Abstract

A flow cytometric technique was developed for detection of amastigotes of the protozoan Leishmania infantum in human nonadherent monocyte-derived macrophages. The cells were fixed and permeabilized with paraformaldehyde-ethanol, and intracellular amastigotes were labeled with Leishmania lipophosphoglycan-specific monoclonal antibody. Results showed that flow cytometry provided accurate quantification of the infection rates in human macrophages compared to the rates obtained by the conventional microscopic technique, with the advantage that a large number of cells could be analyzed rapidly. The results demonstrated, moreover, that labeling of intracellular amastigotes could reliably be used to evaluate the antileishmanial activities of conventional drugs such as meglumine antimoniate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, and allopurinol. They also established that various Leishmania species (L. mexicana, L. donovani) could be detected by this technique in other host-cell models such as mouse peritoneal macrophages and suggested that the flow cytometric method could be a valid alternative to the conventional method.

Leishmaniases are vector-borne parasitic diseases caused by protozoa of the genus Leishmania. These obligate intracellular parasites replicate in the parasitophorus vacuoles of macrophages (3, 6) and produce life-threatening disorders widely distributed in tropical, subtropical, and Mediterranean countries (Division of Control of Tropical Diseases, World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/ctd/html/leish.html). Several clinical syndromes are subsumed under the term leishmaniasis according to the localization of the parasites in mammalian tissues, notably, visceral, cutaneous, and mucosal leishmaniases. Parasites of the species Leishmania infantum, identified as a causative agent of the visceral form of leishmaniasis, have been shown to be endemic in France (Division of Control of Tropical Diseases, World Health Organization).

Since the 1940s, the generally accepted therapy for all forms of leishmaniasis consisted of pentavalent antimonial agents, used as first-line clinical treatment (7, 23); however, antileishmanial therapy has been a bewildering subject largely because of the complexity of the disease. Moreover, the recent appearance of clinical resistance to meglumine antimoniate (8, 13) and the small number of efficient second-line antileishmanial drugs raised the necessity to develop new methods for the rapid assessment of the antileishmanial activities of chemical compounds.

Various in vitro host-cell models such as mouse peritoneal macrophages (4), human monocytes (U-937) (16), or Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (26) have been created to study infection of mammalian cells with Leishmania parasites and to test the antileishmanial activities of new molecules. In these models, infection rates were usually measured by microscopic examination of adherent cells. In 1992, Ogunkolade et al. (20) developed an in vitro model that permitted infection of human monocyte-derived macrophages (THP1 cell line) by various species of Leishmania. This technique presented the advantage that adherent as well as free cells could be obtained easily and could be infected in vitro by the promastigote stage of the parasite. On the other hand, recent developments demonstrated that flow cytometry could be used to study infection of mammalian cells by various Leishmania species and established that amastigote-containing macrophages could reliably be separated from noninfected cells by immunofluorescence staining (1, 2, 5; B. Goullin, F. Belloc, P. Dumain, T. Masseron, F. Lacombe, and J. J. Floch, Biol. Cell. 76:276, 1992, abstract).

In the present study, we investigated the possibility of using flow cytometry for the rapid and reliable detection of possible antileishmanial drugs. For this purpose, we first developed a flow cytometric assay based on the staining of intracellular amastigotes with a lipophosphoglycan (LPG)-specific monoclonal antibody in nonadherent human monocyte-derived macrophages, and then we estimated the capacity of the technique to detect antileishmanial agents by assessing the antileishmanial activities of conventional drugs such as meglumine antimoniate, pentamidine, allopurinol, and amphotericin B against parasites of the species L. infantum. Furthermore, we tested the ability of the technique to assess the meglumine antimoniate susceptibilities of various Leishmania species such as L. mexicana and L. donovani in other host cells such as mouse peritoneal macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

Experiments were performed with reference strains L. infantum MHOM/FR/78/LEM75, L. mexicana MHOM/MX/95/NAN1, and L. donovani LM83. Parasites were cultivated in RPMI medium (Eurobio, Paris, France) supplemented with 15% heat-decomplemented fetal calf serum (Eurobio). Incubation was performed at 25°C, and promastigotes replicated every 5 days.

