Visual Abstract

Abstract

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders characterized by activated Janus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling. As a result, JAK inhibitors have been the standard therapy for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis (MF). Although currently approved JAK inhibitors successfully ameliorate MPN-related symptoms, they are not known to substantially alter the MF disease course. Similarly, in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera, treatments are primarily aimed at reducing the risk of cardiovascular and thromboembolic complications, with a watchful waiting approach often used in patients who are considered to be at a lower risk for thrombosis. However, better understanding of MPN biology has led to the development of rationally designed therapies, with the goal of not only addressing disease complications but also potentially modifying disease course. We review the most recent data elucidating mechanisms of disease pathogenesis and highlight emerging therapies that target MPN on several biologic levels, including JAK2-mutant MPN stem cells, JAK and non-JAK signaling pathways, mutant calreticulin, and the inflammatory bone marrow microenvironment.

Our knowledge about the biology of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) has exploded in the last 20 years, and this increased knowledge has led to advances in therapy. Introduced by Associate Editor Mario Cazzola, this Review Series brings readers up to date on our understanding of the natural history of the classical MPNs—polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myelofibrosis—and the approaches to diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment for patients with these conditions.

Introduction

Philadelphia chromosome–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) including polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and myelofibrosis (MF) are chronic blood cancers characterized by an excessive production of mature blood cells of the myeloid lineage. In more than 90% of the cases, MPNs develop because of the acquisition of an MPN phenotypic driver mutation in 1 of 3 genes: JAK2, CALR, or MPL, with the resultant activations of Janus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling.1,2 Current treatment for PV and ET is largely focused on reducing the risk of thrombosis, with cytoreduction indicated for those patients deemed to be at high risk. Older age (>60 years), prior history of thrombosis, presence of the JAK2V617F mutation, and coexisting cardiovascular risk factors are all considered to be factors associated with increased thrombotic risk. In contrast, mutations in CALR have been demonstrated to confer lower risk of thrombosis,3 and patients with type 1 CALR-mutated MF also have better leukemia-free and overall survival than those with JAK2- or MPL-mutated MF.4 Although ruxolitinib was reported to confer an overall survival advantage in a pooled analysis of the COMFORT trials,5 current treatments in MF are largely palliative to reduce symptom burden, blood counts, and spleen size, with no therapies known to alter the disease course substantially, except for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation.

However, greater understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying MPN pathogenesis have led to more rationally designed therapies, including interventions that may result in disease modification.6 Clinical trials have primarily been focused on MF, where prognosis and complications are often more grave, but novel treatments are also being evaluated in ET and PV. Here, we review the most recent data elucidating mechanisms of disease in MPNs, with a focus on those with therapeutic potential. This review will not cover MPN-related thrombosis or stem cell transplantation, both of which have been reviewed elsewhere.7,8

MPNs are HSC disorders

Understanding of the pathophysiology of MPNs was transformed after the discovery in 2005 that mutations in JAK2, specifically the JAK2V617F mutation, were found in nearly all patients with PV and in ∼50% to 60% of patients with ET and MF.9, 10, 11, 12 It was subsequently established that the JAK2V617F mutation arises in the long-term HSC compartment, consistent with the fact that it can be detected in both myeloid and lymphoid lineage cells.13, 14, 15 Similarly, CALR and MPL mutations have also been found to occur in multipotent HSCs.16,17 Although sequencing studies in humans1,18 and multiple MPN mouse models19, 20, 21 have shown that an MPN phenotypic driver mutation alone is sufficient to cause a full MPN phenotype, the JAK2V617F mutation can be detected in asymptomatic individuals as clonal hematopoiesis, indicative of a preclinical phase of disease.22 Consistent with this, 2 independent studies have recently shown evidence for a long latency period between JAK2V617F mutation acquisition and MPN presentation.23,24 Through whole-genome sequencing of HSCs, Williams et al and Van Egeren et al performed phylogenetic reconstruction of clonal lineage histories in patients with JAK2-mutated MPNs.23,24 Both groups found that the JAK2 mutation arose decades before disease presentation, and in some cases was acquired in utero, with a mean latency between mutation acquisition and disease presentation of ∼30 years. Similar findings were recently reported for CALR-mutant MPN, in which monozygotic twins presented at ages 37 and 38 with MF. Using whole-genome sequencing and lineage tracing, the authors identified a common in utero origin for the CALR-mutant clone, with twin-to-twin transplacental transmission and subsequent MPN development in adulthood.25 A recent study using mathematical modeling to infer disease initiation in patients with CALR and JAK2 mutation found that, in general, CALR mutations are acquired later in life and have a stronger HSC growth advantage than JAK2 mutations.26 This is consistent with a younger age of MPN onset in patients with CALR mutation than in those with JAK2 mutation27 and the finding that the CALR-mutant variant allele fraction (VAF) measured in granulocytes is typically 40% to 50% at the time of ET diagnosis,28 suggesting that heterozygous CALR-mutant HSC quickly become clonally dominant. Following acquisition of an MPN phenotypic driver mutation, the subsequent clonal expansion of the HSC-mutated clone is likely influenced by additional factors, including germ line factors,29 occurrence of other mutations in a particular order,30,31 inflammation,32,33 and the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment.34,35 These recent findings reframe MPNs as a chronic disease with a long precursor state, in which the disease presentation is a late phase and fit clones have reached a detectable level that results in symptoms. Given the lifelong trajectories of MPNs, one wonders if the current treatment paradigm for ET and PV, in which therapies are targeted at reducing vascular risk and low-risk patients are often observed, should shift to earlier interventions.

Targeting the HSC compartment is an appealing approach, given that it would eradicate disease at its source. This, however, has been challenging given that long-term HSCs are generally resistant to therapeutic targeting, likely because of their quiescent state. It is also difficult to identify therapeutic targets unique to the MPN stem cell that spare healthy HSCs and leave them unaffected. Among current MPN therapies, interferons are notable for their capacity to induce durable molecular responses. In addition, interferons have a long history of clinical efficacy in MPNs, particularly in patients with ET and PV.36,37 Although the mechanism of action of interferons is multifactorial, molecular responses observed in patients with JAK2-mutant MPN treated with pegylated interferons are likely due to the differential effects of interferon on JAK2-mutated HSCs over healthy HSCs.

Mechanism of action of interferons and targeting of HSCs

There has been a resurgence of interest in interferons as treatment for MPNs, given clinical data indicating that interferons can reduce the JAK2V617F mutant allele burden and, in some cases, even induce complete molecular remission.38,39 In mice, it has been shown that interferon induces HSC exit from quiescence and differentiation into mature progenitors, resulting in preferential depletion of JAK2-mutated HSCs,40,41 a finding that has also been validated in human MPNs42,43 (Figure 1A). Using JAK2V617F mouse models and patient samples, Rao et al found that prolonged interferon stimulation preferentially induced expansion of a megakaryocyte-biased CD41Hi HSC subset at the expense of more primitive CD41Lo populations.44 Because CD41Hi subsets have less self-renewing capabilities, this biased expansion could result in the eventual exhaustion of MPN-sustaining HSCs. Treatment with interferons has also been shown to result in accumulation of reactive oxygen species and induction of DNA damage preferentially in JAK2-mutant HSCs in mice.45 Interestingly, molecular responses are distinct in patients with JAK2- vs CALR-mutated MPNs.46 Sequential next-generation sequencing of patients treated with pegylated interferons, in the DALIAH trial, showed that patients with a JAK2 mutation had a significant reduction in VAF at 24 months in response to interferon, whereas patients with a CALR mutation did not,46 consistent with retrospective data and a more recent prospective observational study showing that CALR-mutant progenitor cells are less responsive to interferon than JAK2-mutant progenitors.43,47 Overall, hematologic responses with hydroxyurea and pegylated interferon were similar in both the DALIAH and MPN-RC 112 randomized phase 3 trials, which may be partially because of the high discontinuation rates observed in those who experienced pegylated interferon-related toxicity. However, greater decreases in JAK2V617F VAF were observed with longer treatment duration of pegylated interferon.46,48 Notably, treatment-emergent DNA-methyltransferase-3α (DNMT3A) mutations were identified in patients treated with interferons in the DALIAH trial, highlighting the importance of assessing molecular response not just in MPN phenotypic driver mutations, but more broadly, using sequential genomic profiling because divergent molecular responses may occur in independent clones or subclones in the same patient.46

