Abstract

Objective

To explore graduate-entry medical students’ experiences of racial microaggressions, the impact of these on learning, performance and attainment, and their views on how these can be reduced.

Design

Qualitative study using semistructured focus groups and group interviews.

Setting

UK.

Participants

20 graduate-entry medical students were recruited using volunteer and snowball sampling; all students self-identified as being from racially minoritised (RM) backgrounds.

Results

Participants reported experiencing numerous types of racial microaggressions during their time at medical school. Students’ accounts highlighted how these impacted directly and indirectly on their learning, performance and well-being. Students frequently reported feeling uncomfortable and out of place in teaching sessions and clinical placements. Students also reported feeling invisible and ignored in placements and not being offered the same learning opportunities as their white counterparts. This led to lack of access to learning experiences or disengagement from learning. Many participants described how being from an RM background was associated with feelings of apprehension and having their ‘guards up’, particularly at the start of new clinical placements. This was perceived to be an additional burden that was not experienced by their white counterparts. Students suggested that future interventions should focus on institutional changes to diversify student and staff populations; shifting the culture to build and maintain inclusive environments; encouraging open, transparent conversations around racism and promptly managing any student-reported racial experiences.

Conclusion

RM students in this study reported that their medical school experiences were regularly affected by racial microaggressions. Students believed these microaggressions impeded their learning, performance and well-being. It is imperative that institutions increase their awareness of the difficulties faced by RM students and provide appropriate support in challenging times. Fostering inclusion as well as embedding antiracist pedagogy into medical curricula is likely to be beneficial.

Keywords: MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training)

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study uses a social constructivist approach, which provides an understanding of students’ lived experiences of racial microaggressions and their perspectives on the impact of racial microaggressions on their learning, performance and well-being.

This study has a multi-institutional, multigender, multicohort qualitative data set.

The use of online focus groups and group interviews allowed frank responses and recollection was facilitated through discussion.

Data collection was conducted online due to the safety restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially affecting the rapport between the researchers and participants.

Assessing a statistically significant association between racial microaggressions and medical students’ mental health was beyond the scope of this paper.

Introduction

Differential attainment in medical education has been well documented globally.1 Studies suggest that students from racially minoritised (RM) backgrounds, on average, perform less well than white counterparts in both machine-marked assessments of clinical knowledge and practical assessments of clinical competence.2–4 It has been noted that these differential attainments related to RM groups represent complex, systematic inequalities. These include prolonged social, economic and educational inequalities in societies as well as structural and institutional policies and practices that promote white majority cultures that impact negatively on the health and learning experiences of RM students.5–7 In recent years, studies on differential attainment have widened to explore how experiences of racism and discrimination in medical education impact on learners and how these can be addressed at structural and individual levels.

While researching overt and direct forms of racism, such as racial epithets or physical assaults, in medical education continues to be important, it has been recognised that more subtle forms of racism such as racial microaggressions impact on students and are likely to contribute to attainment differentials.8 9 Racial microaggressions are defined as ‘brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioural, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of colour’.10 Racial microaggressions can be difficult to manage due to their intangibility; they are often minimised as simple racial faux pas or cultural missteps.11 Studies have shown that these ‘subtle racist’ interactions12 have caused significant distress, affect physical and mental health and have impacted on learning and academic attainment on learners in different educational settings, including primary, secondary and tertiary educational institutions.13–19 The wider literature on racial microaggressions also suggests that experiencing racial microaggressions in the classroom can contribute towards hostile educational climates and has been linked to feelings of isolation, self-doubt and invisibility.20–22 Moreover, racial microaggressions are also associated with anxiety, depression and alcohol use, and may alter diurnal cortisol secretion leading to increased physiological stress responses.23–25

While evidence of racial microaggressions and their impact on learners in medicine is emerging, the evidence base relating to medical students is small and largely from the USA.9 11 12 26–32 Although these studies document medical students’ reports of microaggressions and provide some evidence of impacts on learning, with the exception of Ackerman-Barger et al’s work,11 they offer few insights into how microaggressions directly and indirectly impact on students’ learning and performance. Furthermore, the extent to which the findings from these studies can be extended to medical students learning in different healthcare systems and sociocultural contexts beyond the USA is unclear. Two recent studies from the UK33 and Sweden12 highlighted daily experiences of microaggressions and provided some limited insights on impacts on learning. If medical schools are to address differential attainment, diversify the medical workforce and create positive learning environments for RM students, there is an urgent need to understand how racial microaggressions are experienced by medical students in other countries and how they impact on their learning.

To the best of our knowledge, no published studies have explored, in any depth, racial microaggressions as experienced by UK medical students and their impact on learning. The UK Equality Act 2010 places a legal duty on universities to address any form of discrimination or harassment related to a protected characteristic that may be adversely impacting on students’ learning experiences and environment.34 Graduate-entry medical (GEM) students have already demonstrated high academic achievements as they enter the medical programme with an existing undergraduate degree. As GEM courses currently account for approximately 10% of all UK medical programmes,35 it is important to report the experiences of RM GEM students and examine any impact on learning and performance; thus, contributing to the portfolio of research into racism and differential attainment in medical education.

We recognise that the use of terms to describe minority communities is a contested issue. It is therefore necessary to clearly establish a shared lexicon between the authors and readers of this paper. ‘Race’ is a socially constructed human categorisation system used to distinguish between groups of individuals that have similar phenotypes.36 Due to the social construction of ‘race’, dominant groups have shared and influenced racial categories in order to uphold power structures, resulting in racial inequality. Despite its social construction, ‘race’ is significant in the daily realities of RM people. We have chosen to use the term RM throughout this paper. Many scholars have highlighted the problematic use of the term ‘Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic’ (BAME), including its grouping together of diverse ethnicities into a single homogenous ethnic group.37 38 The term RM provides a social constructionist approach to understanding that individuals have been actively minoritised by others through social processes of power and privilege.39 Terms such as BAME, ethnic minority and person of colour do not acknowledge the influence of social processes. Although we use the term RM, some participants in this study used other terms such as Black and Minority Ethnic (BME); these are preserved in any quotes used to maintain authenticity. While we support the use of RM, we are aware that language is continuously evolving within and between groups.

This paper reports data from a study of GEM students in the UK that built on Ackerman-Barger et al’s work,11 exploring UK GEM students’ experiences of racial microaggressions and examining the impacts of these on learning and performance. The study had three aims: to identify experiences of racial microaggressions among RM medical students; to explore student perspectives on how their experiences of microaggressions impacted on their learning and performance; and to use the lens of the student participants to identify how medical schools can reduce racial microaggressions and build more inclusive learning environments.

