Significance

Huashi Baidu decoction (Q-14), a famous traditional Chinese medicine decoction for COVID-19, has good effects on SARS-CoV-2 RNA clearance, promoting lung lesion opacity absorption, reducing inflammation, and ameliorating flu-like symptoms based on a series of clinical trials, having potent antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects. However, due to the lack of systematic and in-depth research, little significant progress has been made in the study of TCMT-NDRD of HBF for COVID-19 management. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to identify key antiviral and anti-inflammatory bioactive compounds from HBF based on an integrative pharmacological strategy. These findings will greatly stimulate the traditional Chinese medicine theory-driven natural drug discovery against COVID-19 and promote the modern research of Chinese medicine.

Keywords: COVID-19, traditional Chinese medicine, TCMT-NDRD, antivirus, anti-inflammation

Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is an ongoing global health concern, and effective antiviral reagents are urgently needed. Traditional Chinese medicine theory-driven natural drug research and development (TCMT-NDRD) is a feasible method to address this issue as the traditional Chinese medicine formulae have been shown effective in the treatment of COVID-19. Huashi Baidu decoction (Q-14) is a clinically approved formula for COVID-19 therapy with antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects. Here, an integrative pharmacological strategy was applied to identify the antiviral and anti-inflammatory bioactive compounds from Q-14. Overall, a total of 343 chemical compounds were initially characterized, and 60 prototype compounds in Q-14 were subsequently traced in plasma using ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Among the 60 compounds, six compounds (magnolol, glycyrrhisoflavone, licoisoflavone A, emodin, echinatin, and quercetin) were identified showing a dose-dependent inhibition effect on the SARS-CoV-2 infection, including two inhibitors (echinatin and quercetin) of the main protease (Mpro), as well as two inhibitors (glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A) of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). Meanwhile, three anti-inflammatory components, including licochalcone B, echinatin, and glycyrrhisoflavone, were identified in a SARS-CoV-2-infected inflammatory cell model. In addition, glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A also displayed strong inhibitory activities against cAMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4). Crystal structures of PDE4 in complex with glycyrrhisoflavone or licoisoflavone A were determined at resolutions of 1.54 Å and 1.65 Å, respectively, and both compounds bind in the active site of PDE4 with similar interactions. These findings will greatly stimulate the study of TCMT-NDRD against COVID-19.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is a highly contagious enveloped positive-strand RNA virus that causes respiratory diseases, fever, and severe pneumonia in humans (1–3). Currently, anti-COVID-19 drugs are under development and have achieved significant success, including remdesivir and molnupiravir (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitors) (4–6), Paxlovid and Xocova (ensitrelvir) [inhibitors of the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 (SARS-CoV-2 Mpro)] (7), and tocilizumab (an interleukin (IL)-6 receptor inhibitor) (8). As SARS-CoV-2 is characterized by high mutation and recombination rates (9), more effective antiviral drugs are urgently needed. In this scenario, combination therapies that act on multiple targets remain an indispensable direction for the research and development of anti-COVID-19 drugs (10, 11).

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory-driven natural drug research and development (TCMT-NDRD) is highlighted by the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Youyou Tu for the discovery of artemisinin in the treatment of malaria (12, 13). Since the outbreak of COVID-19 (2, 14), research and development of TCM formulae (TCMFs) have been strongly supported in China. TCMFs have been widely used as preventive therapies against COVID-19 because they were approved by the National Medical Products Administration of China (NMPA), such as Huashi Baidu decoction (Q-14) (15, 16), Qingfei Paidu decoction (17), and Xuanfei Baidu decoction (18). It is believed that the combination of antivirus and anti-inflammation effects is the main pharmacological result of the TCMFs used for the treatment of COVID-19 (19, 20). Notably, a few antiviral and anti-inflammatory compounds have been discovered from the TCMFs, such as leupeptin (Mpro inhibitor) from Qing-Fei-Pai-Du decoction (21), baicalein (Mpro inhibitor) from Shuang-Huang-Lian oral liquid (22), and paeoniflorin (the regulator of IL-6) from Xuebijing injection (23).

Q-14, a well-known TCMF for COVID-19, has been developed into granules (Q-14) that was approved by the NMPA in 2021, consists of 14 Chinese herbs: the sovereign herbs Ephedrae Herba (Mahuang, MH), Pogostemonis Herba (GuangHuoxiang, GHX), and Gypsum Fibrosum (Shigao, SG); ministerial herbs—Armeniacae Semen Amarum (Kuxingren, KXR), Pinelliae Rhizoma (Banxia, BX), Magnoliae Officinalis Cortex (Houpo, HP), Atractylodis Rhizoma (Cangzhu, CZ), Tsaoko Fructus (Caoguo, CG), and Poria (Fuling, FL); the adjuvant herbs Astragali Radix (Huangqi, HQ), Descurainiae Semen (Nantinglizi, TLZ), Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao, CS), and Rhei Radix et Rhizoma (Dahuang, DH); and the messenger herb Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (Gancao, GC) (15). Several clinical trials have revealed that Q-14 has better effects on SARS-CoV-2 RNA clearance, promoting lung lesion opacity absorption, reducing inflammation, and ameliorating flu-like symptoms (e.g., sore throat and chest pain), which suggests that Q-14 may have potent antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects (15, 16, 24, 25). In previous studies, 217 constituents in Q-14 have been preliminarily identified (26), and some potential bioactive constituents (e.g., quercetin, luteolin, kaempferol, emodin, and rhein) are hypothesized to have antiviral and anti-inflammatory properties based on computational biology and network pharmacology (27–29). However, due to the lack of systematic and in-depth research, little progress has been made in the study of TCMT-NDRD of Q-14 for COVID-19 management. To address this, we applied an integrative pharmacological strategy to identify key antiviral and anti-inflammatory bioactive compounds by the integration of the high-throughput UPLC-Q-TOF/MS method, the systematic evaluation of the antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities of the components, and further molecular and structural studies. These findings will greatly promote the development of natural drugs for the treatment of COVID-19.

Results

Q-14 Decreases SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load and Alleviates Pulmonary Inflammation In Vivo.

The SARS-CoV-2-infected human ACE2 (hACE2) transgenic mice had been established in our previous studies (30, 31), which were used to investigate the antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects of Q-14 against COVID-19. The average weight loss rates of the model control and treatment groups 5 d postinfection (dpi) were 4.86% and 4.17%, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). The median viral load of lung tissue in the model control group was 106.84 copies/mL, which was slightly decreased after the treatment of Q-14 (106.42 copies/mL; SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). The expression of inflammatory cytokines such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), monoclonal immunoglobulin (MIG), C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (IP-10/CXCL-10), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-6, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), IL-10, and IL-1α was significantly reduced with Q-14 treatment (all ps < 0.05), while IL-17A and IL12p70 did not show an obvious difference between the model control and treatment groups (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). In terms of pathological changes in the lungs, the model control group displayed moderate interstitial pneumonia, while the Q-14 treatment obviously ameliorated the lung inflammation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D).

