Abstract

Despite data suggesting that older adolescence is an important period of risk for HIV acquisition in Uganda, tailored HIV prevention programming is lacking. To address this gap, we developed and tested nationally, InThistoGether (ITG), a text messaging-based HIV prevention program for 18–22 year-old Ugandan youth. To assess feasibility and acceptability, and preliminary indications of behavior change, a randomized controlled trial was conducted with 202 youth. Participants were assigned either to ITG or an attention-matched control group that promoted general health (e.g., self-esteem). They were recruited between December 2017 and April 2018 on Facebook and Instagram, and enrolled over the telephone. Between 5–10 text messages were sent daily for seven weeks. Twelve weeks later, the intervention ended with a one-week ‘booster’ that reviewed the main program topics. Measures were assessed at baseline and intervention end, 5 months post-randomization. Results suggest that ITG is feasible: The retention rate was 83%. Ratings for the content and program features met acceptability thresholds; program experience ratings were mixed. ITG also was associated with significantly higher rates of condom-protected sex (aIRR = 1.68, p < 0.001) and odds of HIV testing (aOR = 2.41, p = 0.03) compared to the control group. The odds of abstinence were similar by experimental arm however (aOR = 1.08, p = 0.86). Together, these data suggest reason for optimism that older adolescent Ugandans are willing to engage in an intensive, text messaging-based HIV prevention programming. Given its wide reach and low cost, text messaging should be better utilized as an intervention delivery tool in low-income settings like Uganda. Findings also suggest that ITG may be associated with behavior change in the short-term. (Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov ID# NCT02729337).

Keywords: MHealth, Uganda, HIV prevention, Adolescents

Resumen

A pesar de que los datos sugieren que la adolescencia mayor es un período importante de riesgo de contraer el VIH en Uganda, hace falta una programación de prevención del VIH personalizados. Para abordar esta brecha, desarrollamos y probamos a nivel nacional, InThistoGether (ITG), un programa de prevención del VIH basado en mensajes de texto para jóvenes ugandeses de 18 a 22 años. Para evaluar la viabilidad y aceptabilidad, y las indicaciones preliminares del cambio de comportamiento, se realizó un ensayo controlado aleatorio con 202 jóvenes. Los participantes fueron asignados a ITG o a un grupo de control de atención que promovía la salud general (p.ej., la autoestima). Fueron reclutados entre diciembre de 2017 y abril de 2018 en Facebook e Instagram y se inscribieron por teléfono. Se enviaron entre 5 y 10 mensajes de texto diariamente durante siete semanas. Doce semanas después, la intervención terminó con un “refuerzo” de una semana que repasó los principales temas del programa. Las medidas se evaluaron al inicio y al final de la intervención, 5 meses después de la aleatorización. Los resultados sugieren que ITG es factible: la tasa de retención fue 83%. Las calificaciones del contenido y las características del programa alcanzaron los umbrales de aceptabilidad; las calificaciones de experiencia del programa fueron mixtas. La ITG también se asoció con tasas significativamente más altas de relaciones sexuales protegidas con condón (aIRR = 1.68, p < 0.001) y probabilidades de pruebas de VIH (aOR = 2.41, p = 0.03) en comparación con el grupo de control. Sin embargo, las probabilidades de abstinencia fueron similares en el grupo experimental (ORa = 1,08, p = 0,86). Juntos, estos datos sugieren razones para el optimismo de que los adolescentes ugandeses mayores están dispuestos a participar en un programa intensivo de prevención del VIH basado en mensajes de texto. Dado su amplio alcance y bajo costo, los mensajes de texto deberían utilizarse como una herramienta de entrega de intervenciones en lugares de bajos ingresos como Uganda. Los hallazgos también sugieren que ITG puede estar asociada con cambios de comportamiento a corto plazo.

Introduction

In 2019, Uganda was estimated to have the 11th highest adult HIV prevalence rate in the world: [1] 5.7%, 1.4 million people, are living with HIV [2]. Heterosexual sex is the primary mode of transmission of HIV in Uganda [3], which is likely why prevalence rates increase dramatically from middle to late adolescence as young people start having sex. Indeed, the rate of HIV among young women jumps from 1.6% among 15- to 17-year-olds to 7.1% among 20- to 22-year-olds [4]. Rates also rise for males during this developmental period. It seems evident, then, that curbing the HIV epidemic in Uganda requires HIV programming developed for adolescents as they age through this period of risk.

Cell phone technology is expanding in Sub-Saharan Africa faster than anywhere else in the world [5], representing an opportunity to go where young people “are” with behavior change programming. This is especially true in areas where healthcare infrastructure is limited [6] and contact with hard-to-reach populations at risk for HIV can be difficult (e.g., youth living outside of urban areas) [7]. Intervention delivery via text messaging can overcome many structural challenges and access issues that can plague traditional programs, such as a lack of local healthcare services, a need for transportation to get to the site, etc. Importantly too, in Uganda, text messages are received with no cost to the user [8]. As such, text messaging may be an effective delivery mechanism to affect a wider public health reach for intervention programming.

Text messaging is being used to improve HIV-related healthcare and programming in Uganda and other sub-Saharan African countries [9]. While programs to improve medication adherence appear promising [10–13], other types of behavior change have been less successful [9]. For example, Google and Grameen Technology Center developed an ask-and-answer program implemented across 60 different villages in Uganda [14]. Interest appeared strong (40% sent at least one question to the service during the program), yet norms were unaffected and rates of HIV risk behavior may have increased among users of the service. In a separate study conducted in the town of Arua by Text to Change, thirteen multiple-choice questions relating to HIV/AIDS and HIV testing were sent via text messages to 10,000 phone numbers [15]. Although one in five participants responded to at least one question, only 0.3% answered every question, and only 2.3% of total participants used the program incentive to receive free HIV testing during the program period. Together, these studies suggest that HIV-related text messages may be acceptable. Beyond acceptability however, there is a dearth of data supporting the feasibility of text messaging-based HIV prevention programs, particularly those that are comprehensive and theory-driven. This is a necessary gap to fill given that these types of programs are more likely than brief programs to be associated with behavior change.

