Abstract

Political scientists and sociologists have highlighted insecure work as a societal ill underlying individuals’ lack of social solidarity (i.e., concern about the welfare of disadvantaged others) and political disruption. In order to provide the psychological underpinnings connecting perceptions of job insecurity with societally-relevant attitudes and behaviors, in this article the authors introduce the idea of perceived national job insecurity. Perceived national job insecurity reflects a person’s perception that job insecurity is more or less prevalent in their society (i.e., country). Across three countries (US, UK, Belgium), the study finds that higher perceptions of the prevalence of job insecurity in one’s country is associated with greater perceptions of government psychological contract breach and poorer perceptions of the government’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis, but at the same time is associated with greater social solidarity and compliance with COVID-19 social regulations. These findings are independent of individuals’ perceptions of threats to their own jobs.

Keywords: COVID-19, government psychological contract breach, job insecurity, social solidarity

The COVID-19 pandemic has suddenly and dramatically impacted nearly every aspect of life (Rudolph et al., 2021; Sinclair et al., 2020). Not only has it forced people to adjust to unaccustomed ways of living, but it has also disrupted the work arena, with the consequence of millions of people worldwide losing their jobs (ILO, 2020). Through its continuing ramifications for lives and livelihoods, the COVID-19 pandemic illuminates the interconnectivity between the individual, the society, work, and public life. As such, the events of the pandemic provide a useful context for examining how people’s perceptions about threats to their own jobs and threats to jobs more broadly in their society shape societally-relevant reactions.

In this regard, the political science and sociology literatures, as well as fledgling macro-level human resource management literature, point to insecure work as a driving factor shaping individuals’ views of the functioning of government and behavior towards others in society. These literatures particularly highlight the role of how individuals think others in society are affected by a particular event. For example, Cumming et al. (2020) distinguish individuals’ own experience of precarious work from their general sense of precariousness experienced by others at large. They argue that both, but especially the latter, contribute to a sense that the system of government ‘no longer works’ (p. 3). Rodger (2003: 403) cautions that lack of secure work can contribute to a ‘decivilizing tendency’ that can weaken empathy and concern about those less fortunate in society. Sennett (1998) likewise argues that a lack of durable employment relations affects how people approach their personal relationships outside work and their general attitudes towards others. These outcomes are particularly relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic. A regard for others has been identified as a key factor for behavior change needed in times of the pandemic (Drury et al., 2020). Further, commentators describe insecure work as a contributing factor to the ‘open-ended political crises’ in the US and UK (two of the three countries studied in the present research) that ‘raises questions as to the structural viability and sustainability of their national recipes’ (Cumming et al., 2020: 4).

Work psychological research offers some initial evidence on the general link between perceptions of personal job insecurity and trust in the government and attitudes towards immigrants in general (Billiet et al., 2014; Dekker, 2010; Selenko and De Witte, 2020; Van Hootegem et al., 2021). Yet, it remains silent on people’s perceptions of whether others in society experience job insecurity (i.e., the perceived prevalence of job insecurity). Indeed, although work psychological research has begun to recognize that perceptions of job insecurity and societal attitudes are related (e.g., Selenko and De Witte, 2020; Van Hootegem et al., 2021), these topics are still largely treated as separate areas. This separation fails to capture that people are embedded in social contexts, and their perceptions of their social context likely inform how they evaluate aspects of their own lives. As an unexpected career shock (Akkermans et al., 2020), the onset of the pandemic would be expected to motivate individuals to not only assess their own job security but also to construct an understanding of whether such insecurity is widespread across their society (Hällgren et al., 2018; Sandberg and Tsoukas, 2015). Social psychological research has found these perceptions of the social environment to be as or more important in shaping outcomes than an individual’s own experience or objective metrics (Buunk, 2001; Schmalor and Heine, 2021).

This article leverages sensemaking theory (Sandberg and Tsoukas, 2015; Weick, 1995) to build a perspective on job insecurity that considers both an individual’s perceptions of threats to their own job as well as perceptions of the extent to which perceptions of job insecurity are prevalent in their society. The latter we term perceived national job insecurity, capturing the perception that job insecurity is more or less widespread, independent of any perceived threats to the person’s own job. We examine the association between these two subjective job insecurity variables (perceived personal and perceived national job insecurity) and two sets of outcomes: reactions towards the governing institutions of society and reactions towards members of society. Our research takes place across three countries – the United States, the United Kingdom, and Belgium – allowing us to capture a range of individual perceptions of both personal and national job insecurity. Our interest is not in a comparative analysis of these three countries, although we do reflect on potential country differences in the discussion. Rather, because we are interested in how people subjectively perceive job insecurity in their environments, it is helpful to sample individuals across multiple environments.

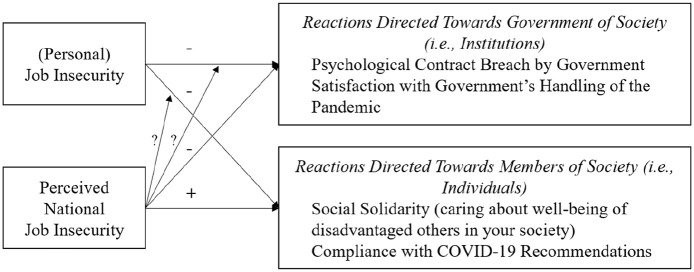

In doing so, we contribute to theory and research on people’s perceptions of their social environment, expand the nomological network of job insecurity to illustrate the potentially broad consequences of perceptions of insecure work, and provide insight into the psychological underpinnings of the link between job insecurity and societal outcomes (Sennett, 1998). Our work also offers practically relevant insights for addressing the pandemic and other economic crises. Our hypothesized model is displayed in Figure 1. In the following sections, we leverage sensemaking theory to describe why both perceived personal and perceived national job insecurity are likely to be relevant cognitions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. We then make predictions about how both sets of perceptions may relate to variables capturing reactions to government and variables capturing reactions to society.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of personal and perceived national job insecurity.

Perceived personal and national job insecurity during COVID-19

Sensemaking theory suggests that disruptive and ambiguous events lead individuals to question established ways of doing things and engage in a variety of efforts to make sense of these events and their implications (Sandberg and Tsoukas, 2015; Weick, 1995; Weick et al., 2005). There is consensus that the extra-ordinary event of the pandemic and ensuing economic crisis can be understood as a type of ‘shock’ that has disrupted nearly every aspect of people’s lives, including how they interact with others, their work, and their careers (e.g., Akkermans et al., 2020; Rudolph et al., 2021). These types of disruptive events tend to trigger a process of sensemaking and search for meaning. This process involves appraisal of how important aspects of one’s life might be affected (e.g., one’s own job security). Moreover, ‘sensemakers [are] concerned both to make sense of their selves and their external worlds’ (Weick, 1995: 20). Thus, sensemaking crosses the boundaries between the social and the individual as people seek to understand how events impact themselves and others, and what these impacts mean for how they should view and act towards the world around them (Brown et al., 2015). As Krueger (1998: 163) wrote, ‘humans, as social creatures continually perceive others and predict what others think, feel, and, most importantly, what they will do.’ In order to make sense of social reality, people will be particularly sensitive towards how others around them are coping and engage in social comparison processes (Buunk and Gibbons, 2007). We hence propose that it is not just the own personal situation that gets re-evaluated, but that this goes hand in hand with an inspection of the social environment as well.

