Abstract

Purpose:

The success of genomic medicine hinges on implementation of genetic knowledge in clinical settings. In novel subspecialties, it requires that clinicians refer patients to genetic evaluation or testing, but referral is likely to be impacted by genetic knowledge.

Methods:

An online survey was administered to self-identified nephrologists working in the U.S.. Nephrologists’ demographic characteristics, genetic education, confidence in clinical genetics, genetic knowledge, and referral rates of patients to genetic evaluation were collected.

Results:

201 nephrologists completed the survey. All reported treating patients with genetic forms of kidney disease, but 37% have referred less than 5 patients to genetic evaluation. A third had limited basic genetic knowledge. Most nephrologists (85%) reported concerns regarding future health insurance eligibility as a barrier to referral to genetic testing. Most adult nephrologists reported insufficient genetic education during residency (65%) and fellowship training (52%). Lower rating of genetic education and lower knowledge in recognizing signs of genetic kidney diseases were significantly associated with lower number of patients referred to genetic evaluation (p-value<0.001). Most nephrologists reported that improving their genetic knowledge is important for them (>55%).

Conclusions:

There is a need to enhance nephrologists’ genetic education to increase genetic testing utilization in nephrology.

Keywords: genetic knowledge, education, genomic medicine, nephrology, patient referral

INTRODUCTION

With the expansion of medical genetics to novel specialties, non-geneticists are increasingly expected to be familiar with genetics and either directly offer genetic testing to their patients or refer them to genetic evaluations.1 However, studies indicate slower adoption than hoped. Even in medical specialties where genetic testing is recommended as part of routine care (e.g., women with ovarian cancer), widespread utilization has been limited, with the largest obstacle being lack of referral from the treating physician.2,3 Several barriers to the utilization of genetic testing have been attributed to clinician characteristics, including clinicians’ knowledge and skills in medical genetics.4,5 One of the sources of clinicians limited knowledge in genetics is the lack of genetic education in medical school. Although the Association of Professors of Human and Medical Genetics (APHMG) developed medical student genetics curriculum guidelines in 1998,6 analysis of genetics content in the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE®) in 2020 showed that the tests still focus on genetics as a basic science and not on the clinical relevance of medical genetics.7 And while a medical genetics curriculum for internal medicine residency training programs was published in 2004, it is unclear whether it was implemented.8

In nephrology, genetic testing has been performed in a limited number of clinical presentations for several decades,9 though research studies have increasingly demonstrated the relevance of genetic testing to individuals without classical phenotypes of genetic disorders.10,11 Identifying a genetic diagnosis in patients with kidney diseases can provide an etiology to individuals with kidney disease of unknown cause and has the potential to provide more targeted care, screen at-risk family members, and inform kidney donation. This new insight into otherwise unspecified etiologies of kidney disease has led to increased awareness of the potential of genetic testing as part of the standard nephrology diagnostic toolbox.10 Despite the growing accessibility of genetic testing in nephrology,12–14 it is not yet routinely offered to patients with kidney diseases, even pediatric patients who are more likely to have a genetic cause of nephropathy.

The evaluation of clinicians’ genetic knowledge to date has largely focused on oncologists and psychiatrists, and fewer studies exist on neurologists, cardiologists ophthalmologists, nurses and primary care physicians.5 Most demonstrated clinicians limited understanding of general genetic concepts, and four studies reported an inverse relationship between years of clinical practice and level of knowledge, suggesting an improvement in formal education of medical genetics.5 A few studies also explored nephrologists’ genetic education and genetic knowledge.15–17 In 2010, only 35% of U.S. nephrology fellows reported being well trained in genetic renal diseases.15 Although genetic testing can be used by nephrologists for patient diagnosis and care, as well as transplant planning and donation, a report in 2020 showed that genetics is currently not part of the nephrology fellowship curriculum in the US.18 A 2021 study reported a positive association between genetics education level of nephrologists in the U.S. and the number of genetic tests they ordered.17 In 2022, a Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference on Genetics in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) summarized desirable core competencies for nephrologists,19 such as ordering genetic tests and returning genetic results. However, the extent to which U.S. nephrologists are confident in applying genetics to their clinical work and referring patients to genetic evaluation is unknown.

Another documented barrier to referral for clinical genetic testing in the U.S. is clinician worry about genetic discrimination from employers and health insurance companies.20 Although the 2008 Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) may have assuaged some concerns, studies show lingering apprehensions about discrimination based on genetic diagnosis, potentially due to limited knowledge of GINA among clinicians and the general public.21,22 Neither the extent to which nephrologists are aware of the protections offered by GINA nor whether this knowledge impacts their decision to refer their patients to genetic evaluation is currently known.

This study surveyed U.S. nephrologists to explore key issues relating to genetic knowledge. We assessed nephrologists’ confidence and knowledge in genetics, rating of their genetic education, interest in further genetic education, and the association between their genetic education and referral to genetic evaluation. Given the distinct educational path of adult and pediatric nephrologists (internal medicine versus pediatric residencies) and the higher likelihood of pediatric patients having an underlying genetic renal disease, we analyzed the responses of pediatric and adult nephrologists separately. Although our survey focused on nephrologists, its findings are likely relevant for other subspecialities in clinical care. Medical curriculum has commonality across subspecialities and extending genomic education—and implementation—may be a shared challenge. Findings from our survey can thus inform larger efforts to increase clinicians’ referral to genetic evaluations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey design and content

The online survey was developed by an interdisciplinary team, including pediatric and adult nephrologists, a genetic counselor, and a bioethicist. Prior to the distribution, two adult and three pediatric nephrologists reviewed the survey and provided feedback on its clarity and comprehensiveness. The survey assessed nephrologists’ rating of their subjective knowledge (6 questions) and confidence (6 questions) in applying genetics in their clinic, their objective knowledge (6 questions) and their awareness of GINA (3 questions).23 Nephrologists also completed a short self-administered genetic literacy test (the Genetic Literacy Fast Test, GeneLiFT), which is formatted as a vocabulary recognition test and includes 31 real words (e.g. actionability, autosome, exome) and 20 non-words (e.g. chemosomal, potient, sequation).23 In addition, the survey queried about rating of their genetic education, methods utilized to improve genetic knowledge, and interest in expanding genetic education. Finally, the survey collected nephrologists’ demographic information and professional experience, including referral of patients to genetic evaluations. The survey was deployed on RedCap. The IRB at Columbia University Irving Medical Center approved the study.

