Abstract

Task sets have been argued to play an important role in cognition, giving rise to the notions of needing to switch between active task sets and to control competing task sets in selective attention tasks. For example, it has been argued that Stroop interference results from two categories of conflict: informational and task (set) conflict. Informational conflict arises from processing the word and is resolved by a late selection mechanism; task conflict arises when two task sets (i.e., word reading and colour identification) compete for activation and can be construed as involving an early selection mechanism. However, recent work has argued that task set control might not be needed to explain all of the switching cost in task switching studies. Here we consider whether task conflict plays a role in selective attention tasks. In particular, we consider whether S-R associations, which lead to informational conflict, are enough on their own to explain findings attributed to task set conflict. We review and critically evaluate both the findings that provided the original impetus for proposing task conflict in selective attention tasks and more recent findings reporting negative facilitation (longer RTs to congruent than to neutral stimuli) – a unique marker of task conflict. We then provide a tentative alternative account of negative facilitation based on poor control over informational conflict and apply it to a number of paradigms including the Colour-Object interference and Affordances tasks. It is argued that invoking competition between task sets in selective attention tasks might not be necessary.

Keywords: task sets, Stroop task, interference, task conflict, phonological processing

A task set has been defined as a collection of control settings or task parameters that program the system to perform processes such as stimulus identification, response selection, and response execution (Vandierendonck, Liefooghe, & Verbruggen, 2010). Said differently, to adopt a task-set is to select, link, and configure the elements of a chain of processes that will accomplish a task (Rogers & Monsell, 1995). Task sets and their control have been argued to play an important role in cognition, giving rise to the notions of needing to switch between two or more intentionally activated task sets in task switching tasks (Monsell, 2003; Rogers & Monsell, 1995) and needing to control conflict between an intentionally activated task set and a competing, exogenously activated, irrelevant task set in selective attention tasks (known as task conflict; Goldfarb & Henik, 2007; Kalanthroff et al., 2018; Monsell, Taylor & Murphy, 2001; Parris et al., 2022).

Recently, however, the extent to which task sets and their control determine cognitive performance has been questioned. In the context of task switching, processing costs that were previously attributed to controlled switching between active task sets, have been accounted for with reference to feature-integration biases (see Schmidt, Liefooghe & DeHouwer, 2020). In parallel, several recent accounts have questioned the attribution of behavioural effects in selective attention tasks to cognitive control (Algom, Fitousi, & Chajut, 2022; Algom & Chajut, 2019; Schmidt, 2019), again questioning the need for cognitive control in cognition. Such arguments also pose a challenge to the foundational basis of the notion of task set competition and control in tasks of selective attention, especially given that the competing task set is exogenously, and not intentionally, activated in selective attention tasks.

We, amongst others, have been strong proponents of task conflict as a contributor to Stroop task performance and selective attention more generally (Augustinova et al., 2018; Augustinova, Ferrand & Parris, 2019; Ferrand et al., 2020; Parris 2014; see in particular Parris et al., 2022). Responses to Schmidt et al.’s (2020) model have also pointed out that feature-integration approaches fail to account for preparation effects in task switching studies, one of the key pieces of evidence for task set control in cognition (Monsell & McLaren, 2020; see also Koch & Lavric, 2020). Nevertheless, these recent developments in the wider fields of task set switching (Schmidt et al., 2020) and cognitive control (Algom et al., 2022; Algom & Chajut, 2019; Schmidt, 2019), and our own endeavours in questioning the evidence for the presence of conflict at other levels of processing (Burca et al., 2021; 2022; Hasshim & Parris; 2014; 2015; 2018; Parris et al., 2022), prompted us to reassess the role that task conflict and its control play in selective attention paradigms.

To be clear, our aim is not to argue that task sets do not play a role in selective attention tasks. The intentional, goal-oriented task set of colour naming seems to be a pre-requisite to achieve the instructed goal of naming the colour of the font in the Stroop task. Without it, what would participants do on presentation of this unusual stimulus? They would ignore the font colour and likely read the word – or they would just get up out of their chair and walk away. Our aim is not therefore to question the functional role of intentionally activated task sets, but is instead to question the role of exogenously activated task sets in selective attention tasks. Among the questions that could be asked regarding the exogenously activated task set is which task set becomes activated? Since most objects afford a number of tasks (e.g., a word can be read, categorised, defined, counted) which task set is exogenously activated when that object is presented? In the context of task switching, it seems reasonable to assume that it is the most recently activated task set, which is defined by the experimental context. But in selective attention tasks it is not so clear. Moreover, it is not clear what properties of an irrelevant stimulus activate a task set. Proponents of task set conflict in selective attention tasks would argue that it is “word-likeness” that exogenously activates the task set for reading but it is unclear what properties define word-likeness, nor is it clear when this happens and whether S-R associations without a task set guiding them such as orthographic to phonological connections or phonology to phonetic code connections are themselves enough to account for the effects observed without resorting to the notion of the whole task set for word reading (or whole set of S-R associations) being activated in advance of their execution.

We aim to go beyond recent reviews of task conflict (Littman, Keha, & Kalanthroff, 2019; Parris et al., 2022) by taking a broader and more critical look at the role of exogenously activated task sets. Moreover, in order to buttress our critical evaluation, we aimed to provide a tentative alternative account of the data – one based on established S-R associations that provide words with privileged access to word forms, and one that draws on some of the weaknesses of current task conflict theory – to highlight the notion that other accounts of the data are at least feasible. Indeed, in our recent review of levels of conflict and facilitation in the Stroop task (Parris et al., 2022), we concluded that whilst there was strong evidence in favour of the notion of task conflict in the Stroop task, more work was needed to identify what triggers activation of the task set for word reading and how other types of conflict, particularly phonological conflict, might interact with task conflict. We take this as our starting point but, for the purposes of testing the task conflict framework, go further by adopting the perspective that S-R associations can account for all effects attributed to task conflict. Whilst we focus here mainly on the Stroop task (Stroop, 1935) – since, to date, this is where most of the work on the role of task conflict in selective attention has been done – recent investigations have provided evidence for the influence of task conflict in other selective attention paradigms (e.g., the Affordances Task – see Littman & Kalanthroff, 2020; 2022) and thus, we also evaluate the evidence for task conflict in these paradigms. Our endeavour is therefore relevant to the wider field of selective attention and cognitive control.

Distinguishing Task conflict from Informational conflict

Here we follow Rogers and Monsell (1995) in accepting that defining what constitutes a ‘task’, is, to use a common phrase that serves to highlight the point being made, a ‘difficult task’. We will therefore jump right past this definitional problem and “leave this conceptual boundary cloudy” (Rogers & Monsell, 1995: 208) without fear that doing so will impede our aims and objectives.

We can however offer a definition of task conflict. For task conflict to occur, at least two task sets must compete for activation. Given our definition of a task set above, this means that the entire collection of control settings/task parameters that program the system to perform one task (e.g., word reading consisting of visual analysis, letter/grapheme identification, lexical identification (semantic processing), phonological processing) would compete for activation with the entire collection of control settings that program the system to perform another task (e.g., classify a colour consisting of visual analysis, colour identification, semantic processing, phonetic encoding). The idea is that “whole task sets compete, over and above any competition between specific responses associated with a stimulus” (Monsell et al., 2001: 139–140). That is, over and above any S-R associations. In the context of the Stroop task, “task conflict” has been evidenced in three main ways: 1) Anterior cingulate activation on congruent trials (MacLeod & McDonald, 2000); 2) slower responses to neutral words (e.g., the word ‘house’) than to non-lexical (i.e., non-pronounceable) stimuli (e.g., ‘xxxx’; see Augustinova, Parris & Ferrand, 2019); 3) slower responses to congruent stimuli than to non-lexical stimuli, also known as reverse or negative facilitation (e.g., Goldfarb & Henik, 2007).

