Abstract

Cancer-related alterations of the p53 Tetramerization Domain (TD) abrogate wild-type (WT) p53 function. They result in a protein that preferentially forms monomers or dimers, which are also normal p53 states under basal cellular conditions. However, their physiological relevance is not well understood. We have established in vivo models for monomeric and dimeric p53 which model Li-Fraumeni Syndrome patients with germline p53 TD alterations. p53 monomers are inactive forms of the protein. Unexpectedly, p53 dimers conferred some tumor suppression that is not mediated by canonical WT p53 activities. p53 dimers upregulate the PPAR pathway. These activities are associated with lower prevalence of thymic lymphomas and increased CD8+ T-cell differentiation. Lymphomas derived from dimeric p53 mice show cooperating alterations in the PPAR pathway, further implicating a role for these activities in tumor suppression. Our data reveal novel functions for p53 dimers and support the exploration of PPAR agonists as therapies.

Introduction

As a stress-induced transcription factor with tumor suppressive activities, TP53 is the most frequently mutated gene in human cancer [1]. Activation of the p53 pathway results in outcomes that include apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, senescence, and altered metabolism. These responses are achieved through transcriptional regulation (up and down) of hundreds of genes [2, 3].

The stress-responsive unit of p53 is a tetramer. Four p53 monomers come together upon stress signaling through their tetramerization domain (TD) . Tetrameric p53 recognizes and binds to two sequential decameric motifs (or two half-sites) of DNA [4]. Tetramerization is essential for stabilization of the p53-DNA complex [5]. In vitro, p53 dimers are still able to bind DNA, although with 6-fold less efficiency, while monomers are 1000-fold less efficient than tetramers [5].

Monomers, dimers, and tetramers of p53 exist in cells. In resting states (basal), p53 is present mainly as dimers. In contrast, upon stress (such as DNA damage, hypoxia, oncogene activation), more than 90% of p53 is found as a tetramer [6, 7]. Although it is accepted that tetrameric p53 is required for full tumor suppressive activities, the physiological relevance of monomeric and dimeric states of p53 is not well understood.

Mutation of the p53 Tetramerization Domain (TD) is a mechanism by which cancers abrogate wild-type (WT) p53 function. Alterations in this region account for ~20% of mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), a cancer-predisposition disorder characterized by the presence of germline p53 mutations [8-10], and ~2% of somatic p53 alterations [10]. This implies a critical role for the tetramerization domain of p53 in tumor suppression [11]. Cancer-related mutations in the p53 TD often result in p53 proteins that preferentially form monomers, and to a lesser extent, dimers [10, 12]. Importantly, the oligomeric status of p53 TD mutants can impact clinical outcome in LFS patients. While individuals inheriting monomeric p53 TD mutants have a 100% cancer penetrance and a median survival time of ~33 years, multimeric p53 TD mutants exhibit a cancer penetrance of ~80% and 51 years median survival [13]. Additionally, patients with monomeric mutant p53 show shorter survival than patients with dimeric mutants, which is also shorter than patients with a TD mutant that causes a weak tetramerization defect [13]. This highlights the importance of the p53 TD in tumor suppression and the need to understand the mechanism of action of TD mutants in physiologically-relevant settings.

In vitro characterization of the effects that p53 TD mutations exert on p53 function have many caveats as non-physiological experimental conditions are known to impact p53 activity [14-18]. Mouse models of p53 TD mutations exist only for the most widely studied founder p53R337H (mouse p53R334H) mutant, prevalent in the Brazilian population. This mutation alters tetramerization to preferentially form monomers, but is permissive of tetramers under certain cellular conditions. Therefore, mice homozygous for p53R334H alleles have incomplete tumor penetrance [19, 20].

To gain a better understanding of the physiological activities of non-tetrameric p53 forms, we have established in vivo models for hot-spot p53 TD mutations, TP53R342P and TP53A347D (murine p53R339P and p53A344D), that result in monomeric and dimeric p53, respectively. These models phenocopy LFS patients with germline TP53 TD alterations. We found monomeric p53-bearing mice have similar phenotypes as p53-null mice, suggesting p53 monomers are inactive forms of the protein. Surprisingly, dimeric p53 bearing mice showed tumor suppressive features. However, p53 dimers are unable to execute canonical WT p53 activities. Instead, under basal conditions, p53 dimers upregulate a metabolic transcriptional program that is associated with PPAR activation. This pathway is altered in tumors, further implicating a role for these activities in tumor suppression. Single-cell RNA sequencing of basal thymus revealed that dimeric p53 mutant inhibits accumulation of CD8 single positive T-cells (CD8+) through upregulation of metabolic processes related to PPAR activation. Additionally, p53 dimer-bearing mice show systemic metabolic and anti-inflammatory phenotypes. This study comprehensively describes, for the first time, the consequences of complete abrogation of p53 tetramerization in vivo, and defines novel activities of p53 dimers in normal physiology. We propose these are “basal” activities in normal cells. Besides contributing to our understanding of p53 biology, this study sheds light on PPAR agonists as potential therapeutic agents.

Results

Generation of novel p53R339P and p53A344D knock-in mouse models

To understand the physiological activities of monomeric and dimeric forms of p53, we introduced R339P (denoted as RP) and A344D (denoted as AD) missense mutations into the p53 locus (human R342P and A347D, respectively). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene targeting was used to generate our models, schematically illustrated in Figure 1A. Founder animals were identified for both mutations (Supplementary Figure S1A) and were assayed for predicted off-target events (by PCR followed by sequencing of the top predicted off target sites – Supplementary Table S1). For elimination of potential other off-target events, mice were back-crossed twice to WT C57BL/6J mice. Approximately 700 bp of the p53 locus surrounding exon 10 was sequenced. Germline transmission was verified by PCR genotyping (Supplementary Figure S1B). Verification of oligomerization status of p53 proteins encoded by mutant alleles was carried out by chemical crosslinking (using glutaraldehyde) in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from mutant mice (Figure 1B). We confirmed the monomeric nature of p53RP and dimeric nature of p53AD. WT p53 and the DNA binding domain mutant p53R245W were used as positive tetrameric p53 controls (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure S1C). Crosses of heterozygous mutant mice yielded pups whose genotypes were consistent with Mendelian inheritance (Supplementary Figure S1D) and of normal body size (Supplementary Figure S1E).

Figure 1. A. Generation of p53RP and p53AD knock-in mouse models.

Mouse p53 exon 10 was independently targeted for Cas9 double strand breaks at the two desired sites (R339 in green, A344 in red) using two different sgRNAs. Donor DNAs contained desired alterations (green or red) and silent mutations (orange). B. Chemical crosslinking using glutaraldehyde (GA) in MEF lysates followed by western blot for p53. p53R245W/R245W MEFs were used as tetrameric p53 control (p53Ctrl). Monomers, ~53 KDa; dimers, ~100 KDa; tetramers, >180KDa. Survival curves for p53 mutant mice from LFS (C) or LOH (D) cohorts (**p=0.0064, ***p=0.0008, ****p<0.0001, ns= not significant). E. Prevalence of thymic lymphomas in p53 mutant mice (LOH cohort) at end point. F. Cellular composition of thymic lymphomas by genotype. CD3 (T-cells, left) and B220 (B-cells, right). p53−/− N=6, p53RP/− N=8, p53AD/− N=3. G. Thymic lymphoma weight by genotype measured as percentage of body weight (* p<0.05).

Dimeric p53 bearing mice display some tumor suppressive features

To determine the role of monomer and dimer mutants on tumor development, we generated several cohorts. To mimic LFS, we established cohorts of p53+/−, p53RP/+, p53AD/+, and p53+/+ (control) mice. To mimic a loss of heterozygosity (LOH) scenario, a common phenomenon in LFS-derived tumors [21], we established cohorts of p53-null, p53RP/− and p53AD/− mice (p53+/− as control). This cohort also allowed us to monitor mutant-specific outcomes. Additional homozygous (p53RP/RP and p53AD/AD) mutant cohorts were established to interrogate allele dose-dependency of phenotypes.

Mice harboring mutant p53 TD alleles were prone to spontaneous tumor development. p53RP/+ mice had a median survival of 416 days similar to p53+/− littermates at 420 days (Figure 1C). Unexpectedly, p53AD/+ mice lived significantly longer, with a median survival of 548 days, and two mice (8%) lived beyond the 2-year threshold and were tumor-free at end point (Figure 1C). However, survival of p53AD/+ mice was much shorter than WT p53 mice (85% of mice lived past 2 years). In our LOH cohort, p53RP/− mice had a similar life-span as p53-null mice, with median survival times of 142 and 140 days, respectively. On the other hand, p53AD/− mice lived significantly longer (median survival of 184 days) than p53-null mice, but they still had a significantly shorter lifespan than p53+/− mice (Figure 1D). Homozygous mutant mice (p53RP/RP and p53AD/AD) showed two p53AD alleles confer longer survival (median survival of 240 days, Supplementary Figure S2A) than mice with two p53RP alleles (median survival of 160 days).

p53RP/− and p53−/− mice succumbed mainly to thymic lymphomas (60-70%, TLs). Importantly, p53AD/− mice had lower incidence of TLs (~27%) (Figure 1E, Supplementary Figure S2B-C). Peripheral lymphomas (mesenteric and others) were seen in p53AD/− mice in slightly increased prevalence as compared to all other genotypes, possibly suggesting a role for p53 dimer activities in early lymphocyte development that is dispensable later on. All mice developed sarcomas at similar ratios (Supplementary Figure S2B). We analyzed the cellular composition, mitotic index, apoptosis, and tumor weight of thymic lymphomas at end point. All tumors analyzed were composed of T-cells (CD3 marker). In addition, some tumors had a B-cell component (B220 marker) that was most prevalent in p53−/− and p53RP/− thymic lymphomas analyzed as compared to p53AD/− (Figure 1F, Supplementary Figure S2D). However, we did not assess whether B-cells found within tumors are tumor cells. Lastly, tumor weight (measured as % of body weight) at end point was significantly lower in p53AD/− thymic lymphomas as compared to p53−/− (comparison to p53RP/− did not reach significance) (Figure 1G). In summary, the prolonged survival, decrease in thymic lymphoma incidence, and reduced tumor weight at end point suggested the p53AD mutant elicits tumor suppressive activities.