Host cells.

Assays were conducted with human monocytes (THP1 cells) and peritoneal mouse macrophages. THP1 cells were cultured by the methodology previously described by Ogunkolade et al. (20). Human monocytes were maintained in RPMI medium (Eurobio) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (Eurobio) at 37°C in 5% CO2 and replicated every 7 days. Maturation of adherent macrophages was achieved by treating exponentially growing cultures (105 cells/ml) with 1 μM phorbol myristate acetate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) for 48 h at 37°C in Lab Tek chamber-slides (Fisher, Paris, France), while maturation in nonadherent macrophages was performed by treating exponentially growing cultures (106 cells/ml) with 1 mM retinoic acid (Sigma) for 72 h at 37°C.

Mouse macrophages were recovered from unstimulated BALB/c mice after peritoneal washings with RPMI medium. Adherent macrophages were obtained by transferring mouse peritoneal cells to Lab Tek chamber slides (Fisher). The cells were incubated in RPMI medium (Eurobio) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (Eurobio) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 hours. Nonadherent mouse macrophages were obtained by incubating mouse peritoneal cells in polystyrene suspension-special flasks (Fisher). The cells were incubated in RPMI medium (Eurobio) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (Eurobio) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h.

Antileishmanial agents.

Meglumine antimoniate was dissolved in sterile water and was stored at 4°C. Amphotericin B, pentamidine, and allopurinol (Sigma) were dissolved in sterile dimethyl sulfoxide (analytical grade; Sigma) and were stored frozen at −70°C until used.

Standard assays with adherent macrophages.

Macrophages were rinsed with fresh medium and were suspended in RPMI medium containing stationary-phase Leishmania promastigotes (cell/promastigote ratio, 1/10). After a 24-h period of incubation at 37°C, the promastigotes were removed by four successive washes with fresh medium. Adapted dilutions of drugs were added to duplicate chambers, and the cultures were incubated for 96 h at 37°C. The cells were harvested with analytical-grade methanol (Sigma) and stained with 10% Giemsa stain (Eurobio). The percentage of infected macrophages in each assay was determined microscopically at ×1,000 magnification.

Standard assays with nonadherent macrophages.

Macrophages were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min and were suspended in RPMI medium containing stationary-phase promastigotes (cell/promastigote ratio, 1/10). After a 24-h period of incubation at 37°C, the promastigotes were removed by three successive centrifugations (100 × g), followed by washes in fresh medium. Adapted dilutions of drugs were added to duplicate cultures, and the cultures were incubated for 96 h at 37°C. At the end on the incubation period, the cells were centrifuged (400 × g) for 5 min and the pellets were fixed in 70% analytical-grade methanol (Sigma). Two or three drops of each suspension were transferred onto microscope slides and stained for 5 min in 5% Giemsa (Eurobio). The percentage of infected macrophages in each assay was determined microscopically at ×1,000 magnification.

Immunofluorescence staining of intracellular parasites in nonadherent macrophages.

At the end of the incubation period, cell suspensions were harvested by incubation for 60 to 90 min in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Eurobio) containing 1% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) at ambient temperature. After a 5-min centrifugation (400 × g), permeabilization of the membranes and parasitophorus vacuoles was performed by suspending the cells in analytical-grade ethanol (Sigma) for 60 to 90 min at −20°C. After washing with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) in PBS, the cells were incubated for 60 to 90 min at 4°C in Leishmania LPG-specific monoclonal antibody (Tebu, Paris, France) diluted 1/250. After three successive washes in PBS-BSA buffer, the intracellular amastigotes were stained with 1 μM fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G whole molecule (Sigma) for 60 min at 4°C. The cells were rinsed in PBS-BSA buffer and were stored at 4°C in the dark until analysis.

Flow cytometry.