Although economic phenomena can have both objective and subjective elements (e.g., Adler et al., 2000; Schmalor and Heine, 2021), our focus here is on the subjective. Job insecurity is defined as a person’s subjective perceptions that they are at risk of losing their current employment (De Witte, 1999; Shoss, 2017). Job insecurity is distinct from job loss in that it reflects the future-focused perception of a threat (Hartley et al., 1991; Lübke and Erlinghagen, 2014). Personal job insecurity reflects a person’s perception of risk to their specific job. In contrast, perceived national job insecurity concerns people’s perceptions of the extent to which others in their societies are experiencing threat. In other words, perceived national job insecurity captures the individual-level perception that job insecurity is relatively more or less common in one’s country.

We note that one can perceive that many individuals in society are insecure about their jobs while they do not themselves feel insecure. Additionally, these perceptions do not need to be shared by others in society or be accurate. Indeed, social isolation and dependence on differing media sources during the pandemic likely create a situation wherein people in a given society may develop varying perceptions of the extent to which job insecurity is widespread (Bendau et al., 2021). This makes perceived national job insecurity an especially important variable to examine when trying to understand individual reactions to the pandemic.

From a sensemaking perspective, we argue that individuals’ perceptions of personal and national job insecurity play an important role in how they make sense of and respond to the crisis. In particular, because the COVID-19 pandemic acts as a career-shock for people across society, people will pay attention to wider society when making sense of this event. This involves not only generating a sense of the proportion of people in society insecure about their jobs but also reacting to the government – whose role it is to build an economic and legal system that supports secure work – and to others in society – who may suffer in different ways from this event. Thus, the goal of our research was to examine how individual perceptions of national and personal job insecurity relate to variables that capture reactions to government and variables that capture reactions to society.

Perceived personal and national job insecurity and reactions to government

As an institution, government reflects the ‘humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interactions’ (North, 1991). In the countries included in our data collection (US, UK, Belgium), governments are often elected on the promises of helping their constituents achieve decent and secure work (e.g., ‘jobs, jobs, jobs’ was an election slogan during the last elections in Belgium; elected officials in the US and UK likewise campaign on promises about jobs). Thus, as individuals seek to make sense of the COVID-19 crisis, their perceptions of job insecurity are likely associated with reactions to their society’s government.

Specifically, we anticipate that job insecurity and perceived national job insecurity are related to people’s perceptions of psychological contract breach and satisfaction with the government’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis. Psychological contract breach refers to a person’s psychological understanding of the reciprocal obligations of an entity (in our case, government) and the person (Gough, 1978; Roehling, 1997). Such obligations may be explicit or implied, and perceptions of breach occur when there is a reneging or incongruence in expectations (Morrison and Robinson, 1997). Personal job insecurity may indicate to individuals that the government has failed in its obligation to provide stable work. Indeed, the notion of social contract, which formed the basis for the notion of psychological contract (Pesquex, 2012), originated from discussions about the contract between a government and its citizens: ‘For example, the governed promise to pay taxes, obey the laws, and share the risk of defense in exchange for security, protection, and opportunity for development provided by the state’ (Roehling, 1997: 205). In line with these arguments, a number of articles link personal job and financial insecurity to political distrust and dissatisfaction, suggesting that people blame their government for these conditions and may view them as a breach of the psychological contract (Emmengger et al., 2015; Haugsgjerd and Kumlin, 2020; Mughan et al., 2003; Van Hootegem et al., 2021; Wroe, 2014, 2016). The demand for government protection against employment losses occurring during the pandemic echoes these arguments (e.g., GOVTRUST Centre of Excellence, 2020; HM Treasury, 2021; Unite, 2020).

Perceived national job insecurity may likewise indicate that something about the ‘system’ is broken. In their social psychological studies of relationships, Buunk and colleagues argued that people use their perceptions of the social environment to gauge the likelihood that potential negative events could happen to them in the future (Buunk, 2001; Buunk and Van den Eijnden, 1997). For instance, the prevalence of others who are dissatisfied with their relationship could indicate the possibility that one’s relationship could become poor. Independently of the status of one’s own job, living in a society where one perceives job insecurity to be widespread, and where people fail to lead a dignified life may induce one to feel that the government has failed in its obligations (perceived psychological contract breach) and to be dissatisfied with the government’s handling of the crisis. Awareness of fellow citizens in insecure jobs further makes the collective context more cognitively salient, which should direct one’s focus towards remedies and measures not undertaken on a collective level (Turner et al., 1994). Indeed, this argument has been made by those seeking to understand the roots of political disruption (e.g., Cumming et al., 2020), although research is needed at the individual psychological level.

Hypothesis 1. Perceptions of personal job insecurity are (a) positively associated with perceived government psychological contract breach, and (b) negatively associated with satisfaction with the government’s handling of the pandemic.

Hypothesis 2. Perceptions of national job insecurity are (a) positively associated with perceived government psychological contract breach, and (b) negatively associated with satisfaction with the government’s handling of the pandemic.

Perceived personal and national job insecurity and reactions towards members of society

Although personal job insecurity and perceived national job insecurity may relate similarly to reactions to government, we anticipate that personal job insecurity and national job insecurity may have conflicting relationships with reactions to others in society. Past research suggests that job insecurity creates a protective, self-focus where individuals are less concerned with others and behave less helpfully towards others (Billiet et al., 2014; Sverke et al., 2019). Indeed, job insecurity has been associated with negative views towards immigrants (Billiet et al., 2014) and interpersonal mistreatment (Shoss et al., 2018). Hence, the extant theory and research on job insecurity suggests that job insecure individuals would be less concerned with the welfare of others as they focus their attention on the self and perhaps view others as potential competition for jobs and resources.

In contrast, a high concern about national job insecurity indicates an awareness of others in society, a sense of awareness of a collective. This awareness makes positive action and solidarity towards that collective more likely. To this point, disaster research shows that such events can create a sense of shared fate independently of personal suffering, and hence generate collective solidarity and helping behavior (Elcheroth and Drury, 2020). Rodger (2003) also describes how solidarity may emerge from a need for mutual insurance. In an environment where job insecurity is perceived to be high, people may be particularly attuned to the need to care about and protect others in hopes that others will do the same if/when the individual needs help for themselves (Buunk, 2001).

We hence arrive at two different predictions for the relationships between personal and perceived national job insecurity and our societally-oriented outcome variables: social solidarity (expressed concern about the well-being of those less fortunate in society) and compliance with COVID-19 social mitigation recommendations. Social solidarity is defined as expressed concern about the well-being of those less fortunate in society (Méda, 2019). Social solidarity is considered crucial for society’s ability to address the COVID-19 pandemic and other extreme events (Drury et al., 2020). It is also argued to underlie public policy considerations regarding the welfare state because such views shape the policies that are politically palatable (Van Oorschot, 2006). As such, questions about social solidarity are regularly asked on societal surveys such as the European Values Survey. It is important to note that perceived national job insecurity is distinct from social solidarity. Whereas perceived national job insecurity reflects a prevalence judgment about others’ job insecurity, social solidarity reflects concern about the experiences of those who are disadvantaged in society. There are many reasons why these may diverge (e.g., Van Oorschot, 2006). However, in our study, we anticipate that viewing job insecurity as particularly prevalent in society may enable a sensemaking about the nature of society that lends itself to greater concern about those who are disadvantaged by the current societal system. In contrast, based on the logic that personal job insecurity narrows one’s focus on one’s own interests, we anticipate that personal job insecurity is negatively associated with social solidarity (Billiet et al., 2014; Sverke et al., 2019).

