Abstract

Strong evidence indicates critical roles of NADPH oxidase (a key superoxide-producing enzyme complex during inflammation) in activated microglia for mediating neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. However, little is known about roles of neuronal NADPH oxidase in neurodegenerative diseases. This study aimed to investigate expression patterns, regulatory mechanisms and pathological roles of neuronal NADPH oxidase in inflammation-associated neurodegeneration. The results showed persistent upregulation of NOX2 (gp91phox; the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase) in both microglia and neurons in a chronic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease (PD) with intraperitoneal LPS injection and LPS-treated midbrain neuron-glia cultures (a cellular model of PD). Notably, NOX2 was found for the first time to exhibit a progressive and persistent upregulation in neurons during chronic neuroinflammation. While primary neurons and N27 neuronal cells displayed basal expression of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4, significant upregulation only occurred in NOX2 but not NOX1 or NOX4 under inflammatory conditions. Persistent NOX2 upregulation was associated with functional outcomes of oxidative stress including increased ROS production and lipid peroxidation. Neuronal NOX2 activation displayed membrane translocation of cytosolic p47phox subunit and was inhibited by apocynin and diphenyleneiodonium chloride (two widely-used NADPH oxidase inhibitors). Importantly, neuronal ROS production, mitochondrial dysfunction and degeneration induced by inflammatory mediators in microglia-derived conditional medium were blocked by pharmacological inhibition of neuronal NOX2. Furthermore, specific deletion of neuronal NOX2 prevented LPS-elicited dopaminergic neurodegeneration in neuron-microglia co-cultures separately grown in the transwell system. The attenuation of inflammation-elicited upregulation of NOX2 in neuron-enriched and neuron-glia cultures by ROS scavenger N-acetylcysteine indicated a positive feedback mechanism between excessive ROS production and NOX2 upregulation. Collectively, our findings uncovered crucial contribution of neuronal NOX2 upregulation and activation to chronic neuroinflammation and inflammation-related neurodegeneration. This study reinforced the importance of developing NADPH oxidase-targeting therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Neuronal NADPH oxidase, NOX2, Microglia, Oxidative stress, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

Chronic neuroinflammation especially over-activation of microglia is a common feature shared by all neurodegenerative diseases and has been incriminated as a major contributor to neurodegeneration in various neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1–4]. Neuroinflammation is known to implement both beneficial and detrimental effects in the brain, depending on whether the acute inflammation can be effectively resolved [5, 6]. If the inflammation resolution is not well executed, lingering low-grade chronic neuroinflammation will continue and eventually lead to progressive neurodegeneration [7]. Mechanisms behind the pathological transition from acute to chronic neuroinflammation remain unclear. Emerging evidence supports the notion that oxidative stress and chronic neuroinflammation are intertwined key pathologic factors in neurodegenerative diseases. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by activated microglia during chronic neuroinflammation has been demonstrated to be one of the major mediators of progressive neuronal loss [8, 9].

NADPH oxidase, a membrane-bound, multi-subunit enzyme complex, is a major superoxide-producing enzyme during inflammation. Increased activity of NADPH oxidase on microglia has been shown to play a key role in the pathogenesis of several chronic neurodegenerative disorders, such as AD and PD [10–12]. Extensive studies have focused on the roles of microglial NADPH oxidase in physiological and pathological conditions. It is well-documented that upon activation, cytosolic subunits of phagocyte NADPH oxidase (i.e., p40phox, p47phox and p67phox) translocate to the cell membrane and bind to membrane-bound subunits (p22phox/gp91phox). NOX2, also known as gp91phox, is the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase. Activated NOX2 catalyzes the transfer of the electron from NADPH to molecular oxygen resulting in the production of superoxide radical anion. Over-activated or dysregulated microglial NADPH oxidase produces excessive superoxide radical and causes oxidative damage, leading to neurodegeneration [10, 13–15]. Furthermore, post-mortem studies have revealed increased mRNA transcript of NOX2 in various brain regions of AD and PD patients [16–18]. The substantia nigra (SN) of patients and mouse models of PD showed high levels of NOX2, which is accompanied by chronic neuroinflammation markers [3, 18]. Superoxide radical, generated by upregulated microglial NADPH oxidase, instigates nigral dopaminergic neurodegeneration and formation of α-synuclein-containing Lewy bodies in PD [19].

Compared with microglial NADPH oxidase, little is known regarding regulation and pathophysiological roles of neuronal NADPH oxidase in neurodegenerative diseases [12]. Acute pathological consequences of short-term activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase by NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartic acid; a synthetic agonist of NMDA receptor) have been reported. NMDA triggers a rapid elevation in superoxide radical and neuronal death in cultured neurons and mouse hippocampal neurons. Such events are prevented by NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin or deletion of p47phox, the subunit required for NADPH oxidase assembly and activation. NADPH oxidase, but not the mitochondrion, is the primary source of NMDA-induced superoxide generation in neurons [20]. Social isolation for 2–4 weeks in rats causes NOX2 upregulation in the brain, in which pyramidal neurons display more profound NOX2 upregulation than GABAergic neurons, astrocytes and microglia. Administration of apocynin in drinking water or a loss-of-function mutation of p47phox prevents neuropathology induced by social isolation [21]. These findings indicate important contribution of increased activity of NADPH oxidase to psychosocial stress-induced neuropathology and also hint at possible involvement of neuronal NOX2. Moreover, it is reported that NOX2-related oxidative stress contributes to neuropathic pain through promoting membrane translocation of PKCε in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons [22]. NOX2 overexpression in dorsal root ganglion neurons promotes regeneration of sensory axons and functional recovery after spinal cord injury [23]. Up to date, roles of neuronal NADPH oxidase in chronic neurodegeneration especially inflammation-related chronic neurodegeneration remain to be investigated.

The present study characterized expression patterns of different isoforms of NOX in neurons with or without exposure to inflammatory mediators and delineated neuronal NOX2 activation mechanisms using a transwell culture system. We further investigated molecular mechanisms underlying the persistent upregulation of NOX2 during chronic neuroinflammation. This study also determined roles of neuronal NOX2 in mediating chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

The wildtype (WT) mice (C57BL/6J), B6.129S6-Cybbtm1Din/J (NOX2−/−; gp91phox−/−) mice, and timed-pregnant Fisher F344 rats were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). WT mice were received an intraperitoneal injection of saline or LPS (5 mg/kg; 15 × 106 EU/kg). At 24 hours later, mice were sacrificed and their brains were collected. Housing, dosing and breeding of animals were performed humanely following the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources). All procedures were approved by the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell cultures

Primary midbrain neuron-glia and neuron-enriched cultures were prepared from the ventral mesencephalon of embryos (E14) from time-pregnant Fischer 334 rats as well as NOX2−/− and WT mice. Mechanically dissociated cells were seeded into poly-D-lysine-coated (20 μg/ml) 24-well (6–8 × 105 cells/well) plates and maintained in MEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% heat-inactivated horse serum (HS), 1 g/l glucose, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids. Seven-day-old cell cultures were then treated with vehicle or desirable reagents in the treatment medium (MEM containing 2% FBS, 2% HS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate). At the time of treatment, the neuron-glia cultures were made up of ~13% ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1)-immunoreactive (IR) microglia, 48% glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-IR astrocytes, and 39% neuron-specific nuclear protein (Neu-N)-IR neurons of which 2.5–3.5% were tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-IR dopamine neurons [13, 24]. Because microglia, astroglia and neurons have been reported to express NOX2 and other isoforms, in order to generate neuron-enriched cultures with minimal contamination of microglia and astroglia, we modified and optimized our previous protocol for preparation of neuron-enriched cultures [13, 24] and significantly improved the purity of neuron-enriched cultures. Instead of one-time addition, cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside (Ara-C) was added to the cultures twice: two days (5 or 10 μM) and four days (2.5 or 5 μM) after initial seeding of mechanically dissociated midbrain cells to better suppress the proliferation of glial cells. The 6-day-old neuron-enriched cultures were used for treatment, measurement or preparation of the reconstituted neuron-microglia co-cultures. Immunostaining of markers of neurons (Neu-N), microglia (CD11b and Iba1) and astroglia (GFAP), ELISA measurement of LPS-triggered TNFα secretion, and Q-PCR assay of CD11b and GFAP with or without inflammatory stimulation indicated a very high purity of the neuron-enriched cultures with negligible contamination of microglia (< 0.1%) or astroglia (< 0.5%) (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Mixed-glia cultures and microglia-enriched cultures.

