Abstract

Background

Physicians treating similar patients in similar care-delivery contexts vary in the intensity of life-extending care provided to their patients at the end-of-life. Physician psychological propensities are an important potential determinant of this variability, but the pertinent literature has yet to be synthesized.

Objective

Conduct a review of qualitative studies to explicate whether and how psychological propensities could result in some physicians providing more intensive treatment than others.

Methods

Systematic searches were conducted in five major electronic databases—MEDLINE ALL (Ovid), Embase (Elsevier), CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycINFO (Ovid), and Cochrane CENTRAL (Wiley)—to identify eligible studies (earliest available date to August 2021). Eligibility criteria included examination of a physician psychological factor as relating to end-of-life care intensity in advanced life-limiting illness. Findings from individual studies were pooled and synthesized using thematic analysis, which identified common, prevalent themes across findings.

Results

The search identified 5623 references, of which 28 were included in the final synthesis. Seven psychological propensities were identified as influencing physician judgments regarding whether and when to withhold or de-escalate life-extending treatments resulting in higher treatment intensity: (1) professional identity as someone who extends lifespan, (2) mortality aversion, (3) communication avoidance, (4) conflict avoidance, (5) personal values favoring life extension, (6) decisional avoidance, and (7) over-optimism.

Conclusions

Psychological propensities could influence physician judgments regarding whether and when to de-escalate life-extending treatments. Future work should examine how individual and environmental factors combine to create such propensities, and how addressing these propensities could reduce physician-attributed variation in end-of-life care intensity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-08011-4.

KEY WORDS: physician variation, practice variation, physician psychology, physician behavior, end-of-life care, care intensity, low-value care, futile care, aggressive care, decision-making

INTRODUCTION

Physicians treating similar patients in similar care-delivery contexts vary in the intensity of life-prolonging and life-extending care provided to their patients at the end-of-life.1–5 Notably, the influence of the treating physician on end-of-life care intensity seems to be as high or higher than patient factors, disease characteristics, or regional norms.6–10 In fact, it has been estimated that a striking 35% of end-of-life care spending is associated with physician beliefs and treatment preferences that are not associated with evidence-based practice.1 Such physician-specific variation raises the question of, why, given similar clinical scenarios, some physicians provide more intensive care than others. This is a particularly important question considering that higher end-of-life care intensity has been associated with an array of poor outcomes,11–13 such as lower patient quality of life, higher caregiver post-traumatic stress symptoms, and higher provider burnout.14–16.

One likely factor associated with physician variation in end-of-life care intensity is differences in the psychological propensities of individual physicians.2,4,17–19 Physician psychological propensities have previously been demonstrated to be consequential for other types of practice patterns. For example, physicians who are more risk-averse use more imaging among emergency department patients,20 and physicians who are more concerned about malpractice engage in more aggressive diagnostic testing in office-based practice.21 Similarly, physician psychological propensities may be consequential for practice patterns around end-of-life care intensity.

To date, numerous qualitative studies have examined physician psychological propensities as they relate to end-of-life care intensity.22–24 However, there have been no efforts to synthesize this literature to explicate whether and how differences in physician psychology may translate to some physicians providing more intensive end-of-life treatment than others. To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies that examined physician psychological propensities associated with end-of-life care intensity.

Our conceptual lens centered on the notion that making end-of-life care intensity decisions involves certain psychological tasks such as facing the unpleasant prospect of patient’s death, suffering, medical uncertainty, being the bearer of bad news, strong patient and family emotions, pressure from patients and families to “do more,” and pressure to conform to a biomedical norm of offering life-extending care.25–29 How physicians experience and manage these psychological tasks could potentially lead to systematic variation in the level of treatment intensity deemed appropriate and provided by individual physicians.22,30,31 The present review therefore aimed to identify the psychological propensities around how physicians navigate these psychological tasks, resulting in a proclivity for greater or lesser end-of-life care intensity. Such psychological propensities are likely a product of both individual (e.g., personality traits) and environmental factors (e.g., professional socialization, culture of medicine). Results from the present review would therefore have actionable implications, informing efforts to improve care through physician-focused interventions (e.g., self-awareness-based interventions) and structural changes (e.g., changes to medical education).32–34

METHODS

Literature Search

Five databases were searched—MEDLINE ALL via Ovid, Embase via Elsevier’s Embase.com, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Cochrane CENTRAL) via Wiley’s Cochrane Library, PsycINFO via Ovid, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EBSCO—on August 27, 2021. The search strategy was developed in MEDLINE by a Research Informationist (KG) in collaboration with the research team using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords for three concepts: Psychological Factors of Physician-Level Providers, Treatment Intensity, and End-of-Life. Concepts were combined with the Boolean AND operator. A second Research Informationist performed a Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) and edits were implemented. The search strategy was then translated to the other databases using available controlled vocabulary (see Supplementary Information). Results were entered in RIS file format in Covidence, a Web-based software platform for systematic review development that includes the deduplication of uploaded records. This review was preregistered with PROSPERO (CRD42021279229).

Review of References and Eligibility Criteria

References underwent an initial title/abstract screening and a subsequent full-text screening, with each reference reviewed by two undergraduate coders. Discrepancies or ambiguities in coding were resolved via discussion with the first author or the research team. Our primary inclusion criterion was whether a reference featured examination of the association between a psychological propensity and end-of-life care intensity. Psychological propensity was defined as any physician cognitive, affective, or behavioral variable or process cited as being consequential for physicians’ decisions regarding end-of-life care intensity. End-of-life care intensity was defined using standard metrics:11–13,35 (i) hospitalizations (acute hospital; intensive care unit; emergency department); (ii) life-sustaining interventions (e.g., resuscitation, intubation, mechanical ventilation, artificial feeding, dialysis) or life-prolonging treatments (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, transfusions); and (iii) hospice care. We define advanced, life-limiting illness as an incurable illness that is known to shorten lifespan (e.g., advanced cancer, advanced heart failure, advanced renal disease, advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).36,37 Only references in English were included due to language limitations of the study team. Additional eligibility criteria included the sample being composed of at least majority physicians (i.e., >50%).

