Abstract

The biosynthetic gene cluster of the aminocoumarin antibiotic coumermycin A1 was cloned by screening of a cosmid library of Streptomyces rishiriensis DSM 40489 with heterologous probes from a dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase gene, involved in deoxysugar biosynthesis, and from the aminocoumarin resistance gyrase gene gyrBr. Sequence analysis of a 30.8-kb region upstream of gyrBr revealed the presence of 28 complete open reading frames (ORFs). Fifteen of the identified ORFs showed, on average, 84% identity to corresponding ORFs in the biosynthetic gene cluster of novobiocin, another aminocoumarin antibiotic. Possible functions of 17 ORFs in the biosynthesis of coumermycin A1 could be assigned by comparison with sequences in GenBank. Experimental proof for the function of the identified gene cluster was provided by an insertional gene inactivation experiment, which resulted in an abolishment of coumermycin A1 production.

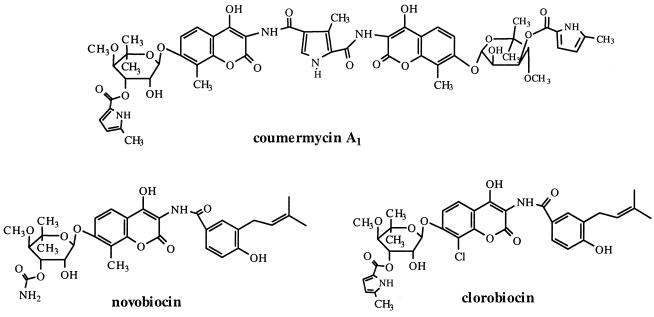

Coumermycin A1 is produced by Streptomyces rishiriensis DSM 40489 (13). Together with novobiocin and clorobiocin (Fig. 1), it belongs to the coumarin antibiotics. Novobiocin (Albamycin; Pharmacia & Upjohn) is licensed in the United States as an antibiotic for the treatment of infections with multiresistant gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus (27, 34, 47).

FIG. 1.

Structures of the coumarin antibiotics coumermycin A1, novobiocin, and clorobiocin.

Bacterial DNA gyrase is the target of the aminocoumarin antibiotics (25). X-ray crystallographic examinations (8, 20, 45, 48) have demonstrated that the aminocoumarin moiety and the substituted deoxysugar moiety of these compounds are essential for their binding to the gyrase B subunit of bacterial gyrase. The coumermycin A1 molecule (Fig. 1) contains two of these active aminocoumarin-deoxysugar moieties and has been shown to stabilize a dimer form of the 43-kDa fragment of GyrB (1, 10). Therefore, coumermycin A1 is likely to cross-link the two gyrase B subunits of the intact gyrase heterotetramer, which consists of two gyrase A and two gyrase B subunits. Consequently, the affinity of this antibiotic for intact gyrase is extremely high: 50% inhibition of gyrase is achieved by coumermycin A1 at a concentration of only 0.004 μM, compared to 0.1 μM for novobiocin, 1.8 μM for norfloxacin, and 110 μM for nalidixic acid (32). Likewise, coumermycin A1 has been found to exhibit much higher antibacterial activity than novobiocin (36).

In coumermycin A1, a methylpyrrole-2-carboxylic acid unit is attached to the 3-OH of each deoxysugar moiety (Fig. 1). The same pyrrole unit is also contained in clorobiocin (Fig. 1) and has been shown to result in a higher affinity for gyrase than has the carbamoyl group found in the corresponding position of novobiocin (45). In contrast, the prenylated 4-hydroxybenzoate group of novobiocin and clorobiocin, which is absent in coumermycin A1, appears not to be essential for biological activity (2, 11, 18). These features make coumermycin A1 a most interesting starting compound for the development of new aminocoumarin antibiotics, which may serve as anti-infective agents against multiresistant gram-positive bacteria. Recently, the chemical synthesis of a series of new aminocoumarin antibiotics has been published (9, 18, 19, 31, 33).

Combinatorial biosynthesis with the biosynthetic gene clusters for the aminocoumarin antibiotics could provide additional possibilities for the discovery of novel anti-infective agents. The genetic manipulation of the biosynthesis of polyketide and peptide antibiotics has already succeeded in the production of new and even clinically useful “hybrid” antibiotics (4, 14, 16, 26, 28, 39, 42).

Knowledge of the biosynthetic genes for aminocoumarin biosynthesis is a prerequisite for the production of new aminocoumarin antibiotics by combinatorial biosynthesis. Our group has recently reported the identification of the novobiocin biosynthetic gene cluster (41). Molecular biological studies of coumermycin A1 biosynthesis are yet unpublished. We present now the cloning and sequencing of the coumermycin A1 biosynthetic gene cluster from S. rishiriensis DSM 40489 and its functional identification by insertional gene inactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. rishiriensis DSM 40489 was cultivated at 28°C and 175 rpm for 2 to 4 days in baffled flasks. For isolation of chromosomal DNA, the organism was grown in liquid medium containing 1.0% malt extract, 0.4% yeast extract, 0.4% glucose, and 1.0 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.3). For preparation of protoplasts, S. rishiriensis was grown for 44 to 48 h in CRM medium, containing 10.3% sucrose, 2.0% tryptic soy broth, 1.0% MgCl2 · 6H2O, 1.0% yeast extract, and 0.4% glycine (pH 7.0). Protoplasts were prepared as described by Steffensky et al. (41) and regenerated on R2YE medium (12).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. rishiriensis DSM 40489 | Coumermycin A1 producer | DSMa |

| S. rishiriensis ZW20 | proB-disrupted mutant of S. rishiriensis DSM 40489 | This study |

| S. rishiriensis ZW21 | proB-disrupted mutant of S. rishiriensis DSM 40489 | This study |

