Abstract

Selenium enriched yeast is the most prevalent source of organic selenium for humans and animals. In this study, an effective capillary zone electrophoresis method was established to quantify total selenium in yeast biomass by measuring selenite level in post incubated culture media. The detection of selenite could be achieved within 7.9 min under the condition of a mixture buffer of 85 mM Na2HPO4 and 0.5 mM CTAB (pH 9.37), –5 kV separation voltage with 1.0 psi × 30 s injection at 200 nm. The range of calibration curve linearity of the standard was from 5 to 300 mg/L (r2 = 0.99998), and the recovery was 102.4%. Owing to the ease of sample collection and simple detection, this method is convenient for the evaluation of total selenium accumulated in yeast cell biomass and helps to guide the production of selenium enriched yeast.

Keywords: capillary zone electrophoresis, selenite enriched media, total selenium, selenium enriched yeast

Selenium is a metalloid element discovered in 1817 by a Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius [1]. It is an element of VIA group in the periodic table and is referred to as chalcogens. It occurs in different valence states in the environment [2]. The introduction of selenium as one of the important elements for life in 1957 was due to the analytical methods development and studies conducted by Schwarz and Foltz [3]. Since then, selenium has been reported to be a fundamental element for human and animal life [3–5].

According to the World Health Organization, selenium insufficiency is one of the most prevalent dietary deficiencies in the world [6] and is attributed to a variety of diseases, including heart disease, cancer (for instance, people with low plasma selenium concentrations have a 4 to 5 fold greater risk of prostate cancer) [7], infertility [8], liver necrosis [9], immune system malfunction [10], increased vulnerability to infections (including COVID-19 and HIV) [11], and increased risk of mortality [12].

Selenium-enriched yeast (mostly the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae), the most commercialized type of selenium supplementation, is accomplished by a cultivating yeast in a selenite enriched medium. Selenite is transformed into organic selenium compounds, hence yeast provides an easily available and low-cost organic source of the required daily intake of selenium [13–15] and is indicated as a treatment or added to the human diet and beverages to compensate for selenium deficiency [16]. To monitor the efficiency of selenium enriched yeast production, Se content should be measured.

Numerous analytical methods have been reported for measuring selenium content in yeast cell biomass. In some methods, total Se was determined in digested yeast without the need for selenium speciation. The incomplete yeast digestion leads to obtaining a low Se concentration, as reported in hydride generation coupled to atomic absorption spectrometry (HG-AAS) or atomic fluorescence spectrometry (HG-AFS) [17, 18] and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), the principle selenium determination technique [19]. Otherwise, analytical methods such as capillary electrophoresis (CE) [20] and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [21] were used to determine total Se via selenium speciation. CE is a green alternative to HPLC and other analytical techniques due to its low vapor pressure, tiny sample volume, and quick analysis time [22, 23].

The speciation of selenium results in a gap between the sum of identified selenium species in the extracted sample and total selenium concentration, consequently minimizes the accuracy of the analytical procedure [17]. Additionally, there is a need to hyphenate CE to a highly sensitive detector such as ICP-MS to detect low concentrations of selenium species [23].

Thus, whatever the technique utilized, there was a need for selenium extraction process which is difficult due to its various oxidation states and potential volatilization [24], the extraction process is time-consuming and includes hazardous chemicals such as hydrochloric acid [21], nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide [25] and expensive enzymes [21].

Otherwise, without the need for selenium extraction, a spectrophotometric method for selenite detection in culture media for total selenium evaluation in yeast cells has been reported [26]. Nevertheless, chemical reagents were utilized to yield a change in culture medium color that was related to selenite concentration, and the correlation was poor.

The aim of the present work was to overcome all these challenges and establish a straightforward, quick, and accurate method for measuring total selenium without the need to extract selenium from yeast cells.

Total selenium content in S. cerevisiae BY4741 cells was determined directly using a novel capillary zone electrophoresis method by evaluating the changed level of selenite in post-incubated culture medium.

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents and materials. Sodium selenite (99% purity) was purchased from Sigma Co. (Shanghai, China). Disodium hydrogen orthophosphate was purchased from Shanghai Taitan Scientific, and cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co. Polyether sulfone membrane filters (0.22 μm) were purchased from ANPEL Laboratory Technologies Inc. (Shanghai). All other chemicals of analytical grade were obtained commercially.