Characterization of the Chemical Compound Profile of Q-14.

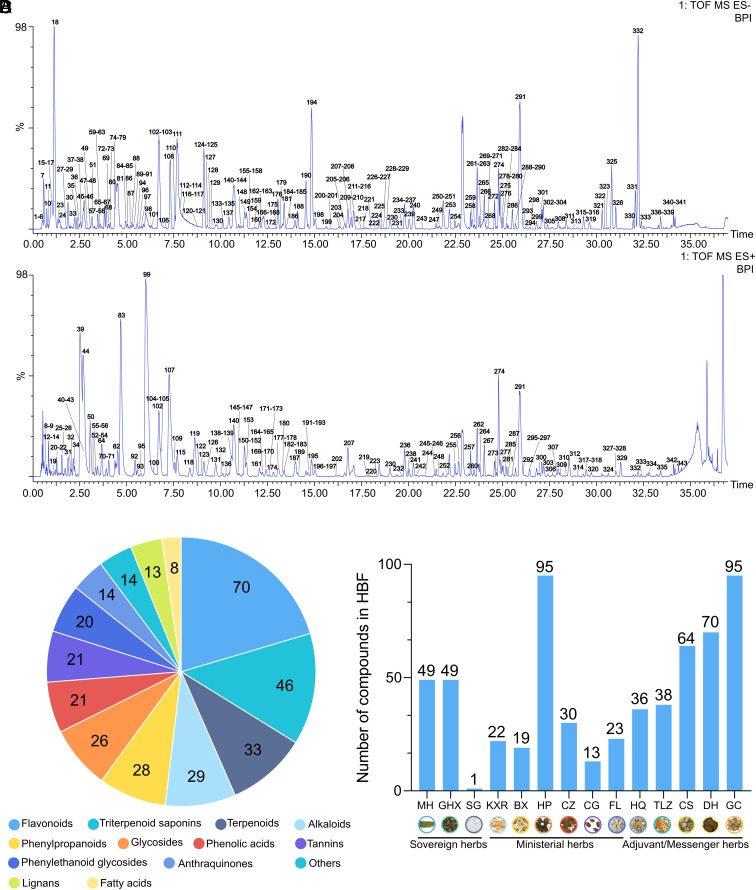

As a very complex prescription, the accurate and high-throughput characterization of the chemical compounds in Q-14 is a prerequisite for TCMT-NDRD. Ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF/MS) was used for the identification of the chemical components of Q-14. As shown in Fig. 1 A and B, the chemical base peak ion (BPI) chromatogram of Q-14 was classified into two categories based on the negative and positive ion modes of UPLC-Q-TOF/MS. To achieve high-throughput identification of chemical compounds, the UNIFI screening platform was utilized to process and analyze the MS data. We then automatically matched the fragment information with an Q-14 library of chemical compounds in the encyclopedia of traditional Chinese medicine (ETCM) databases (32). After further manual verification, 68 standards (Dataset S1) were used to characterize the fragmentation patterns and increase the reliability of compound identification. Overall, a total of 343 chemical compounds, including 70 flavonoids, 46 triterpenoid saponins, 33 terpenoids, 29 alkaloids, 28 phenylpropanoids, 26 glycosides, 21 phenolic acids, 21 tannins, 20 phenylethanoid glycosides, 14 anthraquinones, 13 lignans, 8 fatty acids, and 14 others in Q-14, were identified or tentatively characterized with retention times (RTs) and fragmentation patterns (Fig. 1C). The herbs and the number of their components are further summarized in Fig. 1D (MH 49, GHX 49, KXR 22, BX 19, HP 95, CZ 30, CG 13, FL 23, HQ 36, TLZ 38, CS 64, DH 70, and GC 95). It is noteworthy that some compounds were simultaneously identified in several herbs, such as quercetin in DH, TLZ, GC, CG, MH, and CS. However, CaSO4·2H2O contained in SG, a mineral herb, was not identified by mass spectrometry. Detailed information on RT, adducts, m/z (mass-to-charge ratio), mass error, formula, fragment ions, identification, structure type, and the source of the HBF chemical compounds is listed in Dataset S1.

Fig. 1.

Chemical identification of Huashi Baidu decoction (Q-14) using ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF/MS). (A) The chemical base peak ion (BPI) chromatogram of Q-14 in the negative ion mode. (B) The BPI chromatogram of Q-14 in the positive ion mode. (C) Structural classification of compounds contained in Q-14. (D) The number of chemical components for each herb.