The cells were run on a FacSort analytical flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Paris, France) equipped with a 15-mV, 488-nm air-cooled argon ion laser. The optimized instrument parameters were as follows: for forward scatter, voltage, E-1; gain, 1; and mode, log; for side scatter, voltage, 250; gain, 1; mode, log; and for fluorescence 1, voltage, 250; gain, 1; mode, log. Cells were isolated from fragments by gating on the forward- and side-scatter signals, and then amastigote-containing macrophages were detected and sorted according to their relative fluorescence intensities compared to those of noninfected cells. Analyses were performed on 10,000 gated events, and numeric data were processed with Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis.

Comparison of the infection rates observed by microscopy and flow cytometry after various incubation periods for nonadherent macrophages was performed by the Mann and Whitney rank sum test. Comparison of data from 50 assays analyzed by microscopy and flow cytometry after a 96-h period of incubation was achieved by linear regression analysis. Antileishmanial activities were expressed as 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s), which illustrate the concentrations of drugs that produced a 50% reduction in the number of infected macrophages compared to the number of infected macrophages in control cultures. The IC50s were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis processed with the dose-response curves with Table Curve software (Jandel Scientific, Paris, France). Comparison of the IC50s obtained for adherent macrophages and nonadherent macrophages by microscopy and comparison of the IC50s measured by flow cytometry and microscopy for nonadherent macrophages were done by the Spearman rank correlation test. Coefficients of variation were calculated for the assessment of reproducibility. Each assay was done in duplicate, and 10 independent experiments were performed throughout the course of the study.

RESULTS

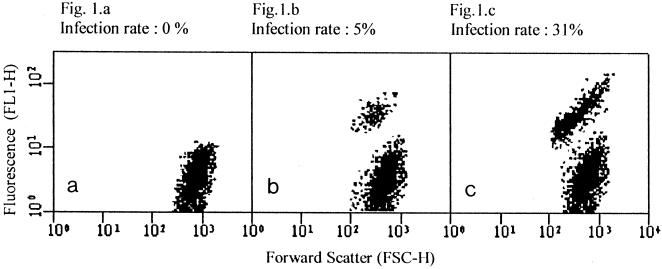

Examples of the flow cytometric analyses performed with nonadherent macrophages containing parasites at various rates of infection are presented in Fig. 1. The cytogram in Fig. 1a was acquired with noninfected macrophages; it reveals a homogeneous population identified by an average FL1-H green fluorescence lower than 10 units. The cytograms in Fig. 1b and 1c were acquired with Leishmania-macrophage cocultures. They display two well-defined populations discernible according to their relative fluorescences. Noninfected macrophages showed a weak fluorescence (lower than 10 units), while the relative fluorescence observed for amastigote-containing macrophages averaged more than 25 units. Cells were sorted according to their FL1-H fluorescences and were observed on a fluorescence microscope. More than 95% of the fluorescent cells were shown to contain at least one amastigote, while less than 2% of the nonfluorescent cells appeared to be infected with the protozoan parasite. Fluorescence microscopy also revealed that cells that contained one or two amastigotes displayed weaker fluorescence than cells that contained three or more amastigotes. However, amastigote-containing macrophages produced a homogeneous image on the cytogram, suggesting that the flow cytometric assay could not separate cells with more than one parasite from cells with a single parasite.

FIG. 1.

Examples of cytograms acquired with nonadherent monocyte-derived macrophages at various infection rates: 0% (a), 5% (b), and 31% (c).

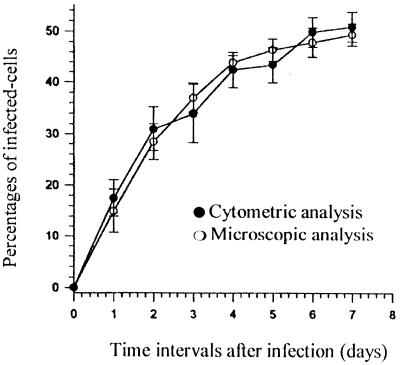

Comparison of the flow cytometric and microscopic estimates of the number of amastigote-containing macrophages after various incubation periods (1 to 7 days) measured in 10 independent assays is displayed in Fig. 2. The percentages of infected cells in nonadherent macrophages were shown to increase according to time intervals, whatever the method was used. Statistical comparison by the Mann and Whitney test (one-sided U test) demonstrated that no significant difference could be observed between infection rates measured by microscopy and cytometry for nonadherent macrophages at any time interval (P < 0.05), suggesting that LPG-specific antibodies could indifferently recognize early and late stages of the amastigote form of the parasite.

