Abstract

Past research suggests that psychosocial responses to advanced or recurrent cancer varies by age. This study compares the relative influences of patients’ age and recurrence status on indicators of symptom distress, anxiety and depression following a diagnosis of advanced cancer. A prospective study of advanced cancer support provided patient outcome data reported at baseline, 3 and 6 month intervals. Cohorts were defined by age group and recurrence status and latent growth curves fit to anxiety, depression, and symptom distress outcomes. Middle aged recurrent patients reported the highest symptom distress, depression, and anxiety across time points. Older recurrent patients fared worse at baseline than older non-recurrent patients, but outcome scores converged across time points. Recurrent cancer presents a distinct challenge that, for middle aged patients, persists across time. It may be beneficial to develop targeted educational and support resources for middle-aged patients with recurrent disease.

Keywords: age differences, distress, anxiety, depression, cancer recurrence

An adult cancer patient’s first diagnosis of cancer is a highly stressful event, likewise, a cancer recurrence after a period of disease free time can return these patients to previous levels of distress. A solid tumor cancer recurrence is most often not curable (i.e., advanced) introducing a revised prognosis and recalculation of hope (Beadle et al., 2004; Cella, Mahon, & Donovan, 1990; Reynolds, 2008). Although recurrent and non-recurrent advanced cancer patients both face a limited prognosis, little is known about how recurrent patients’ psychosocial needs may differ from those of non-recurrent patients who are receiving an advanced cancer diagnosis for the first time. Both types of patients face a chronic, terminal condition, but the recurrent patient encounters a unique paradox of simultaneous familiarity and uncertainty. These patients have already completed a course of treatment, marshaled support and coped with the uncertainty of a cancer diagnosis before. Although several factors may contribute to how advanced and recurrent patients adjust to their diagnosis, key among them is the patient’s age.

A large body of evidence supports the idea that older patients report better emotionally related outcomes during cancer care (Parker, Baile, De Moor, & Cohen, 2003; Rose, 1993; Rose, et al., 2004; Salvo et al., 2012; Silliman, Dukes, Sullivan, & Kaplan, 1998; Yang, Thornton, Shapiro, & Andersen, 2008). While life events and responsibilities change across the lifespan, aging also offers both a developmental benefit, that is, a distinct perspective on stress and challenge, as well as a learned coping benefit gained as a result of accumulated experience (Baltes & Carstensen, 1996; Folkman, Lazarus, Pimley, & Novacek, 1987; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004). This coping benefit is similar to gains reported by recurrent patients describing their return to active disease (Step & Ray, 2011). However, questions remain as to the robustness of this aging effect, or if it differs in the event of recurrence. The purpose of this study is to examine the relative influences of age and recurrence status on the reported levels of symptom distress, anxiety and depression by newly diagnosed advanced cancer patients.

Cancer recurrence as a psychosocial experience

Diverse tumor biology across body systems prevents calculation of a general recurrence rate among cancer patients. Nevertheless, there is little doubt that recurrence is a pivotal psychosocial event for patients and families. Cancer recurrence has been associated with decreases in mood and quality of life, reduced functional performance, economic burden, and a changed identity for person and caregivers (Howell, Fitch, & Deane, 2003; Lamerato, Havstad, Gandhi, Jones, & Nathanson, 2006; Mahon & Casperson, 1995; Newsom, Knapp, & Schulz, 1996; Schulz et al., 1995). Given the gravity of a recurrence diagnosis, distress is a commonly tracked patient reported outcome, yet a definitive pattern of experience remains inconclusive. Some researchers report no change in self-reported distress from the first to second diagnosis (Andersen, Shapiro, Farrar, Crespin, & Wells-DiGregorio, 2005; Howell et al., 2003; Worden, 1989), but others provide evidence for significantly higher distress at recurrence (Mahon & Casperson, 1995; Weisman & Worden, 1986). Kenne Sarenmalm reported that distress declined over time among a sample of recurrent breast cancer patients, peaking at 3 months after the diagnosis (Cella et al., 1990; Kenne Sarenmalm, Öhlén, Odén, & Gaston-Johansson, 2008). Yang et al’s study (Yang, Brothers, & Andersen, 2008) of a small sample of recurrent breast cancer patients suggest that recurrence is indeed a highly stressful event, but that a person’s coping response (i.e., engaged or disengaged) mediates the relationship between the patient’s distress and quality of life. In any case, cancer related distress is a pivotal patient outcome that varies between patients and across the cancer trajectory (Jim & Andersen, 2007; Kenne Sarenmalm et al., 2008).

Within the psychosocial domain, depression is also a concerning patient outcome associated with recurrence. Baseline depression and attitudes about the general controllability of cancer have been identified in various studies as contributors to depression (Jenkins, May, & Hughes, 1991; Newsom, Knapp & Schulz, 1996; Okano et al., 2001). Among a small sample of recurrent breast cancer patients, 22% suffered major depressive disorder (MDD) (Okamura, Yamawaki, Akechi, Taniguchi, & Uchitomi, 2005). In this study, MDD significantly predicted lower functioning and higher symptomology in quality of life measures. Other reviews and descriptive studies show that depression tends to be relatively low across cancer sub-populations and depends largely on being a younger age and previous levels of depression (Miovic & Block, 2007; Okamura et al., 2005; Parker et al., 2003; Salvo et al., 2011; Yang, et al., 2008).

Although any cancer diagnosis is likely to be stressful, anxiety is an aspect of health experiences that serves as a key predictor of information processing and adjustment (Hulbert-Williams, Neal, Morrison, Hood, & Wilkinson, 2011; Husson, Mols, & Van de Poll-Franse, 2011; Spencer, Nilsson, Wright, Pirl, & Prigerson, 2010). Anxiety has shown variable prevalence across studies of recurrent patients. Although some reviews show that recurrent cancer patients return to high levels of anxiety, (Vivar, Canga, Canga, & Arantzamendi, 2009; Warren, 2009), other studies show patients report lower anxiety levels at recurrence (Weisman & Worden, 1986; Yang, Thornton, et al., 2008). There is suggestion here that recurrence releases patients from the stress of surveillance (Worden, 1989). However, across cancer in general, and much like depression, anxiety following diagnosis and is generally best predicted by personality, age, female gender and performance status (Hulbert-Williams et al., 2011; Parker et al., 2003; Salvo et al., 2011). Importantly, these psychosocial indicators fluctuate across the months following a diagnosis.