Representations that are activated by S-R associations (e.g., grapheme-to-phoneme conversion; or, for an irregular word, the whole orthographic form and the whole phonological form), and the representations/outputs produced by task sets (e.g., the name of a colour), can be described as information. Information derived from processing one stimulus, or one dimension of a stimulus (e.g., semantic information), can compete with information derived from processing another stimulus or another dimension of the same stimulus; this is called informational conflict. Thus, task conflict can be distinguished from the conflict that arises from the information that results from the operation of task sets or from S-R associations. Therefore, conflict between task sets cannot be phonological conflict, since phonological or phonetic (word form) representations are outputs and not whole task sets.1 Likewise, task set conflict is also not equivalent to the semantic conflict that might occur due to both the colour and the word dimensions of colour-word Stroop stimuli being processed at the semantic level. Neither is task set conflict response conflict, which results from the activation of potential response options given the prior information accrued from earlier processing of both dimensions of the Stroop stimulus. In short, under the task conflict framework, task conflict is independent of informational conflict, although informational conflict would not be entirely independent of task conflict given that some information is assumed to result from the operation of task sets. Clearly, it would be helpful for the purposes of distinction that, given its theorised independence, task conflict could be measured using a unique performance marker. Task conflict theorists have provided one such measure in the form of reverse or negative facilitation – the finding that congruent trial RTs can be longer than a neutral, non-lexical baseline (e.g., xxxx) in conditions described as a low task conflict control context. One aim of the present paper is to provide a tentative alternative account of negative facilitation; one that does not rely on invoking competition between task sets. In our alternative account, we consider whether negative facilitation could result purely from the notion that words have privileged access to word forms via strong S-R associations (e.g., Mahon, Costa, Peterson, Vargas & Caramazza, 2007; Roelofs, 2003).

Outline of the paper

In the present paper, we set out to provide a reassessment of the task conflict framework as applied to selective attention tasks. Importantly, our aim was not to unequivocally argue that task conflict does not occur; it was instead to highlight current limitations of the account and to assess how much can be explained without it. To achieve this aim, we will: 1) describe and evaluate the studies and findings that provided the initial impetus for suggesting the influence of task conflict in selective attention tasks; 2) review the evidence for the more recent phenomenon of negative facilitation (congruent > non-lexical neutral), purportedly a unique marker of task conflict; 3) describe what we see as current challenges to the task conflict framework; 4) provide a tentative, alternative, and testable account of negative facilitation based on the notion of reduced control over S-R associations that results from certain experimental contexts; 5) discuss negative facilitation in the context of other selective attention tasks and how the alternative account might explain findings in those contexts.

1. Task and Informational conflict in the Stroop task

The Stroop task requires participants to focus on one dimension of a stimulus, the colour dimension, whilst ignoring another dimension, the word dimension. The task produces the Stroop interference effect – referring to the fact that identifying the colour that a word is printed in takes longer when the word denotes a different colour (colour-incongruent trials; e.g., the word red displayed in blue font) compared to a baseline condition (colour-neutral trials; e.g., the word top displayed in blue font). In addition, words that are congruent with the colour (colour-congruent trials; e.g., the word red in red font) result in faster colour-identification times when compared to a neutral baseline condition, producing Stroop facilitation effect (Dalrymple-Alford, 1972; Dalrymple-Alford & Budayr, 1966; Hasshim & Parris, 2021; see also MacLeod, 1991, for a review).

The extent to which the information generated from the irrelevant dimension (e.g., phonological, semantic and response information) differs from that generated from the relevant dimension was thought to determine the degree of Stroop interference that is subsequently observed (Klein, 1964). When considering the standard incongruent Stroop trial where the word dimension is a colour word that is incongruent with the target colour dimension that is being named (e.g., red in blue), and where the colour red is also a potential response, one might surmise numerous levels of representation where information from these two dimensions might compete. Processing of the colour dimension of a Stroop stimulus in order to name the colour would, on a simple analysis, require initial visual processing to establish colour identification, followed by activation of the relevant semantic representation and then word-form (phonetic) encoding of the colour name in preparation for a response. For this process to advance unimpeded until response there would need to be no competing representations activated at any of those stages.

Like colour naming, the processes of word reading also requires visual processing but of letters and not of colours. Word reading also requires the computation of phonology from orthography which colour processing does not. Despite being a task in which participants do not intend to engage, stimulus-response (S-R) associations mean irrelevant words are obligatorily processed (Monsell et al., 2001). Until recently, the evidence for conflict at the level of semantics was confounded (Parris et al., 2022). However, there is now good evidence for competition at the level of semantics (Burca et al., 2021; 2022). Likewise, obligatory phonological processing leads to obligatory phonetic encoding giving rise to competition between word form representations (Coltheart et al., 1999; Marmurek, Proctor & Javor, 2006; Parris et al., 2019). Finally, since both dimensions give evidence towards different responses, there is competition at the level of the response effectors (e.g., actual pronunciation with a vocal response Stroop task and finger selection with a manual button-press response). Importantly there is evidence that even when participants respond with a manual response the irrelevant word is pronounced sub-vocally (e.g., Parris et al., 2019).

For most of their history, Stroop interference and facilitation were thought to result from the information conveyed by the irrelevant word dimension that competed with that computed from the target dimension at late selection stages. However, the introduction of the notion of task conflict (Goldfarb & Henik, 2007; MacLeod & MacDonald, 2000; Monsell et al., 2001) changed that perspective indicating an earlier selection mechanism that controlled activation of the whole task set of word reading even before information was generated from that word. Motivated by the finding that the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, i.e., a neural structure thought to be involved in monitoring for conflict; Botvinick et al., 2001), had been reported to be more activated by colour-congruent (and colour-incongruent) stimuli than a non-lexical neutral condition (e.g., Bench et al., 1993), MacLeod and MacDonald (2000) argued that the ACC activity represented the need to direct attention away from words irrespective of their congruency status, producing a form of interference present even on colour-congruent trials.

It was Monsell and colleagues (2001) however who were the first to attribute some of the interference in the Stroop task directly to task conflict. They argued that if Stroop interference resulted purely from informational conflict, it should be greater for irrelevant non-colour related words that have stronger connections to their associated lexical information (Cohen, Dunbar & McClelland, 1990; e.g., high frequency words), since their associated information would be accessed more readily. In other words, the word forms of high frequency words would be activated more quickly and would delay the production of the word form of the colour name when compared to low-frequency words. Or real words should be coloured named more slowly than pronounceable non-words. In their influential study Monsell and colleagues reported that interference was not larger for items that are more efficiently read (e.g., high vs. low frequency words, neutral words vs. pseudowords) and concluded that informational conflict (i.e., response conflict) is unable to account for the finding of largely undifferentiated interference produced by these colour-neutral Stroop items. Their results were inconsistent with predictions from Cohen et al. (1990) and, indeed, Monsell et al. actually reported that, if anything, colour naming times were slower for low frequency, not high frequency, items in their experiments.

Given the evidence for a role for task sets in cognitive processing (Monsell, 2003; Rogers & Monsell, 1995), Monsell et al. (2001) argued that their findings were best explained as resulting from competition between task sets; the endogenously activated task set for colour naming and the exogenously activated task set for word reading. This unintentionally activated word reading task set, competes with the intentionally activated colour identification task set, creating task conflict. Thus, they argued that, in addition to informational conflict, Stroop effects derive from task conflict. Monsell et al. suggested that the construct of task set selection could be construed as an “early selection” mechanism that filters irrelevant information. In support of this, see Hershman & Henik (2019; 2020) for pupillometric evidence for task conflict occurring earlier in the response time distribution than informational conflict in the Stroop task (although see below for an alternative interpretation).