| E. coli XL1 Blue MRF′ | Stratagene | |

| E. coli ET12567 | DNA methylase-negative strain | 23 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pOJ446 | Cosmid vector | 6 |

| pBluescript SK(−) | Cloning vector | Stratagene |

| pWHM249 | aphII neomycin resistance gene with the XhoI site eliminated | 22 |

| pNeo4 | aphII gene; the PstI and BamHI sites were eliminated by restriction of pWHM249 with the respective enzyme, blunting with DNA polymerase I, and religation | This study |

| pZW331 | 0.988-kb NotI-EcoRI fragment (positions 11700 to 12687 in sequence AF235050), cloned into the same sites of pBluescript SK(−); the insert contains the 5′ region of proB | This study |

| pZW32 | 2.844-kb EcoRI-BglII fragment (positions 12687 to 15530 in sequence AF235050), cloned into pBluescript SK(−) which had been digested with EcoRI and BamHI; the insert contains the 3′ region of proB | This study |

| pZW2 | 0.99-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment, containing the aphII gene from pNeo4, cloned in the same sites of pZW331 | This study |

| pZW3 | 0.96-kb HindIII-XhoI fragment from pZW32 cloned in the same sites of pZW2 | This study |

| pZK4 | 2.65-kb PstI fragment from pZW3 cloned in pBluescript SK(−); the orientations of proB and aphII were identical but were opposite that of bla | This study |

DSM, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen, Braunschweig, Germany.

For the production of coumermycin A1 and other secondary metabolites, wild-type and mutant strains of S. rishiriensis were cultured in 500-ml baffled flasks containing 100 ml of production medium (13), consisting of 3.5% Pharma Media (Hartge Ingredients GmbH & Co. KG, Hamburg, Germany), 3.0% glucose, 0.8% CaCO3, 1.0% KH2PO4, 0.2% yeast extract, 0.2% KCl, and 0.4% glycerol, at 28°C and 175 rpm for 7 to 10 days. For the cultivation of integration mutants, the medium was supplemented with 10 μg of neomycin per ml.

Escherichia coli XL1 Blue MRF′ and ET12567 were grown in liquid Luria-Bertani medium or on solid Luria-Bertani medium (1.5% agar) at 37°C (37).

Apramycin (100 μg/ml), carbenicillin (50 μg/ml), and neomycin (10 μg/ml for liquid media and 20 μg/ml for solid media) were used for selection of recombinant strains.

DNA isolation and manipulation.

Standard methods for DNA isolation and manipulation were performed as described by Hopwood et al. (12) and Sambrook et al. (37). DNA fragments were isolated from agarose gels using a QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Isolation of cosmids and plasmids was carried out with ion-exchange columns (Nucleobond AX kits; Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Construction and screening of the cosmid library.

Chromosomal DNA of S. rishiriensis DSM 40489 was partially digested with Sau3AI, dephosphorylated, ligated into cosmid vector pOJ446 (which had been digested with HpaI), dephosphorylated, and restricted with BamHI. The ligation products were packaged with Gigapack III XL (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany) and transduced into E. coli XL1 Blue MRF′.

A probe containing part of the dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase gene (novT) from the novobiocin producer Streptomyces spheroides was prepared as described previously (41). An additional probe (271 bp) was prepared by PCR from the novobiocin resistance gene (gyrBr) of S. spheroides using primers R1 (GACGGCTCCATCTTCGAGAC) and R2 (CGTCGGCGGCGATGGTGAC). For hybridization experiments, the probes were labeled with digoxigenin high prime DNA labeling and detection start kit II (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany).

DNA sequencing and computer-assisted sequence analysis.

Restriction fragments of approximately 300 to 3,000 bp from cosmids 4-2H and 4-7D were subcloned into pBluescript SK(−). Sequencing was performed by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method on a LI-COR automatic sequencer (MWG-Biotech AG, Ebersberg, Germany).

The DNASIS software package (version 2.1; Hitachi Software Engineering, San Bruno, Calif.) and the BLAST program (release 2.0) were used for sequence analysis and for homology searches in the GenBank database, respectively.

Construction of the vector for insertional gene inactivation.

Vector pZK4, for proB disruption, was constructed by insertion of neomycin resistance gene aphII into the sequence of proB as follows. The aphII gene was obtained as a 0.99-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from plasmid pNeo4 (Table 1) and ligated into the same sites of pZW331 (Table 1), which contained the 5′ region of proB, to give plasmid pZW2. The 3′ region of proB was obtained as a 0.96-kb HindIII-XhoI fragment from pZW32 (Table 1) and ligated into the same sites of pZW2, resulting in plasmid pZW3. A 2.65-kb PstI fragment of pZW3, containing the disrupted proB gene, was cloned into the same sites of pBluescript SK(−) to give the inactivation vector pZK4. In pZK4, the aphII gene fragment had the same orientation as the proB gene and the orientation opposite that of the bla resistance gene of the vector.

Transformation of S. rishiriensis DSM 40489.

Transformation of S. rishiriensis with pZK4 was carried out by polyethylene glycol-mediated protoplast transformation. Two grams of S. rishiriensis mycelia was incubated in 7 ml of P buffer (12) containing 1 mg of lysozyme per ml for 20 to 40 min at 30°C. For transformation, pZK4 was propagated in E. coli ET12567 (23), and the resulting double-stranded plasmid DNA was denaturated by alkaline treatment (30). The denaturated DNA (10 to 20 μg) was mixed with 200 μl of P buffer containing 109 S. rishiriensis protoplasts (200 μl) and with 500 μl of T buffer (12) containing 25% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 1000 (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). The resulting suspension was plated on R2YE plates. After 16 to 20 h at 25°C, the plates were overlaid with 3 ml of soft nutrient agar (12) containing neomycin (33.3 μg/ml) for selection of integration mutants.