Data Abstraction, Meta-synthesis, and Quality Appraisal

The data synthesis approach involved extracting relevant findings from each reference into NVivo (qualitative data analysis software) and conducting a thematic analysis.38 Relevant findings were defined as information from “Results” or “Findings” sections of each reference that suggest that a physician psychological propensity was or was not related to end-of-life care intensity. Data extraction for each reference was conducted by a primary coder and reviewed by a second coder for accuracy. The thematic analysis was carried out by a four-member coding team (LG, AK, EP, LP). In the first phase, each of the four coders independently read the extracted data and created codes capturing different psychological propensities. During consensus meetings, these codes were then compared and integrated to arrive at a final set of codes. Each coding team member then independently coded the extracted content using the final codes. During subsequent research team meetings, codes with low interrater reliability were discussed and refined, and codes were categorized into broader analytic themes pertinent to study questions. Finally, to assess quality of the included studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist was used,39 with each study rated by two coders. The CASP tool evaluates references on features such as study methodology, recruitment strategy, ethical considerations, and data analysis. Given the lack of consensus in the literature on whether quality appraisal should be grounds for excluding references in qualitative systematic reviews, references were not excluded based on their quality appraisal.40

RESULTS

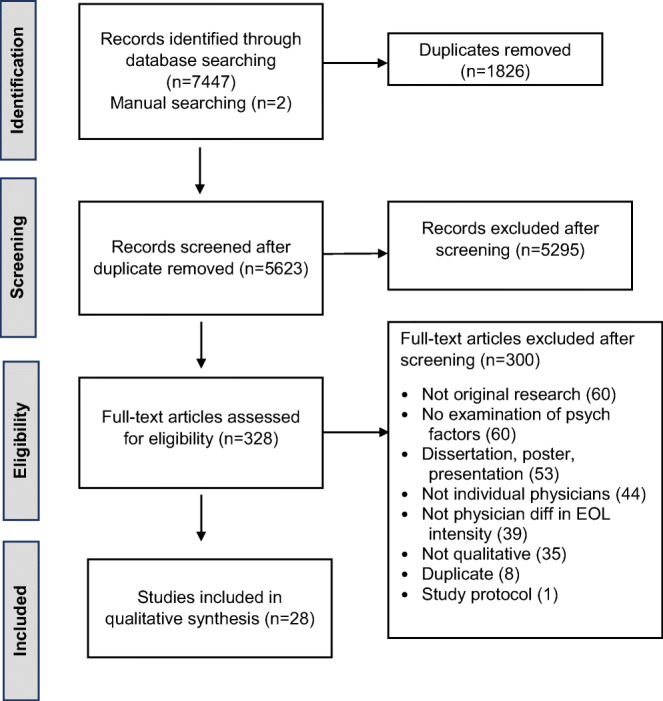

The literature search identified 5623 non-duplicate references, 328 of which were selected for full text review; 28 met the eligibility criteria (PRISMA flowsheet, Fig. 1), including 9 studies on cancer, 2 on kidney failure, 2 on brain injury/cognitive impairment, and 15 on multiple types of serious illnesses. Fourteen studies pertained to life-sustaining treatment decisions (e.g., resuscitation), and 8 pertained to cancer chemotherapy decisions. Most of the included studies were conducted in Western countries (23 out of 28), with 10 conducted in the USA (study characteristics, Table 1). Median sample size was 23 (range, 7–96), and most studies involved individual interviews with participants. Most studies demonstrated good study quality on the CASP quality appraisal tool (see Supplementary information, Table A).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Study | Country | Sample size | Data collection | Clinician specialty | Focal treatment decision | Illness/decisional context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aita 2007 | Japan | 30 | Interviews | Mixed | Artificial nutrition and hydration | Severely cognitively impaired older adults |

| Asai 1997 | Japan | 7 | Focus group | Internists | Life-sustaining treatments | Serious illness, unspecified |

| Bluhm 2016 | USA | 17 | Interviews | Oncologists | Chemotherapy | Advanced cancer |

| Bluhm 2017 | USA | 17 | Interviews | Oncologists | Chemotherapy | Advanced cancer |

| Broom 2013 | Australia | 20 | Interviews | Primarily oncologists | Transitioning out of active treatment and to palliation | Serious illness, unspecified |

| Buiting 2011 | Netherlands | 27 | Interviews | Oncology clinicians | Chemotherapy | Advanced cancer |

| Carmel 1996 | Israel | 25 | Interviews | Mixed | Life-sustaining treatments | Serious illness, unspecified |

| Catlin 1999 | USA | 54 | Interviews | Primarily neonatologists | Resuscitation | Extremely low-birth-weight preterm infants |

| Dupont-Thibodeau 2017 | Canada | 80 | Interviews | Pediatric clinicians | Resuscitation | Neonates and mixed critically ill patients |

| Dzeng 2018 | USA | 42 | Interviews | Internal medicine | Resuscitation | Serious illness, unspecified |

| Haliko 2018 | USA | 73 | Interviews (regarding clinical simulation) | Emergency medicine, hospitalist, and intensivist physicians | Intubation | Critically and terminally ill elder presenting to emergency department |

| Jox 2012 | Germany | 29 | Interviews | Intensive and palliative care clinicians | Life-sustaining treatments | Serious illness, unspecified |

| Kryworuchko 2016 | Canada | 30 | Interviews | Mixed | Life-sustaining treatments | Serious illness within acute patient care |

| Laryionava 2018 | Germany | 29 | Interviews | Oncology clinicians | Chemotherapy | Advanced cancer |

| Lotz 2016 | Germany & Switzerland | 17 | Focus groups | Pediatric clinicians | Life-sustaining treatment (within case scenarios) | Seriously ill children |

| Marmo 2014 | USA | 9 | Interviews | Oncologists | Hospice | Advanced cancer |

| Mobasher 2013 | Iran | 8 | Interviews | Oncologists | Cancer-directed treatment | Advanced cancer |