Compliance with COVID social recommendations, particularly at the time our research was conducted, was described in all three study countries as measures to protect others, especially those in vulnerable populations. In other words, while compliance with COVID-19 hygiene recommendations was communicated as a way to protect the self from COVID-19, compliance with COVID-19 social recommendations was hailed as a way to protect others (Pfattheicher et al., 2020). Moreover, actions to reduce the spread of the virus enhance society’s ability to forestall the economic damage that would result from the virus spreading unchecked. Thus, we view compliance with COVID-19 social recommendations in line with Johnson et al. (2020), as a potential behavioral indicator of the extent to which individuals engage in cooperative action for the good of others in society. In line with the arguments above, we anticipate that perceived national job insecurity engenders a social awareness that may heighten the likelihood of people complying with COVID-19 social recommendations. In other words, awareness of risks to a large number of others’ jobs would be associated with greater efforts on the part of individuals to engage in behavior that is socially responsible. In contrast, personal job insecurity would be anticipated to relate negatively to compliance with COVID-19 social recommendations in line with the rationale described above.

Hypothesis 3. Perceptions of personal job insecurity are negatively associated with (a) social solidarity and (b) compliance with COVID-19 social recommendations.

Hypothesis 4. Perceptions of national job insecurity are positively associated with (a) social solidarity and (b) compliance with COVID-19 social recommendations.

Exploring potential interactions between perceived national job insecurity and personal job insecurity

We also inquired, in an exploratory manner, whether personal and national job insecurity might interact to predict both sets of outcomes. It is plausible that these two perceptions interact, as individuals rarely form an evaluation about aspects of their life independently of their social environment. Indeed, self-evaluative assessments about one’s own status, whether one is well or worse off, depend on comparisons – with oneself in the past or with other people. Perceived social context has been found to influence how people assess various matters of their own life, ranging from burnout (Carmona et al., 2006) to their satisfaction with their economic situation (Schmalor and Heine, 2021), even their individual relationships (Buunk et al., 2001). Similarly, we might expect that individual personal job insecurity gains meaning in a social context: if there is a sentiment that many people suffer from job insecurity in one’s nation, this might affect the seriousness of one’s own job being insecure. An interactive effect may therefore mean that perceived national job insecurity provides the interpretive context in which individuals make sense of their own insecurity. When perceived national job insecurity is high, individual job insecurity would be expected to more strongly relate to perceptions of psychological contract breach by the government and greater dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of the pandemic. In such conditions, individuals’ own job insecurity would be seen as part of a larger societal problem of job insecurity and thus they may be more apt to blame the government for these conditions. However, the combination of higher individual and higher perceived national job insecurity may lead to a greater sense of shared experience and, therefore, more social solidarity and socially-interested actions (Rodger, 2003). Given the lack of strong theory to propose an interaction, we examine this question in an exploratory manner.

Method

Participants and procedure

We examine our hypotheses with data from individuals across three countries. Because perceived national job insecurity captures one’s (however valid or invalid) perceptions of one’s society, capturing the implications of variance in these perceptions for outcomes requires sampling individuals across several different societies. This variance maximizing strategy allows for making more general inferences about a phenomenon that is theorized to occur across contexts. The samples were drawn from the US, the UK, and Belgium, three countries strongly affected by the pandemic with similar public health guidance. Further, our measure of personal job insecurity has also been previously translated and was widely used in these countries. As a result, utilizing these three samples allowed us to examine perceived national job insecurity and personal job insecurity transcending national boundaries in samples where the measurement of personal job insecurity has been previously validated.

Our study design utilizes self-report surveys assessed cross-sectionally. We chose a cross-sectional design because we anticipated that people’s perceptions of their own risk and their social environment influence sensemaking in a nearly immediate fashion. Further, we were interested in between-person effects, which cross-sectional studies can appropriately capture. We were also concerned that repeated measures studies would add too much participant burden during times of crisis, which could lead to the attrition of those who are more insecure. We deemed self-report appropriate because most of the concepts studied are inherently perceptual, and our measurement tests, presented below, suggest that individuals can distinguish among these constructs and do so in a way that is consistent across the countries involved in this research.

Data were collected by a survey panel company (Respondi) during the week of 13 July 2020. Panelists undergo a vetting process to verify their identity before they can join and the company itself holds several industry certifications to ensure the quality of their panels. The company sent out an invitation with a link to the survey to panelists who are registered with them in each of the three countries. The surveys themselves were hosted on the Qualtrics university accounts of the authors of this study; the survey company did not have access to the surveys or the data collected. Only employed respondents, between the ages of 18 and 65, who were residents of the respective countries received an invitation to the survey, and there was also a quota imposed to collect an equal number of men and women. Respondents could self-select into the survey and voluntarily withdraw at any time. The sampling stopped once the quota was filled.

The final sample consists of 453 British employed workers, 518 American employed workers and 460 Flemish (i.e., Dutch speaking region of Belgium) employed workers. Participants were informed that participation was completely voluntarily, that the survey was fully anonymous and that all answers would be treated confidentially. In return for their participation, respondents received token points that could be exchanged for small monetary rewards over the long-term. It is worth noting that our respondents are not a representative sample of the three sets of working populations – they are more highly skilled and overrepresented regarding (higher level) white collar workers. The study gained ethical approval by all three universities involved.

UK sample

The respondents’ mean age was 47.35 years (SD = 12.15). The majority of the sample was male (53%), indicated that they did not belong to an ethnic minority group (93%), and had finished some sort of tertiary education (56%). Based on the ISCO-08 classification codes, 9% were low skilled blue collar workers, 5% were high skilled blue collar workers, 32% were low skilled white collar workers, and 54% high skilled white collar workers. While 42% indicated they were working on site, 41% answered that they were working entirely from home. A total of 17% combined working on site with working from home, to various degrees.

US sample

On average, the respondents’ age was 46.67 years (SD = 12.04). More participants were male (50.3%), white (82%), and had a tertiary education degree (76%). A total of 5% were low skilled blue collar workers, 7% high skilled blue collar workers, 29% low skilled white collar workers, and 60% high skilled white collar workers. Whereas 47% responded that they did not work from home, 39% answered that they were currently working five days a week from home and 14% indicated that they worked some days of the week at home.

Belgian sample

The mean age of the sample was 45.49 (SD = 10.90). More than half of the participants were male (51%) and did not belong to an ethnic minority group (98%). Of the participants, 46% had completed tertiary education. A total of 15% were low skilled blue collar workers, 7% were high skilled blue collar workers, 39% were low skilled white collar workers, and 40% high skilled white collar workers. The majority of the sample did not work from home (52%), 31% stated that they were working completely from home and 17% partly worked from home.

Measures

Response alternatives ranged from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree), unless stated otherwise.

Perceived individual job insecurity was measured using the four-item Job Insecurity Scale (De Witte, 2000; Vander Elst et al., 2014; αUK = .91, αUS = .89, and αBelgium = .90). A sample item is ‘I think I might lose my job in the near future.’

Perceived national job insecurity was measured with four items which were developed for the purpose of this study (αUK = .88, αUS = .88, and αBelgium = .89). The scale was inspired by Låstad and colleagues’ (2015) references to the collective level of job insecurity in their job insecurity climate scale. We adapted the organizational level to the national context and mirrored the framing of the items of the Job Insecurity Scale (Vander Elst et al., 2014). Although the scale originally included a fourth and positively framed item, we omitted this indicator from the analyses due to a poor factor loading on the shared latent variable in all three countries. The final items were ‘In [country] there is a general feeling that many people will soon lose their jobs,’ ‘In [country] a lot of people feel insecure about the future of their jobs,’ and ‘In [country] many people think that they might lose their job in the near future.’ The standardized factor loadings per country are demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Standardized factor loadings of the configural invariance measurement model.

| Perceived national job insecurity scale | Factor loadings and estimates (SE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| UK | US | Belgium | |

| In [country] there is a general feeling that many people will soon lose their jobs | .84 (.03) | .78 (.03) | .80 (.03) |

| In [country] a lot of people feel insecure about the future of their jobs | .81 (.05) | .87 (.02) | .87 (.02) |

| In [country] many people think that they might lose their job in the near future | .86 (.04) | .89 (.02) | .88 (.02) |

Psychological contract breach by the government was assessed using four items from Robinson and Morrison’s (2000) psychological contract breach scale (αUK = .88, αUS = .84, and αBelgium = .83). References to ‘my employer’ were changed to ‘our country’s government’ to reflect attitudes towards the government instead of the organization (e.g., ‘We have not received everything promised to us by our country's government’).

