Abstract

Objective: Perfectaionism is a common personality trait that can affect various aspects of life, especially sexual relationships. The purpose of this systematic review was to summarize the existing evidence for the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function in studies conducted in Iran and the world.

Method : A comprehensive search of databases such as Scopus, PubMed, Cochrane, Science Direct, ProQuest, PsychINFO, IranPsych, Irandoc, SID, and Google Scholar search engine was performed until December 2021 without a time limit. To find studies, we searched for the keywords perfectionism and sexual function in both Persian and English and combined these words with the AND operator. Studies that scored above 15 according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) criteria were included. Data analysis was performed qualitatively.

Results: From the total of 878 articles found in databases, six articles met the inclusion criteria and had moderate quality. Reviewing studies corroborated that, notwithstanding the positive association between general/sexual perfectionism and sexual desire, specific dimensions such as socially prescribed perfectionism, partner-prescribed, and socially prescribed sexual perfectionism, have the utmost unfavorable effect on female sexual function, which means that a higher level of perfectionism ultimately decreases the rate of sexual function in women. In addition, studies suggested that by increasing sexual anxiety and distress levels, perfectionism deteriorates sexual function.

Conclusion: Perfectionism may cause a variety of problems regarding sexual function. However, to clarify the precise role of each dimension of perfectionism on different areas of sexual function, more research must be conducted in this area in various communities and on age groups other than females of reproductive ages.

Key Words: Perfectionism, Sexuality, Sexual Behavior, Sexual Activity, Systematic Review

Sexual activity is a basic human need that also has a reproductive function (1). Interpersonal, psychological, and sociocultural factors play a significant role in causing sexual difficulty, sexual concern, and continuation of sexual dysfunction for an extended period (2). Sexual function is a collection of interactions of both endocrine and neurovascular systems that can be affected by many factors, including interpersonal relationships, environment, biological characteristics, and traditional and cultural factors (3). Sexual dysfunction is defined as a disturbance in sexual desire and the sexual response cycle that can cause interpersonal difficulty and marked distress (4). This description is mainly based on the human sexual response cycle, which indicates the coordination of multiple stages, such as sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and satisfaction (5).

A Perfectionistic personality sets very high standards for their performance, strives for flawlessness, is too worried about negative evaluations by others, and has a desire for excessively critical self-evaluations (6, 7). Perfectionism is a multidimensional personality structure that makes one prone to distress and psychopathology (8–11). The maladaptive form of perfectionism yields a variety of negative consequences, including depression, anxiety, and stress (12). Hewitt and Flett (1991) reported an operational model to measure multidimensional perfectionism. Regarding their model, perfectionism has social and personal aspects which are differentiated into three forms such as self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed. In self-oriented perfectionism, a person expects nothing but perfection from him/herself. Self-oriented perfectionism represents the importance of being perfect and striving for perfection. In other-oriented perfectionism, a person wants others to act perfectly. Other-oriented perfectionism means the idea that others must attempt to behave or perform in a perfect way that meets one’s high standards. Ultimately, socially prescribed perfectionism means one’s idea that others want him/her to be perfect, and being accepted by others is conditional on fulfilling their high standards (9, 13).