Mixed-glia cultures were prepared from whole brains of postnatal day 1 mouse pups [25]. Disassociated brain cells were seeded into 96-well plates (105 cells/well) or 175 cm2 flasks (3 brains/flask) and maintained in 100 μl/well or 20 ml/flask DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids. The medium was changed every 3 days. When reaching confluence at 11–12 d after plating, the mixed-glia cultures contained ~80% GFAP-IR astrocytes and ~20% Iba-1-IR microglia and were used for treatment or preparation of enriched microglia. Microglia were isolated by shaking the flasks containing confluent mixed-glia cultures for 1 h at 150 rpm. The enriched microglia were greater than 98% pure as determined by immunostaining for microglia- and astrocyte-specific markers Iba1 and GFAP, respectively [24, 26].

Reconstituted neuron-microglia co-cultures in transwell culture systems.

The midbrain neuron-enriched cultures were first prepared in regular 24-well culture plates as described above. Six days after the initial seeding, the cultures were changed to fresh neuron-glia treatment medium. Highly enriched microglia (5 × 104/well) were plated into transwell inserts (HTS multi-well insert systems, 1.0 μm pore size, PET membrane, BD Sciences, San Jose, CA) placed above the neuron layer. Although there was no physical contact between microglia and neurons, secreted soluble factors could move across the transwell membranes [14].

Real time Q-PCR.

Isolation of total RNA from the cell pellets was performed by using TRIzol according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Quality and quantity of total RNA were examined by using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Reverse transcriptase reactions were run on 1 μg of total messenger RNA (mRNA) by using the reverse transcription system (Promega, Madison, WI). Q-PCR was performed by using a Light Cycler 480 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and the SYBR Green I Master (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunocytochemistry.

Immunostaining was performed as described previously [26] with antibodies specific for NOX2 (gp91phox; BD Biosciences; 1:1000) or TH (Millipore; 1:5000). Briefly, formaldehyde-fixed cell cultures were blocked with appropriate normal serum followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with a primary antibody diluted in antibody diluent solution (Dako). After incubation with an appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody and then the Vectastain ABC reagents (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA, USA), the bound complex was visualized by color development with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB). Images were recorded with a CCD camera and the ZEN 2.3 lite software (Molecular Devices).

Immunofluorescence.

To determine cell type(s) of the upregulated NOX2 post LPS treatment, neuron-glia cultures grown on glass chamber or brain slices (16 μM in thickness) were co-stained with NOX2 and either microglia marker or neuronal marker. After blocking with PBS containing 5% goat serum and 0.3% Triton-X, the cells were immune-stained for gp91phox (BD Biosciences; 1:500) and Iba1 (Wako Pure Chemicals; 1:2500), Nissl or microfilament-associated protein-2 (MAP-2; a widely-used neuron-specific protein marker with a function of microtubule stabilization in dendrites of postmitotic neurons; Chemicon; 1:1000). All images were collected and analyzed using a Zeiss LSM 780 or 880 confocal microscope.

Quantification of NOX2 fluorescent intensity of confocal fluorescent images with ImageJ.

Fluorescent images, acquired by using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope, were split and saved as single channel images with ZEN 2.3 lite software (Molecular Devices). Integrated fluorescent intensity of overall NOX2 (red channel) was measured and calculated by ImageJ software. The threshold was set to 30 and 255 for measurements, respectively. For each mouse, 4 representative images were obtained, and 5 mice per group were quantified. For measurement of neuronal NOX2 and microglial NOX2, neurons and microglia with MAP-2 (green) and Iba1 (pink) staining and distinct cellular morphology of neurons and microglia were selected for the subset images with “Region of Interest (ROI)” in ZEN 2.3 lite software. The resulting subset images were used for quantification of fluorescent intensity of neuronal and microglia NOX2 (red channel) with the same method described above for the measurement of fluorescent intensity of the overall NOX2. Twenty representative neurons or microglia per mice were obtained and 5 mice per group were quantified by an individual blind to the treatment.

[3H]dopamine uptake assay.

The uptake assay was performed as described [26]. Briefly, after rinsing twice with warm Krebs–Ringer buffer (KRB, 16 mm sodium phosphate, 119 mm NaCl, 4.7 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1.3 mm EDTA, and 5.6 mm glucose; pH 7.4), the cultures were incubated for 20 min at 37°C with 1 μM [3H]dopamine (30 Ci/mmol, NEN, Boston, MA, USA) in KRB. After washing three times with ice-cold KRB, cells were solubilized in 1M NaOH, and radioactivity was counted with a liquid scintillation counter. Nonspecific uptake was determined in the additional presence of 20 μM GBR 12935 dihydrochloride (S9659, Sigma), which is a dopamine transporter inhibitor.

Western blotting.

Whole cell proteins were extracted from cultured cells in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitor cocktail) and heated to 95°C for 10 min. Protein concentrations were determined using the biocinchoninic acid assay (BCA, ThermoFisher). Protein samples were resolved on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (life technologies), and immunoblot analyses were performed using antibodies against gp91phox (BD Biosciences, 1:1000) and p67phox (Cell Signaling, 1:1000). An antibody against β-actin or GAPDH (Cell Signaling, 1:5000) was included to monitor loading errors.

Membrane fractionation.

Midbrain neuron-microglia co-cultures in transwell systems were treated with vehicle or LPS (10 ng/ml; the concentration used in all in vitro experiments unless otherwise indicated) for 30 min, and then neuronal cells were collected and separated into membrane and cytosol fractions as previously described [14, 27]. Briefly, neurons were lysed in hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.32 M sucrose, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor cocktail) on ice for 30 min. After Dounce homogenization, membrane and cytosolic fractions were collected separately by differential centrifugation: the lysates were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to remove unbroken cells, cell debris, and nuclei; the supernatants were centrifuged at 185,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C to separate the total membrane fraction from all soluble proteins. The pellets were washed once, followed by the high-speed sedimentation. The membrane fraction was generated by solubilization of pellets in the TNE buffer. Western blotting analysis was then used to detect the distribution of p47phox (Millipore, 1:1000) in membrane and cytosol, respectively.

Measurement of intracellular ATP.

ATP content was determined using a bioluminescence assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO). Pretreated cells were washed in PBS twice and lysed in buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) on ice for 10 min. After removal of cell debris by centrifugation (10,000 × g) for 15 min at 4°C, the ATP content was measured by the luciferin/luciferase method [28]. The absolute value of ATP content was determined using an internal ATP standard.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential.

Mitochondrial membrane potential was determined using JC-1 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), a mitochondrial-specific fluorescent probe. JC-1 exists as a green-fluorescent monomer at low membrane potential (< 120 mV) and as a red-fluorescent dimer (J-aggregates) when the membrane potential is greater than 180 mV. Following excitation at 485 nm, the ratio of red (595 nm emission) to green (525 nm emission) fluorescence represents the relative mitochondrial membrane potential. Treated neuron-enriched cultures were incubated in 0.5 ml of PBS containing 10 μg/ml JC-1 at 37°C for 10 min, and the fluorescence intensity was read at 488 nm for excitation and 525/595 nm for emission using a fluorescence microplate reader. The ratio of A595:A525 was calculated as an indicator of mitochondrial potential [29].

Measurement of intracellular ROS (iROS).

iROS was measured by the cell-permeable fluorescence probe 2ʹ,7ʹ-Dichlorofluorescin Diacetate (H2DCFDA; Calbiochem; Cat# 287810) as described [15]. The reagent passively enters cells where it is de-acetylated by cellular esterase to non-fluorescent DCFH. Inside the cell, DCFH is oxidized to form high-fluorescent DCF (the final fluorescent product). The limitation of H2DCFDA is that it cannot be used to reliably detect a specific species of oxidants, although it has been claimed to measure H2O2 sometimes. In fact, DCFH does not directly react with H2O2; instead, iron-catalyzed reaction of H2O2 leads to formation of DCF.− that reacts with dioxygen to form superoxide; superoxide is dismuted immediately by superoxide dismutase to form H2O2 that is converted to H2O by catalase catalyzing [30]. Neuron-enriched cultures exposed to microglia-derived conditional medium (CM) for 24 hours were incubated with H2DCFDA (10 μM) for 30 min at 37°C and then washed with PBS. The fluorescence intensity was read at 488 nm for excitation and 525 nm for emission using a SpectraMax Gemini XS fluorescence microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Because detection of DCF fluorescence by microplate readers is less sensitive than microscopes and exhibits far less signal-to-background difference, neuron-enriched cultures grown in glass chambers were exposed to microglia-derived CM for 24 hours and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 10 μM CM-H2DCFDA (chloromethyl-29, 79-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; a chloromethyl derivative of H2DCFDA with much better retention in live cells than H2DCFDA; Invitrogen; Cat# C6827). After the cultures were washed twice with PBS, fluorescent images were collected using Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope and analyzed by using ImageJ software.