Government satisfaction with handling the pandemic was measured by one item based on the government satisfaction item in the European Social Survey (2018). The item reads ‘How satisfied are you with the way in which your country’s government is handling the COVID-19 crisis?’ Responses ranged from 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 5 (extremely satisfied).

Solidarity was measured using five items based on the European Values Study (αUK = .86, αUS = .90, and αBelgium = .84). Respondents were asked the following: ‘When you think about the living conditions in [country], to what extent do you feel concerned about the living conditions of: . . .’. Subsequently, respondents had to indicate their degree of solidarity towards five groups of vulnerable people: elderly people, unemployed people, people affected by COVID-19, people in poverty, and people who worry about keeping their jobs. The last three groups were added for this study. Responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Compliance with COVID-19 measures was assessed using Nivette et al.’s (2020) compliance with COVID-19 social regulations measure (αUK = .78, αUS = .82, and αBelgium = .66). Using a four-point scale (1 = never, 4 = all of the time), respondents were asked to which degree they adopted the following protective behaviors in response to COVID-19: adhere to social distancing, avoid contact with people at risk, avoid groups, don’t shake hands, stay at home, wear a face mask in public, use public transport only when necessary, and stay home with symptoms. The last two items were excluded from the analyses because they did not load on a shared latent factor in any of the three countries. The item referring to wearing a face mask was omitted in all three samples due to a factor loading of .22 in the UK sample, perhaps due to the fact that mask-wearing wasn’t widely recommended at the time of data collection.

Analyses

The statistical analyses were performed by means of Mplus version 8.4 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017). We used a robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) for all analyses, which provides standard errors and fit indices that are robust to non-normality (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017). We used full information MLR estimation, which allows to use the data from all respondents by estimating parameters for missing data; 5%, 6%, and 6% of individuals in the UK, US, and Belgium, respectively, had some degree of missing data, with most respondents only having missing data on one or two items. This means that 94–95% of our sample had no missing data on any of the study variables we used in this research model. First the factor loadings and structure of the variables were examined using a confirmatory factor analysis. Then measurement invariance across samples was tested by imposing a sequence of restrictions on the countries’ measurement models. Configural invariance (i.e., no constraints) was compared to metric invariance (i.e., factor loadings) and scalar invariance (i.e., intercepts) models. Given that measurement invariance was reached, we continued with a pooled dataset. As recommended by Morin et al. (2016), we saved the factor scores of the most invariant model so as to preserve the measurement invariance structure when merging the different samples. Factor scores are a good alternative to manifest variables as they partially control for measurement error by assigning less weight to items with higher levels of measurement error. Furthermore, this strategy ensures comparability of the results across groups (Morin et al., 2016). We created an interaction term of the latent variables of perceived individual and national job insecurity using the ‘XWITH’ statement in Mplus, which was also saved as a factor score. We conducted structural equation modeling to test our hypotheses, in which we controlled for country to address any systematic country effects (Abadie et al., 2017). UK and US were included as dummy variables, with Belgium as the reference category. 1 We performed two supplementary analyses. First, given potential heterogeneity in country samples, we used coarsened exact matching (CEM; Blackwell et al., 2009) as a sensitivity check to examine the robustness of the findings. Second, we investigated whether similar findings emerge when examining solely within-country variability in the variables of interest. We conducted a multiple group analysis in which we used latent variables and took into account the measurement invariance.

Results

The configural model provided a good fit to the data (χ2 (537) = 1389.197, CFI = .933, TLI = .922, RMSEA = .058, SRMR = .052), with factor scores that were all well above the suggested threshold of .40 (Harrington, 2009). One exception to this was the ‘don’t shake hands’ item of the COVID-19 measures scale, which had a factor loading of .336 in the Belgian sample. However, we chose to include the item as it appeared to be a good indicator of the shared latent factor in the two other countries, and as the loading in the Belgian sample was not far below .40. The results supported metric invariance of the measurement model (χ2 (569) = 1445.061, CFI = .931, TLI = .924, RMSEA = .057, SRMR = .055), as indicated by a ∆CFI that was less than .01 and a ∆RMSEA that was below .015 (Chen, 2007; Cheung and Rensvold, 2002). However, we had to reject the scalar invariance hypothesis (χ2 (601) = 1618.329, CFI = .920, TLI = .916, RMSEA = .060, SRMR = .057), as the ∆CFI was above .01. We therefore proceeded with the metric invariance model, which suffices if mean levels are not compared (Little, 2013).

Table 2 shows, as expected, individual and national job insecurity correlate positively but not very strongly with each other, confirming the discriminant validity of the two variables. Table 3 presents the results of our structural equation model in which satisfaction with government, psychological contract breach by government, solidarity, and compliance with COVID-19 measures were regressed on perceived individual and national job insecurity, and their interaction term. In line with our expectations in Hypotheses 2a and 2b, perceived national job insecurity was related to greater perceived breach of the psychological contract by the government (b = .39, SE = .03, p < .001), and with lower satisfaction with the government’s handling of the pandemic (b = –.32, SE = .06, p < .001). Contrary to Hypotheses 1a and 1b, individual job insecurity was negatively related to government psychological contract breach (b = –.08, SE = .03, p = .02), and not related to government satisfaction (b = –.07, SE = .04, p = .09). No significant interaction effects emerged for government psychological contract breach (b = –.05, SE = .03, p = .42) or for satisfaction with the government’s handling of the pandemic (b = .13, SE = .07, p = .06).

Table 2.

Pearson correlations of personal and national job insecurity with COVID-19 relevant outcomes.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Personal job insecurity | 2.09 | .98 | (.90) | |||||

| 2. | Perceived national job insecurity | 3.88 | .74 | .18 ** | (.87) | ||||

| 3. | Psychological contract breach government | 3.38 | .95 | .02 | .18 ** | (.85) | |||

| 4. | Government satisfaction | 2.65 | 1.30 | –.08 ** | –.13 ** | –.61 ** | – | ||

| 5. | Solidarity | 3.65 | .81 | .13 ** | .27 ** | .16 ** | –.08 ** | (.87) | |

| 6. | COVID-19 compliance | 3.36 | .55 | .03 | .17 ** | .01 | .03 | .26 ** | (.77) |

p < .01.

Table 3.

Unstandardized structural coefficients (and standard errors) of job insecurity, national job insecurity and their interaction explaining COVID-19 relevant outcomes.

| PCB government | Satisfaction w/ government | Solidarity | COVID-19 compliance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE(b) | b | SE(b) | b | SE(b) | b | SE(b) | |

| Personal job insecurity | –.08 * | .03 | –.07 | .04 | .05 ** | .02 | –.02 | .01 |

| National job insecurity | .39 *** | .03 | –.32 *** | .06 | .32 *** | .03 | .14 *** | .02 |

| Personal × National | –.05 | .03 | .13 | .07 | –.02 | .03 | –.03 | .03 |

| UK (vs others) | –.01 | .07 | .26 ** | .08 | –.01 | .04 | .01 | .03 |

| US (vs others) | –.01 | .06 | –.10 | .08 | .01 | .03 | –.01 | .03 |

p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

As expected in Hypotheses 4a and 4b, perceived national job insecurity was positively related to both solidarity (b = .32, SE = .03, p < .001) and to compliance with COVID-19 social recommendations (b = .14, SE = .02, p < .001). In contrast to Hypotheses 3a and 3b, there was a positive and significant relationship between personal job insecurity and solidarity (b = .05, SE = .02, p < .01) and we did not find a significant relationship between personal job insecurity and compliance with COVID-19 measures (b = –.02, SE = .01, p = .28). The interaction term of personal and national job insecurity was not significantly related to either solidarity (b = –.02, SE = .03, p = .60) or compliance with COVID-19 recommendations (b = –.03, SE = .03, p = .21).

