Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to explore women’s birthing preferences and the motivational and contextual factors that influence their preferences in Benin City, Nigeria, so as to better understand the low rates of healthcare facility usage during childbirth.

Setting

Two primary care centres, a community health centre and a church within Benin City, Nigeria.

Participants

We conducted one-on-one in-depth interviews with 23 women, and six focus groups (FGDs) with 37 husbands of women who delivered, skilled birth attendants (SBAs), and traditional birth attendants (TBAs) in a semi-rural region of Benin City, Nigeria.

Results

Three themes emerged in the data: (1) women reported frequently experiencing maltreatment from SBAs in clinic settings and hearing stories of maltreatment dissuaded women from giving birth in clinics, (2) women reported that the decision of where to deliver is impacted by how they sort through a range of social, economic, cultural and environmental factors; (3) women and SBAs offered systemic and individual level solutions for increasing usage of healthcare facilities delivery, which included decreasing costs, increasing the ratio of SBAs to patients and SBAs adopting some practices of TBAs, such as providing psychosocial support to women during the perinatal period.

Conclusion

Women in Benin City, Nigeria indicated that they want a birthing experience that is emotionally supportive, results in a healthy baby and is within their cultural scope. Adopting a woman-centred care approach may encourage more women to transition from prenatal care to childbirth with SBAs. Efforts should be placed on training SBAs as well as investigating how non-harmful cultural practices can be integrated into local healthcare systems.

Keywords: Maternal medicine, PUBLIC HEALTH, OBSTETRICS

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

Study findings are consistent with others regarding treatment of women in healthcare facilities in Nigeria.

A multiple disciplinary team of researchers with expertise in qualitative research from Nigeria and the USA were involved in development of the interview and focus group guides and the analysis of the data.

This study also had a few limitations, recall bias by study participants being asked to recall past pregnancy incidents that occurred weeks to years ago.

Cultural bias, the study’s principal investigator is an American born Yoruba Nigerian American.

The study also had a non-representative sample of husbands.

Introduction

Maternal mortality (MM) has decreased by 44% globally between 1990 and 2015, due to infection control, the management of pregnancy related complications such as pre-eclampsia, and blood transfusions.1 However, sub-Saharan African countries maintain the highest MM rates (MMR) worldwide and have experienced the slowest decline.2 The average MMR in sub-Saharan Africa is 547 per 100 000 births, which is more than double the global average of 216 in 100 000 births.3 Within sub-Saharan Africa, disparities in MM also exist. Nigeria maintains the fourth highest MMR in sub-Saharan Africa with a rate of 814 in 100 000 births.3 Currently, Nigeria is second only to India globally for absolute numbers of maternal death, accounting for 14% of the world’s MM.4

The most common obstetric causes of MM in Nigeria are pre-eclampsia, primary postpartum haemorrhage, prolonged obstructed labour, maternal sepsis and antepartum haemorrhage.4 The most common patient-level factors that result in MM are the use of alternative birth attendants (traditional birth attendants (TBAs)), non-use of prenatal care, refusal of recommended treatment and delayed presentation to healthcare facilities.5 Despite research indicating that giving birth in healthcare facilities with skilled birth attendants (SBAs) decrease the likelihood of MM, only 43% of women in Nigeria deliver with an SBA, compared with 58% in sub-Saharan Africa overall and 80% globally.6 7

Interestingly, SBA usage in Nigeria is higher during prenatal care 64%, compared with 43% during childbirth.5 This variance may be due to negative experiences, including dissatisfaction with healthcare facilities and poor attitudes of healthcare providers, as well as lack of transportation, hospital cost, preference for alternative methods such as TBAs, or cultural and/or spiritual reasons.6 8

Unlike SBAs who are accredited healthcare professionals, WHO defines a TBA as ‘a person who assists a mother during childbirth and who initially acquired her skills by delivering babies herself or through apprenticeship to other traditional birth attendants’.9 The perceived benefits of TBA usage is their accessibility, especially in rural areas; affordability, ties to the community and attentiveness to the cultural needs of women during labour.10–12 By contrast, the disadvantage of usage of TBAs is that they lack the training to identify and manage complications such as postpartum haemorrhage or birth asphyxia, resulting in the probability of a delay in care when women need to be transferred to healthcare facilities during obstetric emergencies.13 14