Condom use at first sex is a crucial factor influencing current condom use [16–20], yet few HIV prevention programs include sexually inexperienced youth. To maximize opportunities to improve lifelong HIV preventive behavior, HIV interventions need to include young people prior to their sexual debut. Also, intervention content must go beyond issues surrounding the use of condoms. An estimated 45% of men and 19% of women living with HIV in Uganda do not know their HIV sero-status [21], making HIV testing a necessary and central component of any HIV prevention study in Uganda.

Current Paper

InThistoGether (ITG) is a text messaging-based HIV prevention program designed to address the unique experiences of older adolescents across Uganda. This intervention is novel in many ways: To our knowledge, it is the first HIV prevention program in eastern Africa to be: (1) a comprehensive, theory-driven text messaging-based HIV prevention program; (2) that was developed as well as tested at the national level, and (3) tailored specifically for older adolescents. Formative development activities are reported elsewhere [22]. Here, we report outcomes from the pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT). Findings have the potential to build knowledge about feasible and acceptable strategies to reach and engage this important population in HIV prevention programming.

Methods

This two-arm pilot RCT was conducted in Uganda. Chesapeake IRB (now Advarra IRB) and the Mbarara University Science and Technology Research Ethics Board reviewed and approved the protocol.

Participants

Participants were recruited nationally. Eligibility criteria included: (a) living in Uganda; (b) being 18 to 22 years old; (c) being able to read English; (d) being the sole user of a cell phone; (e) using text messaging for at least 6 months; (f) intending to have the same phone number for the next six months; (g) being able to access the Internet to complete online surveys; and (h) being able to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included knowing another person enrolled in the RCT, and participating in an intervention development study activity (e.g., focus groups).

Study Settings

Participants were recruited through online advertisements on Facebook, one of the most visited websites in Uganda [23, 24], between December 2017 and April 2018. Because of the integration of the two platforms, advertisements also were shown on Instagram. Advertisements targeted profiles of people who were between 18 to 22 years old and lived in Uganda. Those who were interested clicked on the advertisement, which linked them to the online screener form. Completed screeners were stored on the password-protected project website. Project staff then contacted eligible candidates and scheduled a phone appointment to confirm eligibility, complete a self-safety assessment [25], and obtain informed consent. Although participants were 18 years of age and older, a self-safety assessment was deemed necessary given the cultural sensitivity of the topics discussed in the program. Youth who consented were then emailed a survey link to the baseline survey. They were encouraged to complete the survey online and on their own. After survey completion, they were randomized and began receiving text messages.

A diverse sample was enrolled by identifying a priori recruitment targets across key demographic characteristics. People were contacted sequentially based upon when their screener was submitted; youth representing demographic characteristics under-represented in the sample were prioritized.

Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to the intervention (n = 101) or control (n = 101) arms by a computer program designed to minimize the likelihood of imbalance between the study arms with respect to sexual experience (penile-vaginal or penile-anal sex within the past two years versus not) and sex assigned at birth [26].

Blinding

Participants, but not researchers, were blind to arm allocation.

Incentive

Participants received 10,000 UGX in mobile data for the baseline and intervention end surveys, respectively.

Description of the Intervention and Control Group Content

Intervention content was developed iteratively [22]. First, we conducted focus groups with 202 young adults to better understand the sexual decision-making of the target population and to gain ‘voice’ of older adolescents. Messages were then drafted based upon the Information-Motivation-Behavior Model of HIV preventive behavior [27, 28] and tailored based upon findings from the focus groups. Next, content was reviewed by Content Advisory Teams (CATs) comprising 143 older adolescents. Once youth feedback was integrated into the messages and the content was finalized, we conducted an alpha test among the research team and then a ‘real world’ beta test of the intervention and protocol with 34 adolescents.

Final intervention topics included: HIV information (e.g., what it is, how to prevent it), motivation (e.g., reasons why young people use condoms), and behavioral skills (e.g., how to negotiate condom use with one’s partner). Additional topics identified in the focus groups and discussed in the content included: The importance of HIV testing, healthy and unhealthy relationships, societal expectations for gendered sexual interactions between male and female sexual partners, and effective communication strategies within the Ugandan cultural context. The ‘core’ intervention content was delivered over seven weeks and averaged between 5–15 messages a day. Twelve weeks later, a ‘booster’ week reinforced the most important preventive topics discussed in the core program.

The intervention had two game-like features. At the end of each program week, youth had the opportunity to “level up” by answering a question about the previous week’s content. Intervention participants also could earn “badges”, meant to help participants achieve HIV preventive behavioral goals in a concrete, stepwise fashion. Both sexually experienced and inexperienced intervention youth were encouraged to first buy condoms (Badge 1) and then carry condoms with them everywhere they went (Badge 2). Youth who were sexually experienced at baseline subsequently were encouraged to use condoms if they were having sex (Badge 3). All youth also were encouraged to get tested for HIV (Badge 4).

Additionally, based upon previous mHeatlh interventions [29–32], we offered an on-demand feature called ITGenie. It provided scripted “answers” to common questions intervention youth could query, including those that were identified in the focus groups (e.g., how to make a good impression with your partner’s parents). We also paired intervention participants 1:1 as “ITG Peers.” As with other text messaging-based interventions [29–32], the intent was to have them talk with each other about what they were learning in the program and provide support for each other as they endeavored to implement HIV preventive behaviors. Due to persistent technical difficulties, we were unable to implement this last feature.

Although the same concepts were discussed for sexually experienced and inexperienced youth, content was tailored by experience (e.g., “when you are older and start having sex” versus “the next time you have sex…”). Given the high level of stigma in Uganda associated with being HIV positive coupled with the fact that HIV status was not an eligibility criterion, messages were written to be relevant to people who were HIV positive, as well as to reduce stigma for all participants irrespective of their HIV status. As part of our human subjects protocol, the study team reached out to people who reported a positive HIV test to facilitate linkage to care.

Control group participants received a text messaging program matched on the number of days that intervention group participants received. Messages focused on general health topics (e.g., self-esteem). Because program interactivity was posited to increase one’s engagement and enhance the learning effect, level-up questions, badges, and ITGenie were not available to the control group.

Data Collection

Participants in both arms completed a comprehensive assessment at baseline and intervention end, approximately five months after randomization. A brief survey also was conducted at the end of the ‘core’ program. The follow-up period depended on when, after receiving the survey invitation, participants completed the assessment; and how quickly intervention participants responded to bi-directional messages during the program (e.g., if they did not respond to a question, their program messages were paused so they could receive a reminder the following day). Participants who did not complete the survey received both automated and personalized reminders. They also were given the option to complete the survey over the telephone with research staff, if preferred.