Recruitment

To recruit nephrologists into the study, we collaborated with leading networks/organizations focusing on kidneys diseases, specifically the CureGlomerulopathy (CureGN) Network, the National Kidney Foundation (NKF), the Alport Syndrome Association (ASF), and the American Society of Pediatric Nephrologists (ASPN). These organizations circulated the online survey through their listservs between Jan.-May 2021. The survey was anonymous, but screening questions asked individuals to confirm their eligibility (i.e., nephrologists working in the U.S.). Individuals provided an online consent and were offered a $25 gift card for completing the survey.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with R software. For most variables, responses were categorized based on predefined categories to facilitate the results’ interpretation. For the genetic literacy analysis, only individuals who “recognized” at least 10 words or non-words were included. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the frequency of survey responses. Wilcoxon rank sum test and Chi-square test were used to assess statistical significance.

RESULTS

Individual’s characteristics.

116 adult nephrologists and 85 pediatric nephrologists competed the survey (Table 1). Most nephrologists were men (58%, n=117) and self-identified as non-Hispanic/Latino White (52%, n=104). More than a third of the nephrologists reported an additional advanced educational degree (36%, n=72). Only few nephrologists graduated from medical school less than 5 years ago (3%, n=7); half reported practicing nephrology for more than 16 years (50%, n=101). Most worked in university-affiliated hospitals (67%, n=135) and all nephrologists reported treating patients with genetic forms of kidney disease (Alport syndrome, Fabry disease, Polycystic Kidney Disease, Tuberous Sclerosis). Most nephrologists reported having referred patients to genetic evaluation. 14% of adult and 2% of pediatric nephrologists have not referred any patient to genetic evaluation, and 20% of adult and 5% of pediatric nephrologists reported that they have never returned genetic results.

Table 1:

participants’ characteristics

| Adult | Pediatric | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % of adults nephrologists | N | % of pediatric nephrologists | |||

| Total | 116 | 85 | 201 | |||

| Gender | Males | 80 | 69% | 37 | 44% | 117 |

| Females | 36 | 31% | 44 | 52% | 80 | |

| Non-binary | 0 | 0% | 2 | 2% | 2 | |

| Prefer not to answer gender question | 0 | 0% | 2 | 2% | 2 | |

| Race and ethnicity | White not Latino | 58 | 50% | 49 | 56% | 107 |

| Asian not Latino | 40 | 34% | 24 | 28% | 64 | |

| Black Not Latino | 1 | 1% | 4 | 5% | 5 | |

| Hawaii Not Latino | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 1 | |

| Native American Not Latino | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1% | 1 | |

| Multi-race not Latino | 0 | 0% | 3 | 4% | 3 | |

| Unknown, preferred not to answer, not Latino | 9 | 8% | 2 | 2% | 11 | |

| Latino | 7 | 6% | 2 | 2% | 9 | |

| Degree | MD | 68 | 59% | 42 | 49% | 110 |

| MD and other degree (PhD, MS, MPH, other) | 35 | 30% | 30 | 35% | 65 | |

| DO | 7 | 6% | 1 | 1% | 8 | |

| DO and other degree (PhD, MS, MPH, other) | 1 | 1% | 4 | 5% | 5 | |

| MBBS | 5 | 4% | 6 | 7% | 11 | |

| MBBS and other degree (PhD, MS, MPH, other) | 0 | 0% | 2 | 2% | 2 | |

| Clinical Setting | University-affiliated hospital | 71 | 61% | 64 | 75% | 135 |

| Other hospitals | 5 | 4% | 5 | 6% | 10 | |

| Solo or small practice with hospital affiliation | 21 | 18% | 11 | 13% | 32 | |

| No hospital affiliation | 15 | 13% | 4 | 5% | 19 | |

| Other | 4 | 3% | 1 | 1% | 5 | |

| Years since graduation from medical school | ≤5 years | 2 | 2% | 5 | 6% | 7 |

| 6–15 years | 31 | 27% | 18 | 21% | 49 | |

| 16–25 years | 45 | 39% | 30 | 35% | 75 | |

| ≥25 years | 38 | 33% | 32 | 38% | 70 | |

| Years of Nephrology practice | ≤5 years | 12 | 10% | 13 | 15% | 25 |

| 6–15 years | 45 | 39% | 30 | 35% | 75 | |

| 16–25 years | 28 | 24% | 18 | 21% | 46 | |

| ≥25 years | 31 | 27% | 24 | 28% | 55 | |

| Number of patients previously referred to genetic evaluation | None | 16 | 14% | 2 | 2% | 16 |

| 1–4 patients | 50 | 43% | 8 | 9% | 58 | |

| 5–9 patients | 15 | 13% | 14 | 16% | 29 | |

| 10–19 patients | 20 | 17% | 9 | 11% | 29 | |

| ≥20 patients | 15 | 13% | 52 | 61% | 67 | |

| Experience returning Genetic results | None | 23 | 20% | 4 | 5% | 27 |

| Limited (1–9 patients) | 68 | 59% | 22 | 26% | 90 | |

| Medium (10–25 patients) | 14 | 12% | 30 | 35% | 44 | |

| High (>25 patients) | 11 | 9% | 29 | 34% | 40 | |

Nephrologists’ confidence in utilizing genetic testing.