Dimeric p53-derived tumors require more genomic hits than monomeric-derived ones

Only 27% of p53AD/− mice develop thymic lymphomas, as compared to ~65% in p53-null and p53RP/− mice. This apparent tumor suppressive feature of p53AD led us to hypothesize that tumors that evolve with a p53AD mutation may accumulate additional cooperating alterations to overcome its tumor suppressive activities. We first assessed whether p53AD/− thymic lymphomas lose the p53AD allele. We were able to detect the retention of this allele in all 7 analyzed tumors (Supplementary Figure S3A). We then performed whole exome sequencing of p53RP/− and p53AD/− thymic lymphomas (N=7/group) at end point and analyzed for copy number alterations. We found that p53AD/− thymic lymphomas accumulated more alterations than p53RP/− lymphomas, and the main alterations were deletions (Supplementary Figure S3B). We utilized the publicly available TSGene database (https://bioinfo.uth.edu/TSGene/) of genes with reported tumor suppressive functions, and overlapped it with genes deleted in these lymphomas. 105 of p53AD/− thymic lymphomas-specific deleted genes were tumor suppressors (TSGs, p<2.983e−6), including the commonly known Pten and Rb1 TSGs. None of the p53RP/− tumors deleted peaks contained TSGs (Supplementary Figure S3C), although the number of deleted genes overall was much smaller than in p53AD/− tumors. By overlapping amplified genes with the ONGene Database [22] for human oncogenes, we found Mycn significantly amplified in p53AD/− tumors. We also found amplification of Ddx1, another reported oncogene not present in the database [23] (Supplementary Figure S3D). p53RP/− tumors did not amplify oncogenes (Supplementary Figure S3E).

To understand whether this was a general feature of p53AD/− -derived tumors, we also investigated the presence of cooperating genomic alterations in hemangiosarcomas derived from p53RP/− or p53AD/− mice. Similar to thymic lymphomas, in this tumor type we detected an increased number of genes altered in p53AD/− tumors as compared to p53RP/− ones (Supplementary Figure S3F). In this case, the most common alteration was amplification, which included amplification of 47 previously reported genes with oncogenic functions in p53AD/− tumors as compared to only one in p53RP/− tumors (Supplementary Figure S3G). In hemangiosarcomas, none of the deleted genes were TSGs regardless of genotype (Supplementary Figure S3H). Taken together, these data are consistent with the need to accumulate cooperating alterations to overcome the residual tumor suppression of p53AD (Supplementary Figure S3E, I).

p53AD does not retain canonical stress-induced activities

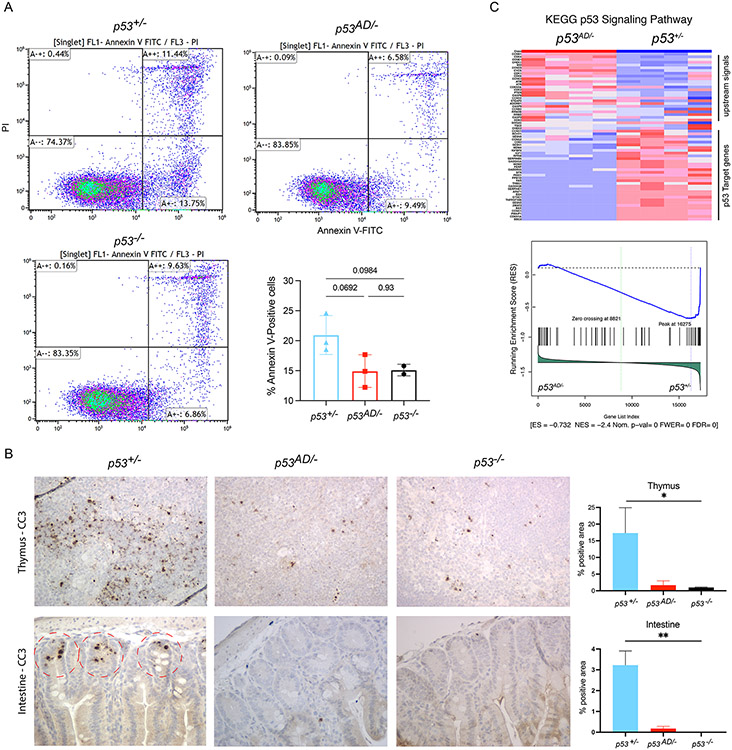

In order to understand whether p53AD promotes tumor suppression through retention of some WT p53 activities, we exposed p53−/−, p53AD/−, and p53+/−, and mice to sub-lethal doses of whole-body irradiation (IR, 6Gy) and assayed various tissues for apoptosis 4h later. In the thymus, IR induced stabilization and phosphorylation of p53TD mutants (Supplementary Figure S4A). p53AD remained dimeric upon IR in the thymus, while WT p53 formed tetramers (Supplementary Figure S4B). Thymus and intestine tissues derived from p53AD/− mice showed a phenotype comparable to p53-null samples in their inability to initiate apoptosis upon DNA damage (Figure 2A-B). We also assessed apoptosis levels in samples derived from irradiated homozygous mice, finding no differences between p53AD/AD and p53−/− (Supplementary Figure S4C). Additionally, RNA-sequencing showed that p53 dimers do not upregulate WT p53 targets in the thymus following DNA damage, as p53 signaling was the top downregulated pathway (normalized enrichment score of −2.4) in comparison to samples that contained WT p53 (Figure 2C). Furthermore, to validate this result was indeed due to failure to transactivate WT p53 target genes by p53AD, we analyzed expression levels (RNA-seq derived normalized read counts) for 10 canonical p53 target genes in p53+/−, p53AD/−, p53RP/− and p53−/− thymi upon IR. This analysis showed decreased expression of all ten p53 target genes in p53AD/−, p53RP/− and p53−/− thymi as compared to p53+/− (Supplementary Figure S4D). Moreover, we analyzed the enrichment of a gene set composed of previously published WT p53-bound and p53-regulated genes (denoted as Gene Set p53_bound_up_Kenzelmann Broz et al, extracted from Kenzelmann Broz et al [24]). Again, this set of genes was enriched in WT p53-bearing samples but not in p53AD/− ones (Supplementary Figure S5A). Nine of the ten genes shown in Figure S4D are also part of this list. Lastly, we sought to determine if p53AD is a true loss-of-function allele by a genetic approach. We asked whether p53AD alleles are able to rescue the p53-dependent apoptotic lethality associated with Mdm2 deletion [25]. p53AD/AD mutant mice were able to rescue p53-dependent embryo lethality caused by genetic deletion of Mdm2, suggesting p53AD is a loss of function allele (Supplementary Figure S5B). p53RP showed p53-null like phenotypes in all assays (Supplementary Figure S4D, S5B-C).

Figure 2. p53AD does not retain canonical stress-induced activities.

A. Flow cytometry for Annexin V-FITC and PI staining of thymocytes. Bar graph shows results summary. B. Cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) immunohistochemistry in thymus (top row) and intestine (bottom row) after IR. Representative figures are shown, taken at 40X magnification). Quantification plots on the right (N=2/group), *p<0.05 C. RNA sequencing of dimer (p53AD/−) and WT (p53+/−) post-IR thymus samples (N=4/group) shows downregulation of p53 signaling pathway in p53AD samples. Blue is downregulation, red is upregulation.

p53 dimers promote a novel transcriptional program

Because p53 dimers are the main oligomeric state of p53 in basal cellular conditions [6, 7], we hypothesized that the activities responsible for the phenotypes observed occur at basal states. The observation that p53AD was more stable in thymocytes (likely due to inability to transactivate Mdm2) provided an opportunity to study the contribution of p53 dimers to tumor suppression (Supplementary Figure S4A-B).