Outcomes

Given that this was a pilot RCT, our primary outcome measures were feasibility and acceptability. Behavioral outcome measures were included to provide effect size estimates for a subsequent, fully powered RCT. These outcomes were: (a) using condoms during sex in the past 90 days; (b) abstaining from sex in the past 90 days; and (c) getting tested for HIV in the past 90 days at intervention end, five months post-randomization.

Feasibility

A recruitment rate of at least 35 participants a month was deemed to support a hypothesis of feasibility, as was an 80% retention rate at intervention end.

Thirteen items, based upon previous intervention acceptability scales [33, 34], queried general program acceptability (e.g., likelihood of recommending the program to peers; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.69). Items were asked of both intervention and control participants to help inform if blinding of the control group was successful, in addition to measuring the acceptability of the intervention itself. An additional eight items were asked only of intervention participants and focused on the ITG program experience (e.g., how much they liked the Level Up feature; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88). Items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale; average scores of four or more were deemed supportive of a hypothesis of acceptability.

At the end of the 7 week ‘core’ intervention, participants were asked to estimate the percentage of ITG messages they read in the previous week. An average of 80% of messages read was deemed supportive of program engagement.

At intervention end, participants were asked: “How many times have you played vaginal sex in the past 3 months (90 days)? We mean when a penis goes into a vagina.” [“Played” is the culturally normative way to say one “had” sex.] Those who reported one or more times were asked: “How many times did you use condoms in the past 3 months (90 days) when you played vaginal sex?” Participants also were asked: “How many people have you played anal sex with in the past 3 months (90 days)? We mean when a penis goes into an anus.” Those who said one or more times were asked the number of times they used condoms. Condom-protected sex was a sum of one’s answers for vaginal and anal sex. Those who said they had not played vaginal or anal sex were coded as abstinent.

HIV testing was queried: “In the past 3 months (90 days), have you been tested for HIV?” Those who said “yes” were coded as having been tested.

Power Analysis

Based upon an anticipated 100 sexually active youth in the sample, resulting in 50 sexually experienced participants each in the intervention and control arms, we would have sufficient power to detect a medium-sized effect [35]. For example, if 15% of the control group reported condom use at follow-up, a 25% difference in condom use rates between the intervention and control groups would be statistically significant. If 5% of the control group reported condom use at follow-up, a 20% difference between the two groups would be statistically significant.

Statistical Methods

Analyses were conducted using Stata 14 [36] and were intent-to-treat (ITT). Participants who did not complete the intervention end survey were censored from the analyses. Missing data also occurred within the intervention end survey when participants declined to answer a question. In almost all cases, less than 3% declined to answer an item. These responses were recoded as ‘failure’ for dichotomous measures (e.g., not tested for HIV) or to the sample mean for continuous measures. Income was the exception: 29% declined to provide an answer. It was kept as its own category.

Feasibility and acceptability were examined using the criteria articulated above. Next, logistic regression quantified the differences in dichotomous outcome measures by experimental arm. Because we anticipated the measure to be highly skewed, condom use was examined both as a dichotomous measure (i.e., ever versus never had sex with a condom during the intervention period) and as a count (i.e., the number of condom-protected sex acts during the intervention period). Poisson regression was used to estimate the relative difference in the number of condom-protected sex acts by experimental arm. Statistical significance was indicated if p ≤0.05; however, given the pilot nature of the work, marginally significant results (p ≤ 0.10) also were noted.

Given the difference in HIV rates by age and sex [4], both were entered as covariates in multivariate analyses. We also adjusted the models for mode of survey completion (i.e., on their own online or with staff over the telephone), and the baseline indicator of the outcome of interest (e.g., condom use). Characteristics that significantly differed by experimental arm at baseline despite randomization, and those that were significantly associated with condom use at baseline also were included in multi-variate analyses. Analyses were conducted for the whole sample, and again for those who were sexually experienced (i.e., sex in the past two years) at baseline.

Results

Participants were, on average, 20.2 years of age (SD: 1.3, Range: 18–22). About half (54%) were male sex and three in five (59%) lived outside of Kampala. One in three participants (37%) were currently working and one in three (34%) had an O-level education or lower. Seven in ten participants (72%) had ever had penile-vaginal sex; 65% had had penile-vaginal sex in the past 24 months. 2.5% (n = 5) had ever had penile-anal sex; 2% (n = 4) reported penile-anal sex in the past 24 months. Over nine in ten (92%) had ever been tested for HIV. As shown in Table 1, the control and intervention arms were generally well balanced on baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the ITG RCT sample (n = 202)

| Participant characteristics | Control (n = 101) | Intervention (n = 101) | Test statistic | p-value | Non-responder at intervention end (n = 35) | Responder at intervention end (n = 167) | Test statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M: SD) | 20.2 (1.3) | 20.3 (1.3) | t(200) = 0.54 | 0.59 | 20.2 (1.4) | 20.2 (1.3) | t(200) = −0.28 | 0.78 |

| Living in Kampala district | 45.5% (46) | 36.6% (37) | X2(1) = 1.66 | 0.20 | 37.1 (13) | 41.9 (70) | X2(1) = 0.27 | 0.60 |

| Currently working | 36.6% (37) | 36.6% (37) | NC | NC | 40.0% (14) | 35.9% (60) | X2(1) = 0.21 | 0.65 |

| Currently in school | 51.5% (52) | 58.4% (59) | X2(2) = 3.35 | 0.19 | 51.4% (18) | 55.7% (93) | X2(1) = 0.98 | 0.32 |

| Highest level of education | X2(4) = 4.86 | 0.30 | X2(4) = 6.6 | 0.16 | ||||

| Primary | 1.0% (1) | 3.0% (3) | 5.7% (2) | 1.2% (2) | ||||

| Ordinary level (O-level) | 35.6% (36) | 27.7% (28) | 28.6% (10) | 32.3% (54) | ||||

| Advanced level (A-level) | 48.5% (49) | 52.5% (53) | 40.0% (14) | 52.7% (88) | ||||