Despite the disadvantages of TBA usage, women throughout sub-Saharan Africa continue to use their services during childbirth for a variety of reasons. Rural women in Ghana reported that poor provider–client interactions and cultural insensitivity in healthcare facilities influenced their use of TBAs over SBAs.10 A study conducted in Tanzania showed that high rates of home births were due to the fact that neither men nor women associated delivering at home with risk of poor outcomes.15 In Malawi, factors that influenced delivery outside of healthcare facilities ranged from rainy season-associated transportation difficulties, unexpectedly quick onset of labour and cultural reasons.16 Studies in Northern Uganda yielded similar results regarding high rates of home birth, including poor client–provider interactions, cost and transportation, which explains the decrease delivery with SBA’s in healthcare facilities compared with degree of usage of SBAs for antenatal care.11

There is little research exploring the childbirth preferences of Nigerian women. However, there are studies indicating a failure of the healthcare system to meet the needs and preferences of women in Nigeria, leading to avoidable MM.17 Adopting a women-centred approach can begin to address the disconnect between the preferences of mothers and services provided by healthcare facilities in Nigeria. To achieve this, a holistic understanding of the preferences of Nigerian women in childbirth must be attained.

We conducted a qualitative study with women in Benin City, Nigeria, to gain a holistic understanding of their preferences regarding childbirth, including issues related to healthcare facility usage. The aim of this study was to explore women’s birthing preferences and the motivational and contextual factors that influence their preferences in Benin City, Nigeria, so as to better understand the low rates of healthcare facility usage during childbirth.

Methods

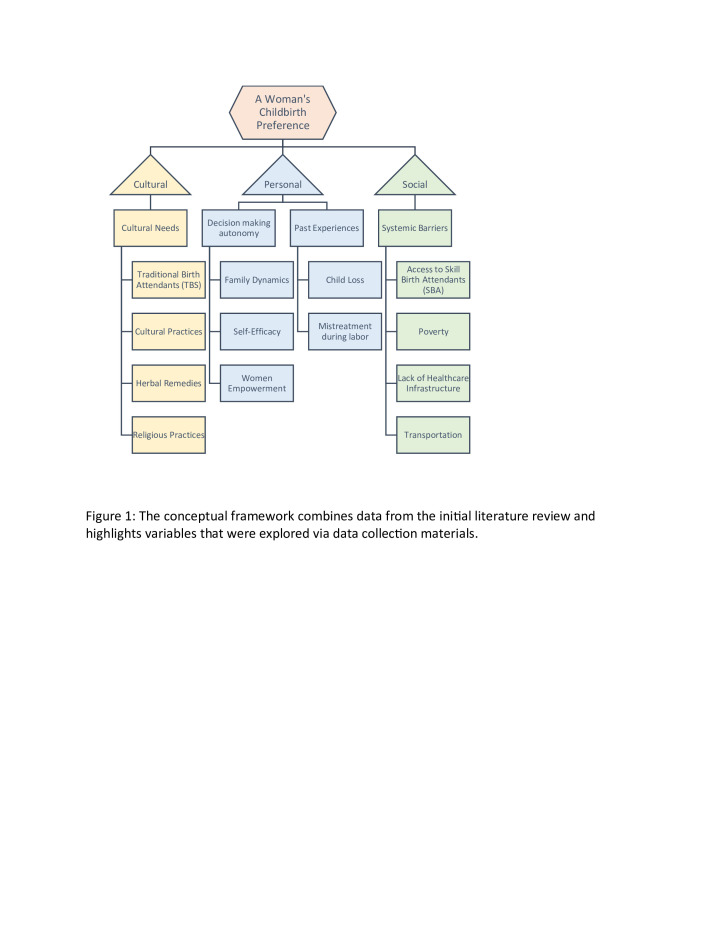

A conceptual framework (figure 1) was developed based on a literature review and used to determine target populations and inform in-depth interview questions and focus group (FG) guides. It also informed data coding and categorisation during analysis. The framework explored how cultural, personal and social factors influence a woman’s childbirth preference.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework combines data from the initial literature review and highlights variables that were explored via data collection materials.

Patient/public involvement

A key stakeholder in the community was actively involved in the creation of the research questions, study design/execution and data analysis. Participants in the study were not involved in setting the research question or study design. Participants were central to recruitment of other participants via snowball sampling.