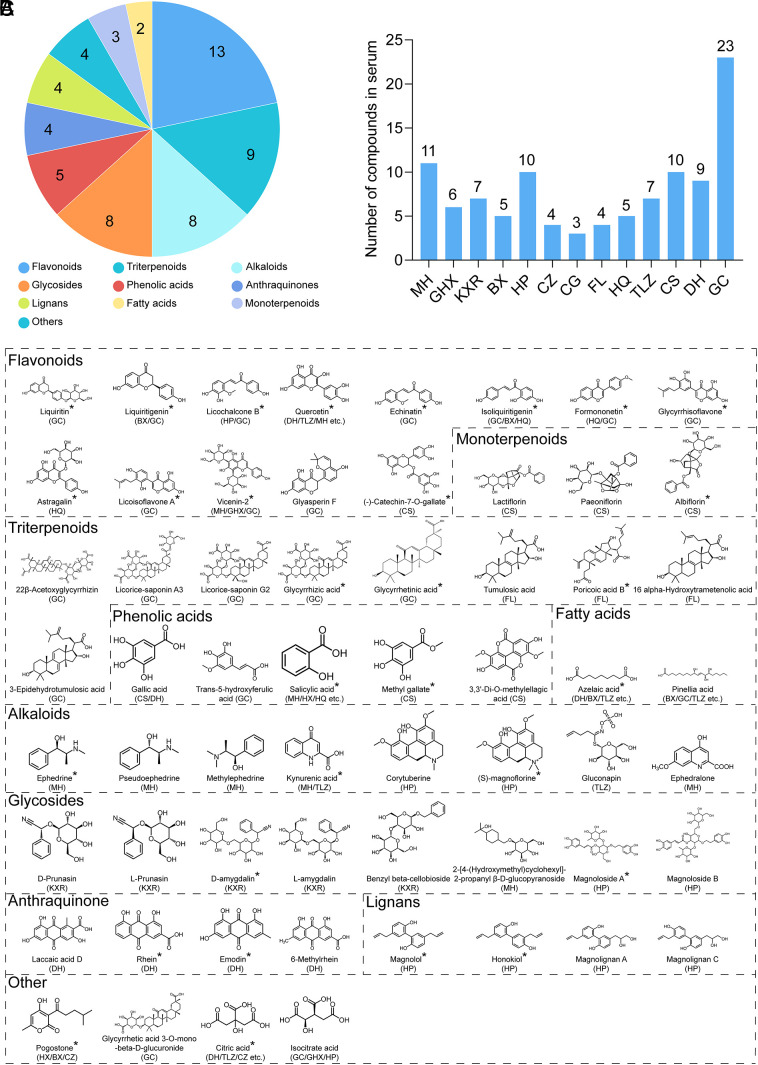

Moreover, the prototype compounds (referred to chemical components that were observed in both Q14 and plasma) of Q-14 in vivo were traced for TCMT-NDRD to determine the potential bioactive compounds against COVID-19. The prototype compounds in plasma were characterized after intragastric administration of Q-14 using the UPLC-Q-TOF-MS system (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Sixty prototype compounds were found, including thirteen flavonoids, nine triterpenoid saponins, eight alkaloids, eight glycosides, five phenolic acids, four anthraquinones, three terpenoids, four lignans, two fatty acids, and four others (Fig. 2A). The herbs and the number of components are summarized in Fig. 2B (MH 11, GHX 6, KXR 7, BX 5, HP 10, CZ 4, CG 3, FL 4, HQ 5, TLZ 7, CS 10, DH 9, and GC 23), and the structures of the prototype compounds are shown in Fig. 2C. Notably, 30 prototype compounds are commercially available for subsequent experiments on antivirus and anti-inflammation screening (matched articles are marked with an asterisk in Fig. 2C). Detailed information on RT, adducts, m/z (mass-to-charge ratio), mass error, formula, fragment ions, identification, structure type, and the source of the 60 compounds with prototype structures is listed in Dataset S2.

Fig. 2.

The compounds with prototype structures in plasma after Q-14 treatment using the UPLC-Q-TOF/MS system. (A) Structural classification of prototype compounds in plasma. (B) The number of prototype compounds in plasma for each herb. (C) Structures of the prototype compounds in plasma.

Screening of Antiviral Compounds from Q-14.

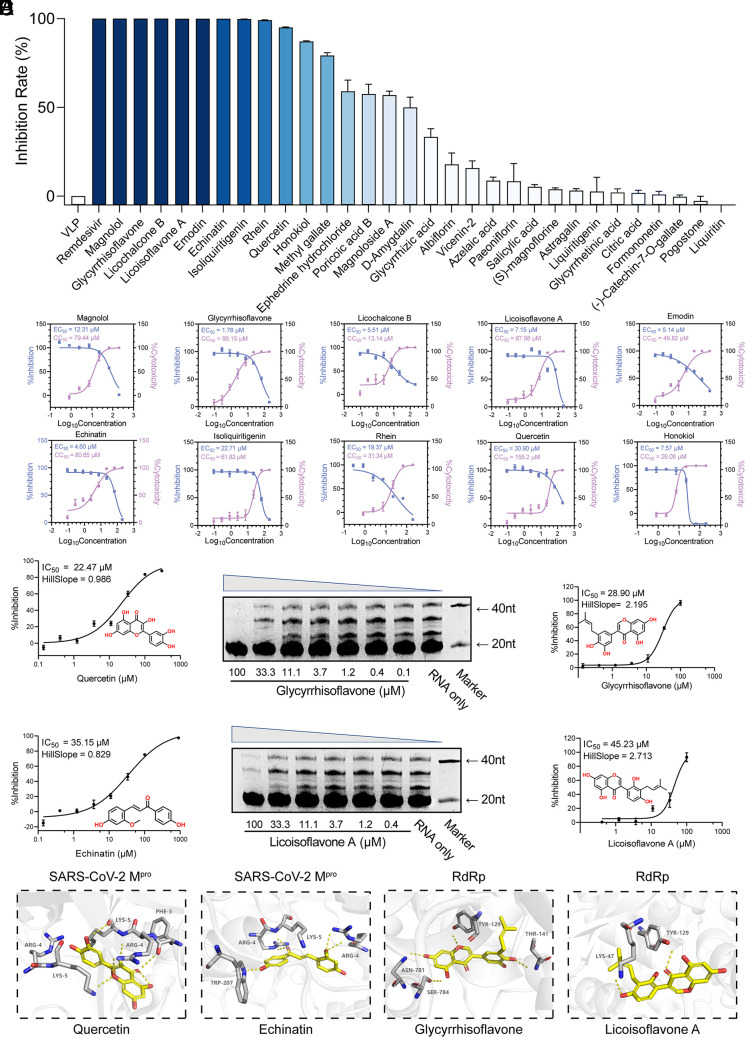

To screen the bioactive compounds from Q-14 that possess antiviral effects, a packaging cell line for ectopic expression of the nucleocapsid (Caco-2-N) infected with SARS-CoV-2-like particles (trVLPs) was conducted, which is a safe and convenient method to produce trVLPs in biosafety level (BSL)-2 laboratories (33). We found that 10 compounds (magnolol, glycyrrhisoflavone, licochalcone B, licoisoflavone A, emodin, echinatin, isoliquiritigenin, rhein, quercetin, and honokiol) possess remarkable antiviral activities, with inhibition rates >90% at 100 μM concentration (Fig. 3A). Given the encouraging results from the primary screening, we then characterized the 50% effective concentration (EC50) and 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values for the top 10 compounds (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the selectivity index (SI) was calculated as the ratio of the CC50 to the antiviral EC50 (CC50/EC50), a measure for the therapeutic window of the compound in the assay system. Six compounds with SI > 5.0, including magnolol, glycyrrhisoflavone, licoisoflavone A, emodin, echinatin, and quercetin (Fig. 3B), possess a relatively large therapeutic window and good druggability.

Fig. 3.

Screening of antiviral compounds from Q-14. (A) Preliminary screening of commercially available prototype compounds with antiviral activity at 100 μM based on a packaging cell line for ectopic expression of the nucleocapsid (Caco-2-N) infected with SARS-CoV-2-like-particles (trVLPs). (B) The 50% effective concentration (EC50) and 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values of the top 10 compounds. The antiviral activity (blue) and cytotoxicity (violet) were measured. (C) SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibition activities of quercetin and echinatin by a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)–based protease assay. (D) The inhibition of RdRp by glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A measured using an in vitro polymerase activity assay. (E) Molecular docking of quercetin and echinatin on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A on RdRp. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and RdRp are shown in gray cartoon representation, essential residues in gray sticks, and four compounds (quercetin, echinatin, glycyrrhisoflavone, and licoisoflavone A) in yellow sticks. The polar interactions between the compounds and SARS-CoV-2 Mpro/RdRp are shown in yellow dashes. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Experiments were repeated in triplicate, independently.

Considering their crucial roles in viral replication and infection, SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and RdRp are attractive targets for antiviral drugs. Thus, we evaluated the six compounds with high SI by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)–based protease and in vitro polymerase activity assays, and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was calculated from dose–response curves (Fig. 3 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). As shown in Fig. 3C, quercetin and echinatin displayed moderate SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibition activities at submicromolar levels, with IC50 values of 35.14 and 22.47 μM, respectively. Moreover, glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A exhibited significant inhibitions against RdRp, with IC50 values of 28.90 and 47.31 μM, respectively (Fig. 3D).

