Abstract

Activation and cleavage of carbon–carbon (C–C) bonds is a fundamental transformation in organic chemistry while inert C–C bonds cleavage remains a long-standing challenge. Retro-Diels-Alder (retro-DA) reaction is a well-known and important tool for C–C bonds cleavage but less been explored in methodology by contrast to other strategies. Herein, we report a selective C(alkyl)–C(vinyl) bond cleavage strategy realized through the transient directing group mediated retro-Diels-Alder reaction of a six-membered palladacycle, which is obtained from an in situ generated hydrazone and palladium hydride species. This unprecedented strategy exhibits good tolerances and thus offers new opportunities for late-stage modifications of complex molecules. DFT calculations revealed that an intriguing retro-Pd(IV)-Diels-Alder process is possibly involved in the catalytic cycle, thus bridging both Retro-Diels-Alder reaction and C–C bond cleavage. We anticipate that this strategy should prove instrumental for potential applications to achieve the modification of functional organic skeletons in synthetic chemistry and other fields involving in molecular editing.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Catalysis

Inert C–C bond cleavage remains a challenge in organic chemistry. Herein, the authors report a retro-Diels-Alder process via palladium catalysis to achieve selective C(alkyl)–C(vinyl) bond cleavage.

Introduction

Carbon-carbon (C–C) bonds cleavage is a fundamental and valuable transformation in organic and material sciences for rapid construction and modification of functional organic skeletons1–3. However, compared with the significant progress in C–C bonds formations, extensive efforts in this field have always been hampered by the inherent stability of C–C linkages. Up to date, several metal-mediated strategies, such as oxidative addition4–10, β-carbon elimination11–14, retro-allylation15 and decarboxylation16, have rendered the cleavage of strained and polar C–C bonds feasible. Nevertheless, novel strategies for selective cleavage of inert (unstrained and nonpolar) C-C bonds are still in great demand in both academia and industry17–22.

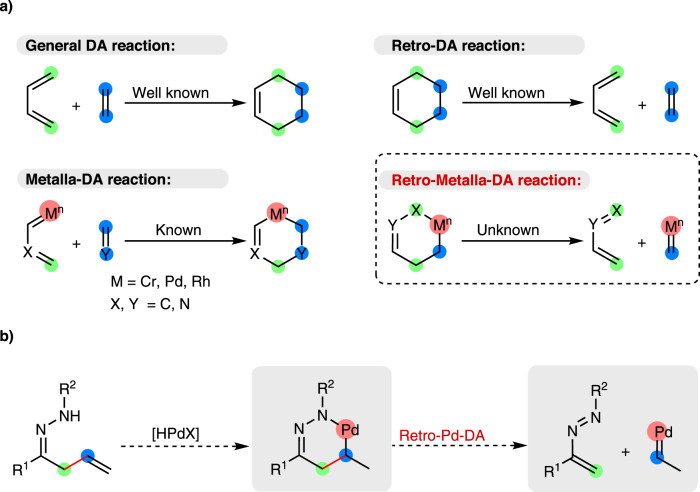

Retro-Diels-Alder (retro-DA) reaction is a well-known and important tool for C–C bonds cleavage23–25, which usually breaks two δ bonds and forms three π bonds simultaneously. Up to now, retro-DA reaction has been used as the key reaction in the synthesis of compounds difficult to obtain by other methods, including polymers, macromolecules, complex natural products and bioactive molecules26,27. Notwithstanding, the capacity of retro-DA reaction has not yet been as fully reached as that of Diels-Alder reaction. The pioneering research of the metalla-Diels-Alder reaction was reported by Wulff in 1989 with a chromadiene as the 4π partner, whereas a terminal carbon in the diene was replaced by chromium (Fig. 1a)28,29. Afterwards, Trost30 and Reißig31 reported the elegant pallada-DA and rhoda-DA reactions. According to the principle of microscopic reversibility, retro-metalla-DA reaction should be applicable as a novel strategy to cleave C–C bonds in theory;32 the formal similarity between the six-membered metallacycles and the six-membered cyclic transition state in retro-DA reactions enhances the feasibility of this method. Furthermore, the universality of cyclometallation makes this strategy a potential complementary and alternative solution to C–C bonds cleavage. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no report of C–C bond cleavage based on retro-metalla-DA reactions. The main challenge lies in the transformation between carbon–metal (C–M) bonds and C–C bonds: (1) formation of six-membered metallacycle is thought to be thermodynamically less favored than its five-membered counterparts33; (2) several side reactions on the six-membered metallacycles, such as reductive elimination34 and β-hydrogen elimination35, are more facile than the retro-metalla-DA reaction; (3) the harsh conditions that are generally required to drive the retro-DA reactions might lead to the side reactions more prominently25. To this end, it is attractive but challenging to address the gap in retro-metalla-DA reactions.

