Abstract

Phosphomannomutase-2-congenital disorder of glycosylation (PMM2-CDG) is the most common CDG and presents with highly variable features ranging from isolated neurologic involvement to severe multiorgan dysfunction. Liver abnormalities occur in in almost all patients and frequently include hepatomegaly and elevated aminotransferases, although only a minority of patients develop progressive hepatic fibrosis and liver failure. No curative therapies are currently available for PMM2-CDG, although investigation into several novel therapies is ongoing. We report the first successful liver transplantation in a 4-year-old patient with PMM2-CDG. Over a 3-year follow-up period, she demonstrated improved growth and neurocognitive development and complete normalization of liver enzymes, coagulation parameters, and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin profile, but persistently abnormal IgG glycosylation and recurrent upper airway infections that did not require hospitalization. Liver transplant should be considered as a treatment option for PMM2-CDG patients with end-stage liver disease, however these patients may be at increased risk for recurrent bacterial infections post-transplant.

Keywords: glycosylation, CDG, phosphomannomutase, PMM2-CDG, immunoglobulin, liver transplantation, infection

1. INTRODUCTION

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are a group of rare, heterogeneous metabolic disorders caused by defects in cellular glycosylation. This group of disorders, first described in the 1980s, continues to expand rapidly, with over 170 subtypes described to date (Ferreira et al., 2018, Piedade et al., 2022).

Phosphomannomutase 2-congenital disorder of glycosylation (PMM2-CDG, OMIM: 601785), formerly known as CDG-Ia, is the most common CDG, affecting over 900 patients worldwide (Witters et al., 2018). The PMM2 gene encodes the phosphomannomutase enzyme which catalyzes the conversion of mannose-6-phosphate to mannose-1-phosphate, an essential substrate for the biosynthesis of N-linked glycoproteins (Sparks et al., 2015). Patients with PMM2-CDG present with a highly variable phenotype ranging from isolated neurologic involvement (developmental delay, strabismus, stroke-like episodes, seizures, cerebellar ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, hypotonia) to severe multi-system disease including cardiac defects, failure to thrive, liver disease, coagulopathy, frequent infections, and endocrine abnormalities (Krasnewich et al., 2007). Dysmorphic facial features, inverted nipples, and abnormal subcutaneous fat distribution are characteristically seen (Ferreira et al., 2018). Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) analysis, a common screening test for CDG, usually demonstrates a type 1 pattern (increased asialo- and disialotransferrin, decreased tetrasialotransferrin) (Lefeber et al., 2011, Witters et al., 2018). The diagnosis is confirmed either through measurement of phosphomannomutase activity or molecular analysis of the PMM2 gene (Ferreira et al., 2018).

Currently, a few CDG are known to improve with dietary therapies (Witters et al., 2017, Brasil et al., 2018). The first reported such CDG was phosphomannose isomerase-CDG (MPI-CDG), which responds to high-dose oral mannose (de Lonlay et al., 2008, Hendriksz et al., 2001, Westphal et al., 2001). Despite promising in vitro studies showing rescue of glycosylation in PMM2-deficient fibroblasts supplemented with mannose (Panneerselvam et al., 1996, Rush et al., 2000), subsequent trials of oral and intravenous mannose therapy in PMM2-CDG patients did not demonstrate clinical or biochemical improvement (Mayatepek et al., 1997, Mayatepek et al., 1998, Kjaergaard et al., 1998). To date, a disease-specific treatment remains elusive for PMM2-CDG, although investigation into novel therapies is ongoing (Brasil et al., 2018, Witters et al., 2017, Witters et al., 2018, Boyer et al., 2022).

Here, we report the first successful liver transplantation in a patient with PMM2-CDG, advocate for transplant as a treatment option for PMM2-CDG patients with complications from end-stage liver disease, and review the secretory N-glycosylation changes post-transplantation.