Methods

Design

To explore and understand medical school students’ experiences, this work was undertaken through a social constructivist lens. Social constructivism emphasises that learning and other cognitive functions are critically influenced by the environment, culture and social interactions.40 Given that students’ learning experience in medical education can be theorised as a social process,40 social constructivism is an appropriate conceptual framework to direct and guide this work. A qualitative approach using focus groups and group interviews to collect participants’ narratives was selected, as this enabled reporting of the realities as perceived by participants.41–43

Befitting our interpretivist approach, we also acknowledge the active role of the researchers (and subsequent subjectivity) in this study’s design and analysis.44 Our research process was shaped by our team’s diverse backgrounds, perspectives and personal experiences of racial microaggressions; all of which enabled us to challenge ourselves and each other regarding how our subjectivity shaped our inquiry and interpretation. Thus, in the interest of reflexivity, we have detailed our own backgrounds. NM is an honorary clinical research fellow and an MSc student in medical education currently researching differential attainment, and a medical doctor who has experienced racial microaggressions first-hand. TZ and GW are GEM students, who have witnessed and experienced racism during their studies. OS is a professor of medical education and a consultant obstetrician and urogynaecologist with expertise in exploring differential attainment and has also experienced racial microaggressions. NM, TZ, GW and OS identify as being from RM backgrounds, namely Black British, Asian Pakistani, Mixed White/Black Caribbean and Black African, respectively. CB is an associate professor in health sciences who has extensively researched health and medical education in relation to socioeconomic inequalities and sociodemographic factors. CB previously worked as a nurse, identifies as White British and has witnessed racial microaggressions. All research team members have had prior experience undertaking qualitative research projects. The impact of our individual subjectivities was discussed in team meetings and highlighted and challenged through the various stages of project design, development of data collection tools, data collection and analysis and production of the manuscript. We detail how these our subjectivities had the potential to impact positively and negatively in the Discussion section.

Sample strategy and recruitment

GEM students from medical schools in the UK who self-identified as being from an RM background were recruited. Participants were eligible to participate if they had at least one academic year experience of a UK GEM degree course. Snowball sampling was used in this research to gain access to the smaller RM populations, which can be difficult for researchers to reach. Twenty-one students registered interest and accepted the invitation to participate.

Data collection methods

Data were gathered in focus groups and group interviews using a semistructured interview schedule. Based on participants’ availability, six focus groups, each of four to five multicohort students, were then scheduled throughout June to September 2021. Owing to unexpected scheduling changes, one volunteer could not attend any of the focus groups and as such those scheduled focus groups were more accurately classified as group interviews as they consisted of two to three people. The interview schedule (see online supplemental information) was developed after a review of the literature and drew on themes identified in previous relevant research.11 27 33 The interview schedule consisted of open-ended discussion questions. Participants were asked to identify their experiences of racial microaggressions, and then they were invited to discuss how their experiences impacted them, including their learning and performance. Participants were also invited to identify how medical schools can tackle racial microaggressions and build more inclusive learning environments.

bmjopen-2022-069009supp001.pdf (61.1KB, pdf)

All interviews were held via Microsoft Teams to accommodate the COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions and facilitated by either TZ or GW. Focus groups averaged 60 min and group interviews averaged 45 min. First-hand narratives were encouraged throughout each discussion, and participants were prompted to clarify and expand their answers. Participants were asked to self-report the RM group they identified with using the 2011 UK census categories.45 First-hand narratives were encouraged throughout each discussion, and participants were prompted to clarify and expand their answers. Participants were encouraged to respond to others’ contributions and, if possible, provide similar or contrasting accounts.

Data processing and analysis

All the interviews were video recorded and transcribed verbatim by two researchers (TZ, GW). Transcripts were anonymised and QSR NVivo (Release 1.6.2)46 software was used for data categorisation and management.

Thematic analysis was adopted using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework.41 Themes were generated for each of the three broad interview discussion topics: experiences of racial microaggressions, impact of these experiences on participants and participants’ views on how medical schools can address racial microaggressions. All members of the research team read the transcripts individually to familiarise themselves with the data. Research team members (NM, CB, OS) independently analysed and coded the data, then compared, discussed and collectively agreed on themes. Discussions provided a form of analyst triangulation47 and enabled data interpretation from a range of multicultural interprofessional perspectives,48 establishing the validity and trustworthiness of the data. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines were adopted.49

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design and conduct of this study.

Results

Participants

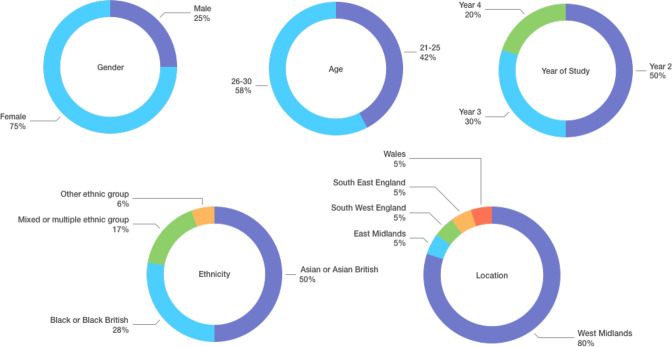

Twenty medical students participated in the study. Participant demographics are shown in figure 1. Participants were registered on a GEM degree course and therefore held either a minimum of an upper second-class honours undergraduate degree (or overseas equivalent) or a postgraduate degree such as a master’s or doctoral qualification. Nineteen out of 20 participants were UK home students, schooled in the UK.

Figure 1.

Participants’ demographics.

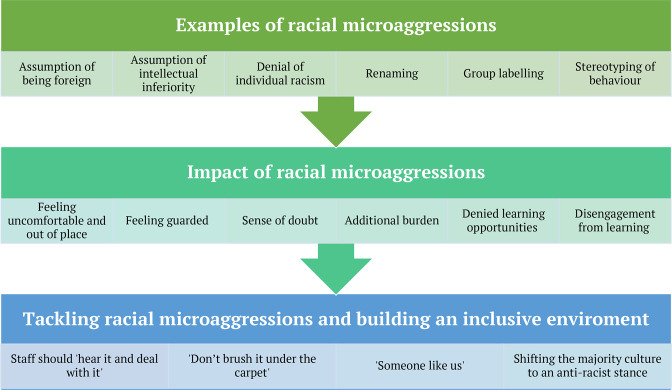

Data were categorised into three main domains: examples of racial microaggressions; impact of racial microaggressions; and participants’ views on tackling racial microaggressions and building an inclusive medical school environment (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Domains and themes.

Experiences of racial microaggressions

All participants highlighted experiences of racial microaggressions during undergraduate medical training. Participants reported that racial microaggressions came from numerous sources, including peers, faculty and patients, and occurred in both classroom and clinical environments. The data were categorised into six themes: assumption of being foreign; assumption of intellectual inferiority; denial of individual racism; renaming; group labelling; and stereotyping of behaviour.