Sampling and recruitment procedures

We conducted one-on-one in-depth interviews with 23 women, 11 with women who had previously delivered, or planned to deliver outside of healthcare facilities (with a TBA), and 12 with women who had previously delivered or planned to delivery in a healthcare facility with an SBA. Six FGs were conducted. One FGD was conducted with 10 men, three FGDs were conducted with a total of 21 SBAs and two FGDs were conducted with a total of six TBAs in a semi-rural region of Benin City, Nigeria. Participants were chosen using purposive, and snowball sampling and were recruited from the Women’s Health and Action Research Centre, the Centre of Excellence in Reproductive Health Innovation (CERHI), community health centres and churches in Benin City, Nigeria.

Subjects were eligible to participate if they were: (1) pregnant with their first child, (2) women who delivered within healthcare facilities (with an SBAs), (3) women who delivered outside of healthcare facilities (with a TBAs), (4) husbands of women who delivered within or outside of healthcare facilities, (5) SBAs or (6) TBAs, and they had to be between the ages of 18–65, English speaking, and able to provide informed consent.

Participants were prescreened by community health workers from CERHI and introduced to the principal investigator (PI). The PI (DE) rescreened participants, explained the purpose of the study, obtained informed consent and conducted the interviews. Men were recruited from churches, SBAs were recruited from community clinics and TBAs were recruited from the community. FG participants were screened and consented with the same procedure as the interviewees.

Interviews

In-depth interviews were conducted with women who were pregnant with their first child or who had ever delivered in the past. Two different interview guides were used: one for women who delivered within healthcare facilities (with an SBA), and another for women who delivered outside of healthcare facilities (with a TBA). Interview guides for the in-depth interviews were developed using the study’s conceptual framework (figure 1); they explored women’s personal experiences involving childbirth and how that influenced their birthing preferences, and treatment by skilled or traditional labour attendants. The guides also sought to explore the decision-making process of selecting how and where to deliver, and access to healthcare facilities. All participants were asked to give verbal consent to allow for the collection of data and recording of the interview. The interview guides were piloted with three participants, and then revised to ensure that the guide answered the research questions. Additionally, pilot information was used to determine whether questions were easy to understand and appropriate for the target population.

Interviews were conducted in English by the PI. Semi-private locations at the recruitment sites were used to conduct the interviews immediately following screening and consenting.

Focus groups

The categories with which FGs were conducted were SBAs, TBAs and husbands of women who had delivered with or without SBAs. Groups were not mixed to avoid gender and cultural dynamics that may prohibit participants from speaking freely. These FGs contained between 3 and 10 participants each, lasted between 30 min and an hour, and were conducted at a church, clinics or the location where TBAs took deliveries. FGs were conducted in English by the PI. The study’s conceptual framework informed the development of FG guides; an FG guide was developed for each category of participants to explore the sociocultural topics involved with childbirth preferences (figure 1).

Men

One FG was conducted with 14 male participants to explore family dynamics, financial burden of delivery and personal opinions regarding SBAs and TBAs.

Skilled birth attendants

Three FGs were conducted with 17 SBA participants to explore their patient load, perceptions on the treatment of women in labour, why they believe some women prefer TBAs and possible solutions to the low rates of usage of clinics for deliveries.

Traditional birth attendants

Two FGs were conducted with six TBA participants to explore their cultural significance, why they believed women used them, and some of their traditional practices.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the Grounded Theory approach.18 Interviews and FG data were audio recorded and then transcribed. The PI read through the interviews and FG transcripts to identify occurring and reoccurring concepts and patterns within the data. Concepts and patterns were used to develop codes via memoing. A codebook was developed, consisting of 87 codes. Atlas/ti software was employed to assist with data analysis.

Data were coded for recurring themes, significant quotes and information that surprised the PI. Data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection from semi-structured interviews to determine when a saturation of themes had been met. FG data were analysed by the PI after the completion of all FGs. To ensure quality criteria, every fourth transcription and coded document was reviewed by the PI for accuracy of transcription and consistency of coding. To identify quotes of interest and striking passages, memoing was employed. Queries, for example, for ‘TBA’ and ‘comfort’, were applied to further condense data. Condensing of the data and categorisation was applied to further group data and assess recurring themes. Overarching categories were then identified through analysis and grouped into three themes.

Results

Three major themes and 17 subthemes emerged in the data (table 1). The major themes include (1) women experiencing maltreatment from SBAs; (2) factors women reported they consider and (3) solutions presented by participants (table 1). Details of the qualitative information obtained and analysed are presented in online supplemental material.