Fig. 1. C-C bond cleavage involving retro-DA reaction.

a Retro-Metalla-Diels-Alder (DA) reaction for C–C bonds cleavage. b Retro-Pallada-DA reaction for C(alkyl)-C(vinyl) bonds cleavage.

Owing to the increasingly extensive and insightful investigations into organopalladium over the last few decades36,37, we envision that a significant breakthrough might be made in the field of C–C bonds cleavage through the rational design of palladacycles38. As shown in Fig. 1b, a six-membered hydrazone-based palladacycle was designed as an ideal substrate for the following reasons: (1) hydrazine-based ketimine has been used for generating palladacycles39; (2) azoalkene has been used as a diene in DA reactions40; (3) it is convenient to directly observe the cleavage selectivity of different types of C–C bonds. According to this hypothesis, the cleavage would selectively occur at C(alkyl)-C(vinyl) bond via a retro-pallada-DA reaction, even in the presence of more active bonds such as polar C(imino)-C(alkyl) and various C–H bonds.

Here, we show a selective C(alkyl)–C(vinyl) bond cleavage strategy through the retro-metalla-Diels-Alder reaction of a six-membered hydrazone-based palladacycle, in situ generated from ketone, hydrazide and palladium catalyst.

Results and discussion

Initially, hydropalladation of α-allyl ketimine (1 A) was utilized to generate the hypothetic six-membered palladacycle and then perform the transformation (Table 1). Different hydrazones were screened in the presence of palladium catalysts and acid additives. After many attempts, the desired C–C bond cleavage was indeed observed in the presence of Pd(PPh3)4 and HBr in toluene (Table 1, entries 1–4). It was found that the N-Ac and N-tBu hydrazones showed better reactivity than N-Ts and N-Bz hydrazones, giving acetophenone 2a directly with 15 and 16% yields, although predictable byproducts 3a and 4a were also detected. These preliminary results verified that our strategy was feasible in certain cases.

Table 1.

Optimization of Retro-Pallada-DA reactiona

| Entry | R | [Pd] | Additive | Solvent | Yield (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 3a | 4a | |||||

| 1 | -Ts | Pd(PPh3)4 | HBr | Tol | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 | -Ac | Pd(PPh3)4 | HBr | Tol | 16 | 19 | 20 |

| 3 | -tBu | Pd(PPh3)4 | HBr | Tol | 15 | 11 | 9 |

| 4 | -Bz | Pd(PPh3)4 | HBr | Tol | 11 | 15 | 16 |

| 5 | -Ac | PdBr2 | — | Tol/iPrOH | 23 | 12 | 8 |

| 6 | -Ac | PdBr2 | PPh3 | Tol/iPrOH | 20 | 0 | 4 |

| 7 | -Ac | PdBr2 | XantPhos | Tol/iPrOH | 18 | 5 | 3 |

| 8 | -Ac | PdBr2 | CO | Tol/iPrOH | 35 | 9 | 2 |

| 9 | -Ac | PdBr2 | CO | DCE/iPrOH | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| 10b | -Ac | PdBr2 | CO | DCE/iPrOH | <5 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | -Ac | PdBr2 | CO/O2 | DCE/iPrOH | 83 | 0 | 0 |

| 12c | -Ac | PdBr2 | CO/O2 | DCE/iPrOH | 86(82) | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | -Ac | — | CO/O2 | DCE/iPrOH | 0 | 0 | 0 |

a Optimization studies; reactions were performed with 0.2 mmol substrates (hydrazone or ketone) in 2.0 mL of solvent for 24 h; GC-FID yield was given. b The reaction was operated in a glovebox in the absence of oxygen. c 1-Phenylbut−3-en-1-one 1a and acetohydrazide were used as the substrates; isolated yield in parenthesis. Ts p-toluenesulfonyl, Ac acetyl, Bz benzoyl.