FIG. 2.

Evolution of infection rates in nonadherent monocyte-derived macrophages after various incubation periods as measured by cytometry and microscopy.

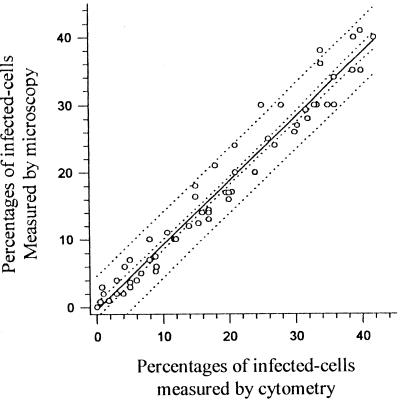

Figure 3 compares the percentages of infected cells measured by the microscopic and cytometric methods for nonadherent monocyte-derived macrophages after a 96-h period of incubation. The infection rates observed by the two methods were highly correlated (r = 0.971; P < 0.001).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of cytometric and microscopic analyses of infection rates in nonadherent monocyte-derived macrophage.

Table 1 summarizes the antiproliferative activities of conventional antileishmanial drugs (meglumine antimoniate, pentamidine, allopurinol, and amphotericin B) against intracellular L. infantum amastigotes. IC50s were measured by three methods: microscopic analysis of adherent macrophages, microscopic examination of nonadherent macrophages, and cytometric estimate of nonadherent macrophages. Comparison of microscopic analyses of adherent and nonadherent macrophages performed by the Spearman rank correlation test demonstrated that the antileishmanial activities of conventional drugs did not significantly differ, whatever host-cell model was used (z = 1.73; P < 0.05). Comparison of microscopic and cytometric analyses of nonadherent macrophages assumed that the antileishmanial activities of meglumine antimoniate, pentamidine, allopurinol, and amphotericin B did not significantly vary, whatever analytical method was used (z = 1.32; P < 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Activities of conventional antileishmanial agents observed against adherent and nonadherent monocytes by microscopy and cytometry

| Antileishmanial agent | IC50 (μg/ml) for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adherent macrophages | Nonadherent macrophages

|

||

| Measured by microscopy | Measured by cytometry | ||

| Meglumine antimoniate | 78 ± 12 | 53 ± 8 | 64 ± 15 |

| Pentamidine | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.09 | 0.38 ± 0.05 |

| Allopurinol | 42 ± 8 | 31 ± 6 | 37 ± 9 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.023 ± 0.004 | 0.036 ± 0.006 | 0.042 ± 0.008 |

Assessment of the meglumine antimoniate susceptibilities of nonadherent human monocyte-derived macrophages and mouse peritoneal macrophages determined by cytometric analysis compared to the susceptibilities determined by the standard microscopic technique with adherent cells is displayed in Table 2. The results demonstrated that Leishmania LPG-specific monoclonal antibodies could recognize species other than L. infantum. FITC-related relative fluorescence could also be detected in L. donovani and L. mexicana promastigotes, and detection of the corresponding intracellular amastigotes could be performed by the flow cytometric technique. Comparison of the meglumine antimoniate susceptibilities observed in human and mouse macrophages confirmed that the flow cytometric technique could also be used to evaluate Leishmania infection rates in peritoneal mouse macrophages and established that meglumine antimoniate susceptibility was weakly dependent on the host-cell system.

TABLE 2.