Determination of the production of coumermycin A1 and other secondary metabolites in S. rishiriensis.

Metabolites of S. rishiriensis were analyzed by modifications of the methods of Kawaguchi et al. (13) and Berger and Batcho (5).

Bacterial cultures (100 ml) in coumermycin production medium (see above) were adjusted to pH 5 by the addition of formic acid and centrifuged. The pellet was extracted with 50 ml of a mixture of acetone and 1,4-dioxane (10:1) at room temperature for 2 h with stirring. After filtration, the supernatant was evaporated, and the residue was dissolved in 20 ml of 1 N ammonium hydroxide (pH 9). The solution was washed twice with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. The aqueous phase was adjusted to pH 5 by the addition of formic acid and extracted twice with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate phase was evaporated, and the residue was dissolved in 0.5 ml of 4 N ammonium hydroxide in methanol. Six microliters of this solution was applied to a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (Silica Gel 60 F254; E. Merck AG, Darmstadt, Germany). The plate was developed with dichloromethane-methanol-formic acid (45:2:1). Spots were visualized by spraying with 10% fresh ferric chloride-potassium ferricyanide (5 g each in 100 ml of water).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this study is available in the GenBank database under accession no. AF235050.

RESULTS

Cloning of the coumermycin A1 biosynthetic gene cluster.

We have previously cloned the novobiocin biosynthetic gene cluster from S. spheroides NCIB 11891 by screening of a cosmid library of the producer with a probe for a dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase gene, which is involved in the biosynthesis of the deoxysugar moiety of the antibiotic (41). Since coumermycin A1 contains the same deoxysugar moiety, we subjected genomic DNA of the coumermycin producer, S. rishiriensis DSM 40489, to Southern hybridization with the same probe. A single hybridizing band was detected. Likewise, hybridization with a probe from the novobiocin resistance gene gyrBr, encoding a non-novobiocin-sensitive gyrase B subunit (44), resulted in a single hybridizing band. Therefore, a cosmid library of the coumermycin producer was established in vector pOJ446 and screened with both probes.

The hybridizing cosmids were mapped by conventional restriction mapping as well as by hybridization of partial digests of the cosmids to pOJ446 vector sequences flanking the cosmid insert (35). In total, four different but overlapping cosmids which extended over a continuous 89-kb region of the S. rishiriensis DSM 40489 chromosome were identified.

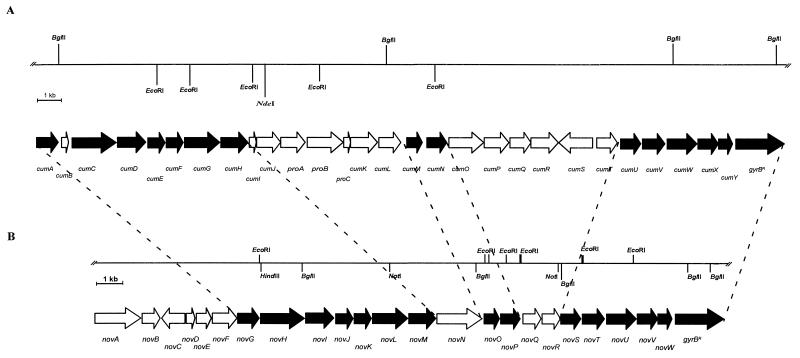

Sequencing of the cosmids and identification of ORFs.

From a core region of 30.8 kb, both strands were sequenced. This sequencing revealed the presence of 28 complete open reading frames (ORFs) upstream of the aminocoumarin resistance gene gyrBr (Fig. 2). The cluster showed striking similarity to the novobiocin biosynthetic gene cluster: 15 of the identified ORFs were found to have, on average, 84% identity to corresponding ORFs of the novobiocin cluster at the amino acid level (Table 2), and all of these ORFs were arranged in both clusters in identical order (Fig. 2). Table 2 shows the homologies found between the genes of the coumermycin A1 and novobiocin clusters, as well as homologies to other GenBank entries.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the biosynthetic gene clusters for coumermycin A1 (A) and novobiocin (B). The genes which are homologous in both clusters are shown as black arrows.

TABLE 2.

Identified ORFs in the biosynthetic gene cluster of coumermycin A1

| ORF | Size of product (amino acids [aa]) | Similar entity or entitiesa | % Identity of products | Origin | Nucleotide sequence accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cumA | 319 | novG (encoding 318 aa) | 77 | ||

| Regulatory protein (StrR) | 44 | Streptomyces griseus | P08076 | ||

| cumB | 71 | MbtH | 61 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | O05821 |

| cumC | 599 | novH (600 aa) | 80 | ||

| Peptide synthetase | 46 | Amycolatopsis orientalis | AJ223998 | ||

| cumD | 407 | novI (407 aa) | 88 | ||

| Cytochrome P-450 (NikQ) | 39 | Streptomyces tendae Tü901 | AJ250199 | ||

| cumE | 258 | novJ (262 aa) | 84 | ||

| 3-Ketoacyl-(ACP) reductase | 45 | Vibrio harveyi | P55336 | ||

| cumF | 245 | novK (244 aa) | 76 | ||

| Reductase | 32 | Klebsiella terrigena | Q04520 | ||

| cumG | 529 | novL (527 aa) | 80 | ||

| Acyl-CoA synthetase | 39 | Streptomyces coelicolor | AL049763 | ||

| cumH | 402 | novM (379 aa) | 79 | ||

| Glycosyltransferase | 44 | Streptomyces argillaceus | AF077869 | ||

| cumI | 95 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| cumJ | 355 | Acyltransferase (DpsC) | 38 | Streptomyces peucetius | L35560 |