Sample preparation. For this study, Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4741 strain was obtained from Invitrogen (Camarillo, CA, USA). The strain was stored at 4°C in a refrigerator on yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) agar and regularly subcultured. Yeast cells (OD600 of 0.1) were inoculated into 2 mL of synthetic complete SC medium in the absence or presence of 100 mg/L sterile sodium selenite and then incubated in a rotary shaker at 30°C, 180 rpm for 36 h. Samples were obtained by centrifugation of post-incubated yeast suspension at 8000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was used as CE sample, and the sediment was dried at 60°C until a constant weight. The obtained yeast biomass dry weight (DW) was given per 1 L of medium (g/L).

Capillary electrophoresis separation method. The CE separation process was carried out on a Beckman PA800 Plus CE system (Beckman Coulter Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA) equipped with a photodiode array (PDA) detection system and a fused silica capillary with an internal diameter of 50 μm, an effective length of 38 cm, and a total length of 48 cm. 32 Krarat Station Software was used to control the instrument. The buffer was a mixture of Na2HPO4 and CTAB [27]. The buffer was prepared daily, and the pH of the buffer solution was adjusted using ammonium or orthophosphoric acid [28], then filtered and degassed in an ultrasonic bath before use. For capillary rinsing, 1 and 0.1 M NaOH solutions, 0.1 M HCl as well as purified water obtained through a Milli-Q equipment were utilized. Before each run, the capillary was preconditioned by successively flushing with 1 M NaOH, 0.1 M NaOH, and water for 2 min and buffer for 5 min. By using a polyether sulfone filter (0.22 μm), all solutions were filtered.

The parameters utilized in the optimization of the CE separation conditions were: (a) detection wavelength, (b) concentration of Na2HPO4 and CTAB buffer between 65–95 mM and 0–1 mM, respectively, (c) buffer pH (range of 7.38–10.37), (d) separation voltage, (e) injected volume. The separation temperature was set at 35°C [28]. All solutions were filtered using a polyether sulfone filter (0.22 μm).

For the method validation, selenite standard solution (1000 mg/L) was diluted to various accurate concentrations with the supernatant of post-incubated culture media. These standard solutions were used fresh. The standard solutions of various accurate concentrations were filtered with a polyether sulfone filter (0.22 μm). The method linearity was determined by using a calibration curve obtained under the optimized conditions. Because the interference of other substances in the culture medium caused changes of the peak width, the peak height of selenite did not increase in proportion with the increase in selenite concentration. Based on the good baseline, the curve was constructed by plotting the average of peak areas rather than peak heights or reduced areas vs. the concentration of the standards. The calculation of limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) was achieved by using the calibration curve made in triplicate as 3.3 σ/S and 10 σ/S, respectively, where S is the slope of the calibration curve, σ is the standard deviation of the intercept [22].

The method precision was determined by between- and within-day variations. The within-day variability was determined by repeated analysis of a single volume of standard compound for six times. Between-day variability was evaluated by the average of triplicate analysis on six different days. The optimized separation conditions were utilized to investigate a variety of samples, including the supernatant of S. cerevisiae BY4741 strain cultured in media in the absence and presence of 100 mg/L selenite as well as culture media only (without yeast inoculation) without and with 100 mg/L selenite. The recovery was accomplished by adding a known quantity of selenite standard to the sample with its known concentration within the linear range. The quantity of the analyte was obtained using the corresponding calibration curve. The obtained value was calculated per culture volume. Considering the biomass yield, the content of selenium accumulated in 1 g of dry yeast cells was calculated.

Statistical analysis. Each result was obtained as the mean value of at least three replicate measurements, and experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Optimization of capillary zone electrophoresis conditions. Effect of detection wavelength. Initially, at the wavelength ranging from 190 to 300 nm, selenite standard was scanned via PDA detector. Figures 1a, 1b exhibit the three-dimensional and contour graphs of the absorbance spectra. The highest peak of selenite was observed at the wavelengths of 200 and 210 nm. Previously, 210 nm was commonly used as the detection wavelength for selenite by CE [28]. Under such two different wavelengths, selenite standard solution was examined, and the area at 200 nm was found to be more than 1.6 times higher than that at 210 nm (Figs. 1c, 1d). Therefore, the detection wavelength of 200 nm was more appropriate for selenite detection.