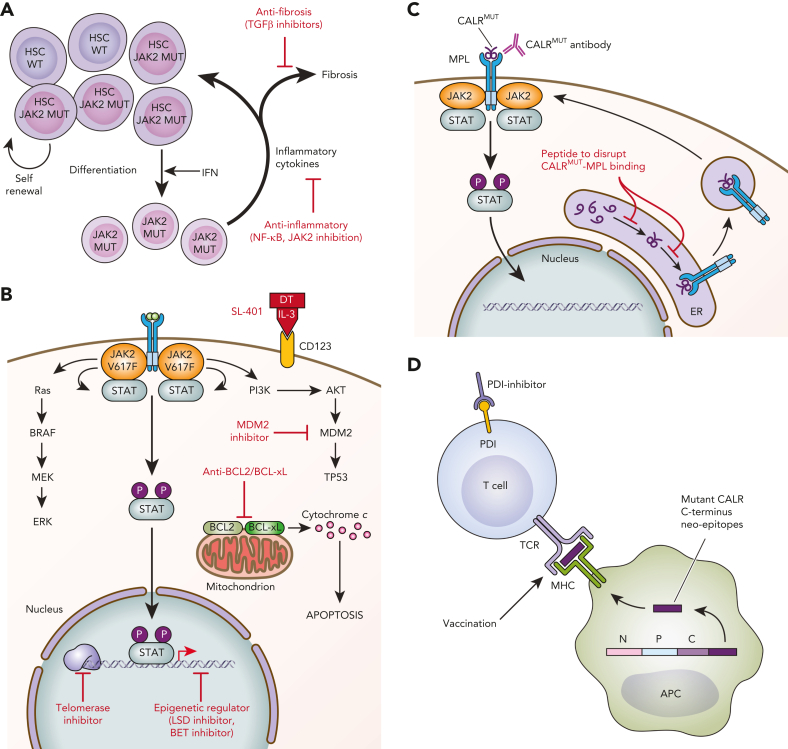

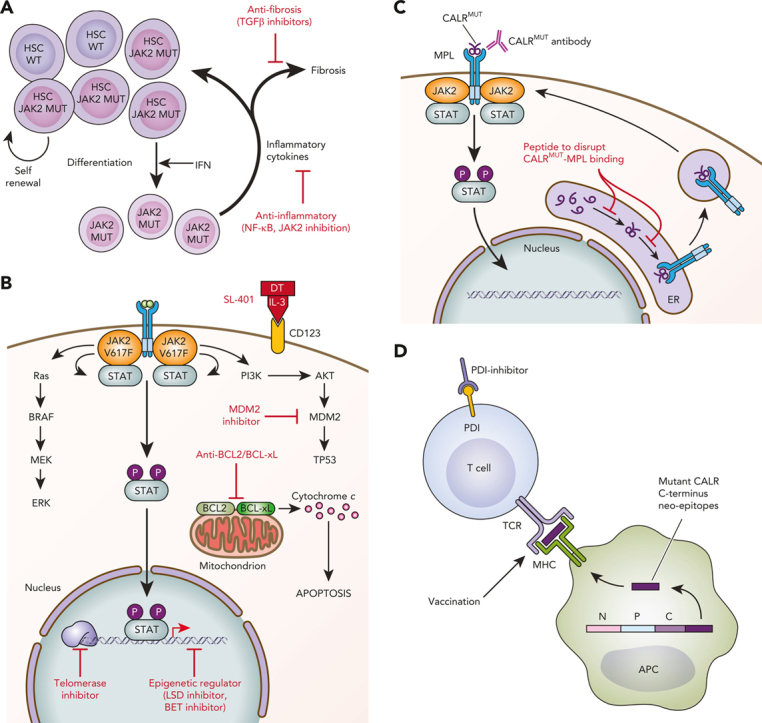

Figure 1.

Schematic of novel therapies in development for the treatment of MPNs. (A) Targeting the HSC and microenvironment. JAK2V617F–mutated HSCs show clonal dominance over wild-type HSCs. Interferon preferentially targets JAK2-mutated HSCs to induce exit from quiescence and promote terminal myeloid differentiation, resulting in preferential depletion of JAK2-mutated HSCs. The expanded myeloid clone also disrupts the BM microenvironment through secretion of inflammatory mediators. Novel therapies targeting inflammation and profibrotic cytokines may delay or prevent the progression of early MPNs to MF. (B) Targeting cell signaling, epigenetics, and apoptosis. MPNs are characterized by activated JAK/STAT signaling. Multiple signaling pathways are activated downstream of mutant JAK2 and represent targets for therapeutic intervention. (C) Novel therapies targeting CALR-mutated MPNs. Novel therapies in preclinical development against CALR-mutated MPNs include antibodies to block mutant CALR on the cell surface and peptides to disrupt intracellular MPL/mutant CALR binding. (D) Immune therapies targeting CALR-mutated MPNs. Vaccination strategies to induce T-cell–directed immune activation against CALR-mutated clones take advantage of the mutant CALR C-terminus neoepitopes generated by CALR mutations. APC, antigen-presenting cell; DT, diphtheria toxin; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; IFN, interferon; MUT, mutated; P, phosphorylated; TCR, T-cell receptor; WT, wild-type. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

There have been ongoing efforts to improve existing interferon treatments in MPNs. The development of ropeginterferon, a monopegylated form of interferon with improved tolerability, has demonstrated superior hematologic and molecular responses than the use of hydroxyurea in patients with PV, although superior molecular responses only became apparent at 2 years.49 The slow rate of molecular responses is partially because of the fact that titration of ropeginterferon to therapeutic dosing takes more than 6 months. However, sustained JAK2V617F molecular responses to ropeginterferon have been reported at 5 years.50 Ropeginterferon is now approved in the United States and Europe for patients with PV in the frontline setting, regardless of risk status.

Identification of the downstream pathways that potentiate or bypass interferon response signaling may also lay the groundwork for combination therapies that improve interferon’s efficacy. For instance, promyelocytic protein (PML) is a tumor suppressor that is important in the induction of senescence and programmed cell death. PML is a target of arsenic trioxide (ATO) and is transcriptionally activated by interferons.51 In experimental studies, ex vivo treatment with ATO potentiated interferon-induced growth suppression in JAK2V617F progenitor cells and the combination of ATO with interferon enhanced hematologic and molecular responses in MPN mouse models compared with ATO or interferon alone.52 Unc-51–like kinase 1 (ULK1) has been identified as a mediator of interferon’s effects against clonal progenitor cells in MPNs. Interferon treatment activates ULK1-interacting Rho-associated kinases (ROCK1/2) resulting in a negative feedback loop suppressing interferon responses,53 suggesting that combining ROCK inhibition with interferon may enhance treatment response in MPNs. Interferon activity has also been studied in combination with ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor. Although ruxolitinib antagonizes interferon-induced JAK1 signaling, the favorable activity of both treatments in MPNs can be retained with combination therapy. It has been shown that JAK/STAT pathway activation is enhanced with chronic interferon stimulation in JAK2V617F mouse models, and ruxolitinib therapy does not inhibit interferon-induced reactive oxygen species and DNA damage to JAK2V617F HSCs.45 A phase 2 trial of ruxolitinib and pegylated interferon showed improvements in cell counts in 32 patients with PV and 18 with MF, although it was met with significant toxicity, particularly in patients with MF (32% discontinuation rate).54

JAK2 inhibition in MPNs

The JAK2V617F mutation lies within the pseudokinase domain of JAK2, which sits adjacent to its C-terminal tyrosine kinase domain. A crystal structure of the JAK2 pseudokinase domain harboring the JAK2V617F mutation was solved in 2012, and in 2022 the full-length structure of a homologous JAK mutant (JAK1V657F), complexed with a cytokine receptor intracellular domain, was revealed using cryo-electron microscopy.55,56 This recent study advances the understanding of the basis for JAK dimeric activation, in the context of a V617F homologous mutant. Efforts to develop JAK2V617F-selective inhibitors are ongoing, but none have yet advanced to clinical testing.