Task conflict has been argued to be present in the Stroop task whenever an orthographically plausible letter string is presented (e.g., the word table leads to interference, as does the non-word but pronounceable letter string fanit; the letter string xxxxx less so; Levin & Tzelgov, 2016; Monsell et al., 2001). Accordingly, Monsell et al. suggested that the word reading task set is exogenously activated by properties of a stimulus that make it word-like such as patterns of consonants and vowels arranged in an orthographic structure (Taft, 1979; 1987) or by pronounceability, activated by sub-lexical orthographic to phonological connections.

Both MacLeod and MacDonald (2000) and Monsell et al. (2001)’s arguments provided the foundational bases for subsequent research into task conflict in the Stroop task. However, recent investigations invite a reconsideration of their interpretations of the findings. Stroop task performance has been shown to be unaffected following damage to dorsal ACC (Fellows & Farah, 2005). Furthermore, ACC activity has been argued to be dependent on the trial types (e.g., incongruent, congruent, repeated letter string) being presented intermixed in the same block; when presented in pure bocks (i.e., just incongruent trials), ACC activity does not differentiate between trial types (Floden, Vallesi & Stuss, 2011; see also Parris et al., 2019). Notably, two of the three studies cited by MacLeod and MacDonald as evidencing ACC activity on congruent trials (e.g., Carter, Mintun & Cohen, 1995; Milham et al., 2002; but see Bench et al., 1993) intermixed congruent and neutral trials, indicating that ACC activation is not necessarily a result of conflict on single Stroop trials but represents some other factor that is present when trial types are mixed.

In findings that also encourage a reinterpretation of one of the original motivations for task conflict, there is now ample evidence that Stroop interference is related to item naming efficiency, but where words that are named more slowly are also colour-named more slowly (Algom, Chajut & Lev, 2004; Burt, 1994; Burt, 1999; Burt, 2002). Whilst Monsell et al. were hesitant to make much of their finding showing that low frequency words were colour named more slowly than high-frequency words (because the effect was “small, its reliability was marginal”, p148), the effect has subsequently been repeatedly reported in the literature indicating that much more should be made of it (Burt, 1994; Burt, 1999; Burt, 2002; Dewhurst & Barry, 2006; Levin & Tzelgov, 2016; Navarrete et al., 2015). It is also notable that this effect has been replicated in the picture-word interference task, with pictures presented with low frequency distractors named slower than those with high frequency distractors (Miozzo & Caramazza, 2003; Dhooge & Hartsuiker, 2010).

These findings suggest that in Stroop-like tasks, target naming does not happen until the word is processed, representing a complete failure of selective attention in the context of the neutral-word Stroop task. This is then indicative of an irrelevant word form (i.e., the word name) interfering with the production of the relevant word form (i.e., colour name), representing a competition between responses, even if the irrelevant response is not a valid response for the task. Moreover, the finding indicates that the complete phonological or orthographic code is required before colour naming can occur. Thus, for neutral, non-colour related irrelevant words the extent to which lexical processing interferes in responding to the relevant colour dimension is directly influenced by word processing efficiency (e.g., attributes such as frequency, readability, pronounceability).

Monsell et al. proffered an explanation for the frequency effect, stating that it might result from the occasional “breakthrough” of the word when words are sufficiently primed and participants therefore fail to suppress the word reading task set. This would then create competition at the response selection stage resulting in the need for the conflict to be dealt with. This occasional generation of an inappropriate response would happen more quickly for high-frequency words and be sooner dealt with, resulting in short RTs for high-frequency words. However, an alternative account exists that does not rely on the occasional breakthrough argument, nor on the early selective filtering role of task set selection.

Under the Response Exclusion Hypothesis (Mahon et al., 2007) irrelevant words get obligatorily processed right up to the point of a representation entering an articulatory buffer; no selection occurs before this very late point in processing and selection does not involve selection by competition. Under this account words have privileged access to the articulators; thus, as with Roelofs (2003) and Glaser and Glaser (1989) this model is based on architectural differences between word reading/naming and colour naming. They describe this privileged access as being based on the “quasi rule-like relationship between orthography and phonology” (p. 524; Mahon et al., 2007) and as such results in a “production-ready” representation for the articulators to produce. The response exclusion hypothesis uniquely predicts that low frequency words should interfere more than high frequency words, a finding that theories, based on connectionist architecture (Cohen et al., 1990), find difficult to explain. Under this account frequency effects arise because of the principle that the earlier the response to the distractor enters the articulatory buffer, the earlier it can be removed from the buffer. Since low frequency words would take longer to reach the buffer, it takes longer to remove them from the buffer and thus colour naming times would be slowed. Thus, whilst they differ in their positions about the loci/locus and mechanism of selection, both Monsell et al. and Mahon et al. argue that slower responses for low frequency irrelevant words result from the fact that information about low frequency items take longer to be generated and to be later dealt with.

In our alternative account, we will argue that obligatory word form (phonetic) encoding of pronounceable letter strings (resulting from strong S-R associations (accrued from when children start to learn to read; Roelofs, 2003) that ultimately lead to words having privileged access to pronunciations) leads to interference from pronounceable letter strings due to the delaying of the retrieval of the pronunciation of the target colour name. This delay would not occur for letter strings such as xxxx because they are not pronounceable, but would occur for congruent words thereby producing negative facilitation (congruent RTs > non-lexical neutral RTs) in certain contexts (see below for an account of why any positive facilitation from congruent words does not counteract negative facilitation). In contrast to task set selection, this is a late selection mechanism. Moreover, it will be argued that this obligatory encoding is made more influential by experimental manipulations, purportedly used to induce task conflict, but that actually result in less control over informational conflict – the phonological and phonetic encoding of the irrelevant word – making it harder to inhibit, and that prevent positive facilitation. Thus, it is the combination of poorer control over informational conflict, and the non-pronounceable nature of the baseline (e.g., xxxx), that produces negative facilitation. We will argue that this occurs even with manual-response Stroop tasks for which phonological processing is reduced compared to vocal response Stroop tasks and with which most of the effects of negative facilitation have been reported.

2. The Stroop task and Negative Facilitation – the prime behavioural marker of task conflict

2.1. Task conflict in a mostly non-lexical trial context

As already mentioned, a common finding in the Stroop literature is that colour-identification is faster for colour-congruent than for neutral non-lexical stimuli (Brown, 2011; Entel et al., 2015; see also Augustinova et al., 2019; Levin & Tzelgov, 2016, Shichel & Tzelgov, 2018) – also known as positive facilitation. If, according to task conflict approach, congruent trials involve task conflict but non-lexical stimuli do not (see MacLeod & MacDonald, 2000; Monsell et al., 2001 discussed above), why is negative facilitation (i.e., slower responses to congruent trials compared to non-linguistic baselines) not the more common finding? Task conflict theorists argue that positive facilitation is expressed only when sufficient task conflict control is activated.

Goldfarb and Henik (2007) reasoned that negative facilitation is often not observed when comparing congruent and non-lexical trial RTs because there is a sufficiently large enough proportion of lexical stimuli to activate task conflict control. In other words, constant exposure to real words puts the task conflict controller on high alert, ensuring that it is active, and that task conflict is kept low. The activation of task conflict control means that positive facilitation, representing a lack of another form of control over informational processing, is expressed in the RT data. Increasing the proportion of non-lexical neutral trials (e.g., repeated letter strings) would create the expectation for a low task conflict context thereby reducing task conflict control, resulting in task conflict’s unique behavioural expression – negative facilitation. Thus, Goldfarb and Henik (2007) introduced the notion of a task conflict controller that forms part of a system of cognitive control that is deployed to reduce or prevent task conflict (see also Kalanthroff et al., 2018; and Littman et al., 2019, for a mini review).