| Nordenskjold Syrous 2020 | Sweden | 19 | Interviews | Intensivists | Life-sustaining treatments | Serious illness within intensive care unit |

| Nordenskjold Syrous 2020 | Sweden | 19 | Interviews | Intensivists | Life-sustaining treatments | Serious illness within intensive care unit |

| Odejide 2014 | USA | 20 | Focus groups | Hematologic oncologists | Transitioning from disease-directed care to end-of-life care | Advanced hematologic cancer |

| Ozeki-Hayashi 2019 | Japan | 21 | Interviews | Breast surgeons | Chemotherapy | Advanced breast cancer |

| Robertsen 2019 | Norway | 18 | Interviews | Neurocritical care physicians | Life-sustaining treatments | Devastating brain injury within neurocritical care unit |

| Schildmann 2013 | England | 12 | Interviews | Medical oncologists | Cancer-directed treatments | Advanced cancer |

| Sercu 2015 | Belgium | 52 | Interviews | General practitioners | End-of-life care unspecified | End-of-life home care for advanced serious illness |

| St. Clair Russell 2021 | USA | 54 | Interviews and focus groups | Nephrology clinicians | Dialysis | Kidney failure |

| Wachterman 2019 | USA | 20 | Interviews | Nephrologists | Dialysis | Advanced kidney disease among older adults |

| Willmott 2016 | Australia | 96 | Interviews | Mixed | “Futile treatments” | End-of-life, unspecified |

| Wilson 2013 | USA | 27 | Interviews | Critical care clinicians | Life support | Serious illness within intensive care unit |

Key Themes

Thematic analysis of the extracted study results yielded 7 themes (Table 2; illustrative quotes, Table 3).

Table 2.

Physician Psychological Propensities Identified in Thematic Analysis as Driving Greater End-of-Life Treatment Intensity

|

Professional identity as “fixer”: Sense of one’s role and job as extending life or curing disease and providing treatments to that end. Associated with potential feelings of personal failure, role failure, disappointment, powerlessness, a sense of “battle lost,” and “giving up,” when faced with decisions to de-escalate or withholding life-extending treatments | |

|

Mortality aversion: Experienced distress, unpleasantness, or negative arousal associated with witnessing human suffering, illness progression, and mortality (i.e., extend to which it is unsettling or upsetting), potentially exacerbated by greater identification or perceived connection with patient or perceived unfairness of illness | |

|

Communication avoidance: Having less interest, comfort, ability and efficacy with having end-of-life care discussions with patients and families and in supporting them to be prepared and ready to make difficult treatment decisions | |

|

Conflict avoidance: Proclivity to please patient/family; experienced aversion to disappointing or upsetting the patient/family, avoid conflict with them, and avoid dissatisfaction with doctor and doctor shopping. Inclination to concede to patient/family treatment requests even when the physicians’ own judgment for treatments is different (e.g., family requests potentially futile treatments) | |

|

Personal values regarding life extension Personal values and beliefs (religious or secular) regarding life extension and end-of-life care that are projected on to patients during treatment decision-making or communication | |

|

Decisional avoidance Tendency to deal with decisional uncertainty and associated cognitive conflict by avoiding or deferring a treatment decision (e.g., defaulting to continuing life-extending treatments; deferring the decision to discontinue treatments) | |

|

Over-optimism The exhibited proclivity when reasoning about treatment choices that perhaps the odds could be beat and a positive outcome could be attained |

For quotes illustrating each theme, see Table 3

Table 3.

Illustrative Quotes from Included Studies

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| Professional identity as “fixer” |

Some doctors really do believe that they did medicine to never give up on a patient…23 The ‘dogged pursuit of active treatment’, as one specialist described it, was talked about as underpinned by a subjective perception of the medical role as ‘disease beater’ rather than bearer of ‘bad news’. – Study authors43 Sometimes there is this urge like you have to offer something [be]cause you’re called to be the oncologist.22 We don’t want to tell somebody we can’t do anything for them…you feel bad when you don’t have anything to offer someone.22 I’m a nephrologist ‘cause I can always fix it...I want to keep them alive and not have them die from the problem that I’m in charge of. So I have that machine, and I can do that, so it’s very hard not to.50 |

| Mortality aversion |

To let a person die from hunger is psychologically difficult for me, feeding quiets a physician's conscience. When I give artificial feeding to a terminal patient, it makes me feel that I didn't abandon him and just let him die56 [Not initiating dialysis] is very difficult because... you’re watching people die, which is inherently stressful, and you do know you could reverse [it] for a few months...You feel compelled to offer it.50 …more ‘emotive’ doctors ‘tend to push for more futile treatment’ because they have a harder time accepting death. – Study authors23 …somebody comes in with young kids, that’s not just hard for them handle, that’s hard for us to handle.55 Especially if these patients show maybe some parallels to one’s own life, or are maybe in a similar life situation, have small children, then it is very depressing and stressful to make such decisions.24 …it gets harder and harder with each passing month to make that objective decision, cause we’ve grown a little close, and so it becomes harder and harder, I always want to do something.49 |

| Communication avoidance |

It’s a hell of a lot easier conversation to say, ‘Alright, let’s do your next round of chemo. I’ll see you in 3 weeks,’ rather than have a conversation to say I don’t think we should do more chemo.22 … Probably we tend to avoid the really difficult [end-of-life] issues, and sort of hope that the palliative care physician will deal with those things. Because I mean, I personally find those end-of-life kind of issues very difficult to deal with, and to broach with a patient.43 …it’s a bit uncomfortable approaching that [end of life care] particularly in the presence of the patient, hence the hesitation.64 I think even just saying, ‘well, you may become nauseated or you may get increasing swelling or things like that,’ is a very different than saying, ‘and eventually you will die from your kidney disease.’ Just saying those words is a lot harder.63 ... it's easier to continue rather than say to the patient let's stop. That's a harder thing to say and it takes a longer consultation in a busy clinic. It's easiest to continue for the time being.23 |