Assumption of being foreign

Most participants described instances of where they were assumed to have been born in a country abroad, even though the UK was their birthplace. Participants reported that such instances frequently occurred in the clinical environment when interacting with clinicians and patients:

I went to see a patient…and then she was just like, ‘Oh where are you from?’ and I was just like ‘London.’ And she was like ‘No.’ (P5; Black British female)

… in terms of consultants, it’s been more of that again, ‘where are you from?’ (P4; Asian British female)

Some also remarked that they would be repeatedly asked the same question related to their heritage if they initially did not provide the response the questioner wanted:

I feel like that happens so much to me … they kind of don’t accept your first answer [when] you say you’re from somewhere in England, they’re like ‘no, no where are you from from?’ (P17; Asian British female)

Some students were also reported that assumptions were made about their English language proficiency. These usually occurred in the clinical environment, with some students describing how it was assumed that English was not their first language, or they had language difficulties. This compounded assumptions that they were foreign born:

And I’ve also been told I speak English really well, uhm, by nursing staff, as well as patients. (P3; Asian British female)

… and they asked if English was my first language and…after saying yes, it is my first language, they kind of started to disagree with me and [asked], ‘are you sure? Are you sure it’s your first language?’ And this was a staff member…a clinical tutor, so that was quite surprising. (P14; Asian British female)

Additionally, several students felt a sense of othering as they commented that the repetitive questioning of their nationality/heritage stemmed from the construction of the normative medical student as a White person:

There’s kind of like an assumption that the normal at medical school is white. (P11; Asian British female)

Assumption of intellectual inferiority

Participants frequently described experiences in which peers and patients made assumptions of intellectual inferiority. Many reported that in the clinical environment patients often questioned their medical student status as well as doubted their clinical and procedural skills ability:

So, patients been refusing to be seen by me, questioning my ability to take bloods or cannulate or, uh, do procedural stuff that any other student would undergo. (P6; Asian British male)

I’ve also had some people tell me that I’m a lot cleverer than I look … do you know what I mean there’s just the [racial] undertone of it. (P16; Mixed White/Black female)

This assumption of intellectual inferiority also appeared to manifest in participant accounts that described the false assumption held by some White students, that their counterparts from RM backgrounds were selected into medical school due to implementation of a racial quota system, rather than based on academic achievement:

We were discussing like how you get into Med school and [the student began] rolling their eyes and saying ‘yeah, but all these quotas are letting you know people who shouldn’t be here, just because of positive, uh, discrimination.’ (P11; Asian British female)

Denial of individual racism

Some participants felt that medical school faculty and peers did not appreciate or understand the challenges they faced, as RM students, during medical school. Participants reported examples of where their personal experiences of racism and bias were often denied by others:

I feel like a lot of the times where I’ve tried to raise things, I think because it doesn’t meet enough, it doesn’t meet the threshold to, for someone to say that it was done with intent, to cause harm, people just try to excuse it away as other people being too sensitive. (P11; Asian British female)

… if I were to make a comment … it would be like I’ve got a brown friend that says this and it’s like I’ve got an Indian friend so it just kind of invalidates your opinion because they have a contact who’s of an ethnic minority [background] to kind of supersede your opinion. (P13; Asian British male)

Renaming

Perception of difficult names was another common racial microaggression described by participants. Several students felt a sense of frustration as they commented faculty and clinicians would often avoid saying their name as they perceived students’ names to be difficult to pronounce:

… so my name is actually like at the top of the alphabet. So, I’m always sort of the first person on the roster and, but I end up being on the last person because they can’t be bothered to pronounce it …and then they’re like ‘right, this is a difficult one.’ (P2; Arab female)

…I’ve even had a consultant a couple of weeks ago, naming me and my CP [clinical partner] ‘One’ and ‘Two.’ … I’d never experienced that [before] …we don’t have long names and it would probably be easier to just call us by names. (P4; Asian British female)

One student described how they changed their name to avoid experiencing this racial microaggression and to stop feeling exasperated:

I changed my name specifically because I was frustrated with people pronouncing my name wrong, so I don’t get it a lot anymore with my first name. (P5; Black British female)

Additionally, participants explained that faculty and peers would frequently mispronounce their name, often trying to shorten, substitute or anglicise it without their permission. Many found this alienating and impeding to build relationships with others:

… I’ve had one member of staff suggest a nickname for me, like they’ve shortened my name for me…my name literally has 6 letters, it’s very easy to pronounce. (P3; Asian British female)

Group labelling

Many participants expressed experiences of group labelling, by their peers, based on their perceived racial appearance. These experiences predominantly occurred in the medical school environment. Some students felt devalued and dehumanised by their peers as less effort was made to identify each person individually:

We are somehow known as the ‘Brown Group’ … that’s how we’re referred to and … when someone said it to my face, I was just like ‘What do you mean Brown Group?’ And they’re like ‘yeah, yeah, you know all of you brown people.’ (P4; Asian British female)

I’ve had people refer to [us] as coloured people. (P18; Black British female)

Misidentification in both the medical school and clinical environments was also reported by participants. Most students described experiences in which peers and medical school faculty had difficulty distinguishing between them and other students from similar RM backgrounds, whereas fewer students reported instances of mistaken identity by clinicians while on their clinical placements:

…I walked into a room and was called the name of another Brown girl with curly hair and I addressed it straight up. I was like … ‘I’m not that person. We’re just both mixed race and have curly hair’ …we don’t even look remotely similar. (P1; Mixed White/Black female)

I was standing at the back of the theatre and then [the consultant] turned to me and … asked me to do something and then she only realised when I was like ‘Oh, I, I can’t do that. I’m not like qualified!’ She was like ‘Oh, it’s you, you’re a student. You [and the registrar] look so alike,’ and I was just like but we really don’t. (P5; Black British female)

Stereotyping of behaviour

Many students talked about experiencing stereotypical slurs, where generalised beliefs about the behaviour of those from specific racial or ethnic groups were often vocalised by peers, faculty and clinicians. Some students remarked that incorrect assumptions were made about them. This negatively affected their relationships with peers and staff:

I’ve been called ‘sassy’ quite a bit. I’ve never been called ‘sassy’ so much until I came to this medical school. (P5; Black British female)

… subtle racist comments [were] made during CBL (Case Based Learning) sessions…, for example [questions like], ‘oh, what are you having for lunch today? Is it you know, rice and curry?’ They [would respond] ‘No, actually I’m having pasta.’ (P4; Asian British female)

A few students remarked that patients were also subject to negative stereotyping by faculty members. Such stereotyping reinforced racial bias and led to the further marginalisation of students from similar RM backgrounds:

… one of the lecturers made reference to [a National Health Service Trust] and how a lot of the [Asian] patients suffer from (malingering) Mrs Bibi syndrome. (P6; Asian British male)

Impact of racial microaggressions on academic learning, performance and mental well-being

Participants reported various impacts of the racial microaggressions on their daily lives including their academic learning, performance and mental well-being. These data were categorised into six themes: feeling uncomfortable and out of place; feeling guarded; sense of doubt; additional burden; denied learning opportunities; and disengagement from learning.

Feeling uncomfortable and out of place

Participants reported how experiencing microaggressions could have a significant impact on their identity and belongingness. The racial microaggressions they experienced made them uncomfortable, lonely, isolated and feeling out of place. This was a strong view reported by most participants.