| Tertiary | 11.9% (12) | 8.9% (9) | 17.1% (6) | 9.0% (15) | ||||

| University | 3.0% (3) | 7.9% (8) | 8.6% (3) | 4.8% (8) | ||||

| Income | X2(6) = 6.73 | 0.35 | X2(6) = 1.8 | 0.93 | ||||

| Less than 50,000 shillings | 29.7% (30) | 33.7% (34) | 31.4% (11) | 31.7% (53) | ||||

| 50,000–100,000 shillings | 20.8% (21) | 14.9% (15) | 20.0% (7) | 17.4% (29) | ||||

| 100,001–200,000 shillings | 5.9% (6) | 14.9% (15) | 11.4% (4) | 10.2% (17) | ||||

| 200,001–300,000 shillings | 7.9% (8) | 7.9% (8) | 2.9% (1) | 9.0% (15) | ||||

| 300,001–500,000 shillings | 3.0% (3) | 2.0% (2) | 2.9% (1) | 2.4% (4) | ||||

| 500,001–1,000,000 shillings | 1.0% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.6% (1) | ||||

| Do not want to answer | 31.7% (32) | 26.7% (27) | 31.4% (11) | 28.7% (48) | ||||

| Relationship status | X2(5) = 1.33 | 0.93 | X2(5) = 7.8 | 0.17 | ||||

| Single, not dating | 40.6% (41) | 40.6% (41) | 45.7% (16) | 39.5% (66) | ||||

| Dating but not living with partner | 52.5% (53) | 52.5% (53) | 48.6% (17) | 53.3% (89) | ||||

| Living with partner | 4.0% (4) | 4.0% (4) | 0.0% (0) | 4.8% (8) | ||||

| Married | 1.0% (1) | 1.0% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 1.2% (2) | ||||

| Separated | 1.0% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 2.9% (1) | 0.0% (0) | ||||

| Do not want to answer | 1.0% (1) | 2.0% (2) | 2.9% (1) | 1.2% (2) | ||||

| Male sex | 52.5% (53) | 54.5% (55) | X2(1) = 0.08 | 0.78 | 40.0% (14) | 56.3% (94) | X2(1) = 3.09 | 0.08 |

| Gender identity | ||||||||

| Male | 53.5% (54) | 54.5% (55) | X2(1) = 0.02 | 0.89 | 40.0% (14) | 56.9% (95) | X2(1) = 3.32 | 0.07 |

| Female | 44.6% (45) | 43.6% (44) | X2(1) = 0.02 | 0.89 | 54.3% (19) | 41.9% (70) | X2(1) = 1.80 | 0.18 |

| Transwoman | 0.0% (0) | 1.0% (1) | X2(1) = 1.01 | 0.32 | 0.0% (0) | 0.6% (1) | X2(1) = 0.21 | 0.65 |

| Transman | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | NC | NC | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | NC | NC |

| Genderfluid | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | NC | NC | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | NC | NC |

| Other | 2.0% (2) | 2.0% (2) | NC | NC | 5.7% (2) | 1.2% (2) | X2(1) = 3.04 | 0.08 |

| Don’t understand the question | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | NC | NC | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | ||

| Sexual identity | ||||||||

| Straight/heterosexual | 41.6% (42) | 49.5% (50) | X2(1) = 1.28 | 0.26 | 40.0% (14) | 46.7% (78) | X2(1) = 0.52 | 0.47 |

| Gay | 2.0% (2) | 0.0% (0) | X2(1) = 2.02 | 0.16 | 0.0% (0) | 1.2% (2) | X2(1) = 0.42 | 0.52 |

| Lesbian | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | NC | NC | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | NC | NC |

| Bisexual | 1.0% (1) | 1.0% (1) | NC | NC | 0.0% (0) | 1.2% (2) | X2(1) = 0.42 | 0.52 |

| Pansexual | 2.0% (2) | 1.0% (1) | X2(1) = 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.0% (0) | 1.8% (3) | X2(1) = 0.64 | 0.42 |

| Queer | 0.0% (0) | 1.0% (1) | X2(1) = 1.01 | 0.32 | 0.0% (0) | 0.6% (1) | X2(1) = 0.21 | 0.65 |

| Asexual | 2.0% (2) | 6.9% (7) | X2(1) = 2.91 | 0.09 | 11.4% (4) | 3.0% (5) | X2(1) = 4.84 | 0.03 |

| I don’t understand this question | 24.8% (25) | 23.8% (24) | X2(1) = 0.03 | 0.87 | 28.6% (10) | 23.4% (39) | X2(1) = 0.43 | 0.51 |

| I don’t want to answer | 26.7% (27) | 15.8% (16) | X2(1) = 3.58 | 0.06 | 20.0% (7) | 21.6% (36) | X2(1) = 0.04 | 0.84 |

| Other | 0.0% (0) | 1.0% (1) | X2(1) = 1.01 | 0.32 | 0.0% (0) | 0.6% (1) | X2(1) = 0.21 | 0.65 |

| Sexual behaviors | ||||||||

| Ever had vaginal sex | 74.3% (75) | 69.3% (70) | X2(1) = 0.61 | 0.43 | 74.3% (26) | 71.3% (119) | X2(1) = 0.13 | 0.72 |

| Vaginal sex in the past 2 years | 65.4% (66) | 64.4% (65) | X2(1) = .02 | 0.88 | 68.6% (24) | 64.1% (107) | X2(1) = 0.26 | 0.61 |

| Ever tested for HIV | 92.1% (93) | 92.1% (93) | NC | NC | 88.6% (31) | 92.8% (155) | X2(1) = 0.71 | 0.40 |

| Ever tested for other STIs | 64.4% (65) | 56.4% (57) | X2(1) = 1.32 | 0.25 | 60.0% (21) | 60.5% (101) | X2(1) = 0.003 | 0.96 |

| Number of vaginal sex acts in the past 90 days (M: SD) | 2.2 (6.3) | 1.5 (3.1) | t(200) = 0.94 | 0.35 | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.9 (0.4) | t(200) = −0.68 | 0.50 |

| Number of sex acts with condoms in the past 90 days (M: SD) | 1.1 (2.8) | 1.0 (2.1) | t(200) = 0.32 | 0.75 | .8 (2.0) | 1.1 (2.5) | t(200) = −0.60 | 0.55 |