Perfectionism is a common personality trait that can affect all areas of life, especially sexual relationships (14), and is associated with a variety of consequences for sexual function (15). Primary evidence suggests that different forms of sexual perfectionism (perfectionism ascribed to sex) (16) affect sexual function regarding their association with positive (e.g., closeness, sexual esteem, sexual efficacy) and negative (e.g., sexual problem self-blame, sexual anxiety, negative attitudes towards sex) aspects of sexuality (17, 18). Considering this, Stoeber et al. (2013) exhibited that socially prescribed and partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism impaired sexual function by their interdependence on sexual problem self-blame. On the other hand, self-oriented and partner-oriented sexual perfectionism acted as ambivalent forms of perfectionism according to their relation to sexual problem self-blame, and sexual esteem (17). Habke et al. (1999) indicated that not only the female’s rating of other-oriented perfectionism, socially prescribed perfectionism, and perfectionistic self-presentation, but also her husband’s rating of socially prescribed perfectionism impaired her sexual satisfaction. The husband’s rating of socially prescribed perfectionism and his wife’s rating of other-oriented perfectionism negatively impaired his sexual satisfaction (19). Sexually dysfunctional men, specifically those who develop secondary erectile dysfunction (SED), tend to have perfectionistic thinking and a self-blaming perspective concerning sexual situations (16). Perfectionism becomes destructive when one starts to evaluate and monitor his/her performance or appearance during sex (Spectatoring) (19, 20). Partner or self-imposed evaluations during sex generate performance problems attributed to arousal/erection, ejaculation, body image, and orgasm (21, 22). Moreover, these evaluations are correlated with increased sexual anxiety in all domains (23). According to the evidence mentioned earlier, perfectionism is a multidimensional personality trait that can affect sexual function. Albeit, it has not been comprehensively explored yet in the area of sexuality (17). To the best of our knowledge, there has not yet been a study developed to mainly summarize all the information about the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function; so, a review on this topic remains scarce. Therefore, the present study aimed to systematically review the studies on the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function.

Materials and Methods

Methodology

This article was compiled using PRISMA guidelines in 5 steps, including designing a research question, conducting an extensive search of various databases, evaluating the quality of the research, summarizing the evidence obtained from studies, and a brief interpretation of the results (24).

Literature Search

An extensive search was done through English databases including Scopus, PubMed, Cochrane, Science Direct, ProQuest, PsychINFO and the Google Scholar search engine, as well as Iranian databases such as IranPsych, Irandoc, and the Scientific Information Databases (SID) to find articles related to the purpose of the study. The search was performed without a time limit and until December 2021. The search strategy included Latin transcription of the keywords “Perfectionism”, “Sexual Function”, and “Sexual activity” (for international databases) and their Farsi translation (for Iranian databases). The combination of these words was as follows: (Sexual activity OR Sexual Function) AND (Perfectionism).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria of the study were: Farsi or English language articles that have assessed the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function with appropriate tools. Exclusion criteria were: not evaluating the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function; no precise data; studies of poor quality; the lack of access to the full text of the article; short articles; review articles; and conference abstracts.