Detection of Dihydroethidium (DHE).

DHE is a cell-permeable fluorescence probe that is converted to superoxide-specific product 2-hydroxyethidium and superoxide-independent product ethidium in live cells. These two fluorescent products shared overlapped fluorescence emission. The oxidation of DHE has been used to examine iROS production and cellular oxidative stress in situ. At 1, 8 and 18 months after intraperitoneal LPS/vehicle injection, the mice were injected with DHE (30 mg/kg, intraperitoneal). Mouse brains were harvested 30 minutes after DHE injection. SN-containing coronal cryosections of mouse brains were immunostained for TH. Fluorescent images of nigral dopamine neurons with double-labeling of ethidium/2-hydroxyethidium (red) and TH (green) were collected using Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope.

Measurement of lipid peroxidation.

Lipid peroxidation was determined in brain homogenates through the measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA; an end product of lipid peroxidation) as described [31]. After mice were sacrificed by decapitation, their brains were rapidly excised, washed with chilled normal saline, blotted dry and weighed. Tissue homogenates (1:10; w/v) of the brain were prepared on ice by using Dounce homogenizer in the buffer containing 250 mM sucrose supplemented with 0.12 mM dithiothreitol buffered with 20 mM triethanolamine hydrochloride buffer, pH 7.4. Crude brain homogenates were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris and nuclei. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 85,000 × g for 45 min at 4°C, and the supernatant fraction (i.e., the brain homogenate) was collected and used to measure MDA. The amount of MDA was measured spectrophotometrically at 532 nm after its reaction with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) to form a colorimetric product.

Statistical analysis.

All values were expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences among means were analyzed using one or two-way ANOVA with treatment as the independent factors. When ANOVA showed significant differences, multiple or pair-wise comparisons between means were tested by Turkey, Sidak’s or Newman-Keuls post-hoc testing. In all analyses, the null hypothesis was rejected at the 0.05 level.

Results

NOX2 was persistently upregulated in microglia and neurons under inflammatory conditions

Immune factors responsible for the formation and the maintenance of chronic neuroinflammation are still unclear. To profile gene expression during acute and chronic neuroinflammatory stages, we treated rat midbrain neuron-glia cultures with vehicle or 10 ng/ml LPS and examined mRNA expression of some major inflammatory factors using RT-PCR at different time points (3 hours, 2, 4, 7 and 10 days after LPS/vehicle treatment). The time course studies showed a relatively delayed and persistent upregulation of mRNA expression of NOX2, the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase (Fig. 1A). This pattern was different from the rapid, dramatic and transient upregulation of inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6 and IL-10 as well as inflammatory enzymes iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase; NOS2) and cyclooxygenase-2 (data not shown). The rapid and transient upregulation of these inflammatory mediators support their well-known and important roles for the initiation and the resolution of acute inflammation. Sustained upregulation of NOX2 mRNA implied a possible role of NADPH oxidase on the transition from acute inflammation to a chronic one as well as the formation and the maintenance of chronic inflammation. Before testing this possibility, we first characterized expression patterns of NOX2 protein. Immunoblotting and representative images of Immunocytochemistry detected a significant increase in the level of NOX2 protein at 2 days after LPS treatment of neuron-glia cultures, and NOX2 upregulation was sustained up to 7 days, the longest time point examined in these experiments (Fig.1 B–D).

Fig. 1. LPS induced persistent upregulation of NOX2 in both microglia and neurons in neuron-glia cultures.

A-C Rat midbrain neuron-glia cultures were challenged with vehicle or LPS (10 ng/ml; the concentration used in all in vitro experiments unless otherwise indicated). The expression of mRNA and protein of NOX2 (gp91phox) was measured by using RT-PCR (A) and Western blotting (B) with densitometry analysis (C) at indicated time points. Results are mean ± SEM of three experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). *p < 0.05 compared with time-matched vehicle-treated controls. D, E Rat midbrain neuron-glia cultures were treated with vehicle or LPS for 6 days. D Representative immunohistochemical analysis showed that NOX2 was persistently upregulated during chronic neuroinflammation. E Representative images of double-labelled immunofluorescence showed increased expression of NOX2 (green) in neurons (red staining for neuronal maker Nissl) after LPS treatment. All immunoblotting and immunostaining images were representative of three independent experiments. Scale bars in (D) and (E) are 50 and 10 μm, respectively.

Multiple lines of evidence including ours have demonstrated a pivotal role of over-activated microglial NADPH oxidase in chronic oxidative stress, sustained neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration [10–12]. Recent studies have reported that NADPH oxidase is not only expressed in microglia but also expressed in neurons, astrocytes, and the neurovascular system in the central nervous system [12, 16, 32, 33]. In the present study, we investigated whether neuronal NADPH oxidase also contributed to chronic oxidative stress, sustained neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration in models of PD. We first examined expression of NOX2 on neurons in LPS-treated neuron-glia cultures (a cellular model of PD) and in the SN of a chronic mouse model of PD. Double-labeled immunofluorescence showed remarkable upregulation of NOX2 (green) in both Iba-1-IR microglia (data not shown) and Nissl-positive neurons (red) after LPS treatment of rat midbrain neuron-glia cultures for 6 days (Fig. 1E).

In vivo characterization of time-dependent upregulation of neuronal NOX2 and its functional outcomes

A time-course study was performed to determine patterns of NOX2 expression in microglia and neurons in a chronic mouse model of PD generated by an intraperitoneal injection of LPS (5 mg/kg; 15 × 106 EU/kg). Triple-labelled immunofluorescence conducted on frozen brain slices containing the SN region at 1 day (acute inflammation) and 6, 12, and 18 months (chronic inflammation) after LPS injection showed persistent upregulation of NOX2 in Iba-1-IR microglia and MAP-2-IR neurons (Fig. 2A). The quantification of fluorescence intensity showed time-dependent increases in the overall level of NOX2 in microglia and neurons in LPS-injected groups (Fig. 2B). In saline-injected group, NOX2 also showed aging-related increases. Notably, the increase of NOX2 in LPS-injected groups was much greater than that of saline-injected group. Our previous Immunoblotting results showed NOX2 upregulation in midbrains of three chronic in vivo PD models, namely mice models at 1 year after an intraperitoneal injection of 5 mg/kg LPS, 3 or 7 months after daily subcutaneous injection of MPTP (15 mg/kg/day) for 6 days and 1-year-old A53T α-synuclein transgenic mice; NOX2 upregulation was positively associated with microglial activation and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the first two models [3]. Further determination of cellular location of persistently upregulated NOX2 by quantitative measurement of NOX2 fluorescence intensity in neurons or microglia revealed different expression patterns of NOX2 on these cells. One day after LPS injection, the upregulation of NOX2 was mainly occurred in microglia (Fig. 2A, C). At later time points (6–18 months), enhanced expression of microglial NOX2 in LPS-injected mice was off the peak but still remained much higher than that of saline-injected mice and reached the peak level again at 18 months after LPS injection (Fig. 2C). Another striking change was a time-dependent dramatic increase in NOX2 in MAP-2-IR neurons in the SN during the chronic neuroinflammatory stage (i.e., 6–18 months after LPS injection) (Fig. 2A, C).

Fig. 2. The SN of a chronic mouse model of PD showed persistent upregulation of NOX2 in microglia and neurons as well as elevated oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation.

A-C Frozen brain slices (16 μm in thickness) from C57BL/6 mice with an intraperitoneal injection of saline or LPS (5 mg/kg; 15 × 106 EU/kg; the dose used for all in vivo experiments) were triple-stained for NOX2 (red), MAP-2 (green), and Iba-1 (purple) at 1 day or 6, 12 and 18 months after the injection. A The representative confocal fluorescence images of the SN region were shown. The scale bar is 50 μm. The zoomed images were shown in the upper right corner of the corresponding images, and the scale bar in the zoomed images is 10 μm. B The quantification of fluorescence intensity of overall levels of NOX2 in the SN of saline- and LPS-injected mice. C The quantification of fluorescence intensity of microglial NOX2 and neuronal NOX2 at the indicated time points after vehicle/LPS injection. *p < 0.05 versus saline-injected mice. D At 1, 8, and 18 months after LPS/saline injection, mice were injected intraperitoneally with DHE (30 mg/kg). Brains were then harvested 30 minutes later. Fluorescent images of mouse brain cryosections showed double-labeling for ethidium and 2-hydroxyethidium (red) and TH (green) after DHE oxidation. E Mice injected with saline or LPS were scarified at 1.5, 4.5, 12, and 20 months after the injection. Lipid peroxidation was evaluated by the measurement of the level of MDA. Data are mean ± SEM from 5 mice for each time point (B, C and E). *p < 0.05 versus the corresponding 1.5-month group. #p < 0.05 versus time matched saline-injected groups. All immunostaining images were representative of 5 mice for each time point (A, D).