Clinically relevant levels of distress, depression, and anxiety would not be surprising after receiving any cancer diagnosis, but questions remain regarding the persistence of these symptoms, particularly in the face of coping experience gained from a prior diagnosis or the emotional benefits of aging. Recent research has established that emotional effects of having cancer do not occur in isolation from other mental processes. Rather, there are interesting associations with cognition, such as illness appraisals or coping strategies, that seem to mediate adjustment to a cancer diagnosis (Husson et al., 2011; Rose, et al., 2004; Tomich & Helgeson, 2006; Yang, et al., 2008). For example, Hulbert-Williams et al., found that women’s cognitive appraisals of cancer were most predictive of anxiety and depression across several solid tumor types of non-recurrent cancer diagnoses (Hulbert-Williams et al., 2011). Others found coping style to mediate psychosocial outcomes among recurrent patients. Recurrence status should play an important role in determining illness cognitions or coping strategies. Although recurrent patients can have new disease concerns, they may find a coping resource in familiar personnel, routines, or regimens learned over time (Step & Ray, 2011).

Cancer adjustment over time

Adjusting to a life with cancer is marked by many clinical events, changing meanings, and support needs. Patients and caregivers can learn much over time, from a variety of sources and experiences (Morton & Duck, 2001). Prospective studies show that emotional responses to illness fluctuate, often stabilizing in the months following diagnosis (Andersen et al., 2005; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2011; Rose et al., 2008; Stanton, Danoff-Burg, & Huggins, 2002). Although some small studies suggest it, whether or not recurrence status provides any independent benefit to patient reported emotional outcomes is unknown. However, much is known about the association of emotional development and aging.

Age and emotional processing

Adjusting to a recurrence diagnosis may be bolstered by previous experience as well as developmental adaptation across the lifespan. A growing, cross-disciplinary, body of research has identified several age-related processes relevant to coping and adjustment to cancer. Compared to younger people older people experience less negative emotion such as anger, anxiety or fear (Phillips, Henry, Hosie, & Milne, 2006; Schieman, 1999; Tsai, Levenson, & Carstensen, 2000). Others have shown older adults experience a co-occurrence of positive and negative emotion (Carstensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000; Ersner-Hershfield, Mikels, Sullivan, & Carstensen, 2008; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2008). This kind of dual emotional processing serves as a means of optimizing and enhancing meaningful life goals over time (Baltes & Carstensen, 1996; Baltes & Baltes, 1990).

Coping with advanced cancer often necessitates clarifying and shifting life goals while simultaneously constructing strategies for managing the treatment phase and beyond. As the disease progresses, patients may need to adjust personal goals of independence, emotional support, home care and hospice (Mor, 1987, 1992). These adaptive processes and needs for support may differ for older patients (Mor, Allen, & Malin, 1994; Rose, 1993). For example, not only do older cancer patients report better quality of life, (Arden-Close, Gidron, & Moss-Morris, 2008; Parker et al., 2003; Zimmermann et al., 2010), but they are also more likely to quickly stabilize and adapt to a cancer diagnosis (Rose, Bowman, Radziewicz, Lewis, & O’Toole, 2009). Although various bio-psychological mechanisms may account for this difference, at their root is the accumulated benefit of learning from past experiences (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999; Folkman et al., 1987; Kolb, Boyatzis, & Mainemelis, 2001; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004).

Consequently, having had a prior cancer and older age offer the potential benefit of accumulated experience with coping. The coping advantages associated with aging are well established, but less is known about how older adults adjust to a cancer recurrence. Further, although several studies compare a patient’s first and recurrent experience, less is known about how recurrent cancer may differ from a first diagnosis of advanced cancer (Munkres, Oberst, & Hughes, 1992; Parker et al., 2003; Schulz et al., 1995). Because solid tumor cancer recurrence typically occurs at an advanced (i.e., metastatic) stage, it can be readily compared to more general patient experiences with a first diagnosis of advanced cancer. From the patient’s perspective, both recurrent and non-recurrent advanced cancers share an incurable, limited prognosis. Even though length of prognoses may vary across tumor types, anxiety, depression and symptom distress is challenging for either type of patient. It is in relation to this, more emotionally driven experience that age should prove to be a significant factor.

In order to better understand how to tailor education and support to patients, it is necessary to explore potential differences in adaptation across recurrence status and age groups. Given past research demonstrating a positive advantage to older adults, it is expected that older, recurrent cancer patients are well positioned to adjust to a second, now advanced, cancer diagnosis.

H1: Older recurrent patients will report the lowest distress, depression and anxiety scores.

Conversely, it is also hypothesized that middle aged, non-recurrent patients will be more challenged by the new diagnosis.

H2: Middle aged, non-recurrent patients will report the highest distress, depression, and anxiety scores.

Moreover, it is hypothesized that these outcomes will be highest at baseline and stabilize over time. This study tests these propositions over the first several months following either a first-time advanced or distant recurrent cancer diagnosis. Because of the many factors that can influence these outcomes, we retain an exploratory stance on the compared rates of change.

RQ1: What are the rates of change over time for patient groups defined by age and recurrence status?

Method

Data Source and Sample Creation

This study utilized data collected from advanced cancer patients who participated in a prospective randomized control trial test of a supportive care intervention (Rose, Radziewicz, Bowman, & O’Toole, 2008). Study participants were seeking treatment for advanced cancer from a large county hospital and nearby Veterans Administration hospital. Following IRB approval at both institutions, non-hospitalized patients were recruited, enrolled and randomly assigned to either an intervention or control arm of the RCT within 10 weeks of receiving a diagnosis of advanced cancer. There were no differences in intervention assignment across age or recurrence status groups. A chart review and screening interview prior to an in person baseline interview provided data for demographic and disease related variables. Outcome measures assessed in the current study were collected in the baseline interview (n = 564), and again in, telephone follow-up interviews at three (n = 429) and six (n = 338) month intervals.

In order to track and compare outcome trajectories, A 2 × 2 (recurrence status x age group) cohort group was created. Overall, at baseline, study participant ages ranged from 40–84 (m = 61.3; sd = 10.28). Age cohorts were created by a median (med = 60.0) split, producing middle aged (40–60; n = 273) and young-old groups (61–80; n = 291). Recurrence status was established with a medical record review. Cancer recurrence was defined as the return of a previously diagnosed primary cancer following a disease free interval of at least six months. Given the RCT pre-requisite of an advanced cancer diagnosis, all identified recurrences were distant in nature. Recurrence status was typically evidenced either in the patient’s medical history or physicians’ notes sections of the EMR. Of the baseline sample, 100 patients met the recurrence status criteria. No significant differences in recurrence status or age were detected across patients randomly assigned to the intervention or control arms of the RCT. The recurrent sample showed a similar rate of attrition from the RCT study as the larger sample frame (see Table 1).

