Sir,

Geographic tongue (GT) is commonly associated with psoriasis and has been proposed to serve as a potential marker of disease severity at initial diagnosis.[1,2] Nevertheless, its morphological evolution during treatment has not yet been documented. Herein, we present a patient with generalised pustular psoriasis (GPP) and report the variation of GT throughout the treatment period.

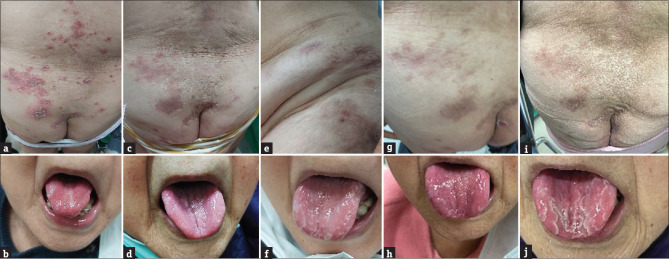

A 90-year-old female, with no history of plaque psoriasis or nail changes, presented widely distributed yellowish pustules and scaling on an erythematous–oedematous base involving primarily her trunk and four extremities for three months [Figure 1a]. Using the Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (GPPASI),[3] the patient received a total score of 36.8 out of 72. She reported that lesions would partially resolve for a few days, but recurred periodically. She also complained of malaise, intermittent fever, and arthralgia that accompanied a burning sensation of the affected skin areas during flare-ups. On examination, there were erythematous patches in the dorsum of the tongue with serpiginous, white borders [Figure 1b], but the patient was not aware of the asymptomatic oral lesions. GPP with GT was diagnosed based on clinical examinations, and a skin biopsy was refused by the patient.

Figure 1.

Clinical photographs of generalised pustular psoriasis and geographic tongue at the first clinical visit and at follow-ups. The initial presentations were (a) widely distributed yellowish pustules and scaling on erythematous–oedematous base involving primarily her trunk and four extremities, and (b) erythematous and atrophic patches in the dorsum of the tongue with serpiginous white borders. (c and d) Appearance at 2nd week of follow-up visit with further, concurrent improvement of skin and tongue lesions. (e and f) Appearance at 4th week of follow-up visit showed sustained improvement of skin, but recurrence of geographic tongue with few pustular eruptions. (g and h) Appearance at 6th week of follow-up visit showed sustained improvement of skin and partial fading of geographic tongue. (i and j) Appearance at 8th week of follow-up visit showed sustained improvement of skin but a repeat recurrence of geographic tongue

After discussion, 210 mg of brodalumab was administered weekly for the first two doses, followed by biweekly intervals from the third dose. Topical calcipotriol/betamethasone ointment was also prescribed. At her first one-week follow-up visit, the patient showed significant improvement with dried-up pustules, much less silvery scales, and ameliorations of other systemic manifestations including malaise and arthralgia. Her skin constantly improved upon the two-, four-, six, and eight-week follow-up visits with gradually declining GPPASI scores [Figure 1c, e, g, i]. However, the condition of GT showed a fluctuating pattern during the treatment period. It resolved in the first and second week, recurred in the fourth week, partially faded in the sixth week, and then became obvious again in the eighth week [Figure 1d, f, h, j]. Few pustular eruptions were observed along with the exacerbation of GT, despite the general GPPASI scores having revealed improvements. The patient received six doses of brodalumab in total, and, on the last follow-up in week 13, showed no recurrence of skin or tongue lesions.

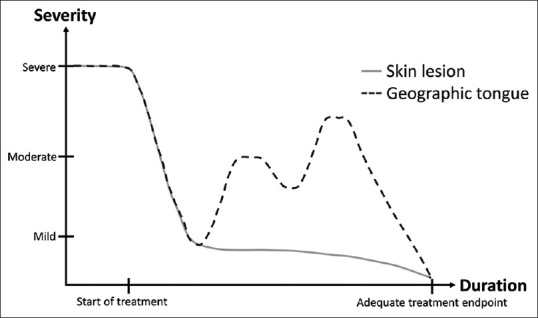

Till date, GPP is still an intractable disease that is potentially life-threatening if left untreated. Numerous treatment strategies for GPP have been developed, but there is no consensus on a stepladder treatment algorithm due to the lack of a good indicator that guides when to stop, continue, or restart a therapy. In our case, the fluctuating pattern of GT, contrasting with the stepwise improvement of the skin, implied that the patient had not achieved complete remission. Previous studies have demonstrated shared histopathological features, common human leukocyte antigen marker, and similar inflammatory pathway between GT and psoriasis,[4] strengthening the association within. With the prosperous development of novel biologic agents for psoriasis in recent decades,[5] administration of biologics often achieves rapid control of pustules, erythema, and pruritus. However, the true disease activity may be obscured by these rapidly improved markers. In our case, we suggest that the oscillating curve of GT is closer to the actual disease situation compared to the rapid suppression of skin lesions [Figure 2]. Close follow-up of oral manifestations in addition to the observation of skin changes in psoriasis may help with the determination of adequate treatment length and precise treatment goals.

Figure 2.

A diagram showing the relationship between severity (y-axis) of skin and tongue and duration (x-axis) in generalised pustular psoriasis during treatment. The solid line represents the change of skin condition, and the dashed line represents the change of geographic tongue. Measurement scale of skin utilised the Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (GPPASI), with a score of <10 indicating mild disease, a score of 5–10 indicating moderate disease, and a score of >15 indicating severe disease. Measurement scale of geographic tongue utilised a geographic tongue severity index developed by Picciani et al., with a score of <7 considered as mild, a score of 7–12 considered moderate, and a score of >12 considered severe. The unit of treatment duration is weeks

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Picciani BLS, Silva-Junior GO, Michalski-Santos B, Avelleira JCR, Azulay DR, Pires FR, et al. Prevalence of oral manifestations in 203 patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1481–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavinas Sayed BP, Teixeira-Souza T, Almenara ÁC, Azulay-Abulafia L, Hertz A, Mósca-Cerqueira AM, et al. Oral investigation in childhood psoriasis: Correlation with geographic tongue and disease severity. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2020;5:23–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, Burden AD, Tsai TF, Morita A, et al. Inhibition of the interleukin-36 pathway for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:981–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1811317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogueta CI, Ramírez PM, Jiménez OC, Cifuentes MM. Geographic tongue: What a dermatologist should know. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed) 2019;110:341–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krueger J, Puig L, Thaçi D. Treatment options and goals for patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(Suppl 1):51–64. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]