Table 1.

The study’s findings which include, 3 themes, 17 subthemes and associated evidence

| Themes | Subthemes | Evidence |

| Theme 1: Women reported frequently experiencing maltreatment from SBAs in clinic settings, and hearing stories of maltreatment dissuaded women from giving birth in clinics | Hitting | ‘… by the time you hit that leg, by the time she screams you will see, with that pressure, the baby will come out’ |

| Insults | ‘‘You weren’t complaining when you were having sex, don’t complain now’. They actually told a friend of mine’s wife that, and she actually just started weeping’ | |

| Rumours of neglect and hitting | ‘Most of them here in Benin are not nice, they will even nag you, yell at you. From what I have heard, I haven’t been there’ | |

| Negative prior experience | ‘They did not attend to me well. The injection that they give me swell up, I report to them and they don’t attend to me’ | |

| Theme 2: Women reported that the decision of where to deliver is impacted by how they sort through a range of social, economic, cultural and environmental factors | Healthy baby | ‘Well, you need to endure to get what you want (healthy baby). Normally they shout, they will not regard you as human being, they will treat you without regard. But you need to endure it to get what you want’ |

| Avoid medical intervention | ‘The baby was not ready to come and they cut me, the pain is still there up till now. So that is why I do not go to the clinic. The cut was too much’ | |

| Comfort and encouragement (petting) | ‘I got to the traditional I was given the attention that I needed and the love and warm embrace that I really needed at that time in my life’ | |

| Cultural experience | ‘I think our culture plays a part in it, usually delivery at home with your grandma, your grandniece, with elders in the community or in the neighbourhood, so our culture’ | |

| Spiritual needs | ‘Naturalists believe they want to have their baby within the church premises, where they believe that God is, they have spiritual backup, they have spiritual covering’ | |

| Decision making | ‘Even though the man appears to make the decision, it is informed by the woman’s information’ | |

| Gender of birth attendant | ‘I did not have a preference, I just wanted the baby to come out’ | |

| Cost | ‘I won’t go back to the hospital. The money was too big, if it is native, I will go’ | |

| Unpredictable situations | ‘The nurse that knows me called me and said, madam what are you waiting for. I told her ‘I am in labor and you are asking me this question.’ She then told me that the doctor had left the area. That is now when I went to the native place’ | |

| Theme 3: Women and SBAs offered systemic and individual level solutions for increasing usage of healthcare facilities delivery, which included decreasing costs, increasing the ratio of SBAs to patients and SBAs adopting some practices of TBAs, such as providing psychosocial support to women during the perinatal period | Decrease clinic cost | ‘If the clinic was free I would go, I will go anywhere that is free’ |

| Increase number of SBAs | ‘You may have 5 patients to attend to at the same time, and the facilities do not have the capacity. You may not have the supplies you need, so you are getting frustrated; and your delay causes patients to shout increasing your frustration’ | |

| Retrain SBAs | ‘I think that is what is driving them away, we must also work on our attitude. More empathetic to our clients’ | |

| Adopt non-harmful TBA practices | ‘Because you cannot rule out traditional belief, if it is not harmful, why not. I think we also need to at least study, let’s know these beliefs and add the ones that are not harmful into our own practice’ |

SBA, skilled birth attendant; TBA, traditional birth attendant.

bmjopen-2021-054603supp001.pdf (140.6KB, pdf)

Theme 1: Women reported frequently experiencing maltreatment from SBAs in clinic settings, and hearing stories of maltreatment dissuaded women from giving birth in clinics

Four subthemes ((italicised and bolded) were identified: hitting, verbal insults, rumours of neglect or hitting, and prior negative experiences. Hitting and verbal insults during labour in a clinic setting were reported among women who used SBAs and TBAs for their last child birthing experience and husbands. During FGs, SBAs openly spoke about some of the negative feelings they have towards labouring women, which may inform their maltreatment of these women. During an FG discussion with SBA one reported that:

… by the time you hit that leg, by the time she screams you will see, with that pressure, the baby will come out.

A man recalled some ways that SBAs verbally insult woman:

‘You weren’t complaining when you were having sex, don’t complain now’. They actually told a friend of mine’s wife that, and she actually just started weeping.