Fig. 1.

Effects of detection wavelength on selenite detection. (a) A three-dimensional graph of selenite ranging from 190 to 300 nm; (b) a contour graph of selenite at 200 nm; (c) CE detection of selenite standard at 200 nm; (d) CE detection of selenite standard at 210 nm.

Effect of concentrations of buffer solution components. To avoid the interference of other compounds of the media, selenite standard (50 mg/L) was added to the supernatant collected from the culture medium SC cultivated with S. cerevisiae BY4741 strain for 36 h in the following experiments.

Na2HPO4 concentration. Phosphate and borate buffers are the most commonly used with direct UV detection [28, 29]. Herein, phosphate buffer was utilized. The effects of a range of sodium phosphate concentrations (65–95 mM; pH 8.37) were investigated.

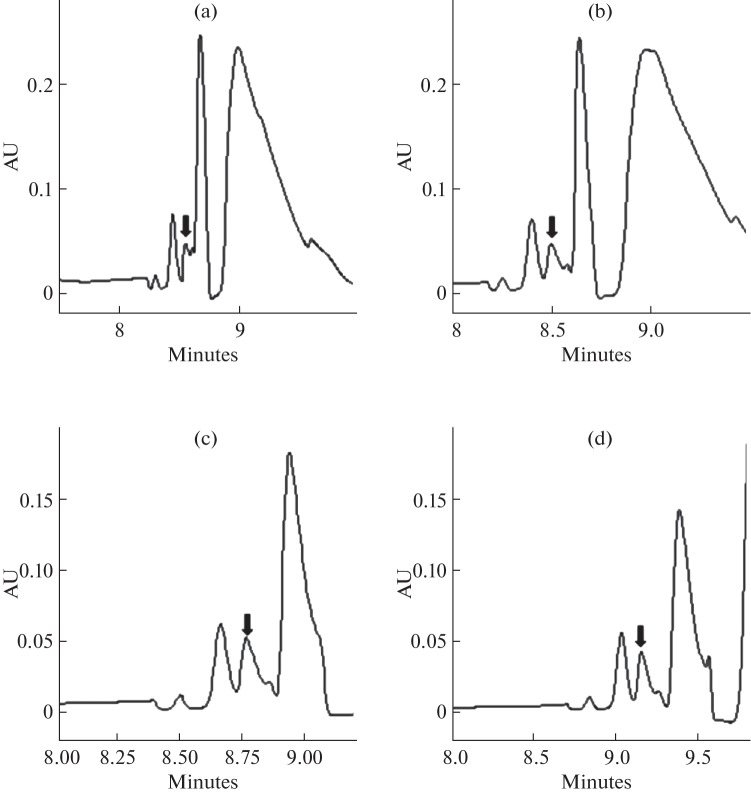

As shown in Fig. 2, selenite separation was partial at 75 mM, whereas no separation was observed at 65 mM. At 85 and 95 mM, the separation was more effective. At higher concentrations, no more effective separation was accomplished. They almost displayed the same result at 95 mM (data not shown). The various concentrations investigated in this study revealed that the buffer concentration has a minor effect on migration time and a significant effect on separation efficiency. 85 mM phosphate buffer was chosen as the optimal concentration to obtain greater separation, faster detection, and higher peak.

Fig. 2.

Effects of Na2HPO4 concentration on selenite detection: (a) 65; (b) 75; (c) 85; (d) 95 mM. The arrow points to selenite in each figure.