Therefore, N-Ac hydrazone was chosen as the standard substrate for improving the reaction efficiency. Further studies suggested that the palladium hydride in situ generated from PdBr2/2-propanol displayed higher efficiency (Table 1, entry 5–9). Probably because of the promoting effects of CO in the formation of palladium hydride catalyst41–43, an important improvement was observed in the presence of CO, affording acetophenone 2a with up to a 61% yield in DCE (Table 1, entry 9). Furthermore, we found that the traces of oxygen played an important role in the reaction (Table 1, entry 10 vs. 11). Through an extensive screen of the conditions, the yield of 2a was greatly improved from 61 to 83% in the presence of 1 atm O2 (Table 1, entry 11). Considering that ketone is more common than hydrazone in organic materials, as well as the broad utility of hydrazine as a traceless directing group in the transformation of ketones, we tried the one-pot procedure by using 1-phenylbut-3-en-1-one 1a and acetohydrazide as the substrates. To our delight, an 82% isolated yield of acetophenone 2a was obtained in this case (Table 1, entry 12). For comparison, the reaction did not occur in the absence of palladium catalyst (Table 1, entry 13).

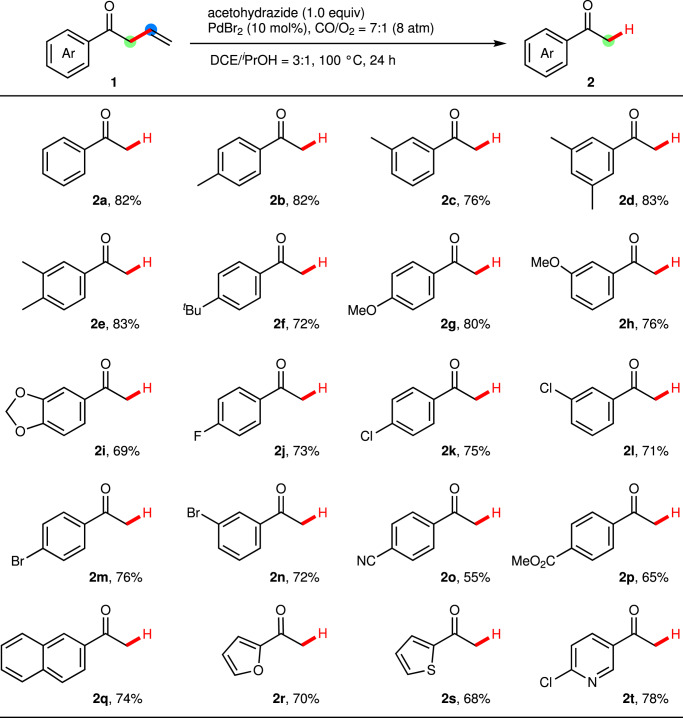

Under optimized reaction conditions, the one-pot procedure was carried out for the structurally diverse screening of substrates. As shown in Fig. 2, this catalytic system is of high functional group tolerance. Aryl allyl ketones possessing para- or meta- electron-donating groups on the aryl ring, such as alkyl, methoxy and [1,3]dioxole, underwent the C–C bond cleavage reaction easily to afford the corresponding aryl methyl ketones (2b-2i) with 69–83% yields. Aryl allyl ketones with halide substituents (F, Cl and Br), which were potentially useful in cross-coupling reactions, were compatible with the optimized conditions to produce the desired products in good to high yields (2j-2n). Notably, strong electron-withdrawing functional groups, such as cyano and ester, afforded the desired acetophenones with satisficing yields (2o and 2p). Besides, this novel catalytic system was applicable for naphthyl and heteroaryl allylic ketones. Representative 2-naphthyl methyl ketone 2q and heteroaryl methyl ketones 2r-2t were obtained in 68–78% yields.

Fig. 2. Scope of substituents on (het)aryl groups (R).

a Conditions: Ketone 1 (0.2 mmol), acetohydrazide (0.2 mmol), PdBr2 (10 mol%), CO/O2 = 7:1 (8 atm), DCE/iPrOH = 3:1 (2.0 mL), 100 °C for 24 h. Isolated yield.