2. PATIENT AND METHODS

2.1. Patient presentation

Our patient was born at 39 weeks gestation after an uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery. Her birth parameters included weight 2.92 kg, length 50.8 cm, and head circumference 32.5 cm. From an early age, she was noted to have marked hypotonia, microcephaly, strabismus, decreased hearing, and abnormal fat distribution. Global developmental delay was apparent by 4 months. By 7 months of age, she developed feeding difficulties, recurrent infections, hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia, chronic diarrhea, and failure to thrive, and ultimately required percutaneous gastrojejunostomy, continuous jejunal tube feeding, and diazoxide therapy. She was referred to pediatric genetics, at which time physical examination was notable for deep-set eyes, upslanted palpebral fissures, inverted nipples, suprapubic fat pads, palpable liver edge 2 finger breadths below the costal margin, decreased strength, and hypotonia. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed mild cerebellar atrophy. Liver ultrasound showed borderline hepatomegaly and steatosis. Laboratory studies were notable for mildly elevated aminotransferases, decreased antithrombin and coagulation factors, and normal endocrine testing (Table 1). CDT analysis showed a type 1 CDG pattern (Table 2). Genetic testing revealed compound heterozygous c.338C>T (p.Pro113Leu) and c.710C>G (p.Thr234Arg) pathogenic variants in PMM2.

Table 1.

Laboratory studies in PMM2-CDG patient pre- and post-transplant.

| Pre-transplant | Post-transplant | Reference range | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | 1 month | 12 months | 36 months | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.7 | 9.4 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 11.1 | 11.4–14.3 |

| Platelets (x109/dL) | 161 | 102 | 238 | 268 | 204 | 187–445 |

| WBC (x109/dL) | 5.3 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.4–12.9 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 131 | 139 | 140 | 141 | 141 | 135–145 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 12 | 4 | 18 | 15 | 13 | 7–20 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.19–0.49 |

| ALT (U/L) | 52 | 68 | 9 | 26 | 20 | 7–45 |

| AST (U/L) | 56 | 52 | 21 | 42 | 28 | 8–50 |

| ALP (U/L) | 215 | 43 | 66 | 141 | 138 | 142–335 |

| GGT (U/L) | 152 | 30 | 30 | 55 | 21 | <21 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.5–5.0 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.5 | 0.4 | <0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ≤1.0 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | <0.2 | <0.2 | <0.2 | <0.2 | <0.2 | 0.0–0.3 |

| Ammonia (mcmol/L) | 35 | <10 | --- | 20 | 20 | ≤30 |

| Factor VII activity (%) | 50 | --- | --- | 36 | - | 65–180% |

| Factor IX activity (%) | 70 | --- | --- | --- | 70 | 65–140% |

| Factor XI activity (%) | 30 | 44 | 91 | 96 | 92 | 55–150% |

| Antithrombin | 33 | 65 | 114 | 144 | 105 | 80–130% |

| TSH (mIU/L) | 3.4 | --- | 4.7 | 5.4 | 4.1 | 0.7–6.0 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 102 | --- | --- | 145 | 131 | <170 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 664 | 36 | --- | 495 | 1110 | 386–1470 |

WBC=white blood cell count, BUN=blood urea nitrogen, ALT=alanine aminotransferase, AST=aspartate aminotransferase, ALP=alkaline phosphatase, GGT=gamma-glutamyl transferase, INR=International Normalized Ratio, TSH=thyroid-stimulating hormone, IgG= immunoglobulin G.

Table 2.

Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) analysis in PMM2 patient pre- and post-transplant.

| Structure | Pre transplant |

Post-transplant | Reference range |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 days |

14 days |

1 month |

12 months |

36 months |

||||

| Disialo/tetrasialo-transferrin |

|

1.12 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | ≤0.06 |

| Asialo/tetrasialo-transferrin |

|

0.260 | 0.076 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.005 | ≤0.011 |

| Trisialo/tetrasialo-transferrin |

|

0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | ≤0.05 |

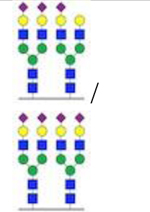

Pre-transplant, the patient had an elevated ratio of disialo- and asialotransferrin to tetrasialotransferrin and a normal ratio of trisialo- to tetrasialotransferrin, consistent with a type I CDG. Two days post-transplant, the CDT pattern showed improvement, and by 14 days post-transplant had completely normalized. ( = N-acctylglucosaminc (GlcNAc),