I would say overall just feeling uncomfortable is a very common feeling I do experience when I do get subjected to microaggressions; being very uncomfortable, feeling very embarrassed and then sometimes, especially on like later reflection and it can even you know, grow into anger and disdain and annoyance. (P18; Black British female)

You kind of, are made to feel so disillusioned and out of place on the course. (P10; Mixed White/Black female)

While some students became frustrated and disillusioned, others tried to cope by hiding their personality, trying to fit in and conform:

And it makes you feel that you have to kind of accommodate others more than they can accommodate you… and so you try and conform as much as possible. (P13; Asian British male)

Feeling guarded

Students expressed how previous experiences of microaggressions lead to feeling worried, anxious and apprehensive in new and different environments. This was associated with a sense of being ‘on guard’ strongly noted by most participants which they found exhausting:

I think another thing that I feel personally is I feel quite apprehensive when I’m starting a new placement because I don’t know how people are going to perceive me and how they’re going to treat me. (P3; Asian British female)

Like whenever we start new things, new rotations, you know how we do so much group work. It’s always like oh well, who’s going to be saying something and like you’re just kind of waiting for the problems to arrive so it leaves you feeling really exhausted. (P11; Asian British female)

Students explained that this feeling is even more pronounced in small settings, for example, General Practice (GP) placements and community home visits, making them guarded and unable to relax in the first instance:

…. it’s sort of unfamiliar territory until you get that sense of ease and then you can sort of relax and let your guard down. But up until then, especially on the first meeting, it’s always guards up and OK, I’m going to have to uh sort of see what I’m going to have to uhm, not deal with, but sort of go with? (P4; Asian British female)

We don’t really know what we are walking into and then for a second we’re like what if they’re really angry or really don’t like people from other cultures. It was all fine in the end, but it made us really weary and then it made me realise how dangerous particular community placements can feel… (P11; Asian British female)

Sense of doubt

The impact of racial microaggressions on emotional well-being was evident in participants’ narratives. Many students discussed how they frequently had feelings of self-doubt, unsure if they were overthinking what happened which is then followed by a sense of inadequacy and questioning whether they were good enough. In the following, three participants discussed their shared experiences of self- doubt:

I think you start doubting yourself a little bit, you’re like, am I reading too much into it? Was this actually that bad? …. It’s I guess, it eats at you sometimes, but it’s mostly just the doubt of, am I, am I really suffering from discrimination right now? This is always the question that I try to ask myself because I, I’m not a person who likes confrontation or things like that so. So, I try to avoid it as much as possible. (P15; Arab male)

I don’t think I could have phrased it any better. I think you’re completely right in saying that it eats at you and it just kind of, makes you doubt yourself both as, I don’t know. (P16; Mixed White/Black female)

Yeah, I really agree with what the others have said as well that yeah, you really doubt yourself you overthink it um and it just makes you, it makes me feel quite like, second class. (P17; Asian British male)

Additional burden

Additional burden refers to the extra worry, stress, apprehension and pressure that participants reported experiencing. Collectively, this was strongly perceived by participants to be over and above that experienced by white majority students and associated with experiencing microaggressions and constantly needing to prove themselves. This ultimately led to stress and, feeling exhausted, as reflected in the following:

It is another kind of added layer to the stress that we already have and I think personally for me, I just quite, find it quite exhausting. …yeah but when it happens constantly, it’s like breaking, it’s like trying to hammer through a wall and you just keep doing constantly, constantly, eventually it’s going to break. (P5; Black British female)

It’s just something else for you to worry about experiencing these microaggressions and how people are viewing you differently. It’s just something else to worry about on top of everything else that I’m guessing a lot of people not from ethnic minorities don’t have to worry about. (P1; Mixed White/Black female)

…having that extra pressure on you in a field that’s already quite like high intensity uhm, can be a lot. (P9; Black British female)

Denied learning opportunities

Denied learning opportunities was one of the key ways racial microaggressions appeared to impact students’ learning. Students strongly stated that these active denials of opportunities occurred in various contexts such as not being able to practise clinical skills, no invitations to study groups, no sharing of resources and poor engagement/differential treatment from clinical faculty despite wanting to keenly participate. The outcome of these were poor and negative student learning experiences:

… my White [clinical partner] kind of gets questioned a little bit more. And I know we all hate being questioned by consultants, but I actually do find it useful sometimes so I would like some questions to be directed my way. But it feels like they kind of questioned her more and put her forward to kind of do histories and things before me, even though I am very willing to. (P1; Mixed White/Black female)

I was actually really excited to go in and see a C-section [caesarean section] for the first time…And there was a White girl in the room as well. And the White girl was the same grade as me, same year as me. We knew each other and she was allowed to kind of assist and do like parts of the procedure and when the obstetrician walked in, she kind of just looked at me and she was like ‘who are you?’ And I was like ‘oh I’m the other Med Student.’ She didn’t even dignify me with a verbal response. She kind of just pointed me out the room which was really demeaning. (P8; Asian British female)

Often patients are more agreeable in being seen by them (White students) and having procedures done by them. (P6; Asian British male)

Disengagement from learning

Impact on students’ learning and performance was a key manifestation of racial microaggressions. This was in part a culmination of experiences as discussed in the themes already reported above: lack of and inequitable learning opportunities; additional burdens; and feeling uncomfortable and out of place. However, students further strongly identified disengagement from learning (from not fully applying themselves, reduced attendance and feeling unwanted) a significant contributor to their poor performance. These impacts on students’ engagement with learning resulted from microaggressions experienced from a range of groups including peers, patients, supervisors and healthcare workers:

For me, they, the only thing that it probably makes me feel is that I don’t want to go into placement and I say that …. Because that’s a regular feeling anyway. You just think to yourself ‘I don’t want to have to go through all of this again.’ …. you’re there to learn ultimately, and if you’re going to get this from all sides, that’s not just patients, but you’re gonna get it from healthcare staff as well, it just makes it ‘well what is the point in me being here?’ (P20; Black British male)

I find a lot, when I’m talking to a consultant or another medical staff member, particularly when I’m with my clinical partner, who is White…. Sometimes I just think, Oh well, they’re not interested in me being here, so I won’t listen and I won’t engage, I won’t kind of apply myself as much as I could, so then obviously, I’m taking less from that experience on placement. (P10; Mixed White/Black female)

… that sort of impacted my performance …. the fact that I was less inclined to go into placements. (P18; Black British female)

The impact of microaggressions on academic performance became clearer as students emphasised the reduced access and disruption of learning opportunities coupled with the disengagement from learning leading to their reduced performance.

Participants’ views on tackling racial microaggressions and building an inclusive medical school environment

Participants were asked their views on how racial microaggressions experienced during their undergraduate training could be tackled by their medical schools and on how medical schools could build more inclusive environments. Participants’ views were categorised into four themes: staff should ‘hear it and deal with it’; ‘Don’t brush it under the carpet’; ‘Someone like us’; and shifting the majority culture to an antiracist stance.