| proA | 373 | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (PltE) | 46 | Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 | AF081920 |

| proB | 501 | Acyl-CoA synthetase (PltF) | 51 | Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 | AF081920 |

| proC | 89 | PltL | 38 | Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 | AF081920 |

| cumK | 399 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| cumL | 281 | Hydrolase | 31 | Pseudomonas fluorescens DSM 50106 | AF090329 |

| cumM | 230 | novO (230 aa) | 84 | ||

| Methyltransferase (LmbW) | 27 | Streptomyces linconensis | S44970 | ||

| cumN | 276 | novP (262 aa) | 88 | ||

| O-Methyltransferase | 53 | Micromonospora griseorubida | D16097 | ||

| cumO | 474 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| cumP | 377 | Decarboxylase | 36 | Streptomyces viridochromogenes | Y14337 |

| cumQ | 302 | PduX | 34 | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | AF026270 |

| cumR | 389 | Dehydrogenase | 39 | Neisseria meningitidis | U58911 |

| cumS | 491 | Resistance protein | 39 | Streptomyces alboniger | P42670 |

| cumT | 290 | Regulatory protein (TfdR) | 39 | Alcaligenes eutrophus | S80112 |

| cumU | 288 | novS (288 aa) | 81 | ||

| dTDP-4-keto-6-deoxyhexose reductase | 51 | Streptomyces griseus | P29781 | ||

| cumV | 336 | novT (336 aa) | 89 | ||

| dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase | 59 | Saccharopolyspora erythraea | L37354 | ||

| cumW | 420 | novU (420 aa) | 85 | ||

| C-Methyltransferase | 37 | Saccharopolyspora erythraea | X60379 | ||

| cumX | 296 | novV (297 aa) | 90 | ||

| dTDP-1-glucose synthase | 61 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | U55242 | ||

| cumY | 198 | novW (207 aa) | 82 | ||

| dTDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose 3,5-epimerase | 50 | Streptomyces griseus | P29783 | ||

| gyrB-cum | 677 | gyrB-nov (677 aa) | 91 | ||

| DNA gyrase B | 77 | Streptomyces coelicolor | P35886 |

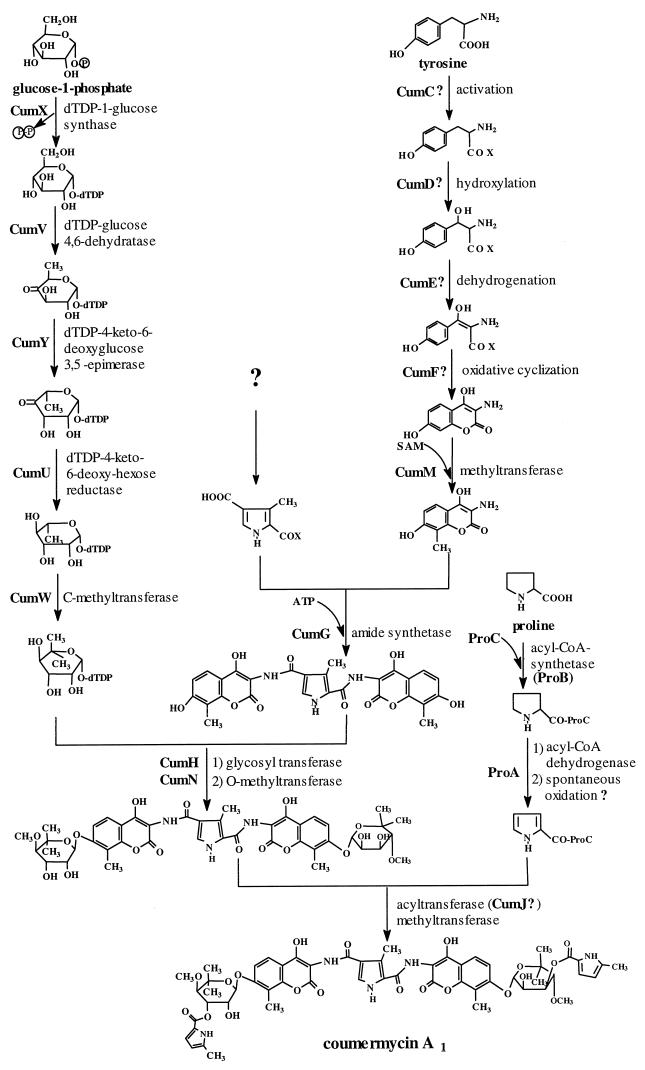

For the genes contained in the novobiocin cluster, a detailed discussion of their sequence homologies and their deduced functions has been given previously (41). proA, proB, and proC, for which no corresponding genes exist in the novobiocin cluster, show sequence similarities to pltE, pltF, and pltL, respectively. These genes are supposedly involved in the conversion of proline to pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid in pyoluteorin biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 (29). ProB, like PltF, belongs to the superfamily of the adenylate-forming enzymes and has been suggested to convert proline into an activated intermediate via an adenylation reaction. PltE, like ProA, shows homologies to flavin-dependent acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenases and is thought to catalyze the Δ2,3-dehydrogenation of an activated derivative of proline. The small ORFs proC and pltL (encoding 89 and 88 amino acids, respectively) show similarity to genes for acyl carrier proteins (ACP). Since coumermycin A1 contains two pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid moieties similar to the one found in pyoluteorin, it appears likely that the genes proA, proB, and proC are involved in the biosynthesis of these moieties, as tentatively depicted in Fig. 2. cumJ, immediately upstream of proA, shares homology with dpsC, which encodes an enzyme with acyltransferase activity (3). Therefore, cumJ was tentatively assigned to the transfer of the postulated activated pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid moieties to the 3-OH of the deoxysugar moieties (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Hypothetical biosynthetic pathway of coumermycin A1. CoA, coenzyme A.