Molecular docking was further utilized to estimate the binding interactions between the compounds and target proteins. We docked quercetin and echinatin on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A on RdRp (34) (Fig. 3E). The binding energy values of quercetin, echinatin, glycyrrhisoflavone, and licoisoflavone A were −9.01, −7.78, −9.20, and −9.01 kcal/mol, respectively. Quercetin and echinatin are predicted to form hydrogen bonds with Arg4 and Lys5 of Mpro (Fig. 3E). In addition, glycyrrhisoflavone is predicted to form hydrogen bonds with Asn781, Ser784, and Thr141 (Fig. 3E), and licoisoflavone A may form hydrogen bonds with Tyr129 and Lys47 (Fig. 3E). Although with great efforts, regrettably, we could not get any complex structures, which is the limitation of this study and should be explored in the future.

Screening of Anti-Inflammatory Compounds from Q-14.

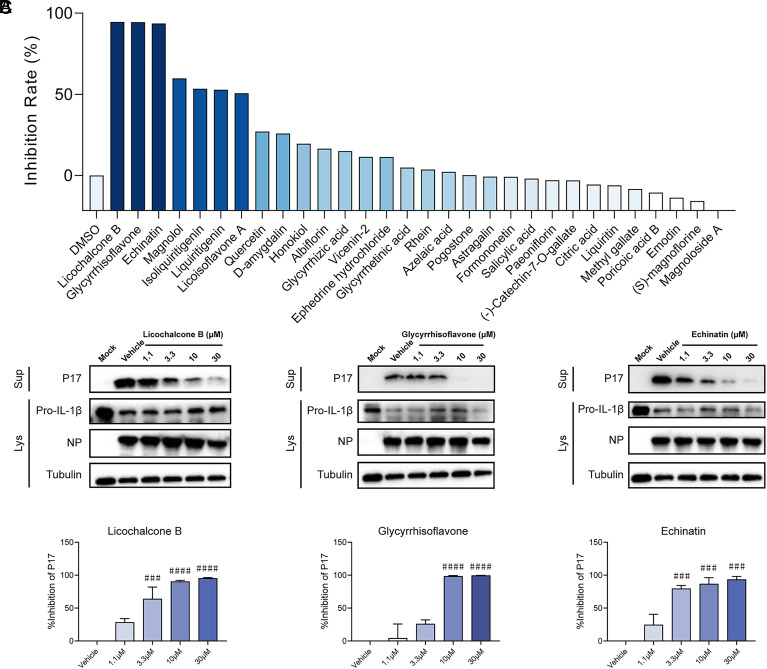

Reducing uncontrolled inflammation is a therapeutic strategy for severe COVID-19 with exaggerated immune responses demonstrated by overproduction of proinflammatory mediators (cytokine storm). Similar to SARS-CoV-2, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) infection can lead to a cytokine storm in critically ill patients with increased production and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, etc.) (35–37). SFTSV-infected THP-1 macrophage is an established inflammatory cell model to assess virus-triggered inflammation through detecting the production and secretion of IL-1β (38, 39). The anti-inflammatory activity of the compounds from Q-14 was further evaluated on an inflammatory cell model based on infection by SFTSV. Preliminary screening of the anti-inflammatory activity of 30 compounds in Q-14 was conducted on SFTSV-infected THP-1 macrophage at a concentration of 10 μM. Among the 30 compounds, licochalcone B, glycyrrhisoflavone, and echinatin demonstrated the most robust anti-inflammation activities (inhibition rate > 90%), as evaluated by the secretion of the matured form of IL-1β (P17) (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). To validate the anti-inflammation activity of these three compounds, THP-1 macrophages infected with SFTSV (MOI = 5) were treated with each compound at concentrations of 1.1, 3.3, and 10 μM. Forty-eight hours postinfection, the inhibition rates of P17 secretion were analyzed as described above. All three compounds displayed anti-inflammation activity in a dose-dependent manner (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 B and C). The inhibition effect of these three compounds against SARS-CoV-2-triggered inflammation was further evaluated on an established SARS-CoV-2-infected inflammatory cell model (40). Calu-3 cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 and treated with each compound at a series of indicated concentrations. The results indicated that all three compounds reduced SARS-CoV-2-induced IL-1β P17 release in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4 B and C).

Fig. 4.

Screening of anti-inflammatory compounds from Q-14. (A) Preliminary screening of the anti-inflammatory activity of 30 compounds from Q-14. THP-1 macrophages were incubated with SFTSV (MOI = 5) for 1 h and treated with the 30 compounds in Q-14 at a concentration of 10 μM. Cells and supernatants were harvested 48 h postinfection. P17 levels in supernatants and the expression levels of Pro-IL-1β or NP in cell lysates were determined by western blotting. The inhibition rates were evaluated by analysis of gray values of the P17 bands. (B and C) The anti-inflammatory activity of licochalcone B, glycyrrhisoflavone, and echinatin on the release of P17 induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Calu-3 cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI = 0.1) in the presence of licochalcone B, glycyrrhisoflavone, and echinatin at concentrations of 1.1, 3.3, 10, or 30 μM. Cells and supernatants were collected 48 h postinfection. P17 levels in supernatants and expression levels of Pro-IL-1β or NP in cell lysates were determined by western blotting (B). The inhibition rates were evaluated by analysis of gray values of the P17 bands (C). Data are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ###P < 0.001; ####P < 0.0001.

Bioactive Compounds from Q-14 Targeting PDE4.

