Abstract

Purpose:

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) is a serious complication associated with bisphosphonate therapy, but its epidemiology in the setting of oral bisphosphonate therapy is poorly understood. This study examined the prevalence of ONJ among persons receiving chronic oral bisphosphonate therapy.

Materials and Methods:

We mailed a survey to 13,946 members who received chronic oral bisphosphonate therapy as of 2006 within a large integrated healthcare delivery system in Northern California. Respondents who reported ONJ, exposed bone or gingival sores, moderate periodontal disease, persistent symptoms or complications following dental procedures were invited for examination or to have their dental records reviewed. ONJ was defined as exposed bone (>8 weeks) in the maxillofacial region in the absence of prior radiation therapy.

Results:

Among 8,572 survey respondents (71±9 years, 93% female), 2,159 (25%) reported pertinent dental symptoms. Of these 2,159 patients, 1,005 were examined and an additional 536 provided dental records. Nine ONJ cases were identified, representing a prevalence of 0.10% (95% CI 0.05–0.20%) among survey respondents. Five cases occurred spontaneously (three in palatal tori). Four cases occurred in prior extraction sites. Three additional patients had mandibular osteomyelitis (two following extraction and one with implant failure) but without exposed bone. Seven patients had bone exposure that did not fulfill criteria for ONJ.

Conclusion:

Osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in 1 in 952 survey respondents with oral bisphosphonate exposure (minimum prevalence 1 in 1,537 among entire mailed cohort). A similar number had select features concerning for ONJ that did not meet criteria. This study provides important data on the spectrum of jaw complications among patients with oral bisphosphonate exposure.

Keywords: osteonecrosis of the jaw, bisphosphonate, alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate

INTRODUCTION

Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), a rare condition characterized by exposed necrotic bone in the maxillofacial region in patients with bisphosphonate exposure,1 has received increasing attention since early reports were published in 2003.2, 3 The majority of cases have presented following invasive dental procedures that involve dentoalveolar bone manipulation, although spontaneous exposure of bone has also been observed.4–11 The exact etiologic mechanism(s) remain unclear but may relate in part to altered bone remodeling or local tissue effects in susceptible patients.12, 13 Over 90% of reported cases to date have occurred with intravenous bisphosphonate therapy where the prevalence is estimated in the range of 1–5% depending on treatment duration.7–11, 14 Early case series also identified approximately 5% of reported cases occurring in patients receiving oral nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate drugs,5, 6 one of the primary therapies for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures.

Limited data exist about ONJ risk with the oral nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, alendronate, risedronate and ibandronate.5, 6, 15–17 The largest series of oral bisphosphonate-related ONJ described 27 cases with a minimum of three years treatment, half presenting without a recognized inciting event.16 Two smaller series identified 20 cases combined, including 16 following invasive dental procedures and 7 due to denture trauma.18, 19 The current estimates of ONJ prevalence range from 0.001%−0.01% among oral-bisphosphonate-treated populations, based largely on data from Australia and Germany,8, 20–22 while systematic data from the U.S. are lacking. Given the increasing numbers of persons dispensed oral bisphosphonate drugs (exceeding 5.4 million for the U.S. in 2007),23 a better understanding of the epidemiology of ONJ and oral bisphosphonate therapy is critical. The Kaiser Permanente PROBE (Predicting Risk of Osteonecrosis with Bisphosphonate Exposure) study was conducted to determine the prevalence of and predictors for ONJ among a large community-based population with chronic oral bisphosphonate exposure. The current report focuses on our initial prevalence findings from a large cross-sectional survey with targeted exams.

METHODS

Source Population

Kaiser Permanente of Northern California is a large integrated healthcare delivery system that provides comprehensive care to 3.3 million members, representing more than one third of insured adults in the greater San Francisco Bay Area. Its diverse membership is generally representative of the surrounding local and statewide population, except for somewhat lower representation of the extremes of age and income.

Institutional Review Boards of the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute and the Food and Drug Administration approved the study. Additional informed consent was obtained from participants in the exam component of the study.

Identification of Target Population

Using retrospective pharmacy data, we initially identified all members age ≥21 years who received recent chronic oral nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates defined as ≥4 prescriptions in health plan pharmacy for alendronate, risedronate or oral ibandronate, with at least one prescription in 2006, and a total estimated treatment exposure period spanning at least one year. Persons with HIV infection, prior intravenous bisphosphonate therapy, oral cavity neoplasm using 2005 Cancer Registry data,24, 25 diagnosed dementia, or inability to understand English were excluded. Eligible individuals included those who were health plan members in January 2007 with continuous membership during the prior two years (allowing up to a 3 month membership gap), lived within 40 miles of one of the three exam centers (Kaiser Permanente Oakland, Santa Clara or South Sacramento Medical Centers), were ≤ 90 years old, and had not died or been admitted to hospice care. Survey mailings were conducted between April and June 2007, including a second mailing sent to initial non-respondents. The mailed questionnaire focused on demographic information, clinical history, dental symptoms and oral and bone health. The survey was administered by phone upon request.

Subject Recruitment, Clinical Examination and Oral Health Record Retrieval

The study cohort included all persons who completed the mailed questionnaire. As the surveys were returned, we identified respondents reporting any of the following oral problems (collectively referred to as “dental symptoms”) for telephone interview: exposed bone, ONJ, denture discomfort, moderate to severe periodontal disease, persistent gingival or palatal sores, or complications following invasive dental procedures since initiating bisphosphonate therapy (implant loosening or exposure, infection, persistent pain or delayed healing after tooth extraction or root canal), and pain, swelling, numbness or bleeding of the gingival tissues or jaws, or loosening of teeth that was current or lasting ≥ 1 month in the past year. Symptoms localizing only to the temporomandibular joint were not considered a pertinent dental symptom. Reported dental symptoms were verified by telephone interview and participants were then given the option to come in for a clinical examination or to give signed permission for review of their dental records. Hence, a low threshold was used to identify patients for examination or dental record review in order to increase the likelihood of finding cases of ONJ.

All clinical exams included inspection of the oral cavity by trained dentists, including teeth, gingiva, palate, maxilla and mandible for bone exposure, gingival sores, fistulae, non-healing extraction sites, visibly mobile or exposed dental implants, and infection or persistent pain. A dental history was obtained and all findings concerning for ONJ were evaluated by one maxillofacial surgeon (F.O.). Patients with exposed bone, concerning clinical findings or focal persistent pain after invasive dental procedures were also referred for evaluation and necessary treatment within the health plan.