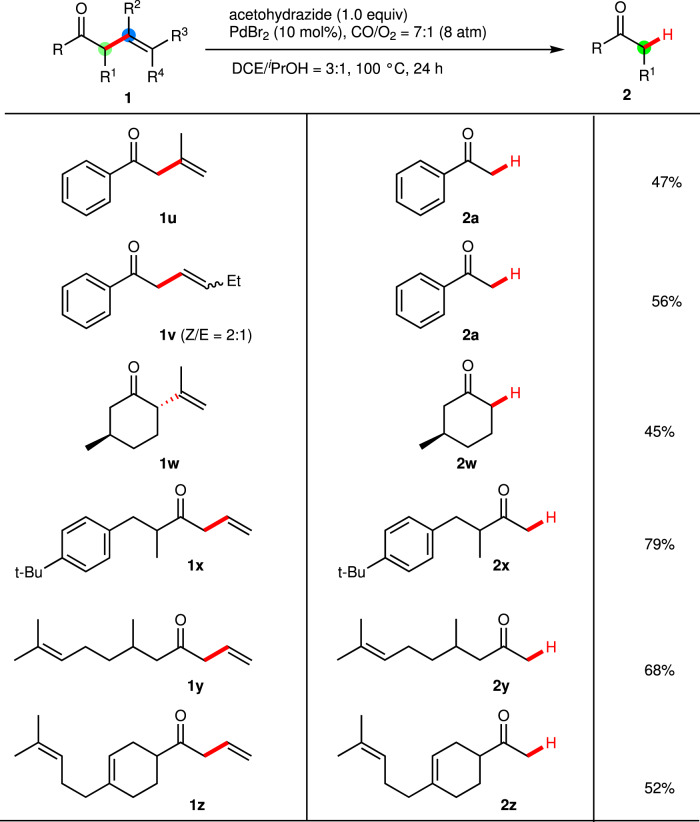

For investigating the universality and regioselectivity of this novel strategy, substrates with substituted vinyl groups were investigated (Fig. 3). Substrate 1u gave 2a in moderate yield, probably because of the steric effect of the methyl group on the C(β). A similar phenomenon was observed for C(γ)-ethyl substituted substrate 1 v, whereas the coordination of the vinyl groups to the metal center was probably suppressed due to the steric effects. Furthermore, alkyl allylic ketones were screened under standard conditions. It is noted that 2w could be obtained from nature product, C(α)- and C(β)-di-substituted (+)-isopulegone 1w, in a 45% yield. The 2x was also obtained in a 79% yield when alkyl allylic ketone 1x was used as the substrate. Furtherly, multiple vinyl substituted substrates with the vinyl group at different positions were tested in the reaction (1 y and 1z). Remarkably, both cyclic C(γ)-vinyl and remote vinyl groups were well retained to afford the desired products 2y-2z in moderate to good yields, demonstrating the chemo- and regioselectivity of the cleavage strategy and potential further application for late-stage synthetic modifications of complex molecules.

Fig. 3. Scope of substituents on allyl groups (R1-R4) and alkyl/alkenyl groups (R).

a Conditions: Ketone 1 (0.2 mmol), acetohydrazide (0.2 mmol), PdBr2 (10 mol%), CO/O2 = 7:1 (8 atm), DCE/iPrOH = 3:1 (2.0 mL), 100 °C for 24 h. Isolated yield.

