Abstract

Pollen food allergy syndrome (PFAS) is a food allergy that manifests as hypersensitivity symptoms of the oropharyngeal mucosa on ingesting specific foods, and findings resemble herpetic gingivostomatitis. Few reports of PFAS caused by consuming radishes are found in the literature. A 31-year-old man presented to our department with stomatitis and pharyngeal pain. He had no history of allergies. Herpetic gingivostomatitis was suspected. He was admitted to the emergency room a few days later complaining of oral and epigastric pain. Symptoms were similar to those reported previously. He reported frequently consuming raw Japanese radish (Raphans sativus L.) which gave rise to his symptoms. Japanese radish was suspected as the allergen. The skin-prick test confirmed the diagnosis of PFAS. PFAS can be diagnosed easily once the food-causing symptoms are identified. Upon encountering widespread erosion in the oral cavity, it is essential to consider PFAS as the possible cause.

Keywords: Herpetic gingivostomatitis, Japanese radish, pollen food allergy syndrome, Raphans sativus L., skin prick test

Introduction

Pollen food allergy syndrome (PFAS) is a type of food allergy that manifests as hypersensitivity symptoms of the oropharyngeal mucosa after ingesting specific foods such as fruits and vegetables.[1] The symptoms appear similar to those of herpetic gingivostomatitis,[2] and guiding diagnosis can be challenging unless the patient is aware of food allergies. Furthermore, these symptoms can also appear in parts other than the oral cavity. Few reports of PFAS caused by consuming radishes are found in the literature. We present a case of PFAS caused by raw Japanese radish (Raphans sativus L.).

Case history

A 31-year-old man presented to our department with stomatitis and pharyngeal pain. He reported having a fever of 38°C, general malaise, epigastric pain and pain in the oral cavity a few days prior. His history included reflux esophagitis and haemorrhoids. He had no history of allergies or atopy. Prior to his visit, the general malaise and epigastric pain had improved. Minor aphthae were observed in the soft palate and mandibular gingiva; the hard palate had slightly eroded [Figure 1]. Herpetic gingivostomatitis was suspected based on findings of the oral mucosa. Blood test results showed a slightly increased C-reactive protein level of 2.96 mg/dL, total leukocyte count of 8390 cells/μL, positive herpes simplex virus Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody titre (44.2 times the normal value) and Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody titre less than 0.80, which was negative. His stomatitis showed improvement. He was instructed to gargle with azulene sodium sulfonate. A week later, the stomatitis and pharyngeal pain improved almost completely. However, 3 weeks after the initial visit, he was admitted to the emergency room with severe epigastric and oral pain. His symptoms were similar to those at the first visit. Upon detailed history taking, he mentioned eating raw-grated Japanese radish frequently. Thus, we suspected an allergy to Japanese radish, and an antihistamine was administered. Interestingly, allergic symptoms did not appear when eating cooked Japanese radish.

Figure 1.

Oral findings at the first visit. Minor aphtha was found on the soft palate and mandibular gingiva, and erosion was found on the hard palate (arrow)

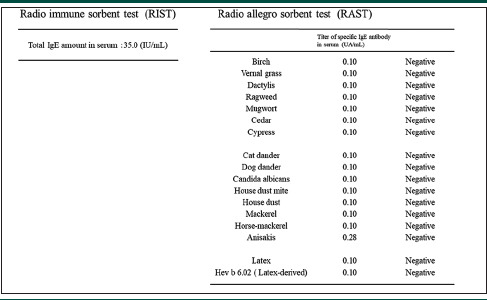

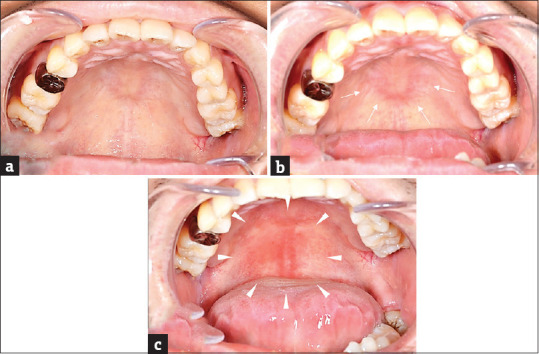

We suspected his condition as PFAS and Japanese radish as the allergen. A skin-prick test and oral challenge test were performed at the dermatology department. The radio-immuno-sorbent test (RIST) and radio-allergo-sorbent test showed negative results [Table 1]. Skin-prick test using grated raw radish and non-grated raw radish found the former as an allergen, while the latter tested negative. A sample was dropped onto the skin, pricked with a prick needle and assessed after 15 min. Histamine was used as a control. A 6 × 6-mm wheel was observed for histamine, while a 3 × 3-mm wheel was observed for grated radish. From this, grated radish was determined to be prick test positive. Considering the risk of anaphylactic shock, radish was not used for the oral challenge. Instead, mustard and wasabi, which belong to the same Brassica family, were used. An oral challenge test was performed using mustard and wasabi; the patient experienced a tingling sensation in the palate immediately after ingestion, and the mucous membrane appeared red [Figure 2].

Table 1.

Results of the radio immune sorbent test (RIST) and radio allegro sorbent test (RAST)

|

Figure 2.

Oral findings at the time of the oral challenge test (a) No obvious redness observed on the palatal mucosa before the oral challenge test (b) After ingestion of mustard, mild redness observed on the mucosa of the hard palate (arrow) (c) After ingestion of wasabi, a wide range of mucosal redness observed from the hard palate to the soft palate (arrowhead)

After eating raw Japanese radish, pain appeared in the oral cavity and pharynx, and the skin-prick test result was positive; consequently, we diagnosed his condition as PFAS caused by Japanese radish. We recommended that the patient limits the intake of foods belonging to the Brassica family, including radish. An antihistaminic drug and injectable epinephrine were prescribed as a precaution.