In line with this reasoning, Goldfarb and Henik (2007) aimed to reduce task conflict control by increasing the proportion of non-word neutral trials (repeated letter strings) to 75% (see also Kalanthroff et al., 2013a). Additionally, on half of the trials, the participants received cues that indicated whether the following stimulus would be a non-word or a colour word, giving another indication as to whether the mechanisms that control task conflict should be activated. For non-cued trials, when task conflict is high, RTs were slower for congruent trials than for non-lexical trials, producing a negative facilitation effect. Cueing that the upcoming trial involved a congruent or incongruent word led to substantially reduced RTs for both congruent (834ms vs. 942ms) and incongruent (1002ms vs. 1070ms) stimuli and eliminated negative facilitation. Goldfarb and Henik (2007) suggested that previous studies had not detected a negative facilitation effect because resolving task conflict for congruent stimuli when task conflict control is sufficiently active (i.e, when there are ~ 50%+ lexical trials) does not take long, and thus, the effects of positive facilitation were able to be expressed in response times – in other words, positive facilitation had hidden task conflict.

Subsequent work has further clarified the conditions required to observe negative facilitation: Entel and Tzelgov (2018) showed that presenting participants with non-lexical trials and congruent trials (but no incongruent trials) where the portion of the former was 75%, and without presenting cues of any kind, was not enough to reveal negative facilitation. They did however show that this experimental context did result in reduced positive facilitation relative to a mostly congruent block, indicating that a mostly non-lexical block does reduce the capacity of the congruent word to positively facilitate performance. In contrast, a subsequent experiment negative facilitation was reported after pre-exposing participants to a block of incongruent trials prior to completing the mostly non-lexical block and/or when including incongruent trials in a final block. Entel and Tzelgov (2018) explained this by suggesting that task control was not monitored in the first experiment due to the lack of exposure to incongruent trials, which is needed to generate control over the automatic reading process. This line of research suggests in sum that it is not cueing that is key to producing negative facilitation; an interpretation that is supported by the finding of no negative facilitation in Experiment 2 of Goldfarb & Henik (2007) in which non-lexical trials were replaced by neutral word trials but in which cueing was employed). Instead, a combination of mostly non-lexical trials and exposure to informational conflict are important in revealing large negative facilitation effects.

In contrast to the notion that informational conflict is necessary to observe negative facilitation, Kalanthroff et al. (2013a) reported negative facilitation when only non-lexical and congruent trials were included in a block and the stimuli were mostly neutral (i.e., the block only included trials that were free of informational conflict and of the response competition it entails). Unlike Entel and Tzelgov (2018), Kalanthroff et al. (2013a) did employ the same cueing procedure as that used in Goldfarb and Henik’s (2007) study. Again though, negative facilitation was observed in the non-cued block. However, as Entel and Tzelgov noted, Kalanthroff et al. (2013a)’s negative facilitation effect was relatively small (i.e., 15ms vs. the > 70ms reported by Entel and Tzelgov) and the Bayes Factor for the effect was below 3, indicating the evidence was anecdotal. Thus, the cueing context might add something to the production of negative facilitation, but it is the majority non-lexical trial context and exposure to incongruent trials that seems to be largely responsible for observing large negative facilitation effects.

Entel and Tzelgov (2020) followed up their previous work by showing that negative facilitation is not observed if participants’ working memory (WM) resources are taken up by a secondary task. They therefore argued that the expression of negative facilitation requires working memory, arguing that it indicated a role for proactive control. This later result directly contradicts the earlier findings of Kalanthroff et al. (2015) who showed that spare WM capacity prevents negative facilitation, indicating that proactive control plays a role in controlling the expression of task conflict – an idea captured in their computational model of task conflict (Kalanthroff et al., 2018; see here below). Entel and Tzelgov (2020) pointed out that the negative facilitation was again relatively small (i.e., 20 ms) in Kalanthroff et al.’s (2015) study, and that the Bayesian estimate of the support for it was anecdotal (BF10 = 2.48). In contrast, in Entel and Tzelgov’s study negative facilitation was large (~50ms) and was supported by a sensitive Bayes Factor. Thus, in contrast to Kalanthroff et al. (2018)’s model of task conflict (see the following section for description) the most robust evidence is currently consistent with the notion that negative facilitation requires spare working memory resources. However, given the contradictory nature of these findings strong conclusions cannot be drawn at this time regarding the role of working memory in producing negative facilitation.

To sum up, three factors that have been identified that contribute to observing negative facilitation RTs: 1) a mostly non-lexical trial context; 2) anticipation of informational conflict in the form of incongruent trials; 3) spare working memory capacity (Entel & Tzelgov, 2020; but see Kalanthroff et al., 2015; 2018). However, whilst exposure to incongruent trials and working memory capacity seem to play a role in modifying the magnitude of negative facilitation, the two studies investigating the role of working memory have found directly opposing results, and despite being small, significant negative facilitation has been reported without exposure to incongruent trials. Therefore, only the mostly non-lexical trial context and, most importantly, its use as the neutral baseline against which to compare congruent trial RTs, seems to be the sine qua non of significant negative facilitation effects in the studies reported above.

2.2. Negative facilitation without a mostly non-lexical trial context

Despite being important for producing negative facilitation in the above studies, negative facilitation has been reported in the absence of a mostly non-lexical trial context when the Stroop task has been combined with other paradigms. For example, negative facilitation has been reported in studies employing task-switching, the Stop-Signal task and when pupillometry is employed as the dependent variable.

2.2.1. Negative facilitation and task-switching

If negative facilitation reflects task set conflict, it should be greatest when task conflict is at its height. In contrast to selective attention tasks, task switching tasks involve two intentionally activated task sets. For example, when the Stroop task is used in task switching studies, participants are required to switch between reading the word and naming the colour. This would mean that during colour naming trials, the task set for word reading would be more active than it would be in the context of a selective attention task. This would have the effect of increasing the relative conflict between the two task sets.

In two experiments Kalanthroff and Henik (2014) reported that negative facilitation was significant when the time between a cue indicating whether the upcoming task was word reading or colour naming and the appearance of the Stroop stimulus (the cue-target interval or CTI) was 0ms, but was not significant when CTI was 300ms or 1500ms. In other words, negative facilitation was larger when there was less time to prepare for the upcoming task (i.e., when task set competition was greater – similar to the results from Aron et al., 2004). There is also evidence of a relationship between negative facilitation and task-switching in studies that did not employ the Stroop task but did employ a neutral condition against which congruent trials could be compared (e.g., Aarts et al., 2009; Aron et al., 2004; Rogers & Monsell, 1995).

2.2.2. Negative facilitation and the Stop-Signal task

Kalanthroff, Goldfarb and Henik (2013b) have shown that negative facilitation can be observed when the Stroop task is combined with the Stop-Signal Task even in conditions where the proportion of congruent, incongruent and repeated-letter trials are equal. In the Stop-Signal Task participants are asked to respond to particular stimuli (in this case the colour of the font of Stroop stimuli) unless a stop-signal is presented. In two experiments (1 and 3), the authors showed that on trials in which there was no stop signal (go trials), interference and positive facilitation were reported. However, on trials on which a stop-signal was presented but participants responded anyway (i.e., erroneous stop-signal response trials or ESSR), interference and negative facilitation were reported. Negative facilitation was not observed in their Experiment 2 in which the nonword neutrals were replaced with word neutrals. Kalanthroff and colleagues (2013b) argued that their results showed that task conflict and stop-signal inhibition share a common control mechanism, and one that is independent of the control mechanism activated by informational conflict – and this was in a context in which all trial types were presented equally often and when no other task conflict control manipulation was applied.