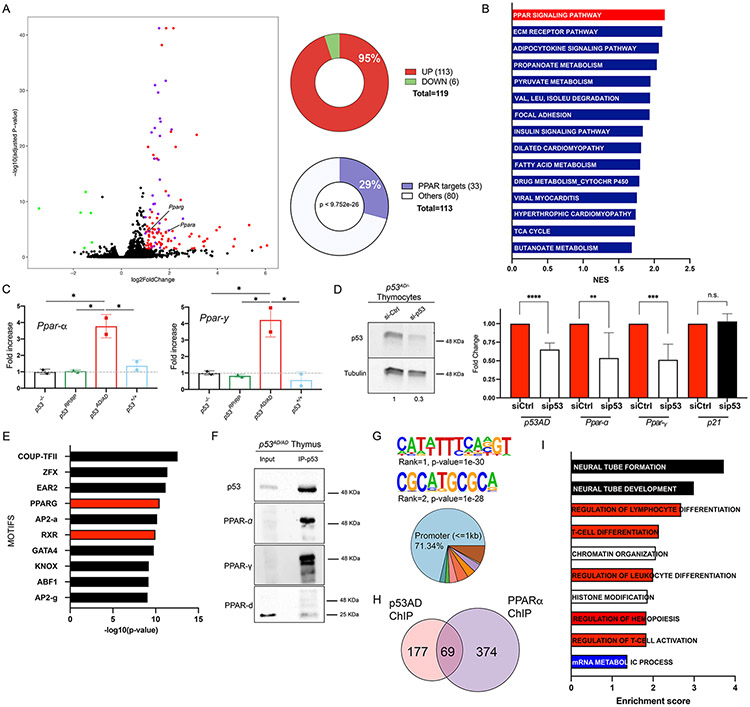

To this end, we performed RNA-sequencing in thymus samples from 4-week-old p53AD/− and p53−/− mice prior to tumor formation. We found 119 differentially expressed genes (DEGs, Log2 Fold Change cut-off of ∣1∣, FDR<0.05), most of them upregulated (95%, N=113) in p53AD/− as compared with p53−/− thymus (Figure 3A). Pathway analysis of DEGs revealed metabolic pathways were upregulated, with the PPAR signaling pathway at the top (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure S6A-B). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) suggested PPAR-α and PPAR-γ (and PPAR agonists Rosiglitazone and Troglitazone) as potential upstream regulators of this transcriptional program (Supplementary Figure S6C). Ppar-α and Ppar-γ transcripts themselves were also upregulated in p53AD/− thymi (Figure 3A). We validated the upregulation of Ppar-α and Ppar-γ transcripts in homozygous thymi samples, confirming that this is exclusive to p53AD-bearing samples (Figure 3C). WT p53-bearing samples showed a slight increase in Ppar-α that was not statistically significant. Lastly, we queried how many of the 113 dimeric p53-upregulated genes were also PPAR targets (PPARs are transcription factors [26]). We used a dataset of 448 high-confidence predicted PPAR target genes [27] and found a significant overlap (p < 9.752e−26), 33 of 113 upregulated genes (29%) being direct PPAR target genes (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table S2), supporting the prediction of PPAR-α and PPAR-γ as upstream regulators. To test the dependency of this transcriptional program on p53AD presence, we harvested primary thymocytes from p53AD/− mice, and treated them with a control siRNA or siRNA targeting p53. Upon p53AD knock-down to approximately 30%, we observed concomitant reduction of Ppar-α and Ppar-γ transcripts, but not that of Cdkn1a (p21), a canonical WT p53 target (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. p53AD upregulates the PPAR pathway.

A. Volcano plot of DEGs in p53 dimer (p53AD/−) vs p53-null thymi in basal conditions (FDR<0.05, Log2 fold change cut-off of ∣1∣). Green dots: down-regulated genes; red dots, upregulated genes; purple dots, upregulated genes that are PPAR targets (total 33). Right: percentage of upregulated DEGs (top pie chart), and percentage of upregulated DEGs that are direct PPAR targets (p<9.752e−26, bottom pie chart). B. Top 15 upregulated KEGG pathways in p53AD/− vs. p53-null thymi in basal conditions (FDR<0.05). NES is normalized enrichment score. C. qRT-PCR validation of Ppar-α and Ppar-γ upregulation in thymi from homozygous mutant mice (p53AD/4D, dimers) in basal conditions (N=2/genotype), *p<0.05. D. p53AD knockdown in primary thymocytes derived from p53AD/− mice. Left: Western Blot for p53 and tubulin (loading control, quantification of p53 levels below blot). Right: qRT-PCR of p53, Ppar-α, Ppar-γ, and p21 in control (siCtrl) and p53 knockdown (sip53) thymocytes (N=2 mice). **p=0.0077, ***p=0.0002, ***p<0.0001, n.s.= not significant. E. Top 10 transcription factor motifs enriched in differentially open regions from p53AD/− vs p53-null ATAC-seq data (N=3/group). F. p53 immunoprecipitation in p53AD/AD thymus, followed by western blot for p53, PPAR-α, PPAR-γ, and PPAR-δ. All blots were run separately. We used secondary antibodies that do not detect denatured heavy and light IgG chains. G. Top 2 de novo motifs predicted by HOMER for p53AD binding. Genomic regions of p53AD peaks (bottom). Dark blue is 1-2kb promoter (2.44%), green is 2-3kb promoter (1.83%), pink is first exon (3.66%), red is other exon (4.88%), orange is first intron (3.66%), purple is other intron (3.66%), beige is downstream (0.61%), brown is distal intergenic (7.93%). H. Venn diagram for number of genes bound by p53AD and/or PPAR-α by ChIP-seq experiments in basal p53AD/AD thymi. I. Gene ontologies of p53AD and PPAR-α bound genes. GOBP database was used. FDR<0.005.

We then asked whether sequences containing PPAR response elements were more accessible in p53AD-bearing samples as compared to p53-null ones. We performed ATAC-seq on basal thymi from p53AD/− and p53−/− mice (4-week old). We found the PPAR-γ and Retinoid X Receptor (RXR, forms part of the same transcriptional complex together with the PPAR proteins [28]) motifs were enriched in differentially open regions in p53AD-bearing samples (Figure 3E). We also found an enrichment of p53 half-sites (the DNA unit for p53 dimer binding) in these regions (enrichment ratio of 1.19, p-value=0.00000011). We additionally obtained a list of congruent genes that were differentially upregulated from RNA-seq (Figure 3A) and differentially open from ATAC-seq in p53AD/− as compared to p53−/− (both datasets were generated with different biological replicates, Supplementary Table S3). We did not see differences in accessibility at Ppar-α and Ppar-γ loci as both had clear open regions around gene promoters in all samples (Supplementary Figure S6D-E). However, our analysis did detect a significantly differential open region in p53AD/− samples at the Lncppar-α locus, ~30Kb upstream of Ppar-α (Supplementary Figure S6F). This is an understudied region; however, it is possible that it may contain an enhancer that influences Ppar-α expression.

These findings led us to ask whether p53 dimers form a complex with PPAR proteins to direct this transcriptional program. In p53AD/AD thymi, p53AD co-immunoprecipitated with PPAR-α and PPAR-γ but not PPAR-δ (Figure 3F). We confirmed p53AD-PPAR-α binding and lack of interaction with WT p53 in MEFs derived from p53AD/AD and p53WT mice (Supplementary Figure S7A). As shown above, WT p53 forms tetramers in MEFs, suggesting that p53 tetramers do not interact with PPAR-α (Supplementary Figure S1C).

In order to experimentally interrogate co-localization of p53AD and PPARs in regulatory regions of genes, we performed ChIP-sequencing for p53 or PPAR-α in p53AD/AD thymi (4 week- old, N=2). Consistent with our previous prediction of p53AD binding to p53 half-sites, de novo motif prediction by HOMER for p53AD binding sites identified a p53 half-site sequence, and a new binding motif of unknown significance (Figure 3G, top). Most of p53AD binding occurred at promoter regions (Figure 3G, bottom). We found 246 genes with significant peaks for p53AD binding and 443 for PPAR-α binding compared to input, with co-localization of p53AD and PPAR-α in promoters of 69 genes (28% of p53AD-bound genes) (Figure 3H). We explored the ontologies of these genes using the Gene Ontology Biological Process database and found significant overlap with several pathways, with lymphocyte differentiation and chromatin-related pathways as the most enriched (Figure 3I). These data support a model in which p53AD and PPAR-α cooperate to regulate a novel set of genes, and suggest that epigenetic changes and cell differentiation may contribute to the observed tumor suppression. Still, a significant number of genes were bound by p53AD alone (including Ppargc1b, is a co-activator of PPAR-γ; and Hadh, supports β-oxidation in the mitochondria), which suggests p53AD may also promote transcription on its own or in cooperation with other transcription factors, possibly PPAR-γ or CCNC (also a predicted upstream regulator, Supplementary Figure S6C, and part of the transcriptional regulator Mediator complex).

Four genes (Hadh, Fabp4, Glul, and Dab2ip) showed overlap between ChIP-seq data for p53AD or PPAR-α in p53AD/AD thymi and RNA-seq data from p53AD/− vs p53−/− thymi (Figure 3A). We looked for additional indications of potential p53AD-PPAR co-binding by searching for p53 half sites in the vicinity of PPAR response elements in regulatory regions of PPAR targets upregulated by p53AD from RNA-seq data (up to 10 kb sequences). We found 26 of 33 genes (78.78%) have p53 half-sites in variable proximity to their PPAR response elements (Supplementary Figure S7B, Supplementary Table S4). To rule out that these are sites commonly present in regulatory regions of all genes, we performed motif enrichment analysis (using SEA algorithm from MEME suite) of p53 half-sites in the 26 p53AD upregulated genes compared to 20 randomly selected genes (by a random gene set generator from molbiotools.com, using up to 10kb of their regulatory sequences, Supplementary Table S5). We found a 3.89 enrichment ratio of p53 half-sites in our set of 26 PPAR target genes (p=0.0649). These data suggest that these genes may also be regulated in the same manner by p53AD and PPARs. Overall, these data led us to propose that p53AD-dependent activation of PPAR pathway and related signaling may explain the p53AD tumor suppressive phenotype. Importantly, a role for PPARs in tumor suppression has been previously described [29-34], although it is context-specific [35, 36].

Lastly, we asked whether our findings of PPAR pathway upregulation can be extrapolated to WT p53 in basal states (previously reported as mainly dimeric [6, 7]), and to other cancer-relevant dimeric p53 mutants. We performed RNA-sequencing of p53+/− vs p53−/− thymi under basal conditions. Pathway analysis showed an upregulation of the PPAR pathway in WT p53-bearing samples (NES= 1.9, q-value= 0.0011), although this was not the top pathway (Supplementary Figure S7C). These findings suggest PPAR activation may be a feature of WT p53 dimers as well. To examine the functionality of other p53 dimers, we overexpressed human p53A347D (dimer), p53A347S (dimer), p53K351E (dimer), and p53A347P (monomer, control) [11] in HEK293T cells and analyzed expression levels of PPAR target genes. We found an increase in expression of three genes (upregulated in RNA-seq data in Figure 3A) PLIN4, ACACB, and PDK4 in all three dimeric p53 mutants as compared to the monomeric one (Supplementary Figure S7D). These results suggest activation of the PPAR pathway may be a feature of other dimeric forms of p53.