Current JAK2 inhibitors

Currently approved JAK2 inhibitors are not strongly clonally selective for the JAK2-mutant clone and act as competitive inhibitors on the adenosine triphosphate–binding site. Ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, was first approved in patients with MF and later in those with PV who were refractory or intolerant to hydroxyurea.57, 58, 59 Since ruxolitinib, there have been 2 additional Food and Drug Administration–approved JAK2 inhibitors for the treatment of MF. Fedratinib is a JAK2 and fms-like tyrosine kinase (FLT3) inhibitor that can be used as an alternative first- or second-line agent for MF.60 Both ruxolitinib and fedratinib are limited by treatment-related adverse effects including cytopenias and are not recommended for use in patients with platelet counts <50 × 109/L. Pacritinib, a JAK2, FLT3, and interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) inhibitor, was the third JAK2 inhibitor approved in MF and its label allows use in patients with baseline platelet counts <50 × 109/L, based on the results of the PAC203 dose-finding and phase 3 PERSIST-1 and 2 trials.61, 62, 63, 64 Finally, since IRAK1 is also involved in inflammatory signaling pathways that may promote fibrotic progression,35 inhibiting IRAK1 in MF may provide additional benefit.

Because one of the on-target toxicities of JAK2 inhibition is anemia, several JAK2 inhibitors worsen anemia, which is a common feature in MF. Anemia in MF is multifactorial and partially due to the inflammatory milieu in MF, and upregulation of hepcidin is associated with worsened anemia of inflammation.65 Momelotinib is a selective inhibitor of JAK1, JAK2, and activin receptor type 1 (ACVR1), the latter of which is a transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) family member that controls iron storage and upregulates hepcidin. Inhibition of ACVR1 leads to decreased hepcidin production, allowing mobilization of sequestered iron and improved markers of erythropoiesis.66 In patients with upfront intermediate-2/high-risk MF, momelitinib was associated with reduced transfusion requirements compared with ruxolitinib in the phase 3 SIMPLIFY-1 trial and was noninferior to ruxolitinib for spleen response but not for symptom response.67 Recently presented data from the phase 3 MOMENTUM study among patients with MF previously treated with ruxolitinib demonstrated the superiority of momelitinib to danazol in symptom improvement and spleen reduction and noninferiority in transfusion independence. Though danazol is a supportive agent recommended by expert consensus guidelines,68 it might have been a weak comparator arm because danazol is not expected to induce significant spleen or symptom responses in patients with MF.69

Novel approaches to targeting JAK2V617F

Although JAK2 inhibitors represent a major step forward in the treatment of MPNs, they do not significantly decrease the JAK2- or CALR-mutant clonal burden, and with prolonged treatment, clinical resistance inevitably develops.70,71 Concordant with this, JAK2 inhibitor resistance appears to be mediated by nonmutational mechanisms, suggesting that a strong selective pressure is not exerted on the JAK2-mutant clone in patients treated with JAK2 inhibitors (ie, mutations in JAK2 kinase domain are not observed).72 Advancement in the knowledge of JAK2V617F dimeric activation, as outlined here, continues to drive an interest in developing JAK2V617F-mutant–specific inhibitors.56 Conditionally inducible JAK2V617F mouse models in which JAK2V617F expression can be switched off and the MPN phenotype is reversed support this approach.73,74 Type II JAK2 inhibitors that bind JAK2 in an inactive conformation have been developed and reported to show enhanced selectivity for mutant JAK2 in preclinical models.75,76 Targeting ubiquitination and degradation of mutated JAK2 is another novel approach to JAK2 inhibition currently under investigation, including design of proteolysis-targeting chimeras that degrade oncogenic JAKs and inhibition of deubiquitinases that stabilize the JAK2V617F protein.77,78

Non-JAK2 targets in MPNs

Given the limitations of JAK2 inhibition, particularly in MF, there is an ongoing effort to develop several non-JAK2 inhibitors and regimens in combination with JAK2 inhibitors to increase pathway inhibition or to address MPN clones that are not JAK2 dependent. An in-depth overview of all novel inhibitors being investigated in the treatment of MPNs is outside the scope of this review, however, we highlight some promising therapies here. Table 1 also summarizes drugs with clinical data and known plans for future development.

Table 1.

Summary of selected drugs approved or in clinical development for MPNs

| MF | Mechanism | Trial | Clinical response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rux57,58 (approved) | JAK2 inhibitor | 3 | SVR35 = 42% TSS50 = 50% |

| Fedratinib79 (approved) | JAK2 inhibitor | 3 Rux naïve |

SVR35 = 37% TSS50 = 40% |

| 2 Prior rux |

SVR35 = 55% TSS50 = 26% |

||

| Pacritinib61 (approved) | JAK2 inhibitor | 3 Prior rux allowed Platelets <100 × 109/L |

SVR35 = 29% TSS50 = 32% |

| Momelitinib67 | JAK2 inhibitor | 3 Rux naïve |

SVR35 = 27% TSS50 = 38% Transfusion independence at wk 24 in 67% |

| AVID20080 | TGF-β trap | 1B (N = 21) Prior rux |

SVR35 = 19% TSS50 = 43% 3/4 patients treated to cycle 12 with clinical improvement |

| Bomedemstat81 | LSD1 inhibitor | 1/2 (N = 89) Prior rux |

SVR35 = 37% TSS50 = 39% BM fibrosis improvement in 17% |

| Imetelstat82 | Telomerase inhibitor | 2 (N = 59) Prior rux |

SVR35 = 10% TSS50 = 32% BM fibrosis improvement in 40.5% |

| Navtemadlin83 | MDM2 inhibitor | 2 (N = 32∗) Prior rux |

SVR35 = 16% TSS50 = 30% BM fibrosis improvement in 27% |

| Navitoclax + rux84 | BCL2 inhibitor | 2 (N = 34) | SVR35 = 27% TSS50 = 30% Anemia response in 64% BM fibrosis improvement in 33% |

| Parsaclisib + rux85 | PI3K inhibitor | 2 (N = 51) | SVR35 = 27% TSS50 = 50% |

| Pelabresib86 | BET inhibitor | 2 (N = 86) | SVR35 = 11% TSS50 = 28% TD to TI conversion rate in 16% BM fibrosis improvement in 23.4% |

| Pelabresib + rux87 | BET inhibitor | 2 (N = 78) Rux naïve |

SVR35 = 67% TSS50 = 57% BM fibrosis improvement in 33% |

| 2 (N = 70) Prior rux |

SVR35 = 21% TSS50 = 53% TD to TI conversion rate 36% |

||

| Selinexor88 | Selective inhibitor of nuclear export | 2 (N = 10) | SVR35 = 30% Reduction in TSS in 8 evaluable patients |

| Tagraxofusp89 | CD123 (IL-3Rα) targeted therapy (recombinant human IL-3 fused to diphtheria toxin) | 1/2 (N = 39) | SVR10 = 47%; SVR50 = 29% TSS50 = 36% |

| PV/ET | |||

| Pegylated interferon46,48 | Interferon | 3 | CHR: 35% at 1 y; 21% at 2 y MR: 16% at 18 mo |

| Ropeginterferon49 | Interferon | 3 | CHR: 43% at 1 y; 48% at 2 y; 54% at 3 and 4 y MR: 34% at 1 and 2 y; 50% at 3 and 4 y |

| Rusfertide90,91 | Hepcidin mimetic | 2 (N = 63) PV |

Mean phlebotomy after enrollment: 0.43 (vs 4.63 prior) |

| Bomedemstat92 | LSD1 inhibitor | 2 (N = 29) ET |

TSS50 = 53% 100% with normalization of platelet counts |

CHR, complete hematologic response; IL-3, interleukin 3; IL-3Rα, interleukin 3 receptor α; MR, molecular response; rux, ruxolitinib; SVR10/35/50, spleen volume reduction by 10%/35%/50% (shown are observations at week 24); TD, transfusion dependence; TI, transfusion independence; TSS50, total symptom score improvement by 50%.

Sample size of cohort receiving dosing selected for phase 3 testing; response rates are reported for this cohort.

Targeting signaling pathways

Multiple signaling pathways are activated in MPNs and contribute to disease progression and failure of JAK2 inhibition. These pathways include phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin93 and extracellular signal-regulated kinases/mitogen-activated protein kinase 94,95 (Figure 1B), providing rationale for combination therapies with ruxolitinib. Positive phase 2 data for the PI3Kδ inhibitor parsaclisib in combination with ruxolitinib in patients with MF with suboptimal responses to ruxolitinib have been reported in abstract form (Table 1)85 and are the basis for ongoing phase 3 studies in the first-line (#NCT04551066) and second-line (#NCT04551053) settings.