| Conflict avoidance |

Intellectually, I know this probably isn’t what I should be doing, but I don’t want to disappoint…disappointing people on a regular basis, wears on ya...and then you get the ultimate disappointment with that discussion we’ve been talking about where there’s nothing further I can do to treat your cancer.22 Apart from being open and honest with their patients, physicians did not want to disappoint their patients by not helping them or by taking away their hope by giving them ‘nothing.’ – Study Authors57 GPs [general practitioners] also felt it extremely difficult to object to external life-preserving viewpoints. When the patient’s/family’s view differed from the GP’s opinion or when the patient/family appeared not to be ready for the approaching loss, the GP would succumb. – Study authors46 Patients' families often have unrealistic expectations...[The provision of futile treatment] will probably come down to how forthright or aggressive the family are and also come down to the doctor's ability to deal with that. Their confidence or their courage of conviction.23 |

| Personal values favoring life extension |

…I believe in the sanctity of life, and will always try to prolong it, even if its quality is low.56 ...I see it all the time...when those doctors, devout doctors, who have a strong right to life, when they are practising on their own without any integration with any other doctors, then they can go on clearly without any interference on their futile way.23 I think it was a personal philosophy of the other provider that they simply don’t withdraw—a religious, a little more broadly defined, a set of (ethical) beliefs that (the decision to withdraw life support) is not a decision we should be making.47 Some physicians just simply do not believe that withdrawal of life support is appropriate in any circumstance—that it is a disrespect of life.47 Withholding ANH [artificial nutrition and hydration; at the end of life] constitutes an act of abuse. You know it directly leads to death and this is the same as letting babies die without giving food.53 |

| Decisional avoidance |

If there is only the slightest uncertainty, it may feel hard to make a decision and therefore one chooses to defer it.60 The respondents described personality in terms of differences in how pragmatic and realistic intensivists were and how they differed concerning decisiveness and certainty regarding ELDM [end-of-life decision-making]. – Study authors31 Somehow there is a blockade in your head. There is no other reason for it other than the fear that you could perhaps do something wrong.41 Doctors reported wanting to give patients the "benefit of the doubt" and were motivated to continue treating out of fear of making the wrong decision23 |

| Over-optimism |

…you are always thinking you can pull some rabbit out of the hat; you tend to think that something is going to work.61 I think we should be able to offer them that [additional treatment options], because some of the times, you are going to hit a home run, or at least a double where you can prolong their life significantly.49 We always hope that this particular case won’t be bad, this particular case will shine. This will be the one that all the bad things don’t happen to.48 I wish I had been able to say, ‘Let’s not pursue chemotherapy,’ but at the same time, it was just that, what if? What if, what if, what if?22 |

All quotes from study participants unless indicated as from study authors

Professional Identity as “Fixer”

This theme pertained to how physicians saw their role and job in the care of patients with advanced life-limiting illness.41–43 Some physicians may see their professional identity and role more so as that of curing disease and extending life, and providing treatments and procedures to achieve such ends.22,23,43–45 Decisions for lower end-of-life care intensity require physicians to step away from the role of providing life-extending care to one of providing palliative or comfort care, and some physicians find this more challenging than others. Overemphasis on the “fixer” identity may result in undue attention given to treatments that can be performed to extend the patients’ life, and overlook the benefit of comfort-focused care approaches.41–43,46,47 The identity as a treater may result in a greater proclivity to “offer something” that extends life, even when the clinical context is one where there may not be any specific treatments to be done or a clear “fix” to be pursued.

…it’s all about we need to fix things, and we need to, you know, cure things…we sometimes lose sight of the fact that we can’t actually fix everything.42

The extracted data spoke to how, depending on physicians’ professional identity, being faced with patients’ illness progression may elicit different subjective reactions. When the identity is that of a “treater,” the physician may be more likely to experience feelings of personal- or role-failure, due to the sense of not fulfilling or living up to one’s expected role.22,48–50 This sense of personal- or role-failure may be associated with feelings such as disappointment, powerlessness, a sense of “battle lost” or “giving up.”51,52 Such feelings make it more likely to consider default, life-extending treatment options and less likely to consider de-prescribing, de-escalation or withholding of life-extending treatments.

Nephrologists expressed feeling like patients’ deaths reflected their own failure.50

Mortality Aversion

This theme pertained to the distress, unpleasantness, and negative arousal experienced by the physician when bearing witness to their patients’ illness progression, suffering, misfortune, and mortality.22,45,53–56 In the previous theme, negative psychological states (e.g., sense of failure) result from not living up to one’s professional role. In mortality aversion, negative psychological states result from witnessing the decline and demise of another human being, particularly someone that the physician may have known or could relate to. The data spoke to how physicians may be saddened or feel upset by their patients’ advancing illness, and how these emotions are accentuated when they have a closer relationship with the patient, or when they can more easily relate to the patient’s predicament, due to having similar life circumstances or shared propensities (e.g., being of the same age; both having young children).24,43,45,49,57–62 Such greater experienced emotional unpleasantness may make it harder to consider choices to de-escalate or withhold life-extending treatments or refer to hospice.

[Not initiating dialysis] is very difficult because... you’re watching people die, which is inherently stressful, and you do know you could reverse [it] for a few months...You feel compelled to offer it.50

Communication Avoidance

This theme highlighted the variability between physicians in the extent to which they were inclined to have discussions regarding dying and goals of care with patients and their families. As decisions regarding end-of-life care intensity need to be made in conjunction with patient/family, this theme highlighted how differences in physicians’ inclination for end-of-life discussions could lead to variability in end-of-life care intensity received by their patients.22,23,43,44,50,63,64 Specifically, some physicians may be more interested, willing, and comfortable in having difficult conversations than other physicians, who find such conversations to be more challenging and psychologically burdensome. Continuing treatments may provide a means to avoid the difficult discussions.22–24,43,63 Thus, being more disinclined for end-of-life care discussions may lead to higher treatment intensity directly by influencing the physicians own decision to pursue life-extending treatments, or indirectly via patient/family decisions, as the lack of goals of care discussions may leave patient/family less ready or with less opportunity to make decisions regarding de-escalating treatments.