p53AD-derived thymic lymphomas alter the PPAR pathway

Since the PPAR pathway is upregulated in p53AD/− thymi, we hypothesized that thymic lymphomas derived from p53AD/− mice may need to disable this pathway to promote cell transformation. To test this hypothesis, we probed the levels of Ppar-α and Ppar-γ transcripts in thymic lymphomas vs normal thymi from p53AD/− mice. We found a significant decrease in Ppar-γ expression in tumors as compared to normal tissues (Supplementary Figure S7E). Additionally, we asked whether any of the previously discussed deleted genes in p53AD/− -derived thymic lymphomas were PPAR targets. We found a significant overlap between deleted genes and PPAR targets (p<1.709e−4), with 33 PPAR targets deleted in at least two tumors, and 11 of them deleted in 71% of cases (Supplementary Figure S7F, Supplementary Table S6). None of these PPAR target genes were deleted in p53RP/− thymic lymphomas. In addition to these data, the retinoic acid receptor beta (Rarβ), which participates in similar cellular processes as the PPARs [37], was also deleted in 71% of p53AD/− thymic lymphomas analyzed (but not in p53RP/− tumors) (Supplementary Figure S7F). Of note, the 2 tumors that did not show deletion of any PPAR targets show lower Ppar-γ expression, deletion of Pten, and amplification of Mycn. Previous studies have implicated a role for PPARs in activating PTEN [38]. Unlike thymic lymphomas, we did not find deletion of PPAR target genes (nor Pten) in any of the hemangiosarcomas analyzed regardless of genotype. These findings further support a tumor suppressive role for the PPAR pathway in thymic lymphomagenesis in the presence of p53AD.

p53AD inhibits CD8+ T-cell accumulation similar to WT p53 in the thymus

The thymus is a lymphocyte-training organ where cell development and differentiation occur in early life. Thus, we wanted to dissect the cellular processes impacted by p53AD that may suppress thymic lymphomagenesis. Given PPARs function in lipid metabolism, we first ruled out ferroptosis as a potential mechanism for p53AD-mediated reduction in thymic lymphoma incidence. We stained for a lipid peroxidation marker (4-Hydroxynonenal, 4-HNE) in irradiated thymocytes from p53+/+, p53AD/AD, and p53-null mice. Positive staining was seen for p53+/+ samples but not for p53AD/AD or p53-null ones (Supplementary Figure S8A), suggesting that p53AD does not induce ferroptosis in these cells.

Bone marrow-derived lymphoid progenitors seed the thymus where signals from the microenvironment promote T-cell lineage commitment, survival and maturation. CD4−CD8− double negative (DN) immature thymocytes that undergo successful TCRβ gene rearrangements initiate TCRα gene rearrangements and progress to the CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP) stage. Positively selected TCRαβ+ thymocytes downregulate either CD4 or CD8 and migrate into the medulla where central tolerance mechanisms induce apoptosis of self-reactive T-cells, or generate T-regulatory suppressor cells [39]. An arrest in any of these differentiation steps could cause cells to undergo erratic proliferation, possibly contributing to lymphomas formation as observed in our mouse models.

The PPAR proteins have been previously implicated in the regulation of energy metabolism and cell differentiation [40, 41]. T-cells lacking Ppar-α or -γ are hyper-responsive to TCR stimulation, promoting cytokine production and proliferation [42]. We hypothesized that p53 dimers are able to partially halt thymic lymphomagenesis through the upregulation of the PPAR signaling pathway by allowing for proper cell differentiation. Thus, we sought to understand differences in cell populations in p53 dimer (p53AD/−) vs p53-null thymi, and the transcriptional programs in different cell types, through single-cell RNA-sequencing.

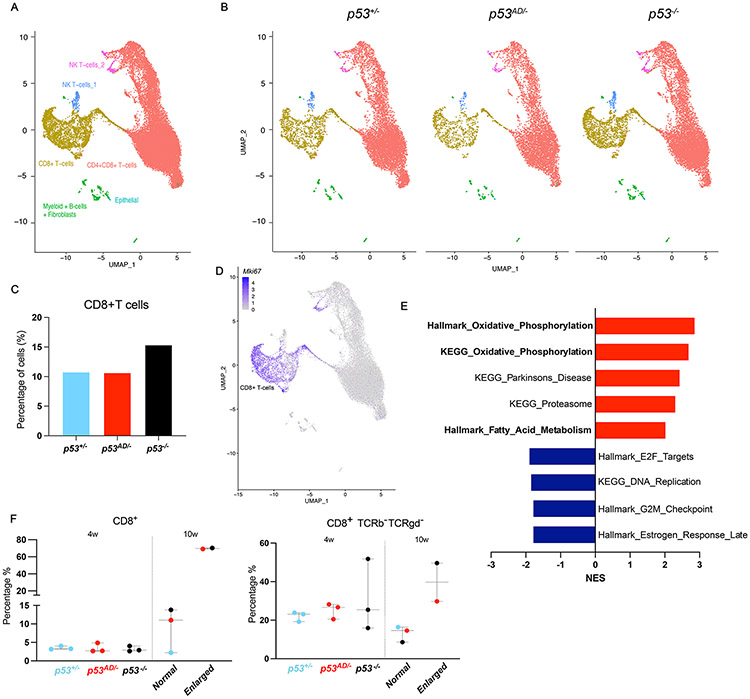

We sequenced RNA derived from single cell-dissociated thymi of p53+/−, p53AD/−, and p53-null mice (females at 1 month of age). We found higher abundance of CD8+ single positive T-cells in p53-null thymus than in p53AD/− or p53+/− samples (Figure 4A-C, Supplementary Figure S8B). Importantly, these CD8+ cells were actively proliferating, as defined by strong Mki67 expression (Figure 4D). These data suggest that p53 dimers inhibit proliferation and, therefore, accumulation of CD8+ T cells similar to WT p53. When comparing the transcriptomes of CD8+ T cells in p53AD/− vs p53-null datasets through GSEA, we found upregulation of classic PPAR signaling-related biological processes such as oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid metabolism, in addition to downregulation of proliferation-related pathways (DNA replication) (Figure 4E), in p53 dimer-bearing cells. Additionally, using IPA as another tool to dissect differential pathways, we found an upregulation of the PPAR signaling pathway (and the related VDR/RXR pathway) as well as other proliferation inhibitory pathways (PTEN pathway) (Supplementary Figure S8C), in p53 dimer-bearing cells as compared to cells lacking p53.

Figure 4. p53AD inhibits CD8+ T-cell accumulation similar to WT p53 in the thymus.

A. Single-cell RNA-sequencing of 4-week old thymi from p53+/−, p53AD/−, and p53−/− mice (N=1/genotype). Figure shows merged UMAP graph with labeled clusters. B. UMAP by genotype. C. Quantification of cells per genotype in the CD8+ T-cell cluster. D. Mki67 expression by cluster shows high expression in CD8+ T-cells. E. Upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) pathways in p53AD/− vs p53−/− CD8+ T-cells. p<0.05. F. Percentage of CD8+ (left) and CD8+ TCRb− TCRgd− (right) T-cells at 4 weeks (p53+/−, p53AD/−, and p53−/−, N=3) and 10 weeks (normal sized, N=3; or enlarged thymus, N=2; dot color indicates genotype) by flow cytometry.

We validated these findings by performing flow cytometry with multiple markers in 4-week-old thymus (time point used for all previous experiments, all of normal size) or 10-week-old thymus (of normal and enlarged sizes). As described by Dudgeon et al [43], T-cell clonal expansion preceding thymic lymphomas in p53-knockout mice can be detected at 9 weeks of age. Because we wanted to understand differences both early and later during disease progression, we decided to analyze thymic T-cell populations at 4 and 10 weeks.

In 4-week-old thymi, p53+/−, p53AD/−, and p53-null samples had comparable percentages of CD8+CD4− T cells (Figure 4F, left panel). However, an increase in numbers of CD8+CD4− T cells that lack TCR-β and TCR-γδ in the surface was observed for p53-null (with one sample around 50%), while the frequency of TCR-defective cells in p53AD/− and p53+/− was lower and less variable (Figure 4F, right panel).

At 10 weeks, consistent with our scRNA-seq results, CD8+CD4− T cells were the main cell type found in enlarged thymi (~70%, regardless of the genotype, Figure 4F, left panel). Interestingly, enlarged thymi showed higher incidence of CD8+CD4− T cells that lack TCR-β and TCR-γδ on the surface (Figure 4F, right panel) vs normal-sized thymi. This may suggest that immature CD8+CD4− TCR− cells undergo erratic proliferation to give rise to thymic lymphomas, possibly arising between the DN and DP maturation stages. These findings support our hypothesis that p53 dimers inhibit abnormal differentiation of T-cells in the thymus and that the PPAR pathway plays an important role in those activities.

p53AD promotes systemic biological changes

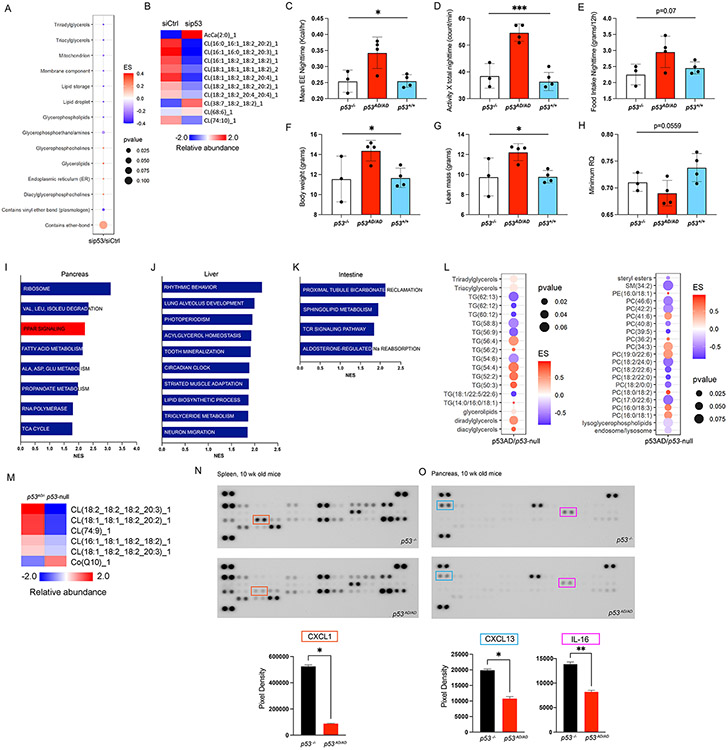

To interrogate metabolite differences directly resulting from p53AD activities, we knocked down (KD) p53AD in thymocytes and analyzed global lipidome profiles. Interestingly, several lipid classes were modulated by p53AD KD, with mitochondrial lipids being notably downregulated (Figure 5A-B). Cardiolipins, downregulated by p53AD KD, are essential constituents of mitochondria and play a role in processes such as oxidative phosphorylation [44] (upregulated in p53AD thymocytes), suggesting lower mitochondrial functionality in the absence of p53AD. Another mitochondrial lipid, acetyl-carnitine (AcCa(2:0)), an intermediate for fatty acid entry and breakdown in mitochondria, accumulated in p53AD KD samples, further indicating the negative impact of p53AD KD on mitochondrial function (Figure 5B). Furthermore, ether bond-containing lipids, which participate in organelle biogenesis, accumulated upon p53AD KD, suggesting p53AD supports this process. These results are consistent with higher mitochondrial activity in the presence of p53AD, as suggested above by RNA-seq (Figure 3A-B, Figure 4E).