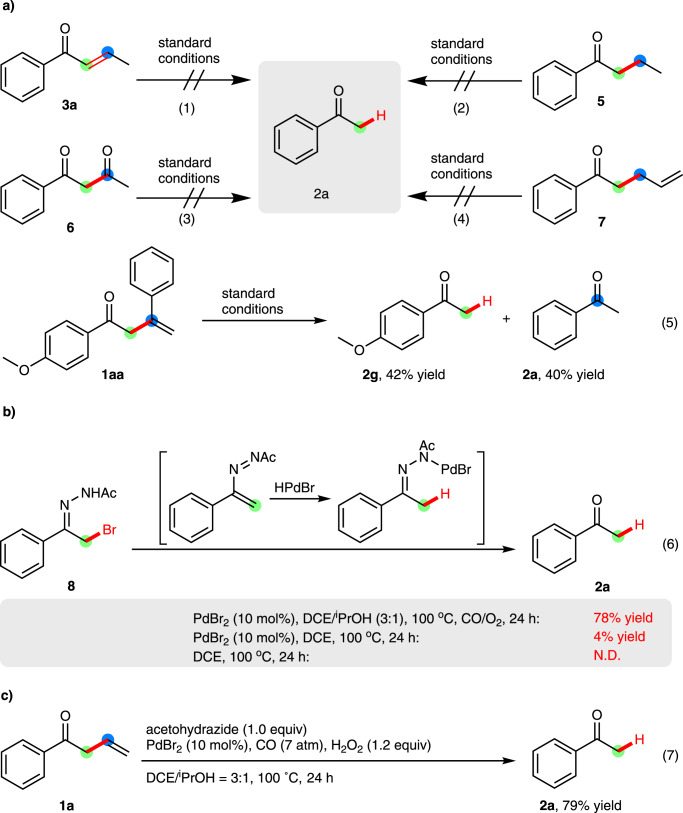

To gain insights into this novel C–C bond cleavage process, a series of detailed control experimental studies were performed under the standard conditions (Fig. 4). The migration (3a and 7), hydrogenation (5) or oxygenation (6) of the vinyl group resulted in the failure of obtaining desired product 2a, implying a remarkable dependency of β,γ-vinyl ketone conformation and highly specific selectivity of the reaction site. These results also excluded the potential participation of 3a, 5 or 6 as the key intermediates. Furthermore, a piece of important experimental evidence was observed when 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-3-phenylbut-3-en-1-one 1aa was used as the substrate under the standard conditions, wherein the desired ketone 2 g was obtained in 42% yield accompanied with ketone 2a in 40% yield (Fig. 4, equation 5). Afterwards, N’-(2-bromo-1-phenylethylidene) acetohydrazone 8, a precursor of ‘diene’ azoalkene44–48, gave 2a in a 78% yield under standard conditions (Fig. 4, equation 6), demonstrating the possibility that azoalkene was involved as an intermediate in the reaction. In addition, considering the critical role of PdBr2 and 2-propanol in this transformation, we assumed that the final ketone 2a might be produced through a process of 1,4-addition of palladium-hydride into azoalkene species followed by hydrolysis (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 4. Control Experiments.

a Investigation of potential pathway and key intermediates by using substituted substrates. b Investigation of potential intermediates by using azoalkene precursor. c Investigation of potential role of O2 by using H2O2.

Based on the above results, we proposed that this C(alkyl)–C(vinyl) bond cleavage proceeded through the following key steps involving a six-membered palladacycle (Fig. 5a, path I): (1) insertion of palladium-hydride species (HPdBr) to 1 A generate an alkyl-palladium intermediate Int-A;49–51 (2) cyclization of the Int-A forms a six-membered palladacycle Int-B; (3) retro-Pd(II)-DA reaction of the palladacycle affords an azo-‘diene’ Int-C and a Pd-carbene; and (4) reductive hydrolysis of Int-C gives the final product 2a. Detailed processes were explored by carrying on DFT calculations (Fig. 5b). The N-tBu-1A, which has similar reactivity as N-Ac-A under the standard conditions, was used as the model substrate to restrain the intramolecular coordination (see Supplementary Information).

Fig. 5. Mechanism investigation.

a Proposed Mechanism (ligands are omitted for clarity). b DFT calculated relative Gibbs free energy profiles for the paths I, II and III by B3LYP-D3(dichloroethane)/{6-311 + +G(d,p), SDD(Pd)} with respective to Im1. c Activation barrier of retro-Pd-DA step. d Activation barrier of the overall path.

For the path I (Fig. 5b, black line), the steps (1) and (2) seem to be reasonable with an overall activation barrier of 27.6 kcal/mol, while the individual retro-Pd(II)-DA step requires a relatively high barrier of 48.6 kcal/mol with respect to I-Im5 (Fig. 5c). However, the transformation from Im1 to I-Im6 requires an overall activation barrier of 76.2 kcal/mol (Fig. 5d, path I), which is highly prohibited in theory. Considering that oxygen played an important role in the reaction (Table 1, entry 10), as well as that the reaction proceeded smoothly to give the desired product 2a in 79% yield when 1.2 equiv. of hydrogen peroxide was used instead of oxygen (Fig. 4, equation 7), we hypothesized that the hydrogen peroxide would be easily formed from O2/ DCE/iPrOH in the presence of palladium catalyst and improve the transformation52,53. Therefore, two competitive mechanistic pathways are proposed as an alternative, wherein the Pd(IV) intermediates might be involved in the reaction54. In this context, oxidation of Pd(II) to Pd(IV) may take place at Int-A or Int-B, namely as Pd(II) cyclization-retro-Pd(IV)-DA (Fig. 5a, path II) and Pd(IV) cyclization-retro-Pd(IV)-DA (Fig. 5a, path III).

For the path II (Fig. 5b, purple line), six-membered Pd(IV)-cycle II-Im9 is formed from Im1 with an overall barrier of 55.7 kcal/mol through the sequential insertion, cyclization and oxidation. Afterwards, the retro-Pd(IV)-DA reaction of II-Im9 proceeds with an activation barrier of 35.7 kcal/mol to give II-Im10 via transition state II-TS4 (Fig. 5c). As a result, the transformation from Im1 to II-Im10 requires a relatively high overall activation energy of 55.7 kcal/mol (Fig. 5d, path II).