Assessment of meglumine antimoniate susceptibilities of organisms in nonadherent human monocyte-derived macrophages and mouse peritoneal macrophages determined by cytometric analysis compared to the those determined by the standard microscopic technique in adherent cells

| Organism | Relative fluorescence in promastigotes | Susceptibility (IC50 [μg/ml]) to meglumine antimoniate

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human THP1 cells

|

Mouse peritoneal macrophages

|

||||

| Microscopy | Cytometry | Microscopy | Cytometry | ||

| L. infantum | 864 | 72 ± 12 | 64 ± 15 | 69 ± 14 | 65 ± 7 |

| L. donovani | 712 | 45 ± 8 | 40 ± 6 | 38 ± 9 | 41 ± 8 |

| L. mexicana | 965 | 23 ± 8 | 19 ± 5 | 20 ± 8 | 21 ± 4 |

The results of analysis of flow cytometric reproducibility compared to the reproducibilities of conventional methods are shown in Table 3. The flow cytometric assay appeared to be more reproducible than the conventional methods.

TABLE 3.

Reproducibility of each antileishmanial assay

| Parameter | Infection rate (%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopic method with adherent macrophages

|

Microscopic method with nonadherent macrophages

|

Cytometric method with nonadherent macrophages

|

||||

| Negative controla | Positive controlb | Negative control | Positive control | Negative control | Positive control | |

| Mean value | 62 ± 8 | 30 ± 12 | 47 ± 7 | 28 ± 9 | 42 ± 6 | 22 ± 8 |

| Range | 55–78 | 24–36 | 43–51 | 18–30 | 38–49 | 19–31 |

| CVc (%) | 21.6 | 22.8 | 25.1 | 23.2 | 15.8 | 20.5 |

Sterile water.

Amphotericin B (0.03 μg/ml).

CV, coefficient of variation.

DISCUSSION

Flow cytometry consists of an automated means of single-cell multiparametric analysis at a rate of several hundreds of cells per second with high degrees of accuracy and reproducibility (10). Since 1975, various techniques based on the use of fluorescent probes have been developed to provide quantitative information on the structural and functional parameters reflecting cell behavior. These techniques have largely been used in the fields of medical science and cell biology (10). Recently, flow cytometry has been introduced in the medical field of parasitology for the study of human cells infected with protozoan parasites (11, 18, 19). Many reliable techniques are now extensively used to detect parasites of the genus Plasmodium in human red blood cells (22, 24), and various fluorescent probes or monoclonal antibodies have been developed for use in the exploration of interactions between parasites and host cells (21, 24).

Concerning Leishmania parasites, different techniques for the detection of intracellular amastigotes in mammalian cells have been proposed. In 1992, Goullin et al. (J. Biol. Chem, abstract) reported on the flow cytometric analysis of intracellular L. major after labeling with polyclonal serum. Their experiments showed incomplete discrimination between infected and noninfected populations. In 1998, Abdullah et al. (1, 2) developed a method based on the staining of promastigotes with vital fluorescent dyes such as PKH-26 (9) or SYTO-17 before macrophage infection; this technique permitted accurate study of cell infection but could not detect intracellular amastigotes after prolonged incubation periods. Recently, new experiments demonstrated that accurate detection of intracellular amastigotes could be obtained after labeling with monoclonal antibodies (14); however, the availability of the method for antileishmanial drug discovery has not been investigated.

In the present study, we evaluated the possibility of using flow cytometry as a simple and reliable tool for the rapid testing of potential antileishmanial drugs. For this purpose, we used an adapted version of the method described by Goullin et al. (J. Biol. Chem, abstract). Amastigotes were labeled with monoclonal antibodies after fixation with paraformaldehyde and permeabilization with fresh ethanol.

The results demonstrated that flow cytometry could accurately quantify Leishmania infection in human monocyte-derived macrophages as well as nonadherent mouse peritoneal macrophages. They agreed with previously published data, in which labeling of intracellular amastigotes with monoclonal antibodies permitted separation of amastigote-containing cells from noninfected cells (2, 14).