Staff should ‘hear it and deal with it’

A high number of participants identified that often, racial microaggressions had been witnessed by medical school staff but not challenged at the point in time they occurred. Participants felt strongly that medical school staff should deal with racial microaggressions ‘in the moment’, as soon as they witnessed them:

… like on medical school sites, like the CBL facilitators, hardly ever step in when there’s uncomfortable moments and say, well, actually we don’t think that should happen or that shouldn’t be said. And often it’s like kind of, if it’s dealt with at all, it’s never in the moment … if they’re teaching a session or leading a session or group work, if a comment is made, and they hear it, they need to deal with it straight away. (P11; Asian British female)

…it’s almost too late then to act in retrospect. And I think they need to put more in place. So it’s. Being proactive rather than just reactive. (P10; Mixed White/Black female)

Training staff to ‘hear it and deal with it’ in the moment was identified as a strategy to help staff respond proactively to these situations:

… but more staff training, so I think we spoke briefly about earlier how the impact when staff don’t act as allies or when staff let comments go unchallenged or stuff. And let, sort of these racist, racist or racial narratives, run through different settings. Things I think, if the staff and particularly clinical staff too have some sort of training about how to be an ally for all different groups of minorities. (P10; Mixed White/Black female)

‘Don’t brush it under the carpet’

Closely associated with the theme above was the strongly held view that people’s experiences of racial microaggressions should not be ‘brushed under the carpet’. Rather, they should be openly acknowledged, and strategies put in place to challenge them:

… it would be nice if they acknowledged the problem as it is or demonstrated some understanding of the challenges that we face. (P6; Asian British male)

… just acknowledging that these are things that happen and not kind of brushing it under the carpet, ‘cause we all know [name of Medical School] has a habit of just hiding their problems. (P8; Asian British female)

Some participants expressed that the responsibility for calling out racial microaggressions should not be left to RM students, who were already trying to navigate these difficult situations in addition to their studies. A medical school ‘where people call out these [racial] microaggressions …would definitely improve our medical school experience’. Suggestions included having an identified person responsible for speaking up about microaggressions was a possible solution, for example, a senior member of the medical school or a ‘speak up’ guardian. The idea of other students and staff being trained to act as allies or active bystanders was evident in participants’ discourses.

‘Someone like us’

As noted earlier, participants frequently identified that as RM students, they felt they were learning to be doctors in a majority white environment and culture. Most participants reported that there was the need for more faculty members and students ‘like us’ from RM backgrounds. Participants reported that, in their experience, very few academic and faculty members were from RM groups. Extending the number of faculty members from RM groups was viewed as central to building an inclusive medical school.

Faculty members from RM backgrounds were identified as people that could understand the challenges that RM students faced. They were also people that participants said they felt more comfortable sharing experiences with or going to for support. The idea of ‘having mentors that have been through similar difficulties and understood what it is like to be a BME student’ was also raised:

… an increased number of medical staff from a minority background would be useful, ‘cause I think at the moment we have like the one who is kind of responsible for like everything and I know it’s, it probably is a lot of pressure on, on his head because now everything that happens with anyone, they, they kind of feel like he’s the only person that they can talk to, so. (P8; Asian British female)

Because I agree like if we had someone to talk to as well but who is like us, like us being like minority. If we had someone to talk to who is similar to us that would just be so much, so much help. (P13; Asian British male)

I think that’s something that would genuinely really be helpful, but in, in also in the, in terms of having mentors that have been through it and understood what it’s like to be a BME student. I, I often find that there are consultants, for example, who are BME who are able to support you and take the time to understand what you need better than some of the staff at the medical school. (P6; Asian British male)

Having more peers from RM groups was also identified as central to building inclusive medical schools. Participants frequently commented that there should be more students ‘like us’ on medical school programmes and it was a commonly held perception that there were proportionally less students from RM backgrounds who were selected via admission processes.

… I think first and foremost what I would say, and it might not be possible, but just a more diverse cohort… (P13; Asian British male)

Several participants also highlighted the value of peer mentorship schemes that provided RM students with peer support networks:

I was just going to say one scheme that I think has really helped, that I think has been set up by students more than anything else, is the BME mentor scheme. (P14; Asian British female)

That was my only outlet, was the BME mentor, and also I applied for I don’t know number 2 with your mentor, I applied for like you know the general mentors I put please, if possible you can they like be BME, and I did, and so my general parents from Med school. Anyway, my parents were BME, they were all Asian, so it kind of helped. (P13; Asian British male)

Shifting the majority culture to an antiracist stance

A common thread in all focus groups and mentioned by a high majority of participants was the need for major institutional change to both the curriculum and the institutional culture to an antiracist stance. Racial microaggressions from other students were commonly reported and participants voiced strongly that ongoing diversity, inclusivity and antiracism education for students was central to tackling microaggressions and building inclusive medical schools. Participants often appreciated the one-off diversity or antiracism sessions provided by their medical schools, but as the quotes below illustrate, they felt that learning opportunities needed to be compulsory and threaded throughout the medical education programme:

… we had a, a talk on melanin medics at the beginning of the year and, and it was just basically they, I think they were talking about microaggressions and stuff like that and how uhm, how common it is and the, the impacts on people of colour. Um and it was just one talk and I feel like if they had maybe a few more throughout the year and if it was kind of more of a widespread thing, I think that could be really beneficial. (P17; Asian British male)

Yeah, I think like just making these things compulsory and not just like didactic lectures like having some sort of back and forth engagement so you know the student on the other side is actually engaging with what’s being taught, and is actually kind of participating in the material, if that makes sense. (P14; Asian British female)

Although an ongoing education programme was seen as important, there was a strongly held view in all the focus groups that tackling racial microaggressions and building a more inclusive medical school required structural changes within medical schools.

Participants in all of the focus groups highlighted that there needed to be a shift in the majority culture so that racial microaggressions or any forms of racism were unacceptable:

… at the bare minimum is to actually have a zero-tolerance policy for students and for staff… (P1; Mixed White/Black female)

So, I think the problem isn’t usually with the medics like themselves, or at least the Med school students overtly. It’s usually either with the faculty or the patients… (P15; Arab male)

Uhm, I think beyond training, uh, a structural thing or an organisation thing that needs to be put on as an actual policy about how to deal with these kinds of situations, because there isn’t one. (P2; Arab female)

As the above illustrates, shifting the majority culture to an antiracist stance was viewed as requiring widespread changes, including the introduction of policies at university and National Health Service Trust levels that held people to account if their behaviour was unacceptable. Additionally, student-friendly complaints policies for reporting racist encounters and creating a culture within which people are able to speak up, feel confident and supported to challenge other people’s views and behaviours were seen as important.

Discussion

This qualitative study of UK GEM students from RM backgrounds has provided a greater understanding of the racial microaggressions experienced by medical students and its impact on learning and academic performance. To date, their lived experiences of racism during medical training have been underexplored, making it difficult to develop interventions. In the UK, 37% of medical students identify as RM50 and 44.3% of doctors identify as RM even though a significant number are international medical graduates.51 This study, to our knowledge, is the first to explore the racial microaggressions experienced by UK GEM students. Participants reported experiencing six types of racial microaggressions during their undergraduate training: assumptions of being foreign, assumptions of intellectual inferiority, denial of racial experiences, renaming, group labelling and stereotyping. While some microaggressions could be experienced in both classroom and clinical environments, others were more commonly experienced in clinical environments and others tended to relate to the classroom/university environment.