Staging for bisphosphonate-related ONJ was based on the 2006 American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) criteria which required treatment with a bisphosphonate, exposed bone in the maxillofacial region lasting >8 weeks (documented during clinical follow-up and/or review of oral health records), and no radiation therapy involving the jaw.1 Stage 1 was characterized by exposed/necrotic bone with no symptoms or infection; Stage 2 by exposed/necrotic bone with pain and infection; and Stage 3 by evidence of Stage 2 plus pathologic fracture, extra-oral fistula, or osteolysis extending to the inferior border of the mandible. Cases with prior radiation therapy involving the jaw were considered osteoradionecrosis of the jaw.

Dental records were reviewed for eligible persons who were not examined and hospitalization and ambulatory care databases were searched between January 2006 – August 2008 for cases and potentially concerning diagnoses (ONJ, osteonecrosis, osteoradionecrosis, osteomyelitis of the jaw, oral cavity lesion, and jaw pain). While a specific ICD-9 code for ONJ was not available until late 2007, the centralization of oral surgery care and liaison with head and neck surgery departments across health plan medical centers facilitated systematic ascertainment of new ONJ cases within our health plan. Patients were also mailed a study letter one year later (Fall 2008) which provided a phone number to call if they wanted to report osteonecrosis of the jaw, severe jaw infection or non-healing after tooth extraction or dental implant in order to capture any missed cases.

Bisphosphonate Exposure

Oral bisphosphonate exposure was determined using health plan pharmacy databases with prescription records available from 1994–2008. The length of each prescription (pills dispensed and dosing interval) and exposure timeline were calculated for each participant similar to previous methods.26 Consecutive prescriptions were counted in the same continuous treatment interval if the gap between the end date of the first and the dispense date of the second was <60 days. If the gap was >60 days, the second prescription was considered the start of a new treatment interval. For each patient, we combined the continuous treatment intervals to calculate the total duration and also determined the total bisphosphonate days’ supply. Most bisphosphonate prescriptions (85%) provided a three month drug supply.

Statistical Approach

All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.1.3 (Cary, NC). A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered significant. Continuous variables were compared between subgroups using Student’s t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test; categorical variables were compared using chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Prevalence of ONJ was reported as point estimate with 95% confidence interval (CI) among respondents and stratified by duration of bisphosphonate therapy. We also calculated the frequency per 100,000 person-years of treatment with 95% CI. In a sensitivity analysis, we estimated the minimum prevalence of ONJ among patients with oral bisphosphonate exposure using the larger population denominator of all individuals (N = 13,835) who received the mailed survey.

RESULTS

We initially identified 31,680 eligible persons who met minimum treatment criteria, including at least one bisphosphonate prescription in 2006. We excluded 5,108 patients based on: intravenous bisphosphonate treatment (N=98), oral cavity neoplasm (N=81), no written or spoken English (N=2,185), diagnosed dementia (N=1,185), HIV infection (N=36), not meeting membership criteria (N=1,759), and death or admission to hospice care (N=650). Of the remaining 26,572 eligible patients, 13,946 lived within 40 miles of an exam center and were age 21–90 years old.

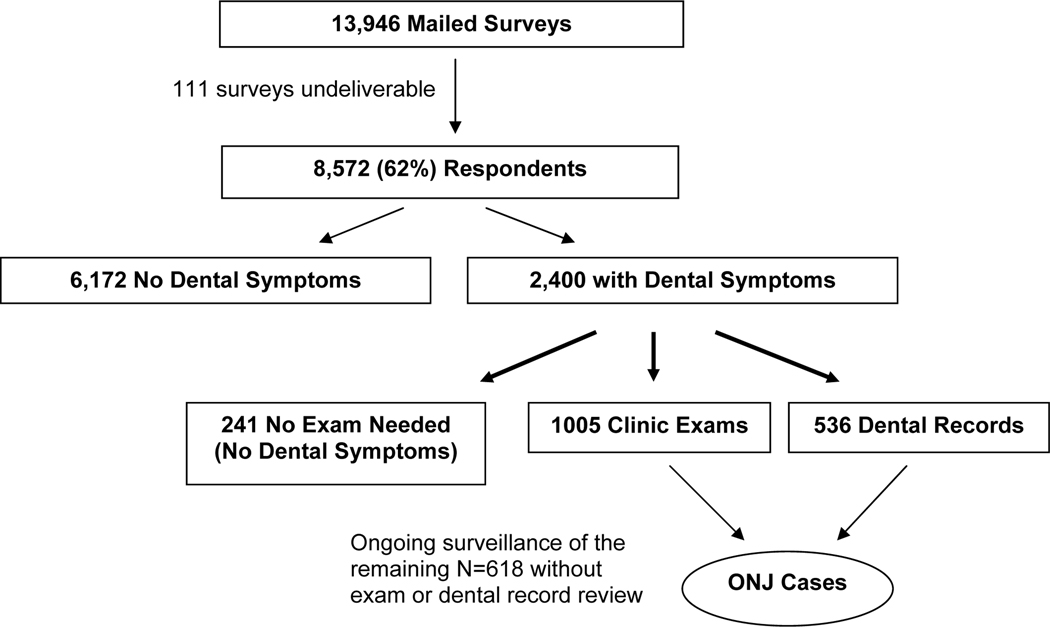

Among the 13,946 members who were mailed the questionnaire, 111 surveys were undeliverable, resulting in 13,835 survey recipients. Overall, 8,572 (62%) persons responded (Figure 1). Among the 2,400 respondents with dental symptoms, 2,354 (98%) telephone interviews were conducted, after which 241 patients were reclassified as having no concerning symptoms. Clinical exams were conducted in 1,005 symptomatic participants and an additional 536 provided dental records (96% had a dental assessment after January 2006). Among the 618 without dental records or study examination who had reported symptoms, 476 indicated on their survey that they had seen a dentist within the past year and 418 had evidence of continued oral BP therapy in 2008, suggesting a lower probability of bisphosphonate-related jaw issues.

Figure 1.