Table 1:

Cohort Sample Size Over Time

| Middle Age Recurrent (MA-REC) | Young-Old Recurrent (YO-REC) | Middle Age Non-Recurrent (MA-NON) | Young Old Non-Recurrent (YO-NON) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=564) | 57 | 43 | 216 | 248 |

| 3 Months (n=429) | 43 | 34 | 168 | 184 |

| 6 Months (n=338) | 35 | 31 | 129 | 143 |

Demographic variables for groups defined by age cohort and recurrence status are summarized in Table 2. ANOVA analysis was conducted across cohort groups for each demographic variable. Results showed a significantly greater percentage of females in the recurrent cohort and significantly more co-morbidities and higher percentage of married people in the young-old age group. Primary tumor sites were also examined for differences across the cohort groups (see Table 3). Lung cancer is the most common primary cancer site in all groups except for the young-old recurrent group who showed genitourinary cancer most frequently. It is important to note that a substantial number of tumor sites fall into the “other cancer” category, particularly for middle aged, non-recurrent patients. This category includes skin, bone, tissue, and brain cancers.

Table 2:

Baseline Demographic Differences Between Age By Recurrence Status Cohorts

| Recurrent | Non-Recurrent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Middle Aged | Young Old | Middle Aged | Young Old | |||

| ANOVA m(sd) | df | F | p< | ||||

| Age | 52.6 (5.3) | 67.6 (4.4) | 53.6 (5.4) | 68.1 (5.9) | 3 | 262.71 | .0001 |

| Years of Education | 12.1 (2.3) | 12.5 (2.7) | 12.4 (2.2) | 12.4 (2.4) | 17 | 1.12 | .331 |

| Co-morbidities | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.6) | 8 | 3.73 | .0001 |

| CHI-Square n(%) | df | X 2 | P< | ||||

| Gender (% Female) | 31 (54.3) | 20 (52.6) | 67 (31.0) | 51 (23.8) | 3 | 27.12 | .0001 |

| Marital Status (% Married) | 20 (35.7) | 26 (68.4) | 65 (30.2) | 107 (50.0) | 12 | 55.90 | .0001 |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 33 (57.9) | 29 (76.3) | 124 (57.4) | 147 (68.3) | 12 | 15.78 | .201 |

Table 3:

Distribution of tumor sites across groups

| Tumor Site | MA-REC | YO-REC | MA-NON | YO-NON |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast (n=34) | 11 (32%) | 5 (15%) | 10 (29%) | 8 (23%) |

| Lung (n=187) | 15 (8%) | 7 (3%) | 82 (43%) | 83 (44%) |

| Gastrointestinal (n=56) | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 17 (30%) | 35 (62%) |

| Genitourinary (n=125) | 13 (10%) | 9 (7%) | 56 (45%) | 47(38%) |

| Gynecologic (n=29) | 7 (24%) | 8 (27%) | 6 (21%) | 8 (28%) |

| Other (n=95) | 9 (9%) | 7 (7%) | 45 (47%) | 34 (36%) |

Measurement

The primary goal of this study is to compare the trajectories of patient distress, depression and anxiety across age and recurrence status groups. All outcome measures were self-reported by patients at each data collection point in interviews with research staff (See Table 4).

Table 4:

Outcome variables

| Construct | Measure (n of items) | Range | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom Distress | Modified Symptom Distress Scale (13) | (13–65) | Normal/no distress = 1; Extensive distress = 5 | .91 |

| Depression | Profile of Mood States-short form (8) | (0–32) | Not at all = 0; Very much = 4 |

.93 |

| Anxiety | Profile of Mood States-short form (6) | (0–24) | Not at all = 0; Very much = 4 |

.83 |

Outcome measures.

Symptom distress was measured with McCorkle and Young’s (1978) Modified Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) (McCorkle & Young, 1978). This 13 item scale assesses the degree of discomfort from specific cancer-related symptoms reported by the patient including: appetite, insomnia, pain presence and intensity, fatigue, bowel function, concentration, appearance, breathing, outlook, cough, and nausea presence and intensity. The modified SDS has been used with a wide variety of cancer populations, and settings. Patients rated each symptom on a 5-point response format ranging from “normal or no distress to extensive distress.” Responses were summed for a total score with high scores reflecting greater distress. Cronbach alpha reliability at baseline is 0.83.

Anxiety and depression were measured with the Profile of Mood States-short form (POMS-sf). The POMS-sf measure is a valid and reliable tools for assessing mood disturbance (Cella et al., 1987). The POMS-sf was designed to minimize burden for physically ill patients and offers brief, valid and highly reliable subscales including those included in this study: patient perceived anxiety and depressed mood (McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1992). Scale items (n = 7) for anxiety included: “unhappy”, “restless”, “discouraged”, “nervous”, “worthless”, “tense”, and “on edge”. Scale items (n = 7) for depression included: ”helpless”, “sad”, “uneasy”, “hopeless”, “miserable”, “anxious” and “blue”. These measures were administered by asking the person how much of each discrete feelings the person had during the past week. Adjectives representing subscale qualities (e.g., miserable, edgy) were paired with intensity scales (0=Not at All-4=Extremely) and summed (Curran, Andrykowski, & Studts, 1995). The Cronbach alpha indicating item reliability for the anxiety subscale is 0.89 and 0.92 for depression subscale.

Control variables.

Several variables from the RCT screening and baseline interviews were included in analyses as covariates. First, patients’ physical status was assessed in a count of co-morbidities documented in chart reviews. Documented co-morbidities included all non-cancer conditions in the Charlson Index (Charlson, Rompei, & Ales, 1987) plus conditions common in older adults (i.e., arthritis, hypertension) (Fillenbaum, 1988). Second, limitations in basic activities of daily living (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963) and instrumental activities of daily living (Fillenbaum, 1988) were measured in baseline interviews. Finally, patient’s intervention status (intervention/control), weeks from diagnosis to enrollment, gender, marital status, years of education, and race/ethnicity were controlled in all subsequent analyses.

Analysis

The first phase in the analysis explored potentially significant differences in symptom distress, depression, anxiety across the age by recurrence status groups at the time of study enrollment. Oneway ANOVA was conducted for each outcome variable followed by post hoc Scheffe comparison tests. Stata 11 (StataCorp. 2009) was used for this part of the analysis.