Kalanthroff et al. (2013b) argued that an ESSR can occur because (a) the primary go process was extremely fast or (b) the inhibitory control was momentarily less efficient and produced slower stopping, but favoured the latter position given that control is an effortful process. The authors also drew on neuroimaging results showing ACC activations on stop-signal trials (Brown & Braver, 2005; van Boxtel, van der Molen, & Jennings, 2005) to argue that the similarity in activations with nonneutral (incongruent and congruent) Stroop stimuli. They argued that negative facilitation is evident on ESSR trials because both task conflict and ESSR trials represent reduced inhibitory control. Furthermore, the authors replicated the finding showing that inhibition of initiated responses on stop trials were less likely and slower on incongruent Stroop trials (Verbruggen, Liefooghe, & Vandierendonck, 2004).

2.2.3. Negative facilitation and pupillometry

Pupillometry has been shown to measure negative facilitation using the difference between colour-neutral words and non-lexical trials even in the absence of negative facilitation in the manual response RT data (Hershman & Henik, 2019; 2020). Using incongruent, congruent and a repeated letter string baseline, but without manipulating the task conflict context in a way that would produce negative facilitation (the proportion of trial types was equal and no cueing as employed), Hershman and Henik observed a standard Stroop interference effect and small non-significant, positive facilitation. However, the authors also recorded pupil dilations during task performance and reported both interference and negative facilitation in this metric (pupils were smaller for the repeated letter string condition than for congruent stimuli). The timeseries data showed that pupil data began to distinguish between the repeated letter string condition and incongruent and congruent conditions up to 500ms before there was divergence between the incongruent and congruent trials.

More recently, Hershman et al. (2021) reported that, in terms of colour naming response times, repeated letter strings did not differ relative to symbol strings (e.g., %&^$), consonant strings (e.g., CGHD) and colour-neutral words (e.g., table). All were responded to more slowly than congruent trials evidencing positive facilitation on congruent trials. However, they also reported that pupil size data revealed larger pupils to congruent trials compared to repeated letter strings, symbol strings, and consonant strings. This effect indicates that a letter string needs to be readable (pronounceable) for the task set for word reading to be activated and for task conflict to arise.

2.3. A model of task conflict

Prior to Entel and Tzelgov’s (2018; 2020) work, Kalanthroff et al. (2018) presented a model of Stroop task performance that successfully incorporates both task conflict and its control. This model is based on processing principles of Cohen and colleagues’ neural network models (Botvinick et al., 2001; Cohen et al., 1990) that describe the processing of stimuli as occurring via activation of a series of modules along two processing pathways – a word processing pathway and a colour processing pathway – with the possibility of each module being activated by each pathway simultaneously. When different pathways activate a common module in the output layer, this results in facilitation or interference depending on whether pathways activated by the word and colour dimensions are similar or different. For a congruent trial, facilitation results since both word and colour activate the module providing evidence for the same response in the output layer; in contrast, for an incongruent trial the two pathways provide evidence for different responses, resulting in interference. An important component of the model is that the momentary balance of evidence for each response is defined by the strength of evidence in favour of one minus the strength of evidence in favour of the other. When the difference between the two pieces of evidence crosses a threshold, selection occurs. To ensure that the correct response is produced a Task Demand unit biases processing to ensure the colour-processing pathway wins out. Therefore, although the biasing of attention toward a certain pathway (attentional selectivity) begins early in processing, its effect is to reduce competition at the response module to allow for more efficient response (action) selection.

What is unique about Kalanthroff et al. (2018)’s model is the role proactive (intentional, sustained; see Braver, 2012) and reactive control play in modifying task conflict. When proactive control is high, task conflict is low and thus negative facilitation is not present. When proactive control is low, task conflict is high, and an inhibition mechanism then operates to modify the response threshold to all lexical stimuli. Reactive control then operates to control task conflict but is not sufficient to prevent its behavioural manifestation (negative facilitation). This raising of the response threshold would not happen for repeated letter string trials (e.g., xxxx) because the task unit for word reading would not be activated. Since responses for congruent trials would be slowed relative to non-lexical trials, negative facilitation results. In contrast to Botvinick et al.’s (2001) model, reactive control is employed when proactive control is low, not when informational conflict is detected, and since task control can be activated even in the absence of informational conflict, task control is dissociable from informational conflict control (but see Entel & Tzelgov, 2020, who argue task conflict control is dependent on the detection of informational conflict). A further unique aspect of Kalanthroff et al.’s model is that it is able to account for the common finding of larger standard deviations for congruent than for non-lexical neutral trials, a finding that had been considered a weakness of Cohen et al.’s original model (see Mewhort, Braun & Heathcote, 1992). This increased variability was accounted for by task conflict interacting with noise on task demand units; thus, an additional level of conflict permitted the influence of an additional level of noise in the system.

3. Current challenges for the task conflict framework

Negative facilitation serves as a new and unique marker of performance that is independent of those findings. In this section we highlight some of the current challenges to the task conflict framework and its account of negative facilitation.

3.1. Is there a task selection problem?

Monsell et al. (2001) argued that the notion of “task set” is essential in explaining why we do not always name (or translate or classify) attentively fixated words. A written word, they argue, affords many possible tasks and thus the appropriate mental machinery needs to be pre-configured for the intended action to occur and the appropriate output to be produced. Recent research indicates that even for a process often considered ‘automatic’ – visual word recognition – certain aspects of word processing (such as word frequency and word/nonword status) can be delayed or attenuated following a previous non-word reading perceptual task (Elchlepp, Monsell & Lavric, 2021). However, if a fixated written word affords many possible tasks, which task set will be exogenously activated in selective attention tasks? In other words, is there a task selection problem? A task selection problem could lead to the exogenous activation of multiple relevant task sets (depending on recent intentionally activated task sets) resulting in tremendous task set competition. Nonetheless, it is also possible that given the activation of multiple task sets, no one task set is exogenously activated strongly enough to influence task performance; or perhaps, in selective attention tasks, they are not exogenously activated at all. Perhaps it is reasonable to assume that the word reading task set, as the more routinised task set, is the task set that is activated when a letter string is presented. However, why is the entire collection of control settings that program the system to perform reading (whole sets of S-R associations) needed in advance of reading when S-R association proceeding serially are enough for reading to happen.