Supplemental analyses

As a robustness check against country heterogeneity, we conducted CEM analyses with demographic variables that were significant predictors of at least one of the outcomes (gender, occupation, politics, work hours), which left 330, 347, and 283 matched responses across the three datasets, UK, USA and Belgium, respectively. We then performed individual regressions of each dependent variable on the predictors. The results are largely consistent with our reported model in terms of the significant relationships between the variables, such that perceived national job insecurity significantly predicted government psychological contract breach (b = .31, SE = .05, p < .01), government satisfaction (b = –.15, SE = .07, p < .05), solidarity (b = .32, SE = .03, p < .01), and compliance with COVID-19 measures (b = .11, SE = .02, p < .01). The only change is that personal job insecurity became a significant predictor of satisfaction with government (b = –.13, SE = .05, p < .01). Consistent with the findings reported above, personal job insecurity was a significant predictor of government psychological contract breach (b = –.08, SE = .04, p < .05) and solidarity (b = .05, SE = .02, p < .01).

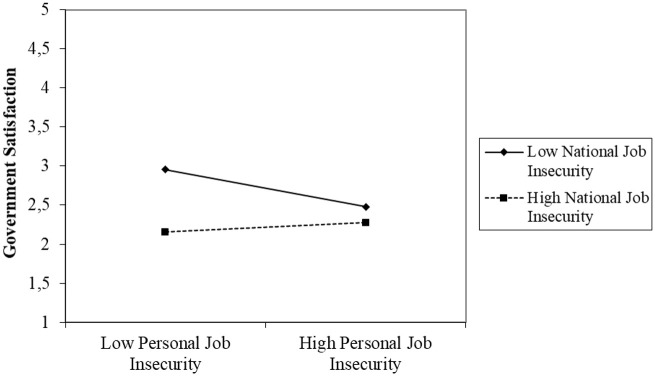

We additionally performed a multiple group analysis, the results of which are displayed in Table 4. It is important to note that these results are not directly comparable to the results above because they only speak to the implications of within-country variance in our predictors (e.g., the range of perceived national job insecurity observed within Belgium versus the range of perceived national job insecurity observed across the entire sample). Similarly to the pooled data, national job insecurity was significantly and positively related to both psychological contract breach by the government (bUK = .42, SE = .09, p < .001; bUS = .35, SE = .09, p < .001; bBelgium =.26, SE = .09, p < .001) and solidarity (bUK = .13, SE =.06, p = .04; bUS = .40, SE = .05, p < .001; bBelgium = .26, SE = .05, p < .001) within all three countries. In two of the three samples (the US and Belgium) national job insecurity was also significantly related to government satisfaction with handling the pandemic (bUS = –.36, SE = .09, p < .001; bBelgium = –.30, SE = .10, p < .001) as well as compliance with COVID-19 guidelines (bUS = .16, SE = .05, p < .001; bBelgium =.13, SE = .05, p < .001). When separately analyzing the countries, we found a significant relationship between personal job insecurity and solidarity only within the UK (bUK = .09, SE = .03, p = .01). In the pooled sample, we found a significant and negative relationship between personal job insecurity and psychological contract breach by the government. We found coefficients of a similar size in the separate analysis in the UK and Belgium, but effects were non-significant (bUK = –.10, SE = .06, p = .10; bBelgium = –.09, SE = .06, p = .13). We found a significant interaction effect of individual and national job insecurity on government satisfaction in the US (bUS = .22, SE = .10, p = .03). The nature of this relationship suggests that higher perceptions of national job insecurity are not necessarily associated with poorer outcomes of personal job insecurity; rather, higher perceptions of national job insecurity are associated with less benefit (in terms of government satisfaction) of lower personal job insecurity (see Figure 2).

Table 4.

Unstandardized structural coefficients (and standard errors) of individual and national job insecurity and their interaction predicting outcomes per country.

| UK | US | Belgium | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB gov | Sat. gov | Solidarity | Cov. com. | PCB gov | Sat. gov | Solidarity | Cov. com. | PCB gov | Sat. gov | Solidarity | Cov. com. | |

| Pers. job insecurity | –.10 (.06) | –.08 (.07) | .09 * (.03) | –.04 (.03) | –.03 (.07) | –.09 (.07) | .02 (.03) | .03 (.03) | –.09 (.06) | –.02 (.07) | .03 (.04) | –.04 (.04) |

| Nat. job insecurity | .42 *** (.09) | –.18 (.11) | .13 * (.06) | .08 (.05) | .35 *** (.09) | –.36 *** (.09) | .40 *** (.05) | .16 *** (.05) | .26 *** (.09) | –.30 *** (.10) | .26 *** (.05) | .13 *** (.05) |

| Pers. × Nat. job insecurity | –.08 (.11) | .04 (.13) | –.15 (.08) | .05 (.06) | –.06 (.11) | .22 * (.10) | .05 (.05) | –.09 (.05) | .02 (.12) | .01 (.14) | –.02 (.07) | –.05 (.07) |

Note. PCB gov = perceived psychological contract breach of the government; Sat. gov = satisfaction with the government; Cov. com. = compliance with COVID-19 measures. Standard errors in parentheses.

p < .05, ***p < .01.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect of perceived personal and national job insecurity on government satisfaction in the US.

Discussion

This study set out to introduce the concept of perceived national job insecurity (people’s perceptions about other citizens’ job insecurity) as a conceptual bridge to understand how insecure work may shape citizens’ reactions to government and others in society in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this study suggest that the perception of other citizens’ job insecurity is relevant for pandemic relevant behaviors and attitudes. Perceived national job insecurity is related to negative attitudes towards the government, in the form of perceived contract breach and lowered satisfaction, but at the same time it is positively associated with attitudes of solidarity and even compliance with COVID-19 health measures to protect the health of others. Importantly, it does so to a much higher degree than individual job insecurity does (e.g., Probst et al., 2020).

Implications for theory

This research widens current conceptualizations of job insecurity, which is understood as a mostly individual (or organizational) level phenomenon, driven by employment circumstances, and affecting individual and organizational behavior. We show that when it comes to understanding collectively relevant attitudes and behaviors, these outcomes are more associated with perceptions of the social environment than perceptions of one’s own personal risk.

What do these finding suggest about sensemaking in situations like the COVID-19 pandemic? We anticipated that perceptions of both personal and national job insecurity would be relevant to people’s responses to governments and other members of society. That is, in ambiguous situations, people would examine both their own experiences as well as their perceptions of what is going on around them and thus both would relate to our outcomes.

However, our findings suggest that it is an individual’s perceptions of others’ experiences and not necessarily their own experiences that shape how they view the system in charge of the collective (i.e., government) and others in their society. This may be a construal or target effect where perceptions targeted at a given level (e.g., macro-level government, society) are more strongly associated with reactions at that level. In other words, people’s judgments about the context of work seems particularly relevant to understanding people’s judgments and reactions to other elements of this context (i.e., institutions, people in society more generally). What seems clear from our study is that when it comes to nationally relevant behaviors and attitudes, it is the perceptions of the widespread nature of other citizens’ job insecurity, rather than one’s own, that plays a role.