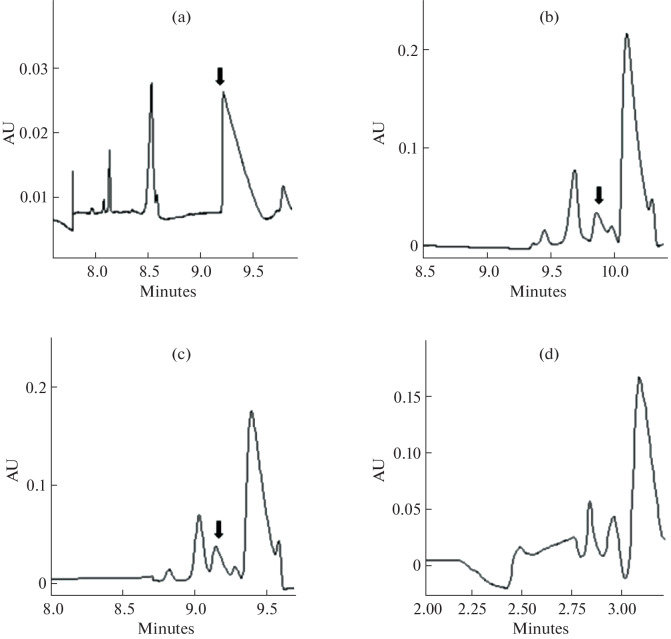

Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide concentration. When the buffer was prepared only with Na2HPO4, the slow migration of selenite ions resulted in a wide and asymmetric peak with a migration time of 45 min, as shown in Fig. 3a; similar result was reported [27, 30]. Hence, it was crucial to add alkyl ammonium salt (CTAB) as an electroosmotic modifier to the buffer to shorten the migration time and obtain a symmetric peak. CTAB concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mM (pH 8.37) were investigated. Figs. 3b–3d show the significant effect of CTAB on the migration time. Obviously, the higher the concentration, the shorter the migration time, consequently resulting in a symmetric peak and rapid detection. Regarding separation efficiency, selenium separated partially at 0.1 mM, whereas there was complete separation at 0.5 mM as shown in Figs. 3b, 3c, respectively. At a higher concentration of 1 mM, there was no separation of selenium as shown in Fig. 3d. Based on these findings, 0.5 mM concentration was chosen as the optimal concentration.

Fig. 3.

Effects of CTAB concentration on selenite detection: (a) 0; (b) 0.1; (c) 0.5; (d) 1 mM. The arrow points to selenite in each figure.

Buffer pH. The buffer pH played a substantial role in CE separation. There was no detection of selenium at pH less than 8.37 which was used as the appropriate pH for inorganic selenium detection [28]. The same results were achieved in this investigation (Figs. 4a, 4b) with no detection of selenite at pH 7.37 and a successful separation of selenite at pH 8.37. Selenite peak conveyed to the left at higher pH 9.37, resulting in complete separation. At pH 10.37, more movement of selenite peak to the left resulted in interference with another peak. When pH was raised, the migration time was slightly slowed. Hence, pH 9.37 was determined as the optimal pH for further study based on separation efficiency.

Fig. 4.

Effects of buffer pH on selenite determination. pH: (a) 7.37; (b) 8.37; (c) 9.37; (d) 10.37. The arrow points to selenite in each figure.

Effect of separation voltage. To investigate the effect of voltage on the separation of selenite, different applied voltages of –2.5, –5.0, and –7.5 kV using 85 mM Na2HPO4 and 0.5 mM CTAB buffer (pH 9.37) with 1.0 psi × 30 s injected volume at 200 nm were used. Figures 5a−5c reveal the results of the electropherograms of a sample containing 50 mg/L selenite. When a high voltage was applied, the migration time was obviously reduced. At –7.5 kV, the migration time was greatly reduced, resulting in poor separation resolution. –5 kV had an advantage over –7.5 kV due to factors including separation efficiency and peak height. Therefore, –5 kV was selected as the optimal voltage.

Fig. 5.

Effects of separation voltage and injected pressure on selenite determination: (a) -2.5 kV; (b) -5 kV; (c) -7.5 kV; (d) 1.0 psi; (e) 1.5 psi; (f) 2.0 psi. The arrow points to selenite in each figure.

Effect of injected sample volume. Injection pressure could be used to control the volume of samples injected. The impact of this parameter on the result of the quantification of selenite in the sample was explored. As shown in Figs. 5d–5f, with the increase in the injected pressure, the separation became less effective. Among all the injected pressures examined, i.e., 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 psi, 1.0 psi provided the best separation. When the pressure was less than 1.0 psi, the peak was smaller (data not shown). Hence, 1.0 psi was chosen as the optimal injected pressure.