Recruitment and Examination of the PROBE Study Cohort

Identification of ONJ and ONJ-like Cases

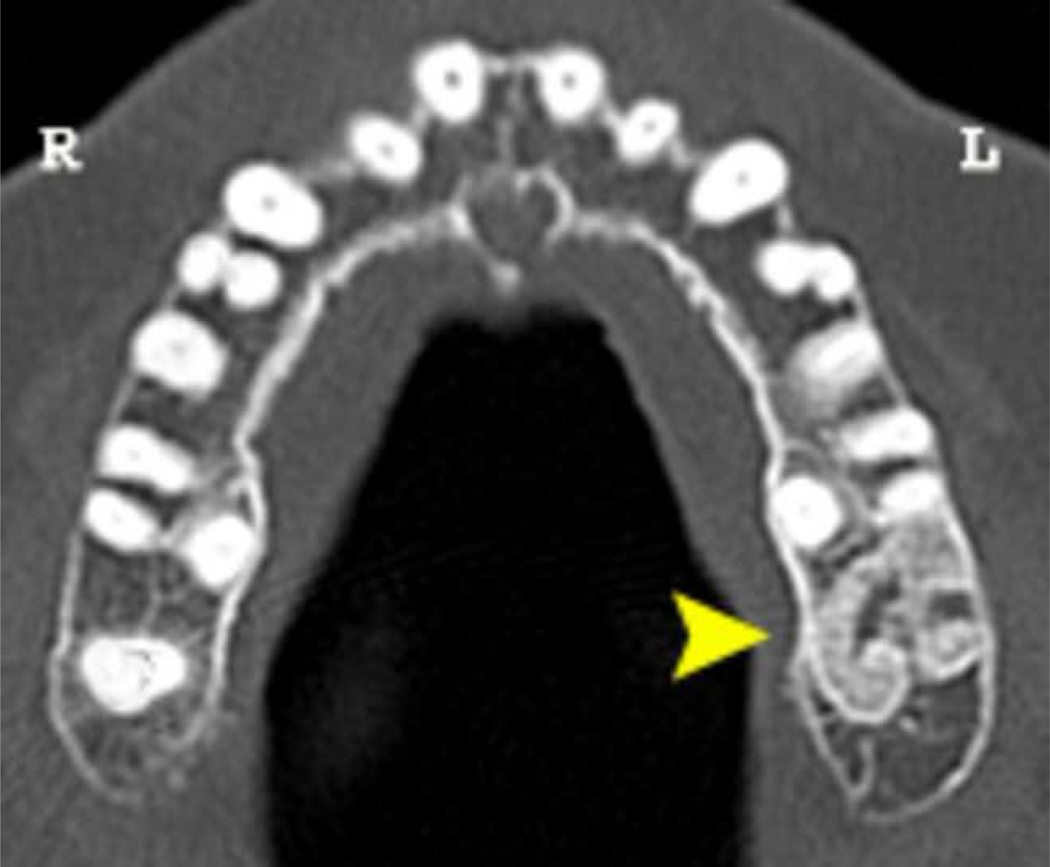

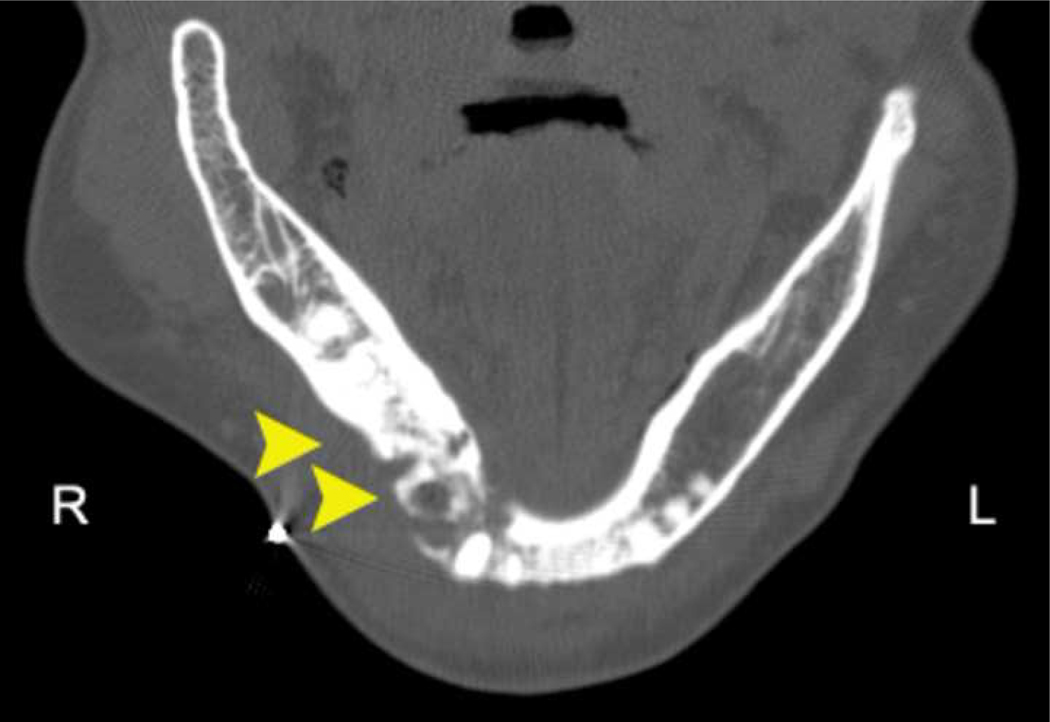

Nine cases of ONJ diagnosed in 2006–2008 were identified and described in Table 1, with ONJ severity ranging between Stage 1 and 2, and all visible lesions were ≤1 cm. Two cases were confirmed by detailed oral and maxillofacial surgery records since healing occurred before the survey mailing, while six were evaluated by and received care in Kaiser Permanente Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics. A final patient developed spontaneous ONJ with documented bone exposure eight months after initial study examination. Five of the nine cases developed ONJ spontaneously without a known antecedent. Among these, three had exposed bone on palatal tori and two developed spontaneous exposure of bone in the lingual mandible in areas without tori. Eventual healing occurred in two palatal cases following spontaneous exfoliation of the necrotic bone and one spontaneous mandible case with conservative management following cessation of bisphosphonate therapy. Four patients developed ONJ following tooth extraction (2 mandibular, 2 maxillary) despite initial superficial healing of the extraction site in two cases. Among these, the maxillary cases demonstrated small (<5 mm) lesions that improved with oral antibiotics, chlorhexidine rinses, and discontinuation of bisphosphonate therapy. We note that one patient also received chronic glucocorticoid therapy and had avascular necrosis of the hip after initial hip fracture repair. In contrast, the two mandibular cases did not respond to chlorhexidine rinses, local wound care amd multiple courses of long-term intravenous and/or oral antibiotics. Both patients ultimately required surgical debridement and sequestrectomy, at which time Actinomyces was found on histopathology. Radiographic findings of the four extraction-related cases were typical of ONJ, including sequestrum, osteosclerosis, and/or focal osteolysis with cortical disruption (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Identified Cases of Osteonecrosis of the Jaw and Predisposing Factors

| Case | Location | Stage | Size of Exposed Bone, Symptoms | Dental History and/or Predisposing Factors | BP Duration | One Year Outcome* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maxillary palatal torus | 1 | 2 × 2 mm, painless | Palatal torus | 4.9 years | Healed after exfoliation of exposed bone |

| 2 | Maxillary palatal torus | 2 | 4 × 6 mm, focal pain | Palatal torus | 3.0 years | Nearly healed |

| 3 | Maxillary palatal torus | 2 | 6 × 6 mm, focal pain | Palatal torus | 4.4 years | Healed after exfoliation of necrotic torus |