Most students reported that regular experiences of racial microaggressions from peers, faculty, clinicians and patients negatively impacted, directly and indirectly, on their learning, academic performance and well-being. Students frequently reported feeling uncomfortable, out of place, guarded and worried in teaching sessions and clinical placements, where there was an assumption that RM students were ‘foreign’, and that whiteness was the norm. This was perceived to be an additional mental burden that they felt was not experienced by their white counterparts. As described in cognitive load theory, this additional mental burden could be conceptualised as an extrinsic cognitive load, which has the potential to interfere with learning.52 Some participants felt invisible and ignored in placements and not being offered the same learning opportunities as their white counterparts. This led to poor access to learning experiences and disengagement from learning.

Additionally, participants suggested that future interventions should focus on institutional changes they felt would promote inclusivity and develop a sense of belonging within medical schools. Proposed interventions included encouraging open conversations around racism to improve understanding of the experiences of RM students; diversification of student and staff populations; additional faculty training; and changes to medical education curricula which should include a programme of antiracism training and critical consciousness education to promote meaningful understandings about diversity, racism and other forms of social inequality.

This study makes a significant contribution to the medical education literature by building on previous research,11 27 29 53 and theorising about the causes of academic underperformance in RM students. Some of the findings from this study align with previous quantitative and qualitative studies of racial microaggressions in medical education. For example, the experiences of racial microaggressions occurred in both the clinical and non-clinical settings.30 These were similar to those reported in other studies, such as querying students’ country of origin,12 mispronouncing names,32 assuming lower level of intellect compared with peers,11 29 mistaken identity,12 29 32 hypervigilance to threats of racism31 and being ignored.12 29 Moreover, the examples of racial microaggressions identified in this study are also akin to those described in the psychology literature.10 54

The wider literature on marginalised groups may aid understanding of the immediate consequences of racial microaggressions.55 Minority stress theory56 57 suggests that marginalised individuals experience high levels of stress because of prejudice and discrimination associated with their stigmatised identity, leading to long-term psychological and physiological outcomes. Sue and Spanierman also use the life-change model of stress to explain how the cumulative effect of experiencing racial microaggressions can negatively impact RM individuals’ psychological and physical health.58

The psychological impact of racial microaggressions has been alluded to in previous literature, for example, having a negative impact on learning,11 29 feelings of isolation, disengagement,59 experiencing an additional burden11 and fewer clinical opportunities.12 However, a key tenet of our study compared with other studies is that its qualitative methodology and recruitment of students from medical schools across the UK generated in-depth accounts from participants that shed light on the pathway from experiences of microaggressions to lower academic performance via damaging impacts on learning. Most other studies have failed to provide such in-depth narratives due to the adoption of survey methods and some are limited due to accounts from students in single medical schools only.

Previous studies in both the general and student populations have found the additional burden of racial microaggressions increases worry and lowers self-esteem60 and can affect mental health and psychological well-being.18 24 61 However, in our study compared with some others, although mental well-being impacts were implied, impacts on mental health were not specifically investigated. Some quantitative medical education studies that have used validated measures of mental health have been able to explore the association between racial microaggressions and depression27 and burnout.29

While most studies make recommendations for reducing microaggressions and racist experiences, medical students’ views on strategies and policies for change are not well documented. Medical students in Ackerman-Barger et al’s US study11 highlighted the importance of promoting diversity and allyship, curriculum reform, open conversations and safe spaces. Our study of UK GEM students identified similar themes but, additionally, highlighted the importance of ‘hear it and deal with it [microaggressions]’ in the moment, at the point that they occur. It also emphasised the need to ‘shift the majority culture’, with institutional change from the top to the bottom of the medical school.

Strengths and weaknesses

The use of online focus groups and group interviews encouraged frank responses and recollection was facilitated through discussion. Participants were able to build on others’ responses, providing further understanding of experiences and perspectives. The multicohort, multi-institutional data set also enabled the data to elicit narrative experiences from GEM students at various stages of undergraduate training.

Although recruitment of this study was targeted nationally, the largest proportion of study participants came from the same geographical region in the UK. This region, however, has the largest number of GEM students in the UK. As a result, the experiences described in this study may best reflect a specific region of the UK and it is not clear whether these findings would be replicated in other institutions. There was a greater predominance of female participants in our research (M:F 1:3), but RM groups were well represented. This may limit result transferability to male medical students; however, we note that intersectionality between multiple identities is likely to impact attainment in medicine.62 Moreover, we did not note any significant differences between the gender and ethnic groups in their reported experiences.

Conducting the focus groups/interviews online may have affected the rapport between the researchers and participants. While this may have also limited interactions between participants, it had the advantage of facilitating discussions between students from different areas of the country, which would have been difficult if face to face. Another limitation is that some participants may have been fearful of expressing certain views or sharing sensitive personal experiences, while others may have dominated interviews and thus some topics may have been less discussed. As focus groups/interviews were made up of participants from different RM groups, when a student did not have anyone else from their own RM group in their focus group/interview, they may have felt less able to participate or express their views. Because the themes that emerged from the data were reliant on the chosen sample, alternative themes may have developed if the study had included more or different participants. Furthermore, participants may have had specific motives for participating, which may have influenced the topics that emerged in the focus groups/interviews.

Using reflexivity, the interviewers’ identity characteristics and their status as fellow medical students may have influenced the participants’ discussion on specific topics. Participants’ perceptions of the interviewers may have made them feel more at ease while discussing personal and sensitive topics. Other participants, on the other hand, may have found it difficult to explore some issues in depth with a fellow student. While such influence cannot be quantified, and no participant expressed discomfort in discussing their experiences due to the interviewers’ traits, it is still a possibility. It is also possible that individual research team members’ experiences of racism in medical education impacted data interpretation; those who experienced racism may have been more likely to give precedence to student accounts of experiences that resembled their own.

As with other qualitative studies, generalisability is an inherent difficulty63 and thus cannot be claimed. The aim of this study was not to provide generalisations, but to provide an exploration of racial microaggressions in medical education, with a view to inform future research and interventions. While it may have resonance for medical students and other healthcare students learning in similar social and cultural contexts,11 64 our study findings are likely to promote reflection by medical school staff, clinicians, students and other stakeholders.

Implications of the study

All medical students need a supportive, inclusive environment to learn and perform successfully. However, this can be difficult for RM students due to several factors. The high prevalence of racial microaggressions is evident. Racial microaggressions were easily recalled by students and they felt that these microaggressions negatively impacted their day-to-day experiences. Students were able to provide a variety of examples, which involved patients, faculty, peers and clinicians. The racial microaggressions experienced were not isolated occurrences but, instead, regularly occurred throughout students’ undergraduate medical school journey. This repetitive nature could explain the additional mental burden students described, impeding both their well-being and ability to learn and perform well. Our work adds weight to the cognitive load theory, highlighted by Ackerman-Barger and Jacobs,65 where the cognitive impact associated with microaggressions cumulatively builds up over time and impairs productivity, mental function and relationships, impacting on RM students’ learning, performance and progression.