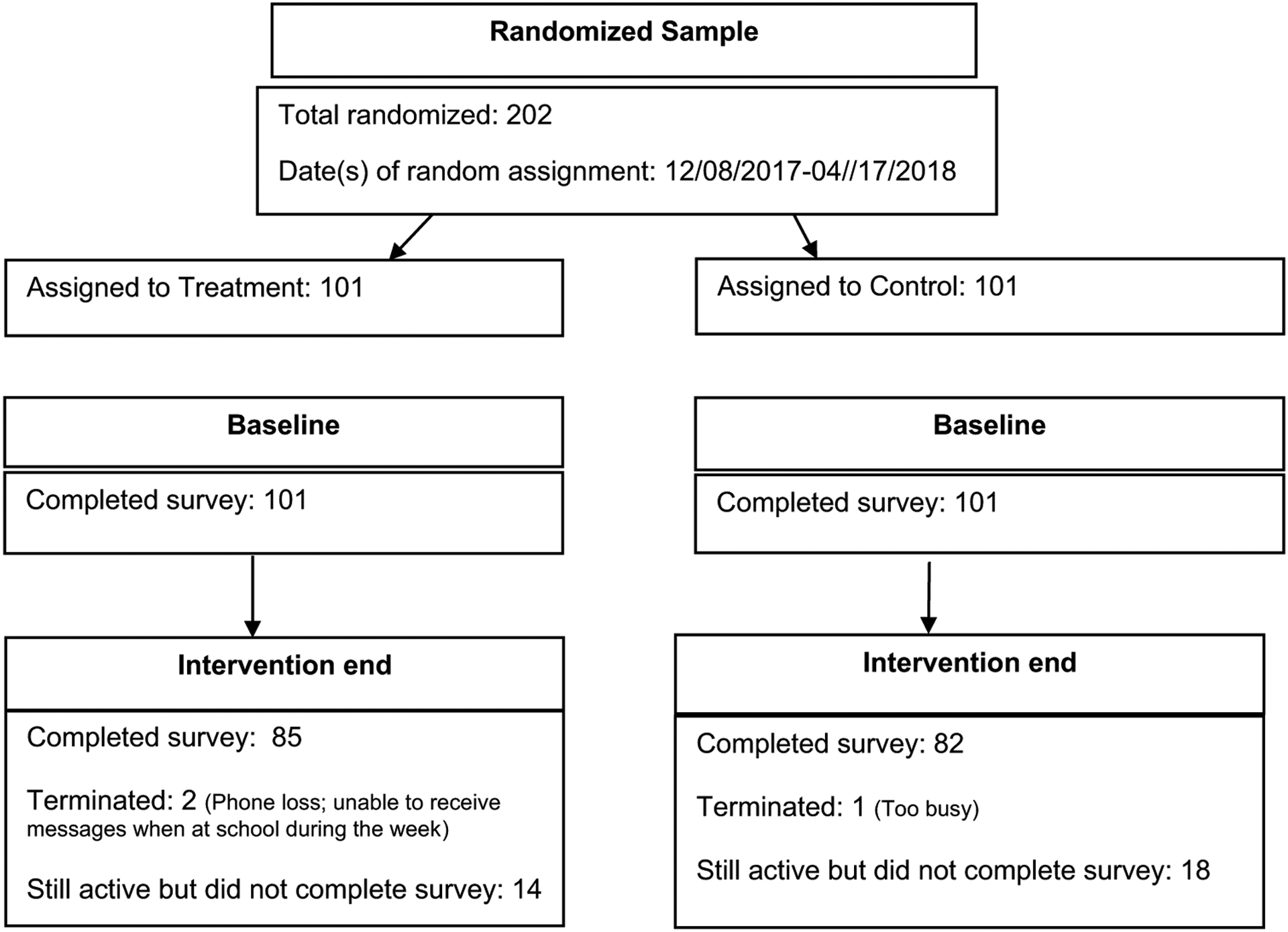

As shown in Fig. 1, follow-up response rates were similar by experimental arm: 84% of intervention (n = 85) and 81% (n = 82) of control participants responded at intervention end (χ2(1) = 0.31, p = 0.58). Those who were lost to follow-up versus those who were retained were mostly similar in their demographic characteristics and sexual behaviors (see Table 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram for InThistoGether (ITG) Pilot RCT

Condom use at baseline was associated with sexual identity: 35% of youth who reported using condoms at least once in the past 90 days identified as heterosexual compared to 49% of youth who reported not using condoms in the past 90 days (χ2(1) = 3.19, p = 0.07; Note that the reminder did not necessarily identify as non-heterosexual. There was a preponderance of young adults who said they did not understand the question). Similar differences were noted for working youth: 48% of youth who had used condoms at least once in the past 90 days at baseline were currently working compared to 32% of youth who had not used condoms (χ2(1) = 4.21, p = 0.04). Condom use also differed by relationship status (χ(5) = 9.29, p = 0.098) and income (χ(6) = 13.90, p = 0.03). Youth who had used condoms in the past 90 days also appeared to be older than youth who had not used condoms (t(200) = − 1.67, p = 0.097). As such, multivariate models adjusted for sexual identity, working status, relationship status, income, and age. The models also adjusted for sex, mode of survey completion, and baseline levels of the outcome of interest, the three of which, in addition to age, were prespecified.

No harms were reported in either experimental arm.

Feasibility

On average, 47.5 youth were randomized each month. Being higher than our pre-specified threshold of 35 per month, a hypothesis of feasibility was supported. Our response rate, 83%, was above the pre-specified threshold of 80%; this also supported a hypothesis of feasibility.

Acceptability

The percent of messages participants estimated that they read in the last week of the ‘core’ program averaged to 86% for intervention and 88% for control participants. Roughly four in five intervention (77%) and control (83%) participants who completed the intervention end survey said they read 80% or more of the messages over this time period. Thus, program engagement appears to be supported.

Three in five (61%; n = 50) intervention participants said that the daily text messages were their favorite program feature; 17% (n = 14) said the level up questions were their favorite. Fewer intervention participants rated badges (6%) or ITGenie as their favorite (7%). As shown in Table 2, all of the ITG intervention features were rated on average, above four on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 2.