| 4 | Posterior Lingual Mandible | 1 | 12 mm (right), 3 mm (left), painless | None | 4.1 years | Healed |

| 5 | Lingual Mandible, midbody | 2 | 3 × 5 mm, focal pain | None | 4.3 years | Not healed |

| 6 | Posterior Lingual Mandible | 2 | 5 × 7 mm, swelling and purulence | Extraction 17 months prior with apparent healing Rheumatoid arthritis | 4.8 years | Not healed ** |

| 7 | Posterior Lateral Maxilla | 2 | 3 × 3 mm, focal pain and erythema | Extraction 11 months prior with apparent healing Rheumatoid arthritis, chronic glucocorticoid therapy, avascular necrosis of hip after hip fracture | 2.6 years | Not healed |

| 8 | Lateral Maxilla | 1 | 3 × 2 mm, painless | Extraction 8 months prior, healing status unclear | 6.0 years | Not healed |

| 9 | Lateral Mandible, parasymphysis | 2 | 5 × 5 × 16 mm fistula to bone with pain, swelling, purulence and paresthesia V3 | Extraction 14 months prior, never healed | 5.6 years | Not healed and worsening ** |

BP = bisphosphonate. Patients 3 and 4 were healed by the time they received the survey.

All cases met criteria of maxillofacial bone exposure persisting more than eight weeks with documentation by oral health care providers.

None continued bisphosphonate therapy.

Required long term antibiotics (>3 months) and ultimately surgical debridement

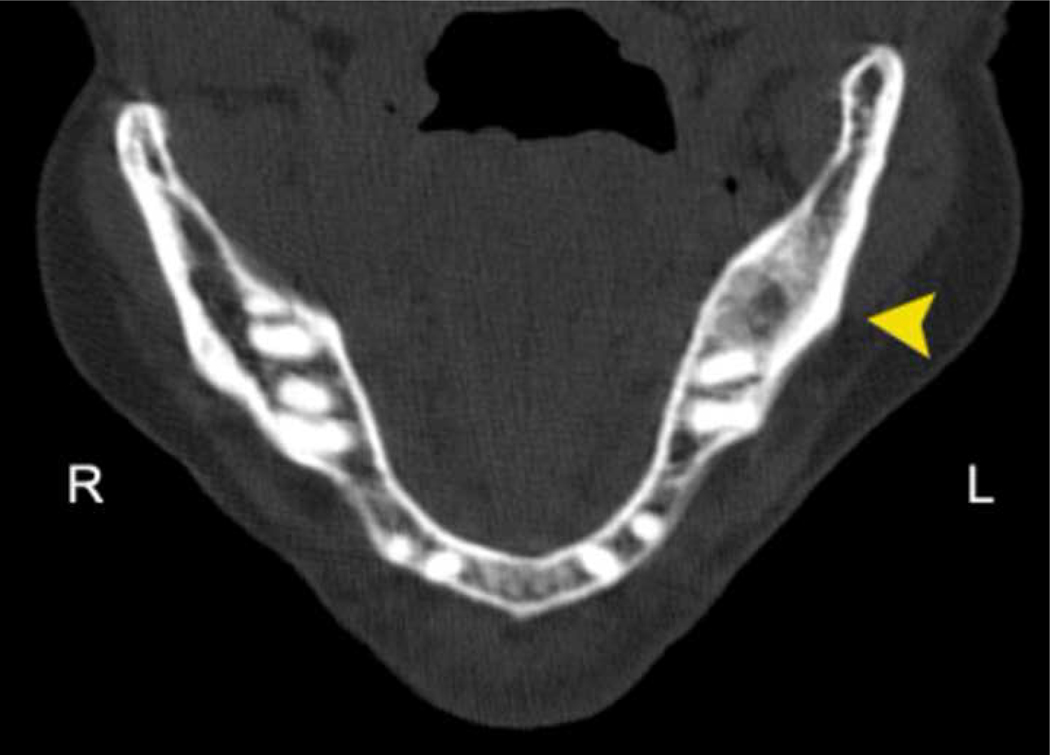

Figure 2. Radiographic Findings in Osteonecrosis of the Jaw after Dental Extraction.

Case 7: Axial CT showing an irregular area of bony sclerosis (12.5 mm x 9.3 mm) corresponding to the extraction site (maxillary molar extraction occurred 11 months prior to scan date).

Case 9a: Axial CT showing sclerosis with areas of lucency proximal to the extraction site (mandibular bicuspid extraction occurred 14 months prior to scan date). The lamina dura is thickened and sclerotic, and the extraction socket is still visible radiographically.

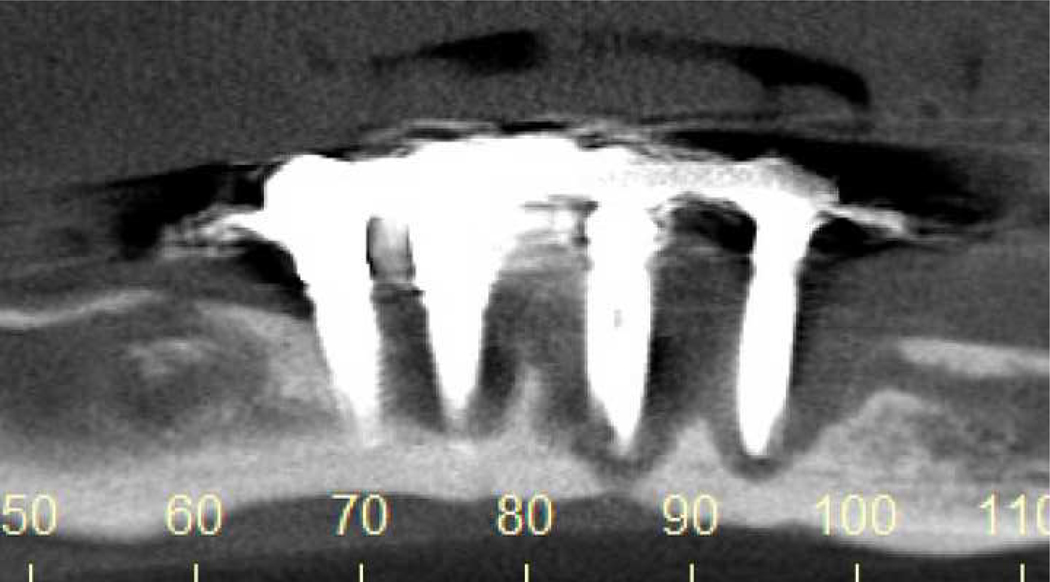

We additionally identified ten patients with ONJ-like features that did not meet ONJ criteria, many with abnormal radiographic findings (Table 2). Two patients had purulent osteomyelitis and intraoral fistulae that developed 5–10 months following mandibular molar extraction and a third patient had late failure (>4 years) of four anterior mandibular implants with associated osteomyelitis and extensive bone necrosis (Figure 3). Six patients had exposed bone that was transient, atypical, or related to bony sequestra, including two with contributory dental factors (denture wear and periodontal abscess), three with prior extraction (3–14 months prior) and one with chronic glucocorticoid therapy. The final patient had recurrent bony spicule formation and spontaneous tooth loss in a focal region that was found to have an osteolytic defect on panoramic radiography (Figure 3). Three participants whom we diagnosed with osteoradionecrosis were not included among these cases.