Contrary to our expectations, individual job insecurity was related to more (and not less) solidarity, measured as concern for vulnerable groups. The effect in our study was small and could only be replicated in one of the three samples when analyzed separately, and thus should be interpreted with caution. If this is the case, then perhaps people who were job insecure felt more part of vulnerable groups in general, which heightened their solidarity with them. Selenko and De Witte (2020) similarly found that job insecurity led people to feel closer to and more solidarity with unemployed people. We also thought that perceptions of national job insecurity may provide an interpretive context for individual perceptions. In other words, individuals might compare their own experiences against the experiences they perceive others to have. However, perceptions of national job insecurity did not interact with individually felt job insecurity in relating to societal outcomes; although this might depend on the context. Data from the US showed that perceived national job insecurity seemed to matter more for satisfaction with the government when an individual’s job insecurity was lower. Future research might examine whether perceptions of national job insecurity moderate the relationship between personal job insecurity and personal outcomes, such as well-being (e.g., Green, 2011).

It is also interesting to consider the extent to which people’s perceptions of national job insecurity match their perceptions of their own job insecurity. The correlation between perceived personal and perceived national job insecurity was quite low (r = .18), suggesting a small amount of shared variance between the two sets of perceptions. This suggests that individuals are looking towards other elements of the social environment beyond their own job in developing perceptions of national job insecurity. Moreover, the observed mean for perceived national job insecurity was greater than for personal job insecurity. Perhaps this was due to media coverage of the economic threats of the pandemic. It will be valuable for future research to examine sources of perceptions of national job insecurity.

Our overall findings were largely replicated when examining data for each country separately. To some extent, this finding is quite remarkable given the many ways in which these countries differ (e.g., labor practices, welfare regimes, economic conditions and events, political systems). One could wonder whether individual perceptions of the state differ depending on the economic-political regime and their experiences within it. According to the OECD, in response to the pandemic there were about 10 times more job retention schemes in place across OECD nations than during the 2008/2009 crisis (Scarpetta et al., 2020). Particularly novel were these schemes in more liberal economies (such the US and UK), where people understood them as essential to protect livelihoods and careers (82% agreement; Duffy et al., 2021). It would be interesting to find out whether a novel introduction of job retention schemes (and other social protective measures) lead to a change in attitudes towards equality, trust in the government, or even political thinking more so than when workers are already familiar with worker protection schemes. Our study does not allow us to investigate this question, but future research taking large national longitudinal surveys as their database might provide more information. Similarly, it would be interesting to compare how these responses might change in events that are solely financial (e.g., another recession) as compared to the COVID-19 pandemic, which also has a health disaster element. Economic recessions are typically associated with zero-sum thinking, which may lead people to be more concerned with their own interests than those of society (Shoss et al., 2021; Sirola and Pitesa, 2017). Yet, perceptions that worries about jobs are widespread may fuel movements to promote change in systems that have led to these problems (e.g., the 99% movement in the United States during the Great Recession).

Together, these findings provide a psychological foundation for understanding how people’s views about the security of jobs (their own and others) are linked to their views about government and other people in their society. This psychological foundation suggests that it is useful to distinguish individuals’ views of the security of their own work from their perceptions about what others in society experience. Interestingly, it is the latter that seems most important for societal outcomes. These findings may help political scientists and others to refine theories on how elements of work relate to how individuals view society’s institutions and members.

Our findings complement efforts that have sought to examine individual and shared perceptions of job insecurity (Låstad et al., 2018). Job insecurity research, especially when seeking to understand reactions to major widespread employment shocks, may benefit from also considering perceptions of the widespread nature of job insecurity in addition to established constructs such as individual perceptions of job insecurity. Past research has suggested that individuals develop perceptions of personal job insecurity in part based on their perceptions of the broader macro-environmental forces (Jacobson and Hartley, 1991; Koen and Parker, 2020; Lee et al., 2017). If this is the case, what is remaining in personal job insecurity when accounting for perceived national job insecurity may reflect threats unique to the individual (e.g., threats linked to their own performance or own circumstances; Carusone et al., 2021), which our findings suggest might have less relevance for societally- and governmentally-directed outcomes.

Implications for practice

The lessons to be learned for governments and policy makers from this study indicate a double-edged sword. On the one hand, governments are more likely to be evaluated as doing their job badly during periods of high perceived national job insecurity, which might even lead to a regime change (see e.g., Lewis-Beck and Whitten, 2013). On the other hand, when it comes to attitudes and behavior towards fellow citizens, high national job insecurity can have positive effects. Rather than pushing people away from each other, the perception of other citizens’ suffering from job insecurity actually predicted the opposite: it was associated with more societal solidarity and a greater willingness to adhere to measures to protect the health of others and likely, by extension, to be protected by others who presumably should also react this way. This qualifies propositions by others, that labor-flexibility would create a ‘dog eat dog’ world of disenfranchisement (e.g., Standing, 2020). This study shows that if this sentiment is perceived to be shared widely, rather more solidarity might be the case. This is reminiscent of the concept of shared fate during times of disasters: because of the pandemic, job insecurity might have acted as yet another societal hardship. These findings are particularly interesting considering research from earlier in the pandemic that linked personal job insecurity to personal hygiene COVID-recommendations (Probst et al., 2020). As businesses open up and social behavior becomes particularly important, compliance may be more related to perceptions of one’s social environment than individuals’ own job risks.

Limitations and future directions

This study is limited in several ways. That our sample overrepresented higher skilled workers, although a classical finding for similar surveys, might have affected our results as there is evidence suggesting that job insecurity may be more prevalent among blue collar workers (Keim et al., 2014). Consequently, some associations might be lower here than in the population, possibly leading to reduced correlations for personal job insecurity.

Second, although one might be concerned about potential social desirability with regard to COVID-19 compliance, recent research suggests that potential social desirability bias for these types of questions is minor (Jensen, 2020). However, future research may seek out various objective indicators (e.g., how layoffs/the economy are being portrayed in various news outlets, objective COVID-19 spread, voter polls, etc.). Finally, we used a single item for satisfaction with the government’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis. While single items are preferable when seeking to capture holistic preferences (Drolet and Morrison, 2001; Nagy, 2002), future research may seek to explore this construct further.

We encourage future work on people’s perceptions of their social environments, both within the job insecurity literature and beyond. Within the realm of job insecurity, researchers might examine people’s perceptions of the prevalence of job insecurity within their organizations, communities, or groups as predictors of meaningful outcomes with reference to each. Given the variability in perceptions of job insecurity found here, research may seek to understand the sources of variation in perceived national job insecurity and expand its nomological net. Additionally, the mechanism behind our findings warrants more exploration: it is possible that perception of work-relevant phenomena on a national level makes the national collective salient in an individual’s personal identity structure (Turner et al., 1994). In that regard it might trigger other collectively relevant sentiments, such as perception of oneself as a proud (or not so proud) member of that collective, and associated attitudes.

Research may also seek to examine other domains of perceptions of one’s social environment to see if similar findings emerge. For example, perceptions of what fellow citizens earn, how safe jobs should be, what acceptable behavior at work is, might have far reaching implications for how people see their own work. Indeed, future studies might investigate broader perceptions of work-related phenomena, and their role in how people see themselves and their place in society. Work along these lines has already begun in the area of subjective income inequality. Schmalor and Heine (2021) recently found that subjective inequality predicts well-being and trust over the effects of one’s perceived social status and political orientation. Thus, it seems that people’s perceptions of their environments are important variables deserving of future research.