Ten more ORFs for which no corresponding genes exist in the novobiocin cluster were identified in the coumermycin A1 cluster. Table 2 shows the homologies between these genes and other GenBank entries, but an assignment to coumermycin biosynthetic reactions would be purely speculative at present. cumS, which differs from all other genes by its orientation in the cluster (Fig. 2), shows homology to pur8, which confers resistance to puromycin (43); cumS may therefore be involved in resistance mechanisms.

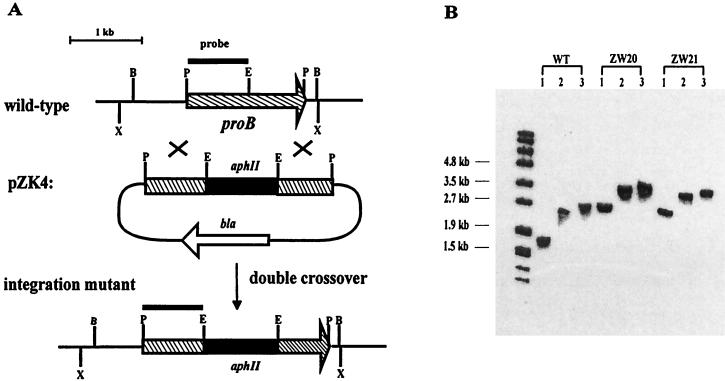

Insertional inactivation of the proB gene in S. rishiriensis.

The striking similarity between the gene cluster identified in this study and the previously identified gene cluster for novobiocin biosynthesis made it very likely that we had indeed cloned the coumermycin biosynthetic gene cluster. Functional proof for this hypothesis was provided by an insertional gene inactivation experiment. The gene proB, located in the central region of the cluster and possibly involved in pyrrole biosynthesis (see above), was chosen for this experiment.

An inactivation vector, pZK4, was constructed in which the structural gene proB was disrupted by insertion of a neomycin resistance gene (aphII, 0.99 kb; Fig. 4). The gene was introduced into S. rishiriensis by homologous recombination. After selection for the neomycin-resistant phenotype, mutant strains were analyzed by Southern hybridization. Two mutant strains, ZW20 and ZW21, which showed the desired gene replacement resulting from a double crossover, were identified (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Insertional gene inactivation in the coumermycin A1 biosynthetic gene cluster. (A) Schematic presentation of the gene replacement. The 0.87-kb DNA fragment used as a probe is indicated as a thin black bar. Relevant restriction sites: P, PstI; B, BamHI; X, XhoI; E, EcoRI. aphII, neomycin resistance gene. (B) Southern blot analysis of the proB mutants. Lanes 1, PstI; lanes 2, BamHI; lanes 3, XhoI. Expected bands: wild type (WT), 1.66 kb (PstI), 2.45 kb (BamHI), and 2.66 kb (XhoI); mutants resulting from gene replacement; 2.65 kb (PstI), 3.44 kb (BamHI), and 3.65 kb (XhoI).

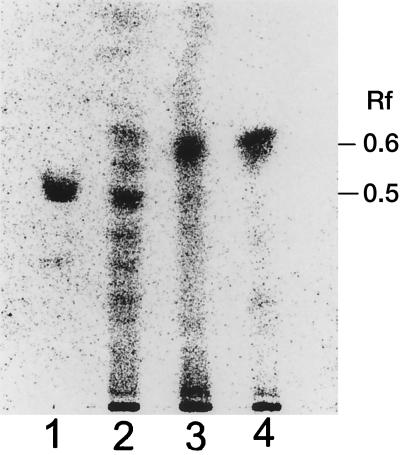

Culture extracts from the wild-type strain of S. rishiriensis and from the mutant strains, ZW20 and ZW21, were analyzed by TLC in comparison with a coumermycin A1 standard. While coumermycin A1 production in the wild-type strain of S. rishiriensis could be clearly detected, coumermycin A1 production in both mutants was completely abolished. The thin-layer chromatogram showed the accumulation of a new secondary metabolite in the proB-disrupted strains, clearly different from coumermycin A1 (Fig. 5). Structural identification of the new metabolite has not been successful so far, due to its instability.

FIG. 5.

TLC analysis of secondary metabolites in S. rishiriensis strains. Lane 1, coumermycin A1 standard; lane 2, extract of DSM 40489 (wild type); lanes 3 and 4, extracts of proB mutants ZW20 and ZW21, respectively. The plate (Silica Gel 60 F254) was developed with dichloromethane-methanol-formic acid (45:2:1). Blue spots on a yellow background were observed in daylight after spraying with 10% fresh ferric chloride-potassium ferricyanide (5 g each in 100 ml of water).

DISCUSSION

The coumarin antibiotics (Fig. 1) are closely related to each other in their chemical structure. The biosynthetic gene cluster of novobiocin, the best-known member of this group, has recently been identified (41). Coumermycin A1 is of special pharmaceutical interest due to its pronounced antibacterial activity and its extremely high affinity for bacterial gyrase (32, 36).

In the present study, we have cloned and sequenced the biosynthetic gene cluster of coumermycin A1 from S. rishiriensis DSM 40489. The cluster showed striking similarity to the novobiocin biosynthetic gene cluster (Fig. 2). In both clusters, nearly all of the ORFs are oriented in the same direction. At the 3′ end of each cluster, a gene encoding a coumarin-resistant gyrase B subunit is located. This gene has been described previously as the principal novobiocin resistance gene in the novobiocin producer S. spheroides (44), and expression of the gyrBr resistance gene from the coumermycin cluster in Streptomyces lividans showed that it also conferred resistance to both novobiocin and coumermycin A1 (E. Schmutz, unpublished data).