Table 2.

Osteonecrosis of the Jaw-like (ONJ-like) Cases that did not meet 2006 AAOMS Criteria for ONJ*

| Case | Location | Description | Radiographic Findings | Predisposing Factors | BP duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Mandible | Pain and paresthesia V3, non-healing extraction site with multiple fistulae and osteomyelitis. | Focal osteolytic region on panoramic x-ray | Extraction 5 months prior | 2.7 years |

| 11 | Mandible | Intermittent dull ache, purulence, fistula and osteomyelitis at prior extraction site | Osteosclerosis and focal radiolucency on CT | Extraction 10 months prior | 3.9 years |

| 12 | Mandible | Purulence, exposure and mobility of implants, osteomyelitis and extensive necrosis | Osteolysis and bone necrosis on CBCT | Late failure of implants placed over 4 years ago | 4.6 years |

| 13 | Mandible | 4 mm exposed bone < 6 wks | Osteosclerosis on CT | Partial denture | 4.4 years |

| 14 | Mandible | 3 mm exposed bone (<2.5 mos) adjacent to molar root | CT mandible unremarkable | Prednisone, azathioprine | 9.4 years |

| 15 | Mandible | 4 mm sequestrum x 4 weeks at prior extraction site. | Normal panoramic x-ray | Extraction 14 months prior | 4.3 years |

| 16 | Mandible | Pain and 3 mm sequestrum in prior extraction site. | Osteosclerosis on CT | Extraction 4 months prior | 11.1 years |

| 17 | Maxilla | 3 × 2 mm exposed bone x 1 year associated with periodontal abscess | Periodontal bone loss | Periodontal abscess | 4.7 years |

| 18 | Mandible | Pain with focal recurrent bony spicules over 1 year followed by spontaneous loss of adjacent tooth | Focal osteolytic region on panoramic x-ray | Tooth extraction >10 years prior | 3.0 years |

| 19 | Mandible | Pain with fistula (3 mo later), erythema, and bony spicule (7 mo later) in prior extraction site | Osteosclerosis on CT and intense focal uptake on bone scintigraphy | Extraction 3 months prior to initial presentation, diabetes mellitus | 3.8 years |

Imaging studies included panoramic radiography (x-ray, Cases 10, 13, 15, 18), cone-beam (CBCT, Case 12) or computed tomography (CT, Cases 11,12,13,14,16,19) with the exception of Case 17 where only periapical radiographs were available at the time of exposed bone.

Patients 15 and 17 were healed by the time they received the survey.

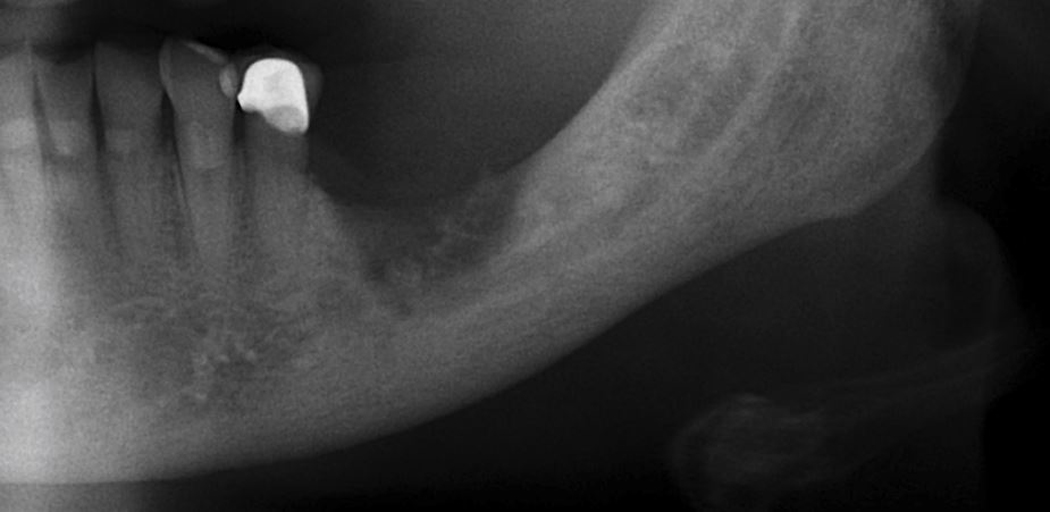

Figure 3. Radiographic Findings in Osteonecrosis of the Jaw-like (ONJ-like) Cases.

Case 12: Cone beam CT demonstrating severe osteolysis around 3 of 4 implants with sclerosis of the remaining bone to the inferior border of the mandible.

Case 16: Axial CT showing osteosclerosis surrounding an area of lucency corresponding to the extraction site (mandibular molar extraction occurred 4 months prior to scan date).

Case 18: Panoramic radiograph demonstrating a focal osteolytic defect with sclerosis of the surrounding bone and increased density of the left inferior alveolar canal. The patient reported a distant extraction history (>10 years ago) with recurrent bony spicules and spontaneous tooth loss in this region over the past year.

Patient Characteristics

We examined characteristics of the survey respondents by symptom status and characterized those with ONJ or ONJ-like findings (Table 3). The mean age was 71 years, with 93% women and 71% White. The median duration of oral nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate exposure was 3.5 (interquartile range IQR 2.5–4.7) years, with a median total days supply of 3.3 (IQR 2.4–4.5) years. The cumulative exposure was 32,678 person treatment years. Nearly all respondents (99.7%) had health plan pharmacy benefits in 2006 and over 85% of the cohort were continuous members for the last seven years (77% were members since 1995). There were no significant differences in gender and bisphosphonate exposure by symptom status, although age and race/ethnicity varied. As a group, patients with ONJ or ONJ-like findings were older and had longer treatment duration (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics of the PROBE Study Cohort

| Overall Cohort N=8,572 | Survey Response Category | Cases with ONJ or ONJ-like Features N = 19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| No Dental Symptoms N=6,413 | (+) Dental Symptoms N=2,159 | ||||

| Mean Age (years) | 71.0 ± 9.3 | 71.5 ± 9.3 | 69.6 ± 9.3* | 76.0 ± 6.8‡ | |

|

| |||||

| Female (%) | 93.0% | 92.8% | 93.8% | 94.7% | |

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity * | White (%) | 70.9% | 72.0% | 67.4% | 63.2% |