The optimized resolution was attained with an electrolyte containing 85 mM sodium phosphate buffer and 0.5 mM CTAB (pH 9.37), –5 kV applied voltage, and 1.0 psi × 30 s injected volume at 200 nm detection wavelength. The final optimum CE separation conditions expressed a repeatable separation with the average retention time of 7.9 min, as shown below (analyte—selenite):

| Linearity range, mg/L | r2 | Retention time, mean value, min | CV, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5–300 | 0.99998 | 7.9 | 0.8 |

Method validation. Linearity and precision. The linearity was examined by construction of a calibration curve in triplicate which represented the equation y = 3808.6x – 7794.7 (r2 > 0.9999). The method is linear in the range of 5–300 mg/L.

Within- and between-day precision values were 99.1 and 98.1, obtained from the average of 6 and 18 experiments, respectively. As shown in Table 2, the coefficients of variation (CVs) were relatively low for within-day (0.4%) and between-day (1.7%) precision, as shown below (analyte—selenite):

| Within-day, mean, mg/L (n = 6) | CV, % | Between-day, mean, mg/L (n = 18) | CV, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 99.1 | 0.4 | 98.1 | 1.7 |

Detection limit, quantification limit and recovery. The LOD and LOQ were 3 and 9 mg/L, respectively. The recovery test confirmed accuracy of the method, since the average value was 102.4% with a CV of 1.6%, as shown below (analyte—selenite):

| LOD, mg/L (n = 3) | LOQ, mg/L (n = 3) | Recovery, % | CV, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 9 | 102.4 | 1.6 |

Quantification of total selenium in yeast cell biomass. Total selenium concentration in yeast cell biomass was evaluated according to the change in selenite content after yeast was cultured in selenite enriched medium for a certain time.

The developed CE method was applied for the evaluation of selenite content in different samples, as shown in Figs. 6a–6d. The samples exploited in this experiment were the negative control prepared from the supernatants of S. cerevisiae BY4741 cells incubated in medium without selenite and the experimental sample prepared from the supernatant of the same strain cultivated in 100 mg/L selenite enriched medium. The positive control was the medium containing 100 mg/L selenite with no yeast inoculation. Only culture medium was the negative control for the positive control.

Fig. 6.

The optimized CE separation of selenite in the supernatant of different samples. (a) S. cerevisae BY4741 strain cultivated in SC media; (b) S. cerevisae BY4741 strain cultivated in SC medium + 100 mg/L Na2SeO3; (c) SC medium; (d) SC medium + 100 mg/L Na2SeO3. The arrow points to selenite in each figure.

Theoretically, it was assumed that the difference between the initial concentration of 100 mg/L and the concentration of the tested sample was related to selenite associated with yeast cells biomass. Due to a variety of factors that could cause selenite content loss [31–36], any change in selenium content in the culture media was excluded that was not due to selenite accumulation in yeast biomass. Therefore, the positive control sample was incubated under the same conditions as the experimental sample and considered as the initial concentration. After the incubation period, as shown below, selenite concentrations in the experimental and control samples were 49.4 and 69.0 mg/L, respectively, according to the standard equation.

| Sample, mg/L | CV, % | Control, mg/L | CV, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 49.4 | 0.5 | 69.0 | 2.8 |

Consequently, 19.6 mg/L was the quantity accumulated in yeast biomass. The obtained value was calculated per culture volume. Then, the content of total selenium accumulated in 1 g of dry yeast was calculated which was 43.6 mg/g DW.

CONCLUSIONS

In this work, a novel, simple, accurate, and repeatable capillary zone electrophoresis method for the quantification of selenite in the culture media was developed. This study was successful in measuring remnant selenite in post-incubated selenite enriched media, consequently evaluating the concentration of selenium accumulated in yeast cells biomass. This method can be useful for monitoring the effective strains and conditions for better selenium enriched yeast production.