The next phase of the analysis compared the outcome trajectories for age by recurrence status groups six months after baseline assessment. Essentially, we assessed whether these groups change in the same ways across time. The study of cohort groups’ trajectories after a stage IV or recurrent diagnosis presents several unique methodological challenges. Traditional methods of repeated measures (ANOVA and ANCOVA) do not allow the modeling of both within patients’ and between group’s means and variances. First, ANOVA/ANCOVA do not explicitly model inter-individual differences in change, that is, random effects. Second, ANOVA/ANCOVA assume that measurements taken at different times have uncorrelated errors. In the current study each subject has three measurements (i.e., baseline, 3 and six months) and the errors for those measurements will almost surely be correlated. Third, ANOVA/ANCOVA assumes that missing data are MCAR (Missing Completely at Random), an implausible assumption in almost all models. A more appropriate way to deal with missing data is to assume MAR (Missing at Random). We applied the mixed-effects methodology (i.e., multi-level or hierarchical models) which addresses all three limitations of the ANOVA/ANCOVA modeling framework, to analyze our longitudinal data. Additionally, the ANOVA/ANCOVA methodology is limited in handling dropout and individually varying times of observations (i.e., unbalanced data). The analysis plan reflects recent methodological developments appropriate for these complexities (Schafer & Yucel, 2002). We used Mplus version 6.1 (Muthén,& Muthén, 2010).

Results

Hypothesis 1 and 2 were partially supported. Group differences appear to be between middle and young-old age groups rather than recurrence status groups (See Table 5). It should be noted that the mean for middle aged recurrent patients symptom distress is the highest of the four groups, but only significantly higher than both young-old groups. The young old recurrent group shows the lowest distress but fell short of statistical significance. There was a similar pattern for both anxiety and depression. Middle aged recurrent patients reported the highest depression and anxiety levels, but post hoc comparisons did not establish a significant difference between middle aged recurrent and middle aged non-recurrent groups. Young old recurrent patients report the lowest outcome scores at baseline, and though significantly lower from middle aged patients, are not significantly different from young old non-recurrent patients. After controlling for other demographics and illness factors, age alone appears to be playing a stronger role than an age by recurrence status interaction.

Table 5:

Baseline Outcome Differences Between Groups

| Group | MA-REC m (sd)/% |

YO-REC | MA-NON | YO-NON | P< |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Symptom Distress | 32.4 (9.1)2,4 | 24.9 (6.4)1,3 | 29.9 (9.3)2,4 | 26.1 (7.5)1,3 | .0001 |

| Depression | 11.5 (8.3)2,4 | 5.9 (7.3)1,3 | 9.4 (8.5)2,4 | 7.0 (7.1)1,3 | .0001 |

| Anxiety | 10.4 (6.8)2,4 | 5.6 (6.1)1,3 | 9.5 (6.3)2,4 | 6.8 (5.4)1,3 | .0001 |

Superscript identifies significantly different groups.

Mixed-effects models were used to derive expected change over time and to quantify between and within patient variability (Muthen & Muthen, 2000). Group trajectories reveal that the age by recurrence status cohorts differ in both initial levels and rate of change. The random effects (i.e. initial level and rate of change) of the outcome variables were further submitted to Wald tests of equality between groups. That is, we examined whether or not the observed differences in the random effects between the four groups were due to chance.

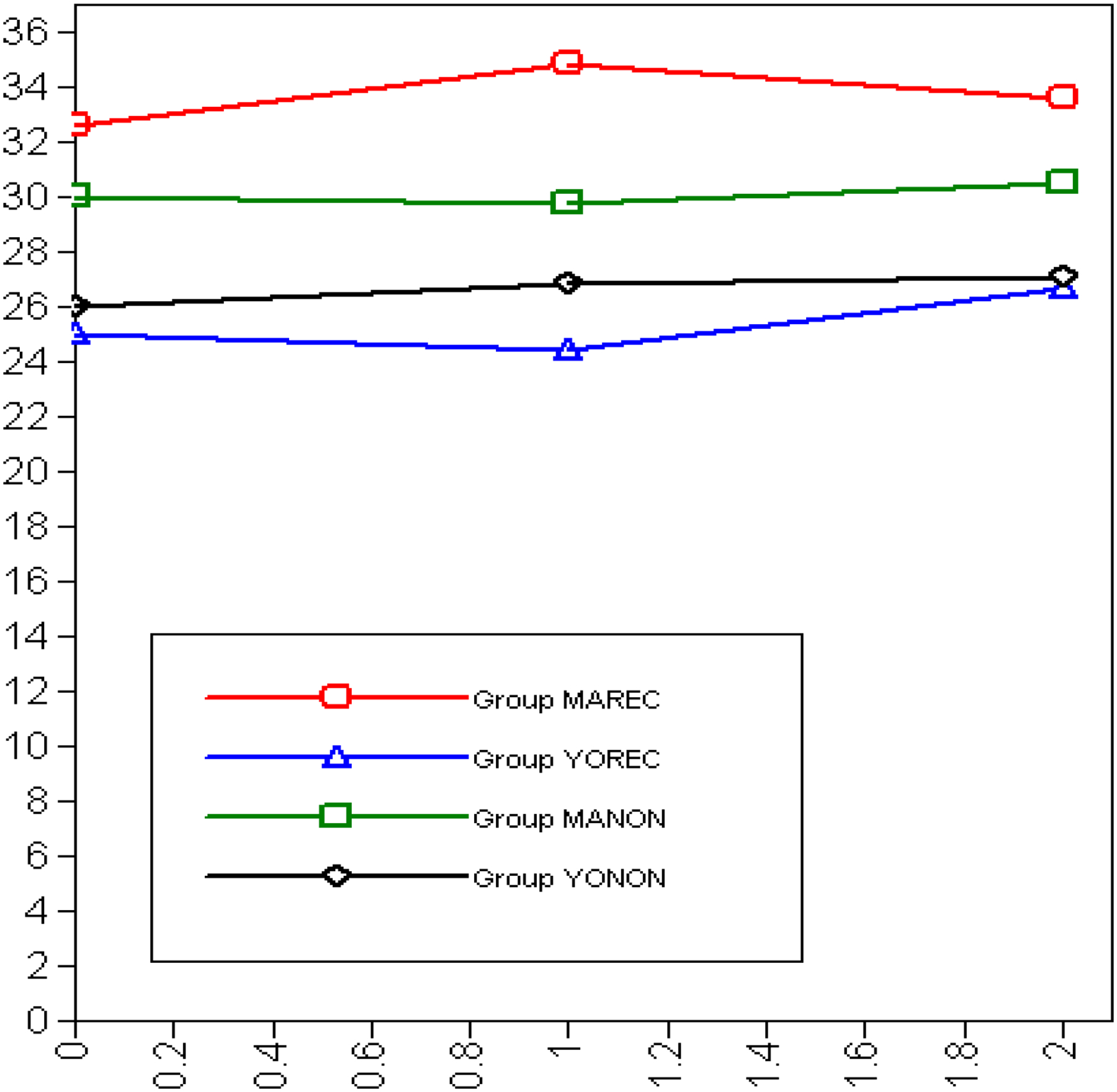

Symptom Distress:

Figure 1 presents the observed trajectories of the symptom distress outcome for the first six months after baseline stratified by recurrence status and age group. Young old recurrent patients appear to be less distressed than all other groups, followed by young old non–recurrent, middle aged non-recurrent, and middle aged recurrent reporting the most distress. All the groups seem to experience a stable level of symptom distress throughout the first six months after baseline.