It’s a hell of a lot easier conversation to say, ‘Alright, let’s do your next round of chemo. I’ll see you in 3 weeks,’ rather than have a conversation to say I don’t think we should do more chemo22

Conflict Avoidance

Several studies discussed how the end-of-life care context is often one where the physician had “bad news” or treatment suggestions that ran counter to patient/family wishes.22,51,57 In such a context, variability between physicians in the extent to which they want to appease or please the patient/family may translate to different intensity of care received by their patients.23,44,46,58,63,65,66 Some physicians may find it more difficult to disappoint or upset the patient/family, and may be more motivated to avoid conflict.22,43 Consequently, such physicians may be more likely to delay treatment decisions and conversations that are difficult for patients/family, or concede to patient/family requests for further life-extending treatments against their own best judgment.23,46,57

Some doctors believed it was easier to tread ‘the path of least resistance’ and provide care to placate families23

Personal Values Favoring Life Extension

Decision-making regarding end-of-life treatment intensity often occurs under conditions of uncertainty, with no clear medically superior choice. Uncertainty may provide room for physicians’ personal values about the prioritization of life-extension relative to quality-of-life to be inserted into the decisions made.53,54,56,62,64 These values have implications for level of treatment intensity provided. The extracted data cited examples of personal beliefs and values, stemming from either secular or religious sources, that influence treatment intensity decisions.23,45,47,51,56,59,64,67 Such values pertained to specific treatment procedures as well as broad approaches to end-of-life care (e.g., “withholding ANH [artificial nutrition/hydration] constitutes an act of abuse;”53 “some physicians just simply do not believe that withdrawal of life support is appropriate in any circumstance”47). Such personal values may shape how a physician reasons regarding treatment decisions.

I think it was a personal philosophy of the other provider that they simply don’t withdraw—a religious, a little more broadly defined, a set of [ethical] beliefs that [the decision to withdraw life support] is not a decision we should be making.47

Decisional Avoidance

End-of-life care intensity decisions were often made under conditions of significant uncertainty.22,23,48,50,60 Decisional avoidance pertained to the tendency to deal with such uncertainty by avoiding or deferring a treatment decision. Physicians who are more prone to decisional avoidance may be more likely to rely on the default option and maintain the status quo.23,31,41,42,60 In most non-palliative end-of-life care context, the default option involves providing or continuing life-extending treatments. Consequently, decisional avoidance would be associated with higher treatment intensity.

If there is only the slightest uncertainty, it may feel hard to make a decision and therefore one chooses to defer it.60

Over-optimism

In several studies, optimistic bias was also observed in how physicians reasoned about treatments in the face of uncertainty.22,41,48,57 Some studies indicated how physicians may err on the side of “what if” treatments work, reasoning that they could perhaps beat the odds and achieve an unlikely, but preferred outcome.22–24,49,50 Thus, in situations of uncertainty, or even unlikely positive outcome, they took the approach of giving it a “try.”45,57 Optimistically biased thinking would result in those physicians more often making decisions favoring life-extending treatments.

…you are always thinking you can pull some rabbit out of the hat; you tend to think that something is going to work.61

DISCUSSION

This review synthesized qualitative findings on psychological propensities that could result in some physicians providing more life-extending treatment than others. Our findings indicate that care-intensity at the end-of-life could reflect differences in physicians’ professional identity, mortality aversion, communication avoidance, conflict avoidance, personal values favoring life extension, decisional avoidance, and over-optimism. Such differences can lead to significant differences in judgments about whether and when to de-escalate life-extending treatments. Put simply, psychological propensities can be consequential for physicians’ care decisions.2,18,19 Psychological propensities therefore warrant further consideration in both theoretical and applied work.

The notion that psychological propensities could shape physicians’ care decisions is not a new idea.18,19 However, it has yet to be adequately examined and leveraged. For example, prominent theoretical models of healthcare utilization have entirely left out the treating physician as a relevant factor, with the implicit assumption that characteristics of the treating physician would have no bearing on the quality and nature of care provided.68,69 While subsequent iterations of these models have tried to account for the treating physician, such revisions have been limited largely to demographic factors or broad categorizations related to the physician, such as the physician’s race or gender.70 More recent research has quantitatively demonstrated that attributes of the treating physician in fact do account for a substantial proportion of the variability seen in end-of-life care intensity,1,6–8 with many qualitative studies identifying psychological propensities that could account for observed physician-attributable variability. The present review synthesized this relevant qualitative literature on end-of-life care intensity, explicating how psychological propensities may translate to differences in treatment intensity decisions of the treating physician.

The present results raise the possibility that addressing psychological propensities could reduce physician-attributed variation in care.2,71 In fact, this is a basic premise for self-awareness skills curriculum being added to medical education,32,33 where medical students are trained on being cognizant of how their sense of self (beliefs, values, emotions) can impact the care that they provide to their patients. Similarly, Balint groups and Schwartz rounds have been implemented in many care settings, where groups of practitioners discuss challenging cases to support one another on psychologically difficult aspects of patient care.72–74 However, the specificity of the psychological propensities that arose in the present findings suggests that more focused, structured group formats centered around addressing specific propensities—as opposed to providing general peer support—may be even more beneficial. Future research should therefore explore whether more focused approaches leveraging reflection, mindfulness, and peer support regarding specific psychological propensities could have more potent effects than existing approaches centered around general support. Another crucial consideration in addressing psychological propensities are the larger socio-cultural institutions that physicians are embedded in. Physicians’ psychological propensities are shaped by medical education, healthcare delivery systems, and incentive structures.32,33,75 Modifying these institutional structures could therefore result in changes in physician psychological propensities and corresponding care patterns.