Data Analysis

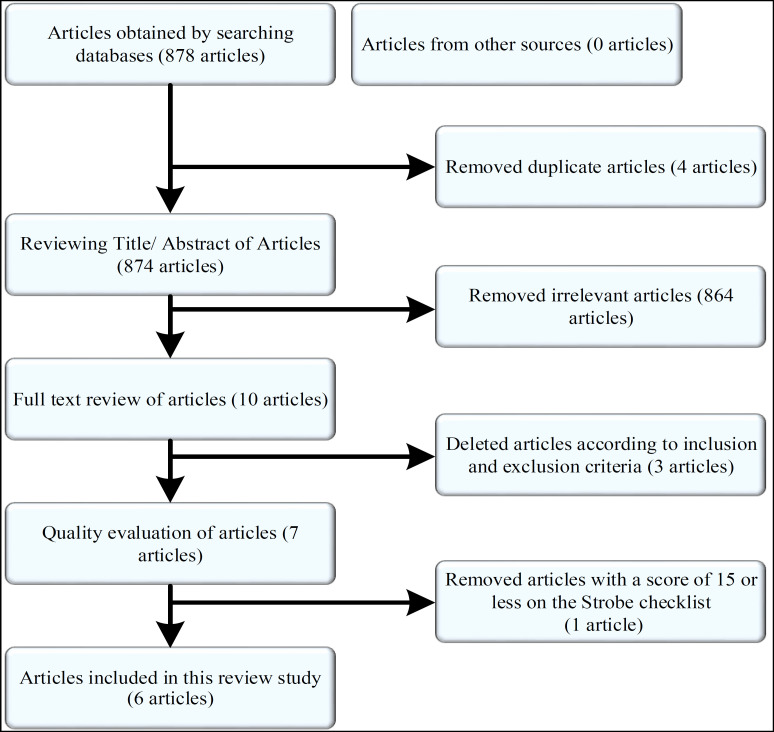

In the initial search, 878 articles were found, and after removing duplicates, the title and abstract of 874 articles were reviewed. 864 articles were removed due to irrelevance, and the full text of 10 articles was reviewed. 3 articles were excluded from the study because of the absence of the inclusion criteria and based on the exclusion criteria. 7 studies entered the qualitative evaluation stage (Strobe checklist), 1 of which was excluded because of poor quality, and finally, 6 articles were included in the study. Eventually, the full text of 6 articles was selected for the present review. To prevent any bias, all stages of the research and the extraction of original articles were performed by two researchers independently (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the Search Phases to Select Studies for Systematic Review Based on the PRISMA Statement

To evaluate the quality of the included articles, the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist was used. This checklist consists of 22 items in the form of six general sections, including title and article abstract (item 1), introduction (items 2 and 3), methods (items 4-12), results (items 13-17), discussion (items 18-21) and other cases (item 22 about funding and financial resources) (25). For each of the 22 items, if its content was acceptable enough, it was given a score of 1, otherwise, a score of 0 was assigned. In this study, the final score of the checklist was 30. Research with 75% or more of the maximum assignable score (score 23 or more) is considered "high quality", research with a score between 75% -50% (score 22-16) is considered "average quality", and research with a score less than 50% (score 15 and less) is considered as "low quality" research (26). According to this checklist, studies of medium and high quality were included in this review study. The quality of articles and their scoring were evaluated separately by two researchers of this article. In case of any disagreement in scoring the items, the final score was considered in a joint meeting with the third researcher. The results from the quality evaluation of those six articles are presented in Table 1.

able 1.

Characteristics of the Studies on Perfectionism and Sexual Function

|

Author / Year /

Reference number |

location of the

study |

Type of Study | Purpose of the study | Sample size |

Research

instruments |

Results |

Article quality

based on STROBE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunkley et al. (2019) (30) |

America | Cross-sectional | Investigating the association between disordered eating and sexual functioning, with an emphasis on sexual pain and distress |

581 female undergraduate students in the age group of 19 years and above |

FSFI, MPQ, EDI-3 |

Perfectionism was positively correlated with FSFI in the area of sexual desire (r = 0.10, p < 0.01), FSDS total (r = 0.15, p < 0.001), and Vulvar Pain Unpleasantness (r = 0.13, p < 0.01), and negatively correlated with FSFI pain (r = −0.10, p < 0.05 |

20 |

| Chloe et al. (2018) (27) |

America | Cross-sectional | Testing the role of perfectionism in attachment style and sexual function in women |

501 female undergraduate students in the age group of 18 years and above |

MSPQ, SAI-E |

Interpersonal perfectionism was associated with poorer sexual function. Socially prescribed perfectionism (r = −0.13, p = 0.005) and nondisclosure of imperfections (r = −0.17, p < 0.01) were associated with lower sexual arousal and were the strongest forms of perfectionism in anticipating sexual anxiety and sexual arousal. |

17 |

| Grauvogl et al. (2018) (28) |

Netherlands | Cross-sectional | Associations Between Personality Disorder Characteristics, Psychological Symptoms, and Sexual Functioning in Young Women |

188 women aged 18 to 25 years |

FSFI, ADP-IV |

Maladaptive personality disorders such as cluster C, including a perfectionistic personality can disturb sexual function in the area of satisfaction (r = −0.014, P < 0.05). Also, they can be considered a persistent vulnerability factor in the promotion and recurrence of sexual dysfunction. |

22 |

| Stoeber et al. (2016) (31) |

England | Longitudinal | Examining whether multidimensional sexual perfectionism predicts changes in sexual self- concept and sexual function over time |

366 women between the ages of 17-69 (university students) |

MSPQ, FSFI |

The cross-sectional data revealed that there is a positive relationship between partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism and sexual pain (r = 0.21, P < 0.001). Also, there are negative relationships with arousal (r = −0.18, P < 0.01), lubrication (r = −0.22, P < 0.001), and orgasmic function (r = −0.17, P < 0.01). Longitudinal findings suggested that partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism is a maladaptive form of sexual perfectionism that disturbs female sexual function in the area of arousal (r = −0.28, P < 0.001), lubrication (r = −0.23, P < 0.01), and satisfaction (r = −0.17, P < 0.05) over time. |