ITG program acceptability (n = 167)

| Indicators of acceptability | Control (n = 82) | Intervention (n = 85) | Test statistic | p-value | Mean score from intervention participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability of the program | |||||

| How likely are you to recommend ITG to other young adults like you | 93.0 (80) | 96.6 (85) | χ2(1) = 1.13 | 0.29 | 4.8 (0.8) |

| My participation in ITG was valuable | 94.1 (79) | 97.7 (85) | χ2(1) = 1.45 | 0.23 | 4.8 (0.6) |

| The ITG program was too long | 57.1 (48) | 50.0 (43) | χ2(1) = 0.87 | 0.35 | 3.0 (1.5) |

| ITG will help Ugandan young adults learn how to prevent HIV and STDs | 100.0 (85) | 98.9 (86) | χ2(1) = 0.98 | 0.32 | 5.0 (0.2) |

| I learned things in ITG that will help me make decisions to prevent HIV and STDs | 96.5 (82) | 98.9 (86) | χ2(1) = 1.07 | 0.30 | 4.9 (0.5) |

| The information I learned in ITG was useful | 94.1 (80) | 98.9 (86) | χ2(1) = 2.86 | 0.09 | 4.9 (0.3) |

| ITG talked about condoms too much | 47.6 (40) | 66.7 (58) | χ2(1) = 6.34 | 0.01 | 3.7 (1.5) |

| ITG talked about sex too much | 57.1 (48) | 67.8 (59) | χ2(1) = 2.08 | 0.15 | 3.7 (1.5) |

| The ITG messages were easy to understand | 95.3 (81) | 97.7 (85) | χ2(1) = 0.74 | 0.39 | 4.8 (0.7) |

| ITG talked about things that my friends and I experience in our lives | 97.7 (83) | 97.7 (85) | χ2(1) = 0.001 | 0.98 | 4.8 (0.5) |

| ITG sent too many text messages | 43.5 (37) | 59.3 (51) | χ2(1) = 4.26 | 0.04 | 3.3 (1.6) |

| I stopped reading the text messages by the end of the program | 33.7 (28) | 47.1 (41) | χ2(1) = 3.16 | 0.08 | 2.9 (1.7) |

| ITG got in the way of my daily schedule | 42.4 (36) | 44.2 (38) | χ2(1) = 0.06 | 0.81 | 2.7 (1.7) |

| Acceptability of intervention features | |||||

| I liked ITGenie | 80.5 (70) | 4.9 (0.8) | |||

| ITGenie topics spoke to issues I was interested in | 77.0 (67) | 4.8 (1.0) | |||

| I liked the badges | 93.1 (81) | 4.6 (0.6) | |||

| The badges helped me carry condoms | 81.6 (71) | 4.3 (0.9) | |||

| The badges helped me use condoms more | 70.9 (61) | 4.7 (1.2) | |||

| The badges helped me get tested for HIV and STDs | 82.7 (72) | 4.8 (0.9) | |||

| I liked the “level up” questions | 98.9 (86) | 4.9 (0.4) | |||

| The “level up” questions made it easier to remember things from ITG | 98.9 (86) | 4.9 (0.3) |

Italicized values denote p < 0.10

Bold values denote p < 0.05

Seven of 13 items about the program experience were rated above four. For example, 99% said that ITG would help young adults prevent HIV/STDs. That said, 59% agreed that ITG sent too many messages and 67%, that ITG talked too much about condoms. Taken together, the content and program features met acceptability thresholds; program experience was mixed.

In most cases, program ratings for intervention and control participants were similar, suggesting that blinding of the control group was successful.

Sexual Behaviors

As shown in Table 3, at intervention end, five months post-randomization, the ITG intervention was associated with significantly higher rates of condom-protected vaginal sex in the past 90 days generally (aIRR = 1.82, p < 0.001), and among those who were sexually experienced at baseline specifically (aIRR = 1.68, p < 0.001). The relative odds of past 90-day HIV testing also were significantly higher for those in the intervention than control group (aOR = 2.41, p = 0.03); testing rates specifically among those who were sexually active in the past 2 years at baseline were elevated but not statistically significantly so (aOR = 1.75, p = 0.26). No significant differences were noted between the experimental arms when condom-protected sex was examined dichotomously, or for abstinence.

Table 3.

Preliminary outcomes for sexual behaviors at intervention end

| Sexual behaviors | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control % (n) | Intervention % (n) | OR /IRR | 95% CI | p-value | aOR /aIRR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| All youth (n = 167) | n = 82 | n = 85 | ||||||

| Ever condom use in the past 90 days (OR) | 43.9 (36) | 51.8 (44) | 1.37 | 0.75, 2.52 | 0.31 | 1.38 | 0.67, 2.83 | 0.38 |

| # of condom sex acts in the past 90 days (IRR)a | 1.6 (3.0) | 2.4 (4.4) | 1.53 | 1.23, 1.90 | < 0.001 | 1.82 | 1.44, 2.28 | < .001 |

| Abstinence (OR) | 40.2 (33) | 37.7 (32) | 0.90 | 0.48 1.67 | 0.73 | 1.08 | 0.47, 2.44 | 0.86 |

| HIV testing (OR) | 68.3 (56) | 82.4 (70) | 2.17 | 1.05, 4.48 | 0.04 | 2.41 | 1.11, 5.24 | 0.03 |

| Among those who were sexually active in the past 2 years at baseline (n = 110) | ||||||||

| Ever condom use in the past 90 days (OR) | 60.4 (32) | 63.2 (36) | 1.13 | 0.52, 2.43 | 0.76 | 1.05 | 0.47, 2.39 | 0.90 |

| # of condom sex acts in the past 90 days (IRR)a | 2.3 (3.5) | 3.2 (5.1) | 1.47 | 1.18, 1.82 | 0.001 | 1.68 | 1.34, 2.10 | < 0.001 |

| Abstinence (OR) | 17.0 (9) | 21.1 (12) | 1.30 | 0.50, 3.40 | 0.59 | 1.35 | 0.50, 3.67 | 0.55 |

| HIV testing (OR) | 73.6 (39) | 82.5 (47) | 1.69 | 0.68, 4.22 | 0.26 | 1.75 | 0.66, 4.64 | .26 |

Bold value denotes p < 0.05

Adjusted models included youth sex, age, income, sexual identity (heterosexual versus all others), work status, relationship status (dating versus all other), and whether the survey was completed online versus with staff

OR Odds ratio, IRR Incident rate ratio, aOR adjusted odds ratio, aIRR adjusted incident rate ratio

Mean (Standard Deviation)

Six participants reported a positive HIV test during the intervention.