Immediately upstream of the resistance gene, both clusters contained five highly homologous genes in identical order (cumUVWXY and novSTUVW). Based upon their homology to known genes of deoxysugar biosynthesis, we previously assigned these genes to the first five steps required for the biosynthesis of the deoxysugar moiety of novobiocin (Fig. 1 and 3), and functional proof for this hypothesis was provided by an inactivation experiment with novT (41). Coumermycin A1 contains the same deoxysugar moiety as novobiocin, and in the coumermycin A1 biosynthetic gene cluster, exactly the same deoxysugar biosynthetic genes were found. This finding provides additional support to our functional assignment of these genes (Fig. 3).

One of the last steps of novobiocin biosynthesis is the O methylation of the 4-OH of the deoxysugar moiety, and we have putatively assigned the gene novP to this reaction. The same O-methylation reaction is required in coumermycin A1 biosynthesis; indeed, a gene homologous to novP, i.e., cumN, was found at the corresponding position of the coumermycin cluster. The gene novO, immediately upstream of novP, had been assigned to the C-methylation reaction at position 8 of the coumarin ring of novobiocin, and this assignment is now supported by the presence of a highly homologous gene, cumM, likely to carry out the same reaction in coumermycin biosynthesis.

Attachment of the deoxysugar to the 7-OH of the aminocoumarin ring requires very similar glycosyltransferases in novobiocin and coumermycin biosyntheses; indeed, two very similar glycosyltransferase genes, novM and cumH, are found at the same relative positions of both clusters.

In novobiocin (Fig. 1), the aminocoumarin ring and the substituted benzoate ring are linked by an amide bond. Recently, the gene novL has been functionally identified, by overexpression and purification, as encoding the amide synthetase responsible for both adenylation of the substituted benzoyl moiety and its transfer to the amino group (40). In the structure of coumermycin, two corresponding amide bonds are present, linking the two aminocoumarin rings to a central 3-methylpyrrole-2,4-dicarboxylic acid moiety. The gene cumG shows high homology to novL and is located at the same relative position of the gene cluster. It is most probably involved in the formation of these amide bonds. It cannot be decided at present, however, whether CumG catalyzes the adenylation and transferase reactions for the formation of both amide bonds in the coumermycin molecule or whether additional gene products are involved in these reactions.

The gene cumC displays distinct homology to peptide synthetase genes, and its deduced amino acid sequence shows the presence of the typical conserved motifs of peptide synthetases described by Marahiel et al. (24), including the 4-phosphopantetheinyl attachment site required for covalent binding of the acyl substrate in the form of a thioester (data not shown). cumC is very similar to novH, which is located at the same relative position of the novobiocin cluster. We have recently proven that novH is not involved in the formation of the amide bond between the aminocoumarin ring and the substituted benzoate ring of novobiocin, and we have speculated that NovH may catalyze the activation of tyrosine, or a derivative thereof, during the biosynthesis of one of the two aromatic rings of novobiocin (40). The presence of a very similar gene in the cluster for coumermycin, which contains the aminocoumarin gene but not the substituted benzoate ring, suggests that novH and the corresponding cumC may be involved in the biosynthesis of the aminocoumarin ring found in both antibiotics.

Immediately downstream of cumC is found the gene cumD, which shows homology to genes for cytochrome P-450 enzymes: the very recently described NikQ catalyzes the β-hydroxylation of histidine during nikkomycin biosynthesis (17), and the product of ORF20 of the chloroeremomycin biosynthetic gene cluster (46) may be involved in the β-hydroxylation of tyrosine (17). The biosynthesis of the aminocoumarin moieties of novobiocin and coumermycin, which are derived from tyrosine (15, 21), requires the introduction of an oxygen at the β-position of tyrosine. The cytochrome P-450 enzyme CumD and the corresponding enzyme NovI of the novobiocin cluster are likely candidates for the catalysis of this reaction.

The ring oxygen of the aminocoumarin moiety of novobiocin has been shown to be derived from the carboxy group of tyrosine, rather than from molecular oxygen (7), suggesting the formation of the aminocoumarin ring by a unique oxidative cyclization mechanism rather than by ortho-hydroxylation of tyrosine followed by simple lactonization. The formation of the aminocoumarin ring may therefore require the oxidation of a (hypothetical) β-hydroxytyrosine derivative to a β-ketotyrosine derivative and subsequent oxidative cyclization. CumE (and the corresponding NovJ) show homology to 3-ketoacyl-(ACP) reductase and may catalyze the first of the two oxidation steps. The adjacent CumF (and the corresponding NovK) share homology to redox enzymes and may catalyze the oxidative cyclization step.

The genes for the biosynthesis of the characteristic aminocoumarin ring of the aminocoumarin antibiotics must be present in both the novobiocin and the coumermycin clusters, and a comparison of both clusters is therefore an obvious method for identifying possible candidate genes for the biosynthesis of this moiety. This comparison leads to the suggestion that the gene products of cumCDEF corresponding to those of novHIJK may catalyze the formation of the aminocoumarin ring in a reaction sequence such as that shown in Fig. 3, i.e., activation of tyrosine and covalent binding in the form of a thioester, β-hydroxylation, oxidation to a β-ketoacyl intermediate, and oxidative cyclization. Further experiments are now in progress to provide functional proof for this hypothesis and to identify whether the C-methylation reaction catalyzed presumably by CumM (Fig. 3) occurs before or after coumarin ring formation. It is noteworthy that in the chloroeremomycin cluster, a gene with homology to a peptide synthetase gene, ORF19, is situated immediately upstream of the P-450 gene ORF20, suggesting that β-hydroxylation may require prior activation of tyrosine in the biosynthesis of chloroeremomycin as well. Likewise, β-hydroxylation of free histidine could not be demonstrated after heterologous expression of the P-450 enzyme NikQ mentioned above, and the involvement of an additional enzyme was postulated (17).