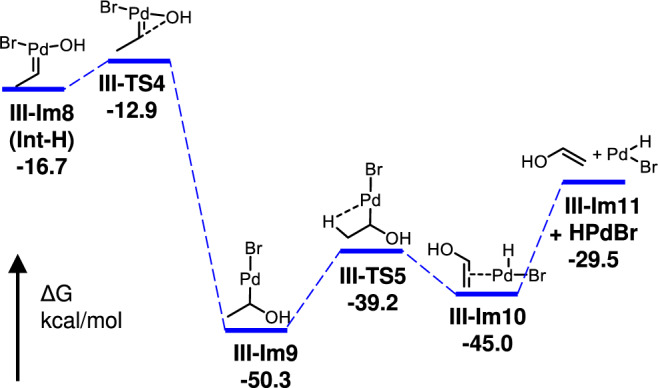

For the path III (Fig. 5b, blue line), six-membered Pd(IV)-cycle III-Im6 is formed from Im1 with an overall activation barrier of 29.3 kcal/mol through sequential insertion of palladium-hydride (I-Im2), binding with H2O2 (III-Im3), releasing of CO (III-Im4) and H2O (III-Im5). Then, the retro-Pd(IV)-DA reaction of III-Im6 occurs via transition state III-TS3 with an activation barrier of 29.6 kcal/mol, which is more energetically favorable than path I and path II (Fig. 5c). As a result, the transformation from Im1 to III-Im7 requires the lowest overall activation barries of three pathways (29.6 vs 55.7 and 76.2 kcal/mol, respectively) (Fig. 5d, path III). Subsequently, the exothermic OH migration of III-Im8 requires lower barriers and provides driving forces to the retro-Pd(IV)-DA step (Fig. 6)55. Notably, the DFT calculations indicated that CO played an important role in the transformation of the active palladium hydride species41–43, which is consistent with the experimental results in this work.

Fig. 6. DFT calculated Gibbs free energy profiles for regeneration HPdBr catalyst from Int-H.

Origin of the free energies is with respect to Im1 in Fig. 5b.

In summary, we have reported an unconventional retro-pallada-Diels-Alder reaction for the first time and realized the palladium catalyzed inert C(alkyl)–C(vinyl) bonds cleavage via this strategy. The key six-membered Pd(IV)-cycle is probably generated from the sequential hydrazide-assisted [PdH] insertion into the C = C double bond and oxidation of the Pd(II) intermediate, which is supported by our experimental and computational investigations. This strategy has achieved highly selective transformation of a series of substituted substrates. Therefore, we anticipate that this unprecedented tactic would offer new opportunities for inert C-C bond cleavage, and therefore potentially applicable to achieve the modification of functional organic skeletons.

Methods

Typical procedure for palladium-catalyzed C(alkyl)-C(vinyl) cleavage

Ketone 1a (0.2 mmol), PdBr2 (10 mol%, 5.3 mg), acetohydrazide 2a (0.2 mmol, 14.8 mg) and 2 mL mixed solvents (DCE/iPrOH = 3/1) was added to a 10 mL glass vial capped with perforated aluminum foil. The vial was transferred into an autoclave, which was carefully evacuated and backfilled with O2 (1 atm) and then filled by CO (7 atm). After being stirred at 100 °C oil bath for 24 h, the autoclave was cooled down to room temperature and then the gas was released slowly. The reaction mixture was quenched with H2O (10 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and then evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to afford the corresponding acetophenone 2a with hexanes/EtOAc (20/1) as the eluent.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21971204, 22171224), the Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi Province (No. 2020TD-022) and Fund of Education Department of Shaanxi Provincial Government (22JP082). Q.Z. thanks the Science, Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen (JCYJ20190807155201669).

Author contributions

Z.G. conceived the original idea and directed the research. L.Y. performed the DFT calculations. Z.G. L.Y. and Q.Z. designed experiments and analyzed the data. Y.Z., Y.G., M.C., Z.R. performed the synthetic experiments. Q.Z., L.Y., and Z.G. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all the authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data relating to the characterization of products, experimental protocols and the computational studies are available within the article and its Supplementary Information.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Qingyang Zhao, Le Yu, Yao-Du Zhang.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-38067-7.

References

- 1.Dong, G. (ed). C-C bond activation. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2014).

- 2.Murakami, MChatani, N. (eds). Cleavage of carbon-carbon single bonds by transition metals. (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim: Germany, 2016).