3.2. Exogenous activation of task sets or just S-R associations?

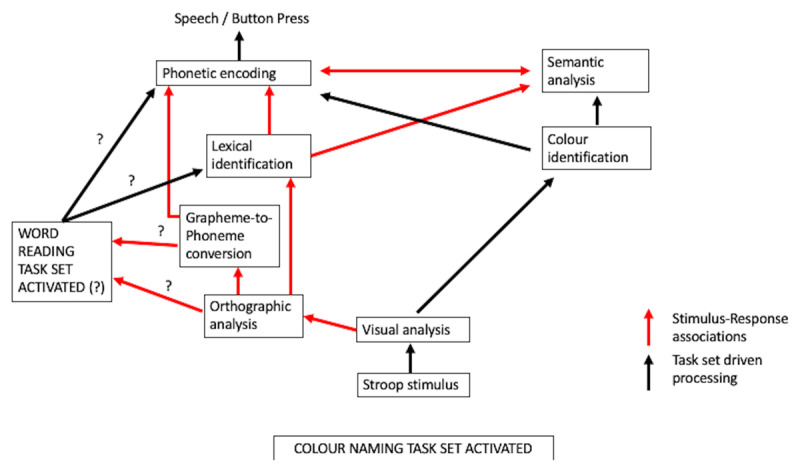

Alongside their novel argument that the Stroop task involves task set conflict, Monsell et al. (2001) noted that interference in the Stroop task also derives from S-R associations that automatically compute grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence rules that lead to response conflict (competition at the level of response output) – and potentially even process the word to the level of semantics in some contexts (e.g., Burca et al., 2021; 2022; Coltheart et al., 2001; Cohen et al., 1990; McClelland, & Rumelhart, 1981). These S-R associations do not need a task set directing their activation because they are themselves activated in response to certain stimuli (the presence of graphemes). Indeed Monsell et al. argued that these associations could be responsible for exogenously activating the task set for word reading given that sub-lexical orthographic to phonological connections give clues to pronounceability or the patterns of consonants and vowels arranged in an orthographic structure that confer word-likeness on a letter string (Taft, 1979; 1987). However, if S-R associations already lead to the processing of the irrelevant word, what is left for the task set for word reading to do (see Figure 1)? Is it that obligatory low-level processes (e.g., orthographic/phonological processing) represent the automatic S-R associations that trigger the task set for word reading (as argued by Levin & Tzelgov, 2016) which then leads activation of the task set for word reading and subsequent semantic and word form (phonetic encoding) processing? In this instance task conflict would influence performance relatively early in the processing stream. Or perhaps the S-R associations accomplish all of the above and the task set for word reading, linking as it does the elements necessary for a response, ensures the final response is guided by outputs from word reading processes. Without the task set for word reading perhaps the S-R associations would have no influence on performance. Another way of asking the same question is whether stimulus-driven behaviour necessitates invocation of exogenous task set activation? Could S-R associations be enough on their own? Do rules and settings need be preloaded to enable certain processes to run their course? And is it that all the to-be-used S-R associations need to be linked up in advance of processing or do they simply follow on one from the other in a serial manner without a guide for action? In the case of intended, planned actions, the notion of a task set aiding some aspects of goal-oriented behaviour, linking or strengthening the links between associated processing seems to have cognitive utility, but one might question whether it is a characteristic of unintended processing.

Figure 1.

Modified version of the model presented in Monsell et al. (2001). What activates the task set for word reading and what does it go on to do? Are S-R associations such as grapheme-to-phoneme processing enough to explain the effects attributed to task conflict? An alternative account of negative facilitation is that strong S-R associations confer privileged access for pronounceable letter strings to their associated phonetic codes meaning that the irrelevant word is obligatorily processed up to the level of phonetic encoding, which delays phonetic encoding of the colour name. The longer the encoding of the irrelevant word takes, the longer the delay. For example, phonetic encoding is slower for low frequency words and thus colour naming is slower for such words compared to high frequency words. If this delay occurred for all pronounceable letter strings, but not for non-pronounceable letter strings, colour naming would be slower for all pronounceable letter strings leading to negative facilitation.

3.3. What is the effect of a mostly non-lexical trial context?

A long-standing and robust finding in the attentional control literature is that manipulations of the proportion of the different trial types modify Stroop effects (e.g., Kane & Engle, 2003). For example, Stroop interference is smaller when there are a greater proportion (e.g., 75%) of incongruent trials vs. congruent trials (see e.g., Lindsay & Jacoby, 1994; Logan & Zbrodoff, 1979). Accounts for this congruency proportion effect vary (see Braem et al., 2019, for a recent discussion). Within the selective attention domain, prominent theories often posit a proactive control mechanism (e.g., Botvinick et al., 2001; Braver, 2012) where the attention system is biased via a global, top-down manner, triggered by influences such as participants’ expectancies, motivation, and strategies. For example, in an environment where conflicting information (e.g., an incongruent Stroop trial) is often encountered, the conflict monitoring system will signal for more attentional resources to be utilised so as to aid task performance, in contrast to situations where conflict is not encountered as often, and the system does not get triggered. In contrast, Schmidt and Besner (2008) proposed a contingency learning explanation, driven by the fact that the frequencies of the colour-word pairs making up the Stroop stimuli are confounded by response contingencies in the classic PC paradigm. Under this account, a greater proportion of congruent trials leads to more Stroop interference because congruent words become strongly associated with their colour counterparts; that is, the word red predicts the response red. This response contingency is not present when there is a greater proportion of incongruent trials and hence the Stroop effect is smaller. More recently, Spinelli and Lupker (2021; 2022) reported that trial-type proportion manipulations can result in modified Stroop effects even when congruent trials are replaced by non-lexical trials (e.g., repeated-letter trials) trials. They showed that the Stroop effect is smaller, and thus proactive control is stronger, when there is a greater proportion of incongruent trials. Spinelli and Lupker argued that their data provided evidence for the operation of proactive control in a confound-free context. Importantly, for present purposes, their findings suggest that a mostly non-lexical trial context reduces proactive control.

Consistently, according to Kalanthroff et al. (2018)’s model the mostly non-lexical context induces a low task conflict control state, and thus reduces proactive control. When proactive control is low, task conflict is high, and an inhibition mechanism then operates to modify the response threshold to all lexical stimuli. This raising of the response threshold would not happen for repeated letter string trials (e.g., xxxx) because the task unit for word reading would not be activated. Since responses to congruent trials would be slowed relative to non-lexical trials, negative facilitation results. This would predict that the mostly non-lexical context affects all lexical stimuli equally and therefore that response, semantic and phonological conflict would be unaffected (provided a lexical baseline is used in the computation of their magnitudes).

In contrast, arguing from the perspective that positive facilitation results from inadvertent reading2 (Kane & Engle, 2003; MacLeod & MacDonald, 2000), Entel and Tzelgov (2020) reasoned that a larger number of non-lexical trials means that participants are less likely to inadvertently read the congruent word, thereby reducing facilitation and, presumably, reducing interference of all kinds.

Results from a recent study (Kinoshita, Mills, & Norris, 2018) put these interpretations of the effect of a mostly non-lexical context into doubt. They used the proportion of non-word trials manipulation to investigate whether semantic processing in the Stroop task can be controlled. They reasoned that they could manipulate the task of word reading by including a high proportion (i.e., 75%) of non-lexical trials (a rows of #s in this case). According to Entel and Tzelgov’s position, this should reduce semantic processing because a greater proportion of non-lexical trials reduces the likelihood of word reading. According to Kalanthroff et al.’s model, the response threshold for all lexical stimuli is raised by equal amounts suggesting that informational conflict would not be affected. In contrast to such predictions, Kinoshita and colleagues reported larger semantic Stroop effects (i.e., interference induced by colour incongruent items that were not in the set of response colours) despite using neutral words trials as the baseline against which semantic conflict was computed, in the condition with a high proportion of non-lexical trials. The authors argued the effect resulted from reduced control over word processing. This result contrasts with Entel and Tzelgov’s account of the effect of the mostly non-lexical trial context by showing that word processing was more likely in a mostly non-lexical context. It is also inconsistent with Kalanthroff et al.’s model which would predict that informational conflict should not have been affected. Their result is nevertheless consistent with the notion that a mostly non-lexical trial context reduces proactive control (Spinelli & Lupker, 2021; 2022). It is also worth noting that a mostly non-lexical trial context also increased informational conflict (incongruent – congruent) in studies that have included them (e.g., Goldfarb & Henik, 2007).

On the basis of this finding, it could be argued that large, robust negative facilitation effects are more likely to emerge in a mostly non-lexical trial context, not because of the effect it has on a task conflict control mechanism, but instead because it renders informational conflict control less effective leading to increased semantic, phonological and response processing of the irrelevant word. Nevertheless, Kinoshita et al.’s results need to be replicated before any strong conclusions can be drawn. Further studies investigating the effect of a mostly non-lexical trial context on varieties of informational conflict would be informative here.