| Black (%) | 3.2% | 2.8% | 4.2% | 5.3% | |

| Hispanic (%) | 5.2% | 5.0% | 5.8% | 5.3% | |

| Asian (%) | 18.3% | 18.0% | 19.1% | 26.3% | |

| Other (%) | 1.8% | 1.5% | 2.6% | 0.0% | |

| Unknown (%) | 0.7% | 0.6% | 1.0% | 0.0% | |

|

| |||||

| Median Bisphosphonate Duration (years) | 3.5 (IQR 2.5 – 4.7) | 3.5 (IQR 2.5 – 4.7) | 3.5 (IQR 2.5 – 4.7) | 4.4 (IQR 3.8 – 4.9) † | |

|

| |||||

| Bisphosphonate (N): | Alendronate | 8503 | 6366 | 2137 | 19 |

| Risedronate | 258 | 187 | 71 | 1 | |

| Ibandronate (oral) | 34 | 25 | 9 | 0 | |

Age is expressed as mean ± standard deviation Bisphosphonate duration is expressed as median (interquartile IQR range).

p < 0.01 comparing those with and without dental symptoms

p < 0.05 or

p < 0.01 comparing those with and without ONJ or ONJ-like features

A systematic search of ambulatory and hospitalization databases for known ONJ cases and potentially concerning diagnoses (e.g., oral cavity lesion, jaw pain, osteoradionecrosis, osteomyelitis of the jaw or osteonecrosis) did not identify additional cases among all survey respondents. These efforts, coupled with patient interviews and follow-up mailing to cohort members one year following the mailed survey, reduce the likelihood of missed ONJ cases among symptomatic participants for whom we did not have dental records. There were also no cases of ONJ or concerning findings among 37 patients who self-reported or received intravenous bisphosphonate therapy after the cohort exclusion date.

Prevalence of ONJ among Oral Bisphosphonate-treated Patients

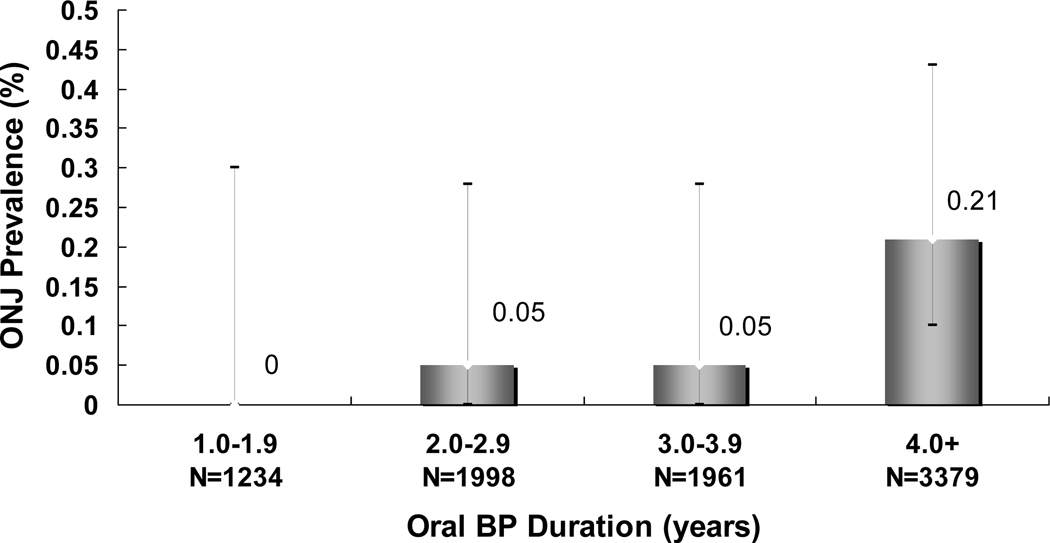

Among the 8572 survey respondents, the prevalence of ONJ was 0.10% (95% CI 0.05–0.20%), with a frequency of 28 (95% CI 14–53) per 100,000 person-years of oral bisphosphonate treatment. The minimum prevalence of ONJ among the larger population denominator of 13,835 individuals who received the mailed survey was 0.07% (95% CI 0.03–0.12%) assuming hypothetically no cases among non-respondents. When stratified by treatment duration (Figure 4), the prevalence of ONJ was greater among respondents with ≥4 years exposure compared with <4 years exposure (0.21% vs 0.04%, p=0.03). There were no cases reported among the 2193 cohort members with <2.5 years of treatment.

Figure 4. The Prevalence of Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (ONJ) by Duration of Bisphosphonate (BP) Therapy.

Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Among nearly 14,000 patients who received chronic oral bisphosphonate therapy, we identified at least nine cases of ONJ, yielding a minimum prevalence of 1 in 952 (0.10%) survey respondents or at least 1 in 1,537 (0.07%) in the target population of all those who received the mailed survey. Among survey respondents, we estimated a frequency of ONJ of 28 per 100,000 person-years of treatment. These estimates may be conservative because they do not include three cases of osteomyelitis without bone exposure. However, they do provide reassurance that the prevalence of oral bisphosphonate-related ONJ appears to be low, albeit higher than initially estimated.20, 21

Few studies have investigated the prevalence of ONJ in persons receiving exclusive oral bisphosphonate therapy. Merck & Co. reported no cases of ONJ among clinical trials involving ~17,000 patients (including 3000 patients with 3–5 years exposure and 800 patients with 8–10 years exposure) and estimated the worldwide reporting rate of ONJ to be <3 per 100,000 patient treatment years, regardless of etiology.27 However, non-systematic ascertainment of adverse dental outcomes during these clinical trials and the shortcomings of current post-marketing surveillance methods28, 29 limit the accuracy and generalizability of these estimates. In 2006, German investigators reported that ONJ prevalence among patients receiving oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis was 1 in 260,000, based on cases captured by a German Central Registry,20, 22 with follow-up data from this registry suggesting an increase in ONJ cases in this patient subset.30 These estimates contrast with an Australian study that identified ONJ cases through a nationwide maxillofacial surgeon survey (using prescription count to estimate the denominator of treated patients) and found that oral bisphosphonate-related ONJ occurred in 1 in 2,260 to 8,470 persons, depending on the subregion.8 Notably, the South Australian subregion which prospectively captured all cases through a single center had the highest prevalence of ONJ.8 Our study extends these findings by conducting both systematic case surveillance and ascertainment of cumulative bisphosphonate exposure. Using this approach, we found a slightly higher prevalence of ONJ among a contemporary, chronic oral bisphosphonate-treated population in this country.