20 |

| Kluck et al. (2016) (18) |

America | Cross-sectional | Examining the relationships between dimensions of sexual perfectionism and communication about sex, sexual functioning, and appearance self- consciousness during sex |

208 women aged 19 to 59 years |

MSPQ, FSFI |

The dimensions of sexual perfectionism showed a complex pattern of relationships regarding sexual function. Partner-prescribed and socially prescribed SP do not affect sexual function directly, but only indirectly (through greater appearance self- consciousness, and poor dyadic communication about sex). All four dimensions of sexual perfectionism were associated with better performance in the area of sexual desire ( r = 0.23, P < 0.01) |

20 |

| Aghamohammdian et al. (2014) (29) |

Iran | Cross-sectional | Investigating the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function in infertile women |

179 Infertile woman |

MSPQ, FSFI |

There was a significant negative correlation between the dimensions of perfectionism (Self-oriented (r = −0.632, P < 0.001), Other-oriented (r = −0.659, P < 0.001), and Socially prescribed perfectionism (r = −0.713, P < 0.001)) and the sexual function of infertile women. In the interaction of perfectionism dimensions, socially prescribed perfectionism was the supreme significant predictor of sexual function (β = −0.471, p = 0.014) |

23 |

FSFI: Female Sexual Function Questionnaire; MPQ: McGill Pain Questionnaire; EDI-3: Eating Disorders Inventory-3 (Measuring Attitudes, Personality Traits, and Severity of Eating Disorders); FSDS: Female Sexual Distress Scale; MSPQ: Multidimensional Sexual Perfectionism Questionnaire; SAI-E: Sexual Arousability Inventory-Expanded; ADP-IV: The Assessment of DSM-IV-TR Personality Disorders Questionnaire; MPS: Multiple Perfectionism Scale.

Using the prepared checklist, two authors of the present study extracted the required data separately. The checklist included the author’s name, type of study, place of study, year of research, research purpose, sample size, study instruments, and results (Table 1).

Results

The present review study consisted of 6 articles, of which 5 were cross-sectional (18, 27–30) and one was longitudinal (their results had been divided into two-time categories (the preliminary and longitudinal (3-6 months later) assessments)) (31). Three of the included articles were conducted in the United States (18, 27, 30), one in the Netherlands (28), one in the United Kingdom (31), and one in Iran (29). Among these articles, 5 articles were in English, and 1 article was in Farsi, and their qualities were estimated to be high or moderate. In 4 articles, the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function (27–30), and in 2 articles, the relationship between sexual perfectionism and female sexual function had been assessed (18, 31). The results of the review of the studies are categorized into the following six general sections:

Sexual Desire

Dunkley et al. (2019) indicated that Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) desire was positively correlated with perfectionism (30). Correspondingly, Kluck et al. (2016) illustrated that all four dimensions of sexual perfectionism were associated with better sexual functioning in the area of sexual desire (18). Similarly, in the preliminary assessment, Stoeber and Harvey (2016) authenticated that self-oriented, partner-oriented, and socially prescribed sexual perfectionism were positively related to sexual desire (31).

Sexual Arousal

Regarding female sexual arousal, the findings of Chloe et al. (2018) demonstrated that nondisclosure of imperfection (one’s deliberate prohibition of any verbal admission of his/her imperfection) and socially prescribed perfectionism had a negative correlation with sexual arousal. Also, these two dimensions of perfectionism were the strongest predictors of sexual arousal (27). Likewise, Stoeber and Harvey (2016) manifested that partner-directed and partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism in primary assessments, and partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism in longitudinal (3-6 months later) assessments, were negatively associated with sexual arousal (31).

Sexual Satisfaction

According to Grauvogl et al. (2018), cluster C personality characteristics, including a perfectionistic personality, impair female sexual function in the area of satisfaction (28). These results match the findings of Stoeber and Harvey (2016), indicating that all dimensions of sexual perfectionism had a negative correlation with sexual satisfaction (31).