To further determine functional outcomes of persistent NOX2 upregulation, we detected oxidation of DHE to examine iROS production and cellular oxidative stress in mouse neurons in situ. At 1, 8 and 18 months after an intraperitoneal injection of LPS or 0.9% normal saline, the mice were intraperitoneally injected with DHE. Upon oxidation in live cells, DHE is converted to 2-hydroxyethidium (the superoxide-specific product) and other fluorescent products, particularly ethidium, thereby being used to detect cellular oxidative stress. The red fluorescence of ethidium and 2-hydroxyethidium in nigral TH-IR dopamine neurons was faint in saline-injected control mice but remarkably increased in LPS-injected mice, particularly at 8 and 18 months after LPS injection, indicating persistent cellular oxidative stress in these neurons under chronic neuroinflammation (Fig. 2D). Moreover, lipid peroxidation, as shown by the level of MDA, was significantly increased in the brain of LPS-injected mice compared with age-matched saline-injected mice. The level of MDA in saline-injected mice was also significantly increased at age of 20 months, which is consistent with aging-related oxidative stress (Fig. 2E). Overall, the upregulation of neuronal NOX2 was accompanied with increased ROS production in neurons and oxidative stress during chronic neuroinflammation in LPS-injected mouse brains.

LPS-elicited microglial activation triggered upregulation and activation of NADPH oxidase in neurons

Under the normal condition, the level of NADPH oxidase in non-myeloid lineage cells including neurons and astrocytes is lower than that of myeloid lineage cells including macrophages and microglia. To avoid impact of confounding factor microglial NADPH oxidase on expression and activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase and resultant ROS production in neurons with or without inflammatory stimulation, we used a transwell culture system to separately culture highly enriched midbrain neurons (> 99% neurons, < 0.5% astroglia and < 0.1% microglia) in the well of the culture plate and enriched microglia (2 to 4 × 104 microglia/insert) in the transwell insert. When preventing physical contact between neurons and microglia, this culture system allows secreted soluble inflammatory factors from activated microglia moving across the transwell membranes thereby providing inflammatory environment for neurons. ELISA measurement of TNFα secretion from neuron-enriched cultures treated with vehicle or LPS indicated scarce microglial contamination in neuron-enriched cultures or in the neuronal layer of neuron-microglia co-cultures (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Additionally, Q-PCR assay of microglial marker CD11b and astroglial marker GFAP in neuron-enriched cultures incubated for 24 hours with the conditioned medium (CM) from vehicle- or LPS-treated microglia detected no microglia or astroglia contamination (Supplemental Fig. S1B, C).

We examined expression patterns of NOX isoforms and subunits of NADPH oxidase in neurons in the transwell co-culture system with or without inflammatory stimulation, as indicated in Fig. 3A. The mRNA expression of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4 (the foremost NOX isoforms in the brain) in neurons was first determined by RT-PCR at 24 hours after LPS or vehicle treatment of the co-culture. Neurons displayed basal expression of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4 in vehicle-treated co-cultures. LPS treatment of neuron-enriched cultures did not affect the expression of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4, which indicated extremely low contamination of microglia or astroglia in the neuron-enriched cultures (Fig. 3B). LPS stimulation of microglia grown in the transwell insert specifically increased NOX2 mRNA transcript in co-cultured neurons without affecting NOX1 or NOX4. Additionally, upregulation of NOX2 mRNA in neurons elicited by soluble factors from activated microglia after LPS treatment was positively correlated with the number of microglia (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the mRNA of two main cytosolic subunits of NADPH oxidase (p47phox and p67phox) was also elevated in neurons after LPS treatment of the co-cultured microglia (Fig. 3C), indicating subunits of neuronal NADPH oxidase were also up-regulated during neuroinflammation. Western blot showed increased expression of NOX2 (gp91phox) and p67phox proteins in neurons after LPS treatment of the co-cultured microglia (Fig. 3D, E).

Fig. 3. Upregulation and activation of NDAPH oxidase in neurons under inflammatory conditions.

A-G. Rat neurons and microglia were separately cultured in a transwell system. This was achieved by seeding different amount of enriched microglia on the porous membrane of transwell inserts that were placed above neuronal layer grown in the well of the plate. At 24 hours after LPS or vehicle treatment of the co-cultures, neurons were collected for the measurement of mRNA or protein of subunits of NADPH oxidase. A Schematic diagram of the transwell cell culture system. B The mRNA expression of the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase, NOX1, NOX2 (gp91phox) and NOX4 isoforms in neurons was determined by using RT-PCR. C RT-PCR detected mRNA expression of cytosolic subunits (p47phox and p67phox) in neurons. D The protein level of NOX2 and p67phox in neurons was determined by Western blot. E The ratios of the densitometry values of NOX2 or p67phox relative to GAPDH in (C) were normalized to vehicle-treated control. F Membrane and cytosolic fractions were isolated from neurons and used for examination of membrane translocation of cytosolic subunit p47phox by Western blot. ATP1B3 and β-actin were used to monitor loading errors of membrane and cytosolic proteins respectively. G The densitometry values of p47phox relative to ATP1B3 or β-actin in (F) were normalized to vehicle-treated control. H The mRNA expression of major subunits of NADPH oxidase (NOX2, p47phox and p67phox) in N27 neuronal cell line was examined by RT-PCR after N27-microglia co-cultures grown in the transwell system were treated with LPS/vehicle for 24 hours. Data are shown as means ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (B, C, E, G and H; n = 3). *p < 0.05 compared with the corresponding saline-treated controls.

It is well-established that the membrane translocation of cytosolic subunit p47phox is required for microglial NADPH oxidase activation and is generally used as a marker of NADPH oxidase activation. We next investigated whether the upregulated neuronal NADPH oxidase was also functionally activated and produced superoxide radical in neurons. Neurons from vehicle- or LPS-treated co-cultures in a transwell system were homogenized and separated into cell membrane and cytosolic fractions. No membrane translocation of p47phox in neurons in vehicle-treated co-cultures or neuron-enriched cultures indicated that neuronal NADPH oxidase, like microglial NADPH oxidase, was latent under normal circumstances. By contrast, neurons in LPS-treated co-cultures displayed membrane translocation of p47phox and a decrease of p47phox in the cytosol, indicating activity-dependent enzyme complex assembly and activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase under inflammatory conditions (Fig. 3F, G). It is noteworthy that microglia/astroglia contamination in primary neuron-enriched cultures could be a confounding factor in studying neuronal NADPH oxidase in this culture system. Therefore, we modified and optimized our previous protocol for preparation of neuron-enriched cultures and significantly improved the purity of neuron-enriched cultures in the present study, as described in the Methods and shown in Supplemental Fig. S1. Importantly, in each panel of Fig. 3B–G, treatment of neuron-enriched cultures with LPS in sister wells of the culture plate was used to monitor microglia/astroglia contamination and its influence on the corresponding results in the same experimental setting. Notably, at 24 hours after LPS treatment of the co-cultures, significant upregulation of mRNA/protein of NADPH oxidase subunits and p47phox membrane translocation in neurons in the culture plate were induced only when microglia were added into the transwell insert (Fig. 3B–G). No upregulation of NADPH oxidase subunits or p47phox membrane translocation in LPS-treated neuron-enriched cultures indicated that neither negligibly contaminated microglia nor astroglia in the neuron-enriched cultures nor their inflammatory factors was responsible for the observed upregulation of NADPH oxidase subunits or p47phox membrane translocation in neurons under inflammatory conditions. To further rule out influence of negligible contamination of microglia/astroglia on expression and activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase in primary neuron-enriched cultures, we repeated some experiments using the N27 cell, an immortalized rat dopaminergic neuronal cell line. Similar results showed increased mRNA expression of NOX2, p47phox and p67phox in N27 cells in LPS-treated N27-microglia co-cultures grown in a transwell system (Fig. 3H). Collectively, under inflammatory conditions, NADPH oxidase displayed upregulation of its subunits, NOX2, p47phox and p67phox as well as activity-dependent enzyme complex assembly and activation in neurons.