= N-acctylglucosaminc (GlcNAc),  = mannose,

= mannose,  = galactose,

= galactose,  = sialic acid)

= sialic acid)

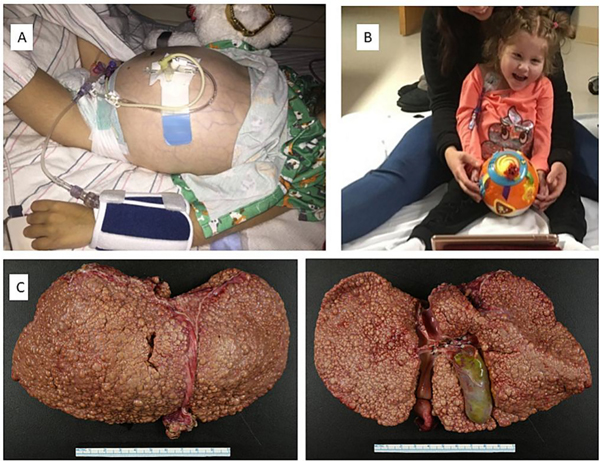

Around 3 years of age, she developed intermittent vomiting, chronic abdominal pain, and recurrent ascites requiring diuretic therapy and repeated paracenteses (Figure 1A). Repeat liver ultrasound showed coarsened hepatic echotexture consistent with cirrhosis. She was hospitalized several times due to complications of end-stage liver disease, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, and esophageal variceal bleeding which was treated with sclerotherapy and variceal band ligation. Her nutritional status deteriorated, and she remained severely developmentally delayed, unable to hold her head up, track or establish eye contact, or maintain upright posture without support. She was fed by a gastrojejunostomy tube with continuous elemental formula and did not take any oral feeding. She suffered from recurrent hypoglycemia. She also suffered a stroke-like episode at 4 years but recovered over a prolonged (8 month) period.

Figure 1.

Clinical photographs of the PMM2-CDG patient before (A) and 1.5 year after (B) liver transplantation. Prior to transplant, she suffered from complications of cirrhosis, including ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and was developmentally stagnant. After transplant, she progressed in her developmental milestones and acquired good head control and improved motor coordination. Figure 1C. HE staining of the liver explant. Anterior and posterior views of the explanted liver, showing diffuse macronodular cirrhosis.

2.1.1. Patient enrollment

Our PMM2-CDG patient was enrolled in the Frontiers in Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (FCDGC) natural history study and biomarker discovery study at Mayo Clinic. Retrospective and prospective data collection was part of the study according to the IRB, as the patient had been previously followed with the standard of care. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s mother. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic data were collected as part of the natural history study (IRB: 19-005187). Fibroblast cultures were collected as part of routine clinical care. Residual, de-identified material was used in this study (including protein expression, mRNA expression, PMM2 enzyme activity measurements). Urine samples were collected during the natural history study visit, in parallel with clinical data assessment under IRB: 16-004682.

2.2. Pre- and post-transplant assessment of clinical phenotype using NPCRS and ICARS scores

Disease severity at the time of the liver transplant and at 12 months, 24 months, and 36 months post-transplant was assessed using the Nijmegen Pediatric CDG Rating Scale (NPCRS), a validated, comprehensive clinical tool for evaluating disease severity in CDG (Achouitar et al., 2011, Ligezka et al., 2022). The NPCRS score is divided into multiple domains (Section I: Current Function, maximum 21; Section II: System Specific Involvement, maximum 30; Section III: Current Clinical Assessment, maximum 31; total maximum 82) and stratifies patients into mild (0–14), moderate (15–25), and severe (>25) disease categories.