Sexual Lubrication and Orgasm

In Stoeber and Harvey’s (2016) preliminary results, partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism was the most negative dimension in correlation with lubrication and orgasm. Also, in their longitudinal (3-6 months later) outcomes, partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism was the only dimension that was negatively correlated with lubrication (31).

Sexual Pain

In respect of FSFI pain, Dunkley et al. (2019) indicated a negative correlation between perfectionism and FSFI pain (30); on the other hand, the primary assessment by Stoeber and Harvey (2016) demonstrated a positive relationship between partner-prescribed and socially prescribed sexual perfectionism and FSFI pain (31).

General Sexual Function

In the matter of impairing sexual function in general, Grauvogl et al. (2018) represented that cluster C personality characteristics, including a perfectionistic personality, seemed to be the remaining vulnerability factors in the development and repetition of sexual dysfunction (28). Stoeber and Harvey (2016) vindicated that self-oriented and partner-oriented sexual perfectionism are two ambivalent forms of sexual perfectionism correlated with both positive and negative aspects of sexuality. Furthermore, socially prescribed sexual perfectionism in the primary assessment and partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism in both primary and longitudinal (3-6 months later) assessments appeared as the most destructive forms regarding sexual function (31). Kluck et al. (2016) corroborated an intricate pattern between dimensions of sexual perfectionism and adaptive sexual functioning. Their outcomes asserted that socially prescribed and partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism deteriorated sexual function by their indirect effect through greater self-consciousness about physical appearance (SCPA) and poor dyadic communication about sex (18). Aghamohammdian et al. (2014) concluded that there was a negative relationship between self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism and sexual function in infertile women, meaning that the higher rate of perfectionism consequently leads to poorer sexual function in infertile women. Furthermore, through all facets of perfectionism, socially prescribed perfectionism was the most critical form in predicting infertile women’s sexual dysfunction (29).

Findings of various studies suggest that increased sexual distress (30) and anxiety levels, perfectionism in the form of socially prescribed perfectionism (27, 29, 31), and partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism have induced adverse effects on sexual function (31).

Discussion

The present study aimed to systematically review the studies on the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function in both English and Farsi languages. Results established that concerning the dimension, perfectionism acts as a double-edged sword regarding the areas of sexual function. Accordingly, despite the positive correlation between general (30) and sexual perfectionism with sexual desire (18, 31), the chief impact of this personality characteristic on female sexual function is considered to be negative (18, 27–30, 32). In other words, most studies substantiated that perfectionism has established or perpetuated sexual function problems (17, 27, 28, 33), and increased perfectionism in women leads to decreased sexual function (29). Socially prescribed perfectionism as well as partner-prescribed and socially prescribed sexual perfectionism acted as the most destructive/ incompatible dimensions of perfectionism by diminishing sexual arousal and satisfaction and elevating sexual pain and anxiety levels (18, 27, 29, 31).

To justify the conclusions, it can be argued that primarily perfectionist concerns are characterized by neuroticism, low agreeableness, and extraversion. Hence, people with high perfectionist concerns are usually jealous, anxious, emotionally insecure, and susceptible to maladaptive coping responses and dysfunctional thinking. Existing evidence suggests that perfectionistic concerns are an explicit negative form of perfectionism followed by illogical beliefs, maladjustment, and psychological distress (10, 11, 34, 35). Sexual perfectionism refers to the idea that if a partner is not performing perfectly in sex, he/she has failed. Also, to be accepted by their sexual partner, perfectionists pose this obligation on themselves to be sexually perfect (36). In the same direction, the concept of "spectatoring" has been described by Masters and Johnson (1970) as having cognitive distractions in the form of excessive monitoring of one's sexual performance (20). Spectatoring in women is along with self-evaluation of appearance during sexual intercourse (37), leading to acting as an observer rather than a participant, focusing on self rather than the erotic cues supplied by the partner, and eventually hindering sexual arousal and orgasm (20). The critical elements of spectatoring are partner- or self-imposed evaluations and expectations to be a perfect sexual partner (18, 37), which ultimately increase sexual anxiety (23). With that knowledge in mind, socially prescribed and partner-prescribed sexual perfectionism impose their deleterious indirect effect on sexual function through enhancing self-consciousness about physical appearance (SCPA) and lowering dyadic communication about sex (18). Therefore, these dimensions can be strong predictors of sexual performance anxiety, which subsequently will cause sexual dysfunction (31, 38) and relationship dissatisfaction (39). On the other hand, according to the human sexual response cycle (40), these facets of sexual perfectionism augment pain during sexual intercourse by debilitating two indicators of the excitement stage, such as arousal and lubrication (31). Moreover, as they reduce lubrication, they can be considered as psychological factors of Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder (40).