Specifically, for interventions aiming to reduce low-value end-of-life care intensity, the present review points to potential future directions. Current approaches to physician-focused interventions for end-of-life care intensity consist of electronic health record-based alerts to physicians (e.g., prompts to carry out end-of-life care conversations) or communication skills training (e.g., training on carrying out end-of-life conversations using the Serious Illness Conversation Guide).76–79 Future research should examine the extent to which such behavioral “nudges” and skill provision are sufficient in addressing physician-attributable variability seen in end-of-life care intensity. Given that many of the psychological propensities identified in the present review involved elements such as identity, values, and strong emotions, future research should examine if more psychoactive interventions altering physicians’ cognitions, awareness, and emotional experience will provide added value. For instance, peer group sessions encouraging physician reflection on how aspects of their professional identity, values, and experienced emotions influence treatment decisions, and increasing emotion regulation skills pertaining to patient mortality, could potentially change treatment intensity decisions.33,71 Such trainings have been developed in other settings such as primary care, where a mindfulness and self-awareness-based intervention was shown to enhance physicians’ well-being and attitudes towards patient care,34 but to our knowledge such interventions have yet to be developed addressing end-of-life care intensity.

It is worth considering how self-selection effects may amplify the effects of psychological propensities on patient outcomes. There is evidence for self-selection in employment settings, such that individuals are more likely to choose medical specialties, subspecialties, and treatment settings that are congruent with their psychological propensities.80,81 Such self-selection effects would lead to greater homogeneity between individuals within certain practice settings, possibly resulting in multiplier effects and amplifying the influence of psychological propensities on end-of-life treatment intensity in particular treatment settings.

Given the central role of interactions with patients and families in some of the identified psychological propensities, it is worth considering how existing patient and family support interventions at the end-of-life (e.g., coping support and goals-of-care conversations from specialty palliative care) may affect the physicians caring for those patients. Such interventions may alleviate some of the treating physician’s experienced psychological challenges in de-escalation of care. It is also important to acknowledge that while our included studies focused primarily on physicians, advanced practice providers are increasingly involved with end-of-life care intensity decisions, and it is unclear to what extent the identified psychological propensities may be similar for those providers. As medical school education, professional socialization, and peer norms may influence psychological propensities, there may be differences in the propensities of physicians relative to different advanced practice providers, and future research should explore this question.

There are limitations to the present systematic review. The qualitative nature of the included studies means that the findings should be seen as hypothesis-generating, and further empirical work is needed. For example, quantitative examinations—such as factor analysis using physician survey data—could examine if the seven themes identified here can be quantitatively validated as a distinct phenomenon, or whether they are better conceptualized into a broader, smaller number of domains. Notably, four of the themes identified here centered around avoidance or aversion (mortality aversion, communication avoidance, conflict avoidance, and decisional avoidance) and two centered around valuing of life extension (professional identity as “fixer” and personal values favoring life extension). Future research could therefore explore the most empirically robust categorizations of psychological propensities and their links with treatment decision-making. Another limitation of the present systematic review includes the diversity of care settings and decisional contexts examined among the included studies (e.g., decisions regarding chemotherapy vs. artificial nutrition; cancer vs. renal disease). Some of these contexts were overrepresented, such as studies within cancer. Some of the contexts involved treatment of children and neonates, which may evoke different psychological propensities relative to the treatment of adults. As the present analysis pooled across different care contexts, it is possible that the identified psychological propensities may not be uniformly relevant across care contexts. Finally, our review only consisted of English-language references and many of the included studies were done in the USA, which may undermine generalizability of findings to other countries with different socio-cultural contexts and approaches to healthcare delivery.

CONCLUSION

The present synthesis explicates how psychological propensities could influence physicians’ judgments regarding whether and when to withhold or de-escalate life-extending treatments. Given that end-of-life care intensity has been identified as a major source of low-value healthcare expenditure,82 further work is needed on leveraging psychological propensities to reduce physician-attributed variation in end-of-life care intensity, including physician-focused interventions and changes to medical education.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 21 kb)