Our findings suggest that more needs to be done to support RM students and increase faculty’s awareness of the difficulties they face. Both tailored student support for marginalised students and environments that foster inclusion have been identified as potential factors to facilitate academic success.66 67 Moreover, diversifying faculty is likely to assist with student support, develop a more inclusive environment and may help increase awareness of the different forms of racism.

The prevalent belief that faculty had a general lack of awareness of this form of racism does not mean that medical schools were not starting to make progress on tackling racial microaggressions; however, our findings indicate that medical schools need to be more proactive in their antiracist pedagogy and interventions. A lack of a systematic approach and consistent education on racial inequities and the effects of racism in the clinical environment was noted in this study. This suggests a need for strategic change and policy initiatives at all levels, including overarching institutional bodies, education and training councils and medical schools themselves. In the UK, the Medical Schools Council’s Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Alliance was recently formed with the specific aim to provide practical guidance to support medical schools to become fair, diverse and inclusive environments in which to study and work.68 We believe that an iterative component of the medical curriculum, specifically focused on equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) issues, should be developed, thus ensuring a number of key EDI topics are regularly revisited throughout the course so that students develop a critical consciousness69 about diversity issues and racism. Moreover, guidance on how to deal with racial microaggressions in all learning environments as well as effective response strategies needs to be developed to empower both recipients and bystanders. Furthermore, this and other studies suggest that medical schools should also review their antiracism training for faculty.

A lack of institutional accountability and policy enforcement by faculty was highlighted in this study and could dissuade students from reporting incidents and seeking support, therefore affecting their well-being and student experience. Our findings suggest that, in addition to training faculty and students, institutions should be dealing with student-reported experiences of racial microaggressions in a timely manner. This will likely restore students’ trust in institutions, increase transparency and contribute towards creating equitable, inclusive learning environments for all students to thrive in. In the UK, small steps have been taken to address institutional accountability, for example, the introduction of British Medical Association Racial Harassment Charter70 and Advance HE Race Equality Charter.71

While this study’s participants attributed several mental health outcomes to experiencing racial microaggressions, none identified any physical health outcomes. Nonetheless, previous studies have highlighted the correlation between racial microaggressions and the activation of physiological stress responses, including the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic–adrenal–medullary (SAM) axis,72–75 suggesting that acute and chronic activations of the HPA and SAM axes could lead to several deleterious health outcomes.23 75 76

Future research

This study highlights a gap in the medical education research literature related to understanding the impact of racism on students’ educational experience, learning and academic performance. Further research is needed to critically examine models and interventions tackling racial microaggressions as well as exploration of institutional efforts to build inclusive learning environments within medical education. Exploration of other types of microaggressions based on protected characteristics, such as religion, sex, sexual orientation, and disability, and their impact on medical students’ mental health, learning, academic performance and retention, would make worthy contributions to the field. This could be explored further by examining the impact of microaggressions and discrimination based on intersecting social identities, for example, Black and female. Research into students and doctors’ experiences of inclusion as well as institutional processes for promoting equity, diversity and belonging needs to be carried out.

Although we have reported RM students as a collective group, we recognise that individuals are not homogenous. Experiences of racial microaggressions may vary between and within RM groups and further research is needed to identify how medical students from different RM groups experience, and are impacted by, racial microaggressions.

Conclusion

This is the first study exploring UK GEM students’ experiences of racial microaggressions. It extends current knowledge of medical students’ experiences of microaggressions and their impact on students’ attainment, highlighting how these impacts are evident in an education and healthcare system beyond the USA. In this study, students from RM backgrounds reported recurrent experiences of racial microaggressions that impeded their learning, academic performance and well-being. Efforts and future interventions focusing on institutional changes to diversify student and staff populations; encouraging open, transparent conversations around racism including racial microaggressions; and promptly managing any student-reported racial experiences are likely to be key to shift the culture to proactively foster inclusive learning environments. As more students from RM backgrounds enter the medical profession, educators should actively aim to remove barriers to learning by supporting students to thrive and reach their full academic potential. Institutions have a responsibility to directly address all forms of racism, including microaggressions. This study highlights salient issues to be considered by all stakeholders of medical education.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Correction notice: The article is updated since it was published, as the author name is updated from Georgia to George.