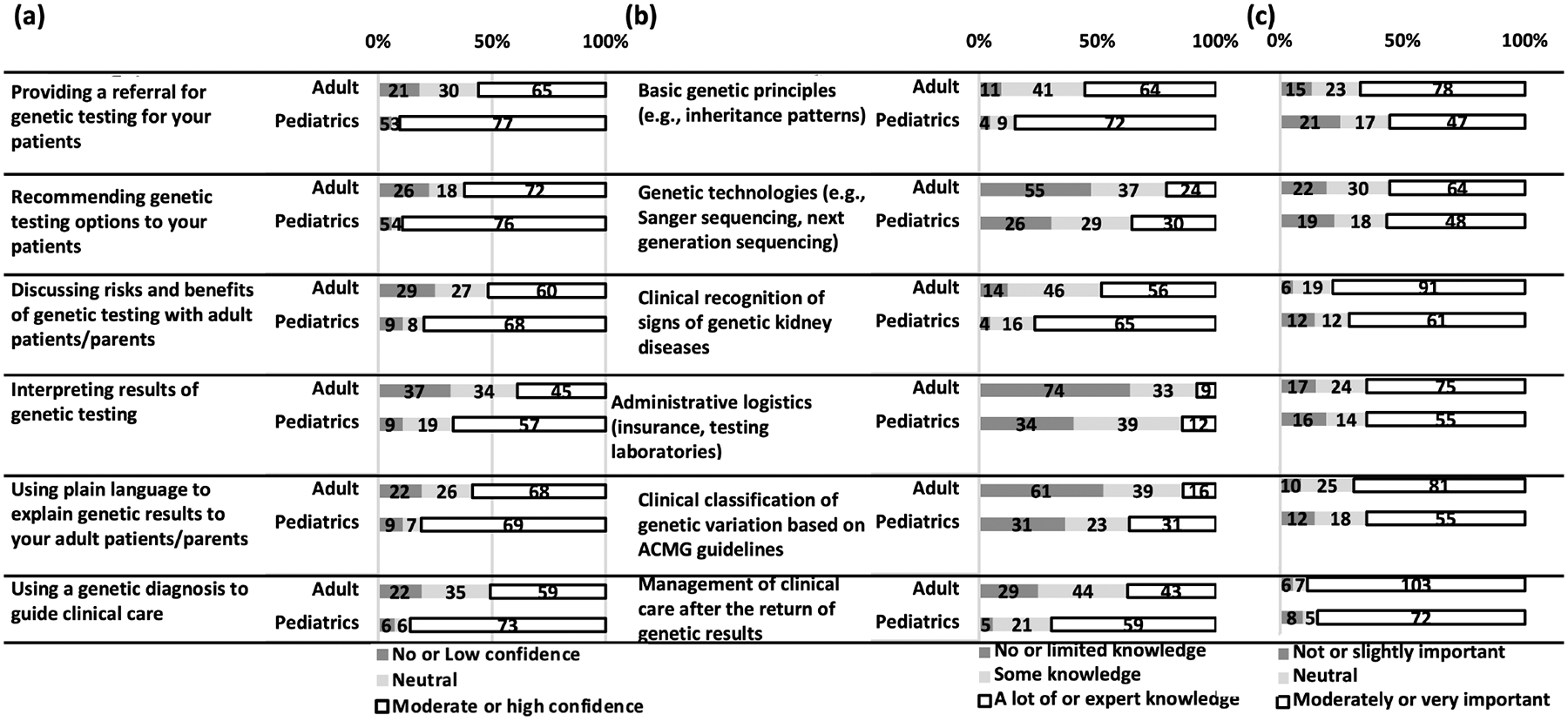

In 5 of the 6 domains examined, a majority of adult and pediatric nephrologists reported moderate or high confidence (Figure 1a), but only 38% of nephrologists reported moderate or high confidence in all 6 domains examined (n=76). About half of the adult and most pediatric nephrologists reported moderate or high confidence in (1) providing referral to genetic testing (56% and 91%, respectively); (2) recommending genetic testing to their patients (62% and 89%, respectively); (3) discussing risks and benefits of genetic testing (52% and 80%, respectively); (4) explaining genetic results (59% and 81%, respectively); and (5) using genetic results to guide clinical care (51% and 86%, respectively). Only 39% of adult nephrologists and a small majority of pediatric nephrologists (62%) reported “moderate or high confidence” in interpreting genetic results.

Figure 1: Nephrologists confidence in genetics, self-reported knowledge, and importance of knowledge improvement.

A. Nephrologists were asked how confident they are about 6 knowledge domains. Proportion of those with moderate or high confidence are presented in white, no opinion (neutral) in light grey, and no or low confidence in dark grey. B. Nephrologists were asked to rank their knowledge in 6 areas. Proportion of those with a lot or expert knowledge are presented in white, some knowledge in light grey, and no or limited knowledge in dark grey. C. Nephrologists were asked how important it is for them to improve their knowledge in the same 6 areas. Proportion of those reporting that it is moderately or very important are presented in white, no opinion (neutral) in light grey, and those reporting that such improvement was not or slightly important in dark grey. The number of nephrologists is in the bars, and the length of the bar represents the proportions of nephrologists.

Nephrologists self-rated knowledge in genetics and referral to genetic evaluation.

The proportion of adult and pediatric nephrologists self-rating their genetic knowledge as “a lot or expert knowledge” varied in the 6 knowledge domains (Figure 1b), and only 5% of nephrologists (n=11) reported “a lot or expert knowledge” in all 6 knowledge domains. A response of “a lot or expert knowledge” was reported regarding (1) basic genetic principles, in 55% of adult and 85% of pediatric nephrologists; (2) genetic technologies, in 21% and 35%, respectively; (3) clinical recognition of signs of genetic kidney diseases, in 48% and 76%, respectively; (4) administrative logistics, in 8% and 14%, respectively; (5) clinical classification of genetic variation based on guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), in 14% and 36%, respectively; and (6) management of clinical care after the return of genetic results, in 37% and 69%, respectively. Nephrologists who rated their knowledge in recognition of signs of genetic kidney diseases as “a lot or expert” were significantly more likely to have referred more patients to genetic evaluation (p-values<0.001, Table 2).