Discussion

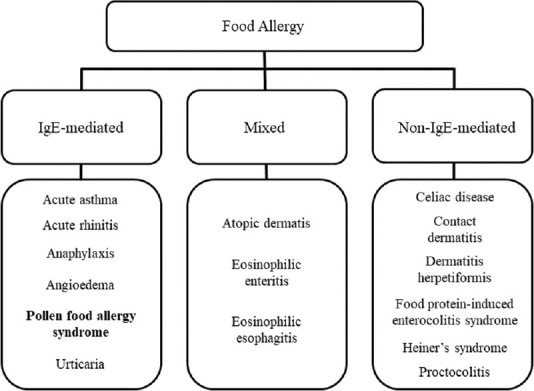

Food allergens that cause conventional intestinal sensitization are termed class I food allergens, and proteins in fruits and vegetables causing allergies owing to cross-reactivity with the pollen antigen are termed class II food allergens.[3] Class I food allergens are resistant to heat and digestive enzymes; thus, the symptoms appear systemically. Class II antigens are not resistant to heat and digestive enzymes; thus, their symptoms are often localized to the oropharynx. PFAS is included in class II food allergies. PFAS is usually restricted to oral and perioral regions, but be aware that it may cause systemic symptoms.[4] Most sensitizers causing PFAS include pollen and latex, with many of these agents being key components of food. PFAS is a new concept in food allergy and is classified as a special type of immediate allergy.[5] Food allergies are classified into three types: IgE-mediated, mixed, and non-IgE-mediated [Figure 3].[6] This case is an IgE-mediated type of food allergy caused by the induction of IgE by Radish as an allergen. PFAS is included in IgE-mediated type of food allergy.

Figure 3.

Classification of food allergies based on IgE

The diagnostic criteria for PFAS proposed by Muluk and Cingi[7] include a history and positive skin-prick test result triggered by fresh food extract. Oral challenge results are normally positive with raw food and negative with the cooked version. In our case, oral lesions and positive skin-prick test results were present and conformed to the aforementioned diagnostic criteria; thus, a definitive diagnosis of PFAS caused by Japanese radish was made.

Herein, the allergic symptoms appeared in both the oropharynx and abdomen. However, consuming cooked radish did not induce any symptoms. Therefore, this was classified as a class II food allergy case. Mustard, which belongs to the same Brassica family as radish, reportedly cross-reacts with mugwort.[8] However, RIST investigations were negative, including those for mugwort, and the sensitized allergen could not be detected.

Ausukua et al.[2] mentioned “viral infections (herpetic)” as a differential diagnosis for PFAS. In our case, we initially suspected herpetic gingivostomatitis because of fever, general malaise and findings of the oral mucosa. Vegetables of the Brassica family, such as radish, mustard and wasabi, contain a volatile substance called isothiocyanate, a component giving them their spicy taste. Glucosinolate is a precursor of isothiocyanate. While glucosinolate itself is not volatile, it chemically reacts with an enzyme called myrosinase that is released after the plant cells are destroyed, yielding isothiocyanate.[9] While the result of the prick test using grated raw radish was positive for our patient, the result of the prick test using non-grated radish was negative. Grating raw radish destroys cells, causing glucosinolate and myrosinase to chemically react with each other over a sufficient period to form isothiocyanate. It was speculated that the non-grated raw radish did not contain enough isothiocyanate to induce allergy. Thus, isothiocyanate was considered an allergen in our case.

PFAS can be prevented by avoiding the ingestion of foods containing culprit allergens. In addition, consuming antihistaminic drugs before ingestion of the causative food may alleviate symptoms.[7] Herein, antihistamine and injectable epinephrine were prescribed prophylactically to help the patient control any accidental onset in the future.

PFAS can be diagnosed easily once the food-causing symptoms are identified. However, guiding the diagnosis can be challenging if the patient is unaware of food allergies. When encountering widespread erosion in the oral cavity, it is essential to keep PFAS in mind.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

- 1.Amlot PL, Kemeny DM, Zachary C, Parkes P, Lessof MH. Oral allergy syndrome (OAS): Symptoms of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to foods. Clin Allergy. 1987;17:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1987.tb02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausukua M, Dublin I, Echebarria MA, Aguirre JM. Oral allergy syndrome (OAS). General and stomatological aspects. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:e568–72. doi: 10.4317/medoral.14.e568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondo Y, Urisu A. Oral allergy syndrome. Allergol Int. 2009;58:485–91. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.09-RAI-0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortolani C, Pastorello EA, Farioli L, Ispano M, Pravettoni V, Berti C, et al. IgE-mediated allergy from vegetable allergens. Ann Allergy. 1993;71:470–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebisawa M, Ito K, Fujisawa T. Committee for Japanese pediatric guideline for food allergy, the Japanese society of pediatric allergy and clinical immunology, Japanese society of allergology. Japanese guidelines for food allergy 2020. Allergol Int. 2020;69:370–86. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cianferoni A. Non-IgE mediated food allergy. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2020;16:95–105. doi: 10.2174/1573396315666191031103714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muluk NB, Cingi C. Oral allergy syndrome. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2018;32:27–30. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2018.32.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueroa J, Blanco C, Dumpiérrez AG, Almeida L, Ortega N, Castillo R, et al. Mustard allergy confirmed by double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges: Clinical features and cross-reactivity with mugwort pollen and plant-derived foods. Allergy. 2005;60:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holst B, Williamson G. A critical review of the bioavailability of glucosinolates and related compounds. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:425–47. doi: 10.1039/b204039p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]