As seen in Fig. 1, infected and noninfected cells separated into two well-isolated populations, permitting quantitative estimation of infection rates and indicating that fixation-permeabilization and immunofluorescence techniques provided a satisfactory means of discrimination of macrophage subpopulations, with the advantage that samples could be stored in fresh ethanol until labeling. Amastigotes were recognized by an anti-Leishmania LPG-specific monoclonal antibody, a monoclonal antibody specific for the surface-disposed repeated carbohydrate epitope of most Leishmania LPG species. LPG constitutes an important class of glycosylated phosphatidylinositols shown to be expressed at a high copy number by the promastigote stage of all Leishmania species (6). In the amastigote stage of the parasite, on the contrary, the number of LPG copies has been shown to decrease since LPG was not required for amastigote survival in the mammalian host (12). Moreover, Turco and Sacks (25) demonstrated in 1991 that L. major amastigotes could express an LPG structurally distinct from its promastigote counterpart. According to our results, identification of Leishmania amastigotes by an LPG-specific antibody was efficient with the early and late stages of the amastigote forms, since detection of intracellular parasites could be performed for 7 days after infection. This result indicated that possible LPG modifications throughout the parasite life cycle did not affect labeling. They agreed with the findings of Moody et al. (17), which showed that the results obtained from immunological studies with LPG-directed antibodies were consistent with those obtained with LPG from the amastigote stage. Moreover, our results confirmed the presence of LPG in various Leishmania species since detection of intracellular L. donovani and L. mexicana could be performed.

Sorting of fluorescent cells attested that more than 90% of the positive and negative results determined by flow cytometry could be verified by fluorescence microscopy, and comparison with conventional analysis with nonadherent macrophages established a significant correlation between the results of flow cytometry and microscopy, with the advantage that the large number of cells analyzed contributed to ensuring the good reproducibility of the cytometric technique. On the basis of these results, flow cytometric detection of intracellular amastigotes after permeabilization with ethanol and labeling with monoclonal antibodies could favorably replace conventional microscopic analysis of macrophages, which is seriously limited by the time required to obtain results. This statement was confirmed by assessment of the antileishmanial activities of four conventional antileishmanial drugs used for the treatment of clinical leishmaniasis (15) (meglumine antimoniate, pentamidine, amphotericin B, and allopurinol). As expected, the drugs induced dose-dependent decreases in infection rates compared to those for the control cultures, allowing nonlinear regression analyses for IC50 estimates. The results indicated that the antiproliferative activities exerted by conventional antileishmanial drugs on intracellular amastigotes did not depend either on the host-cell model or on the technique used to measure infection rates since no significant differences in IC50s could be detected after microscopic or cytometric analyses with human and mouse peritoneal macrophages. Nevertheless, infection rates for human adherent macrophages were higher than those observed for nonadherent cells, suggesting that differences in cell membrane capacities could modulate parasite phagocytosis.

