professional socialisation and development during pharmacy pre-registration training in England. Int J Pharm Pract. 2016;24(4): 283-293. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eraut M. Informal learning in the workplace. Stud Contin Educ. 2004;26(2):247-273. doi: 10.1080/158037042000225245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69(11): 861-871. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hafler JP, Ownby AR, Thompson BM, et al. Decoding the learning environment of medical education: a hidden curriculum perspective for faculty development. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):440-444. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820df8e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawrence C, Mhlaba T, Stewart KA, Moletsane R, Gaede B, Moshabela M. The hidden curricula of medical education: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):648-656. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000002004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pourbairamian G, Bigdeli S, Soltani Arabshahi SK, et al. Hidden curriculum in medical residency programs: a scoping review. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2022;10(2):69-82. doi: 10.30476/jamp.2021.92478.1486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olson AW, Isetts BJ, Stratton TP, Vaidyanathan R, Hager KD, Schommer JC. Addressing hidden curricula that subvert the patient-centeredness “hub” of the Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process “wheel.” Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(9):Article 8665. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2023.

- 44.Bandini J, Mitchell C, Epstein-Peterson ZD, et al. Student and faculty reflections of the hidden curriculum: How does the hidden curriculum shape students’ medical training and professionalization? Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34(1):57-63. doi: 10.1177/1049909115616359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Margolis E, Soldatenko M, Acker S, Gair M. Peekaboo. Hiding and outing the curriculum. In: Margolis E, Soldatenko M, Acker S, Gair M, eds. The Hidden Curriculum in Higher Education. New York, NY: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]