Figure 1:

Symptom Distress Across Time Points

Depression:

Figure 2 illustrates the trajectories for depression across the cohort groups. All groups present a similar pattern regarding the rate of change: a decline in the first 3 months followed by a decrease in the decline rate from 3 to 6 months. There are significant differences among the groups in their respective initial levels, again both middle aged groups reporting higher levels of depression at baseline than the young old. Further, the middle aged recurrent group presents higher levels of depression than the middle aged non-recurrent group. Within the young old cohort the relationship is reversed and not as pronounced as the middle aged group. In addition, at the third (six month) time point, the young old group depression experience seem to converge to more similar levels. According to the Wald test of parameter constraint for comparing groups, the observed changes over time are not statistically significant (last column of table N). Nevertheless, all comparisons between age groups and between recurrence statuses indicate that the observed differences in the initial level are not due to chance. Although the age by recurrence status groups experience different levels of depression at baseline, they tend to show the same change patterns for the first 6 months. Finally, it is worth pointing out that the middle aged non-recurrent is the only group that experienced a statistically significant decline in depression for the first six months after baseline.

Figure 2:

Depression Across Time Points

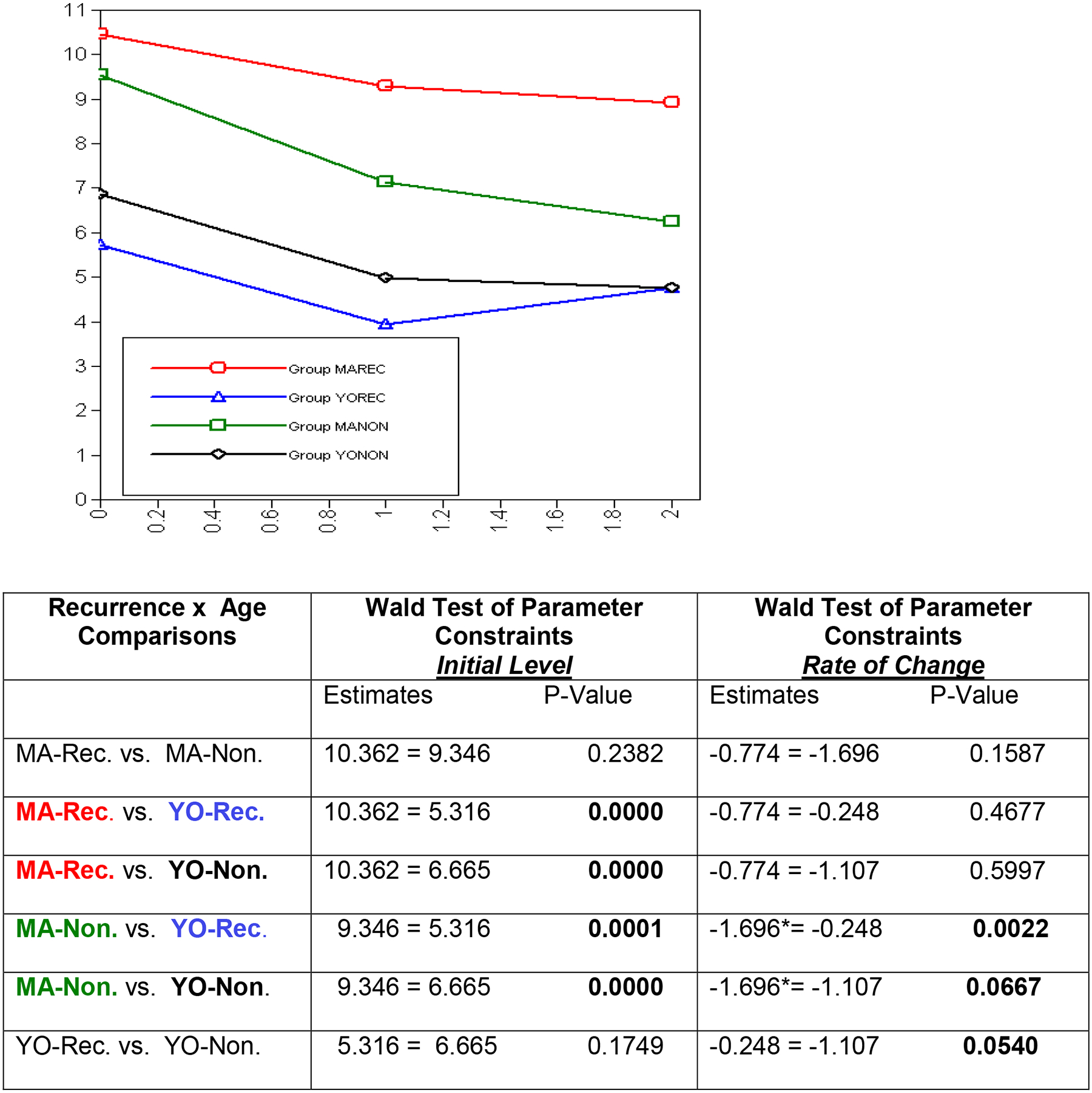

Anxiety:

The results for anxiety are somewhat different from depression (See Figure 3). Again, baseline differences are statistically significant between age group and recurrence status but, similar to depression, not within the age or recurrence status groups. However, for anxiety three out of the six comparisons show rates of change that are statistically significant from each other. Specifically, middle aged non-recurrent patients show a significant decrease in anxiety across the first six months following diagnosis (rate of change = −1.696, p < 0.05), whereas both young old groups (i.e., recurrent and non-recurrent) show less decline in anxiety, though not at a statistically significant rate. The observed difference in the rate of change between middle aged non-recurrent and young old recurrent is statistically significant as indicated by the Wald test. Comparisons between middle aged non-recurrent and young old non-recurrent (p = 0.0667), and young old recurrent and young old non-recurrent (p = 0.054) do not reach the set level of significance, but suggest different rates of change for these groups as well.