Table 2:

Association between genetic education, professional development, and referral of patients to genetic testing

| Specialization | Number of patients referred | Total | None | 1–4 | 5–9 | 10–19 | >20 | Wilcoxon rank sum test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical recognition of signs of genetic kidney diseases | Adult nephrology | A lot or expert knowledge | 56 (48%) | 1 (2%) | 18 (32%) | 7 (13%) | 17 (30%) | 13 (23%) | 1.07×10−16 |

| No or some knowledge | 60 (52%) | 15 (25%) | 32 (53%) | 8 (13%) | 3 (5%) | 2 (3%) | |||

| Pediatric nephrology | A lot or expert knowledge | 65 (76%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (8%) | 10 (15%) | 6 (9%) | 44 (68%) | 3.62×10−26 | |

| No or some knowledge | 20 (24%) | 2 (10%) | 3 (15%) | 4 (20%) | 3 (15%) | 8 (40%) | |||

| Genetic knowledge | Adult nephrology | Other | 77 (66%) | 10 (13%) | 31 (40%) | 11 (14%) | 14 (18%) | 11 (14%) | 2.01×10−12 |

| Lowa | 39 (34%) | 6 (15%) | 19 (49%) | 4 (10%) | 6 (15%) | 4 (10%) | |||

| Pediatric nephrology | Other | 57 (67%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 11 (19%) | 8 (14%) | 36 (63%) | 3.12×10−26 | |

| Lowa | 28 (33%) | 2 (7%) | 6 (21%) | 3 (11%) | 1 (4%) | 16 (57%) | |||

| Genetic Education during medical school | Adult nephrology | Neutral or sufficient | 70 (60%) | 9 (13%) | 35 (50%) | 6 (9%) | 12 (17%) | 8 (11%) | 9.9×10−14 |

| Somewhat insufficient or insufficient | 46 (40%) | 7 (15%) | 15 (33%) | 9 (20%) | 8 (17%) | 7 (15%) | |||

| Pediatric nephrology | Neutral or sufficient | 50 (59%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (10%) | 8 (16%) | 6 (12%) | 31 (62%) | 1.9×10−26 | |

| Somewhat insufficient or insufficient | 35 (41%) | 2 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 6 (17%) | 3 (9%) | 21 (60%) | |||

| Genetic Education during residency | Adult nephrology | Neutral or sufficient | 40 (34%) | 2 (5%) | 20 (50%) | 3 (8%) | 9 (23%) | 6 (15%) | 8.6×10−21 |

| Somewhat insufficient or insufficient | 76 (65%) | 14 (18%) | 30 (39%) | 12 (16%) | 11 (14%) | 9 (12%) | |||

| Pediatric nephrology | Neutral or sufficient | 47 (55%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6%) | 9 (19%) | 5 (11%) | 30 64%) | 1.3×10−26 | |

| Somewhat insufficient or insufficient | 38 (45%) | 2 (5%) | 5 (13%) | 5 (13%) | 4 (11%) | 22 (58%) | |||

| Genetic Education during the fellowship | Adult nephrology | Neutral or sufficient | 56 (48%) | 4 (7%) | 28 (50%) | 6 (11%) | 12 (21%) | 6 (11%) | 1.1×10−16 |

| Somewhat insufficient or insufficient | 60 (52%) | 12 (20%) | 22 (37%) | 9 (15%) | 8 (13%) | 9 (15%) | |||

| Pediatric nephrology | Neutral or sufficient | 65 (76%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (11%) | 11 (17%) | 7 (11%) | 40 (62%) | 3.6×10−26 | |

| Somewhat insufficient or insufficient | 20 (24%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (15%) | 2 (10%) | 12 (60%) | |||

| Genetic Education as a practicing physician through CME courses or seminars | Adult nephrology | Neutral or sufficient | 71 (61%) | 4 (6%) | 33 (46%) | 10 (14%) | 17 (24%) | 7 (10%) | 1.5×10−13 |

| Somewhat insufficient or insufficient | 45 (39%) | 12 (27%) | 17 (38%) | 5 (11%) | 3 (7%) | 8 (18%) | |||

| Pediatric nephrology | Neutral or sufficient | 69 (81%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (9%) | 12 (17%) | 6 (9%) | 45 (65%) | 3.2×10−26 | |

| Somewhat insufficient or insufficient | 16 (19%) | 2 (13%) | 2 (13%) | 2 (13%) | 3 (19%) | 7 (44%) |

Low knowledge: individuals who did not know at least one of the 6 basic concepts tested (Table S2)

Genetic literacy and basic genetic concepts understanding and referral to genetic evaluation.

The GeneLiFT scores ranged between 20 and 46, with a median of 43 (Figure S1). While most nephrologists recognized all real words tested using GeneLiFT (74%, n=149), only 13% of all participants (n=27) did not also flag a non-word. A minority recognized the term “actionability” as a real word (25% of adult and 35% of pediatric nephrologists, Table S1). More than a third (37%, n=72) did not recognize the word “autosome”. Similarly, the words “exome”, “exon”, “preventative” and “pathogenicity” were not recognized by up to 21% of the nephrologists (n=42). Regarding the 6 questions used to test nephrologists’ knowledge in genetics, 21% did not understand the concept of genetic risk (n=42), 15% the concept of panels or exomes (n=31) and 10% the concept of pharmacogenomics (n=21, Table S2). Overall, 33% of the nephrologists did not know at least one of the 6 basic concepts tested (39 adult nephrologists and 28 pediatric nephrologists) and were identified as having low genetic knowledge. A significant correlation was observed between low knowledge and lower referral of patients to genetic evaluation (p-value<0.001, Table 2)

Rating of past genetic education and referral to genetic evaluation.

More than a third of the nephrologists (40 %) reported somewhat insufficient or insufficient genetic education during medical school (Table S3). We observed significant differences in appraisal of genetic education between adult and pediatric nephrologists during residency, fellowship, and as practicing physicians. Most adult nephrologists reported insufficient genetic education during their residency and fellowship (65% and 52%, respectively). Adult nephrologists who graduated less than 25 years ago were less likely to report insufficient genetic education in medical school than those who graduated more than 25 years ago (p-value<0.001, Table S4, Figure S2). No significant difference on this issue was observed among pediatric nephrologists. Overall, nephrologists who reported sufficient genetic education during medical school, residency, fellowship, and clinical practice were significantly more likely to have referred more patients to genetic evaluation (p-values<0.001, Table 2). Most adult nephrologists who reported insufficient education during residency or fellowship (57%) have referred less than 5 patients to genetic evaluation.

Awareness of the legal protection given by GINA against genetic discrimination and referral to genetic testing.