- 3.Sarpong R, Wang B, Perea MA. Transition metal-mediated C–C single bond cleavage: making the cut in total synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:18898–18919. doi: 10.1002/anie.201915657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Souillart L, Cramer N. Catalytic C–C bond activations via oxidative addition to transition metals. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:9410–9464. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fumagalli G, Stanton S, Bower JF. Recent methodologies that exploit C–C single-bond cleavage of strained ring systems by transition metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:9404–9432. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakao Y. Metal-mediated C–CN bond activation in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2020;121:327–344. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gozin M, Weisman A, Ben-David Y, Milstein D. Activation of a carbon–carbon bond in solution by transition-metal insertion. Nature. 1993;364:699–701. doi: 10.1038/364699a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami M, Amii H, Ito Y. Selective activation of carbon–carbon bonds next to a carbonyl group. Nature. 1994;370:540–541. doi: 10.1038/370540a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia Y, Lu G, Liu P, Dong G. Catalytic activation of carbon–carbon bonds in cyclopentanones. Nature. 2016;539:546–550. doi: 10.1038/nature19849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruffoni A, Hampton C, Simonetti M, Leonori D. Photoexcited nitroarenes for the oxidative cleavage of alkenes. Nature. 2022;610:81–86. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masahiro M, Masaomi M, Shinji A, Takanori M. Construction of carbon frameworks through β-carbon elimination mediated by transition metals. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2006;79:1315–1321. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.79.1315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Reilly ME, Dutta S, Veige AS. β-alkyl elimination: fundamental principles and some applications. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:8105–8145. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald TR, Mills LR, West MS, Rousseaux SAL. Selective carbon–carbon bond cleavage of cyclopropanols. Chem. Rev. 2020;121:3–79. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchese AD, Mirabi B, Johnson CE, Lautens M. Reversible C–C bond formation using palladium catalysis. Nat. Chem. 2022;14:398–406. doi: 10.1038/s41557-022-00898-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nogi K, Yorimitsu H. Carbon–carbon bond cleavage at allylic positions: Retro-allylation and deallylation. Chem. Rev. 2021;121:345–364. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodríguez N, Goossen LJ. Decarboxylative coupling reactions: a modern strategy for C–C-bond formation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:5030–5048. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15093f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang G, et al. Migrative carbofluorination of saturated amides enabled by Pd-based dyotropic rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:14047–14052. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c06578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu X, et al. Cleaving arene rings for acyclic alkenylnitrile synthesis. Nature. 2021;597:64–69. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03801-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y, et al. Deacylative transformations of ketones via aromatization-promoted C-C bond activation. Nature. 2019;567:373–378. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0926-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smaligo AJ, et al. Hydrodealkenylative C(sp3)–C(sp2) bond fragmentation. Science. 2019;364:681–685. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw4212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu B, et al. Cleavage of a C–C σ bond between two phenyl groups under mild conditions during the construction of Zn(II) organic frameworks. Green. Chem. 2016;18:5418–5422. doi: 10.1039/C6GC01686C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu J, Wang J, Dong G. Catalytic activation of unstrained C(aryl)–C(aryl) bonds in 2,2′-biphenols. Nat. Chem. 2019;11:45–51. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0157-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA, Montagnon T, Vassilikogiannakis G. The Diels–Alder reaction in total synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1668–1698. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1668::AID-ANIE1668>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Funel J-A, Abele S. Industrial applications of the Diels–Alder reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:3822–3863. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotha S, Banerjee S. Recent developments in the retro-Diels–Alder reaction. RSC Adv. 2013;3:7642–7666. doi: 10.1039/c3ra22762f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu WC, Wang Z, Chan WTK, Lin Z, Kwong FY. Regioselective synthesis of polycyclic and heptagon-embedded aromatic compounds through a versatile π-extension of aryl halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:7166–7170. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang B-S, et al. Synthesis of C4-aminated indoles via a catellani and retro-Diels–Alder strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:9731–9738. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b05009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu YC, et al. The generation of 2-vinylcyclopentene-1,3-diones via a five-component coupling in the coordination sphere of chromium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:7269–7271. doi: 10.1021/ja00200a062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kagoshima H, Okamura T, Akiyama T. The asymmetric [3+2] cycloaddition reaction of chiral alkenyl fischer carbene complexes with imines: Synthesis of optically pure 2,5-disubstituted-3-pyrrolidinones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7182–7183. doi: 10.1021/ja015866z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trost BM, Hashmi ASK. A cycloaddition approach to cyclopentenes via metalladienes as 4.Pi. Partn. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:2183–2184. doi: 10.1021/ja00084a084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnaubelt J, Marks E, Reißig H-U. [4 + 1] cycloadditions of the rhodium di(methoxycarbonyl) carbenoid to 2-siloxy-1,3-dienes. Chem. Ber. 1996;129:73–75. doi: 10.1002/cber.19961290115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houk KN, Liu F, Yang Z, Seeman JI. Evolution of the Diels–Alder reaction mechanism since the 1930s: Woodward, Houk with Woodward, and the influence of computational chemistry on understanding cycloadditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:12660–12681. doi: 10.1002/anie.202001654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia G, et al. Reversing conventional site-selectivity in C(sp3)–H bond activation. Nat. Chem. 2019;11:571–577. doi: 10.1038/s41557-019-0245-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsang WCP, Zheng N, Buchwald SL. Combined C−H functionalization/C−N bond formation route to carbazoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14560–14561. doi: 10.1021/ja055353i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sumida Y, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Palladium-catalyzed preparation of silyl enolates from α,β-unsaturated ketones or cyclopropyl ketones with hydrosilanes. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:7986–7989. doi: 10.1021/jo901513v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuji J, editor. Palladium reagents and catalysts. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartwig, J. F. Organotransition metal chemistry: From bonding to catalysis (University Science Books, 2010).