In conclusion, the flow cytometric technique developed in the present study was shown to measure infection rates in Leishmania-infected macrophages with high degrees of specificity and reproducibility and appeared to provide accurate dose-response curves for drug testing. On the basis of the results, although its sensitivity did not allow estimates of parasite density in each cell to be obtained, flow cytometric detection of intracellular amastigotes constituted a reliable tool for the rapid assessment of antileishmanial activities and could be proposed as a means of screening the antileishmanial activities of new molecules and combinations of drugs. These promising findings could be completed by further investigations to increase the sensitivity of the technique: better analysis of fluorescence peaks, successive cell sorting, or addition of a second specific fluorescent probe. On the other hand, experiments could be performed to investigate the possibility of applying this technique to the diagnostics of leishmaniasis and susceptibility testing in clinical trials.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdullah S M, Flath B, Presber W. Comparison of different staining procedures for the flow cytometric analysis of U-937 cells infected with different leishmania species. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;37:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdullah S M, Flath B, Presber W. Mixed infection of human U-937 cells by two different species of leishmania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:182–188. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoine J C, Prina E, Lang T, Courret N. The biogenesis and properties of the parasitophorus vacuoles that harbour Leishmania in murine macrophages. Trends Microbiol. 1998;7:392–401. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman J D, Lee L S. Activity of antileishmanial agents against amastigotes in human monocyte-derived macrophages and in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Parasitol. 1984;70:220–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertho A L, Cysne L, Coutinho S G. Flow cytometry in the study of the interaction between murine macrophages and the protozoan parasite Leishmania amazonensis. J Parasitol. 1992;78:666–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogdan C, Rollinghoff M. How do protozoan parasites survive inside macrophages. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:22–28. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(98)01362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson R N. Visceral leishmaniasis in clinical practice. J Infect. 1999;39:112–116. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(99)90001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faraut-Gambarelli F, Piarroux R, Deniau M, Giusiano B, Marty P, Michel G, Faugère B, Dumon H. In vitro and in vivo resistance of Leishmania infantum to meglumine antimoniate: a study of 37 strains collected from patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:827–830. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford J W, Welling T H, Stanley J C, Messina L M. PKH26 and 1251-PKH95: characterization and efficacy as labels for in vitro and in vivo endothelial cell localization and tracking. J Surg Res. 1996;62:23–28. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouchet P, Jayat C, Hechard Y, Ratinaud M H, Frelat G. Recent advances of flow cytometry in fundamental and applied microbiology. Biol Cell. 1993;78:95–109. doi: 10.1016/0248-4900(93)90120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gay-Andrieu F, Cozon G J, Ferrandiz J, Kahi S, Peyron F. Flow cytometric quantification of Toxoplasma gondii cellular infection and replication. J Parasitol. 1999;85:545–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser T A, Moody S F, Handman E, Bacic A, Spithill T W. An antigenically distinct lipophosphoglycan on amastigotes of Leishmania major. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;45:337–344. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90102-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grogl M, Thomason T N, Franke E D. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis: its implication in systemic chemotherapy of cutaneaous and mucocutaneous disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:117–126. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guinet F, Louise A, Jouin H, Antoine J C, Roth C W. Accurate quantitation of Leishmania infection in cultured cells by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 2000;39:235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herwalt B L. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1999;354:1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Looker D L, Martinez S, Horton J M, Marr J J. Growth of Leishmania donovani amastigotes in the continuous cell line U937: studies of drug efficacy and metabolism. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:323–327. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moody S F, Handman E, McConville M J, Bacic A. The structure of Leishmania major amastigote lipohposphoglycan. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18457–18466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moss D M, Croppe G P, Wallace S, Visvesvara G S. Flow cytometric analysis of microsporidia belonging to the genus Encephalitozoon. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:371–375. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.371-375.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann N F, Gyurek L L, Gammie L, Finch G R, Belosevic M. Comparison of animal infectivity and nucleic acid staining for assessment of Cryptosporidium parvum viability in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:406–412. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.1.406-412.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogunkolade B W, Colomb-Valet I, Monjour L, Rhodes-Feuillette A, Abita J P, Frommel D. Interactions between the human monocytic leukaemia THP1 cell line and Old and New World species of Leishmania. Acta Trop. 1990;47:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(90)90023-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onah D N, Hopkins J, Luckins A G. Changes in peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations and parasite-specific antibody responses in Trypanosoma evansi infection of sheep. Parasitol Res. 1999;85:263–269. doi: 10.1007/s004360050545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piper K P, Roberts D J, Day K P. Plasmodium falciparum: analysis of the antibody specificity to the surface of the trophozoite-infected erythrocyte. Exp Parasitol. 1999;91:161–169. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sereno D, Holzmuller P, Lemesre J L. Efficacy of second line drugs on antimonyl-resistant amastigotes of Leishmania infantum. Acta Trop. 2000;74:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(99)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staalsoe T, Giha H A, Dodoo D, Theander T G, Hviid L. Detection of antibodies to variant antigens on Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1999;35:329–336. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19990401)35:4<329::aid-cyto5>3.3.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turco S J, Sacks D L. Expression of a stage-specific lipophosphoglycan in Leishmania major amastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;45:91–99. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90030-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veras P S, Moulia C, Dauguet C, Tunis C T, Thibon M, Rabinovitch M. Entry and survival of leishmania amazonenesis amastigotes within phagolysosome-like vacuoles that shelter Coxiella burnetti in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3505–3506. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3502-3506.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]