Funding

Supported by the National Cancer Institute (R00 CA241310, P30CA072720-5931) and the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cutler D, Skinner JS, Stern AD, Wennberg D. Physician beliefs and patient preferences: A new look at regional variation in health care spending. Am Econ J Econ Policy. 2019;11(1):192-221. 10.1257/pol.20150421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Wilkinson DJ, Truog RD. The luck of the draw: physician-related variability in end-of-life decision-making in intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(6):1128-32. 10.1007/s00134-013-2871-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Wang X, Knight LS, Evans A, Wang J, Smith TJ. Variations among physicians in hospice referrals of patients with advanced cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(5):e496-e504. 10.1200/jop.2016.018093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Larochelle MR, Rodriguez KL, Arnold RM, Barnato AE. Hospital staff attributions of the causes of physician variation in end-of-life treatment intensity. Palliat Med. 2009;23(5):460-70. 10.1177/0269216309103664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Sinaiko AD, Chien AT, Hassett MJ, et al. What drives variation in spending for breast cancer patients within geographic regions? Health Serv Res. 2019;54(1):97-105. 10.1111/1475-6773.13068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Fang P, Jagsi R, He W, et al. Rising and falling trends in the use of chemotherapy and targeted therapy near the end of life in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(20):1721-1731. 10.1200/jco.18.02067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kao S, Shafiq J, Vardy J, Adams D. Use of chemotherapy at end of life in oncology patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(9):1555-1559. 10.1093/annonc/mdp027. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Obermeyer Z, Powers BW, Makar M, Keating NL, Cutler DM. Physician characteristics strongly predict patient enrollment in hospice. Health Aff. 2015;34(6):993-1000. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Garland A, Connors AF. Physicians' influence over decisions to forego life support. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(6):1298-305. 10.1089/jpm.2007.0061. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Chen AB, Niu J, Cronin AM, Shih YT, Giordano S, Schrag D. Variation in use of high-cost technologies for palliative radiation therapy by radiation oncologists. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2021;19(4):421-431. 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.De Schreye R, Houttekier D, Deliens L, Cohen J. Developing indicators of appropriate and inappropriate end-of-life care in people with Alzheimer's disease, cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for population-level administrative databases: A RAND/UCLA appropriateness study. Palliat Med. 2017;31(10):932-945. 10.1177/0269216317705099. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Henson LA, Edmonds P, Johnston A, et al. Population-based quality indicators for end-of-life cancer care: A systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(1):142-150. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3388. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Duberstein PR, Chen M, Hoerger M, et al. Conceptualizing and counting discretionary utilization in the final 100 days of life: A scoping review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(4):894-915.e14. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(6):778-84. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987-94. 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lambden JP, Chamberlin P, Kozlov E, et al. Association of perceived futile or potentially inappropriate care with burnout and thoughts of quitting among health-care providers. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®. 2019/03/01 2018;36(3):200-206. 10.1177/1049909118792517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Long AC, Brumback LC, Curtis JR, et al. Agreement with consensus statements on end-of-life care: A description of variability at the level of the provider, hospital, and country. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(10):1396-1401. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Staudenmayer H, Lefkowitz MS. Physician-patient psychosocial characteristics influencing medical decision-making. Soc Sci Med E. 1981;15(1):77-81. 10.1016/0271-5384(81)90066-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Eisenberg JM. Sociologic influences on decision-making by clinicians. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90(6):957-64. 10.7326/0003-4819-90-6-957. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Pines JM, Hollander JE, Isserman JA, et al. The association between physician risk tolerance and imaging use in abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(5):552-7. 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Katz DA, Mello MM. High physician concern about malpractice risk predicts more aggressive diagnostic testing in office-based practice. Health Aff. 2013;32(8):1383-91. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0233. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Bluhm M, Connell CM, De Vries RG, Janz NK, Bickel KE, Silveira MJ. Paradox of prescribing late chemotherapy: Oncologists explain. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(12):e1006-e1015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Willmott L, White B, Gallois C, et al. Reasons doctors provide futile treatment at the end of life: a qualitative study. J Med Ethics. 2016;42(8):496-503. 10.1136/medethics-2016-103370. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Laryionava K, Heusner P, Hiddemann W, Winkler EC. "Rather one more chemo than one less...": Oncologists and oncology nurses' reasons for aggressive treatment of young adults with advanced cancer. Oncologist. 2018;23(2):256-262. 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Ridley S, Fisher M. Uncertainty in end-of-life care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013;19(6):642-647. 10.1097/mcc.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Smith AK, Fisher J, Schonberg MA, et al. Am I doing the right thing? Provider perspectives on improving palliative care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(1):86-93, 93.e1. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kaufman SR, Shim JK, Russ AJ. Revisiting the biomedicalization of aging: Clinical trends and ethical challenges. Gerontologist. 2004;44(6):731-8. 10.1093/geront/44.6.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Oken D. What to tell cancer patients. A study of medical attitudes. JAMA. 1961;175:1120-8. 10.1001/jama.1961.03040130004002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Mack JW, Smith TJ. Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(22):2715-7. 10.1200/jco.2012.42.4564. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Bories P, Lamy S, Simand C, et al. Physician uncertainty aversion impacts medical decision making for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Results of a national survey. Haematologica. 2018;103(12):2040-2048. 10.3324/haematol.2018.192468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Nordenskjold Syrous A, Malmgren J, Odenstedt Herges H, et al. Reasons for physician-related variability in end-of-life decision-making in intensive care. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021;65(8):1102-1108. 10.1111/aas.13842. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Novack DH, Epstein RM, Paulsen RH. Toward creating physician-healers: Fostering medical students' self-awareness, personal growth, and well-being. Acad Med. 1999;74(5):516-20. 10.1097/00001888-199905000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Novack DH, Suchman AL, Clark W, Epstein RM, Najberg E, Kaplan C. Calibrating the physician. Personal awareness and effective patient care. Working Group on Promoting Physician Personal Awareness, American Academy on Physician and Patient. JAMA. 1997;278(6):502-9. 10.1001/jama.278.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284-93. 10.1001/jama.2009.1384. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Luta X, Maessen M, Egger M, Stuck AE, Goodman D, Clough-Gorr KM. Measuring intensity of end of life care: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0123764. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Neergaard MA, Brunoe AH, Skorstengaard MH, Nielsen MK. What socio-economic factors determine place of death for people with life-limiting illness? A systematic review and appraisal of methodological rigour. Palliat Med. 2019;33(8):900-925. 10.1177/0269216319847089. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Shrestha S, Poudel A, Steadman K, Nissen L. Outcomes of deprescribing interventions in older patients with life-limiting illness and limited life expectancy: A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(10):1931-1945. 10.1111/bcp.14113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Programme CAS. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- 40.Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C. Focus on qualitative methods. Qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and techniques. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(4):365-71. 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199708)20:4<365::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Jox RJ, Schaider A, Marckmann G, Borasio GD. Medical futility at the end of life: The perspectives of intensive care and palliative care clinicians. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(9):540-545. 10.1136/medethics-2011-100479. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Kryworuchko J, Strachan PH, Nouvet E, Downar J, You JJ. Factors influencing communication and decision-making about life-sustaining technology during serious illness: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e010451. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Broom A, Kirby E, Good P, Wootton J, Adams J. The art of letting go: Referral to palliative care and its discontents. Social Sci Med (1982). 2013;78(ut9, 8303205):9-16. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Dzeng E, Dohan D, Curtis JR, Smith TJ, Colaianni A, Ritchie CS. Homing in on the Social: System-level influences on overly aggressive treatments at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):282-289.e1. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Robertsen A, Helseth E, Laake JH, Forde R. Neurocritical care physicians' doubt about whether to withdraw life-sustaining treatment the first days after devastating brain injury: An interview study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019;27(1):81. 10.1186/s13049-019-0648-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Sercu M, Renterghem VV, Pype P, Aelbrecht K, Derese A, Deveugele M. "It is not the fading candle that one expects": General practitioners' perspectives on life-preserving versus "letting go" decision-making in end-of-life home care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(4):233-42. 10.3109/02813432.2015.1118837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Wilson ME, Rhudy LM, Ballinger BA, Tescher AN, Pickering BW, Gajic O. Factors that contribute to physician variability in decisions to limit life support in the ICU: A qualitative study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(6):1009–18. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Catlin AJ, Stevenson DK. Physicians' neonatal resuscitation of extremely low-birth-weight preterm infants. Image J Nurs Sch. 1999;31(3):269-75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Marmo S. Recommendations for hospice care to terminally ill cancer patients: A phenomenological study of oncologists' experiences. J Soc Work End-Of-Life Palliat Care. 2014;10(2):149-69. 10.1080/15524256.2014.906373. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Wachterman MW, Leveille T, Keating NL, Simon SR, Waikar SS, Bokhour B. Nephrologists' emotional burden regarding decision-making about dialysis initiation in older adults: A qualitative study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):385. 10.1186/s12882-019-1565-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Fadadu PP, Liu JC, Schiltz BM, et al. A Mixed-methods exploration of pediatric intensivists' attitudes toward end-of-life care in vietnam. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(8):885-893. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0496. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Ozeki-Hayashi R, Fujita M, Tsuchiya A, et al. Beliefs held by breast surgeons that impact the treatment decision process for advanced breast cancer patients: A qualitative study. Breast Cancer. 2019;11(101591856):221-229. 10.2147/BCTT.S208910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Aita K, Takahashi M, Miyata H, Kai I, Finucane TE. Physicians' attitudes about artificial feeding in older patients with severe cognitive impairment in Japan: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics. 2007;7(100968548):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Asai A, Fukuhara S, Inoshita O, Miura Y, Tanabe N, Kurokawa K. Medical decisions concerning the end of life: A discussion with Japanese physicians. J Med Ethics. 1997;23(5):323-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Bluhm M, Connell CM, Janz N, Bickel K, Devries R, Silveira M. Oncologists' end of life treatment decisions: How much does patient age matter? J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36(4):416-440. 10.1177/0733464815595510. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Carmel S. Behavior, attitudes, and expectations regarding the use of life-sustaining treatments among physicians in Israel: An exploratory study. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(6):955-65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Buiting HM, Rurup ML, Wijsbek H, van Zuylen L, den Hartogh G. Understanding provision of chemotherapy to patients with end stage cancer: Qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2011;342(8900488, bmj, 101090866):d1933. 10.1136/bmj.d1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Callaghan KA, Fanning JB. Managing bias in palliative care: Professional hazards in goals of care discussions at the end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(2):355-363. 10.1177/1049909117707486. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Dupont-Thibodeau A, Hindie J, Bourque CJ, Janvier A. Provider perspectives regarding resuscitation decisions for neonates and other vulnerable patients. J Pediatr. 2017;188(jlz, 0375410):142-147.e3. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Nordenskjold Syrous A, Agard A, Kock Redfors M, Naredi S, Block L. Swedish intensivists' experiences and attitudes regarding end-of-life decisions. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020;64(5):656-662. 10.1111/aas.13549. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Odejide OO, Coronado DYS, Watts CD, Wright AA, Abel GA. Focus on Quality. End-of-life care for blood cancers: A series of focus groups with hematologic oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(6):e396-403. 10.1200/JOP.2014.001537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Schildmann J, Tan J, Salloch S, Vollmann J. "Well, I think there is great variation...": A qualitative study of oncologists' experiences and views regarding medical criteria and other factors relevant to treatment decisions in advanced cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18(1):90-6. 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.St Clair Russell J, Oliverio A, Paulus A. Barriers to conservative management conversations: Perceptions of nephrologists and fellows-in-training. J Palliat Med. 2021;(d0c, 9808462). 10.1089/jpm.2020.0690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Haliko S, Downs J, Mohan D, Arnold R, Barnato AE. Hospital-based physicians' intubation decisions and associated mental models when managing a critically and terminally ill older patient. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(3):344-354. 10.1177/0272989X17738958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Lotz JD, Jox RJ, Meurer C, Borasio GD, Führer M. Medical indication regarding life-sustaining treatment for children: Focus groups with clinicians. Palliat Med. 2016;30(10):960-970. 10.1177/0269216316628422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Mobasher M, Nakhaee N, Tahmasebi M, Zahedi F, Larijani B. Ethical issues in the end of life care for cancer patients in iran. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(2):188–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Padela AI, Shanawani H, Greenlaw J, Hamid H, Aktas M, Chin N. The perceived role of Islam in immigrant Muslim medical practice within the USA: An exploratory qualitative study. J Med Ethics. 2008;34(5):365-369. 10.1136/jme.2007.021345. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. Winter 1973;51(1):95-124. [PubMed]