Inflammatory stimulation induced neuronal NOX2-dependent iROS production in neurons

Traditionally, mitochondria are believed to be the main source of iROS in neurons. A recent study has found that NADPH oxidase, but not the mitochondrion, is the primary source of NMDA-induced rapid superoxide generation in neurons [20]. We next determined whether inflammatory stimulation induced NADPH oxidase-dependent iROS production in neurons. Since microglial NADPH oxidase is the major source of superoxide radical during neuroinflammation, to avoid impact of confounding factor microglial NADPH oxidase on ROS production in neurons in neuron-microglia co-cultures, we designed experiments to incubate neuron-enriched cultures with the CM collected from wildtype microglia-enriched cultures treated with vehicle or LPS for 24 hours (Fig. 4A). No microglia or astroglia contamination, as determined by Q-PCR assay of microglial marker CD11b and astroglial marker GFAP in neuron-enriched cultures with 24-hour incubation with the CM from vehicle- or LPS-treated microglia excluded impact of contaminated microglia/astroglia on ROS production in neurons (Supplemental Fig. S1B, C). As shown in Fig. 4B, inflammatory mediators in the CM collected from LPS-treated microglia induced iROS production in neurons, and such iROS production was prevented by pretreatment of neuron-enriched cultures with two functionally dissimilar inhibitors of NADPH oxidase, apocynin that specifically interferes with NOX2-p47phox interaction to prevent enzyme complex assembly and diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI; a widely-used nonspecific NOX2 inhibitor that reacts with multiple flavin-containing enzymes to inhibit their catalytic activities).

Fig. 4. Inflammation-induced neuronal NOX2-dependent ROS production in neurons.

A Schematic diagram of the collection of conditional medium (CM) from vehicle-/LPS-treated microglia-enriched cultures and the treatment of neuron-enriched cultures with the CM. Mouse microglia (106 cells/well) were treated with vehicle or LPS for 24 hours. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged to remove cells and/or cell debris. One milliliter of CM was added to each well containing neuron-enriched cultures. B Measurement of iROS-dependent intracellular H2DCFDA oxidation using fluorescence microplate reader to detect iROS in midbrain neuron-enriched cultures that were pretreated with apocynin (0.25 or 0.5 mM) or DPI (0.1 or 1 μM) for 30 minutes and then incubated with the CM for 24 hours. C, D Midbrain neuron-enriched cultures prepared from wildtype or NOX2−/− mice were incubated for 24 hours with the CM. Representative confocal images of a fluorescent adduct of CM-H2DCFDA after its iROS-dependent oxidation (C) and quantification of the fluorescence intensity by Image J (D). Data are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (B, D; n = 3). *p < 0.05 compared with the corresponding control cultures incubated with CM from vehicle-treated wildtype microglia. #p < 0.05 compared with the corresponding wildtype neuronal cultures incubated with CM from LPS-treated wildtype microglia (B, D). The scale bar is 20 μm.

The half-life of major ROS at physiological pH and temperature is short (milliseconds or seconds for most ROS) with the exception of H2O2 that has a relatively long half-life (minutes). Catalase and other antioxidant defence enzymes catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 [34, 35]. The blockage of inflammation-related iROS production in neurons by NADPH oxidase inhibitors (Fig. 4B) and the short half-life of ROS excluded the possibility that CM-elicited iROS production in neurons measured at 24 hours after the addition of CM was attributed to the carryover from microglia-derived extracellular ROS. Confocal images showed that the CM from LPS-stimulated microglia triggered much more iROS production in wildtype neurons than the CM from vehicle-treated microglia (Fig. 4C, D). Compared with wildtype neurons, NOX2-deficient neurons produced much less iROS after incubated with the CM from LPS-treated wildtype microglia (Fig. 4C, D). These results indicated that inflammatory mediators in the CM from LPS-treated microglia induced NOX2-dependent iROS production in neurons. Here, the incomplete prevention of iROS production by NOX2 deletion suggested that other sources such as mitochondria and/or other NOX isoforms could also partially contribute to the increased oxidative stress in neurons under inflammatory conditions. Collectively, data in Fig. 4B–D suggested that nNOX is the major source of inflammatory mediator-induced iROS production in neurons.

A positive feedback mechanism between ROS production and NOX2 upregulation underlies the sustained NOX2 upregulation

The sustained upregulation of NOX2 occurred in both microglia and neurons during the chronic neuroinflammation phase (Fig. 2A–C). We next investigated how NOX2 was persistently upregulated. The 24-hour incubation with the CM from LPS-treated microglia triggered upregulation of NOX2 mRNA in neurons, and such NOX2 upregulation was significantly reduced in the presence of ROS scavenger N-acetylcysteine (NAC, 5 mM) (Fig. 5A). Thus, it appears to form a positive feedback between increased ROS production and upregulation of neuronal NOX2 expression in neurons under inflammatory conditions. Similarly, pre-treatment with NAC for 30 min significantly attenuated LPS-elicited upregulation of NOX2 mRNA and protein in neuron-glia cultures (Fig. 5B–D). Interestingly, post-treatment with NAC at 24 hours after LPS treatment was still effective in reducing LPS-elicited upregulation of mRNA and protein of NOX2 measured at 7 days after LPS treatment (Fig. 5B–D). These findings suggested an important role of the positive feedback mechanism between excessive ROS and NOX2 upregulation in the formation and maintenance of chronic inflammation.

Fig. 5. A positive feedback mechanism underlies the sustained NOX2 upregulation.

A Rat midbrain neuron-enriched cultures were treated with vehicle or NAC (a commonly used ROS scavenger; 5 mM) and incubated for 24 hours with the CM from vehicle-/LPS-treated microglia-enriched cultures. The mRNA expression of NOX2 in neurons was determined by using RT-PCR. B-D Rat midbrain neuron-glia cultures were challenged with LPS with or without pretreatment or post-treatment with NAC (5 mM) at 30 min before or 1 day after LPS challenge. The expression of NOX2 mRNA and protein was determined using RT-PCR (B) and Immunoblotting (C, D). Pre- and post-treatment with NAC resulted in a significant reduction in the level of NOX2 mRNA and protein, indicating inflammation-associated ROS production upregulated NOX2 expression. Data are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments in triplicate (n = 3). *p < 0.05 and #p < 0.05 compared with neuron-enriched cultures incubated with CM from vehicle-treated and LPS-treated microglia respectively in (A). *p < 0.05 compared with vehicle-treated neuron-glia cultures in (B, D). #p < 0.05 compared with LPS-treated neuron-glia cultures (B, D). C: control; L: LPS; N: NAC.

Neuronal NOX2 activation enhances inflammation-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and dopaminergic neurotoxicity

Mitochondria are prone to oxidative damage. We next determined whether neuronal NOX2-derived ROS induced mitochondrial dysfunction by measuring intracellular ATP and mitochondrial membrane potential. Neuron-enriched cultures treated with the CM from LPS-stimulated microglia showed reduced intracellular ATP and mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig 6A, B), indicating mitochondrial dysfunction. Pretreatment of neuron-enriched cultures with apocynin significantly improved neuronal mitochondrial functions, as reflected by the recovery from reduction in intracellular ATP (Fig. 6A) and mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 6B). We next investigated whether neuronal NOX2 played a role in inflammation-elicited neurodegeneration. Midbrain neuron-enriched cultures were incubated with CM from vehicle- or LPS-treated microglia. Seven days later, dopaminergic toxicity was assessed by [3H]dopamine uptake and immunostaining of surviving TH-IR dopamine neurons. There was a 60% reduction in [3H]dopamine uptake in neuron-enriched cultures incubated with the CM from LPS-treated microglia (Fig. 6C). Such reduction was mitigated by pretreatment of neuron-enriched cultures with apocynin in a dose-dependent manner. Importantly, LPS-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration in neuron-microglia co-cultures was prevented by genetic deletion of neuronal NOX2. Thus, deficiency in neuronal NOX2 and resultant reduction in neuronal NOX2-dependent iROS production made neurons more resistant to LPS-induced inflammatory and oxidative neurotoxicity in neuron-microglia co-cultures (Fig. 6D, E). These results together unveiled an important role of neuronal NOX2 in inflammation-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration.

Fig. 6. Neuronal NOX2 activation triggered by inflammatory factors induced neuronal mitochondrial dysfunction and dopaminergic neurotoxicity.