Figure 5. p53AD promotes systemic biological changes.

A. Lipid ontologies affected by p53AD knock-down (KD) in p53AD/− thymocytes treated with siCtrl or sip53 (N=3/group). ES is enrichment score. B. Changes in mitochondrial lipids in thymocytes. CLAMS test in p53−/− (N=3), p53AD/AD (N=4), and p53+/+ (N=4) female mice shows increase in energy expenditure -EE- at nighttime (C), nighttime ambulatory activity (D), nighttime food intake (E), body weight (F), lean mass (G), and minimum respiratory quotient (RQ, or respiratory exchange ratio – RER) (H) in homozygous dimer mutant mice. *p<0.05, **p<0.004, ***p<0.0005. Pathways upregulated in p53AD/− vs p53−/− basal tissues through RNA-seq in pancreas (I), liver (J), intestine (K) (N=3/group). L. Lipid ontologies with changes in blood from p53AD/− vs p53−/− mice (N=2/group). M. Mitochondrial lipid changes in blood from p53AD/− vs p53−/− mice. Cytokine array analysis from 10-week-old basal spleen (N) or pancreas (O) from p53−/− and p53AD/AD mice. Quantification of the most significantly different cytokines per tissue are plotted below.

Our findings of p53AD activities in the thymus led us to hypothesize that p53AD may also have systemic effects as these mice carry germline alleles. To this end, we performed the Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS) test to interrogate whole-body metabolic differences between p53AD/AD, p53−/−, and p53+/+ mice. We found significant differences among these genotypes that were predominantly evident at night when mice are active: p53AD/AD mice had higher energy expenditure, ambulatory activity, and a trend for higher food intake than p53−/− and p53+/+ mice. Body weight, and lean mass of p53AD/AD mice were also higher (Figure 5C-G). The observed higher energy expenditure is likely explained by a combinatorial effect of both higher lean mass and physical activity. Under fasting conditions, p53AD/AD mice attained a lower respiratory exchange ratio (RER or RQ) than mice of other genotypes indicative of a higher contribution of fat oxidation to energy production (Figure 5H), a response that is consistent with the actions of PPAR-α [45]. These results suggest p53AD activities result in substrate utilization and behavioral changes that influence metabolic rates of mice.

Moreover, we performed RNA-sequencing of common metabolic tissues such as the pancreas, liver, and the intestine from p53AD/− and p53−/− mice. We found an upregulation of metabolism-related pathways in all tissues that contained p53AD, including PPAR signaling upregulation in the pancreas (Figure 5I-K). Additionally, we assessed metabolite differences in the blood of these mice. We found several changes in lipid abundance, in blood from p53AD/− mice as compared to p53−/− mice, with notable decrease in lipids that contain long-chain fatty acids (Figure 5L), suggesting higher lipid catabolism in the presence of p53AD. In addition, mitochondrial cardiolipins were upregulated in p53AD/− blood (Figure 5M), likely associated with the aforementioned increase in mitochondria functionality. It was also notable that CoQ was downregulated in p53AD/− blood, consistent with higher consumption of this compound required to support the increased mitochondrial function. Overall, these data identify novel molecular changes in several tissues containing p53AD.

Lastly, since PPARs are known to induce anti-inflammatory effects [46], we interrogated whether p53AD/AD and p53−/− tissues differ in their cytokine profiles. We analyzed spleen and pancreas samples from these mice on a cytokine panel. We found a significant downregulation of CXCL1 in p53AD/AD spleens, as well as downregulation of CXCL13 and IL-16 in p53AD/AD pancreas, as compared to p53−/− tissues (Figure 5N-O). These data suggest p53AD activities through PPAR activation may lead to a systemic anti-inflammatory phenotype. The extent to which this may contribute to tumor suppression needs to be further explored. Taken together, these data support a systemic effect of p53AD activities related to mouse behavior, lipid metabolism, and inflammation, although their combined role in tumor suppression remains elusive.

Discussion

We have modeled p53TD mutants in the mouse and provide direct support for their role in tumorigenesis as well as novel functions of dimeric p53. A monomeric p53 mutation is equivalent to p53 loss in all assays examined. On the other hand, p53AD (dimers) have certain tumor suppressive properties and non-canonical transcriptional activities (Supplementary Figure S9). Mice bearing p53AD alleles showed longer survival and lower tumor penetrance (LFS cohort) as compared to mice with deletion or monomeric p53. These data are consistent with patient data, indicating inheritance of a dimeric mutant TP53 allele lowers cancer penetrance and increases survival as compared to patients with monomeric and DNA Binding Domain mutants [13].

These mice were prone to tumor development, although with a shifted tumor spectrum that shows a reduction in thymic lymphoma incidence. p53AD is unable to induce apoptosis upon DNA damage in vivo. In addition, p53 dimer alleles rescue the apoptotic lethality caused by Mdm2 deletion. This is evidence of their failure to physiologically induce one of the main p53 pathway outcomes, that is apoptosis [2]. Lastly, p53 dimers do not transactivate common p53 target genes upon IR exposure, suggesting that they may not be able to execute other common WT p53 outcomes, such as cell cycle arrest or senescence. Our data implicate non-canonical activities of p53 dimers in suppression.

p53AD elicits tumor suppression through enhancement of the PPAR pathway. Under basal conditions, p53AD upregulates 33 direct PPAR target genes, including the Ppar-α and Ppar-γ isoforms themselves. This activation is dependent on the presence of dimeric p53, as knock-down of p53AD resulted in down-regulation of these genes. Furthermore, the PPAR pathway is dampened in p53AD/− thymic lymphomas, supporting a protective role against tumorigenesis. Moreover, direct protein-protein interactions between p53 dimers and PPAR-α and PPAR-γ and co-localization of p53AD and PPAR-α in gene regulatory regions, suggest the possibility that the unstable binding of p53AD to DNA [5] may be overcome by cooperative binding to PPARs, enhancing their transcriptional program. Genes bound by both p53AD and PPAR-α were part of cell differentiation and chromatin organization pathways, suggesting that these processes and related outcomes may contribute to tumor suppression. Four genes were bound by p53AD or PPAR-α and upregulated: Fabp4, indirectly regulates transcription by allowing fatty acid transport into the cell that serve as ligands for PPARs; Hadh, participates in fatty acid β-oxidation in the mitochondria; Glul, encodes glutamine synthetase; and Dab2ip, inhibits the PI3K-Akt pathway. The data suggest direct p53AD/PPAR-α binding to genes, activities of which are transcription dependent and independent, as well as potential p53AD cooperation with other transcription factors and co-activators, such as PPAR-γ or CCNC. Together these mechanisms may contribute to the transcriptional program elicited by p53AD. Additional data presented for WT p53 and other cancer-relevant dimeric p53 mutants suggest our findings can be extrapolated to other dimers of p53.

PPARs are ligand-activated nuclear receptors that act as transcription factors to modulate several cellular processes, mainly associated to cellular metabolism and differentiation [47]. In T-cells, PPAR-α and PPAR-γ have an inhibitory role in T-cell activation and proliferation [42]. In our model, p53 dimers halt proliferation of immature CD8 single positive T-cells, and allow for proper differentiation, by upregulating the PPAR pathway and its related cellular processes of oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid metabolism. This metabolic re-programming is a common feature of cell differentiation processes [48, 49]. Taken together, these data support a novel tumor suppressive role for p53 dimers via stimulation of the PPAR pathway. In the thymus, p53AD knock-down leads to a decrease in several lipid classes, including mitochondrial lipids, suggesting p53AD may regulate mitochondria number and function. Importantly, PPAR activity is linked to mitochondrial biogenesis and function [47]. Beyond the thymus, we observed p53AD has systemic effects in mice as evidenced by altered activity patterns, fasting substrate oxidation, tissue metabolic changes, and anti-inflammatory phenotypes, likely having an impact on tumor suppression.

PPAR agonists present a therapeutic opportunity. A study of the effects of restoring WT p53 in murine thymic lymphomas revealed that sensitive tumors upregulate expression of the retinoic acid receptor gamma (Rarγ) [50]. Pharmacological activation of RARγ synergized with genetic p53 restoration in inducing tumor cell apoptosis and differentiation [50]. The synthetic retinoid employed, CD437, also promotes PPAR-γ activation [51], providing evidence for the therapeutic potential of such agents. Importantly, defining the context in which PPAR agonists may work as tumor suppressors will be very important, as conflicting roles for PPARs in cancer have been reported [29-34]. For example, PPAR agonists can mitigate incidence of inflammation-induced cancers [32], induce terminal differentiation of breast cancer cells in culture [30, 52], and reduce the frequency of spontaneous immortalization of LFS-derived breast epithelial cells [53]. Importantly, loss-of-function mutations in PPAR-γ have been associated with colon cancer [29]. On the other hand, activating mutations in PPAR genes have been associated with luminal bladder tumors [35], highlighting the importance of context for the use of PPAR agonists. Currently, PPAR agonists are widely used to treat metabolic syndromes [47]. A retrospective study on LFS patients and the use of PPAR agonists (to treat metabolic syndromes) could inform on their potential role as an anti-cancer preventative strategy.