Figure 3:

Anxiety Across Time Points

Discussion

We expected older age and recurrence status to be facilitative conditions for adjusting to a diagnosis of advanced cancer. Advanced and recurrent patients who participated in a supportive intervention provided the sample for our analyses. Defined age groups (i.e., middle aged and young-old) were fairly evenly split at prospective time points, and recurrent patients comprised 18% of the baseline sample. This is comparable, but slightly lower than reported in other studies of mixed tumor site cancer patients (Andersen et al., 2005; Parker et al., 2003). One reason for this may be that the study population primarily consists of underserved patients, a group that typically presents their cancer at a more advanced stage (Clegg et al., 2009). These patients are not as likely to have received treatment at an early stage, thus precluding the opportunity for a recurrence. Other demographic trends that can be noted include significantly more co-morbidities among the older age group, and a greater percentage of recurrent females in both age groups. Though more co-morbidities is expected for older adults, a greater percentage of female recurrent patients is likely to be a function of tumor types represented in the sample. Predominant disease groups represented in the overall sample include lung (35%) and genitourinary (24%) cancer. However, 31% of the recurrent group are constituted by breast and gynecologic (i.e., female) tumor types, whereas those tumors are reported for only 7% of the non recurrent group. There are more female cancer types represented in the recurrent group. An unexpected finding in this sample is the greater percentage of married people among the older, rather than middle aged group. Being married is an important buffer to stressful events and could be contributing to the generally better outcomes of older aged adults in this sample (Goldzweig et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2003). Subsequent models of patient outcomes were adjusted to control for these variables.

Guided by evidence from literature reviews, studies of recurrent patients, and developmental theory, we expected middle aged, non-recurrent patients to have the most difficulty, and thus the highest distress, anxiety and depression, when adjusting to advanced cancer. However, baseline scores showed evidence of only a main effect for age rather than the interactive effect we predicted. Middle aged patients, regardless of recurrence status, reported greater distress, depression and anxiety than young old counterparts. Still, it was the middle aged recurrent patients who consistently reported the highest outcome scores at every time point. Conversely, we expected older recurrent adults to report the lowest outcome scores at each time point. This was also the case, though these differences failed to reach the set significance level. In general, the facilitative effects of aging on coping are well validated in the literature and here (Folkman et al., 1987; Parker et al., 2003; Rose, et al., 2004), but the effects of recurrence status fell short of indicating additional effects.

It is still unclear whether, or under what conditions, that having cancer a second time might help people adjust to an advanced cancer diagnosis, but age remains a plausible factor. It is possible that interactive effects, if they exist, would be better detected with other study designs and a larger or single tumor site sample. The NCI patient resource When Cancer Returns, suggests that the first cancer experience is an important resource for recurrent patients, providing insight on coping and care preferences (NCI, 2010). Although thinking about a cancer recurrence as a “resource” is a discomforting idea, experiencing treatment and related activities can reduce a great deal of uncertainty about what happens next for people with a recurrence. Both patients and caregivers often establish affectionate relationships with oncology staff and are quite familiar with the somatic experience of treatment. For this group, cancer is less a mystery, and more a logistical routine that they have managed in the past (Step & Ray, 2011). This is not to say that recurrent cancer does not present new, and more threatening possibilities, but the uncertainty of being completely new to the treatment process is tempered by lived experience. Though these data do not provide definitive confirmation of recurrence as resource, they do suggest some trends in that direction, especially for older patients.

This study also examined rates of change over time in symptom distress, anxiety, and depression for patient groups defined by age and recurrence status. Trajectories for each of these outcomes were stable and similar across the three outcomes. Middle aged patients consistently fared significantly worse in terms of distress, anxiety and depression and stay that way. This age-related finding is not unusual in cancer care and has been attributed to competing demands (e.g., children, employment) and expectations for a long life among middle age adults (Mor et al., 1994) as well as developmental changes in coping across the lifespan Tsai, et al., 2000.

Closer examination of the trajectories also suggested that within the middle aged group, recurrence status did indeed add a challenging effect. Although symptom distress scores remained relatively stable over the first six months after diagnosis, anxiety and depression scores suggested some interesting trends. Not only did middle aged recurrent patients report the highest anxiety and depression across time points, but the middle aged patients stayed significantly higher. In the case of anxiety, middle aged non recurrent patients showed a greater rate of change across time, and their scores converged more toward those of older adults. In other words, middle aged recurrent patients were not adjusting emotionally at the same rate as other patients. It appears from these data that the first three months after diagnosis is a critical window for delivering supportive care, particularly for middle aged patients. Future work should consider these age-related changes in emotional status over time, particularly as they relate to the timing of interventions.

Another trend worth noting is the convergence of outcome scores across some of the patient groups. For example, there is some suggestion that young old recurrent and young old non-recurrent adults converged in their reported scores at six months after diagnosis. The middle aged recurrent and non-recurrent adults maintained separate trajectories at each time point with no suggestion of convergence. These adults started off with higher depression and anxiety scores and stayed that way. Conversely, young old adults scores grew closer together over the six month data collection time frame. One reason for this difference may be found in how members of these groups perceived time horizons.

Time horizons affect perceptions.

How people cope with a cancer diagnosis is predictive of how meaning in life is construed as those people move on from receiving bad news (Jim, Richardson, Golden-Kreutz, & Andersen, 2006). Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST), suggests that boundaries on perceived time frames can prompt adults to prioritize emotional over task goals (Carstensen et al., 1999; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004). The shortened sense of time that accompanies older age forces a recalculation of what is most meaningful within the expected time frame. Though all of these patients faced shortening time horizon, those of older age and recurrent status had additional impetus to compensate for lost time and maximize positive affect. One challenge of aging is increasing frequency of illness and loss. Prior to living through their own diagnosis, older adults are likely to have lived through others’ illnesses, thus building their lay knowledge of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and coping. Conversely, middle aged patients with advanced cancer are in the vulnerable position of having a shortened time horizon, while engaged in active parenting, caregiving, or employment, and without the coping advantage of older age. Facing a life threatening illness in middle age dramatically interrupts these meaningful events and forces focus onto the uncertainties of disease and treatment. However, It is important to note that across all study waves (i.e., times), and for both age groups, symptom concerns were raised most frequently among those patients in our sample participating in the support intervention. (Radziewicz, Rose, Bowman, Lewis, & O’Toole, 2009). Existential issues were raised least often, in fact, in less than ten percent of support contacts per wave. Although, advanced cancer is indeed life threatening, in this early phase, immediately following diagnosis, patients in this sample expressed their concerns for more immediate issues. Nevertheless, given these circumstances and results, it may be that middle aged advanced cancer patients face a more difficult challenge than older adults with comparable disease.

Limitations

Study results suggested a fluid adaptation process to advanced cancer that can be influenced by multiple individual and disease factors. A larger sample size should provide the needed power to detect these trends with more confidence. Also, future work should control for the effects of symptom burden and the varied prognosis trajectories associated with different tumor types. For example, breast and prostate cancer share a longer prognostic trajectory than lung or ovarian cancer. These disease characteristics may have a meaningful impact on patients’ adaptation to advanced cancer and should be accounted for.