FUNDING

This work was sponsored by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2232021G-04).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kieliszek M. Molecules. 2019;24:1298. doi: 10.3390/molecules24071298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong J., Wang H., Yao J., He Q., Ma J., Yang J., Liu C., Chen Y., Huangfu X., Liu H. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022;422:126852. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kieliszek M., Błażejak S. Molecules. 2016;21:609. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X., Wang X., Liu G., Xu Y., Wu X., Yi R., Jin F., Sa C., Su X. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021;48:153. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2021.4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duntas L.H., Benvenga S. Endocrine. 2015;48:756. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0477-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J., Wang B., Zhang D., Wu Y. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1993. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsueh, Y.M., Su, C.T., Shiue, H.S., Chen, W.J., Pu, Y.S., Lin, Y.C., Tsai, C., and Huang, C.Y., Food Chem. Toxicol., 2017, vol. 107, part A, p. 167. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Li M., Zhang Y., Li S. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2020;19:753. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2020.1786739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li T., Zhang J., Wang P.J., Zhang Z.W., Huang J.Q. Front. Physiol. 2021;12:696256. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.696256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schomburg L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:8532. doi: 10.3390/ijms22168532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge J., Guo K., Zhang C., Talukder M., Lv M.W., Li J.Y., Li J.L. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;773:145442. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z., Chang C., Zhang Y., Chai Z., Li J., Qiu C. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:14533. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93873-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kieliszek M., Błażejak S. Nutrition. 2013;29:713. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pérez-Corona M.T., Sánchez-Martínez M., Valderrama M. J., Rodríguez M.E., Cámara C., Madrid Y. Food Chem. 2011;124:1050. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.07.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assunção M., Martins L. L., Mourato M. P., Baleiras-Couto M. M. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;31:1899. doi: 10.1007/s11274-015-1930-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mapelli V., Hillestrøm P.R., Patil K., Larsen E.H., Olsson L. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;12:20. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2011.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bierla K., Szpunar J., Yiannikouris A., Lobinski R. TrAC . Trends Anal. Chem. 2012;41:122. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2012.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mena M., Gomez M., Palacios M., Camara C. Lab. Autom. Inf. Manage. 1999;34:159. doi: 10.1016/S1381-141X(99)00018-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thosaikham W. SNRU . J. Sci. Technol. 2018;10:178. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendahl L., Gammelgaard B. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2004;19:143. doi: 10.1039/b307474a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bird S.M., Uden P.C., Tyson J.F., Block E., Denoyer E. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 1997;12:785. doi: 10.1039/A701429E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedroso T.M., Schepdael A.V., Salgado H.R.N. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2019;2019:1456313. doi: 10.1155/2019/1456313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morales R., López-Sánchez J.F., Rubio R. TrAC . Trends Anal. Chem. 2008;27:183. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2007.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleckner A.E., Kakouros E., Robin Stewart A. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 2017;15:363. doi: 10.1002/lom3.10164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazard M., Blanquet S., Fisicaro P., Labarraque G., Plateau P. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:32029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kieliszek M., Błażejak S., Płaczek M. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2016;35:90. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert M., Demesmay C., Rocca J.L. Fresenius’ J. Anal. Chem. 1995;351:426. doi: 10.1007/BF00322913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng J., Greschonig H., Liu F., Kosmus W. Trace Elem. Electrolytes. 2000;17:40. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker E.B., Walker J. C., Zaugg S. E., Davidson R. J. Chromatogr. A. 1996;745:111. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(96)00378-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrold M.P., Wojtusik M. J., Riviello J., Henson P. J. Chromatogr. A. 1993;640:463. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(93)80216-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Measures C.I., Burton J.D. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1980;120:177. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(01)84361-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pyrzyńska K. Talanta. 2001;55:657. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(01)00511-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pyrzynska K. Anal. Sci. 1998;14:479. doi: 10.2116/analsci.14.479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cobo M.G., Palacios M. A., Cámara C., Reis F., Quevauviller P. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1994;286:371. doi: 10.1016/0003-2670(94)85083-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caacute G. Cobo, M., Muñoz, R., Quevauviller, P., and A. Palacios, M. Analyst. 1998;123:947. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Héninger I., Potin-Gautier M., de Gregori I., Pinochet H. Fresenius’ J. Anal. Chem. 1997;357:600. doi: 10.1007/s002160050221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]