Methods

Generation of p53R339P (RP) and p53A344D (AD) mutant mice

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene targeting was used to generate our mouse models. Single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) were designed to target Cas9 to the site of interest (p53RP: GTAAACGCTTCGAGATGTTC, p53AD: GATGTTCCGGGAGCTGAATG). Single-stranded DNA donors containing the desired missense alterations, as well as silent mutations (introduced to avoid re-cutting of the locus once homologous recombination occurred and that do not alter amino acid sequences), and two 60-base pair homologous arms, were designed as repair template for homologous recombination after double strand breaks (p53RP ssDNA: GCTGTCTCCAGACTCCTCTGTAGCATGGGCATCCTTTAACTCTAAGGCCTCATTCAGCTCAGGAAACATCTCGAAGCGTTTACGCCCGCGGATCTGCAGCAGAGATGAAGTGAGATGGAAGCACTG, p53AD ssDNA: CCTGGAGTGAGCCCTGCTGTCTCCAGACTCCTCTGTAGCATGGGCATCCTTTAACTCTAAGTCTTCGTTCAGCTCCCGGAACATCTCGAAGCGTTTACGCCCGCGGATCTGCAGCAGAGATGAAGTG). Fertilized eggs were electroporated with the sgRNA, donor DNA, and commercial Cas9 protein, and implanted into C57BL/6J female mice at the Genetically Engineered Mouse Facility (GEMF) at MDACC. DNA extracted from pups was subjected to amplification by PCR for p53 exon 10 and flanking regions (Forward primer: 5’AGTCCACCTAACCCACAACTG 3’, Reverse primer: 5’ACTTCCCCAAATCCTCCTGAC 3’), followed by Sanger sequencing (primer: 5’ACTTCCCCAAATCCTCCTGAC 3’) to detect mutation presence. Founder animals were identified for both p53RP and p53AD, and were assayed for predicted off-target events (by PCR followed by sequencing of the top predicted off target sites – Supplementary Table S1). For further elimination of potential unpredicted off-target events, founder mice were back-crossed twice to C57BL/6J mice.

For genotyping, mouse ears were used for DNA extraction (200 uL 0.05M NaOH, incubation at 95 °C for 30’; followed by addition of 10 uL 1M TRIS, pH=8.0). Primers used for PCR reactions to detect mutant alleles can be found in Supplementary Table S7. For genotyping of homozygous mutant RP and AD mice, we performed two separate PCR reactions with primers to detect mutant alleles or wild-type alleles (Supplementary Table S7). An animal was considered as homozygous by the presence of a mutant allele band and absence of WT allele band. This was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (PCR primers Forward primer: GGTTGTGTGACCTTGTCCAG, Reverse primer: AGCAGGGTGGGGTTTTTATCT. Reverse primer was used for Sanger sequencing).

Animal studies

All mouse studies were conducted in compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal research and approved by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. LFS and LOH mouse cohorts were of mixed background 50% C57BL/6J −50% BALB/c. p53Mut/Mut cohorts were of varying mixed C57BL/6J - BALB/c percentages. Cohorts to age were established and followed up to two years. Genotyping of Mdm2 status and p53-null allele presence was carried out as described previously [25, 54]. For DNA damage response assays, mice were irradiated using sub-lethal IR (6-Gy whole-body), euthanized 4 hours post-IR, and tissues were harvested. Tissue portions were used fresh, flash frozen, or fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin saline.

MEFs generation and maintenance

Mice of desired genotypes were mated, and females were checked for plugs every day until a plug was detected (Day 0.5). At day 13.5, pregnant female was euthanized and embryos were isolated. Embryo’s liver was removed for genotyping purposes. Embryos were diced into very small fragments. Trypsin-EDTA (GenDEPOT) was added and incubated for 5-10 minutes. Complete culture media [C-DMEM: DMEM (Sigma) + 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma) + 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (GenDEPOT)] was added to neutralize trypsin. Cells were incubated at 37°C in C-DMEM, and media was changed the following day. When cells reached confluency, they were treated with trypsin and transferred into new plates with C-DMEM or resuspended in freezing media (C-DMEM+ 10% DMSO) and stored in liquid nitrogen for future use.

Chemical crosslinking assay for p53 oligomerization status determination

Starting material (pelleted MEFs or pulverized thymus) was resuspended in lysis buffer (1X PBS, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 100mM KCl. Added fresh: 10mM EDTA, 100X PMSF, 5mM DTT, 100X PIs, 1mM MgCl2 1mM, 1mM CaCl2) and incubated at 4°C rocking for one hour. Samples were centrifuged at maximum speed for 10 minutes at 4°C. Protein concentration was measured and adjusted to the highest amount of protein in the same volume for all samples. 25uL of lysate were aliquoted into as many tubes as glutaraldehyde concentrations desired per sample. 1uL of GA was added from stock solution (25% aqueous solution, Sigma 354400) to yield the desired final concentration (0-0.01%) and samples were shaken at room temperature for 20 minutes. Reaction was stopped with SDS-loading buffer and samples were boiled at 95°C. Samples were resolved in 4-20% gradient SDS-PAGE gels (Biorad 4561096) and detected using CM5 rabbit polyclonal antibody (P53-CM5P-L; Leica Biosystems) in the Biorad Chemidoc Imaging System.

Histopathology, Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Formalin-fixed tissues were processed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned (5μm), and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained by the MD Anderson Department of Veterinary Medicine and Surgery Histology Laboratory. H&E stained sections were evaluated for diagnosis of tumor type by a board-certified veterinary pathologist.

Immunohistochemistry: formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were used for immunohistochemistry following standard methods (Vector Laboratories). Staining was performed with antibodies against p53 (1:500, P53-CM5P-L; Leica Biosystems, Tris-EDTA pH 9.0 for antigen retrieval), cleaved caspase-3 (1:200, Cell Signaling Asp175 5A1E, citrate buffer pH 6.0 for antigen retrieval) or 4-HNE (1:200, Abcam ab48506, citrate buffer pH 6.0 for antigen retrieval). Visualization was performed using ABC and DAB kits (Vector Laboratories PK-4000, SK-4100), and hematoxylin was used as counterstain. Slides were examined by light microscopy. ImageJ (Fiji extension) software was used to determine percentage of positive area.

Immunofluorescence: formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were used for CD3 and B220 detection with ab5690 (Abcam) and RA3-6B2 (eBioScience) antibodies respectively (1:500 dilution, citrate pH 6.0 buffer for antigen retrieval). Alexa 488 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa 550 goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Thermo-Fisher) were diluted in PBS (1:3000) containing 1:10000 DAPI for nuclear staining. Coverslips were mounted using VECTASHIELD antifade mounting medium without DAPI (Vector Laboratories). ImageJ software was used to determine percentage of positive area.

Co-Immunoprecipitation

Flash-frozen tissues were pulverized using mortar and pestle, or MEF pellets, and homogenized in NP-40 buffer containing a protein inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 10 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF). Samples were incubated rocking for 1h at 4°C, then spun down for 10 minutes at 12000 rpm. Protein was quantified from supernatants. 1.5 mg of protein was used per immunoprecipitation (IP). 10% was set aside for input controls. Protein A/G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were used for a pre-clear step (1h at 4 degrees), followed by sample incubation with p53 antibody (1uL per IP, P53-CM5P-L; Leica Biosystems) or PPAR-α antibody (PA5-85125, Thermo-Fisher) overnight at 4 degrees. Beads were added to samples and incubated for 1 hour at 4 degrees. Beads were then recovered with magnets, washed twice with lysis buffer, and resuspended in protein loading buffer. Samples were boiled at 95°C for 5 minutes, and beads were separated with magnets. Supernatants were run on 10% SDS-PAGE gels. Antibodies used for detection of PPAR isoforms or p53: PPAR-α (PA5-85125, Thermo-Fisher), PPAR-γ (419300, Thermo-Fisher), PPAR-δ (PA1-823A, Thermo-Fisher), p53 (P53-CM5P-L, Leica Biosystems)

Protein isolation and Immunoblotting

Protein was isolated from pulverized frozen tissues or MEF pellets using NP-40 lysis buffer containing a protein inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 10 mmol/L PMSF. Samples were homogenized, incubated at 4°C for 1h in constant agitation, and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 12000 rpm. Supernatant was obtained and protein was quantified, then mixed with 6X loading buffer. Samples were boiled at 95 °C for 5 min to denature protein. Protein lysates were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with antibodies against p53 (CM5, P53-CM5P-L; Leica Biosystems), phosphorylated p53 at serine-15 (9284; Cell Signaling Technology), γ-Tubulin (ab11317; Abcam).

Real-Time qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cryo-pulverized tissues harvested from euthanized mice or cultured cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following standard manufacturer’s instruction. Total RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis kit (Biorad). qRT-PCR was performed as previously described using SYBR green (Bimake) on the CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Biorad) [55]. Expression levels for mouse genes of interest were normalized to Rplp0, and human genes normalized to GAPDH. Primers used are located in Supplementary Table S8.

p53 knockdown in primary thymocytes

Thymi from p53AD/− mice (4-week-old) were harvested and dissociated into single cells using a cell strainer (70 μm). Approximately 107 cells were used for electroporation following Amaxa Mouse T Cell Nucleofector Kit (Lonza) instructions. siRNA Universal Negative control (SIC001, Sigma) or siRNA targeting p53 (SASI_Mm02_00310137, Sigma) were used. Cells were plated into 12-well plates in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep, and harvested 24h later for further assays (RNA, protein extraction, lipidome profiling).