There are several potential explanations for our higher observed prevalence. First, we studied persons receiving chronic oral bisphosphonate therapy since many discontinue treatment in the first year26 during which almost no cases have been reported. Second, there may be differences in bisphosphonate prescribing, dietary patterns, and oral health care among the different countries. Third, given that primary and subspecialty physicians were only recently aware of oral bisphosphonate-related ONJ and communication with dental providers was often not well established, we concentrated on direct patient query, clinical examination and dental record review, rather than relying only on electronic data and physician reporting for case ascertainment. Finally, we conducted screening exams among patients reporting suspicious dental issues to identify cases that had not yet come to medical attention.

Among our ONJ cases, the area of bone exposure was generally limited (2–10 mm), none were Stage 3, and some eventually healed. In general, cases that developed ONJ spontaneously were milder and the majority healed with conservative treatment. This contrasts with the more extensive ONJ cases reported in patients receiving chronic intravenous bisphosphonate therapy. Nearly half of our cases were temporally related to prior dental extractions and among these, two mandibular lesions progressed, required long-term antibiotics and surgical debridement. All four cases with prior extraction demonstrated radiographic features on computed tomography similar to those seen with intravenous bisphosphonate related ONJ.31–33

In this study, we also describe ten additional patients with selected ONJ-like features not meeting current ONJ criteria. Of interest, these included three patients with purulent mandibular osteomyelitis, two occurring in non-healing or previously healed extraction sites and one with late implant failure where clinical and radiographic bone necrosis and osteomyelitis supported the presumptive diagnosis of ONJ despite absence of bone exposure. Indeed, it has been suggested that bisphosphonate-related ONJ is more like osteomyelitis than aseptic osteonecrosis34 and some have grouped these conditions together for ONJ case ascertainment,30,35 particularly in the setting of bone necrosis.36 Because oral bisphosphonate drugs have less effective potency compared to intravenous bisphosphonates at doses used for skeletal malignancy, these cases were likely recognized before progression to overt bone exposure and are consistent with the observation that oral bisphosphonate-related ONJ is generally less severe and might resolve with early recognition and treatment.1, 8 The 2006 consensus definition of ONJ1 excludes these osteomyelitis cases and may not address the full spectrum of jaw complications seen in oral bisphosphonate treated patients.

Table 2 also describes select patients without overt ONJ who had localized pain, bony sequestra or spicules in recent or distant extraction sites with focal radiographic findings similar to those seen in osteomyelitis and ONJ (osteosclerosis, osteolysis, bony sequestra). Some have speculated whether these cases represent an earlier (at risk) precursor stage (e.g. Stage 0) warranting close follow-up for potential progression to ONJ,37–40 although the contributory role of other dental factors cannot be excluded.

The Kaiser Permanente PROBE Study is the largest cohort to date in which surveillance for ONJ has been systematically conducted among patients with exclusive oral bisphosphonate exposure. Although limited to northern California and primarily alendronate exposure, one of the strengths of our study is the inclusion of a diverse community-based population of nearly 14,000 individuals who received chronic bisphosphonate therapy from which a minimum prevalence of ONJ can be ascertained. We also leveraged Kaiser’s multiple automated databases for drug exposure and rapid ascertainment of key variables as well as for possible jaw-related complications or symptoms. This approach, along with screening examination and dental record review of symptomatic patients, allowed us to efficiently identify rare clinical outcomes where systematic examination of all patients was not feasible. Because there may have been inherent survey response bias and potential underestimation of ONJ with self-reported symptoms, we have also provided the minimum prevalence of ONJ within the broader population of those who received the mailed survey.

While bisphosphonate-naïve patients were not included for comparison, the diagnosis of ONJ (independent of radiation therapy, chemotherapy or maxillofacial trauma) remains extremely rare. This contrasts with the growing number of bisphosphonate-related ONJ cases reported in oral and maxillofacial surgery centers where it is now the major cause of diagnosed ONJ.5, 41 In 2004, Ruggiero et al. reported 63 patients with bisphosphonate-related ONJ diagnosed between 2001–2003, including six receiving exclusive oral bisphosphonate drugs, compared with only four in the prior three years without bisphosphonate exposure.5 Similarly we found no ONJ cases among the 2,193 with <2.5 years of treatment while the prevalence among those with ≥4 years treatment was as high as 0.21%. Although a better understanding of ONJ prevalence in an unexposed population is needed, these data and others8, 16 argue against the supposition that the ONJ cases observed simply reflect the expected rate of adverse dental outcomes in patients with dental or periodontal disease, independent of bisphosphonate treatment.

In conclusion, ONJ occurred in 1 in 952 participants who received chronic oral bisphosphonate therapy, with a minimum prevalence of at least 1 in 1,537 among the target population. The additional ONJ-like cases, especially osteomyelitis, suggest that the overall prevalence of jaw-related complications may be somewhat higher, albeit still extremely low compared to the risk of osteoporotic fracture among postmenopausal women. Hence, the net clinical benefit of oral bisphosphonate therapy remains high for the majority of patients with osteoporosis. However, these data support current guidelines recommending good oral hygiene, regular dental care,17, 21, 42 and enhanced patient and provider awareness for timely recognition of early stage disease.18,43 For patients who develop ONJ, initial management should include local conservative therapy and consideration of a drug holiday since oral bisphosphonate cessation may be associated with clinical improvement.16 This study also highlights the need for further research to identify clinical risk factors for ONJ, including comorbid conditions, pharmacologic exposures and dental factors that might impact treatment guidelines in patients receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank other members of the PROBE Study Team for their support: Donald Liberty DDS, Julia Townsend DDS, Sudheer Surpure DDS, Jeffrey Caputo DDS, Vicente Chavez DDS, A. Thomas Indresano DMD, David Baer MD, Pete Bogdanos, Alice Ansfield, Marvella Villasenor, Beatriz Monjaras, Joelle Ebalo, Benjamin Wang, Virginia Browning, Colanda Grier, Teresa Lin, Maryanne Armstrong, Mohammad Hararah and Joel Gonzalez. Our sincere appreciation to the Maxillofacial Clinics at Kaiser Permanente’s Oakland, Santa Clara and South Sacramento Medical Centers who facilitated the study visits and provided clinical evaluation of concerning cases. Finally, we are deeply grateful to the 8,572 study participants and their dentists whose support and contribution made this study possible.

Conflict of Interest: JLo previously received research funding from Novartis. DMartin previously owned stock in Merck. A household family member of NGordon previously owned stock in Novartis Pharmaceuticals. A non-household family member of FO’Ryan is employed by Roche Laboratories. AGo previously received research funding from Amgen and currently receives research funding from GlaxoSmithKline. The remaining authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources: This study was funded by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (HHSF223200510008C), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health (K12 HD052163), and the Kaiser Permanente Community Benefit Program. A portion of this study was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources at the National Institutes of Health (UCSF-CTSI UL1 RR024131).