3.4. Why is there a lack positive facilitation when task conflict control is supposed to be high?

As mentioned above, in their original study, Goldfarb and Henik (2007) reasoned that negative facilitation is not often found under standard Stroop task conditions because there is a sufficiently large enough proportion of lexical stimuli to activate task conflict control. The activation of task conflict control means that the resulting task conflict is minimal and positive facilitation can be therefore expressed in the RT data. If, however, the expectation for a low task conflict is introduced – via a greater proportion of non-lexical neutral trials – and task conflict control is thereby reduced, negative facilitation is observed in RTs. In line with this reasoning, substantial negative facilitation (i.e., ~130ms) was observed under these latter conditions in Experiment 1 of Goldfarb and Henik (2007)’s original study. However, in the control condition of this same experiment, in which the need for task control was cued and expected conflict and control was high, no positive facilitation was revealed, and a non-significant ~21ms of negative facilitation was actually observed. Similarly, in Experiment 2, which Goldfarb and Henik (2007) presented to show that there is no negative facilitation when task conflict control is increased (by swapping non-lexical neutral trials with neutral word trials ensuring the presence of task conflict on every trial), positive facilitation was absent and negative facilitation was present instead, albeit by a non-significant amount (~18ms).

This repeated absence of positive facilitation under conditions in which task conflict control should be high enough to expose it, is somewhat problematic for the task conflict account. The authors have in fact referred to negative facilitation as reverse facilitation, but there is no reversal of facilitation if, in the control condition, positive facilitation is clearly absent. Said differently, the finding of robust negative facilitation observed in Experiment 1 of Goldfarb and Henik’s original study, should be understood in light of null positive facilitation effects when positive facilitation effects are clearly expected (i.e., when no task conflict-related manipulations are applied).

The lack of positive facilitation seems to be a result of the mostly neutral trial context; whether that be non-lexical neutral or non-colour related word neutral trials. If, as suggested in the section above, we interpret the mostly neutral trial context as promoting reduced proactive control, the finding of no positive facilitation in a mostly neutral context would suggest that positive facilitation is itself the result of increased proactive control, which seems counterintuitive given that proactive control should lead to less, not more, word reading. However, given that positive facilitation is beneficial to performance it is conceivable that its expression is related to better control in some circumstances (as argued by the task conflict account).

If reduced proactive control results from a mostly non-lexical context relative to a mostly neutral word context and yet positive facilitation is absent even in a mostly neutral word context, then one might surmise that it is the lack of a mostly colour word context that impedes the expression of positive facilitation. It is clear that more research is needed to understand why positive facilitation is reduced in a mostly neutral trial context (and in other contexts we will go on to discuss such as the Stop-Signal task context). We do not intend to provide an account of this here since it is not directly addressed by the task conflict account of negative facilitation. Nevertheless, along with other trial type proportion effects, this seems to be an effect worthy of further investigation.

3.5. What is the role of proactive control/working memory?

Although related to the above two challenges it is worth highlighting the directly opposing arguments from task conflict theorists. Kalanthroff et al.’s (2018) model predicts that proactive control capacity leads to less negative facilitation. However, there exists robust evidence that working memory capacity is required for the expression of negative facilitation (Entel & Tzelgov, 2020). Entel and Tzelgov have interpreted this as showing that working memory capacity is required for proactive control. Thus, there are two directly opposing accounts of negative facilitation; one that argues that negative facilitation requires proactive control and the other that argues that negative facilitation results from poor proactive control.

4. Is there an alternative to a task conflict account of negative facilitation?

Above we have discussed challenges to the task conflict account of negative facilitation. However, it is important to note that there is currently no alternative account of negative facilitation in the literature. The finding that congruent trials result in longer response times than neutral trials in both selective attention and task switching contexts has been universally interpreted as resulting from competition between task sets. The lack of an alternative, testable account of negative facilitation perhaps attests to the power of the approach. Nevertheless, we set ourselves the challenge of providing an alternative and testable account of negative facilitation in the Stroop and other tasks in the hope that it will permit strong tests of the task conflict account. It is again worth pointing out that our aim is not to invite the reader to send the theoretical constructs of task set control and task conflict to the Occam’s Razor retirement home for superannuated theories, it is rather to encourage attempts to falsify it. Below we present a tentative alternative account that builds on some of the challenges presented above. Each of these sections outlines testable predictions based on this alternative to the task conflict account.

We will argue from the perspective that, in selective attention tasks, the irrelevant task set is not activated, or not activated enough, to influence performance and thus that whole task sets do not compete. We will argue that uncontrolled, obligatory (but not necessarily effortless) SR associations are sufficient to account for negative facilitation in most contexts. That is, a response strongly associated with a particular stimulus (including congruent stimuli) is activated independent of a participant’s goals whether that be the reflexive production of an object’s name on presentation of the object, the motoric response to the picture of an object with a graspable handle, or phonological, semantic or response processing of the irrelevant word in the Stroop task. Whilst we focus mainly on the Stroop task, the general argument can be applied to other tasks – and indeed we do so in later sections.

4.1. An alternative account of negative facilitation in the Stroop task

Our reading of the literature on negative facilitation in the Stroop task leads us to the conclusion that experimental manipulations intended to increase task conflict can also be thought of as manipulations that increase informational conflict. For example, according to the task conflict account, a mostly non-lexical trial context increases task conflict because it creates an experimental context in which task conflict control is not needed (mostly). This manipulation does seem to be important in producing negative facilitation. Indeed, outside of task-switching and stop-signal trial contexts it appears to be the only experimental manipulation that is able to produce a significant effect of negative facilitation (however small) by itself in the RT data, without any other manipulation such as cueing, low working memory load, or exposure to incongruent trials.3 However, a mostly non-lexical trial context has also been shown to increase semantic conflict (Kinoshita, De Wit & Norris, 2017 – see below), a form of informational conflict. In what follows we will outline an alternative of negative facilitation as reported in mostly non-lexical trial contexts, task-switching contexts and stop-signal task contexts – one based on the notion that it is informational conflict that causes negative facilitation, not competition between intentionally and unintentionally activated task sets. We start by considering the baseline against which congruent trials are often compared when negative facilitation is reported.

4.1.1. A Pronounceability Cost

The observance of negative facilitation is determined by whether the baseline condition is non-lexical (e.g., repeated-letter strings) or lexical (colour-neutral words). As we have previously noted, selecting an appropriate baseline, and indeed an appropriate critical trial, to measure the specific component under test is non-trivial (Parris et al., 2022; see also Evans and Servant, 2022). Differences in performance between a critical trial and a control trial might be attributed to a specific variable but this method relies on having a suitable baseline that differs only in the specific component under test (Jonides & Mack, 1984). Nevertheless, task conflict proponents argue that a major difference between repeated-letter strings and colour neutral words is the presence of task conflict on neutral word trials and its absence on rows of Xs. Some researchers (including ourselves) have even used this difference as a measure of task conflict (Augustinova et al., 2019; Ferrand et al., 2020; Kinoshita et al., 2017; 2018). However, it has also been argued that the difference between these two trial types is a form of informational conflict called the lexicality cost resulting from the fact that a word “is known and has meaning” (Brown, 2011, p.86). Repeated-letter and other non-lexical baselines (e.g., a series of nonalphanumeric symbols) differ from lexical stimuli, including conflicting and congruent ones, in terms of this lexicality cost. It is therefore possible that negative facilitation appears, not because non-lexical trials lack task conflict, but because they lack a “lexicality” cost. However, Brown’s (2011) idea of lexicality was not coined to account for task conflict, and sounds somewhat similar to task conflict, albeit eschewing mention of competition between whole task sets. Also, and importantly, one can reasonably ask if there is any explanatory advantage of “lexical” conflict over “task” conflict since both involve the activation of the mental machinery for word reading. However, one big difference is that the latter case requires the selecting, linking, and configuring two sets of processes that accomplish different tasks, and for those collections of processes to compete independently of informational conflict. Moreover, S-R associations are required, at some point, to activate a task set. The former case requires simple S-R associations to proceed unbounded. However, in contrast to Brown’s approach we argue that Brown’s notion of a lexicality cost is best understood in terms of a pronounceability cost; a cost resulting from informational conflict, and is thus not defined as occurring when a word “is known and has meaning” (Brown, 2011: 86), but instead occurs when a letter string is pronounceable (whether it is a word or not).