Sexual satisfaction is a substantial aspect of female sexual function (41), which is experienced with or without orgasm when the women can stay concentrated, and stimulation remains sufficiently long (42). Research documents the bidirectional correlation between relationships and sexual satisfaction, meaning that they are longitudinally and dynamically interconnected (43). Correspondingly, Stoeber (2012) implicated that perfectionism in students’ romantic relationships negatively affected their relationship satisfaction (39). The outcome of a review study showed that there is a significant relationship between perfectionism and dyadic relationship (i.e., a couple who have a romantic relationship or a married couple). Also, spouses with normal perfectionism have more marital satisfaction, and spouses with abnormal perfectionism have less marital satisfaction and more dyadic conflict (32). Perfectionists have more fear of intimacy; hence they experience less marital satisfaction (44). Habke et al. (1999) suggested that both husbands’ and wives’ sexual satisfaction were negatively associated with interpersonal dimensions of perfectionism (19). In parallel with the knowledge mentioned above and concerning the impact of perfectionism on men’s sexual function, erectile dysfunction in men is related to their belief that they should always perform perfectly in a sexual situation (16). DiBartolo et al. (1996) displayed that due to psychogenic variables, higher levels of perfectionism in women (rather than men) were associated with higher clinical degrees of erectile dysfunction in men. Additionally, the overall perfectionism scores of dysfunctional men were not a predictive factor for their own or their wife’s marital satisfaction. However, perfectionistic tendencies in women influenced their and their husband’s marital satisfaction (45). Fernandes et al. (2019) implicated that perfectionistic thinking patterns, only in the form of socially prescribed perfectionism, are related to poor sexual satisfaction (46). Altogether, it can be assumed that perfectionism adversely affects sexual satisfaction through increased relationship dissatisfaction (39) and decreased dyadic adjustment/communication (18, 19, 45).

The discrepancy in the results is presumably because pleasure and, consequently, human sexual function are the product of the mind rather than the body. Therefore, problems such as anxiety, depression, fear, and anger can lead to sexual dysfunction (47). Besides, it is axiomatic that psychological and interpersonal factors are associated with the etiology and retention of sexual problems. Moreover, susceptibility to sexual disruption originates from personality characteristics, conditional/biological dispositions, psychiatric or medical illness, and the ability to extend and maintain an intimate relationship (48). Eventually, people with perfectionistic personalities should be candidates for stress management techniques/training or any treatment that concentrates precisely on teaching coping strategies. For instance, treatments based on improving coping and problem-solving skills are lucrative in reducing the stress response and its concomitant symptoms. Although these approaches may have resulted in advantages for handling the outcomes of perfectionistic behavior or managing stress, it is important to recognize the fact that this stress stems from perfectionism as a profound inveterate core vulnerability element (49, 50). With this knowledge in mind, the best-recommended treatment is psychotherapy which concentrates on the principal issues of perfectionism (50). Also, clinicians, psychologists, and all health care providers must be alert to identify any potential for unrealistic expectations and longing to be a perfect sexual partner when dealing with patients who complain about sexual problems (19).

Limitation

The primary limitation of the present study was that meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneous methodology of the studies. Besides, most of the included studies were cross-sectional, and their population consisted mostly of women of reproductive age. Considering this, the present review article has illustrated the consequences of perfectionistic behavior on female sexual function. Still, these sequelae could not be generalized to all female age groups, such as menopausal, postmenopausal, and older adults. Also, evidence on the association between perfectionism and male sexual function is still lacking. Taking all into consideration, future studies with higher sample sizes among other age groups (other than reproductive age) may provide different outcomes, clarify the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function more explicitly, and elucidate the remaining gaps.