To assess our patient’s cerebellar function pre- and 36 months post-transplant, she was evaluated using the International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS), a validated semiquantitative assessment of cerebellar ataxias. The ICARS score is graded on a 100-point scale (0=normal, 100=most severe) and is divided into four subscores, including I: Posture and Gait Disturbance (maximum 34), II: Kinetic Functions (maximum 52), III: Speech Disorders (maximum 8), and IV: Oculomotor Disorders (maximum 6) (Trouillas et al.,1997).

2.3. Pre and post-transplant assessment of carbohydrate deficient transferrin analysis

We analyzed transferrin glycoforms, including disialo- to tetrasialo- and asialo- to tetrasialo-transferrin ratios, by mass spectrometry (MS) in our patient pre and post-transplant. Carbohydrate deficient transferrin analysis is a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-validated test at Mayo Clinic. The measurements were performed under the FCDGC biomarker discover study (IRB: 16-004682).

2.4. Post-transplant quantitative assessment of fractionated serum N-glycoproteins

As evidence of biochemical improvement following transplant, quantitative assessment of fractionated serum N-glycoproteins was performed, as previously described (Alharbi et al., 2023). Total glycoproteins in 15 μL plasma were fractionated into three groups using affinity columns: (1) immunoglobulins (IgG), (2) transferrin, and (3) the remaining glycoproteins depleted of IgG, transferrin, and albumin using a protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), followed with an IgG plus albumin duo depletion spin column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and an anti-transferrin affinity spin column as described previously (Li et al., 2015). Purified IgG was eluted from the initial protein G column and purified transferrin was eluted from anti-transferrin affinity column. The remaining glycoprotein fraction was collected after passing plasma through a protein G column, IgG plus albumin duo depletion column, and an anti-transferrin affinity column sequentially. The purity of intact proteins in each fraction was evaluated by Ultra High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography Electrospray Ionization-Quadrupole Time of Flight (UPLC-ESI-QTOF) Mass Spectrometry analysis using a SYNAPT G2-Si ™ system (Waters Corporation, Plymouth Meeting, PA). No cross-contamination of glycoproteins in each fraction was detected. N-glycan from 50–60 μg of IgG, 15–20 μg of transferrin, and 50–60 μg of remaining glycoproteins were used for N-glycan analysis, respectively. N-glycans were released from each fraction using a rapid PNGaseF digestion, derivatized with a modified quinolone tagging to the transient glycosyl amide and purified using a 96-well Hilic plate (Waters Corporation) as described previously. A flow-injection-ESI-QTOF Mass Spectrometry method was used for the N-glycan analysis. A glycopeptide standard with isotope-labeled disialoglycan was used as the internal standard. The abundance of each glycan is reported as percentage of total glycans (Chen et al., 2019).

Our patient’s post-transplant N-glycan analysis was compared to those of non-CDG post-transplant patients and healthy controls. Unfortunately, due to limited amount of pre-transplant serum, N-glycan analysis for our patient prior to liver transplant was not performed.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Liver transplant and post-transplant course

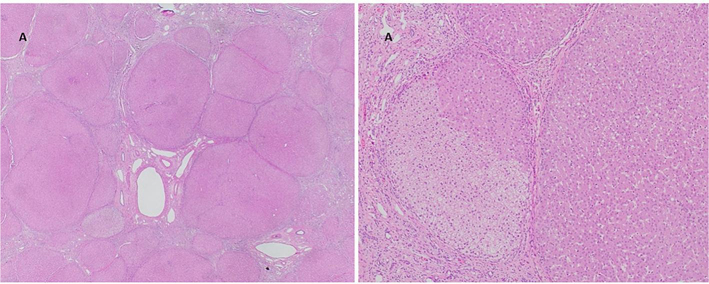

Due to progressive complications of end-stage liver disease, at 4 years of age our patient underwent deceased donor orthotopic liver transplant. The explanted liver demonstrated gross evidence of diffuse macronodular cirrhosis (Figure 1C). Histologic examination of the explanted liver revealed cirrhotic morphology with minimal macrovesicular steatosis and a few foci of glycogen-rich hepatocytes, without evidence of significant inflammation or biliary tract abnormalities (Figure 2). The post-operative period was complicated by ileal perforation with secondary bacterial peritonitis and chylous ascites requiring surgical repair and intravenous antibiotics. She suffered another stroke-like episode which resolved within a few days. Her immunosuppression regimen consisted of prednisone, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil, although mycophenolate was subsequently held and ultimately discontinued due to infection.