Brown noted that the term lexicality cost was used because responses to pseudowords (regularly spelled but meaningless words e.g., kluft) are not associated with the same cost (Brown, Roos-Gilbert, & Carr, 1995), indicating that lexical activation is required. However, more recent work has supported Monsell et al.’s finding that pseudowords are in fact associated with the same cost. Kinoshita et al. (2017) compared Stroop performance on five types of colour-neutral letter strings and incongruent words. They included real words (e.g., hat), pronounceable nonwords (or pseudowords; e.g., hix), consonant strings (e.g., hdk), nonalphabetic symbol strings (e.g., &@£), and a row of Xs. They reported that there was a word-likeness or pronounceability gradient.4 with real words and pseudowords showing an equal amount of interference (with interference increasing with string length) and more than that produced by the consonant strings. Consonant strings produced more interference than the symbol strings and the row of Xs which did not differ from each other. The absence of the lexicality effect (defined by colour neutral real words producing more interference than pseudowords) was explained by Kinoshita and colleagues as being a consequence of the sub-lexically generated phonology from the pronounceable irrelevant words interfering with the phonetic encoding (articulation planning) of the target colour dimension. Given these findings, Brown’s lexicality cost is perhaps better thought of as a pronounceability cost. If it is information derived directly from the irrelevant letter string that interferes with colour naming when that letter string is pronounceable, then no recourse to task conflict is needed.

4.1.2. Delaying phonetic encoding of the colour name

Just as lexical conflict was conceived of as a cost irrespective of whether the irrelevant word was incongruent or congruent (Brown, 2011), and just as Kalanthroff et al. (2018) proposed that task conflict inhibits all response representations (thereby raising the response threshold) for all word-like stimuli, this pronounceability cost would be incurred irrespective of congruency. Since undertaking the phonological/phonetic encoding of the irrelevant word occurs automatically in the sense that it is obligatory (with both manual and vocal responses), phonetic encoding of the colour name would be delayed. Moreover, since the phonetic information from the irrelevant word is not the needed response, control would likely be needed to prevent it interfering further (especially with a vocal response Stroop task) and control of automatic processes can be effortful (Diede & Bugg, 2017; Entel & Tzelgov, 2020; Parris, Hasshim & Dienes, 2021). This added level of interference in the colour naming process for congruent relative to non-lexical, non-pronounceable letter strings would also add another point at which noise could interact with performance and thereby increase RT variability (see the section above on the description of Kalanthroff et al.’s (2018) model of task conflict).

Supporting evidence for the delaying of the computation of the colour name due to the phonological/phonetic processing of the irrelevant word can be found in some of the research findings we alluded to above. The finding that low frequency words are colour named more slowly than high-frequency words (e.g., Burt, 2002), indicates that generating sub-lexical phonology and subsequent phonetic encoding of pronounceable letter strings delays the phonetic encoding of the colour name. This would lead to slower colour naming times for all pronounceable letter strings. Furthermore, if, as argued above, the mostly non-lexical (heretofore non-pronounceable string) context employed in task conflict studies also increases processing of the irrelevant word (see above), this would lead to further delay and a bigger pronounceability cost. This delay is akin to that suggested by the response exclusion hypothesis (Mahon et al., 2007) to explain the word frequency and semantic interference effects in the picture-word interference task. Consistent with this theory, our alternative account is based on the notion that somewhere in the processing stream phonetic encoding or the “production-ready” phonetic code of pronounceable irrelevant words delays the encoding or the production of the colour name.

4.1.3. There is no positive facilitation in a mostly neutral stimulus context so a congruent phonetic code does not facilitate performance

One limitation of this account is that when the irrelevant word is presented in a congruent colour, it does not seem to make sense to argue that the sub-lexically generated phonology interferes with the segment-to-frame association processing in articulation planning; such information should facilitate segment-to-frame association processing. However, as discussed above, positive facilitation is no longer happening given the mostly neutral (pronounceable or non-pronounceable) word context and thus there is something about a mostly neutral context that prevents facilitating information from being utilised (see ‘Why is there a lack positive facilitation when task conflict control is supposed to be high?’ above). Further, just as lexical conflict was conceived of as a cost irrespective of whether the irrelevant word was incongruent or congruent (Brown, 2011), and just as Kalanthroff et al. (2018) proposed that task conflict inhibits all response representations (thereby raising the response threshold) for all word-like stimuli, this pronounceability cost would be incurred irrespective of congruency given certain experimental conditions. Since undertaking the phonological/phonetic encoding of the irrelevant word occurs automatically in the sense that it is obligatory (with both manual and vocal responses), phonetic encoding of the colour name would be delayed. Moreover, since the phonetic information from the irrelevant word is not the needed response, control would likely be needed to exclude it and prevent it interfering further (especially with a vocal response Stroop task) and control of automatic processes can be effortful (Diede & Bugg, 2017; Entel & Tzelgov, 2020; Parris, Hasshim & Dienes, 2021).

4.1.4. Phonological processing with manual responses

This account provides a potential explanation as to why the difference between neutral words and repeated letter string trials presented in equal ratios (with no other experimental manipulations and often interpreted as representing task conflict), is harder to observe with manual responses. Kinoshita et al. (2017) reported evidence for sub-lexically generated phonology when participants responded vocally but not when participants responded manually, mirroring the finding that task conflict, when measured as the difference between non-lexical (repeated-letter strings) and neutral word trials, is observed with vocal responses, but not manual responses (Augustinova et al., 2018; Augustinova et al., 2019; Ferrand et al., 2020; Levin & Tzelgov, 2016). Along with Kinoshita et al. (2017), Parris et al. (2019) and Zahedi et al. (2019) have reported data indicating that the difference between manual and vocal responses occurs later in the phonological encoding or articulation planning stage because vocal responses encourage greater phonological encoding than does the manual response (see Van Voorhis & Dark, 1995 for a similar argument). For example, Parris et al. (2019) sought evidence for the use of a serial print-to-speech sub-lexical phonological processing route when using manual and vocal responses by testing for the facilitating effects of phonological overlap between the irrelevant word and the colour name at the initial and final phoneme positions (e.g., row in red vs. bad in red). The results showed phoneme overlap leads to facilitation with both response modes, but a significantly larger effect with vocal responses. This suggests that the significant difference in mean colour-naming latencies between colour-neutral words and repeated letter-strings only with vocal responses (Augustinova et al., 2018; Augustinova et al., 2019; Levin & Tzelgov, 2016) is a result of the extra phonological processing with vocal responses.

Notably, the fact that most reports of negative facilitation come from studies employing manual responses makes the argument that task conflict is harder to observe with manual responses due to reduced phonological/phonetic processing seem rather self-defeating. Importantly however, it is being argued that observing a difference between neutral word and non-pronounceable letter strings with a manual response is more difficult in a context where the trial types are presented in equal proportions given that phonological processing is reduced with a manual response. When there is a mostly non-pronounceable trial context, control over word processing is potentially much reduced (Kinoshita et al., 2018) and so the differences between trial types that are pronounceable and those that are not is magnified.

4.2. Accounting for negative facilitation that is observed without a mostly non-lexical trial context

4.2.1. Negative facilitation in a task-switching context

If negative facilitation reflects task conflict, it would be expected to increase in the task switching context. More specifically, if task set competition were responsible for negative facilitation, it would also be expected that negative facilitation would be larger on task switching trials compared to trials on which participants repeat the same task, since this would be when task conflict is maximised. Rogers and Monsell (1995) reported evidence in support of this.