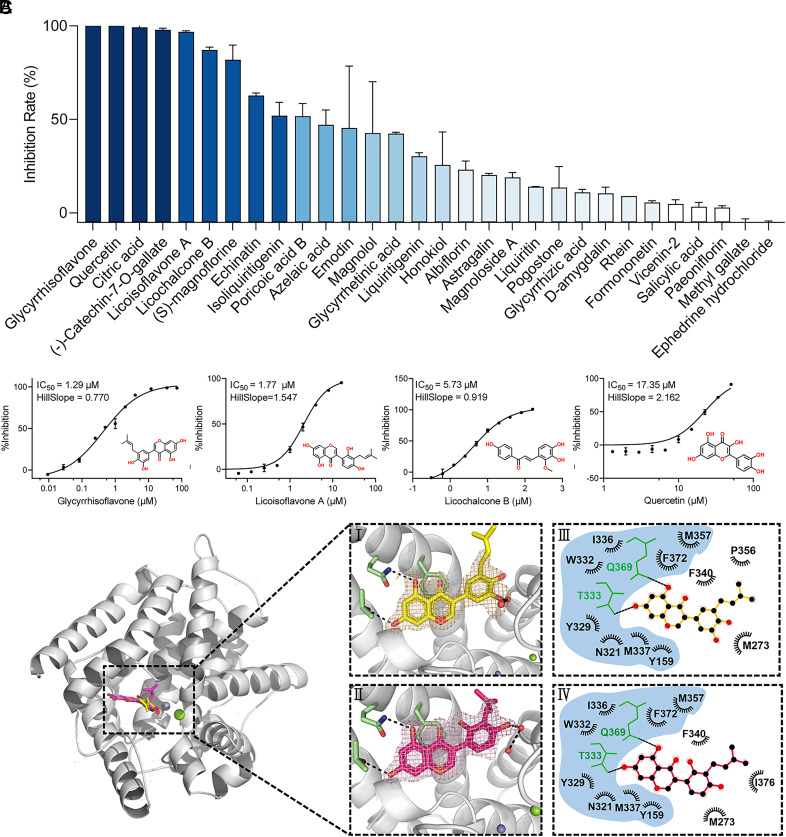

Phosphodiesterase type 4 (PDE4) is suggested to be crucial for the activation of neutrophils and neutrophil-mediated inflammatory responses during the progression of COVID-19 (41); a total of 30 prototype compounds in Q-14 were screened for their ability to target PDE4 using a scintillation proximity assay (SPA). The primary screening led to the discovery of ten compounds that inhibit more than 50% of the activity of PDE4 at 50 μM concentration (Fig. 5A). Regrettably, both (-)-catechin-7-O-gallate and poricoic acid B were excluded because of their own limitations. The challenge in obtaining an effective IC50 curve for poricoic acid B can be attributed to its poor solubility, which can significantly impede its bioavailability. (-)-catechin-7-O-gallate is structurally almost identical to epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), except for the lack of a hydroxyl group. Due to its indiscriminate potent activity against multiple targets, EGCG has also been considered a potential pan-assay interference compound (PAINS), which refers to small-molecule compounds that exhibit pharmacological activity, such as selective inhibition or activation of targets, across a range of assay systems but indeed displays indiscriminate reactivity. In practice, these compounds display nonspecific reactivity, which can interfere with multiple biological targets and lead to misleading results (42, 43). Further screening experiments were performed to confirm that four compounds, glycyrrhisoflavone, quercetin, licoisoflavone A, and licochalcone B, showed the best inhibition effects toward PDE4 at 5 μM (Dataset S3). The IC50 values of the four active compounds were determined as 1.29, 17.35, 1.77, and 5.73 μM (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of PDE4 by the compounds from Q-14. (A) Preliminary screening of enzymatic inhibition by 30 compounds from Q-14 at 50 μM using the scintillation proximity assay (SPA). (B) The representative IC50 curves of PDE4 inhibition by glycyrrhisoflavone, quercetin, licoisoflavone A, and licochalcone B. The curves were obtained by fitting a four-parameter logistic model to the data points, which represent the mean of single independent experiments. (C) Overview of the structures of glycyrrhisoflavone- and licoisoflavone A–bound PDE4 (PBD codes 7YQF and 7YSX). The protein is shown in cartoon representation. Glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A are shown as yellow and magenta sticks, respectively. (I-II) Interactions formed between glycyrrhisoflavone (yellow) or licoisoflavone A (magenta) and surrounding residues (green). Residues and the ligand are shown as sticks, and hydrogen bonds are represented by black dashed lines. 2Fo-Fc electron density maps (yellow and magenta) were contoured at 1.0 σ. (III-IV) Ligplots of all residues making either hydrophobic or hydrogen-bonding interactions with glycyrrhisoflavone (yellow) or licoisoflavone A (magenta). IC50 values were shown as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

To reveal the binding mode of these four compounds to PDE4, they were soaked into crystals of the PDE4 catalytic domain. This allowed us to solve the crystal structures of PDE4 in complex with glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A at resolutions of 1.54 and 1.65 Å, respectively (Fig. 5C and Dataset S4). We found that both compounds occupied the PDE4 active site with a similar binding mode. Examination of the detailed interactions revealed that two phenolic hydroxyl groups of the chromone in both glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A formed two hydrogen bonds with the side chains of the conserved residues Q369 and T333 (Fig. 5C). In addition, a hydroxyl group in the free benzene ring of glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A formed a hydrogen bond with adjacent water molecules. Aside from hydrogen bond interactions, the two compounds formed extensive hydrophobic interactions with residues N321, Y329, F372, I336, W332, M337, Y159, and M357 (Fig. 5C). These results together provide the molecular mechanism underlying the recognition of glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A by PDE4 and a structure-based interpretation for the potent inhibitory activity against PDE4.

Discussion

A large number of TCMFs against epidemic diseases have been accumulated according to the guidance of TCM theories and clinical empirical knowledge in the past thousands of years. Based on the ancient well-known TCMFs, various TCMFs have quickly developed for the treatment of COVID-19, including the three popularly used formulae and three medicines: Jinhua Qinggan granule, Lianhua Qingwen granule, Xuebijing injection, Qingfei Paidu decoction, Xuanfei Baidu decoction, and Q-14 (21, 44–47). However, the key bioactive substances and functional mechanisms of the TCMFs are yet elusive, which has restricted the global acceptance of TCMs. Therefore, TCMT-NDRD is an effective strategy that will be helpful to promote the discovery of natural drugs and the modern research of TCM. Herein, an integrative pharmacological strategy was used to identify the main antiviral and anti-inflammatory bioactive compounds from a clinically effective prescription, Q-14. A total of 343 chemical compounds from Q-14 were initially characterized, of which 60 prototype compounds were traced in vivo using the UPLC-Q-TOF-MS system. Among these compounds in plasma, we identified six compounds (magnolol, glycyrrhisoflavone, licoisoflavone A, emodin, echinatin, and quercetin) as a dose-dependent inhibition effect on SARS-CoV-2 infection, including SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors (echinatin and quercetin) and RdRp inhibitors (glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A). Meanwhile, three components (licochalcone B, echinatin, and glycyrrhisoflavone) were screened out and validated to have dose-dependent effects on reducing SARS-CoV-2-induced IL-1β P17 release in the inflammatory cell model.

PDE4, a member of the PDE superfamily, is an important hydrolase of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). PDE4 regulates cAMP-related signaling pathways and is associated with physiological and pathological responses, including neutrophil infiltration, monocyte and macrophage activation, and myocardial contractility (48, 49). Interestingly, we also found that glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A inhibit the catalytic activity of PDE4, suggesting that these two compounds have dual antiviral and anti-inflammatory functions. Considering the complex pathophysiology of COVID-19, therapeutic strategies should include combating viral infections, regulation of the “immune inflammation” system, and preventing lung fibrosis and injury (46). Therefore, the dual-functional compounds found in our study, glycyrrhisoflavone and licoisoflavone A, will be promising drug candidates for the treatment of COVID-19. Due to the scarcity of BSL-3 facilities, we did not perform the in vivo experiments to study the effect and safety of the lead compounds at this stage, which will be accomplished in the future study.

It is critical to explore the interactions between TCM components and disease targets for the modernization of TCM (50). In our studies, six compounds of Q-14 showed notable anti-SARS-CoV-2 effect and five compounds of Q-14 had obvious inhibitory effect on inflammatory response. Among them, four compounds (echinatin, glycyrrhisoflavone, licoisoflavone A, and quercetin) were exhibiting both anti-SARS-CoV-2 and anti-inflammatory activities. These results suggested that synergistic effect of multicomponents and multitargets might be the reason for TCMFs to exert clinical efficacy. In addition to the compounds with prototype structures, 67 metabolites of Q-14 in plasma were identified using the UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS system (Dataset S2), which may also be important contributors to the therapeutic or toxic effects. An integrative bioinformatic analysis of multiomics data, clinical symptom-related genes, and target prediction of the bioactive compounds demonstrated that the underlying mechanisms of Q-14 against COVID-19 appear much more complex, which will refer to antiviral effects, the regulation of the “immune inflammation” system, angiogenesis and platelet activation, and energy metabolism (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Otherwise, the intestinal microbiome and drug-metabolizing enzymes may also be targets for TCM formulae (51).