Many nephrologists did not know that it is illegal for health insurance companies to use genetic information to determine health insurance eligibility, premium, or coverage (45% of adult and 33% of pediatric nephrologists). Concurrently, most nephrologists identified the risk of denial of eligibility for health, life, or disability insurance as factors that would discourage them from referring patients to genetic testing (Table 3).

Table 3:

Concerns regarding insurance eligibility as a barrier to referral to genetic testing

| To what extent would each of the following factors discourage you from referring a patient for genetic testing? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Prop | |||

| Genetic results may lead to denial of health insurance due to pre-existing conditions. | Adult | Strongly or somewhat discourage | 102 | 88% |

| Not discourage | 14 | 12% | ||

| Pediatric | Strongly or somewhat discourage | 70 | 82% | |

| Not discourage | 15 | 18% | ||

| Genetic results may lead to denial of eligibility for life insurance. | Adult | Strongly or somewhat discourage | 111 | 96% |

| Not discourage | 5 | 4% | ||

| Pediatric | Strongly or somewhat discourage | 73 | 86% | |

| Not discourage | 12 | 14% | ||

| Genetic results may lead to denial of eligibility for disability insurance. | Adult | Strongly or somewhat discourage | 108 | 93% |

| Not discourage | 8 | 7% | ||

| Pediatric | Strongly or somewhat discourage | 71 | 84% | |

| Not discourage | 14 | 16% | ||

Nephrologists’ interest in improving their genetic knowledge.

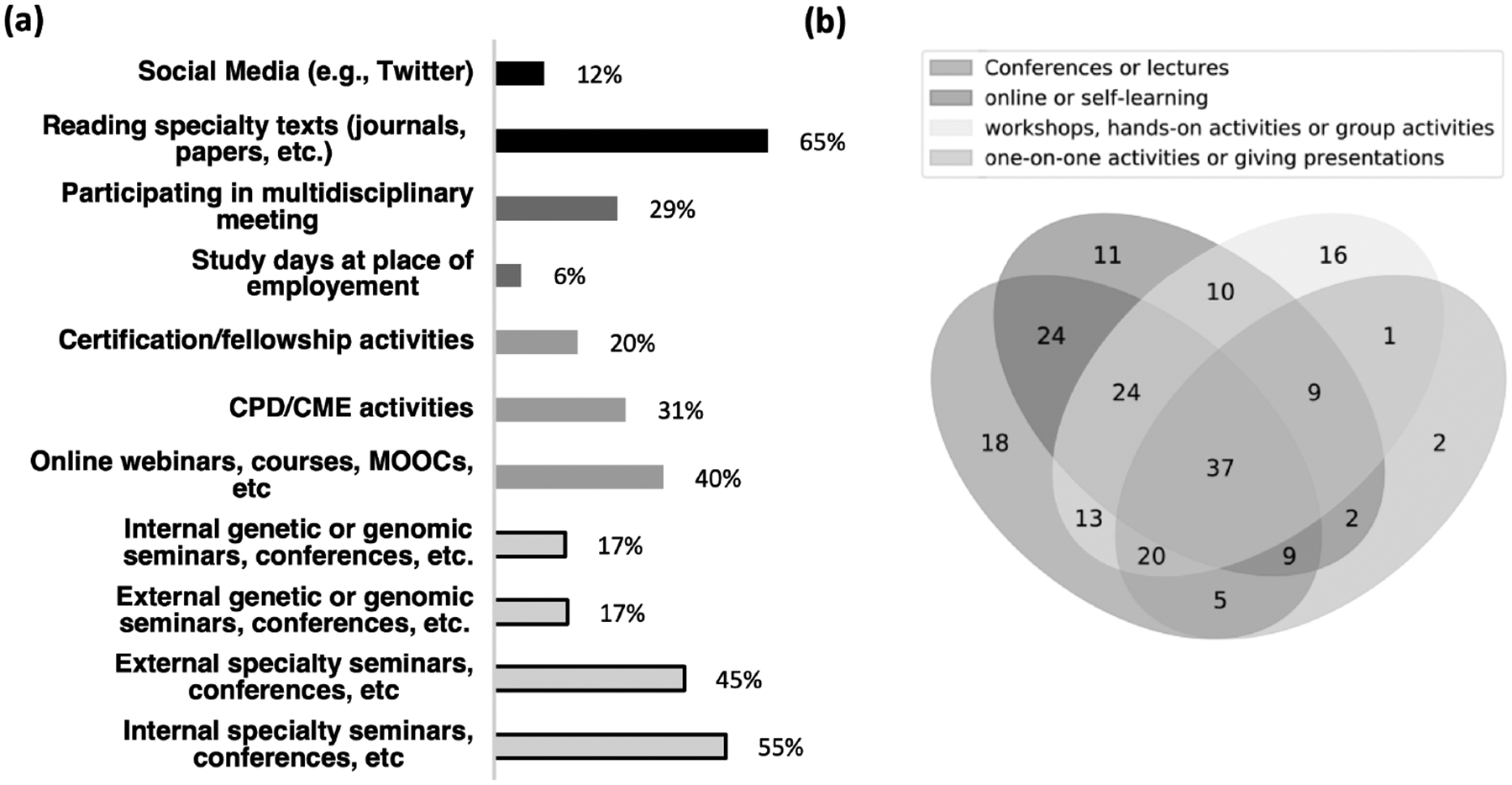

Most nephrologists (55–89%) reported that improving their knowledge in all 6 examined domains was moderately or very important (Figure 1c). This interest was not associated with the nephrologists’ practice setting. To keep abreast of, or learn new skills in, genomic medicine, most reported attending conferences and seminars, both internal and external to their institutions (n=151, 75%), courses including certification/fellowship, continuous medical education (CPD/CME), online webinars, massive open online courses (MOOCs), study days at place of employment (n=129, 64%), and reading papers (n=131, 65%, Figure 2a). When asked about the educational approaches that they find most effective, most nephrologists reported conferences or lectures as their preferred method for professional development (n=150, 75%), followed by workshops, hands-on activities or group activities (n=130, 65%), online or self-learning (n=126, 63%), and one-on-one discussion/reflection or preparing and giving a presentation/poster/paper/etc. (n=85, 42%), though most identified multiple complementary approaches (Figure 2b).