Conclusion

A review of studies exhibited that, except for the area of sexual desire, the prime effect of perfectionism on female sexual function is negative. Therefore, women who complain about sexual dysfunction should be considered as candidates for managing stress and spotting the perfectionistic roots, in addition to medical treatments, psychotherapy, treatments based on problem-solving skills, and coping strategies. Besides, we suggest further research concerning the illumination of the role of perfectionism dimensions in a variety of sexual function problems in men and women of all age groups.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to all the researchers who worked on the determination of the relationship between perfectionism and sexual function, and contributed to enriching the research background.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest concerning this article's research, authorship, and/or publication.

References

- 1.Hanjani HD, Suryadi D. Correlation Between Multi-Dimensional Sexual Perfectionism and Sexual Satisfaction in Women Undergoing Long Distance Marriage. TICASH Atlantis Press. 2020:1091–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brotto L, Atallah S, Johnson-Agbakwu C, Rosenbaum T, Abdo C, Byers ES, et al. Psychological and Interpersonal Dimensions of Sexual Function and Dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2016;13(4):538–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fourcroy JL. Female sexual dysfunction: potential for pharmacotherapy. Drugs. 2003;63(14):1445–57. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363140-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, Derogatis L, Ferguson D, Fourcroy J, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163(3):888–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognit Ther Res. 1990;14(5):449–68. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flett GL, Hewitt PL. Perfectionism and maladjustment: An Overview of Theoretical, Definitional, and Treatment Issues. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 2002:5–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Mikail SF. Perfectionism: A relational approach to conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. Perfectionism: A relational approach to conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. Guilford Publications. 2017:336. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60(3):456–470. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MM, Sherry SB, Chen S, Saklofske DH, Mushquash C, Flett GL, et al. The perniciousness of perfectionism: A meta-analytic review of the perfectionism-suicide relationship. J Pers. 2018;86(3):522–42. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MM, Sherry SB, Rnic K, Saklofske DH, Enns M, Gralnick T. Are perfectionism dimensions vulnerability factors for depressive symptoms after controlling for neuroticism? A meta‐analysis of 10 longitudinal studies. Eur J Pers. 2016;30(2):201–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bieling PJ, Israeli AL, Antony MM. Is perfectionism good, bad, or both? Examining models of the perfectionism construct. Pers Individ Dif. 2004;36(6):1373–85. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS): Technical manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoeber J, Stoeber FS. Domains of perfectionism: Prevalence and relationships with perfectionism, gender, age, and satisfaction with life. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;46(4):530–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snell Jr WE, Rigdon KL. Chapter 15: The multidimensional sexual perfectionism questionnaire: Preliminary evidence for reliability and validity. New directions in the psychology of human sexuality: Research and theory. Cape Giradeau, MO: Snell Publications. Retrieved from. http://cstl-cla.semo.edu/wesnell/books/sexuality/chap15.htm .