Discussion

As the first comprehensive text messaging-based HIV prevention program developed and tested nationally among 18–22-year-old youth in sub-Saharan Africa, findings suggest InThistoGether (ITG) may have the potential to affect Ugandan youth HIV preventive behavior, at least in the short term. This includes condom use and HIV testing, but not abstinence. The lack of impact on abstinence may be reflective of the sex-positive focus of the intervention content. Similar to previous mHealth HIV prevention programs in Uganda [14, 15], ITG also appears to be feasible and largely acceptable. It may be that ITG is associated with behavior change when these earlier interventions were not because a level of comprehensiveness and/or intensity is needed to affect behavior change. Future research could examine dose–response impacts to identify the minimum level of mHealth programming needed to impact HIV preventive behaviors.

Findings related to HIV testing are particularly promising because testing is the first step towards treatment, and, where available, PrEP initiation [37, 38]. Moreover, several cohort studies have shown that people who are HIV positive decrease their risk behaviors once they are aware of their status [39–43]. With almost half of male Ugandans who are HIV positive unaware of their status [7], efforts to invigorate testing could have significant public health impact. Further research is needed to understand whether sustained, routine HIV testing could be affected by ITG. It also will be important to investigate whether those in both rural and urban areas are able to access testing, as well whether they are able to affect linkage to care if positive.

It bears noting that, although data are supportive of ITG’s feasibility and acceptability, two in three youth in the intervention said that the program talked about sex and condoms too much. Admittedly, it seems likely that a program such as this will necessarily need to talk about condoms and sex at length. Given that youth felt this way and nonetheless continued in the study suggests that the information may have been appraised useful even if overwhelming at times. At the same time, three in five intervention participants said that ITG sent too many messages and almost half said that they stopped reading the messages by the end of the program. Future research might explore different configurations that could potentially invigorate program engagement through the end of the five months. One possibility might be fewer messages over a longer period.

Limitations

Until the cost of technology becomes more affordable in Uganda, cell phone-based programs that are implemented at the national level – particularly those that have Internet components—will likely be skewed towards higher income populations. To ensure equity, researchers will need to be pay particular attention to recruiting lower income youth to ensure sufficient representation until the technology divide narrows. It also bears noting that social desirability was not assessed. It is possible that people over-reported HIV preventive behavior given the focus of the program. Efforts to reduce response bias were made, however, including the collection of data online and training of research staff to query sensitive questions in a non-judgmental manner. Moreover, any untruthful reporting was unlikely to have been differentially distributed across the experimental arms given indications that the control group was successfully blinded. Another limitation is that the program was only offered in English. Although English is an official language and the language used in schools [44], this likely skewed access to educated populations given that there are 40 indigenous languages in Uganda [45]. Future efforts should explore the possibility of adapting the intervention to other languages. Additionally, querying past 90-day behavior at 5 months resulted in measurement of behaviors after the ‘core’ content had been delivered but during the time when the latent and booster content were sent. This may have resulted in an under- or overestimation of the intervention impact. Future trials that include follow-up assessments well beyond the end of the intervention will address this issue. Finally, measurement of the behavioral outcomes was based upon self-report. Although extant research suggests self-report of HIV testing is valid [46–49], future research might explore alternative methods, such as photo-verification of HIV testing.

Conclusion

Data from this pilot study suggest that InThistoGether is both feasible and acceptable. Results also provide reason for optimism that ITG may be associated with HIV preventive behaviors, particularly increased condom use and HIV testing, at least for the five month intervention period. Next steps include testing the intervention in a fully powered RCT over a longer period of time. It also would be beneficial to explore partnerships with local stakeholders, such as the Ugandan Ministry of Health, Reproductive Health Uganda, and Uganda Cares, as they might contribute to the implementation and sustainability of ITG over time.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants and research team, particularly Emmanuel Kyagaba, Babra Akankunda, and Emilie Chen for their contributions to the study.

Funding

RESEARCH reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R34MH109296. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviation

- ITG

In This to Gether

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics Approval Chesapeake IRB (now Advarra IRB) and the Mbarara University Science and Technology Research Ethics Board reviewed and approved the protocol.

Consent to Participate Participants provided informed verbal and electronic consent to participate.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Country Comparisons - HIV/AIDS - adult prevalence rate. Central Intelligence Agency. The world Factbook. 2020. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/hiv-aids-adult-prevalence-rate/country-comparison. Accessed 29 Apr 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health (2018). Uganda population-based HIV impact assessment. Government of Uganda; https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/3430•PHIA-Uganda-SS_NEW.v14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Government of Uganda. HIV and AIDS Uganda Country Progress Report: 2013. Government of Uganda. 2014. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/UGA_narrative_report_2014.pdf. Accessed 29 Apr 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uganda Ministry of Health. Uganda AIDS Indicator Survey 2011. Published online 2012:238. http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/AIS10/AIS10.pdf.