- 38.Dupont J, Consorti CS, Spencer J. The potential of palladacycles: more than just precatalysts. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2527–2572. doi: 10.1021/cr030681r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang Z, Wang C, Dong G. A hydrazone-based exo-directing-group strategy for β C-H oxidation of aliphatic amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:5299–5303. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopes SMM, Cardoso AL, Lemos A, Pinho e Melo TMVD. Recent advances in the chemistry of conjugated nitrosoalkenes and azoalkenes. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:11324–11352. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao Y-H, et al. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric Markovnikov hydroxycarbonylation and hydroalkoxycarbonylation of vinyl arenes: synthesis of 2-arylpropanoic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:23117–23122. doi: 10.1002/anie.202107856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang H-Y, et al. Palladium-catalyzed Markovnikov Hydroaminocarbonylation of 1,1-disubstituted and 1,1,2-trisubstituted alkenes for formation of amides with quaternary carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:7298–7305. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c03454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao Y-H, et al. Asymmetric Markovnikov hydroaminocarbonylation of alkenes enabled by palladium-monodentate phosphoramidite catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:85–91. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c11249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Attanasi OA, Filippone P. Working twenty years on conjugated azo-alkenes (and environs) to find new entries in organic synthesis. Synlett. 1997;1997:1128–1140. doi: 10.1055/s-1997-973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao H-W, et al. Construction of 2,3,4,7-Tetrahydro-1,2,4,5-oxatriazepines via [4+3] cycloadditions of α-Halogeno hydrazones with nitrones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016;358:1826–1832. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201600093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pedrón M, Delso I, Tejero T, Merino P. Concerted albeit not pericyclic cycloadditions: understanding the mechanism of the (4+3) cycloaddition between nitrones and 1,2-diaza-1,3-dienes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019;2019:391–400. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201800663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei L, et al. Catalytic asymmetric inverse electron demand Diels–Alder reaction of fulvenes with azoalkenes. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:2506–2509. doi: 10.1039/C7CC09896K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emamian S, Soleymani M, Moosavi SS. Copper(I)-catalyzed asymmetric aza-Diels–Alder reactions of azoalkenes toward fulvenes: a molecular electron density theory study. New J. Chem. 2019;43:4765–4776. doi: 10.1039/C9NJ00269C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peterson KP, Larock RC. Palladium-catalyzed oxidation of primary and secondary allylic and benzylic alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3185–3189. doi: 10.1021/jo971268k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mueller JA, Goller CP, Sigman MS. Elucidating the significance of β-hydride elimination and the dynamic role of acid/base chemistry in a palladium-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9724–9734. doi: 10.1021/ja047794s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Konnick MM, Gandhi BA, Guzei IA, Stahl SS. Reaction of molecular oxygen with a Pd(II)- hydride to produce a Pd(II)–hydroperoxide: acid catalysis and implications for Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:2904–2907. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bortolo R, Bianchi D, D’Aloisio R, Querci C, Ricci M. Production of hydrogen peroxide from oxygen and alcohols, catalyzed by palladium complexes. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2000;153:25–29. doi: 10.1016/S1381-1169(99)00350-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stahl SS. Palladium oxidase catalysis: selective oxidation of organic chemicals by direct dioxygen-coupled turnover. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3400–3420. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sehnal P, Taylor RJK, Fairlamb IJS. Emergence of palladium(IV) chemistry in synthesis and catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:824–889. doi: 10.1021/cr9003242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia Y, et al. Palladium-catalyzed carbene migratory insertion using conjugated ene–yne–ketones as carbene precursors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:13502–13511. doi: 10.1021/ja4058844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data relating to the characterization of products, experimental protocols and the computational studies are available within the article and its Supplementary Information.