- 16.Quadland MC. Private self-consciousness, attribution of responsibility, and perfectionistic thinking in secondary erecticle dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther. 1980;6(1):47–55. doi: 10.1080/00926238008404245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoeber J, Harvey LN, Almeida I, Lyons E. Multidimensional sexual perfectionism. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(8):1593–604. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kluck AS, Zhuzha K, Hughes K. Sexual Perfectionism in Women: Not as Simple as Adaptive or Maladaptive. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(8):2015–27. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0805-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habke AM, Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Perfectionism and sexual satisfaction in intimate relationships. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1999;21(4):307–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Premature ejaculation. Human sexual inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown; 1970. pp. 92–115. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aubin S, Heiman JR. The handbook of sexuality in close relationships. Psychology Press; 2004. Sexual dysfunction from a relationship perspective; pp. 487–28. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowland DL, Strassberg DS, de Gouveia Brazao CA, Slob AK. Ejaculatory latency and control in men with premature ejaculation: an analysis across sexual activities using multiple sources of information. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowland DL, Van Lankveld JJ. Anxiety and performance in sex, sport, and stage: Identifying common ground. Front Psychol. 2019;10(1):1615–36. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balochi H, Hadizadeh Talasaz F, Bahri N. Donors’ Satisfaction with Egg Donation and Willingness to Re-donation: A Systematic Review Article. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2020;23(9):85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam NC, Hewitt P. Testing the Role of Perfectionism in Attachment Style and Sexual Functioning in Women. Undergrad J Psychol. 2018;5:27. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grauvogl A, Pelzer B, Radder V, van Lankveld J. Associations Between Personality Disorder Characteristics, Psychological Symptoms, and Sexual Functioning in Young Women. J Sex Med. 2018;15(2):192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.11.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aghamohammdian Sharbaf HR, Zarezade Kheibari S, Horouf Ghanad M, Hokm Abadi ME. The relationship between perfectionism and sexual function in infertile women. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil lity. 2014;17(97):9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunkley CR, Gorzalka BB, Brotto LA. Associations Between Sexual Function and Disordered Eating Among Undergraduate Women: An Emphasis on Sexual Pain and Distress. J Sex Marital Ther. 2020;46(1):18–34. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2019.1626307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stoeber J, Harvey LN. Multidimensional Sexual Perfectionism and Female Sexual Function: A Longitudinal Investigation. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(8):2003–14. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0721-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Totonchi M, Hassan S. Perfectionism and dyadic relationship: A systematic review. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci. 2018;7(14):472–85. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snell Jr WE. meeting of the Southwestern Psychological Association. Houston, TX: 1996. Sexual perfectionism among single sexually experienced females; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellis A. The role of irrational beliefs in perfectionism. Psychology. 2002:158–73. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stoeber J, Otto K. Positive conceptions of perfectionism: approaches, evidence, challenges. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2006;10(4):295–319. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahimi F, Atashpour H, Golparvar M. Predicting divorce tendency based on need to love and survival, sexual awareness and sexual perfectionism in couples divorce applicant. Sci J Soc Psychol. 2020;8(55):113–22. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiederman MW. “Don’t look now”: The role of self-focus in sexual dysfunction. Fam J. 2001;9(2):210–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCabe MP. The role of performance anxiety in the development and maintenance of sexual dysfunction in men and women. Int J Stress Manag. 2005;12(4):379–88. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoeber J. Dyadic perfectionism in romantic relationships: Predicting relationship satisfaction and longterm commitment. Pers Indiv Differ. 2012;53(3):300–5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simons JS, Carey MP. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions: results from a decade of research. Arch Sex Behav. 2001;30(2):177–219. doi: 10.1023/a:1002729318254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Basson R. Women's sexual dysfunction: revised and expanded definitions. Cmaj. 2005;172(10):1327–33. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quinn-Nilas C. Relationship and sexual satisfaction: A developmental perspective on bidirectionality. J Soc Pers Relat. 2020;37(2):624–46. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin JL, Ashby JS. Perfectionism and fear of intimacy: Implications for relationships. The Family Journal. 2004;12(4):368–74. [Google Scholar]

- 45.DiBartolo PM, Barlow DH. Perfectionism, marital satisfaction, and contributing factors to sexual dysfunction in men with erectile disorder and their spouses. Arch Sex Behav. 1996;25(6):581–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02437840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palha-Fernandes E, Alves P, Lourenço M. Sexual satisfaction determinants and its relation with perfectionism: A cross-sectional study in an academic community. Sex Relation Ther. 2022;37(1):100–14. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nazari S, Abolmaali K. The review of relationship between perfectionism (positive and negative) and self-esteem in predicting sexual satisfaction among married women. Iran J Nurs Res. 2015;28(95):11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Althof SE, Leiblum SR, Chevret-Measson M, Hartmann U, Levine SB, McCabe M, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2005;2(6):793–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Perfectionism and stress processes in psychopathology. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hewitt P, Flynn C, Mikail S, Flett G. Perfectionism, interpersonal problems, and depression in psychodynamic/interpersonal group treatment. Can Psychol. 2001;42(1):141–50. [Google Scholar]