Contributors: NM conceived the research project. NM designed the research project under the supervision of CB. TZ and GW collected the data. NM, CB and OS analysed the data. All authors interpreted the data. NM, TZ, OS and CB wrote the first draft of the article, and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. NM, CB and OS revised the draft paper. NM is the guarantor of the study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the University of Warwick Biomedical & Scientific Research Ethics Committee (BSREC 17/20-21). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Woolf K. Differential attainment in medical education and training. BMJ 2020;368:m339. 10.1136/bmj.m339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf K, McManus IC, Potts HWW, et al. The mediators of minority ethnic underperformance in final medical school examinations. Br J Educ Psychol 2013;83(Pt 1):135–59. 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02060.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McManus IC, Richards P, Winder BC, et al. Final examination performance of medical students from ethnic minorities. Med Educ 1996;30:195–200. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1996.tb00742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wass V, Roberts C, Hoogenboom R, et al. Effect of ethnicity on performance in a final objective structured clinical examination: qualitative and quantitative study. BMJ 2003;326:800–3. 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fyfe M, Horsburgh J, Blitz J, et al. The do’s, don’ts and do ’'t knows of redressing differential attainment related to race/ethnicity in medical schools. Perspect Med Educ 2022;11:1–14. 10.1007/s40037-021-00696-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 2009;32:20–47. 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health 2019;40:105–25. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neville P. When I say … everyday racism. Medical Education 2022;56:260–1. 10.1111/medu.14667 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/13652923/56/3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullock JL, O’Brien MT, Minhas PK, et al. No one size fits all: a qualitative study of clerkship medical students’ perceptions of ideal supervisor responses to microaggressions. Acad Med 2021;96:S71–80. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol 2007;62:271–86. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackerman-Barger K, Boatright D, Gonzalez-Colaso R, et al. Seeking inclusion excellence: understanding racial microaggressions as experienced by underrepresented medical and nursing students. Acad Med 2020;95:758–63. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kristoffersson E, Rönnqvist H, Andersson J, et al. "it was as if I WA’ n’t there’’ -experiences of everyday racism in a Swedish medical school. Soc Sci Med 2021;270:113678. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith WA, Franklin JD, Hung M. The impact of racial microaggressions across educational attainment for African Americans. Journal of Minority Achievement, Creativity, and Leadership 2020;1:70–93. 10.5325/minoachicrealead.1.1.0070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadal KL, Wong Y, Griffin KE, et al. The adverse impact of racial microaggressions on college students’ self-esteem. Journal of College Student Development 2014;55:461–74. 10.1353/csd.2014.0051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suárez-Orozco C, Casanova S, Martin M, et al. Toxic rain in class: classroom interpersonal microaggressions. Educational Researcher 2015;44:151–60. 10.3102/0013189X15580314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohli R, Solórzano DG. Teachers, please learn our names!: racial microagressions and the K-12 classroom. Race Ethnicity and Education 2012;15:441–62. 10.1080/13613324.2012.674026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harwood SA, Huntt MB, Mendenhall R, et al. Racial microaggressions in the residence halls: experiences of students of color at a predominantly white university. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 2012;5:159–73. 10.1037/a0028956 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huynh VW. Ethnic microaggressions and the depressive and somatic symptoms of Latino and Asian American adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 2012;41:831–46. 10.1007/s10964-012-9756-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sue DW. Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. John Wiley & Sons, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yosso T, Smith W, Ceja M, et al. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate for latina/o undergraduates. Harv Educ Rev 2009;79:659–91. 10.17763/haer.79.4.m6867014157m707l [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solorzano D, Ceja M, Yosso T. n.d. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: the experiences of African American college students. J Negro Educ;2000:60–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torino GC, Rivera DP, Capodilupo CM, et al. Microaggression theory. Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2 October 2018. 10.1002/9781119466642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeiders KH, Landor AM, Flores M, et al. Microaggressions and diurnal cortisol: examining within-person associations among African-American and Latino young adults. J Adolesc Health 2018;63:482–8.:S1054-139X(18)30206-4. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres L, Driscoll MW, Burrow AL. Racial microaggressions and psychological functioning among highly achieving African-Americans: a mixed-methods approach. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 2010;29:1074–99. 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.10.1074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blume AW, Lovato LV, Thyken BN, et al. The relationship of microaggressions with alcohol use and anxiety among ethnic minority college students in a historically white institution. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2012;18:45–54. 10.1037/a0025457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ackerman-Barger K, London M, White D. When an omitted curriculum becomes a hidden curriculum: let’s teach to promote health equity. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2020;31:182–92. 10.1353/hpu.2020.0149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson N, Lett E, Asabor EN, et al. The association of microaggressions with depressive symptoms and institutional satisfaction among a national cohort of medical students. J GEN INTERN MED 2022;37:298–307. 10.1007/s11606-021-06786-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown C, Daniel R, Addo N, et al. The experiences of medical students, residents, fellows, and attendings in the emergency department: implicit bias to microaggressions. AEM Education and Training 2021;5:S49–56. 10.1002/aet2.10670 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/24725390/5/S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chisholm LP, Jackson KR, Davidson HA, et al. Evaluation of racial microaggressions experienced during medical school training and the effect on medical student education and burnout: a validation study. J Natl Med Assoc 2021;113:310–4.:S0027-9684(20)30428-4. 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Espaillat A, Panna DK, Goede DL, et al. An exploratory study on microaggressions in medical school: what are they and why should we care? Perspect Med Educ 2019;8:143–51. 10.1007/s40037-019-0516-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kristoffersson E, Hamberg K. "I have to do twice as well''-managing everyday racism in a Swedish medical school. BMC Med Educ 2022;22:235. 10.1186/s12909-022-03262-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strayhorn TL. Exploring the role of race in black males’ sense of belonging in medical school: a qualitative pilot study. Med Sci Educ 2020;30:1383–7. 10.1007/s40670-020-01103-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrison N, Machado M, Blackburn C. Student perspectives on barriers to performance for black and minority ethnic graduate-entry medical students: a qualitative study in a West Midlands medical school. BMJ Open 2019;9:e032493. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Equality and Human Rights Commission . What equality law means for you as an education provider – further and higher education. Equality and Human Rights Commission; 2014. Available: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/what_equality_law_means_for_you_as_an_education_provide_further_and_higher_education.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumwenda B, Cleland J, Greatrix R, et al. Are efforts to attract graduate applicants to UK medical schools effective in increasing the participation of under-represented socioeconomic groups? a national cohort study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018946. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LeCompte MD, Schensul JJ. Designing and conducting ethnographic research: an introduction: rowman Altamira. 2010.

- 37.Sarfo-Annin JK. Ethnic inclusion in medicine: the ineffectiveness of the "black, Asian and minority ethnic'' metric to measure progress. BJGP Open 2020;4:BJGPO.2020.0155. 10.3399/BJGPO.2020.0155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milner A, Jumbe S. Using the right words to address racial disparities in COVID-19. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e419–20.:S2468-2667(20)30162-6. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30162-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunaratnam Y. n.d. Researching race and ethnicity 6 bonhill Street, London EC2A 4PU. 10.4135/9780857024626 [DOI]

- 40.Kaufman DM. Teaching and learning in medical education: how theory can inform practice. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory, and Practice 2018:37–69. 10.1002/9781119373780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide No. 131. Med Teach 2020;42:846–54. 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, et al. Apa Handbook of research methods in psychology, vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. Washington, 10.1037/13620-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe LV, et al. Shedding the cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ 2017;51:40–50. 10.1111/medu.13124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.UK Government . List of ethnic groups: 2011 census UK: UK government. 2021. Available: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/style-guide/ethnic-groups#2011-census

- 46.QSR International Pty Ltd . NVivo Version Release 1.6.2. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ 2001;322:1115–7. 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) . Table 42-UK domiciled qualifiers by subject of study and ethnicity 2019/20 to 2021/22 He student data UK: higher education statistics agency (HESA). 2023. Available: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/table-42

- 51.UK Government . Nhs workforce UK: UK government. 2020. Available: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/workforce-and-business/workforce-diversity/nhs-workforce/latest

- 52.Young JQ, Van Merrienboer J, Durning S, et al. Cognitive load theory: implications for medical education: AMEE guide No. 86. Med Teach 2014;36:371–84. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.889290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilliam C, Russell CJ. Impact of racial microaggressions in the clinical learning environment and review of best practices to support learners. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2021;51:101090.:S1538-5442(21)00145-0. 10.1016/j.cppeds.2021.101090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams MT, Skinta MD, Martin-Willett R. After pierce and sue: a revised racial microaggressions taxonomy. Perspect Psychol Sci 2021;16:991–1007. 10.1177/1745691621994247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong G, Derthick AO, David EJR, et al. The what, the why, and the how: a review of racial microaggressions research in psychology. Race Soc Probl 2014;6:181–200. 10.1007/s12552-013-9107-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2000;70:42–57. 10.1037/h0087722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–97. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sue DW, Spanierman LB. Microaggressions in everyday life 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2020: 349–xx. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teshome BG, Desai MM, Gross CP, et al. Marginalized identities, mistreatment, discrimination, and burnout among US medical students: cross sectional survey and retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2022;376:e065984. 10.1136/bmj-2021-065984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong-Padoongpatt G, Zane N, Okazaki S, et al. Decreases in implicit self-esteem explain the racial impact of microaggressions among Asian Americans. J Couns Psychol 2017;64:574–83. 10.1037/cou0000217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Teherani A, Hauer KE, Fernandez A, et al. How small differences in assessed clinical performance amplify to large differences in grades and awards: a cascade with serious consequences for students underrepresented in medicine. Acad Med 2018;93:1286–92. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsouroufli M, Rees CE, Monrouxe LV, et al. Gender, identities and intersectionality in medical education research. Med Educ 2011;45:213–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]