Conclusions

A diagnosis of advanced cancer requires a comprehensive coping response and continued adjustment to a now shortened life span (Reynolds, 2008). A person’s physical health is sorely compromised in these cases, but patients’ emotional health can be robustly supported and even improved (Jim & Jacobsen, 2008; O’Brien & Moorey, 2010; Rajandram, Jenewein, McGrath, & Zwahlen, 2011). Predicting those factors that mitigate cancer related distress is an important research task with meaningful implications for cancer practice. Two factors investigated here, age and recurrence status, suggest differential coping experiences for patients. Data support the idea that recurrent cancer presents a unique challenge for middle aged patients. These patients may benefit from tailored interventions that help them adjust specifically to the recurrence with emphasis on identifying ways to maintain participation in life events. Planning treatment or expected fatigue around everyday events such as childrens’ activities or work hours may allow these people to transition to living with cancer or “reclaim” meaningful aspects of their lives after a period of treatment (Nissim et al., 2012). In either case, patients and their families may be able to retain some normalcy and mitigate the effects of the illness experience.

These findings also have implications for applied research in oncologist-patient communication. Advocated core communication skills in oncology include discussing prognosis, responding to difficult emotions, and running a family meeting. Tailoring these communication skills to patients’ age and recurrence status may enhance patient adaptation as well as clinician self efficacy. (Kissane et al., 2012) All in all, adaptation to advanced cancer is a dynamic process that may differ in accordance with age-related or illness factors. These results suggest that it is important to monitor patients’ emotional health over the early months following their diagnosis, keeping keen attention on middle aged patients with recurrence, who are most likely to face unremitting emotional challenges in the face of their diagnosis and be in need of additional or targeted support.

Funding sources:

NCI P-30, 2009–2010 Case Comprehensive Cancer Center; NCI/NIA R01CA10282: PI: Rose

References

- Andersen BL, Shapiro CL, Farrar WB, Crespin T, & Wells-DiGregorio S (2005). Psychological responses to cancer recurrence: A controlled prospective study. American Cancer Society, 104(7), 1540–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arden-Close E, Gidron Y, & Moss-Morris R (2008). Psychological distress and its correlates in ovarian cancer: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 17(11), 1061–1072. doi: 10.1002/pon.1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes MM, & Carstensen LL (1996). The process of successful aging. Aging & Society, 16(4), 397–423. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, & Baltes MM (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: the model of selective optimization with compensation. In Baltes PB & Baltes MM (Eds.), Successful aging: perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 1–34): Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England and New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Beadle GF, Yates PM, Najman JM, Clavarino A, Thomson D, Williams G, & et al. (2004). Beliefs and practices of patients with advanced cancer: Implications for communication. British Journal of Cancer, 91, 254–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L, Isaacowitz D, & Charles S (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, & Nesselroade J (2000). Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 79(4), 644–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella DF, Jacobsen PB, Orav EJ, Holland JC, Silberfarb PM, & Rafla S (1987). A brief POMS measure of distress for cancer patients. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40, 939–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella DF, Mahon SM, & Donovan MI (1990). Cancer recurrence as a traumatic event. Behavioral Medicine, 16(1), 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson M, Rompei P, & Ales K, et al. (1987). A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in logitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40, 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg L, Reichman M, Miller B, Hankey B, Singh G, Lin Y, … Edwards B (2009). Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: Selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes & Control, 20(4), 417–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, & Studts JL (1995). Short-form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric information. Psychological Assessment, 7(1), 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ersner-Hershfield H, Mikels JA, Sullivan SJ, & Carstensen LL (2008). Poignancy: Mixed Emotional Experience in the Face of Meaningful Endings. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 94(1), 158–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum G (1988). Multidimensional functional assessment of older adults. The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services Procedures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Pimley S, & Novacek J (1987). Age differences in stress and coping processes. Psychology & Aging, 2(2), 171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldzweig G, Andritsch E, Hubert A, Walach N, Perry S, Brenner B, & Baider L (2009). How relvant is marital status and gender variables in coping with colorectal cancer: A sample of middle-aged and older cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 18(8), 866–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell D, Fitch MI, & Deane KA (2003). Women’s experiences with recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Nursing, 26(1), 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert-Williams N, Neal R, Morrison V, Hood K, & Wilkinson C (2011). Anxiety, depression and quality of life after cancer diagnosis: What psychosocial variables best predict how patients adjust. Psycho-Oncology. doi: 10.1002/pon.1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husson O, Mols F, & Van de Poll-Franse LV (2011). The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: A systematic review. Annals of Oncology, 22, 761–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins PL, May VE, & Hughes LE (1991). Psychological morbidity associated with local recurrence of breast cancer. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 21(2), 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jim HS, & Andersen BL (2007). Meaning in life mediates the relationship between social and physical functioning and distress in cancer survivors. British Journal of Health Psychology, 12, 363–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jim HS, & Jacobsen PB (2008). Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth in cancer survivorship: A review. Cancer Journal, 14, 414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jim HS, Richardson SA, Golden-Kreutz DM, & Andersen BL (2006). Strategies used in coping with a cancer diagnosis predict meaning in life for survivors. Health Psychology, 25(6), 753–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford A, Moskowitz R, Jackson B, & Jaffe M (1963). Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA, 185, 914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenne Sarenmalm E, Öhlén J, Odén A, & Gaston-Johansson F (2008). Experience and predictors of symptoms, distress and health-related quality of life over time in postmenopausal women with recurrent breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 17(5), 497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissane D, Bylund C, Benerjee S, Bialer P, Levin T, Maloney E, & D’Agostino T (2012). Communication skills training for oncology professionals. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(11), 1242–1247. Retrieved from http://jco.ascopubs.org/ website: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb DA, Boyatzis RE, & Mainemelis C (2001). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. In Sternberg RJ & Zhang L (Eds.), Perspectives on thinking, learning, & cognitive styles (pp. 227–247). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lamerato L, Havstad S, Gandhi S, Jones D, & Nathanson D (2006). Economic burden associated with breast cancer recurrence. Cancer, 106(9), 1875–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockenhoff C, & Carstensen L (2004). Socioemotional selectivity theory, aging, and health: The increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. Journal of Personality, 72, 1395–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockenhoff C, & Carstensen L (2008). Decision strategies in health care choices for self and others: older but not younger adults make adjustments for the age of the decision target. Jounal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 63(2), 106–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon SM, & Casperson DS (1995). Psychosocial concerns associated with recurrent cancer. Cancer Practice, 3(6), 372–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCorkle R, & Young K (1978). Development of a symptom distress scale. Cancer Nursing, 1(5), 373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, & Droppleman LF (1992). Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service. [Google Scholar]