Our findings along with larger societal discussions about jobs stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that future research on broader societal consequences of job insecurity is warranted. For example, there is limited literature that speaks of the impact of job insecurity on social attitudes and behaviors, such as voting behaviors and the attitudinal antecedents of voting, or on the attitudes towards politics, society, and trust in leadership (Van Hootegem et al., 2021; Wroe, 2014, 2016). Research might also examine the consequences of entering the workforce when one perceives there to be great prevalence of job insecurity, similar to research on economic conditions at workforce entry (Bianchi, 2013), and the long-arm impacts of perceived national job insecurity, similar to work on the impact of parental job insecurity on children’s attitudes and behaviors (Zhao et al., 2012).

Conclusions

In summary, our findings from three countries suggest that the perception of job insecurity as widespread in one’s country during the COVID-19 crisis is associated with how individuals react towards their government and to others in society. While those who have higher as opposed to lower perceived national job insecurity tend to view their government as breaching the psychological contract and poorly managing the pandemic, they also tend to express more solidarity towards others and to take more precautions to protect others from the virus.

Author biographies

Mindy Shoss is Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Central Florida and Honorary Professor at the Australian Catholic University. Her research takes a psychological approach to understanding the relationships between work (i.e., quality, conditions, organization of work), well-being, and behavior. Recent publications address job insecurity, counterproductive work behaviors, and the future of work.

Anahí Van Hootegem is currently working at KU Leuven, Belgium. Her research in work psychology focuses on job insecurity and how this affects positive outcomes such as innovative work behavior and work-related learning, as well as the wider societal and political consequences of job insecurity.

Eva Selenko is a senior lecturer in work psychology at Loughborough University, UK. She has published widely on job insecurity, precarious work and how this affects well-being, work behavior and how people see themselves and others. With her research she hopes to stimulate new thinking about the social consequences of precarious work.

Hans De Witte is Full Professor in Work Psychology at the Research Group Work, Organizational and Personnel Psychology of the KU Leuven (Belgium), and is Extraordinary Professor at the North-West University of South Africa (Optentia Research Unit). He studies the psychological consequences of job insecurity and unemployment, as well as burnout versus work engagement.

We also examined controlling for several demographic factors that we found to be correlated with one or more outcomes: gender, occupation, politics, and work hours. The results remained largely unchanged, except that the non-significant relationship between personal job insecurity and government satisfaction became significant. Given concerns over the use of control variables in organizational research (Becker et al., 2016), our results here are presented without controls.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Mindy Shoss  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5354-208X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5354-208X

Anahí Van Hootegem  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5479-3347

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5479-3347

Eva Selenko  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9579-9200

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9579-9200

Contributor Information

Mindy Shoss, University of Central Florida, USA; Australian Catholic University, Australia.

Anahí Van Hootegem, O2L, KU Leuven, Belgium.

Eva Selenko, Loughborough University, UK.

Hans De Witte, O2L, KU Leuven, Belgium; Optentia Research Unit, North-West University, South Africa.

References

- Abadie A, Athey S, Imbens GW, Wooldridge J. (2017) When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? Working Paper.

- Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. (2000) Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychology 19(6): 586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkermans J, Richardson J, Kraimer M. (2020) The Covid-19 crisis as a career shock: Implications for careers and vocational behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior. Epub ahead of print June 2020. 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Becker TE, Atinc G, Breaugh JA, et al. (2016) Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. Journal of Organizational Behavior 37(2): 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Bendau A, Petzold MB, Pyrkosch L, et al. (2021) Associations between COVID-19 related media consumption and symptoms of anxiety, depression and COVID-19 related fear in the general population in Germany. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 271: 283–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi EC. (2013) The bright side of bad times: The affective advantages of entering the workforce in a recession. Administrative Science Quarterly 58(4): 587–623. [Google Scholar]

- Billiet J, Meuleman B, De Witte H. (2014) The relationship between ethnic threat and economic insecurity in times of economic crisis: Analysis of European Social Survey data. Migration Studies 2(2): 135–161. 10.1093/migration/mnu023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell M, Iacus S, King G, Porro G. (2009) Cem: Coarsened exact matching in Stata. The Stata Journal 9(4): 524–546. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AD, Colville I, Pye A. (2015) Making sense of sensemaking in organization studies. Organization Studies 36(2): 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP. (2001) Perceived superiority of one’s own relationship and perceived prevalence of happy and unhappy relationships. British Journal of Social Psychology 40(4): 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buunk AP, Gibbons FX. (2007) Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 102(1): 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Van den Eijnden RJJM. (1997) Perceived prevalence, perceived superiority, and relationship satisfaction: Most relationships are good, but ours is the best. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 23: 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Oldersma FL, De Dreu CK. (2001) Enhancing satisfaction through downward comparison: The role of relational discontent and individual differences in social comparison orientation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 37(6): 452–467. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona C, Buunk AP, Peiró JM, et al. (2006) Do social comparison and coping styles play a role in the development of burnout? Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 79(1): 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Carusone N, Pittman R, Shoss MK. (2021) Sometimes it’s personal: Differential outcomes of person vs job at risk threats to job security. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (Special Issue on ‘Job Insecurity and Precarious Employment as Psychosocial Risk Factors in Contemporary Society’) 18(14): 7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FF. (2007) Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14(3): 464–504. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. (2002) Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling 9(2): 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming DJ, Wood G, Zahra SA. (2020) Human resource management practices in the context of rising right-wing populism. Human Resource Management Journal. Epub ahead of print 3 February 2020. 10.1111/1748-8583.12269 [DOI]

- De Witte H. (1999) Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 8(2): 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte H. (2000) Arbeidsethos en jobonzekerhed: meting en gevolgen voor welzijn, tevredenheid en inzet op het werk [Work ethic and job insecurity: Assessment and consequences for well-being, satisfaction and performance at work]. In: Bouwen R, De Witte K, Tailleu T. (eds) Van groep naar gemeenschap. [From Group to Community] Liber Amicorum Prof. Dr. Leo Lagrou. Leuven: Garant, pp. 325–350. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker F. (2010) Labour flexibility, risks and the welfare state. Economic and Industrial Democracy 31(4): 593–611. 10.1177/0143831x10365927 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet Al, Morrison DG. (2001) Do we really need multiple-item measures in service research? Journal of Service Research 3(3): 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Drury J, Reicher S, Stott C. (2020) COVID-19 in context: Why do people die in emergencies? It’s probably not because of collective psychology. British Journal of Social Psychology 59(3): 686–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy B, Hewlett K, Hesketh R, et al. (2021) Unequal Britain: Attitudes to inequalities after Covid-19. London: King’s College London. [Google Scholar]

- Elcheroth G, Drury J. (2020) Collective resilience in times of crisis: Lessons from the literature for socially effective responses to the pandemic. British Journal of Social Psychology 59(3): 703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmenegger P, Marx P, Schraff D. (2015) Labour market disadvantage, political orientations and voting: How adverse labour market experiences translate into electoral behaviour. Socio-Economic Review 13(2): 189–213. [Google Scholar]

- European Social Survey (2018) 10.21338/NSD-ESS-CUMULATIVE [DOI]

- Gough JW. (1978) The Social Contract: A Critical Study of its Development. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- GOVTRUST Centre of Excellence University of Antwerp (2020) Trust in COVID-19 government policies. Available at: https://medialibrary.uantwerpen.be/oldcontent/container57464/files/Corona-English.pdf?_ga=2.138132976.1539034894.1613987165-889554523.1613987165