In conclusion, we identified the bioactive compounds from Q-14 that possess antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities by inhibiting viral replication and inflammation and provided candidate compounds for the development of anti-COVID-19 drugs. Our study sheds light on the TCMT-NDRD and promotes the modern research of TCM.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement.

SD rats for prototype compound identification were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Beijing, China, 2021B020). All SARS-CoV-2 infectious virus manipulations were conducted in a BSL-3 facility. All of the animal experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Peking Union Medical College (Beijing, China, BLL21008). All animals involved in this research were in good health. All animal handling procedures were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH and followed the guidelines of the Animal Welfare Act.

Preparation of Q-14.

According to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia 2020 Edition, Q-14 consisting of 14 Chinese herbs was purchased from Guangdong Yifang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., as described in Dataset S5. All Chinese herbs have been identified by Prof. Huasheng Peng, National Resource Center for Chinese Materia Medica, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences.

Mouse Experiments.

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) female hACE2 mice (6 to 8 wk old) were obtained from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Peking Union Medical College, which mimic a human immune system by microinjection of the mouse angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (Ace2) promoter driving the human ACE2 coding sequence into the pronuclei of fertilized ova from wild-type mice, as previously described (30, 52). Twelve hACE2 mice were randomly assigned to two groups (n = 6 per group): the model group and the HBF treatment group. Treatment group mice were orally gavaged with HBF at 11.4 mg/kg with a cycle of five consecutive days on drug, and model group mice orally inoculated with an equal volume of PBS were used as a mock infection control. After being intraperitoneally anesthetized by 2.5% avertin at 0.02 mL/g body weight, all hACE2 mice were inoculated intranasally with SARS-CoV-2 stock virus at a dosage of 105 TCID50. Daily clinical observations were conducted, and mouse body weights were recorded. Five days postinfection, mice were killed, and lung tissues were collected for following up viral load determination (by RT-qPCR), cytokine assays, and pathological examination. Specific experimental details are presented in SI Appendix, Supplement 1.

Chemical and Prototype Compounds in the Plasma Identification.

A rapid, sensitive, and reliable UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS method was performed to identify the chemical and active compound profiles of Q-14. To prepare Q-14 solution, 14 herbs were precisely weighed and boiled with 10 times of water for 2 h, followed by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 5 min. After extraction, the filtrate was collected through a 0.22-μm filter, and 1.0 μL was injected into the UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS system for analysis. To identify the compounds, we used a library of standards with both the exact mass provided by the Q-TOF detector and the RT based on the known databases ETCM (http://www.nrc.ac.cn:9090/ETCM/, version 2.0) (32), CNKI (https://www.cnki.net/), and PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Analysis was conducted on an ACQUITY UPLC-I-Class interfaced with Synapt-XS Q-TOF-MS (Waters) with an ESI. UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS conditions are provided in SI Appendix, Supplement 2~3. Moreover, the fragmentation patterns and pathways of the standards were carefully examined to further confirm the structure of their derivatives. A total of 57 reference standards (purity ≥98%) were purchased, and detailed information of the reference standards is provided in Dataset S6. Data were analyzed using UNIFI 1.8 software (Waters). Based on reference standards, chromatographic elution behaviors, chemical composition, and mass fragment patterns, chemical identifications were conducted with a mass error of <10 ppm/5 mDa.

Virus Strains and Cells.

SARS-CoV-2-trVLPs (Wuhan-Hu-1 strain, GenBank: MN908947) and the packaging cell line Caco-2-N (ATCC, catalog no.: HTB-37) were obtained from Prof. Qiang Ding (School of Medicine, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China) (33). Caco-2-N cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% FBS (GIBCO), penicillin (100 IU/mL), and streptomycin (100 lg/mL) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C and passaged every 2 to 3 d. The SARS-CoV-2 strain (SARS-CoV-2/human/CHN/Delta-2/2021, GenBank: OM061695) was provided by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, CAMS and PUMC. The SARS-CoV-2 original strain (IVCAS 6.7512) was obtained from the National Virus Resource Center and propagated in Vero E6 cells. The SFTSV strain HBMC16 obtained from China Centre for General Virus Culture Collection was propagated and titrated in Vero cells as described previously (35). THP-1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (GIBCO) containing 10% FBS (GIBCO), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate (GIBCO) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Calu-3 cells obtained from the ATCC were cultured in minimum Eagle’s medium (MEM; GIBCO) containing 1% sodium pyruvate (100 mM, Gibco), 1% MEM nonessential amino acids (GIBCO), 10% FBS (GIBCO), and antibiotics (GIBCO) in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

Protein Expression and Purification.

The SARS-CoV-2 polymerase complex consisting of the nsp12 catalytic subunit and nsp7-nsp8 cofactors, SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, and PDE4 were expressed and purified using the baculovirus and Escherichia coli (BL21, DE3) bacteria expression systems, as previously described (53–55). Detailed information on the experiments is described in SI Appendix, Supplement 4.

Antiviral Activity Assay.

Thirty commercially available compounds were tested for antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities (Dataset S7). Caco-2-N cells were used in the experiments to screen the main bioactive compounds from Q-14 exerting antiviral effects. Caco-2-N cells were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. Cells were exposed to different concentrations of drugs for 1 h and then inoculated with SARS-CoV-2-trVLPs at 1,000 TCID50. The fluorescence values were measured using a CQ1 confocal imaging quantitative cell analysis system (Yokogawa), and the inhibition rates were calculated. The EC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA).

Cell Viability Assay.

Cell viability was measured by the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, MCE, NJ, USA) assay, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, as described in SI Appendix, Supplement 5. The CC50 was calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA). The CC50 and EC50 values were used to calculate the SI (SI = CC50/EC50).

High-Throughput Mpro Inhibition Activity Assay.

A FRET assay was adopted to measure the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibition activity. Fluorescence values were determined using the CLARIOstar Plus multifunctional microplate detection system (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor baicalein (56, 57) (Shanghai yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China, purity ≥ 98%) was used as a positive control. Detailed information on this experiment is provided in SI Appendix, Supplement 6.

In Vitro Polymerase Activity Assay.

To explore the antiviral therapy targets, a series of in vitro activity assays were performed. The activity of SARS-CoV-2 polymerase complex (RdRp) was tested using in vitro primer extension experiments as described previously (53). A 40-nt template RNA (5′-CUAUCCCCAUGUGAUUUUAAUAGCUUCUUAGGAGAAUGAC-3′) corresponding to the 3′ end of the SARS-CoV-2 genome was annealed to a complementary 20-nt primer containing a 5′-carboxyfluorescein label (5′FAM-GUCAUUCUCCUAAGAAGCUA-3′). Images were taken using a Vilber Fusion system and quantified with ImageJ software. Detailed information on the protocol is described in SI Appendix, Supplement 6.