NovN has been suggested to catalyze the transfer of the carbamoyl group to the deoxysugar moiety of novobiocin (Fig. 1). Coumermycin does not contain this carbamoyl group, and no gene with similarity to novN is found in the coumermycin cluster. However, at the same relative position is found the gene cumJ, which shows homology to acyltransferase genes and which may catalyze the transfer of the pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid moieties to the deoxysugar moieties of coumermycin A1. Immediately downstream of cumJ are found the genes proA, proB, and proC, which share homology with genes supposedly involved in the conversion of proline to pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid in the biosynthesis of pyoluteorin in P. fluorescens Pf-5 (29). These genes may be tentatively assigned to the biosynthesis of the pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid moieties of coumermycin A1 (Fig. 3). The incorporation of proline into coumermycin A1 has been demonstrated previously (38). Further experiments are now in progress to elucidate the exact mechanism of the biosynthesis of these pyrrole rings.

For several other genes in the coumermycin cluster, so far no function can be suggested, e.g., for cumOPQRT. Some of these genes may be involved in the formation of the central 3-methylpyrrole-2,4-dicarboxylic acid unit of coumermycin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. R. Hutchinson for providing plasmid pWHM249, A. Bechthold for supplying the cosmid vector pOJ446, W. Wohlleben for providing the strain E. coli ET12567, and A. Mühlenweg for preparing the hybridization probe for gyrB. W. Wohlleben, A. Bechthold, and coworkers provided important technical advice for this project.