Targeting antiapoptosis pathways

JAK/STAT signaling pathway activation and resistance to JAK inhibitors also provide opportunities for targeting antiapoptotic pathways.96,97 Antiapoptotic proteins including BCL-2, BCL-xL, and MCL-1 sequester proapoptotic BCL-2 homology 3 (BH3)–only proteins by binding to their BH3 motifs, thereby preventing the initiation of apoptosis.96 Small molecules targeting these antiapoptotic proteins have been developed to trigger apoptosis by binding these proteins, freeing proapoptotic proteins, and promoting apoptosis.96 Functional dissection of the critical survival pathways in human and mouse models bearing JAK2-mutated leukemias revealed upregulation of prosurvival (antiapoptotic) Bcl-2 family genes, dependence on BCL-2/BCL-xL, and the ability to overcome JAK2 inhibitor-acquired resistance with combined targeting of JAK2 and BCL-2/BCL-xL98 (Figure 1B). Gain-of-function studies in JAK2V617F-mutated MPNs identified resistance to JAK inhibition upon activation of RAS and its effector pathways, which results in dependence on BCL-xL for survival.97 Navitoclax (ABT-263) is an orally bioavailable BH3 mimetic that binds with high affinity to prosurvival BCL-xL, BCL-2, and BCL-W. Preclinical data indicate synergistic activity of combination JAK2 inhibition and navitoclax.99 The REFINE phase 2 trial (n = 34) demonstrated safety and clinical activity with the addition of navitoclax to ongoing ruxolitinib in patients with persistent or progressive MF (Table 1).84 An exploratory study provided preliminary evidence for BM fibrosis grade reduction in approximately one-third of patients with MF that received combination navitoclax and ruxolitinib, regardless of high-molecular risk mutation status, and reduction of ≥20% in driver VAF, suggesting disease modifying benefits as these treatment-induced biological changes were associated with increased survival.100 Results from the ongoing phase 3 trials in the upfront (TRANSFORM-1) and relapsed/refractory (TRANSFORM-2) settings are awaited.

Targeting epigenetic regulators: BET and LSD1

Epigenetic dysregulation is a feature of MPNs, and mutations in genes involved in DNA methylation (eg, TET2, DNMT3A, and IDH1/2) and chromatin modification (eg, ASXL1 and EZH2) are frequently found.1 In the context of MF, IDH1/2, ASXL1, and EZH2 mutations are defined as high-molecular risk mutations and associated with adverse prognosis.101 Although ASXL1 and EZH2 mutations are associated with decreased response to JAK inhibitor therapy,102,103 there are currently no rationally designed approaches to directly target mutant ASXL1 or EZH2. Except for small molecule inhibitors of mutant IDH1/2, current therapies targeting epigenetic regulators in MPN exert their effects indirectly.

NF-kB signaling is activated in MF and contributes to the proinflammatory state that characterizes MPNs and may drive the development of fibrosis. The bromodomain and extraterminal domain (BET) family of proteins bind to acetylated histones, facilitating transcription of genes regulated by NF-kB.104 Preclinical work by Kleppe et al has demonstrated that dual JAK/BET inhibition results in the reduction of inflammatory cytokines and BM fibrosis in MPN mouse models.104 Data from studies on mice suggest that EZH2 and ASXL1 mutations can sensitize MF-initiating cells to BET inhibition.105,106 Pelabrisib, a first-in-class oral BET inhibitor, is currently being evaluated in the phase 2 MANIFEST study as a single agent and in combination with ruxolitinib, both in the upfront and refractory setting (#NCT04603495) (Table 1 and Figure 1B).87

LSD1 is a histone demethylase important for regulating HSC self-renewal and proliferation through the epigenetic regulation of gene transcription. LSD1 activity is essential for enhancer silencing during cell differentiation and in myelopoiesis.107 LSD1 allows myeloid progenitors to differentiate into mature myeloid lineage cells.108 In a conditional in vivo knockdown mouse model of LSD1, loss of LSD1 resulted in an extensive expansion of myeloid progenitor cells with a concomitant severe inhibition of terminal granulopoiesis, erythropoiesis, and platelet production, with reversal of the cytopenias upon knockdown termination.109 Increased LSD1 expression has been reported in MPNs, mainly in megakaryocytes.110 LSD1 inhibition in MPN mouse models resulted in reduced blood counts and spleen volume, improved BM fibrosis, and increased survival.111 In human MPNs, results of monotherapy with bomedemstat, an oral LSD1 inhibitor, have been reported in abstract form for both patients with MF and ET in phase 1/2 clinical trials (Table 1), with reduced splenomegaly and symptoms observed in MF and reduction in platelet counts observed in ET (Figure 1B).81,112 The impact of LSD1 inhibition on myeloid differentiation in human MPN BM has not yet been reported from these clinical trials; this will be an important parameter to follow given that loss of LSD1 in normal murine hematopoiesis results in an expansion of myeloid progenitor cells by blocking myeloid differentiation.109 Interestingly, LSD1 inhibitors have been reported to induce myeloid differentiation in MLL-translocated acute myeloid leukemia, a mechanism initially thought to result from blocking LSD1 demethylase activity but more recently reported to be a consequence of disrupting the LSD1-GFI1B interaction on chromatin.113, 114, 115

Other targets: MDM2 pathway, telomerase inhibition, and cell cycle

Other non-JAK inhibitor therapies currently in development for MPNs include the mouse double-minute homolog 2 (MDM2) inhibitor, which exerts its mechanism of action by restoring the TP53 pathway (Figure 1B).116 Gastrointestinal toxicities seen with this drug limit its future clinical development for PV and ET, although it is being evaluated in the relapsed or refractory setting in patients with MF with TP53 wild-type disease after JAK inhibitor failure (#NCT03662126) (Table 1). Increased telomerase activity and shortened telomeres are seen in MPNs, and telomerase inhibition results in the selective reduction of clonal megakaryocyte colony-forming units in MF and ET.117 A randomized, phase 2 trial of imetelstat, a telomerase inhibitor (Figure 1B), was completed in patients with intermediate-2/high-risk MF who were relapsed or refractory to ruxolitinib and demonstrated clinical improvements, including spleen and symptom responses at the higher dose and reduction of BM fibrosis in 40.5% and driver VAF in 42.1% of the patients (Table 1).82 At the recommended phase 2 dose, a median overall survival of 29.9 months was observed. A phase 3 trial (#NCT04576156) is currently underway. There are also data indicating that cell cycle genes regulated by activated JAK/STAT signaling promote MPN disease.118 Preclinical studies evaluating combination CDK4/6 inhibitors with ruxolitinib in mice show improvements in disease phenotypes.119 The addition of inhibitors of proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase (PIM1), also a cell cycle regulator, to ruxolitinib and CDK4/6 inhibitors similarly reduces disease features in MPN mouse models.120

Targeting hepcidin and altered iron metabolism in PV

A novel approach, rationally designed based on preclinical studies, is the development of hepcidin mimetics in PV, with the goal of constraining mutant JAK2-driven erythrocytosis, and thus reducing/eliminating the need for therapeutic phlebotomy. Unlike in MF, in which increased hepcidin levels contribute to an inflammatory anemia, in PV, there is relative suppression of hepcidin without mobilization of hepatic iron stores or increased iron absorption.121 As a result, patients with PV often show evidence of iron deficiency even before therapeutic phlebotomy is initiated, including lower serum iron, ferritin, and transferrin saturation.121 Hepcidin mimetics provide a chemical therapeutic phlebotomy, with the goal of restricting iron for accelerated erythropoiesis while reducing systemic iron deficiency. Mini-hepcidin mimetics normalized splenomegaly and hematocrit levels in JAK2V617F–mutated mouse models of PV,122 and in phase 2 trials, the hepcidin mimetic rusfertide (PTG-300) similarly reduced hematocrit levels and therapeutic phlebotomy needs in patients with PV.90 A phase 3 trial evaluating rusfertide vs placebo in patients with PV requiring frequent phlebotomy is currently underway (#NCT04057040 and #NCT04767802).