Figure 2.

(A) The explanted liver from the PMM2-CDG patient shows the formation of numerous nodules, consistent with established cirrhosis (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification x20). (B) A focus of glycogen-rich hepatocytes characterized by abundant clear cytoplasm (left side of image) and minimal macrovesicular steatosis (right side of image) (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification x100).

Within 1 month post-transplant, her elevated aminotransferases and coagulation abnormalities (namely, decreased activities of glycosylated coagulation factors) resolved (Table 1). Her jejunal feeding tube was eventually removed and she transitioned successfully first to continuous, then bolus gastric tube feeds with reintroduction of solid food without further episodes of diarrhea or hypoglycemia. Her weight increased from <1st percentile prior to transplant to 5th percentile upon 3-year follow-up; height remained between the 1st to 2nd percentile during the same period. Of note, at 5 years of age, she developed generalized seizures which were well-controlled with medication.

She remained on tacrolimus monotherapy for immune suppression. Liver allograft biopsy at 4 months and 1 year showed focal periportal inflammation without evidence of acute cellular rejection. Post-transplant she had recurrent infections 3–5 times per year, including acute episodes of Clostridioides difficile colitis treated with oral vancomycin and rotavirus gastroenteritis treated with oral immunoglobulins, COVID-19 infection without severe clinical symptoms, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection complicated by superimposed bacterial pneumonia, and recurrent bacterial upper airway and chronic ear infections. The frequency of her community-acquired infections somewhat decreased after the first year post-transplant in conjunction with increasing immunoglobulin levels.

After recovering from her post-operative complications, the patient acquired better head and trunk control and improved in both gross and fine motor coordination. She started to drink from a sippy cup for the first time in her life a few weeks after transplantation. Her alertness and attention improved. She started to scoot-crawl 2 years after transplant. However, she remained non-verbal, unable to sit without support, and unable to transfer objects from hand to hand. Formal neurodevelopmental assessment at baseline (chronological age 4 years) was consistent with a developmental age of <6 months, whereas at 5 months post-transplant (age 5 years) her developmental age was consistent with 6–12 months, and at 18 months post-transplant (age 6 years) with 8–18-months. At 3 years post-transplant (age 8 years), she was diagnosed with severe intellectual disability but continues to make growth and developmental progress (Figure 1B).

3.2. NPCRS and ICARS scores

At the time of liver transplant, our patient demonstrated a severe CDG phenotype, with a total NPCRS score of 40, based on a Section I score of 18, Section II score of 7, and Section III score of 15. At 12 months her total NPCRS score was 32, based on a Section I score of 16, Section II score of 4, and Section III score of 12. At 24 months, her total NPCRS score was 31, based on a Section I score of 16, Section II score of 3, and Section III score of 12. At 36 months her total NPCRS score was 30, based on a Section I score of 15, Section II score of 2, and Section III score of 13. Her full NPCRS scores pre- and post-transplant are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Nijmegen Pediatric CDG Rating Scale (NPCRS) scores in PMM2-CDG patient pre- and 36 months post-transplant.