- Miovic M, & Block S (2007). Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer, 110(8), 1665–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor V (1987). Cancer patients quality of life over the disease course: Lessons from the real world. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40(6), 535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor V (1992). QOL measurement scale for cancer patients: Differentiating effects of age from effects of illness. Oncology, 6(2 Suppl), 146–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor V, Allen S, & Malin M (1994). The psychosocial impact of cancer on older versus younger patients and their families. Cancer, 74(7 Suppl), 2118–2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton TA, & Duck JM (2001). Communication and health beliefs: Mass and interpersonal influence on perceptions of risk to self and others. Communication Research, 28(5), 602–626. [Google Scholar]

- Munkres A, Obsert MT, & Hughes SH (1992). Appraisal of illness, symptom distress, self-care burden, and mood states in patients receiving chemotherapy for initial and recurrent cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 19, 1201–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen M, & Muthen L (2000). Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 24, 882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCI. (2010). When Cancer Returns. (10–2709). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Knapp JE, & Schulz R (1996). Longitudinal analysis of specific domains on internal control and depressive symptoms in patients with recurrent cancer. Health Psychology, 15(5), 323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissim R, Rennie D, Fleming S, Hales S, Gagliese L, & Rodin G (2012). Goals set in the land of the Living/Dying: A longitudinal study of patients living with advanced cancer. Death Studies, 36, 360–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CW, & Moorey S (2010). Outlook and adaptation in advanced cancer: A review. Psycho-Oncology, 19, 1239–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura M, Yamawaki S, Akechi T, Taniguchi K, & Uchitomi Y (2005). Psychiatric disorders following breast cancer recurrence: Prevalence, associated factors and relationship to quality of life. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 35(6), 302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano Y, Okamura H, Watanabe T, Narabayashi M, Katsumata N, Ando M, Adachi I, Kazuma K, Akechi T & Uchitomi Y (2001). Mental adjustment to first recurrence and correlated factors in patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research & Treatment, 67, 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker P, Baile W, De Moor C, & Cohen L (2003). Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 12, 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LH, Henry JD, Hosie JA, & Milne AB (2006). Age, anger regulation and well-being. Aging & Mental Health, 10(3), 250–256. doi: 10.1080/13607860500310385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radziewicz R, Rose JH, Bowman KF, Lewis S, & O’Toole EE (2009). Problems raised by patients during the early treatment phase for late-stage cancer. Psycho-Oncology,18, S75. [Google Scholar]

- Rajandram RK, Jenewein J, McGrath C, & Zwahlen RA (2011). Copin processes relevant to posttraumatic growth: An evidence-based review. Supportive Care Cancer, 19, 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds MAH (2008). Hope in adults, ages 20–59, with advanced stage cancer. Palliative & Supportive Care, 6, 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J (1993). Interactions between patients and providers: An exploratory study of age differences in emotional support. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 11(2), 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rose J, O’Toole E, Einstadter D, Love T, Shenko C, & Dawson N (2008). Patient age, well-being, perspectives, and care practices in the early treatment phase for late-stage cancer. Journal of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences, 63A(9), 960–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J, O’Toole E, Dawson N, Lawrence R, Gurley D, Thomas C, Hamel MB, & Cohen HJ (2004). Perspectives, preferences, care practices, and outcomes among older and middle-aged patients with late-stage cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22(24), 4907–4917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JH, Bowman KF, Radziewicz RM, Lewis SA, & O’Toole EE (2009). Predictors of Engagement in a Coping and Communication Support Intervention for Older Patients with Advanced Cancer. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, s296–s299. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02517.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JH, Radziewicz R, Bowman KF, & O’Toole EE (2008). A coping and communication support intervention tailored to older patients diagnosed with late-stage cancer. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 3(1), 77–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvo N, Zeng L, Zhang M, Leung M, Khan L, Presutti R, Nguyen J, Holden S, Culleton S, Chow E (2012). Frequency of reporting and predictive factors for anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Clinical Oncology, 24, 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, & Yucel R (2002). Computational strategies for multivariate linear mixed-effects models with missing values. J Computat Graph Stats, 11, 437–457. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S (1999). Age and anger. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 40(3), 273–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Williamson GM, Knapp JE, Bookwala J, Lave J, & Fello M (1995). The psychological, social, and economic impact of illness among patients with recurrent cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 13(3), 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Silliman RA, Dukes KA, Sullivan LM, & Kaplan SH (1998). Breast cancer care in older women: Sources of information, social support, and emotional health outcomes. Cancer, 83(4), 706–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer R, Nilsson B, Wright A, Pirl W, & Prigerson H (2010). Anxiety disorders in advanced cancer: Correlates and predictors of end of life outcomes. Cancer. Retrieved from doi: 10.1002/cncr.24954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, & Huggins ME (2002). The first year after breast cancer diagnosis: hope and coping strategies as predictors of adjustment. Psycho-Oncology, 11(2), 93–102. doi: 10.1002/pon.574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata 9 [Computer software]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP [Google Scholar]

- Step MM, & Ray EB (2011). Patient perceptions of oncologist-patient communication about prognosis: Changes from initial diagnosis to cancer recurrence. Health Communication, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.527621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomich P, & Helgeson V (2006). Cognitive adaptation theory and breast cancer recurrence: Are there limits. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Levenson RW, & Carstensen LL (2000). Autonomic, subjective, and expressive responses to emotional films in older and younger Chinese Americans and European Americans. Psychology and Aging, 15(4), 684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivar CG, Canga N, Canga AD, & Arantzamendi M (2009). The psychosocial impact of recurrence on cancer survivors and family members: a narrative review. J Adv Nurs, 65(4), 724–736. doi: 1365–2648.2008.04939.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren M (2009). Metastatic breast cancer recurrence: A literature review of themes and issues arising from diagnosis. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 15, 222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman AD, & Worden JW (1986). The emotional impact of recurrent cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 3(4), 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Worden JW (1989). The experience of recurrent cancer. CA: Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 39(5), 305–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H-C, Brothers BM, & Andersen BL (2008). Stress and quality of life in breast cancer recurrence: moderation or mediation of coping? Annals Of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication Of The Society Of Behavioral Medicine, 35(2), 188–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H-C, Thornton LM, Shapiro CL, & Andersen BL (2008). Surviving recurrence: psychological and quality-of-life recovery. Cancer, 112(5), 1178–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann C, Burman D, Swami N, Krzyzanowska MK, Leighl N, Moore M, … Tannock I (2010). Determinants of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer, 19(5), 621–629. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]