Figure 2: Most nephrologists would prefer to use multiple continued education methods.

(a) Methods nephrologists selected as currently accessed to keep up to date with, or learn new skills in, genomic medicine (survey question: Which of the following do you currently access to keep up to date with, or learn new skills in, genomic medicine? (Select all that apply.)). (b) Educational approaches nephrologists find most effective (survey question: Which professional development method/s do you find are most effective for you? (Select all that apply.)). Methods were grouped into 4 categories, and individuals who selected multiple categories are in overlapping areas.

Discussion

Genetic diagnosis holds promise for improving patient clinical care and management, and utilization of genetic testing has been increasingly supported by leading medical associations.24–26 However, maximizing the utilization of genetic testing in clinical settings depends on clinicians’ uptake of genomic medicine, level of genetic knowledge, and confidence in applying this knowledge in clinical settings. Despite professional guidelines, statements, and recommendations of genetic societies and associations, one of the major barriers to genetic testing is lack of referral of patients to genetic evaluation and testing.5 While genetic testing expanded to emerging fields of adult medicine, most studies that assessed genetic knowledge focused on oncologists,5 though this question is relevant also for other healthcare professionals. Our study is the first one to assess genetic knowledge of U.S. nephrologists and the association between rating of genetic education and referral of patients to genetic evaluation. Our findings regarding this medical specialty can shed light on key barriers to a genetic diagnosis for patients with kidney diseases.

Although most nephrologists reported having referred at least a few patients to genetic evaluation, we found that insufficient genetic education is associated with lower referral of patients to genetic evaluations. Nephrologists reported insufficient genetic education at all stages of their educational path and expressed a strong interest in enhancing their genetic knowledge.

A non-negligeable proportion of adult and pediatric nephrologists responded incorrectly to the 6 knowledge questions, consistent with previous reports on limited understanding of general genetic concepts by nurses and physicians in secondary and tertiary care.5 Although nephrologists had a better understanding of the concepts heritability, inheritance and penetrance than a cohort of research participants from the general public, a higher proportion of nephrologists responded incorrectly to the question on genetic risk compared to lay individuals.23 In line with a study pointing to the range of possible interpretations of the term actionable,27 most nephrologists and research participants from the general public did not recognize actionability as a real word.23 Preventative is another term that only about a fifth of the nephrologists and research participants from the general public did not recognize as a real word, despite its broad utilization in genomic and preventative medicine.23,28–30 These findings are significant as genetic testing often includes options for return of actionable results associated with preventative measures and nephrologists are increasingly expected to explain such options to their patients.31

Overall, U.S. nephrologists expressed higher confidence in genetics than a recently surveyed cohort of primary care physicians32 and Australian nephrologists.16 Most nephrologists reported high confidence in recommending genetic testing, which may reflect the impact of newly available large genetic panels encompassing most known genes that are associated with kidney diseases.33,34 These panels may allow nephrologists to offer the same test to most of their patients, easing administrational burden without requiring knowledge of specific gene-disease associations. However, clinical presentation affects interpretation of laboratory results.35 A meaningful discussion between the treating nephrologist and genetic specialists is central to ensure that the genetic test results are accurate and clinically relevant to the patient, especially as nephrologists’ limited knowledge may have harmful consequences on genetic results interpretation.

Many nephrologists, especially adult nephrologists, reported limited knowledge in identifying signs of underlying genetic causes of kidney disease, and these nephrologists were less likely to have referred patients to genetic evaluation. While differences in genetic knowledge between adults and pediatric nephrologists may be explained by higher prevalence of genetic renal diseases in pediatric patients and increased exposure during residency and fellowship training, the implications are significant. Referral to a genetic specialist can benefit patients without, but especially those with, classical signs for genetic renal diseases (i.e., early onset, positive family history, extra-renal manifestations, and unusual clinical presentation). Measures such as rotations of adult nephrology fellows in genetic clinics or pediatric nephrology may increase knowledge and confidence in the recognition of genetic disorders.

Additionally, most nephrologists reported limited knowledge of the ACMG guidelines for variant classification, the new genetic technologies, and the administrative logistics of ordering genetic testing—a particularly complicated educational topic given nephrologists’ diverse work settings. While referral to genetic counselors can alleviate clinicians’ burden, it is significant that most nephrologists indicated that expanding their knowledge is important. Expanding the educational opportunities for nephrologists is thus key. As the KDIGO paper19 emphasizes, identifying clinical signs of genetic kidney diseases is a skill that should be taught in foundational and continuing medical education courses, tested in certification and recertification exams, and included in corresponding reference materials.

Many nephrologists reported insufficient genetic education during residency and fellowship, especially adult nephrologists. Although more recent graduates reported better exposure to genetic education, there is still a need for expanding genetics modules in medical schools’ curricula36, during pediatric and internal medicine residencies37, and nephrology fellowships15, as well as through continuous medical education. The association between lower ratings of genetic education and lower referral to genetic evaluation suggests that improved genetic education could lead to improved utilization of genetic testing in nephrology. Most nephrologists reported reading specialty texts to develop their knowledge, highlighting the role of specialty journals in providing continuous genetic education. Only a minority reported joining structured educational activities such as certifications, CME, or MOOCs. Structural changes could improve access and incentivize nephrologists to engage with formal education opportunities to increase mastery of the core genetic competencies identified by the APHMG and KDIGO, such as inclusions of genetic related questions to re-certifications and creation of a sub-specialty in nephrogenetics.19 As most nephrologists preferred multimodal learning methodologies, it is also important to offer diverse opportunities for continuous education. Future research can develop genetic education material in various formats and test their acceptability and usability among nephrology fellows and clinicians.