Molecular Docking.

The bioactive compounds quercetin, echinatin, glycyrrhisoflavone, and licoisoflavone A were submitted to D3Targets-2019-nCoV for molecular docking against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and RdRp. The backend docking process was performed by smina (58), which is a fork of AutoDock Vina (59). For further analysis, the docking conformation with the best docking score was chosen for each compound.

Anti-Inflammatory Activity Assay.

Anti-inflammatory activity assay based on SFTSV-infected inflammatory cell model was performed as described below. THP-1 cells were differentiated into macrophages by treatment with 40 ng/mL phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) in RPMI-1640 medium for 24 h, followed by resting for 24 h without PMA. THP-1 macrophages were infected with SFTSV at an MOI of 5, and the bioactive compounds at the indicated concentrations were added 1 h after incubation. Cells and supernatants were collected 48 h postinfection. Proteins in supernatants were precipitated with an equal volume of methanol and a quarter volume of chloroform as described previously (39). The cell lysates and dissolved precipitants in supernatants were subjected to western blot analyses. The gray values of protein bands were analyzed with ImageJ.

Anti-inflammatory activity assay based on SARS-CoV-2-infected inflammatory cell model was performed as described below. Calu-3 cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 at an MOI of 0.1 in the presence of licochalcone B, glycyrrhisoflavone, and echinatin at the indicated concentrations. Cells and supernatants were harvested 48 h postinfection, and proteins in cell lysates and supernatants were subjected to western blot analyses as described above. The gray values of protein bands were analyzed with ImageJ.

PDE4 Inhibition Assay.

The activity of the purified catalytic domain of PDE4 was monitored by measuring the hydrolysis of [3H]-cAMP into [3H]-AMP using the phosphodiesterase SPA. Three independent experiments were conducted for the determination of the IC50 values of each compound. An approved oral, selective small-molecule inhibitor of PDE4, apremilast (Shanghai yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China, purity ≥ 99%), was used as a positive control (60, 61). All experimental data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, version 8.0 (GraphPad Inc.). Detailed information on the protocols is provided in SI Appendix, Supplement 8.

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

Crystallization of apo PDE4 was performed at 4 °C using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing equal volumes of the protein at 18 mg/mL with a buffer of 18% (w/v) PEG3350, 0.1 M HEPES (pH 6.5 to 7.5), 0.2 M MgCl2, 10% (v/v) isopropanol, and 30% (v/v) ethylene glycol. Apo crystals were soaked with 5 to 10 mM compounds for 12 h at 4 °C with a final concentration of 2 to 4% DMSO. Using commercial perfluoropolyether cryo oil (PFO) as a cryoprotectant, the crystals were flash-frozen into liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at beamline BL02U1 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Shanghai, China) (62). The data were processed with HKL3000 software packages (63). Based on the search model with PDB code 7CBQ (64), the structure was solved by molecular replacement using the CCP4 program (65). The models were built using Coot (66) and refined with a simulated annealing protocol implemented in the program PHENIX (67).

Statistical Analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's or Dunnett's post hoc tests for comparison of multiple columns and unpaired two-tailed t tests for comparisons between groups. Differences were considered statistically significant when the P value was <0.05.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Dataset S05 (XLSX)

Dataset S06 (XLSX)

Dataset S07 (XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We are immensely grateful to our respective universities and institutes for their technical assistance and valuable support during the completion of this research project. This study was funded by the Key Project at the Central Government Level: The Ability Establishment of Sustainable Use for Valuable Chinese Medicine Resources (2060302 to J.Q., K.P., Y.X., H.X., and L.H.) the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81830111 to H.X.), the Establishment of Sino-Austria “Belt and Road” Joint Laboratory on Traditional Chinese Medicine for Severe Infectious Diseases and Joint Research (2020YFE0205100 to H.X.). We would also like to thank Prof. Qiang Ding, School of Medicine, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, for the SARS-CoV-2-trVLPs system and his guidance and help with the experiments.

Author contributions

H.J., G.F.G., and L.H. designed research; H.X., Shao Li, J.L., J. Chen, L.K., Y. Zhong, C.W., L.F., Y. Zhang, M.Y., Zhenxing Zhou, C.Z., H.S., S.Y., Zhaoyin Zhou, Yulong Shi, R.D., Q.L., F.L., F.Q., J. Cheng, S.Z., and X.M. performed research; Z.X. and Shufen Li contributed new reagents/analytic tools; and H.X., W.L., J.Q., Y.X., K.P., Yi Shi, G.F.G., and L.H. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interest.

Footnotes

Reviewers: R.B., Karl-Franzens-Universitat Graz; and G.G., University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Contributor Information

George F. Gao, Email: gaof@im.ac.cn.