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to L. Heide and S.-M. Li).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali J A, Jackson A P, Howells A J, Maxwell A. The 43-kilodalton N-terminal fragment of the DNA gyrase B protein hydrolyzes ATP and binds coumarin drugs. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2717–2724. doi: 10.1021/bi00061a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Althaus I W, Dolak L, Reusser F. Coumarins as inhibitors of bacterial DNA gyrase. J Antibiot. 1988;41:373–376. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao W, Sheldon P J, Hutchinson C R. Purification and properties of the Streptomyces peucetius DpsC β-ketoacyl:acyl carrier protein synthase III that specifies the propionate-starter unit for type II polyketide biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9752–9757. doi: 10.1021/bi990751h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley R, Bennett J W. Constructing polyketides: from collie to combinatorial biosynthesis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:411–446. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger J, Batcho A D. Coumarin-glycoside antibiotics. J Chromatogr. 1978;15:101–158. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bierman M, Logan R, O'Brien K, Seno E T, Nagaraja Rao R, Schoner B E. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene. 1992;116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunton C A, Kenner G W, Robinson M J T, Webster B R. Experiments related to the biosynthesis of novobiocin and other coumarins. Tetrahedron. 1963;19:1001–1010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celia H, Hoermann L, Schultz P, Lebeau L, Mallouh V, Wigley D B, Wang J C, Mioskowski C, Oudet P. Three-dimensional model of Escherichia coli gyrase B subunit crystallized in two-dimensions on novobiocin-linked phospholipid films. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:618–628. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferroud D, Collard J, Klich M, Dupuis-Hamelin C, Mauvais P, Lassaigne P, Bonnefoy A, Musicki B. Synthesis and biological evaluation of coumarincarboxylic acids as inhibitors of gyrase B. l-Rhamnose as an effective substitute for l-noviose. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:2881–2886. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gormley N A, Orphanides G, Meyer A, Cullis P M, Maxwell A. The interaction of coumarin antibiotics with fragments of the DNA gyrase B protein. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5083–5092. doi: 10.1021/bi952888n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooper D C, Wolfson J S, McHugh G L, Winters M B, Swartz M N. Effects of novobiocin, coumermycin A1, clorobiocin, and their analogs on Escherichia coli DNA gyrase and bacterial growth. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;22:662–671. doi: 10.1128/aac.22.4.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces—a laboratory manual. Norwich, England: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawaguchi H, Tsukiura H, Okanishi M, Miyaki T, Ohmori T, Fujisawa K, Koshiyama H. Studies on coumermycin, a new antibiotic. I. Production, isolation and characterization of coumermycin A1. J Antibiot Ser A. 1965;18:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khosla C. Combinatorial biosynthesis of “unnatural” natural products. In: Gordon E M, Kerwin J F, editors. Combinatorial chemistry and molecular diversity in drug discovery. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1998. pp. 401–417. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kominek L A, Sebek O K. Biosynthesis of novobiocin and related coumarin antibiotics. Dev Ind Microbiol. 1974;15:60–69. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konz D, Marahiel M A. How do peptide synthetases generate structural diversity? Chem Biol. 1999;6:R39–R48. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauer B, Russwurm R, Bormann C. Molecular characterization of two genes from Streptomyces tendae Tü901 required for the formation of the 4-formyl-4-imidazolin-2-one-containing nucleoside moiety of the peptidyl nucleoside antibiotic nikkomycin. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:1698–1706. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laurin P, Ferroud D, Klich M, Dupuis-Hamelin C, Mauvais P, Lassaigne P, Bonnefoy A, Musicki B. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of novel highly potent coumarin inhibitors of gyrase B. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:2079–2084. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laurin P, Ferroud D, Schio L, Klich M, Dupuis-Hamelin C, Mauvais P, Lassaigne P, Bonnefoy A, Musicki B. Structure-activity relationship in two series of aminoalkyl substituted coumarin inhibitors of gyrase B. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:2875–2880. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis R J, Singh O M P, Smith C V, Skarzynski T, Maxwell A, Wonacott A J, Wigley D B. The nature of inhibition of DNA gyrase by the coumarins and the cyclothialidines revealed by X-ray crystallography. EMBO J. 1996;15:1412–1420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li S-M, Hennig S, Heide L. Biosynthesis of the dimethylallyl moiety of novobiocin via a non-mevalonate pathway. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2717–2720. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lomovskaya N, Fonstein L, Ruan X, Stassi D, Katz L, Hutchinson C R. Gene disruption and replacement in the rapamycin-producing Streptomyces hygroscopicus strain ATCC 29253. Microbiology. 1997;143:875–883. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacNeil D J, Gewain K M, Ruby C L, Dezeny G, Gibbons P H, MacNeil T. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene. 1992;111:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90603-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marahiel M A, Stachelhaus T, Mootz H D. Modular peptide synthetases involved in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2651–2673. doi: 10.1021/cr960029e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maxwell A. DNA gyrase as a drug target. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:102–109. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(96)10085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDaniel R, Thamchaipenet A, Gustafsson C, Fu H, Betlach M, Betlach M, Ashley G. Multiple genetic modifications of the erythromycin polyketide synthase to produce a library of novel “unnatural” natural products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1846–1851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montecalvo M A, Horowitz H, Wormser G P, Seiter K, Carbonaro C A. Effect of novobiocin-containing antimicrobial regimens on infection and colonization with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:794. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mootz H D, Marahiel M A. Design and application of multimodular peptide synthetases. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(99)80062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nowak-Thompson B, Chaney N, Wing J S, Gould S J, Loper J E. Characterization of the pyoluteorin biosynthetic gene cluster of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2166–2174. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2166-2174.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh S-H, Chater K F. Denaturation of circular or linear DNA facilitates targeted integrative transformation of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): possible relevance to other organisms. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:122–127. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.122-127.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peixoto C, Laurin P, Klich M, Dupuis-Hamelin C, Mauvais P, Lassaigne P, Bonnefoy A, Musicki B. Synthesis of isothiochroman 2,2-dioxide and 1,2-benzooxathiin 2,2-dioxide gyrase B inhibitors. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:1741–1745. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng H, Marians K J. Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV: purification, characterization, subunit structure, and subunit interactions. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24481–24490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Periers A-M, Laurin P, Ferroud D, Haesslein J-L, Klich M, Dupuis-Hamelin C, Mauvais P, Lassaigne P, Bonnefoy A, Musicki B. Coumarin inhibitors of gyrase B with N-propargyloxy-carbamate as an effective pyrrole bioisostere. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:161–165. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00654-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raad I I, Hachem R Y, Abi-Said D, Rolston K V I, Whimbey E, Buzaid A C, Legha S. A prospective crossover randomized trial of novobiocin and rifampin prophylaxis for the prevention of intravascular catheter infections in cancer patients treated with interleukin-2. Cancer. 1998;82:403–411. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980115)82:2<412::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redenbach M, Ikeda K, Yamasaki M, Kinashi H. Cloning and physical mapping of the EcoRI fragments of the giant linear plasmid SCP1. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2796–2799. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2796-2799.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan M J. Novobiocin and coumermycin A1. In: Hahn F E, editor. Antibiotics. V, part 1. Mechanism of action of antibacterial agents. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1979. pp. 214–234. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scannell J, Kong Y L. Biosynthesis of coumermycin A1: incorporation of l-proline into the pyrrole groups. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1970;1969:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider A, Stachelhaus T, Marahiel M A. Targeted alteration of the substrate specificity of peptide synthetase by rational module swapping. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;257:308–318. doi: 10.1007/s004380050652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steffensky M, Li S-M, Heide L. Cloning, overexpression, and purification of novobiocic acid synthetase from Streptomyces spheroides NCIMB 11891. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21754–21760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steffensky M, Mühlenweg A, Wang Z-X, Li S-M, Heide L. Identification of the novobiocin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces spheroides NCIB 11891. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1214–1222. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.5.1214-1222.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Symmank H, Saenger W, Bernhard F. Analysis of engineered multifunctional peptide synthetases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21581–21588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tercero J A, Lacalle R A, Jimenez A. The pur8 gene from the pur cluster of Streptomyces alboniger encodes a highly hydrophobic polypeptide which confers resistance to puromycin. Eur J Biochem. 1993;218:963–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thiara A S, Cundliffe E. Expression and analysis of two gyrB genes from the novobiocin producer, Streptomyces sphaeroides. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:495–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsai F T F, Singh O M P, Skarzynski T, Wonacott A J, Weston S, Tucker A, Pauptit R A, Breeze A L, Poyser J P, O'Brien R, Ladbury J E, Wigley D B. The high-resolution crystal structure of a 24-kDa gyrase B fragment from E. coli complexed with one of the most potent coumarin inhibitors, clorobiocin. Proteins. 1997;28:41–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Wageningen A M, Kirkpatrick P N, Williams D H, Harris B R, Kershaw J K, Lennard N J, Jones M, Jones S J M, Solenberg P J. Sequencing and analysis of genes involved in the biosynthesis of a vancomycin group antibiotic. Chem Biol. 1998;5:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walsh T J, Standiford H C, Reboli A C, John J F, Mulligan M E, Ribner B S, Montgomerie J Z, Goetz M B, Mayhall C G, Rimland D, Stevens D A, Hansen S L, Gerard G C, Ragual R J. Randomized double-blinded trial of rifampin with either novobiocin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization: prevention of antimicrobial resistance and effect of host factors on outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1334–1342. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wigley D B, Davies G J, Dodson E J, Maxwell A, Dodson G. Crystal structure of an N-terminal fragment of the DNA gyrase B protein. Nature. 1991;351:624–629. doi: 10.1038/351624a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]