- Green F. (2011) Unpacking the misery multiplier: How employability modifies the impacts of unemployment and job insecurity on life satisfaction and mental health. Journal of Health Economics 30(2): 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hällgren M, Rouleau L, De Rond M. (2018) A matter of life or death: How extreme context research matters for management and organization studies. Academy of Management Annals 12(1): 111–153. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington D. (2009) Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley J, Jacobson D, Klandermans B, Van Vuuren T. (eds) (1991) Job Insecurity: Coping with Jobs at Risk. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Haugsgjerd A, Kumlin S. (2020) Downbound spiral? Economic grievances, perceived social protection and political distrust. West European Politics 43(4): 969–990. [Google Scholar]

- HM Treasury (2021) £4.6 billion in new lockdown grants to support businesses and protect jobs. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/news/46-billion-in-new-lockdown-grants-to-support-businesses-and-protect-jobs

- ILO (International Labour Organization) (2020) ILO: As job losses escalate, nearly half of global workforce at risk of losing livelihoods. Available at: www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_743036/lang–en/index.htm

- Jacobson D, Hartley J. (1991) Mapping the context. In: Hartley J, Jacobson D, Klandermans B, Van Vuuren T. (eds) Job Insecurity: Coping with Jobs at Risk. London: Sage, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen UT. (2020) Is self-reported social distancing susceptible to social desirability bias? Using the crosswise model to elicit sensitive behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration 3(2). [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T, Dawes C, Fowler J, Smirnov O. (2020) Slowing COVID-19 transmission as a social dilemma: Lessons for government officials from interdisciplinary research on cooperation. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration 3(1). [Google Scholar]

- Keim AC, Landis RS, Pierce CA, Earnest DR. (2014) Why do employees worry about their jobs? A meta-analytic review of predictors of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 19(3): 269–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koen J, Parker SK. (2020) In the eye of the beholder: How proactive coping alters perceptions of insecurity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 25(6): 385–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger J. (1998) On the perception of social consensus. In: Zanna MP. (ed.) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 30. London: Academic Press, pp. 163–240. [Google Scholar]

- Låstad L, Berntson E, Näswall K, et al. (2015) Measuring quantitative and qualitative aspects of the job insecurity climate: Scale validation. Career Development International 20(3): 202–217. [Google Scholar]

- Låstad L, Näswall K, Berntson E, et al. (2018) The roles of shared perceptions of individual job insecurity and job insecurity climate for work- and health-related outcomes: A multilevel approach. Economic and Industrial Democracy 39(3): 422–438. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Huang G-H, Ashford SJ. (2017) Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Beck MS, Whitten GD. (2013) Economics and elections: Effects deep and wide. Electoral Studies 32(3): 393–395. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. (2013) Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lübke C, Erlinghagen M. (2014) Self-perceived job insecurity across Europe over time: Does changing context matter? Journal of European Social Policy 24(4): 319–336. [Google Scholar]

- Méda D. (2019) Three scenarios for the future of work. International Labour Review 158(4): 627–652. [Google Scholar]

- Morin AJS, Meyer JP, Creusier J, Biétry F. (2016) Multiple-group analysis of similarity in latent profile solutions. Organizational Research Methods 19(2): 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison EW, Robinson SL. (1997) When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review 22(1): 226–256. [Google Scholar]

- Mughan A, Bean C, McAllister I. (2003) Economic globalization, job insecurity and the populist reaction. Electoral Studies 22(4): 617–633. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. (1998. –2017) Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy MS. (2002) Using a single-item approach to measure facet job satisfaction. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 75(1): 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nivette A, Ribeaud D, Murray AL, et al. (2020) Non-compliance with COVID-19-related public health measures among young adults: Insights from a longitudinal cohort study. Social Science & Medicine 268: 113370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North DC. (1991) Institutions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 5(1): 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Pesqueux Y. (2012) Social contract and psychological contract: a comparison. Society and Business Review 7(1): 14–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pfattheicher S, Nockur L, Böhm R, et al. (2020) The emotional path to action: Empathy promotes physical distancing and wearing of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Science 31(11): 1363–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst TM, Lee HJ, Bazzoli A. (2020) Economic stressors and the enactment of CDC-recommended COVID-19 prevention behaviors: The impact of state-level context. Journal of Applied Psychology 105(12): 1397–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SL, Morrison EW. (2000) The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior 21(5): 525–546. [Google Scholar]

- Rodger JJ. (2003) Social solidarity, welfare and post-emotionalism. Journal of Social Policy 32(3): 403–421. [Google Scholar]

- Roehling MV. (1997) The origins and early development of the psychological contract construct. Journal of Management History 3(2): 204–217. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph CW, Allan B, Clark M, et al. (2021) COVID-19: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Research and Practice 14(1–2): 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg J, Tsoukas H. (2015) Making sense of the sensemaking perspective: Its constituents, limitations, and opportunities for further development. Journal of Organizational Behavior 36(S1): S6–S32. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpetta S, Pearson M, Hijzen A, Salvatori A. (2020) Job retention schemes during the COVID-19 lockdown and beyond. OECD, 12October. Available at: www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/job-retention-schemes-during-the-covid-19-lockdown-and-beyond-0853ba1d/#abstract-d1e26

- Schmalor A, Heine SJ. (2021) The construct of subjective economic inequality. Social Psychological and Personality Science. Epub ahead of print 9 March 2021. 10.1177/1948550621996867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Selenko E, De Witte H. (2020) How job insecurity affects political attitudes: Identity threat plays a role. Applied Psychology 70(3): 1267–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett R. (1998) The Corrosion of Character: The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Shoss MK. (2017) Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management 43(6): 1911–1939. [Google Scholar]

- Shoss MK, Horan KA, DiStaso M, et al. (2021) The conflicting impact of COVID-19’s health and economic crises on helping. Group & Organization Management 46(1): 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shoss MK, Jiang L, Probst TM. (2018) Bending without breaking: A two-study examination of employee resilience in the face of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 23(1): 112–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair RR, Allen T, Barber L, et al. (2020) Occupational health science in the time of COVID-19: Now more than ever. Occupational Health Science 4(1): 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirola N, Pitesa M. (2017) Economic downturns undermine workplace helping by promoting a zero-sum construal of success. Academy of Management Journal 60(4): 1339–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Standing G. (2020) Battling Eight Giants: Basic Income Now. London: IB Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Sverke M, Låstad L, Hellgren J, et al. (2019) A meta-analysis of job insecurity and employee performance: Testing temporal aspects, rating source, welfare regime, and union density as moderators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Oakes PJ, Haslam SA, McGarty C. (1994) Self and collective: Cognition and social context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20(5): 454–463. [Google Scholar]

- Unite (2020) Covid-19: Confusion for workers and lack of financial support at odds with national emergency, McCluskey tells PM. Available at: https://unitetheunion.org/news-events/news/2020/march/covid-19-confusion-for-workers-and-lack-of-financial-support-at-odds-with-national-emergency-mccluskey-tells-pm/

- Vander Elst T, De Witte H, De Cuyper N. (2014) The job insecurity scale: A psychometric evaluation across five European countries. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 23(3): 364–380. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hootegem A, Van Hootegem A, Selenko E, De Witte H. (2021) Work is political: Distributive injustice as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between job insecurity and political cynicism. Political Psychology. Epub ahead of print 26 May 2021. 10.1111/pops.12766 [DOI]

- Van Oorschot W. (2006) Making the difference in social Europe: Deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy 16(1): 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE. (1995) Sensemaking in Organizations. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE, Sutcliff KM, Obstfeld D. (2005) Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science 16(4): 327–451. [Google Scholar]

- Wroe A. (2014) Political trust and job insecurity in 18 European polities. Journal of Trust Research, 4(2): 90–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wroe A. (2016) Economic insecurity and political trust in the United States. American Politics Research 44(1): 131–163. [Google Scholar]