Some women who opted to deliver with TBAs reported their birthing choice was influenced by rumours they had heard from other women regarding experiencing insults or hitting during labour by SBAs. A woman who received prenatal care but opted to deliver with a TBA reported:

Most of them here in Benin are not, they will even nag you, yell at you. From what I have heard, I haven’t been there.

Others indicated that their birthing choice was directed by previous negative birthing experiences with SBAs. A woman who delivered her first child with an SBA but opted to use a TBA for her second reported:

From my first experience I do not want to use the clinic anymore.

Theme 2: Women reported that the decision of where to deliver is impacted by how they sort through a range of social, economic, cultural and environmental factors

Below we summarised the seven factors/subthemes which women reported. Most women reported that their birthing preference was largely influenced by what method gave them the best chance to have a healthy baby. Many women were willing to endure mistreatment by SBAs because they trusted that hospitals could provide more specialised care and deal with any birthing complications. A women day two post op from a caesarean section reported:

Well, you need to endure to get what you want (healthy baby). Normally they shout, they will not regard you as human being, they will treat you without regard. But you need to endure it to get what you want.

Willingness to undergo medical interventions such as caesarean sections and episiotomies was something women indicated they considered when deciding to labour with a TBA or an SBA. A woman who delivered her first baby with an SBA and opted to use a TBA for a second delivery reported:

The baby was not ready to come and they cut me, the pain is still there up till now. So that is why I do not go to the clinic. The cut is too much.

Comfort and encouragement during labour was something women, regardless of whether they delivered with TBAs and SBAs, indicated they wanted to receive. Many women who delivered with TBA cited petting (comfort) in labour as a motivating factor. A woman who delivered her child with TBA stated:

I never liked it in the hospital, and when I got to the traditional I was given the attention that I needed and the love and warm embrace that I really needed at that time in my life.

Another factor women considered was the desire for cultural experiences. This included the use of cultural practices and traditional medicine. TBAs reported that women come to them in pursuit of herbal remedies for pregnancy complaints and complications. During FGDs an SBA explained:

I think our culture plays a part in it, usually delivery at home with your grandma, your grandniece, with elders in the community or in the neighborhood, so our culture.

The ability of birth attendants to meet the spiritual needs of women in labour also appeared to influence where they preferred to labour. During an FGD with SBAs some women indicated that they choose to deliver in churches in hope of better birth outcomes:

naturalists believe they want to have their baby within the church premises, where they believe that God is, they have spiritual backup, they have spiritual covering.

Women and men both indicated that the majority of decision-making power regarding where to receive prenatal care and deliver was wielded by women. However, for some women the decision is either shared with their husband or the family matriarch. During FGDs with husbands, one man explained:

she is in charge, she will try to influence, because as a man there is a limit to how much you know.

Some women did state that due to religion or other cultural factors that they preferred female birthing attendants. However, most women reported that modesty or delivering with a male birth attendant did not influence where they chose to labour, they were more occupied with good birthing outcomes:

I did not have a preference, I just wanted the baby to come out.

Clinic cost was a concern for some women and their husbands; and enough to deter them from using SBAs. TBAs and some women on the other hand had a different perspective on the impact of cost, indicating that cost was not a decisive factor. A woman who delivered her previous child with an SBA stated:

Hospital cost is expensive, for the second one I would go to native because in the hospital I delivered vaginally it was almost 50000 naira (about $105.0) that I paid, it’s expensive, so if I deliver again, I will do it at home.

Another factor that women indicated influences their choice to either deliver with a TBA or within healthcare facilities was unpredictable circumstances. This includes rapid or painful labour, transportation, booking issues in the clinic settings, and also unstaffed hospitals. These issues can cause women, even some who planned to deliver in healthcare facilities, to deliver with TBAs as a last resort. These issues speak less to the personal preferences of women but rather systemic infrastructure issues within Nigeria. A woman who planned to deliver with an SBA reported:

The nurse that knows me told me that the doctor had left the area. That is now when I went to the native place.

Theme 3: Women and SBAs offered systemic and individual level solutions for increasing usage of healthcare facilities delivery, which included decreasing costs, increasing the ratio of SBAs to patients and SBAs adopting some practices of TBAs, such as providing psychosocial support to women during the perinatal period

Women reported that a decrease in clinic cost would incentivise the use of healthcare facilities. A woman who delivered with a TBA was asked if she would be more inclined to use the clinic for delivers if it was free, she reported:

If the clinic was free, I would go, I will go anywhere that is free.