Flow cytometry

For apoptosis assessment: Thymus was harvested from euthanized mice and disassociated into a single cell suspension in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with Pen/Strep by cell strainer (70 μm). 2-4 x 106 cells were resuspended into binding buffer and incubated with Annexin V-FITC and/or PI following manufacturer’s directions (ApoAlert Annexin V Kit, Takara Bio). Flow experiments were performed on the Gallios 561 flow cytometer at the MDACC North Campus Flow Cytometry and Cellular Imaging Core Facility.

For T-cell characterization: Thymus was harvested from euthanized mice and disassociated into a single cell suspension in cold FACS buffer (PBS+2% heat-inactivated FBS+ 5mM EDTA) by cell strainer (40 μm). Cells were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 6 minutes at 4 degrees, and resuspended in FACS buffer. Volume was measured and recorded. Suspension was then filtered through 70 μm cell strainer, and cells were counted. 4x106 cells were added per tube in 100 uL volume, and antibodies were added to the cells (Supplementary Table S9). Propidium iodide (3μl/tube) was added immediately prior to experiment where appropriate. Tubes were incubated at 4 degrees for 15 minutes upon antibody addition, washed with FACS buffer and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 6 minutes at 4 degrees. Cells were resuspended in 700 uL FACS buffer and tubes were kept in dark until flow cytometry experiment. Cells were run through the Becton Dickinson LSR Fortessa FACS. All analysis was performed on Flow Jo analysis software (v10).

Bulk RNA-sequencing and analysis

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following standard manufacturer’s instruction and submitted to the M.D. Anderson Advanced Technology Genomics Core (ATGC) facility. Illumina compatible stranded total RNA libraries were prepared using the TruSeq® Stranded Total RNA kit (Illumina). Briefly, 250ng of DNase I treated total RNA was depleted of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ribosomal RNA (rRNA) using Ribo-Zero Gold (Illumina). After purification, the RNA was fragmented using divalent cations and double stranded cDNA was synthesized using random primers. The ends of the resulting double stranded cDNA fragments were repaired, 5′-phosphorylated, 3’-A tailed and Illumina-specific indexed adapters were ligated. The products were purified and enriched with 12 cycles of PCR to create the final cDNA library. The libraries were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (ThermoFisher) and assessed for size distribution using the 4200 TapeStation High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies), then multiplexed per pool. Library pools were quantified by qPCR using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit (Roche). Each pool was sequenced on one NovaSeq6000, S1 flow cell using the 100nt PE format.

RNA-seq FASTQ files were processed for quality control through FastQC. Samples that passed QC were taken into subsequent analysis. STAR alignment [56] was performed with default parameters to generate RNA-seq BAM files with GRCm38. Gene-level annotation was carried out using the GENCODE annotation [57]. Raw count data were processed and normalized by DEseq2 [58] software to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between sample groups. The final p-value was adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg method. A cut-off of gene expression log2 fold change of >=1.0 or <=−1.0 and an FDR q-value of <=0.05 was applied to select the most significant DEGs. Differential expression analysis was further evaluated utilizing the pathway enrichment tool GSEA [59] and IPA (Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, Ingenuity Inc). For thymus, pancreas, and intestine, we utilized the KEGG database for pathway analysis. For liver, we utilized Gene Ontology Biological Process (GOBP) database with an FDR<0.1 as KEGG components did not reach significance.

Motif analysis

p53 half-site sequences were generated with a combination of the Transfac p53 matrix [24]. PPAR response element (RE) sequences from target genes were obtained from the PPARgene website (http://www.ppargene.org/predictedtargets.php) an entered into MAST [60] as input motifs. Genomic sequences spanning 10Kb including a short intragenic region, transcription start site, and upstream regulatory region were entered as target sequences, for 33 p53 dimer-upregulated genes that are PPAR targets (See genomic regions utilized in Supplementary Table S4). Distance between PPAR REs and p53 half-sites was manually calculated considering closest sequences. We used Simple Enrichment Analysis (SEA) from MEME suite [61] to assess motif enrichment of p53 half sites in ATAC-seq differentially open regions, and in 26 PPAR target genes vs. a randomly generated list of 20 genes (genomic loci are described in Supplementary Table S5).

Whole Exome Sequencing and analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from tumors with DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen) following standard manufacturer’s instruction and transferred to the MDACC ATGC Facility. Illumina compatible libraries were prepared from 50ng of enzymatically fragmented; RNase treated DNA using the TWIST EF Library Preparation kit. Libraries were uniquely indexed and prepared for capture using 6 cycles of PCR amplification. Following amplification, libraries were assessed for size distribution using the 4200 TapeStation High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies Inc.) and quantity using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (ThermoFisher), then multiplexed 6-7 libraries per pool for capture. Exon target capture was performed using the TWIST Mouse Exome Panel (TWIST Biosystems). Following capture, the exon enriched libraries were amplified using 6 cycles of PCR then assessed for size distribution using the Fragment Analyzer High Sensitivity NGS Fragment Analysis (Agilent Technologies Inc.) and quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kits respectively. Libraries were multiplexed three captures (nineteen samples) per pool and the pool was quantified by qPCR using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit (Roche). The pool was sequenced on the NovaSeq6000 SP flow cell using the 150bp paired end format.

Log-ratio of read counts in tumor vs. pooled normal sample in target capture regions were estimated using Perl (version 5.10.1) and Samtools (version 1.4). Segmentation of the log-ratios were carried out using circular binary segmentation (CBS) algorithm [62] implemented in Bioconductor package DNAcopy in R environment (version 3.6.0). Regions of the genome that were significantly amplified or deleted across a set of samples were identified using GISTIC2 (version 2.0) [63]. We used a q-value threshold of 0.25 for differential peaks to continue with analysis of TSGs and oncogenes. Oncoprinter cBioPortal webtool (https://www.cbioportal.org/oncoprinter) was used to generate Oncoprints for tumors analyzed.

ATAC-sequencing and analysis

ATAC-Seq library preparation was performed at the MDACC Epigenomics Profiling Core. Nuclei were isolated form mouse thymus tissue following the previously published protocol [64]. Briefly, ~40mg tissue was homogenized in HB buffer [64] and passed through Flowmi strainer to achieve single cell suspension. The cell suspension was then centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C at 3,000 RCF in Iodixanol gradient (25-40%) and nuclei were collected, counted and subjected to ATAC-Seq library preparation following the Omni-ATAC protocol as previously described [65]. Briefly, 50,000 nuclei were transposed using Tn5 Transposase (TDE1, Illumina) in TD Tagment DNA buffer (Illumina) for 30 minutes at 37 °C, and the resulting library fragments were purified using a Qiagen MinElute kit. Resulting libraries were further amplified by 4–6 PCR cycles as described previously [65] and purified using SPRISelect beads (Beckman Coulter). These ATAC-seq libraries were sequenced 2 x 50 bp on an Illumina NovaSeq6000 to obtain at least 50 million high quality mapping reads per sample.

Programs trim_galore and cutadapt [66] were used for quality check of the FASTQ reads and to remove adapter sequences at the 3’ end of the reads. Bowtie2 [67] was used to align reads to the reference genome GRCm38. Samtools [68] was used to sort, convert between formats, and filter alignment files. Chromosome M (mitochondria) was removed from the alignments. Reads that were mapped to multiple locations were removed, and only reads that were mapped to unique chromosomal locations and properly paired were retained. Duplicated reads were also removed using PICARD. Peaks were called using MACS2 [69] , and peak annotation was carried out using HOMER [70]. The statistically significant differential open chromatin regions between p53-mutant and knockout samples were detected by using diffReps [71] . HOMER [70] was used for motif discovery/enrichment analysis on the statistically significant differential peaks. DEGs from RNA-seq data (different biological replicates were used to generate each dataset) were compared to differentially open regions to create a list of congruent genes (Supplementary Table S3).

Overexpression of human p53TD mutants

Lentiviral vectors encoding for human p53A347D, A347P, A347S or K351E mutant proteins (and EGFP) were synthesized by VectorBuilder. HEK293T cells were transfected following standard procedures. Cells were checked for EGFP expression, washed with PBS, and harvested in Trizol for RNA extraction.

ChIP-sequencing and analysis

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed at the Epigenomics Profiling Core, MD Anderson Cancer Center from pooled thymus samples, as described previously with some modifications [72]. Briefly, thymus tissue was broken into small pieces and crosslinked in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, followed by 125 mM glycine for 5 min. Nuclei were isolated from formaldehyde-crosslinked tissues/ChIP using buffers from chromatin shearing kit (Diagenode). The nuclei were lysed and subjected to sonication with a Bioruptor Pico (Diagenode) to obtain DNA fragments ranging 200-600 bp. The resulting chromatin lysate was precleared with Dynabeads Protein A (ThermoFisher) and incubated overnight at 4°C with p53 and PPAR-α antibodies (same as listed above) pre-conjugated with Dynabeads Protein A. The immunocomplexes were collected following day using Dynamag, washed, treated with RNase and Proteinase K, and reverse crosslinked overnight followed by DNA extraction. ChIP DNA and the corresponding input libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA library prep kit (New England Biolabs), and were sequenced using Illumina NextSeq500 instrument to obtain 30-40 million 75bp paired-end reads per sample.

Programs trim_galore and cutadapt [66] were used for quality check of the FASTQ reads and to remove adapter sequences at the 3’ end of the reads. Bowtie2 [67] was used to align reads to the reference genome GRCm38. Samtools [68] was used to sort, convert between formats, and filter alignment files. Chromosome M (mitochondria) was removed from the alignments. Reads that were mapped to multiple locations were removed, and only reads that were mapped to unique chromosomal locations and properly paired were retained. Duplicated reads were also removed using PICARD. Peaks were called using MACS2 [69] , and peak annotation was carried out using HOMER [70]. The statistically significant peaks were detected by using diffReps [71] . HOMER [70] was used for motif discovery/enrichment analysis on the statistically significant peaks. p53AD ChIP was performed in two technical replicates, and peaks obtained were combined. p53AD and PPAR-α -bound genes were introduced into GSEA for mouse gene sets to investigate gene ontologies using the Gene Ontology Biological Process (GOBP). Enrichment score was calculated by k (# of genes in overlap) divided by K (# of genes in pathway) *100 [k/K*100]. All FDR values were <0.005.