CALR-mutated MPNs provide novel therapeutic targets

Approximately 80% of patients with ET and MF without JAK2 mutations will have mutations in CALR.16,123 CALR encodes for calreticulin, an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein. MPN-associated CALR mutations are insertions and/or deletions in exon 9 that induce a frameshift, resulting in the generation of a novel positively charged C-terminus to the mutant CALR protein. This mutant-specific C-terminus of mutant CALR enables pathogenic binding with MPL, ultimately resulting in ligand-independent MPL/JAK/STAT signaling pathway activation124, 125, 126, 127 (Figure 1C). The specific requirements for the interaction of mutant CALR with MPL have revealed potential opportunities for therapeutic targeting. For instance, mutant CALR forms homomultimers to bind and activate MPL.128 Zinc is a cofactor necessary for mutant CALR homomultimerization, and ex vivo treatment with zinc chelators disrupted CALRdel52-MPL signaling complexes in CALR-mutated cells, identifying the reduction in intracellular zinc levels as a potential treatment approach in CALR-mutated MPNs.129 N-glycosylation of the extracellular domain of MPL and the lectin-binding sites of mutant CALR are also required for the mutant CALR-MPL interaction.127,130,131 Whole-genome CRISPR screening recently identified N-glycosylation as a therapeutic vulnerability in mutant CALR-transformed hematopoietic cells, and chemical inhibition of N-glycosylation resulted in an improvement of disease features in CALR-mutant mouse models and reduced growth of CALR-mutant patient-derived BM in vitro.132 Other approaches tested in the preclinical setting include (1) delivering a wild-type CALR C-terminal synthetic peptide that is taken up by the cell with the goal of abolishing the intracellular mutant CALR binding interaction with MPL (Figure 1C) and (2) targeting the inositol requiring enzyme 1a (IRE1a)/X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) axis of the unfolded protein response, since CALR is an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone.133, 134, 135

CALR-mutated MPNs also provide unique opportunities for immunologic treatment strategies given that the novel mutated C-terminus is tumor specific. Because the mutant CALR-MPL complex traffics to the cell surface, interest in therapeutically targeting mutant CALR using a mutant CALR blocking antibody (Figure 1C) has grown. Three recent studies reported the development and testing of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies targeting the C-terminal mutant CALR sequence in preclinical models,136, 137, 138 with 1 of the studies also testing the antibody (4D7) against primary MPN cells in vitro and demonstrating reduced megakaryocyte proliferation, specifically in CALR-mutant (but not JAK2-mutant) cells.136 Similar findings in primary MPN cells were recently reported for a fully human immunoglobulin G1–mutant CALR antibody (INCA033989) as a plenary abstract at the 2022 American Society of Hematology meeting.139 In addition, using a chimeric mutant CALR BM transplant model, the authors reported that treatment with INCA033989 selectively targeted CALR-mutant platelets, megakaryocytes, and long-term HSCs. In aggregate, these preclinical studies indicate that therapeutic mutant CALR antibodies have specificity and efficacy, and further clinical development is awaited.

Using in silico approaches, it has been shown that the mutant-specific C-terminus of mutant CALR is predicted to generate multiple neoepitopes that bind to major histocompatibility class I (MHC-I) with high affinity.140 This has led to interest in developing T-cell receptor–mediated immune therapy, including vaccination approaches (Figure 1D). However, peptide-stimulated T-cell responses against mutant CALR epitopes are decreased in patients with MPN compared with those in healthy control subjects, suggesting defects in immune response and/or antigen presentation in MPN.141 Consistent with this, T cells from patients with MPN exhibit an exhausted phenotype with increased expression of immune checkpoint receptors,142 and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitor monotherapy failed to show clinical responses in a phase 2 single-arm study.143 Although it has not been directly demonstrated that mutant CALR–derived neoepitopes are presented by MHC-I,144 indirect evidence suggests that they are. MHC-I alleles predicted to bind to CALR-mutated neoepitopes with high affinity are underrepresented in patients with CALR-mutant MPN (as compared with patients with JAK2-mutant MPN and population-matched healthy control subjects). This suggests that immune-mediated clearance by individuals expressing a mutant CALR neo-epitope high-affinity binding MHC-I allele occurs such that CALR-mutant MPN may not manifest clinically in these individuals.140 In the first vaccine trial with a mutant CALR peptide, none of the 10 patients had any clinical response and only 2 had a CD8+ T-cell response, consistent with impaired MHC processing and/or presentation of neoepitope antigens.145 Alternative approaches to enhance the mutant CALR-directed T-cell immune response include the use of a modified vaccine approach, such as heteroclitic peptides, which optimize MHC-I binding affinity,140 or combination approaches with an MPN-directed neoantigen vaccine plus an immune checkpoint inhibitor, which is the focus of a recently opened phase 1 clinical trial (#NCT05444530).

The inflammatory microenvironment promotes MPN progression

The BM microenvironment and, in particular, the development of fibrosis are key aspects of disease pathophysiology in MF. The cell nonautonomous effects of the MPN clone on the BM niche via the release of inflammatory mediators are central to the pathogenesis of myelofibrotic transformation.146 Notably, the physical properties of a fibrotic BM may also propagate a proinflammatory environment, which further establishes a self-reinforcing fibrotic niche.147 Nonclonal mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are thought to be a key MF-promoting cellular population within the BM niche, with recent studies implicating Gli1+ and Lepr+ MSCs as fibrosis-driving cells in the BM.35,148 Activation of the stroma by clonal MPN cells is likely driven by multiple inflammatory mediators; for example, an increased expression of CXCL4, a chemokine secreted by megakaryocytes, has been linked to progression of BM fibrosis and may be a potential drug target.33 TGF-β is also critical to MSC differentiation, with the loss of TGF-β signaling abrogating the development of MF in MPL and JAK2 MPN mouse models.149 Drugs targeting TGF-β, including TGF-β1–trap AVID-200, have therefore come under clinical investigation for the treatment of MF. Recently presented data demonstrated that, in patients with MF previously treated with ruxolitinib, AVID200 reduced TGF-β1 plasma levels and circulating inflammatory cytokines, although no reduction in BM fibrosis grade or cellularity was observed.80

Future directions

Although MPN encompasses a heterogenous and biologically complex set of chronic blood cancers, advances in understanding its molecular pathogenesis provide a framework toward developing improved treatments with the potential to target MPN disease–propagating stem cells. MPNs arise in the HSC compartment and have a long preclinical phase. MPN phenotypic driver mutations alone are sufficient to induce overt MPN. Increasing genomic complexity is observed with increased age and longevity of disease. The development of rationally designed therapies focused on targeting the clonal advantage conferred by MPN phenotypic driver mutations is likely to be clinically impactful, particularly if instituted in earlier stages of overt MPN or even in individuals with JAK2-mutant clonal hematopoiesis. An increased understanding of which individuals with JAK2-mutant clonal hematopoiesis are at the highest risk of developing overt MPN will help in designing clinical trials focused on MPN prevention. Continued efforts to uncover therapeutic vulnerabilities for high-molecular risk mutations associated with adverse prognosis and therapeutic resistance (eg, ASXL1, EZH2, SRSF2, U2AF1, and TP53) remain a high priority. The development of mutational-agnostic immunological therapies (eg, antibodies) offers the potential to overcome the therapeutic resistance of these mutations to currently available MPN therapies. Research advances enabling increasingly sophisticated studies of primary MPN tissues will continue to reveal new insights into MPN biology and uncover novel targets for therapeutic intervention.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.M. receives research funding from Relay Therapeutics; has consulted for Janssen, PharmaEssentia, Constellation, Aclaris, Cellarity, Morphic, Biomarin, Protagonist, and Incyte; has received research funding from Janssen and Actuate Therapeutics; and received a speaker honorarium from AOP Health. J.S.G. serves on advisory boards for AbbVie, Astellas, and Takeda; and has received institutional research funds from AbbVie, Genentech, Pfizer, Prelude, and AstraZeneca. J.H. declares no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Naveen Pemmaraju and Pankit Vacchani for sharing their presentations. The authors thank the patients and their families for participating in MPN-related research studies.

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL131835) (A.M.); Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (W81XWH2110909) (A.M.); and the Starr Cancer Consortium (I15-0026) (A.M.); and by research funding (K08CA245209) (J.S.G.).