A general sentiment among everyone interviewed was the fact that nurses are overworked and decreasing the ratio of SBAs to patients can relieve some stress on care teams. Also, it may improve SBAs attitudes with patients allowing SBAs the time to attend to each patient properly, and combat SBA burn out. A husband described the experience of understaffed SBAs:

You may have 5 patients to attend to at the same time, and the facilities do not have the capacity. You may not have the supplies you need, so you are getting frustrated; and your delay causes patients to shout increasing your frustration.

SBAs were in agreement that a negative attitude among the healthcare team plays a role in women’s apprehension to use clinics.

I think that is what is driving them away, we must also work on our attitude. More empathetic to our clients.

During an FGD, SBAs recommended studying the techniques of TBAs, and adopting their non-harmful practices to improve women’s birth experiences.

Because you cannot rule out traditional belief, if it is not harmful, why not. I think we also need to at least study, let’s know these beliefs and add the ones that are not harmful into our own practice.

Discussion/Implications

This study provides the first qualitative evidence of women’s birthing preferences in Nigeria. Understanding these preferences will allow Nigeria’s maternal healthcare system to develop methods to accommodate them, thereby increasing healthcare facility usage for childbirth. This study found that women have to balance a host of factors when deciding where to deliver. Most women indicated that they want a birthing experience that is dignified, results in a healthy baby, and is within their cultural scope, other factors like gender of their birth attendant were far less important. Contrary to some studies indicating that healthcare facility cost is the predominant motivating factor for the use of TBAs, the women interviewed report this factor playing a less significant role.19 20

Study findings are consistent with other studies that indicate women’s preference for childbirth outside of healthcare facilities is associated with maltreatment by SBAs in healthcare facilities.21–23 Abuse of women in Nigeria within clinical settings including physical abuse, restraining women and verbal abuse such as shouting is common practice.21 22 During interviews many women who chose to deliver with TBAs did so because they believed that they would receive more dignified treatment than they would in a healthcare facility with an SBA. Women at times travelled further and paid more for services to use TBAs. Even women who chose to use SBAs reported maltreatment, but the risk of poor birth outcomes outweighed their concerns for abuse.

Delivering respectful care during childbirth by SBAs has been shown to increase the usage of healthcare facilities.24 However, nurses admit to having negative attitudes towards labouring women, and believe that retraining will improve their attitudes.25 26 Thus SBAs should be educated on the implications of their behaviour on healthcare facility usage. Additionally, they can be retrained regarding professionalism and how to provide women-centred care.

In addition, allowing women to bring labour companions can provide them with desired emotional and cultural support during labour. Importantly, women who receive emotional support during labour tend to have quicker labour, better pain management and require less medical intervention.27 Because SBAs reported being stressed and short staffed, requesting them to also act as labour companions would only further overextend them.28 Hospital policies should consider accommodating labour companions for all women. Studies conducted in Nigeria showed that women would like a policy that would allow labour support from family and friends.27 Due to cultural norms and the lack of privacy in many healthcare facilities, many birthing attendants believe that male birthing companions would be inappropriate; however, female birthing companions should be accommodated.29 30

System level implications of our study include efforts placed on integrating cultural practices and TBAs into local healthcare systems to increase usage of healthcare facilities.31 32 Many women appreciated the security that delivering in a healthcare facility provided but opted to use TBAs for a more cultural experience.33 34 Healthcare facilities can neglect cultural needs, and traditional practices in exchange for standardised protocol.35 To adopt more Western standards of practice, healthcare systems in Nigeria may have done so at the expense of cultural sensitivity in the form of traditional medicinal practices36 37 Efforts should be made to develop a maternal healthcare system in Nigeria that is inclusive of both Western biomedicine and traditional practices.

This study had several limitations. One is the possibility of recall bias of participants, given that most were asked to recall incidents that occurred weeks of even years ago. Cultural bias is another possible limitation. Although many similarities exist between different tribal groups in Nigeria, and despite trying to ensure cultural competence the PI’s Yoruba American ethnicity may influence data interpretation. Another limitation of this study was the lack of educational and financial diversity among the husbands who participated in the FGD. Men were recruited on the University of Benin campus and therefore not representative of the general Benin City’s population.