- 5.Radcliff D Mobile in Sub-Saharan Africa: can world’s fastestgrowing mobile region keep it up? Mobility. Published 2018. https://www.zdnet.com/article/mobile-in-sub-saharan-africa-can-worlds-fastest-growing-mobile-region-keep-it-up/. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lester RT, Gelmon LJ, Plummer FA. Cell phones: tightening the communication gap in resource-limited antiretroviral programmes? AIDS. 2006;20:2237–44. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280108508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swahn MH, Braunstein S, Kasirye R. Demographic and psychosocial characteristics of mobile phone ownership and usage among youth living in the slums of Kampala, Uganda. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(5):600–3. 10.5811/westjem.2014.4.20879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siedner M, Haberer J, Bwana M, Ware N, Bangsberg D. High acceptability for cell phone text messages to improve communication of laboratory results with HIV-infected patients in rural Uganda: a cross-sectional survey study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12(1):56. 10.1186/1472-6947-12-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Velthoven MH, Brusamento S, Majeed A, Car J. Scope and effectiveness of mobile phone messaging for HIV/AIDS care: a systematic review. Psychol Health Med. 2012;18(2):182–202. 10.1080/13548506.2012.701310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horvath T, Azman H, Kennedy GE, Rutherford GW. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:009756. 10.1002/14651858.CD009756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bärnighausen T, Chaiyachati K, Chimbindi N, Peoples A, Haberer J, Newell M. Interventions to increase antiretroviral adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of evaluation studies. Lancet. 2011;11(12):942–51. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1838–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pop-Eleches C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, et al. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS. 2011;25(6):825–34. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834380c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamison J, Karlan DS, Raffler P. Mixed method evaluation of a passive MHealth sexual information texting service in Uganda. Economic Growth Center, Yale University. Discussion Paper No. 1025. 2013. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2272746. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chib A, Wilkin H, Hoefman B. Vulnerabilities in mHealth implementation: a Ugandan HIV/AIDS SMS campaign. Glob Health Promot. 2013;20(1 suppl):26–32. 10.1177/1757975912462419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shafii T, Stovel K, Davis R, Holmes K. Is condom use habit forming? Condom use at sexual debut and subsequent condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(6):366–72. 10.1097/00007435-200406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson A, Levin ML. AIDS knowledge, condom attitudes, and risk-taking sexual behavior of substance-abusing juvenile offenders on probation or parole. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11(5):450–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence JS, Scott CP. Examination of the relationship between African American adolescents’ condom use at sexual onset and later sexual behavior: implications for condom distribution programs. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8(3):258–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendriksen ES, Pettifor A, Lee SJ, Coates T, Rees H. Predictors of condom use among young adults in South Africa: the reproductive health and HIV research unit national youth survey. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1241–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shafii T, Stovel K, Holmes K. Association between condom use at sexual debut and subsequent sexual trajectories: a longitudinal study using biomarkers. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1090–5. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS. Reaching out to men and boys - Addressing a blind spot in the response to HIV. Joint United Nations; 2017. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/blind_spot_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ybarra ML, Agaba E, Chen E, Nyemara N. Iterative development of In This toGether, the first mHealth HIV prevention program for older adolescents in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2020. 10.1007/s10461-020-02795-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanyoro R The most visited websites in Uganda. Published 2014. https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/all/uganda.

- 24.Wikipedia contributors. Media in Uganda http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Media_in_Uganda.

- 25.Ybarra ML, Prescott TL, Phillips GL II, Parsons JT, Bull SS, Mustanski B. Ethical considerations in recruiting online and implementing a text messaging-based HIV prevention program with gay, bisexual, and queer adolescent males. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(1):44–9. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taves DR. Minimization: a new method of assigning patients to treatment and control groups. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1974;15(5):443–53. 10.1002/cpt1974155443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual-level change in HIV risk behavior. In: Peterson JL, DiClemente RJ, (eds.) Handbook of HIV Prevention. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press; 2000:3–55. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2000-07286-001&site=ehost-live. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS risk behavior. Psychol Bull. 1992. 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ybarra M, Goodenow C, Rosario M, Saewyc E, Prescott T. An mHealth intervention for pregnancy prevention for LGB teens: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020013607. 10.1542/peds.2020-013607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ybarra ML, Prescott T, Phillips GL III, Bull SS, Parsons JT, Mustanski B. Pilot RCT results of an mHealth HIV prevention program for sexual minority male adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017. 10.1542/peds.2016-2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ybarra ML, Holtrop JS, Prescott TL, Rahbar MH, Strong D. Pilot RCT results of stop my smoking USA: a text messaging-based smoking cessation program for young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(8):1388–99. 10.1093/ntr/nts339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodgers A, Corbett T, Bramley D, et al. Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tob Control. 2005;14(4):255–61. 10.1136/tc.2005.011577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ybarra ML, Prescott T, Mustanski B, Parsons J, Bull SS. Feasibility, acceptability, and process indicators for Guy2Guy, an mHealth HIV prevention program for sexual minority adolescent boys. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(3):417–22. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ybarra ML, Bull SS, Prescott TL, Birungi R. Acceptability and feasibility of CyberSenga: an internet-based HIV-prevention program for adolescents in Mbarara, Uganda. AIDS Care. 2014;26(4):441–7. 10.1080/09540121.2013.841837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gehan E Clinical trials in cancer research. Environ Health Perspect. 1979;32:31–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.StataCorp. 2015. Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakku-Joloba E, Pisarski EE, Wyatt MA, et al. Beyond HIV prevention: everyday life priorities and demand for PrEP among Ugandan HIV serodiscordant couples. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(1):e25225. 10.1002/jia2.25225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.PrEPWatch. Uganda. https://www.prepwatch.org/country/uganda/.

- 39.Doll LS, O’Malley PM, Pershing AL, Darrow WW, Hessol NA, Lifson AR. High-risk sexual behavior and knowledge of HIV antibody status in the San Francisco city clinic cohort. Health Psychol. 1990;9(3):253–65. 10.1037//0278-6133.9.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cleary PD, Van Devanter N, Rogers TF, et al. Behavior changes after notification of HIV infection. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(12):1586–90. 10.2105/ajph.81.12.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fox R, Odaka NJ, Brookmeyer R, Polk BF. Effect of HIV antibody disclosure on subsequent sexual activity in homosexual men. AIDS. 1987;1(4):241–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Griensven GJ, de Vroome EM, Tielman RA, et al. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody knowledge on high-risk sexual behavior with steady and nonsteady sexual partners among homosexual men. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(3):596–603. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coates TJ, Morin SF, McKusick L. Behavioral consequences of AIDS antibody testing among gay men. JAMA. 1987;258(14):1889. 10.1001/jama.1987.03400140051006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook 2021: Uganda. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/uganda/. Accessed 29 Apr 2021.

- 45.Sawe BE. What languages are spoken in Uganda? Published 2017. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-languages-are-spoken-in-uganda.html.

- 46.Fogel J, Zhang Y, Guo X, et al. Reliability of self-reported HIV status among African MSM screened for HPTN 075. In: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Jaffe A, Johnson ME. Reliability, sensitivity and specificity of self-report of HIV test results. AIDS Care. 2007;19(5):692–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mota RMS, Kerr LRFS, Kendall C, et al. Reliability of self-report of HIV status among men who have sex with men in Brazil. J Acqui Immun Defic Syndr. 2011;57(Supplement 3):S153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.An Q, Chronister K, Song R, et al. Comparison of self-reported HIV testing data with medical records data in Houston, TX 2012–2013. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(4):255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.