- 69.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1-10. [PubMed]

- 70.Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: Assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Serv Res. 1998;33(3 Pt 1):571-96. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Panagopoulou E, Mintziori G, Montgomery A, Kapoukranidou D, Benos A. Concealment of information in clinical practice: Is lying less stressful than telling the truth? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(7):1175-7. 10.1200/jco.2007.12.8751. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Roberts M. Balint groups: A tool for personal and professional resilience. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(3):245-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Van Roy K, Vanheule S, Inslegers R. Research on Balint groups: A literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(6):685-94. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Lown BA, Manning CF. The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. 2010;85(6):1073-81. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dbf741. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Duberstein P, Meldrum S, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Epstein RM. Influences on patients' ratings of physicians: Physicians demographics and personality. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(2):270-4. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Haley EM, Meisel D, Gitelman Y, Dingfield L, Casarett DJ, O'Connor NR. Electronic goals of care alerts: An innovative strategy to promote primary palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):932-937. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.329. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Courtright KR, Dress EM, Singh J, et al. Prognosticating outcomes and nudging decisions with electronic records in the intensive care unit trial protocol. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(2):336-346. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202002-088SD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al. Effect of a patient-centered communication intervention on oncologist-patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer: The voice randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):92-100. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. Effect of the Serious Illness Care Program in outpatient oncology: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):751-759. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Borges NJ, Savickas ML. Personality and medical specialty choice: A literature review and integration. J Career Assess. 2002;10(3):362-380. 10.1177/10672702010003006

- 81.Taber BJ, Hartung PJ, Borges NJ. Personality and values as predictors of medical specialty choice. J Vocat Behav. 2011;78(2):202-209. 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.09.006

- 82.Issues IoMCoADAKE-o-L. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 21 kb)