However, the strength of this study is that it is the first known qualitative study to explore the childbirth preferences of women and the social and cultural factors that influence those preferences in Nigeria. Additionally, the study’s findings regarding treatment of women by SBAs is consistent with other published works.

Conclusion

A woman’s labour preference is determined by what factors she prioritises, and the birthing method she perceives will prioritise those same factors. That, along with the influence of unpredictable situations such as rapid labour and unstaffed clinics, determined whether women deliver in healthcare facilities with SBAs or with TBAs. The women of Benin City, Nigeria, were far more concerned with delivering a healthy baby in a supportive and culturally competent environment, than factors such as modesty or spiritual needs. To encourage the transition from prenatal care to childbirth in a healthcare facilities a women-centred approached must be adopted. Healthcare system in Nigeria should retrain SBAs, and integrated non-harmful cultural practices; this will allow women the option to deliver a baby within a clinic setting, in a manner that is emotionally supportive, and within their cultural scope.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to the women, husbands, SBA and TBAs who participated in this study. Thank you also to Dr Marteen Bosland, Kathleen Anaza and Cortez Alexander who provided feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @feokonofua

Contributors: DE and FO developed the research question. DE and SW designed the experiment. DE carried out the experiment and data transcription and analysis. DE wrote the manuscript with input from FO, SW and GG. DE is the study guarantor and overall resonsiple of study content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All relevant data is including in manuscript and supplements documents, no additional data is available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by University of Illinois at Chicago: Protocol # 2019-0683, College of Medical Science University of Benin: CMS/REC/2019/082. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.The World Health Organization . Maternal morality. 2018. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/measurement-matters-the-decline-of-maternal-mortality

- 2.Zureick-Brown S, Newby H, Chou D, et al. Understanding global trends in maternal mortality. International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health 2013;39:32–41. 10.1363/3903213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO U. UNFPA, world bank group and the United Nations population division. In: Trends in maternal mortality. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okonofua F, Imosemi D, Igboin B, et al. Maternal death review and outcomes: An assessment in Lagos state, Nigeria. Plos one 2017;12:e0188392. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okonofua F, Randawa A, Ogu R, et al. Views of senior health personnel about quality of emergency obstetric care: A qualitative study in Nigeria. Plos one 2017;12:e0173414. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okonofua FE, Ntoimo LFC, Ogu RN. Women’s perceptions of reasons for maternal deaths: Implications for policies and programs for preventing maternal deaths in low-income countries. Health care for women International 2018;39:95–109. 10.1080/07399332.2017.1365868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Bank . Births attended by skilled health staff. 2018. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.BRTC.ZS