A, B Intracellular ATP (A) and mitochondrial membrane potential (B) were measured in midbrain neuron-enriched cultures that were pretreated with apocynin (0.5 mM) for 30 minutes and then incubated with CM from vehicle- or LPS-treated microglia. C Midbrain neuron-enriched cultures were pretreated with apocynin (0.25 or 0.5 mM) for 30 minutes and then incubated with the CM from vehicle- or LPS-treated microglia. [3H]dopamine uptake assay was preformed to detect dopaminergic neurodegeneration 7 days after the addition of CM. D, E Midbrain neuron-enriched cultures prepared from wildtype or NOX2−/− mice with or without co-culture with wildtype microglia and vehicle/LPS treatment. Neurodegeneration was then determined by [3H]dopamine uptake assay (D) and visualized after immunostaining for TH (E) at 7 days after the treatment. Data are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (A-D; n = 3). *p < 0.05 and #p < 0.05 compared with the corresponding neuronal cultures incubated with CM from vehicle-treated and LPS-treated wildtype microglia respectively (A-C). *p < 0.05 compared with the wildtype neurons co-cultured with wildtype microglia and treated with vehicle (D). #p < 0.05 compared with the wildtype neurons co-cultured with wildtype microglia and treated with the same concentration of LPS (D). The images presented in (E) are representative of three independent experiments. The scale bar is 5 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated important contribution of neuronal NOX2 to chronic inflammatory neurodegeneration. Time-course studies revealed that LPS-induced expression patterns of NOX2 were different in microglia and neurons. Upregulation of neuronal NOX2 occurred later than that of microglial NOX2 in respond to inflammatory stimulation, but both neuronal and microglial NOX2 upregulated during chronic neuroinflammation. These expression patterns of NOX2 not only support the well-established critical pathologic role of microglial NOX2 in degenerative diseases but also suggest neuronal NOX2 might be also important for chronic neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Mechanistic studies suggested that persistent upregulation of NOX2 under neuroinflammatory conditions was regulated by a positive feedback mechanism between excessive ROS production and NOX2 upregulation. Such a positive feedback worsens the severity of neuroinflammation, sustains chronic neuroinflammation and drives neuronal death

It is well-established that a quick release of NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide radical by phagocytes is vital for host-defense in acute inflammation to combat invading microorganisms [12, 36]. However, much less is known about the significance and the mechanism of the enhanced, sustained expression of NADPH oxidase during chronic inflammatory phase. Gene profiling studies revealed that in comparison with the rapid and short-lived upregulation of genes of common inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS and cyclooxygenase-2) [37–40], upregulation of the NOX2 gene was relatively delayed and sustained in LPS-treated neuron-glia cultures (Fig. 1A). In the SN of a chronic mouse model of PD with an intraperitoneal injection of LPS, a time-dependent upregulation of NOX2 was observed from day 1 (acute neuroinflammatory stage) to 6, 12 and 18 months (chronic neuroinflammatory stage) after LPS injection. Notably, NOX2 upregulation in microglia and neurons revealed a time-dependent disparity. While almost all the NOX2-IR cells were microglia but not neurons 1 day after LPS injection, NOX2 immunostaining in MAP-2-IR neurons was remarkably upregulated at 6 months after LPS injection. The upregulation of NOX2 in neurons and microglia progressed during 6–18 months after LPS injection (Fig. 2A, C). The NOX2 expression pattern is consistent with the dual role of NADPH oxidase in neuroinflammation: 1) rapid activation and release of a large amount of superoxide radical in activated microglia are necessary for host-defense in the brain during acute neuroinflammation; 2) sustained upregulation of NOX2 expression played a pathophysiological role in chronic neuroinflammation-related neurodegeneration [10–12].

Compared with widely-studied phagocyte NADPH oxidase in various phagocytes including microglia, little is known about expression patterns and functional outcomes of neuronal NADPH oxidase. Characterization of expression of different NOX isoforms showed basal expression of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4 in neurons, but NOX2 was the only one that was upregulated under inflammatory conditions (Fig. 3B). It is likely that the constitutive expression of NOX1 and NOX4 may produce a small amount of superoxide, H2O2 and downstream ROS that can serve as a second messenger to regulate redox-related gene expression. Mechanistic studies revealed that the activation process of neuronal NOX2 resembled that of microglial NOX2 showing the cell membrane translocation of cytosolic p47phox subunit to form a functional enzyme complex and that the activation of neuronal NOX2 was also inhibited by the same NADPH oxidase inhibitors (Fig. 3 & 4). Attenuation of neuronal oxidative stress and dopaminergic neurodegeneration by genetic deletion of neuronal NOX2 (Fig. 4 & 5) indicated that increased activation and expression of neuronal NOX2 during chronic neuroinflammation induced oxidative damages to neurons. Thus, neuronal NOX2 but not NOX1 or NOX4 is the major catalytic subunit of neuronal NADPH oxidase to participate in the neuroinflammatory processes and related oxidative stress.

Although we did not measure the enzyme activity of specific NOX isoforms (NOX1, NOX2 or NOX4) through accessing inhibitory effects of their specific inhibitors/blockers or siRNA-mediated knockdown, we were able to demonstrate an important pathogenic role of neuronal NOX2 and its direct product superoxide in mediating inflammatory neurodegeneration using NOX2-deficient neurons. Specifically, after neurons were incubated with the CM from LPS-treated wildtype microglia, much less iROS production in NOX2-deficient neurons than wildtype neurons (Fig. 4C, D) indicated NOX2-dependent iROS production and oxidative stress in neurons under inflammatory conditions. Prevention of LPS-induced neurodegeneration in neuron-microglia co-cultures by specific deletion of neuronal NOX2 (Fig. 6D, E) indicated neuronal NOX2-dependent production of superoxide and its downstream iROS made neurons more sensitive to inflammatory neurotoxicity. Collectively, neuronal NOX2 activation was critical for inflammatory neurodegeneration. Interestingly, the incomplete prevention of iROS production by neuronal NOX2 deletion (Fig. 4C, D) suggested that other sources such as mitochondria and/or other NOX isoforms could also partially contribute to the increased oxidative stress in neurons under inflammatory conditions. Neurons displayed basal expression of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4. LPS stimulation of separately co-cultured microglia specifically upregulated NOX2 in neurons without affecting neuronal NOX1 or NOX4 (Fig. 3B). Whether the activity of NOX1 and NOX4 is increased in neurons under inflammatory conditions and whether NOX1 and NOX4 activity contributes to inflammatory neurodegeneration warrants further investigation in the future through utilization of specific inhibitor(s)/blocker(s), knockout or siRNA-mediated knockdown of NOX1 or NOX4 in neurons.

Previous report showed that addition of H2O2 to human neutrophil cultures quickly increased the activity of NOX2 through a Ca2+/c-Abl signaling pathway [41]. The enhanced expression of NOX2 mediated by NF-kB or PKA pathways has been documented [42, 43]. The finding that LPS-elicited increases in mRNA and protein levels of NOX2 were blocked by pre- or post-treatment with ROS scavenger NAC indicated that ROS participates in the upregulation of NOX2 expression in microglia and neurons (Fig. 5), indicating a positive feedback interaction between increased ROS production and NOX2 upregulation (Fig. 7). The positive feedback in upregulation of NOX2 is an unusual finding since expression of most enzymes are negatively regulated by increased concentrations of its products. The selective upregulation of NOX2 expression by excessive iROS is unique, since most of other proinflammatory genes, including iNOS enzyme, were not significantly altered (preliminary observations). This positive feedback cycle provides insights into a possible mechanism explaining why the affected brain regions such as the SN in PD displayed such a conspicuous time-dependent upregulation in NOX2. Together, findings from this study suggested a vital role of the positive feedback between excessive ROS production and NOX2 upregulation in the formation and maintenance of chronic inflammation.