Single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and analysis

Murine thymi were isolated and rinsed with cold PBS containing Pen/Strep. Dissociation of single cells was carried out as described previously at protocols.io (https://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.t3aeqie). Following single-cell dissociation, samples were transferred to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) SINGLE core single-cell sequencing facility. The viability of the samples cell suspension was determined by Trypan Blue Stain (0.4%) for use with the Countess™ II FL, all samples had a viability of 90% or above. Cells then were resuspended in PBS with 0.04% BSA within the recommended range (800-1000 cells/μl) for loading at a volume to recover of 10,000 cells for scRNA-seq. Single cell capture, barcoding and library preparation were performed by following the 10X Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3′ protocol using 11-12 cycles for cDNA, and 14-16 cycles for libraries. The library size was measure using D1000 ScreenTape® and determined to be around 500-600 bp. Libraries were pooled to give a final concentration of 10 nM, pooled samples were further qPCR for final concentration before submission for sequencing with the NovaSeq6000 sequencer using the S2 100 cycles flowcell and sequence with 28 cycles for read1, 8 cycles for i7 index, and 91 cycles for read 2 through the ATGC core at MD Anderson. Reads from single cells were demultiplexed and aligned to the Genome Reference Consortium Mouse Build 38 genome (GRCm38) [73]. Samples were processed using the 10x Genomics Cell Ranger 6.1.2 v pipeline from fastq files to count matrices [74]. These count matrices were further analyzed using Seurat3 (v. 3.2.3) [75]. All libraries were required to have 200 genes per cell and each gene was required to appear in at least 3 cells. Cells with more than 5000 genes were filtered out. Dead and dying cells were filtered out using a mitochondrial percentage threshold of 15%. We used Harmony package for data normalization and integration. Canonical markers were examined to name clusters (Supplementary Figure S7B). Pathway analysis was performed using fGSEA package, FDR<0.1 was used to determine significance. Additional pathway analysis was performed using QIAGEN IPA software.

Metabolic phenotyping in live animals

The studies were conducted in compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal research and approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Body weight was measured with a calibrated integrating scale and body composition by quantitative magnetic resonance (QMR) (EchoMRI-100; EchoMedical Systems LLC, Houston, TX, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Metabolic phenotyping was carried out in female mice between 26-32 days of age. Prior to beginning metabolic measurements, mice were individually housed for 3 days in feeder cages, to acclimate them to the conditions of metabolic analysis. Mice were then individually placed into Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS) cages (Columbus Instruments Inc., Columbus, OH). Briefly, measures of VO2 and VCO2 were collected at half-hour intervals for four consecutive days. Food intake and locomotor activity were recorded concurrently at 1 min intervals. Energy expenditure was calculated by the Oxymax software package (Columbus Instruments) from the VO2, VCO2, and respiratory exchange ratio (RER) values using the Weir equation [76]. Data from the first 24 h were discarded to exclude atypical data associated with acclimation to the metabolic cages. Analyses and figures are based on mean values obtained over the remaining three days of complete recordings. On the fifth day, food was withheld over 7 hours starting at 6:00AM to assess resting metabolic rate. During this period, mice are naturally physically inactive and consume minimal food. The two lowest measures of energy expenditure were averaged to estimate resting energy expenditure in each mouse. The lowest RER value attained during this time was identified to assess substrate oxidation under fasting conditions.

Metabolite assessment and analysis

For blood metabolite analysis, mice were food-restricted for 6 h before blood collection. Blood (N=2/group) and thymocyte (N=3/group) samples were extracted using ice-cold ethanol containing 1% (v/v) 10 mM butylated hydroxytoluene and 1% (v/v) Avanti SPLASH® LIPIDOMIX® Mass Spec Standard (330707), both in methanol. Blood was extracted using 200 μL extraction solution and 10 μL whole blood. Samples were vortexed 5 min at room temperature then centrifuged at 17,000 g, at 4 °C, for 10 min. Supernatants were transferred to glass autosampler vials for immediate analysis. Injection volume was 10 μL. Mobile phase A (MPA) was 40:60 acetonitrile: water with 0.1 % formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate. Mobile phase B (MPB) was 90:9:1 isopropanol:acetonitrile: water with 0.1 % formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate. The chromatographic method included a Thermo Fisher Scientific Accucore C30 column (2.6 μm, 150 x 2.1 mm) maintained at 40 °C, autosampler tray chilling at 8 °C, a mobile phase flow rate of 0.200 mL/min, and a gradient elution program as follows: 0-3 min, 30% MPB; 3-13 min, 30-43% MPB; 13.1-33 min, 50-70% MPB; 48-55 min, 99% MPB; 55.1-60 min, 30% MPB. A Thermo Fisher Scientific Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer with heated electrospray ionization source was operated in data dependent acquisition mode, in both positive and negative ionization modes, with scan ranges of 150 – 827 and 825 – 1500 m/z. An Orbitrap resolution of 120,000 (FWHM) was used for MS1 acquisition and spray voltages of 3,600 and −2900 V were used for positive and negative ionization modes, respectively. Vaporizer and ion transfer tube temperatures were set at 275 and 300 °C, respectively. The sheath, auxiliary and sweep gas pressures were 35, 10, and 0 (arbitrary units), respectively. For MS2 and MS3 fragmentation a hybridized HCD/CID approach was used. Each sample was analyzed using four injections making use of the two aforementioned scan ranges, in both ionization modes. Data were analyzed using Thermo Scientific LipidSearch software (version 5.0) and R scripts written in house.

Mouse cytokine array panel

Proteome Profiler antibody array for Mouse Cytokine Array Panel A was obtained from R&D systems (ARY006). Protocol was carried out exactly as directed by manufacturer’s instructions. Flash-frozen tissues were pulverized and lysed in 500 uL PBS with protease inhibitors and 1% Triton X-100, debris was removed by centrifugation at maximal speed for 10 minutes, and samples were assayed immediately. Dot Blots were analyzed using ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software. Mouse survival curves by Kaplan-Meier plots were analyzed by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests. Statistical significance was defined as p< 0.05. Chi-square test for goodness of fit was used to assess Mendelian inheritance patterns of genotypes derived from mouse crosses. Hypergeometric probability was used to define significance of group overlaps, using 17101 as number of mouse genes with human orthologs. For other comparisons, Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups, and multiple groups were compared using ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s or Fisher post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

New mouse models with TP53R342P (monomer) or TP53A347D (dimer) mutations mimic Li-Fraumeni syndrome. While p53 monomers lack function, p53 dimers conferred non-canonical tumor suppressive activities. We describe novel activities for p53 dimers facilitated by PPARs and propose these are “basal” p53 activities.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grants (CA82577 and CA047295 to G.L.), the American Society for Cell Biology IFCB International Training Scholarship Program Grant (to J.G-A.), the Dr. John J. Kopchick Fellowship (to J.G-A.), and CPRIT SINGLE Core User Group Grant (to J.G-A.). J.G-A. was supported by the Rosalie B. Hite Graduate Fellowship in Cancer Research and Tzu Chi Foundation Scholarship.

We acknowledge MDACC Core Facilities grant CA016672 (GEMF, ATGC, Flow Cytometry, Microscopy Laboratory, and Metabolomics Core Facility), RP180684 (CPRIT Single Cell Genomics Core Facility), and S10OD012304-01.

We thank members of the Lozano lab Denada Dibra, Chang Sun, Dhruv Chachad, Xiao Zhao, Peirong Yang, Akshita Mirani, and Annette Machado for support and suggestions. We also thank Nikita Williams for her support with experiments involving mice.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement:

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Data availability

Sequencing data are publicly available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number: GSE220966).

References

- 1.Wasylishen AR and Lozano G, Attenuating the p53 Pathway in Human Cancers: Many Means to the Same End. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2016. 6(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P, and Levine A, Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2008. 9(5): p. 402–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer SM, Wasylishen AR, Qi Y, Fowlkes N, Su X, and Lozano G, p53 drives a transcriptional program that elicits a non-cell-autonomous response and alters cell state in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2020. 117(38): p. 23663–23673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.el-Deiry WS, Kern SE, Pietenpol JA, Kinzler KW, and Vogelstein B, Definition of a consensus binding site for p53. Nat Genet, 1992. 1(1): p. 45–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberg RL, Veprintsev DB, and Fersht AR, Cooperative binding of tetrameric p53 to DNA. J Mol Biol, 2004. 341(5): p. 1145–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaglia G, Guan Y, Shah JV, and Lahav G, Activation and control of p53 tetramerization in individual living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(38): p. 15497–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajagopalan S, Huang F, and Fersht AR, Single-Molecule characterization of oligomerization kinetics and equilibria of the tumor suppressor p53. Nucleic Acids Res, 2011. 39(6): p. 2294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, Fraumeni JF Jr., Nelson CE, Kim DH, et al. , Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science, 1990. 250(4985): p. 1233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petitjean A, Mathe E, Kato S, Ishioka C, Tavtigian SV, Hainaut P, et al. , Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum Mutat, 2007. 28(6): p. 622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouaoun L, Sonkin D, Ardin M, Hollstein M, Byrnes G, Zavadil J, et al. , TP53 Variations in Human Cancers: New Lessons from the IARC TP53 Database and Genomics Data. Hum Mutat, 2016. 37(9): p. 865–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gencel-Augusto J and Lozano G, p53 tetramerization: at the center of the dominant-negative effect of mutant p53. Genes Dev, 2020. 34(17-18): p. 1128–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamada R, Nomura T, Anderson CW, and Sakaguchi K, Cancer-associated p53 tetramerization domain mutants: quantitative analysis reveals a low threshold for tumor suppressor inactivation. J Biol Chem, 2011. 286(1): p. 252–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]