Gaps in knowledge of GINA may negatively impact the implementation of genetic medicine. Studies of clinicians and the general public reported that concerns about genetic-based discrimination is a barrier to the utilization of genetic testing.5,21,22 Likewise, a high proportion of nephrologists indicated that concerns regarding insurance eligibility is a discouraging factor for referral of patients to genetic testing. An educational campaign can help remedy the significant gaps in nephrologists’ knowledge of GINA’s protections regarding health insurance. However, the absence of protection against life and disability insurance discrimination is likely to remain a challenge for the implementation of genetic medicine. While patients with kidney diseases in the U.S. may already experience the effect of their diseases on their eligibility (or premium) for insurance, the challenge is especially relevant for nephrologists recommending testing of potential donors or cascade testing of family members without a diagnosis. Such healthy individuals considering genetic testing are at risk of losing eligibility for life and disability insurance following a positive genetic testing. Nephrologists will thus need to be well-educated on GINA to inform patients, family members and potential donors about the legal limitations in protection as part of the pre-test counseling, with the hope that the issue will soon be rectified by changes in the U.S. law.

Limitations.

The highly educated sample of nephrologists in this study (a third had advanced degrees, a few had a DO and MBBS) may not be fully representative of the nephrologists practicing in the U.S. (The US Adult Nephrology Workforce 2016 Developments and Trends and the 2019 Nephrology Fellow Survey Results and Insights).38,39 The sample also comprised a high proportion of non-Hispanic/Latino White participants, and a high proportion of nephrologists working in academic settings. The survey only tested nephrologists’ basic genetic knowledge and their self-perceived knowledge and confidence, but did not cover all the competencies delineated by the recent KDIGO report or the APHMG.19,40 Moreover, while this article focused on clinicians’ education as a barrier to genetic testing utilization, many other barriers exist at the patient, clinician and the healthcare system levels. These barriers can be explored in future research. However, our findings inform about barriers for utilization of genetic testing in a large medical specialty, which could be relevant for other medical arenas as well. Our results provide a baseline for future research on the genetic competencies of clinicians and indicate the strong association between education and referral of patients to genetic evaluation.

CONCLUSION

A significant proportion of both pediatric and adult nephrologists have limited knowledge of the genetics of kidney diseases, posing a significant barrier to the uptake of genetic testing in nephrology. Although our survey focused on the subspeciality of nephrology, it is plausible that similar challenges exist in other medical arenas and subspecialities, impeding the successful implementation of genomic medicine. To begin addressing these challenges, there is a need to improve genetic education at all stages of clinical education, from medical school, to internships, fellowships and as part of continuous medical education. Further studies are needed to assess the impact of different educational methodologies on the utilization of genetic testing in clinical settings such as nephrology and to identify subspecialty-specific genetic needs and best approaches to increase genetic knowledge and uptake among clinicians.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Distribution of the GeneLiFT score in 195 nephrologists.

Six nephrologists were removed as they apparently skipped the test as they flagged less than 10 words and non-words.

Supplementary Figure 2: Nephrologists rating of their genetic education in medical school, residency, fellowship, and as practicing physicians. Analysis separated between pediatric and adult nephrologists, and those who graduated 6–15 years ago, 16–25 years ago or more than 25 years ago. The number of nephrologists is in the bars and the bars’ length represent the proportion of participants who responded: “insufficient or somewhat insufficient” (in blue), and “neutral, somewhat sufficient or sufficient” (in orange).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIDDK grants 3U01DK100876-08S1 and U01DK100876. We would like to thank the nephrologists who responded to the survey, and the CureGlomerulopathy (CureGN) Network, the National Kidney Foundation (NKF), the Alport Syndrome Association (ASF), and the American Society of Pediatric Nephrologists (ASPN) who helped spreading the invitations to the surveys.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Milo Rasouly received an innovation award from Natera, a private company selling genetic testing for kidney diseases.

Dr Ali Gharavi has Research Grants from Natera, Renal Research Institute. He is on the advisory board of Actio Biosciences, Astra Zeneca, Natera, Novartis, Travere and holds stock options of Actio Biosciences.

Maya Sabatello is an IRB member of the All of Us Research Program

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Ethics Declaration

We attest that the research included in this report was conducted in a manner consistent with the principles of research ethics, such as those described in the Belmont Report. This research was conducted with the voluntary, informed consent of any research participants, free of coercion or coercive circumstances, and received Columbia University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval consistent with the principles of research ethics and the legal requirements of the lead authors’ jurisdiction(s).

Informed consent was obtained from all participants as required by the IRB. All the data was de-identified.

Data Availability

Relevant survey questions and survey data will be made available upon request to the corresponding authors