Dr. Lo had full access to all the data for the study and has final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Food and Drug Administration or the National Institutes of Health. These data were presented in part at the 90th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society, San Francisco CA, June 15–18, 2008.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect he content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Mar 2007;65(3):369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Sep 2003;61(9):1115–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migliorati CA. Bisphosphanates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis. J Clin Oncol. Nov 15 2003;21(22):4253–4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, Broumand V. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Nov 2005;63(11):1567–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, Engroff SL. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. May 2004;62(5):527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo SB, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Narrative [corrected] review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Intern Med. May 16 2006;144(10):753–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badros A, Weikel D, Salama A, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in multiple myeloma patients: clinical features and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. Feb 20 2006;24(6):945–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavrokokki T, Cheng A, Stein B, Goss A. Nature and frequency of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws in Australia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Mar 2007;65(3):415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang EP, Kaban LB, Strewler GJ, Raje N, Troulis MJ. Incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma and breast or prostate cancer on intravenous bisphosphonate therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Jul 2007;65(7):1328–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pozzi S, Marcheselli R, Sacchi S, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: a review of 35 cases and an evaluation of its frequency in multiple myeloma patients. Leuk Lymphoma. Jan 2007;48(1):56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jadu F, Lee L, Pharoah M, Reece D, Wang L. A retrospective study assessing the incidence, risk factors and comorbidities of pamidronate-related necrosis of the jaws in multiple myeloma patients. Ann Oncol. Dec 2007;18(12):2015–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid IR. Osteonecrosis of the jaw: who gets it, and why? Bone. Jan 2009;44(1):4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B. Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment. Annu Rev Med. Oct 17 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoff AO, Toth BB, Altundag K, et al. Frequency and risk factors associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients treated with intravenous bisphosphonates. J Bone Miner Res. Jun 2008;23(6):826–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks JK, Gilson AJ, Sindler AJ, Ashman SG, Schwartz KG, Nikitakis NG. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with use of risedronate: report of 2 new cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. Jun 2007;103(6):780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marx RE, Cillo JE Jr., Ulloa JJ. Oral bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis: risk factors, prediction of risk using serum CTX testing, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Dec 2007;65(12):2397–2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dental management of patients receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy: expert panel recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. Aug 2006;137(8):1144–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yarom N, Yahalom R, Shoshani Y, Hamed W, Regev E, Elad S. Osteonecrosis of the jaw induced by orally administered bisphosphonates: incidence, clinical features, predisposing factors and treatment outcome. Osteoporos Int. Oct 2007;18(10):1363–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar SK, Meru M, Sedghizadeh PP. Osteonecrosis of the jaws secondary to bisphosphonate therapy: a case series. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9(1):63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felsenberg D. Osteonecrosis of the jaw--a potential adverse effect of bisphosphonate treatment. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. Dec 2006;2(12):662–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khosla S, Burr D, Cauley J, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. Oct 2007;22(10):1479–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook P, Olver I, Goss A. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Aust Fam Physician. Oct 2006;35(10):801–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verispan LLC. Vector One: Total Patient Tracker, Years 2002–2007. Data extracted 5–27-08 and 5–28-08. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oehrli MD, Quesenberry CP, Leyden W. Northern California Cancer Registry: 2007 Annual Report on Trends, Incidence, and Outcomes.: Kaiser Permanente, Northern California Cancer Registry; November 2007. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fireman BH, Quesenberry CP, Somkin CP, et al. Cost of care for cancer in a health maintenance organization. Health Care Financ Rev. Summer 1997;18(4):51–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo JC, Pressman AR, Omar MA, Ettinger B. Persistence with weekly alendronate therapy among postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(6):922–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Statement by Merck & Co., Inc. regarding Fosamax (alendronate sodium) and rare cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Product News [http://www.merck.com/newsroom/press_releases/product/fosamax_statement.html. Accessed July 30, 2008.

- 28.Fontanarosa PB, Rennie D, DeAngelis CD. Postmarketing surveillance--lack of vigilance, lack of trust. Jama. Dec 1 2004;292(21):2647–2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarassoff P, Csermak K. Avascular necrosis of the jaws: risk factors in metastatic cancer patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Oct 2003;61(10):1238–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung TI, von der Gablentz J, Hoffmeister B, et al. Osteonecrosis of jaw under bisphosphonate therapy: Patient profile and risk assessment. J Bone Miner Res. 2007. 2007:S298. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiandussi S, Biasotto M, Dore F, Cavalli F, Cova MA, Di Lenarda R. Clinical and diagnostic imaging of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. Jul 2006;35(4):236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phal PM, Myall RW, Assael LA, Weissman JL. Imaging findings of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. Jun-Jul 2007;28(6):1139–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raje N, Woo SB, Hande K, et al. Clinical, radiographic, and biochemical characterization of multiple myeloma patients with osteonecrosis of the jaw. Clin Cancer Res. Apr 15 2008;14(8):2387–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dodson TB, Raje NS, Caruso PA, Rosenberg AE. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 9–2008. A 65-year-old woman with a nonhealing ulcer of the jaw. N Engl J Med. Mar 20 2008;358(12):1283–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang J. ODS Postmarketing Safety Review. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Office, Food and Drug Administration, 2004. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/05/briefing/2005-4095B2_03_04-FDA-TAB3.pdf. [August 25, 2004; http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/05/briefing/2005-4095B2_03_04FDA-TAB3.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Junquera L, Gallego L. Nonexposed bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: another clinical variant? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Jul 2008;66(7):1516–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMahon RE, Bouquot JE, Glueck CJ, et al. Staging bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw should include early stages of disease. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Sep 2007;65(9):1899–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vieillard MH, Maes JM, Penel G, et al. Thirteen cases of jaw osteonecrosis in patients on bisphosphonate therapy. Joint Bone Spine. Jan 2008;75(1):34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagan JV, Jimenez Y, Diaz JM, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws in intravenous bisphosphonate use: Proposal for a modification of the clinical classification. Oral Oncol. Aug 18 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woo SB, Mawardi H, Treister N. Comments on “Osteonecrosis of the jaws in intravenous bisphosphonate use: Proposal for a modification of the clinical classification”. Oral Oncol. Nov 25 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walter C, Grotz KA, Kunkel M, Al-Nawas B. Prevalence of bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis of the jaw within the field of osteonecrosis. Support Care Cancer. Feb 2007;15(2):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bilezikian JP. Osteonecrosis of the jaw--do bisphosphonates pose a risk? N Engl J Med. Nov 30 2006;355(22):2278–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hellstein JW, Marek CL. Bisphosphonate osteochemonecrosis (bis-phossy jaw): is this phossy jaw of the 21st century? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. May 2005;63(5):682–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]