Authorship

Contribution: All authors planned, wrote, and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Grinfeld J, Nangalia J, Baxter EJ, et al. Classification and personalized prognosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(15):1416–1430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rampal R, Al-Shahrour F, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. Integrated genomic analysis illustrates the central role of JAK-STAT pathway activation in myeloproliferative neoplasm pathogenesis. Blood. 2014;123(22):e123–133. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rotunno G, Mannarelli C, Guglielmelli P, et al. Impact of calreticulin mutations on clinical and hematological phenotype and outcome in essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2014;123(10):1552–1555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-538983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Finke CM, et al. CALR vs JAK2 vs MPL-mutated or triple-negative myelofibrosis: clinical, cytogenetic and molecular comparisons. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1472–1477. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verstovsek S, Gotlib J, Mesa RA, et al. Long-term survival in patients treated with ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis: COMFORT-I and -II pooled analyses. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0527-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pemmaraju N, Verstovsek S, Mesa R, et al. Defining disease modification in myelofibrosis in the era of targeted therapy. Cancer. 2022;128(13):2420–2432. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali H, Bacigalupo A. 2021 update on allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for myelofibrosis: a review of current data and applications on risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(11):1532–1538. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasselbalch HC, Elvers M, Schafer AI. The pathobiology of thrombosis, microvascular disease, and hemorrhage in the myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2021;137(16):2152–2160. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, et al. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James C, Ugo V, Le Couédic J-P, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(4):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamieson CH, Gotlib J, Durocher JA, et al. The JAK2 V617F mutation occurs in hematopoietic stem cells in polycythemia vera and predisposes toward erythroid differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(16):6224–6229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601462103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishii T, Bruno E, Hoffman R, Xu M. Involvement of various hematopoietic-cell lineages by the JAK2V617F mutation in polycythemia vera. Blood. 2006;108(9):3128–3134. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Tonetti C, et al. Evidence that the JAK2 G1849T (V617F) mutation occurs in a lymphomyeloid progenitor in polycythemia vera and idiopathic myelofibrosis. Blood. 2007;109(1):71–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-007146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nangalia J, Massie CE, Baxter EJ, et al. Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2391–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaligné R, James C, Tonetti C, et al. Evidence for MPL W515L/K mutations in hematopoietic stem cells in primitive myelofibrosis. Blood. 2007;110(10):3735–3743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundberg P, Karow A, Nienhold R, et al. Clonal evolution and clinical correlates of somatic mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2014;123(14):2220–2228. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-537167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullally A, Lane SW, Brumme K, Ebert BL. Myeloproliferative neoplasm animal models. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012;26(5):1065–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benlabiod C, Cacemiro MDC, Nédélec A, et al. Calreticulin del52 and ins5 knock-in mice recapitulate different myeloproliferative phenotypes observed in patients with MPN. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4886. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18691-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Prins D, Park HJ, et al. Mutant calreticulin knockin mice develop thrombocytosis and myelofibrosis without a stem cell self-renewal advantage. Blood. 2018;131(6):649–661. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-806356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2488–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Egeren D, Escabi J, Nguyen M, et al. Reconstructing the lineage histories and differentiation trajectories of individual cancer cells in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(3):514–523.e519. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams N, Lee J, Mitchell E, et al. Life histories of myeloproliferative neoplasms inferred from phylogenies. Nature. 2022;602(7895):162–168. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04312-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sousos N, M NL, Simoglou Karali C, et al. In utero origin of myelofibrosis presenting in adult monozygotic twins. Nat Med. 2022;28(6):1207–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01793-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hermange G, Rakotonirainy A, Bentriou M, et al. Inferring the initiation and development of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(37) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2120374119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rumi E, Pietra D, Pascutto C, et al. Clinical effect of driver mutations of JAK2, CALR, or MPL in primary myelofibrosis. Blood. 2014;124(7):1062–1069. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-578435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rumi E, Pietra D, Ferretti V, et al. JAK2 or CALR mutation status defines subtypes of essential thrombocythemia with substantially different clinical course and outcomes. Blood. 2014;123(10):1544–1551. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-539098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bao EL, Nandakumar SK, Liao X, et al. Inherited myeloproliferative neoplasm risk affects haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2020;586(7831):769–775. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez-Meira A, Buck G, Clark SA, et al. Unravelling intratumoral heterogeneity through high-sensitivity single-cell mutational analysis and parallel RNA sequencing. Mol Cell. 2019;73(6):1292–1305.e1298. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortmann CA, Kent DG, Nangalia J, et al. Effect of mutation order on myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):601–612. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleischman AG, Aichberger KJ, Luty SB, et al. TNFα facilitates clonal expansion of JAK2V617F positive cells in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;118(24):6392–6398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gleitz HFE, Dugourd AJF, Leimkühler NB, et al. Increased CXCL4 expression in hematopoietic cells links inflammation and progression of bone marrow fibrosis in MPN. Blood. 2020;136(18):2051–2064. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Decker M, Martinez-Morentin L, Wang G, et al. Leptin-receptor-expressing bone marrow stromal cells are myofibroblasts in primary myelofibrosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19(6):677–688. doi: 10.1038/ncb3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leimkühler NB, Gleitz HFE, Ronghui L, et al. Heterogeneous bone-marrow stromal progenitors drive myelofibrosis via a druggable alarmin axis. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(4):637–652.e638. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellucci S, Harousseau JL, Brice P, Tobelem G. Treatment of essential thrombocythaemia by alpha 2a interferon. Lancet. 1988;2(8617):960–961. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silver RT. Recombinant interferon-alpha for treatment of polycythaemia vera. Lancet. 1988;2(8607):403. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92881-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiladjian JJ, Cassinat B, Chevret S, et al. Pegylated interferon-alfa-2a induces complete hematologic and molecular responses with low toxicity in polycythemia vera. Blood. 2008;112(8):3065–3072. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quintás-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Manshouri T, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a yields high rates of hematologic and molecular response in patients with advanced essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5418–5424. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasan S, Lacout C, Marty C, et al. JAK2V617F expression in mice amplifies early hematopoietic cells and gives them a competitive advantage that is hampered by IFNα. Blood. 2013;122(8):1464–1477. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-498956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mullally A, Bruedigam C, Poveromo L, et al. Depletion of Jak2V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm-propagating stem cells by interferon-α in a murine model of polycythemia vera. Blood. 2013;121(18):3692–3702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-432989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King KY, Matatall KA, Shen CC, Goodell MA, Swierczek SI, Prchal JT. Comparative long-term effects of interferon α and hydroxyurea on human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Exp Hematol. 2015;43(10):912–918.e912. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mosca M, Hermange G, Tisserand A, et al. Inferring the dynamics of mutated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells induced by IFNα in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2021;138(22):2231–2243. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021010986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao TN, Hansen N, Stetka J, et al. JAK2-V617F and interferon-α induce megakaryocyte-biased stem cells characterized by decreased long-term functionality. Blood. 2021;137(16):2139–2151. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020005563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Austin RJ, Straube J, Bruedigam C, et al. Distinct effects of ruxolitinib and interferon-alpha on murine JAK2V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm hematopoietic stem cell populations. Leukemia. 2020;34(4):1075–1089. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0638-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knudsen TA, Skov V, Stevenson K, et al. Genomic profiling of a randomized trial of interferon-α vs hydroxyurea in MPN reveals mutation-specific responses. Blood Adv. 2022;6(7):2107–2119. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Czech J, Cordua S, Weinbergerova B, et al. JAK2V617F but not CALR mutations confer increased molecular responses to interferon-α via JAK1/STAT1 activation. Leukemia. 2019;33(4):995–1010. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mascarenhas J, Kosiorek HE, Prchal JT, et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of interferon-α vs hydroxyurea in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2022;139(19):2931–2941. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021012743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gisslinger H, Klade C, Georgiev P, et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus standard therapy for polycythaemia vera (PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV): a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial and its extension study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(3):e196–e208. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiladjian JJ, Klade C, Georgiev P, et al. Long-term outcomes of polycythemia vera patients treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b. Leukemia. 2022;36(5):1408–1411. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01528-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stadler M, Chelbi-Alix MK, Koken MH, et al. Transcriptional induction of the PML growth suppressor gene by interferons is mediated through an ISRE and a GAS element. Oncogene. 1995;11(12):2565–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dagher T, Maslah N, Edmond V, et al. JAK2V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm eradication by a novel interferon/arsenic therapy involves PML. J Exp Med. 2021;218(2) doi: 10.1084/jem.20201268. e20201268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saleiro D, Wen JQ, Kosciuczuk EM, et al. Discovery of a signaling feedback circuit that defines interferon responses in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1750. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29381-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sørensen AL, Mikkelsen SU, Knudsen TA, et al. Ruxolitinib and interferon-α2 combination therapy for patients with polycythemia vera or myelofibrosis: a phase II study. Haematologica. 2020;105(9):2262–2272. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.235648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bandaranayake RM, Ungureanu D, Shan Y, Shaw DE, Silvennoinen O, Hubbard SR. Crystal structures of the JAK2 pseudokinase domain and the pathogenic mutant V617F. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(8):754–759. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glassman CR, Tsutsumi N, Saxton RA, Lupardus PJ, Jude KM, Garcia KC. Structure of a Janus kinase cytokine receptor complex reveals the basis for dimeric activation. Science. 2022;376(6589):163–169. doi: 10.1126/science.abn8933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harrison C, Kiladjian JJ, Al-Ali HK, et al. JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):787–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vannucchi AM, Kiladjian JJ, Griesshammer M, et al. Ruxolitinib versus standard therapy for the treatment of polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):426–435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou T, Georgeon S, Moser R, Moore DJ, Caflisch A, Hantschel O. Specificity and mechanism-of-action of the JAK2 tyrosine kinase inhibitors ruxolitinib and SAR302503 (TG101348) Leukemia. 2014;28(2):404–407. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R, Talpaz M, et al. Pacritinib vs best available therapy, including ruxolitinib, in patients with myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):652–659. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singer JW, Al-Fayoumi S, Ma H, Komrokji RS, Mesa R, Verstovsek S. Comprehensive kinase profile of pacritinib, a nonmyelosuppressive Janus kinase 2 inhibitor. J Exp Pharmacol. 2016;8:11–19. doi: 10.2147/JEP.S110702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gerds AT, Savona MR, Scott BL, et al. Determining the recommended dose of pacritinib: results from the PAC203 dose-finding trial in advanced myelofibrosis. Blood Adv. 2020;4(22):5825–5835. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mesa RA, Vannucchi AM, Mead A, et al. Pacritinib versus best available therapy for the treatment of myelofibrosis irrespective of baseline cytopenias (PERSIST-1): an international, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(5):e225–e236. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30027-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ganz T. Anemia of inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1148–1157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1804281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oh ST, Talpaz M, Gerds AT, et al. ACVR1/JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor momelotinib reverses transfusion dependency and suppresses hepcidin in myelofibrosis phase 2 trial. Blood Adv. 2020;4(18):4282–4291. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mesa RA, Kiladjian J-J, Catalano JV, et al. SIMPLIFY-1: a phase III randomized trial of momelotinib versus ruxolitinib in Janus kinase inhibitor–naïve patients with myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3844–3850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Version 2, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf

- 69.Mesa RA, Gerds AT, Vannucchi A, et al. MOMENTUM: phase 3 randomized study of momelotinib (MMB) versus danazol (DAN) in symptomatic and anemic myelofibrosis (MF) patients previously treated with a JAK inhibitor. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 16):7002. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pardanani A, Laborde R, Lasho T, et al. Safety and efficacy of CYT387, a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2013;27(6):1322–1327. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guglielmelli P, Rotunno G, Bogani C, et al. Ruxolitinib is an effective treatment for CALR-positive patients with myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2015;173(6):938–940. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koppikar P, Bhagwat N, Kilpivaara O, et al. Heterodimeric JAK-STAT activation as a mechanism of persistence to JAK2 inhibitor therapy. Nature. 2012;489(7414):155–159. doi: 10.1038/nature11303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dunbar A, Bowman RL, Park Y, et al. Jak2V617F reversible activation shows an essential requirement for Jak2V617F in myeloproliferative neoplasms. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.18.492332 Preprint posted online 18 May 2022.

- 74.Chapeau EA, Mandon E, Gill J, et al. A conditional inducible JAK2V617F transgenic mouse model reveals myeloproliferative disease that is reversible upon switching off transgene expression. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0221635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meyer SC, Keller MD, Chiu S, et al. CHZ868, a type II JAK2 inhibitor, reverses type I JAK inhibitor persistence and demonstrates efficacy in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(1):15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rai S, Stetka J, Usart M, et al. The second generation type II JAK2 inhibitor, AJ1- 10502, demonstrates enhanced selectivity, improved therapeutic efficacy and reduced mutant cell fraction compared to type I JAK2 inhibitors in models of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) [abstract] Blood. 2022;140(suppl 1) Abstract 2992. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang J, Weisberg EL, Liu X, et al. Small molecule inhibition of deubiquitinating enzyme JOSD1 as a novel targeted therapy for leukemias with mutant JAK2. Leukemia. 2022;36(1):210–220. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chang Y, Min J, Jarusiewicz JA, et al. Degradation of Janus kinases in CRLF2-rearranged acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2021;138(23):2313–2326. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pardanani A, Harrison C, Cortes JE, et al. Safety and efficacy of fedratinib in patients with primary or secondary myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(5):643–651. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mascarenhas J, Kosiorek HE, Bhave R, et al. Treatment of myelofibrosis patients with the TGF-β 1/3 inhibitor AVID200 (MPN-RC 118) induces a profound effect on platelet production. Blood. 2021;138:142. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gill H, Yacoub A, Pettit KM, et al. A phase 2 study of the LSD1 inhibitor Img-7289 (bomedemstat) for the treatment of advanced myelofibrosis [abstract] Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1) Abstract 139. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mascarenhas J, Komrokji RS, Palandri F, et al. Randomized, single-blind, multicenter phase II study of two doses of imetelstat in relapsed or refractory myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(26):2881–2892. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vachani P, Lange A, Delgado RG, et al. Potential disease-modifying activity of navtemadlin (KRT-232), a first-in-class MDM2 inhibitor, correlates with clinical benefits in relapsed/refractory myelofibrosis (MF) [abstract] Blood. 2021;138 Abstract 3581. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Harrison CN, Garcia JS, Somervaille TCP, et al. Addition of navitoclax to ongoing ruxolitinib therapy for patients with myelofibrosis with progression or suboptimal response: phase II safety and efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(15):1671–1680. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yacoub A, Wang ES, Rampal RK, et al. Abstract CT162: Addition of parsaclisib (INCB050465), a PI3Kδ inhibitor, in patients with suboptimal response to ruxolitinib: A phase 2 study in patients with myelofibrosis. Clin Trials. 2021;81(suppl 13):CT162. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kremyanskaya M, Mascarenhas J, Palandri F, et al. Pelabresib (CPI-0610) monotherapy in patients with myelofibrosis-update of clinical and translational data from the ongoing manifest trial [abstract] Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1) Abstract 141. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mascarenhas J, Kremyanskaya M, Patriarca A, et al. S198: BET inhibitor pelabresib (CPI-0610) combined with ruxolitinib in patients with myelofibrosis—JAK inhibitor-naïve or with suboptimal response to ruxolitinib—preliminary data from the manifest study. HemaSphere. 2022;6:99–100. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tantravahi SK, Kim SJ, Sundar D, et al. A phase 2 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of selinexor in patients with myelofibrosis refractory or intolerant to JAK inhibitors [abstract] Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1) Abstract 143. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yacoub A, Patnaik MM, Ali H, et al. A phase 1/2 study of single agent tagraxofusp, a firstin- class CD123-targeted therapy, in patients with myelofibrosis that is relapsed/refractory following JAK inhibitor therapy [abstract] Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1) Abstract 140. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hoffman R, Ginzburg Y, Kremyanskaya M, et al. Rusfertide (PTG-300) treatment in phlebotomy-dependent polycythemia vera patients. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 16):7003. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ginzburg Y, Kirubamoorthy K, Salleh S, et al. Rusfertide (PTG-300) induction therapy rapidly achieves hematocrit control in polycythemia vera patients without the need for therapeutic phlebotomy [abstract] Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1) Abstract 90. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Palandri F, Ross D, Cochrane T, et al. P1033: a phase 2 study of the LSD1 inhibitor IMG-7289 (bomedemstat) for the treatment of essential thrombocythemia (ET) HemaSphere. 2022;6:923–924. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bogani C, Bartalucci N, Martinelli S, et al. mTOR inhibitors alone and in combination with JAK2 inhibitors effectively inhibit cells of myeloproliferative neoplasms. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stivala S, Codilupi T, Brkic S, et al. Targeting compensatory MEK/ERK activation increases JAK inhibitor efficacy in myeloproliferative neoplasms. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(4):1596–1611. doi: 10.1172/JCI98785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brkic S, Stivala S, Santopolo A, et al. Dual targeting of JAK2 and ERK interferes with the myeloproliferative neoplasm clone and enhances therapeutic efficacy. Leukemia. 2021;35(10):2875–2884. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01391-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Leverson JD, Phillips DC, Mitten MJ, et al. Exploiting selective BCL-2 family inhibitors to dissect cell survival dependencies and define improved strategies for cancer therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(279):279ra240. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Winter PS, Sarosiek KA, Lin KH, et al. RAS signaling promotes resistance to JAK inhibitors by suppressing BAD-mediated apoptosis. Sci Signal. 2014;7(357):ra122. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Waibel M, Solomon VS, Knight DA, et al. Combined targeting of JAK2 and Bcl-2/Bcl-xL to cure mutant JAK2-driven malignancies and overcome acquired resistance to JAK2 inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2013;5(4):1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guo J, Roberts L, Chen Z, Merta PJ, Glaser KB, Shah OJ. JAK2V617F drives Mcl-1 expression and sensitizes hematologic cell lines to dual inhibition of JAK2 and Bcl-xL. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0114363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pemmaraju N, Garcia JS, Potluri J, et al. Addition of navitoclax to ongoing ruxolitinib treatment in patients with myelofibrosis (REFINE): a post-hoc analysis of molecular biomarkers in a phase 2 study. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(6):e434–e444. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tefferi A, Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, et al. MIPSS70+ version 2.0: Mutation and Karyotype-Enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System for primary myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1769–1770. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Patel KP, Newberry KJ, Luthra R, et al. Correlation of mutation profile and response in patients with myelofibrosis treated with ruxolitinib. Blood. 2015;126(6):790–797. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-633404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Spiegel JY, McNamara C, Kennedy JA, et al. Impact of genomic alterations on outcomes in myelofibrosis patients undergoing JAK1/2 inhibitor therapy. Blood Adv. 2017;1(20):1729–1738. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017009530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kleppe M, Koche R, Zou L, et al. Dual targeting of oncogenic activation and inflammatory signaling increases therapeutic efficacy in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(1):29–43.e27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sashida G, Wang C, Tomioka T, et al. The loss of Ezh2 drives the pathogenesis of myelofibrosis and sensitizes tumor-initiating cells to bromodomain inhibition. J Exp Med. 2016;213(8):1459–1477. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yang H, Kurtenbach S, Guo Y, et al. Gain of function of ASXL1 truncating protein in the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2018;131(3):328–341. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-789669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Whyte WA, Bilodeau S, Orlando DA, et al. Enhancer decommissioning by LSD1 during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2012;482(7384):221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lara-Astiaso D, Weiner A, Lorenzo-Vivas E, et al. Immunogenetics. chromatin state dynamics during blood formation. Science. 2014;345(6199):943–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1256271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sprüssel A, Schulte JH, Weber S, et al. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 restricts hematopoietic progenitor proliferation and is essential for terminal differentiation. Leukemia. 2012;26(9):2039–2051. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Niebel D, Kirfel J, Janzen V, Höller T, Majores M, Gütgemann I. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) in hematopoietic and lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2014;124(1):151–152. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-569525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jutzi JS, Kleppe M, Dias J, et al. LSD1 inhibition prolongs survival in mouse models of MPN by selectively targeting the disease clone. Hemasphere. 2018;2(3):e54. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Palandri F, Vianelli N, Ross DM, et al. A phase 2 study of the LSD1 inhibitor Img- 7289 (bomedemstat) for the treatment of essential thrombocythemia (ET) [abstract] Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1) Abstract 386. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cusan M, Cai SF, Mohammad HP, et al. LSD1 inhibition exerts its antileukemic effect by recommissioning PU.1- and C/EBPα-dependent enhancers in AML. Blood. 2018;131(15):1730–1742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-807024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Maiques-Diaz A, Spencer GJ, Lynch JT, et al. Enhancer activation by pharmacologic displacement of LSD1 from GFI1 induces differentiation in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Rep. 2018;22(13):3641–3659. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vinyard ME, Su C, Siegenfeld AP, et al. CRISPR-suppressor scanning reveals a nonenzymatic role of LSD1 in AML. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15(5):529–539. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0263-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303(5659):844–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Iancu-Rubin C, Mosoyan G, Parker CC, Eng K, Hoffman R. Imetelstat (GRN163L), a telomerase inhibitor selectively affects malignant megakaryopoiesis in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) [abstract] Blood. 2014;124(21) Abstract 4582. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Uras IZ, Maurer B, Nivarthi H, et al. CDK6 coordinates JAK2 (V617F) mutant MPN via NF-κB and apoptotic networks. Blood. 2019;133(15):1677–1690. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-08-872648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dutta A, Nath D, Yang Y, Le BT, Mohi G. CDK6 is a therapeutic target in myelofibrosis. Cancer Res. 2021;81(16):4332–4345. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-0590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rampal RK, Pinzon-Ortiz M, Somasundara AVH, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of combined JAK1/2, Pan-PIM, and CDK4/6 inhibition in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(12):3456–3468. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ginzburg YZ, Feola M, Zimran E, Varkonyi J, Ganz T, Hoffman R. Dysregulated iron metabolism in polycythemia vera: etiology and consequences. Leukemia. 2018;32(10):2105–2116. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0207-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Casu C, Oikonomidou PR, Chen H, et al. Minihepcidin peptides as disease modifiers in mice affected by β-thalassemia and polycythemia vera. Blood. 2016;128(2):265–276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-10-676742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Klampfl T, Gisslinger H, Harutyunyan AS, et al. Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2379–2390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.How J, Hobbs GS, Mullally A. Mutant calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2019;134(25):2242–2248. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Elf S, Abdelfattah NS, Chen E, et al. Mutant calreticulin requires both its mutant C-terminus and the thrombopoietin receptor for oncogenic transformation. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(4):368–381. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Araki M, Yang Y, Masubuchi N, et al. Activation of the thrombopoietin receptor by mutant calreticulin in CALR-mutant myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(10):1307–1316. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-671172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chachoua I, Pecquet C, El-Khoury M, et al. Thrombopoietin receptor activation by myeloproliferative neoplasm associated calreticulin mutants. Blood. 2016;127(10):1325–1335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-681932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Araki M, Yang Y, Imai M, et al. Homomultimerization of mutant calreticulin is a prerequisite for MPL binding and activation. Leukemia. 2019;33(1):122–131. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Rivera JF, Baral AJ, Nadat F, et al. Zinc-dependent multimerization of mutant calreticulin is required for MPL binding and MPN pathogenesis. Blood Adv. 2021;5(7):1922–1932. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Elf S, Abdelfattah NS, Baral AJ, et al. Defining the requirements for the pathogenic interaction between mutant calreticulin and MPL in MPN. Blood. 2018;131(7):782–786. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-08-800896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pecquet C, Chachoua I, Roy A, et al. Calreticulin mutants as oncogenic rogue chaperones for TpoR and traffic-defective pathogenic TpoR mutants. Blood. 2019;133(25):2669–2681. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-09-874578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jutzi JS, Marneth AE, Ciboddo M, et al. Whole-genome CRISPR screening identifies N-glycosylation as a genetic and therapeutic vulnerability in CALR-mutant MPN. Blood. 2022;140(11):1291–1304. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Pronier E, Cifani P, Merlinsky TR, et al. Targeting the CALR interactome in myeloproliferative neoplasms. JCI Insight. 2018;3(22) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.122703. e122703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ibarra J, Elbanna YA, Kurylowicz K, et al. Type I but not type II calreticulin mutations activate the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway of the unfolded protein response to drive myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022;3(4):298–315. doi: 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-21-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Jutzi JS, Marneth AE, Jiménez-Santos MJ, et al. CALR-mutated cells are vulnerable to combined inhibition of the proteasome and the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Leukemia. 2023;37(2):359–369. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01781-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tvorogov D, Thompson-Peach CAL, Foßelteder J, et al. Targeting human CALR-mutated MPN progenitors with a neoepitope-directed monoclonal antibody. EMBO Rep. 2022;23(4):e52904. doi: 10.15252/embr.202152904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Achyutuni S, Nivarthi H, Majoros A, et al. Hematopoietic expression of a chimeric murine-human CALR oncoprotein allows the assessment of anti-CALR antibody immunotherapies in vivo. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(6):698–707. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kihara Y, Araki M, Imai M, et al. Therapeutic potential of an antibody targeting the cleaved form of mutant calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms [abstract] Blood. 2020;36(suppl 1) Abstract 716. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Reis E, Buonpane R, Celik H, et al. Discovery of INCA033989, a monoclonal antibody that selectively antagonizes mutant calreticulin oncogenic function in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) [abstract] Blood. 2022;140(suppl 1) Abstract 6. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Gigoux M, Holmström MO, Zappasodi R, et al. Calreticulin mutant myeloproliferative neoplasms induce MHC-I skewing, which can be overcome by an optimized peptide cancer vaccine. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(649):eaba4380. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aba4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Holmström MO, Ahmad SM, Klausen U, et al. High frequencies of circulating memory T cells specific for calreticulin exon 9 mutations in healthy individuals. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9(2):8. doi: 10.1038/s41408-018-0166-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Cimen Bozkus C, Roudko V, Finnigan JP, et al. Immune checkpoint blockade enhances shared neoantigen-induced T-cell immunity directed against mutated calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(9):1192–1207. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]