- 8.Okonofua F, Ogu R, Agholor K, et al. Qualitative assessment of women’s satisfaction with maternal health care in referral hospitals in Nigeria. Reproductive health 2017;14:44. 10.1186/s12978-017-0305-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlough M, McCall M. Skilled birth attendance: What does it mean and how can it be measured? A clinical skills assessment of maternal and child health workers in Nepal. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2005;89:200–8. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.12.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakua EK, Sevugu JT, Dzomeku VM, et al. Home birth without skilled attendants despite millennium villages project intervention in Ghana: Insight from a survey of women’s perceptions of skilled obstetric care. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 2015;15:243. 10.1186/s12884-015-0674-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anastasi E, Borchert M, Campbell OMR, et al. Losing women along the path to safe motherhood: Why is there such a gap between women’s use of Antenatal care and skilled birth attendance? A mixed methods study in northern Uganda. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 2015;15:287. 10.1186/s12884-015-0695-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Titaley CR, Hunter CL, Dibley MJ, et al. Why do some women still prefer traditional birth attendants and home delivery?: A qualitative study on delivery care services in West Java province, Indonesia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 2010;10:43. 10.1186/1471-2393-10-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibley LM, Sipe TA, Barry D. Traditional birth attendant training for improving health Behaviours and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2012;8:CD005460. 10.1002/14651858.CD005460.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geleto A, Chojenta C, Musa A, et al. Barriers to access and utilization of emergency obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of literature. Systematic reviews 2018;7:183. 10.1186/s13643-018-0842-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moshi F, Nyamhanga T. Understanding the preference for Homebirth; an exploration of key barriers to facility delivery in rural Tanzania. Reproductive health 2017;14:132. 10.1186/s12978-017-0397-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumbani L, Bjune G, Chirwa E, et al. Why some women fail to give birth at health facilities: A qualitative study of women’s perceptions of perinatal care from rural Southern Malawi. Reproductive health 2013;10:9. 10.1186/1742-4755-10-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirose A, Owolabi O, Imamura M, et al. Systematic review of obstetric care from a Women‐Centered perspective in Nigeria since 2000. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2017;136:13–8. 10.1002/ijgo.12007 Available: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ijgo.2017.136.issue-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE open medicine 2019;7:205031211882292. 10.1177/2050312118822927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarker BK, Rahman M, Rahman T, et al. Reasons for preference of home delivery with traditional birth attendants (Tbas) in rural Bangladesh: A qualitative exploration. Plos one 2016;11:e0146161. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allou LAchageba. Factors influencing the utilization of TBA services by women in the Tolon District of the northern region of Ghana. Scientific African 2018;1:e00010. 10.1016/j.sciaf.2018.e00010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Tunçalp Ö, et al. Mistreatment of women during childbirth in Abuja, Nigeria: A qualitative study on perceptions and experiences of women and healthcare providers. Reproductive health 2017;14:9. 10.1186/s12978-016-0265-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okafor II, Ugwu EO, Obi SN. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income country. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2015;128:110–3. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishola F, Owolabi O, Filippi V. Disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth in Nigeria: A systematic review. Plos one 2017;12:e0174084. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galadanci HS, et al. Programs and policies for reducing maternal mortality in Kano state, Nigeria: A review. African Journal of reproductive health 2010;14:31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onasoga OA, et al. Factors influencing Midwives' attitude towards women in labour in selected hospitals in niger Delta region of Nigeria. Tropical Journal of health sciences 2018;25:40–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farotimi AA, Ajao EO, Ademuyiwa IY, et al. Effectiveness of training program on attitude and practice of infection control measures among nurses in two teaching hospitals in Ogun state, Nigeria. Journal of education and health promotion 2018;7:71. 10.4103/jehp.jehp_178_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fathi Najafi T, Latifnejad Roudsari R, Ebrahimipour H, et al. The best encouraging persons in labor: A content analysis of Iranian mothers' experiences of labor support. Plos one 2017;12:e0179702. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James OE, Emmauel NA, Ademuyiwa IY. Challenges, and nurses’ job performance in the University of Calabar teaching hospital, Calabar cross River state Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dim CC, Ikeme AC, Ezegwui HU, et al. Labor support: An overlooked maternal health need in Enugu, South-Eastern Nigeria. The Journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine 2011;24:471–4. 10.3109/14767058.2010.501121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adeniran A, Adesina K, Aboyeji A, et al. Attitude and practice of birth attendants regarding the presence of male partner at delivery in Nigeria. Ethiopian Journal of health sciences 2017;27:107–14. 10.4314/ejhs.v27i2.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Afulani P, Kusi C, Kirumbi L, et al. Companionship during facility-based childbirth: Results from a mixed-methods study with recently delivered women and providers in Kenya. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 2018;18:150.:150. 10.1186/s12884-018-1806-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chi PC, Urdal H. The evolving role of traditional birth attendants in maternal health in post-conflict Africa: A qualitative study of Burundi and northern Uganda. SAGE open medicine 2018;6:2050312117753631. 10.1177/2050312117753631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U S, E A. Integration of traditional birth attendants (Tbas) into the health sector for improving maternal health in Nigeria: A systematic review. Sub-Saharan African Journal of medicine 2019;6:55. 10.4103/ssajm.ssajm_25_17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adatara P, Strumpher J, Ricks E, et al. Cultural beliefs and practices of women influencing home births in rural northern Ghana. International Journal of women’s health 2019;11:353–61. 10.2147/IJWH.S190402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esienumoh EE, Akpabio II, Etowa JB, et al. Cultural diversity in childbirth practices of a rural community in Southern Nigeria. J Preg child health 2016;3:2. 10.4172/2376-127X.1000280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ibeneme S, Eni G, Ezuma A, et al. Roads to health in developing countries: Understanding the intersection of culture and healing. Current therapeutic research 2017;86:13–8. 10.1016/j.curtheres.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdullahi AArazeem. Trends and challenges of traditional medicine in Africa. African Journal of traditional, complementary and alternative medicines 2011;8(5 Suppl):115–23. 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-054603supp001.pdf (140.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All relevant data is including in manuscript and supplements documents, no additional data is available.