References

- 1.Campion M, Goldgar C, Hopkin RJ, Prows CA, Dasgupta S. Genomic education for the next generation of health-care providers. Genet Med. 2019;21(11):2422–2430. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0548-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swink A, Nair A, Hoof P, et al. Barriers to the utilization of genetic testing and genetic counseling in patients with suspected hereditary breast and ovarian cancers. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32(3):340–344. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2019.1612702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curry M, Cruz R, Belter L, Schroth M, Lenz M, Jarecki J. Awareness screening and referral patterns among pediatricians in the United States related to early clinical features of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):236. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02692-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrow A, Chan P, Tucker KM, Taylor N. The design, implementation, and effectiveness of intervention strategies aimed at improving genetic referral practices: a systematic review of the literature. Genet Med. 2021;23(12):2239–2249. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01272-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White S, Jacobs C, Phillips J. Mainstreaming genetics and genomics: a systematic review of the barriers and facilitators for nurses and physicians in secondary and tertiary care. Genet Med. 2020;22(7):1149–1155. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0785-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman JM, Blitzer M, Elsas LJ, Francke U, Willard HE. Clinical objectives in medical genetics for undergraduate medical students. Genet Med. 1998;1(1):54–55. doi: 10.1097/00125817-199811000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasgupta S, Feldman GL, Powell CM, et al. Training the next generation of genomic medicine providers: trends in medical education and national assessment. Genet Med. 2020;22(10):1718–1722. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0855-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riegert-Johnson DL, Korf BR, Alford RL, et al. Outline of a medical genetics curriculum for internal medicine residency training programs. Genet Med. 2004;6(6):543–547. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000144561.77590.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groopman EE, Rasouly HM, Gharavi AG. Genomic medicine for kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:83–104. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groopman EE, Marasa M, Cameron-Christie S, et al. Diagnostic Utility of Exome Sequencing for Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(2):142–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lata S, Marasa M, Li Y, et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing in Adults With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Pilot Study. Annals of internal medicine. 2018;168:100–109. doi: 10.7326/M17-1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinto e Vairo F, Kemppainen JL, Lieske JC, Harris PC, Hogan MC. Establishing a nephrology genetic clinic. Kidney Int. 2021;100(2):254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas CP, Freese ME, Ounda A, et al. Initial experience from a renal genetics clinic demonstrates a distinct role in patient management. Genet Med. 2020;22(6):1025–1035. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0772-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundquist AL, Pelletier RC, Leonard CE, et al. From Theory to Reality: Establishing a Successful Kidney Genetics Clinic in the Outpatient Setting. Kidney360. 2020;1(10):1097–1104. doi: 10.34067/KID.0004262020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berns JS. A survey-based evaluation of self-perceived competency after nephrology fellowship training. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(3):490–496. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08461109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayasinghe K, Quinlan C, Mallett AJ, et al. Attitudes and Practices of Australian Nephrologists Toward Implementation of Clinical Genomics. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(2):272–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.10.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mrug M, Bloom MS, Seto C, et al. Genetic Testing for Chronic Kidney Diseases: Clinical Utility and Barriers Perceived by Nephrologists. Kidney Med. 2021;3(6):1050–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaikh A, Patel N, Nair D, Campbell KN. Current Paradigms and Emerging Opportunities in Nephrology Training. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27(4):291–296.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2020.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.KDIGO Conference Participants. Genetics in chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. Published online April 20, 2022:S0085-2538(22)00278-2. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong K, Weber B, FitzGerald G, et al. Life insurance and breast cancer risk assessment: Adverse selection, genetic testing decisions, and discrimination. Am J Med Genet. 2003;120A(3):359–364. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenartz A, Scherer AM, Uhlmann WR, Suter SM, Anderson Hartley C, Prince AER. The persistent lack of knowledge and misunderstanding of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) more than a decade after passage. Genet Med. 2021;23(12):2324–2334. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01268-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laedtke AL, O’Neill SM, Rubinstein WS, Vogel KJ. Family physicians’ awareness and knowledge of the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act (GINA). J Genet Couns. 2012;21(2):345–352. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9405-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milo Rasouly H, Cuneo N, Marasa M, et al. GeneLiFT: A novel test to facilitate rapid screening of genetic literacy in a diverse population undergoing genetic testing. J Genet Couns. Published online December 26, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone EM, Aldave AJ, Drack AV, et al. Recommendations for genetic testing of inherited eye diseases: report of the American Academy of Ophthalmology task force on genetic testing. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(11):2408–2410. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robson ME, Bradbury AR, Arun B, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement Update: Genetic and Genomic Testing for Cancer Susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3660–3667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musunuru K, Hershberger RE, Day SM, et al. Genetic Testing for Inherited Cardiovascular Diseases: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020;13(4):e000067. doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gornick MC, Ryan KA, Scherer AM, Scott Roberts J, De Vries RG, Uhlmann WR. Interpretations of the Term “Actionable” when Discussing Genetic Test Results: What you Mean Is Not What I Heard. J Genet Couns. 2019;28(2):334–342. doi: 10.1007/s10897-018-0289-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinlan C The Future of Paediatric Nephrology—Genomics and Personalised Precision Medicine. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2020;8(3):115–121. doi: 10.1007/s40124-020-00218-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lentine KL, Lam NN, Segev DL. Risks of Living Kidney Donation: Current State of Knowledge on Outcomes Important to Donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(4):597–608. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11220918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li PKT, Garcia-Garcia G, Lui SF, et al. Kidney Health for Everyone Everywhere – From Prevention to Detection and Equitable Access to Care. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51(4):255–262. doi: 10.1159/000506499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter JE, Irving SA, Biesecker LG, et al. A standardized, evidence-based protocol to assess clinical actionability of genetic disorders associated with genomic variation. Genet Med. 2016;18(12):1258–1268. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemke AA, Amendola LM, Kuchta K, et al. Primary Care Physician Experiences with Integrated Population-Scale Genetic Testing: A Mixed-Methods Assessment. J Pers Med. 2020;10(4):E165. doi: 10.3390/jpm10040165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller DT, Lee K, Chung WK, et al. ACMG SF v3.0 list for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing: a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. Published online May 20, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01172-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bean L, Funke B, Carlston CM, et al. Diagnostic gene sequencing panels: from design to report—a technical standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2020;22(3):453–461. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0666-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haspel RL, Genzen JR, Wagner J, Fong K, Undergraduate Training in Genomics (UTRIG) Working Group, Wilcox RL. Call for improvement in medical school training in genetics: results of a national survey. Genet Med. 2021;23(6):1151–1157. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01100-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen J, Lemons J, Crandell S, Northrup H. Efficacy of a medical genetics rotation during pediatric training. Genet Med. 2016;18(2):199–202. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMahon GM, Thomas L, Tucker JK, Lin J. Factors in career choice among US nephrologists. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(11):1786–1792. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03250312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Primack WA, Meyers KE, Kirkwood SJ, Ruch-Ross HS, Radabaugh CL, Greenbaum LA. The US Pediatric Nephrology Workforce: A Report Commissioned by the American Academy of Pediatrics. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2015;66(1):33–39. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Massingham LJ, Nuñez S, Bernstein JA, et al. 2022. Association of Professors of Human and Medical Genetics (APHMG) consensus–based update of the core competencies for undergraduate medical education in genetics and genomics. Genet Med. Published online August 2022:S1098360022008589. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Distribution of the GeneLiFT score in 195 nephrologists.

Six nephrologists were removed as they apparently skipped the test as they flagged less than 10 words and non-words.

Supplementary Figure 2: Nephrologists rating of their genetic education in medical school, residency, fellowship, and as practicing physicians. Analysis separated between pediatric and adult nephrologists, and those who graduated 6–15 years ago, 16–25 years ago or more than 25 years ago. The number of nephrologists is in the bars and the bars’ length represent the proportion of participants who responded: “insufficient or somewhat insufficient” (in blue), and “neutral, somewhat sufficient or sufficient” (in orange).

Data Availability Statement

Relevant survey questions and survey data will be made available upon request to the corresponding authors