Luqi Huang, Email: huangluqi01@126.com.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Zhou P., et al. , A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N., et al. , A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 727–733 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C., et al. , Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China. Lancet 395, 497–506 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon C. J., et al. , Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 6785–6797 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jayk Bernal A., et al. , Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 509–520 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saravolatz L. D., Depcinski S., Sharma M., Molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir: Oral Coronavirus disease 2019 antiviral drugs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, 165–171 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Najjar-Debbiny R., et al. , Effectiveness of paxlovid in reducing severe COVID-19 and mortality in high risk patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankar-Hari M., et al. , Association between administration of IL-6 antagonists and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Jama 326, 499–518 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zumla A., Hui D. S., Perlman S., Middle east respiratory syndrome. Lancet 386, 995–1007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Kuraishy H. M., et al. , Sequential doxycycline and colchicine combination therapy in Covid-19: The salutary effects. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 67, 102008 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottlieb R. L., et al. , Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: A randomized clinical trial. Jama 325, 632–644 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J., Artemisinin, the magic drug discovered from traditional Chinese medicine. Engineering 5, 32–39 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tu Y., The discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and gifts from Chinese medicine. Nat. Med. 17, 1217–1220 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan W., et al. , A novel coronavirus genome identified in a cluster of pneumonia cases - Wuhan, China 2019–2020. China CDC weekly 2, 61–62 (2020). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong Y., et al. , The effect of Huashibaidu formula on the blood oxygen saturation status of severe COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytothera. Phytopharmacol. 95, 153868 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao C., et al. , Chinese medicine formula huashibaidu granule early treatment for mild COVID-19 patients: An unblinded, cluster-randomized clinical trial. Front. Med. 8, 696976 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L., et al. , Association between use of Qingfei Paidu Tang and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A national retrospective registry study. Phytomedicine 85, 153531 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong W. Z., Wang G., Du J., Ai W., Efficacy of herbal medicine (Xuanfei Baidu decoction) combined with conventional drug in treating COVID-19: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Integra. Med. Res. 9, 100489 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z., Zhang J., Zhan J., Gao H., Screening out anti-inflammatory or anti-viral targets in Xuanfei Baidu Tang through a new technique of reverse finding target. Bioorg. Chem. 116, 105274 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Runfeng L., et al. , Lianhuaqingwen exerts anti-viral and anti-inflammatory activity against novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Pharmacol. Res. 156, 104761 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu L., et al. , Mechanism of microbial metabolite leupeptin in the treatment of COVID-19 by traditional Chinese medicine herbs. mBio 12, e0222021 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su H., et al. , Identification of pyrogallol as a warhead in design of covalent inhibitors for the SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease. Nat. Commun. 12, 3623 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niu W. H., et al. , Network pharmacology for the identification of phytochemicals in traditional Chinese medicine for COVID-19 that may regulate interleukin-6. Biosci. Rep. 41, BSR20202583 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J., et al. , Combination of Hua Shi Bai Du granule (Q-14) and standard care in the treatment of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A single-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Phytomedicine 91, 153671 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi N., et al. , Efficacy and safety of Chinese herbal medicine versus Lopinavir-Ritonavir in adult patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A non-randomized controlled trial. Phytomedicine 81, 153367 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei W. L., et al. , Chemical profiling of Huashi Baidu prescription, an effective anti-COVID-19 TCM formula, by UPLC-Q-TOF/MS. Chinese J. Nat Med. 19, 473–480 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y., et al. , SoFDA: An integrated web platform from syndrome ontology to network-based evaluation of disease–syndrome–formula associations for precision medicine. Sci. Bull. 67, 1097–1101 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu Y. W., et al. , Analyzing the potential therapeutic mechanism of Huashi Baidu Decoction on severe COVID-19 through integrating network pharmacological methods. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 11, 180–187 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y., et al. , Deciphering the active compounds and mechanisms of HSBDF for treating ALI via integrating chemical bioinformatics analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 879268 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bao L., et al. , The pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in hACE2 transgenic mice. Nature 583, 830–833 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Z., et al. , A novel STING agonist-adjuvanted pan-sarbecovirus vaccine elicits potent and durable neutralizing antibody and T cell responses in mice, rabbits and NHPs. Cell Res. 32, 269–287 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu H. Y., et al. , ETCM: An encyclopaedia of traditional Chinese medicine. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D976–D982 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu Y., Ju X., Ding Q., A nucleocapsid-based transcomplementation cell culture system of SARS-CoV-2 to recapitulate the complete viral life cycle. Bio Protocol. 11, e4257(2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi Y., et al. , D3Targets-2019-nCoV: A webserver for predicting drug targets and for multi-target and multi-site based virtual screening against COVID-19. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 10, 1239–1248 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li S., et al. , SFTSV infection induces BAK/BAX-dependent Mitochondrial DNA release to trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Rep. 30, 4370–4385.e4377 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Q., He B., Huang S. Y., Wei F., Zhu X. Q., Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, an emerging tick-borne zoonosis. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 14, 763–772 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mangalmurti N., Hunter C. A., Cytokine storms: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 53, 19–25 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J. W., et al. , SFTSV infection induced interleukin-1β secretion through NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front. Immunol. 12, 595140 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li S., et al. , SARS-CoV-2 triggers inflammatory responses and cell death through caspase-8 activation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 5, 235 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S., et al. , SARS-CoV-2 Z-RNA activates the ZBP1-RIPK3 pathway to promote virus-induced inflammatory responses. Cell Res. 33, 201–214 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen H. Y., et al. , 5-hydroxymethylcytosine signatures in circulating cell-free DNA as early warning biomarkers for COVID-19 progression and myocardial injury. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 781267 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baell J., Walters M. A., Chemistry: Chemical con artists foil drug discovery. Nature 513, 481–483 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingolfsson H. I., et al. , Phytochemicals perturb membranes and promiscuously alter protein function. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 1788–1798 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang K., et al. , Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the treatment of COVID-19 and other viral infections: Efficacies and mechanisms. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 225, 107843 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyu M., et al. , Traditional Chinese medicine in COVID-19. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 3337–3363 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li L., et al. , Potential treatment of COVID-19 with traditional chinese medicine: What herbs can help win the battle with SARS-CoV-2? Engineering 19, 139–152 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niu W., et al. , Network pharmacology analysis to identify phytochemicals in traditional Chinese medicines that may regulate ACE2 for the treatment of COVID-19. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2020, 7493281 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maurice D. H., et al. , Advances in targeting cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 13, 290–314 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang K. Y. J., Ibrahim P. N., Gillette S., Bollag G., Phosphodiesterase-4 as a potential drug target. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 9, 1283–1305 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu H. Y., et al. , A comprehensive review of integrative pharmacology-based investigation: A paradigm shift in traditional Chinese medicine. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 1379–1399 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu C. X., et al. , Herb-drug interactions involving drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Curr. Drug. Metab. 12, 835–49 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang X. H., et al. , Mice transgenic for human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 provide a model for SARS coronavirus infection. Comparat. Med. 57, 450–459 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peng Q., et al. , Structural and biochemical characterization of the nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 core polymerase complex from SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 31, 107774 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X., Dong G., Li H., Chen W., Xu Y., Structure-aided identification and optimization of tetrahydro-isoquinolines as novel PDE4 inhibitors leading to discovery of an effective anti-psoriasis agent. J. Med. Chem. 62, 5579–5593 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bai Y., et al. , Structural basis for the inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease by the anti-HCV drug narlaprevir. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 6, 51 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng J., Li D., Zhang J., Yin X., Li J., Crystal structure of SARS-CoV 3C-like protease with baicalein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 611, 190–194 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sen D., et al. , Identification of potential edible mushroom as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor using rational drug designing approach. Sci. Rep. 12, 1503 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koes D. R., Baumgartner M. P., Camacho C. J., Lessons learned in empirical scoring with smina from the CSAR 2011 benchmarking exercise. J. Chem. Inf. Model 53, 1893–1904 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trott O., Olson A. J., AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wegesser T., Coppi A., Harper T. Jr., Paris M., Minocherhomji S., Nonclinical genotoxicity and carcinogenicity profile of apremilast, an oral selective inhibitor of PDE4. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. RTP 125, 104985. (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zebda R., Paller A. S., Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 78, S43–s52 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Q. S., et al. , Upgrade of macromolecular crystallography beamline BL17U1at SSRF. Nucl Sci. Tech. 29, 7 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Minor W., Cymborowski M., Otwinowski Z., Chruszcz M., HKL-3000: The integration of data reduction and structure solution–from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. D 62, 859–866 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang R., Li H., Zhang X., Li J., Liu H., Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of tetrahydroisoquinolines derivatives as novel, selective PDE4 inhibitors for antipsoriasis treatment. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 211, 113004 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bailey S. M., The ccp4 suite - programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. 50, 760–763 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Emsley P., Cowtan K., Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Li W. H., Ioerger T. R., Terwilliger T. C., PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. 58, 1948–1954 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Dataset S05 (XLSX)

Dataset S06 (XLSX)

Dataset S07 (XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.