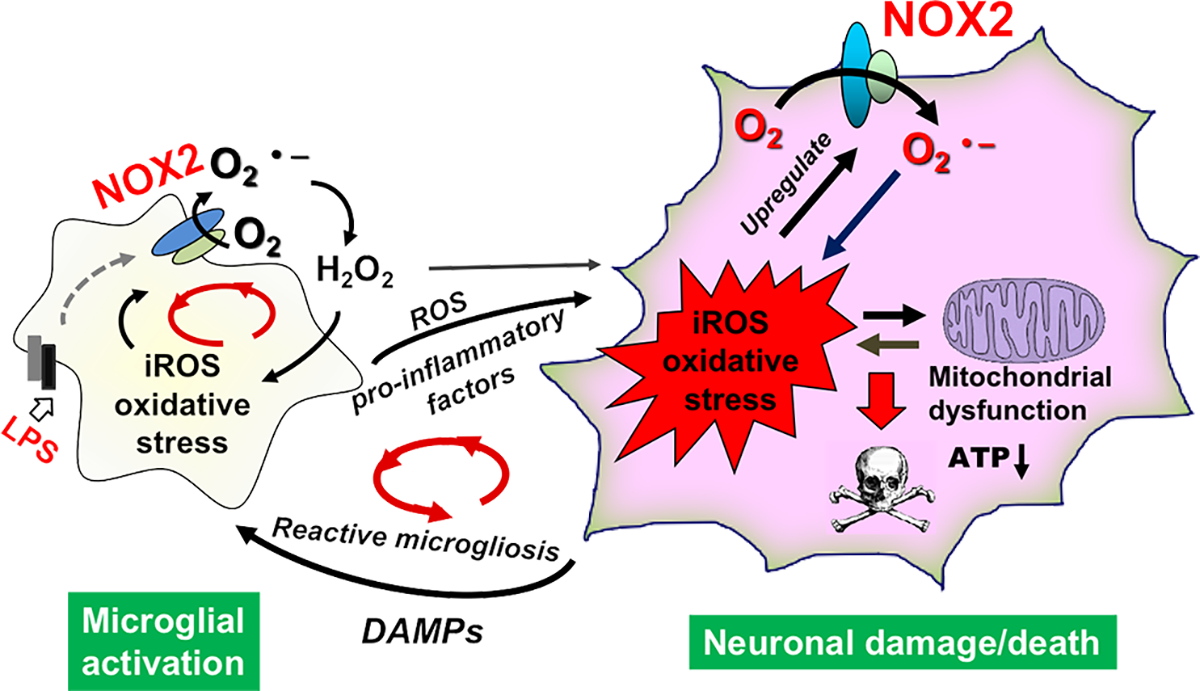

Fig. 7. Multiple positive feed-back cycles sustained chronic neuroinflammation and drove progressive neurodegeneration.

Initially, LPS triggered the activation of microglial NADPH oxidase and generated a large amount of superoxide radical, which was converted to H2O2 through superoxide dismutase. Cell membrane permeable H2O2 then entered nearby neurons to increase neuronal iROS; meanwhile pro-inflammatory factors released from activated microglia acted on neurons. As a result, expression of NOX2 was upregulated in neurons, and more neuronal NOX2-dependent iROS were produced in neurons. These results indicated the formation of a positive feedback between ROS production and neuronal NOX2 upregulation. Excessive iROS caused mitochondrial damages and dysfunction leading to leak of superoxide. Therefore, a “ROS-producing-ROS” vicious cycle was formed within neurons inducing persistent oxidative damages. As neuroinflammation and oxidative stress continued, the vicious positive feedback loop within neurons caused neuronal damages/death and leak of danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) to further trigger the reactive microgliosis and to form another positive feedback cycle between dysregulated microglial activation and neuronal damages. There were similar positive feedback cycles between ROS production and NOX2 upregulation/activation or between NOX2-derived ROS and mitochondria-derived ROS in microglia. O2.−: superoxide radical; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide.

Based on findings from this study and previous reports (37–39), we propose a model depicting the critical roles of microglial and neuronal NOX2 in sustaining chronic neuroinflammation and driving progressive neurodegeneration. Activation of microglial NOX2 increases the production of extracellular superoxide, which was converted to H2O2 through superoxide dismutase. Cell membrane permeable H2O2 then entered nearby neurons to increase neuronal iROS and oxidative stress, which in turn further activates neuronal NOX2 likely through ROS-sensitive signaling pathways, such as Ap-1 or NF-kB [44–46] and upregulates neuronal NOX2 expression. Meanwhile pro-inflammatory factors released from activated microglia acted on neurons worsen oxidative stress in neurons. As neuroinflammation and oxidative stress continue, excessive iROS and ROS-related oxidative stress causes mitochondrial damages and leak of superoxide forming a “ROS-producing-ROS” vicious cycle within neurons. Progressively, the vicious positive feedback loop within neurons causes neuron damages/death and leak of danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which further triggers reactive microgliosis and maintains another positive feedback cycle between dysregulated microglia and damaged neurons.

Conclusions

This study provides the first insights into the molecular mechanism underlying the persistent expression of neuronal NOX2 during chronic neuroinflammation. Strong evidence further implicates that enhanced NOX2 expression and increased ROS production play a critical role in the pathogenesis of inflammation-related neurodegeneration. From a translation viewpoint, this study gives strong credence to the idea of developing NOX2-targeting therapeutic agent for neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. The purity of neuron-enriched cultures is high. A Neuron-enriched and neuron-glia cultures were treated with vehicle or LPS. The supernatant was collected at 6 hours after LPS treatment and used for ELISA measurement of TNFα secretion. B, C Neuron-enriched cultures were incubated for 24 hours with conditional medium (CM) from vehicle- or LPS-treated microglia. Neuron-glia cultures were treated with LPS for 24 hours. Q-PCR assay was performed to detect expression of microglial marker CD11b (B) and astroglial marker GFAP (C). Note: neuron-glia cultures were used as positive controls in these experiments (A-C). LPS treatment was used to detect negligible contamination of microglia and astroglia in neuron-enriched cultures.

Highlights.

Progressive, persistent neuronal NOX2 upregulation during chronic neuroinflammation

Positive feedback mechanism between excessive ROS production and NOX2 upregulation

Persistent neuronal NOX2 upregulation & activation sustain chronic neuroinflammation

Persistent neuronal NOX2 upregulation and activation promote neurodegeneration

Acknowledgments:

We thank Anthony Lockhart, J. Tucker, Eli Ney and Belinda Wilson for mouse colony maintenance, assistance in confocal imaging collection, immunohistochemistry images collection, and laboratory technical support, respectively.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 31471006], the national high technology research and development program of China [grant number 2014AA021601], the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant number 021414380524], Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, and the award to high-level innovative and entrepreneurial talents of Jiangsu Province of China [grant number 0903/133032] to Hui-Ming Gao, the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 21577004] to Hui-Ming Gao and Hui Zhou. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH/NIEHS [grant number ES090082-22] to Jau-Shyong Hong.

Abbreviations

- Ara-C

Cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CD11b

Complement Component 3 Receptor 3 Subunit

- CM-H2DCFDA

Chloromethyl-29, 79-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- DAMPs

Danger-associated molecular patterns

- DHE

Dihydroethidium

- DPI

Diphenyleneiodonium chloride

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- Iba1

Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule-1

- IL-1β

Interleukin 1 beta

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- IL-10

Interleukin 10

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase; also known as NOS2

- iROS

intracellular reactive oxygen species

- KRB

Krebs–Ringer buffer

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MAP-2

Microtubule Associated Protein 2

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- MEM

Minimum essential medium

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- Neu-N

Neuron-specific nuclear protein

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- NOX2

the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SN

Substantia nigra

- TH

Tyrosine hydroxylase

- TNF-α

Tumor Necrosis Factor-α

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Declarations of interest: none

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Reference:

