Abstract

T-cell-deficient nude mice infected with Leishmania donovani were treated with miltefosine and then given either no treatment or intermittent miltefosine. Intracellular visceral infection recurred in untreated mice but was suppressed by once- or twice-weekly oral administration of miltefosine. Miltefosine may be useful as oral maintenance therapy for T-cell-deficient patients with visceral leishmaniasis.

In an experimental model of visceral leishmaniasis caused by the intracellular protozoan Leishmania donovani, the activities of a new oral antileishmanial agent, hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine) (6, 17, 18), in T-cell-deficient athymic (nude) and T-cell-intact euthymic mice proved comparable (12). This result raised the possibility that miltefosine may have a role as an initial oral treatment approach to the growing problem of AIDS-associated visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) in CD4 cell-depleted patients (1, 4, 11).

A second, related therapeutic issue in this clinical setting is relapse of infection once any initially effective treatment is discontinued (1, 2, 7, 8, 11, 13, 15; R. N. Davidson and R. Russo, Letter, Clin. Infect. Dis. 91:560, 1994). Since successful host defense against this disease, including the prevention of posttreatment relapse, is T-cell dependent and driven by CD4 (Th1) cell-derived cytokines (9, 11, 13, 14), it is not surprising that recurrence of AIDS-related kala-azar is predictable if therapy is stopped (1, 2, 7, 8, 11, 13, 15; Davidson and Russo, Letter, Clin. Infect. Dis., 1994). This study extended the analysis of miltefosine by testing whether it may also be useful as a long-term treatment to prevent recrudescence of visceral infection in the T-cell-deficient host.

Materials and Methods. (i) Animals and visceral infection.

Athymic (nude) BALB/c mice (20 to 30 g) (Charles Rivers Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) were injected via the tail vein with 1.5 × 107 hamster spleen-derived L. donovani amastigotes (one Sudan strain) (12). Visceral infection was monitored microscopically using Giemsa-stained liver imprints, and liver parasite burdens were measured by calculating, in a blinded fashion, the number of amastigotes per 500 cell nuclei multiplied by the liver weight (in milligrams) (Leishman-Donovan units [LDU]) (12). The histologic reaction in the liver was assessed using formalin-fixed, stained tissue sections (12).

(ii) Initial and maintenance treatment.

Two weeks after L. donovani challenge, liver parasite burdens were determined for 4 of 28 infected mice, and then the animals received either no treatment (n = 4) or oral miltefosine by gavage (n = 20). Miltefosine, generously provided as a powder by ASTA Medica AG (Frankfurt, Germany), was dissolved in tap water and administered once daily at 25 mg/kg of body weight in a volume of 0.3 ml for five consecutive days (12). Two days after treatment ended, four untreated and four treated mice were sacrificed. LDU at this point (week 3) were compared to initial LDU (at week 2) to determine the extent of initial parasite killing (12). The remaining 16 treated mice were randomly divided into four groups to receive, for the next 9 weeks, either no further treatment or single doses of miltefosine (25 mg/kg) given twice weekly, once weekly, or every 2 weeks. Twelve weeks after infection, liver parasite burdens were determined for all animals.

Results and discussion.

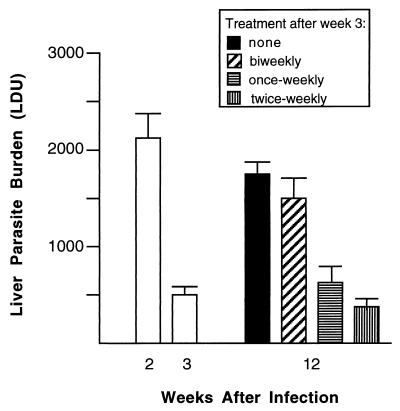

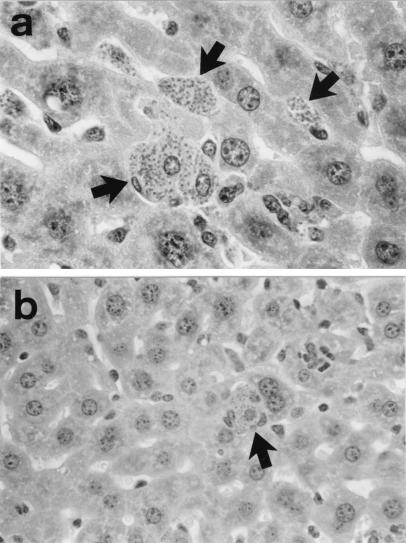

Between week 2 and week 3, the period during which miltefosine was initially administered, liver parasite burdens increased in untreated nude mice from 2,124 ± 269 (Fig. 1) to 2,994 ± 212 LDU (mean ± the standard error of the mean [SEM]) (n = 8, data not shown). In mice treated for 5 days, LDU (mean ± SEM) at week 3 were reduced to 496 ± 87, indicating 77% initial killing 1 week after therapy began (Fig. 1). Treated mice were then given either no additional miltefosine or single doses twice per week, once per week, or every second week for the next 9 weeks. As shown in Fig. 1, parasite replication resumed in treated mice that were given no additional drug, and liver burdens at week 12 were 3.5-fold higher than those at week 3. While miltefosine administered biweekly did not prevent recurrence of visceral replication, treatment given once or twice weekly was clearly active in suppressing infection for the duration of the experiment. Histologic examination of the livers at week 12 confirmed these effects (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Initial effect of miltefosine treatment in nude BALB/c mice and prevention of subsequent relapse. Two weeks after infection, nude mice were initially treated with drug for 5 days. Two days later (end of week 3), treated mice either were given no further drug or received single doses every second week, once weekly, or twice weekly for the next 9 weeks. Results are from two experiments and are means ± SEMs for seven to eight mice per group.