- [1].Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS, Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms, Nat Rev Neurosci 8(1) (2007) 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Simpson DS, Oliver PL, ROS generation in microglia: understanding oxidative stress and inflammation in neurodegenerative disease, Antioxidants 9(8) (2020) 743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tu D, Gao Y, Yang R, Guan T, Hong JS, Gao HM, The pentose phosphate pathway regulates chronic neuroinflammation and dopaminergic neurodegeneration, J Neuroinflammation 16(1) (2019) 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Geng L, Fan LM, Liu F, Smith C, Li JM, Nox2 dependent redox-regulation of microglial response to amyloid-β stimulation and microgliosis in aging, Sci Rep 10(1) (2020) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Moehle MS, West AB, M1 and M2 immune activation in Parkinson’s Disease: Foe and ally?, Neuroscience 302 (2015) 59–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jayaraj RL, Azimullah S, Beiram R, Jalal FY, Rosenberg GA, Neuroinflammation: friend and foe for ischemic stroke, J Neuroinflammation 16(1) (2019) 1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Block ML, Hong JS, Chronic microglial activation and progressive dopaminergic neurotoxicity, Biochem Soc Trans 35(Pt 5) (2007) 1127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liu Z, Zhou T, Ziegler AC, Dimitrion P, Zuo L, Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications, Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017 (2017) 2525967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kim GH, Kim JE, Rhie SJ, Yoon S, The role of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases, Exp Neurobiol 24(4) (2015) 325–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gao HM, Zhou H, Hong JS, NADPH oxidases: novel therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative diseases, Trends Pharmacol Sci 33(6) (2012) 295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chen SH, Oyarzabal EA, Hong JS, Critical role of the Mac1/NOX2 pathway in mediating reactive microgliosis-generated chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration, Curr Opin Pharmacol 26 (2016) 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bedard K, Krause KH, The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology, Physiol Rev 87(1) (2007) 245–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gao HM, Liu B, Zhang W, Hong JS, Critical role of microglial NADPH oxidase-derived free radicals in the in vitro MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease, FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 17(13) (2003) 1954–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gao HM, Zhou H, Zhang F, Wilson BC, Kam W, Hong JS, HMGB1 acts on microglia Mac1 to mediate chronic neuroinflammation that drives progressive neurodegeneration, J Neurosci 31(3) (2011) 1081–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhou H, Zhang F, Chen SH, Zhang D, Wilson B, Hong JS, Gao HM, Rotenone activates phagocyte NADPH oxidase by binding to its membrane subunit gp91phox, Free Radic Biol Med 52(2) (2012) 303–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Belarbi K, Cuvelier E, Destee A, Gressier B, Chartier-Harlin MC, NADPH oxidases in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review, Mol Neurodegener 12(1) (2017) 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ma MW, Wang J, Zhang Q, Wang R, Dhandapani KM, Vadlamudi RK, Brann DW, NADPH oxidase in brain injury and neurodegenerative disorders, Mol Neurodegener 12(1) (2017) 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wu DC, Teismann P, Tieu K, Vila M, Jackson-Lewis V, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S, NADPH oxidase mediates oxidative stress in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of Parkinson’s disease, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100(10) (2003) 6145–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ferreira SA, Romero-Ramos M, Microglia response during Parkinson’s disease: alpha-synuclein intervention, Front Cell Neurosci 12 (2018) 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brennan AM, Suh SW, Won SJ, Narasimhan P, Kauppinen TM, Lee H, Edling Y, Chan PH, Swanson RA, NADPH oxidase is the primary source of superoxide induced by NMDA receptor activation, Nat Neurosci 12(7) (2009) 857–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schiavone S, Jaquet V, Sorce S, Dubois-Dauphin M, Hultqvist M, Backdahl L, Holmdahl R, Colaianna M, Cuomo V, Trabace L, Krause KH, NADPH oxidase elevations in pyramidal neurons drive psychosocial stress-induced neuropathology, Transl Psychiatry 2 (2012) e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Xu J, Wu S, Wang J, Wang J, Yan Y, Zhu M, Zhang D, Jiang C, Liu T, Oxidative stress induced by NOX2 contributes to neuropathic pain via plasma membrane translocation of PKCε in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons, J Neuroinflammation 18(1) (2021) 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].De Virgiliis F, Hutson TH, Palmisano I, Amachree S, Miao J, Zhou L, Todorova R, Thompson R, Danzi MC, Lemmon VP, Enriched conditioning expands the regenerative ability of sensory neurons after spinal cord injury via neuronal intrinsic redox signaling, Nat Commun 11(1) (2020) 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chen SH, Oyarzabal EA, Hong JS, Preparation of rodent primary cultures for neuron-glia, mixed glia, enriched microglia, and reconstituted cultures with microglia, Methods Mol Biol 1041 (2013) 231–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu B, Wang K, Gao HM, Mandavilli B, Wang JY, Hong JS, Molecular consequences of activated microglia in the brain: overactivation induces apoptosis, J Neurochem 77(1) (2001) 182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gao HM, Jiang J, Wilson B, Zhang W, Hong JS, Liu B, Microglial activation-mediated delayed and progressive degeneration of rat nigral dopaminergic neurons: relevance to Parkinson’s disease, J Neurochem 81(6) (2002) 1285–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhou H, Liao J, Aloor J, Nie H, Wilson BC, Fessler MB, Gao HM, Hong JS, CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1) is a novel surface receptor for extracellular double-stranded RNA to mediate cellular inflammatory responses, J Immunol 190(1) (2013) 115–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Los M, Mozoluk M, Ferrari D, Stepczynska A, Stroh C, Renz A, Herceg Z, Wang ZQ, Schulze-Osthoff K, Activation and caspase-mediated inhibition of PARP: a molecular switch between fibroblast necrosis and apoptosis in death receptor signaling, Mol Biol Cell 13(3) (2002) 978–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Reers M, Smiley ST, Mottola-Hartshorn C, Chen A, Lin M, Chen LB, Mitochondrial membrane potential monitored by JC-1 dye, Meth Enzymol 260 (1995) 406–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Buettner GR, Moving free radical and redox biology ahead in the next decade (s), Free Radic Biol Med 78 (2015) 236–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Genet S, Kale RK, Baquer NZ, Alterations in antioxidant enzymes and oxidative damage in experimental diabetic rat tissues: effect of vanadate and fenugreek (Trigonella foenum graecum), Mol Cell Biochem 236 (2002) 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nayernia Z, Jaquet V, Krause KH, New insights on NOX enzymes in the central nervous system, Antioxid Redox Signal 20(17) (2014) 2815–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cooney SJ, Bermudez-Sabogal SL, Byrnes KR, Cellular and temporal expression of NADPH oxidase (NOX) isotypes after brain injury, J Neuroinflamation 10 (2013) 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sies H, Jones DP, Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21(7) (2020) 363–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].De Lazzari F, Bubacco L, Whitworth AJ, Bisaglia M, Superoxide radical dismutation as new therapeutic strategy in Parkinson’s disease, Aging Dis 9(4) (2018) 716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Panday A, Sahoo MK, Osorio D, Batra S, NADPH oxidases: an overview from structure to innate immunity-associated pathologies, Cell Mol Immunol 12(1) (2015) 5–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lund S, Christensen KV, Hedtjärn M, Mortensen AL, Hagberg H, Falsig J, Hasseldam H, Schrattenholz A, Pörzgen P, Leist M, The dynamics of the LPS triggered inflammatory response of murine microglia under different culture and in vivo conditions, J Neuroimmunology 180(1–2) (2006) 71–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Saiki P, Nakajima Y, Van Griensven LJ, Miyazaki K, Real-time monitoring of IL-6 and IL-10 reporter expression for anti-inflammation activity in live RAW 264.7 cells, Biochemical Biophys Res Commun 505(3) (2018) 885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Erickson MA, Banks WA, Cytokine and chemokine responses in serum and brain after single and repeated injections of lipopolysaccharide: multiplex quantification with path analysis, Brain Behav Immun 25(8) (2011) 1637–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Choi IS, Shin NR, Shin SJ, Lee DY, Cho YW, Yoo HS, Time course study of cytokine mRNA expression in LPS-stimulated porcine alveolar macrophages, J Vet Sci 3(2) (2002) 97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].El Jamali A, Valente AJ, Clark RA, Regulation of phagocyte NADPH oxidase by hydrogen peroxide through a Ca(2+)/c-Abl signaling pathway, Free Radic Biol Med 48(6) (2010) 798–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Anrather J, Racchumi G, Iadecola C, NF-kappaB regulates phagocytic NADPH oxidase by inducing the expression of gp91phox, J Biol Chem 281(9) (2006) 5657–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Savchenko VL, Regulation of NADPH oxidase gene expression with PKA and cytokine IL-4 in neurons and microglia, Neurotox Res 23(3) (2013) 201–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fan H, Li D, Guan X, Yang Y, Yan J, Shi J, Ma R, Shu Q, MsrA suppresses inflammatory activation of microglia and oxidative stress to prevent demyelination via inhibition of the NOX2-MAPKs/NF-κB signaling pathway, Drug Des Devel Ther 14 (2020) 1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Khanal T, Kim HG, Do MT, Choi JH, Chung YC, Kim HS, Park Y-J, Jeong TC, Jeong HG, Genipin induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression via NADPH oxidase, MAPKs, AP-1, and NF-κB in RAW 264.7 cells, Food Chem Toxicol 64 (2014) 126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wang J, Ma MW, Dhandapani KM, Brann DW, Regulatory role of NADPH oxidase 2 in the polarization dynamics and neurotoxicity of microglia/macrophages after traumatic brain injury, Free Radic Biol Med 113 (2017) 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. The purity of neuron-enriched cultures is high. A Neuron-enriched and neuron-glia cultures were treated with vehicle or LPS. The supernatant was collected at 6 hours after LPS treatment and used for ELISA measurement of TNFα secretion. B, C Neuron-enriched cultures were incubated for 24 hours with conditional medium (CM) from vehicle- or LPS-treated microglia. Neuron-glia cultures were treated with LPS for 24 hours. Q-PCR assay was performed to detect expression of microglial marker CD11b (B) and astroglial marker GFAP (C). Note: neuron-glia cultures were used as positive controls in these experiments (A-C). LPS treatment was used to detect negligible contamination of microglia and astroglia in neuron-enriched cultures.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.