FIG. 2.

Photomicrographs of livers of nude mice 12 weeks after L. donovani infection. (a) Mice treated with miltefosine during week 2 to 3 only (no maintenance therapy) show recurrent infection, with multiple heavily parasitized foci (arrows). Magnification, ×500. (b) In contrast, mice treated during week 2 to 3 and twice weekly thereafter show markedly reduced liver parasite burdens at week 12, with only one infected focus in a lower-power field (arrow). Magnification, ×315.

Intracellular Leishmania organisms are probably seldom, if ever, entirely eradicated even from healthy hosts by either antileishmanial chemotherapy or the T-cell-dependent, cytokine-driven mechanism which develops to regulate successful acquired resistance and prevention of relapse in visceral infection (3, 9, 10, 13, 14, 16). In T-cell-depleted or -deficient hosts with kala-azar, such as individuals with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease (1) or immunosuppressed transplant recipients (5), not only may an initial response to treatment be difficult to induce, but also relapse after such an apparent response is frequent once therapy is discontinued (1, 2, 5, 7, 8, 11, 13, 15; Davidson and Russo, Letter, Clin. Infect. Dis., 1994). Although not yet well studied, current evidence regarding AIDS-related kala-azar suggests that maintenance treatment with once-monthly injections of pentavalent antimony may suppress recurrent infection (15); however, monthly pentamidine injections (7) or daily oral allopurinol use appears to have little effect (15).

While it still needs to be tested in patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus, miltefosine is remarkably active in kala-azar (6, 17, 18) and has additional advantages: (i) a long circulating half-life (∼8 days) (17) and (ii) experimental antileishmanial efficacy which is direct and does not require a host T-cell-dependent response for full expression (12). The results reported here suggest that miltefosine has promise as a convenient oral treatment to suppress or prevent relapse of visceral infection in the T-cell-deficient host.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant AI 16963.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvar J, Cañavate C, Gutiérrez-Solar B, Jiménez M, Laguna F, López-Vélez R, Molina R, Moreno J. Leishmania and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection: the first 10 years. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:298–319. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.2.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cascio A, Gradoni L, Scarlata F, Gramiccia M, Giordano S, Russo R, Scalone A, Camma C, Titone L. Epidemiologic surveillance of visceral leishmaniasis in Sicily, Italy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:75–78. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.deRossell R, deDuran R, Rossell O, Rodriguez A M. Is leishmaniasis ever cured? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:251–253. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90297-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desjeux P UNAIDS. Leishmania and HIV in gridlock. WHO and the UNAIDS WHO/CTD/LEISH/98.9 Add. 1 and UNAIDS/98.23. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez-Perez J, Yebra-Bango M, Jimenez-Martinez E, Sanz-Mareno C, Cuervas-Mons V, Pulpon L, Ramos-Martinez A, Fernandez-Fernandez J. Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) in solid organ transplantation: report of five cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:918–921. doi: 10.1086/520457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jha T K, Sundar S, Thakur C P, Bachmann P, Karbwang J, Fischer C, Voss A, Berman J. Efficacy and toxicity of miltefosine, an oral agent, for the treatment of Indian visceral leishmaniasis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1795–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912093412403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laguna F, Adrados M, Alvar J, Soriano V, Valencia M E, Moreno V, Polo R, Verdjo J, Jimenez M I, Martinez P, Martinez M L, Gonzalez-Lahoz J M. Visceral leishmaniasis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:898–903. doi: 10.1007/BF01700556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laguna F, Lopez-Velez R, Pulido F, Salas A, Torre-Cisneros J, Torres E, Medrano F J, Sanz J, Pico G, Gomez-Rodriquez J, Pasquan J, Alvar J. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients: a randomized trial comparing meglumine antimoniate with amphotericin B. AIDS. 1999;13:1063–1070. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199906180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray H W, Hariprashad J, Fichtl R. Models of relapse of experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1041–1043. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray H W. Granulomatous inflammation: host antimicrobial defense in the tissues in visceral leishmaniasis. In: Gallin J, Synderman R, Fearon D, Haynes B, Nathan C, editors. Inflammation: basic principles and clinical correlates. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 977–994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray H W. Kala-azar as an AIDS-related opportunistic infection. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 1999;13:459–465. doi: 10.1089/108729199318183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray H W, Delph-Etienne S. Visceral leishmanicidal activity of hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine) in mice deficient in T cells and activated macrophage microbicidal mechanisms. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:795–799. doi: 10.1086/315268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray, H. W. Treatment of kala-azar in 2000: a decade of progress and future approaches. Int. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Pearson R D, de Queiroz Sousa A. Clinical spectrum of leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:1–13. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribera E, Ocana I, Otero J, Cortes E, Gasser I, Pahissa A. Prophylaxis of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients. Am J Med. 1996;100:496–501. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)89503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Runey G L, Jarecki-Black J C, Runey M W, Glassman A B. Antithymocyte serum suppression of immunity in mice immunized to Leishmania donovani. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1990;20:263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundar S, Rosenkaimer F, Makharia M K, Goyal A K, Mandal A K, Voss A, Hilgard P, Murray H W. Trial of oral miltefosine for visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1998;352:1821–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundar S, Gupta L B, Makharia M K, Singh M K, Voss A, Rosenkaimer F, Engel J, Murray H W. Oral treatment of visceral leishmaniasis with miltefosine. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1999;93:589–597. doi: 10.1080/00034989958096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]