| NPCRS | Pre-transplant | Post-transplant |

|---|---|---|

| Section I: Current Function | ||

| 1. Vision | + | + |

| 2. Hearing | + | ++ |

| 3. Communication | +++ | +++ |

| 4. Feeding | +++ | ++ |

| 5. Self-care | +++ | +++ |

| 6. Mobility | +++ | ++ |

| 7. Educational attainment | +++ | ++ |

| Section II: System Specific Involvement | ||

| 1. Seizures | − | − |

| 2. Encephalopathy | − | − |

| 3. Bleeding diathesis or coagulation defects | + | − |

| 4. Gastrointestinal | + | − |

| 5. Endocrine | ++ | − |

| 6. Respiratory | − | − |

| 7. Cardiovascular | − | + |

| 8. Renal | − | − |

| 9. Liver | +++ | − |

| 10 Blood | + | + |

| Section III: Current Clinical Assessment | ||

| 1. Growth | + | − |

| 2. Development over preceding 6 months | +++++ | +++++ |

| 3. Vision | − | + |

| 4. Strabismus and eye movement | ++ | + |

| 5. Myopathy | +++ | + |

| 6. Ataxia | ++ | ++ |

| 7. Pyramidal | − | + |

| 8. Extrapyramidal | + | − |

| 9. Neuropathy | + | ++ |

| NPCRS score summary | ||

| Section I: Current Function (maximum: 21) | 17 | 15 |

| Section II: System Specific Involvement (maximum: 30) | 8 | 2 |

| Section III: Current Clinical Assessment (maximum: 31) | 15 | 14 |

| Total NPCRS score (maximum 82) | 40 | 30 |

Grey bars show improvement in symptoms. (Note post-transplant progression in visual loss, neuropathy and pyramidal symptoms.)

Prior to liver transplant, her total ICARS score was 99/100, based on Posture and Gait Score of 34, Kinetic Score of 52, Dysarthria Score of 8, and Oculomotor Movement Score of 5. Currently, 36 months post-transplant, her total ICARS score improved to 92/100, based on Posture and Gait Score of 34, Kinetic Score of 49, Dysarthria Score of 8, and Oculomotor Movement Score of 3.

In summary, NPCRS scores improved in multisystem involvement, growth, nutrition, and muscle strength and function; however, ICARS scores showed only minimal improvement for eye contact, tracking, and muscle function and no benefit for coordination or ataxia.

3.3. Pre and post-transplant assessment of carbohydrate deficient transferrin analysis

Our patient’s transferrin glycoforms, including disialo- to tetrasialo- and asialo- to tetrasialo-transferrin ratios, measured by mass spectrometry (MS), normalized rapidly in our patient post-transplant. Carbohydrate deficient transferrin analysis was normal at 14 days and remained normal at 36 months (Table 2). Due to normalization of the transferrin profile, we performed additional quantitative N-glycan analysis for fractionated glycans of the PMM2 post liver transplant samples.

3.4. Quantitative N-glycan analysis

Transferrin N-glycans normalized within 5 months post-transplant in serum by quantitative N-glycan analysis. However, immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA and IgM) remained low in the first 5 months post-transplant, which made IgG N-glycan analysis unreliable. Eighteen months post-liver transplant, transferrin N-glycans were essentially normal, but the total IgG N-glycan profile remained abnormal, with increased Man3/4 and Man4/9 ratios and Man1/Gal1GlcNAc2 and GlcNAc2 (Man0) abundance. IgG glycosylation remained abnormal after liver transplant with reduced Man8 and Man9 abundance. Man9/3 ratio was reduced compared to non-CDG post-liver transplant controls and healthy controls. Interestingly, Man1/Gal1GlcNAc2 is also slightly increased in IgG N-glycans (Table 4). In the other protein fraction comprising the total plasma glycoproteins with the transferrin and IgG fractions removed, Man3/4 ratio is increased with reduced Man5 and Man6, suggesting that some glycoproteins enriched with Man5 and Man6 are likely only partially produced in the liver.

Table 4.

Fractionated serum N-glycoprotein analysis 1.5 years post-liver transplant.

| N-glycans (% total) | Man0 | Man1/G all |

Tetra d |

Man2 | Man3 | Man4 | Man5 | Man6 | Man7 | Man8 | Man9 | Man3/4 | Man9/3 | Man4/9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycan structure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ratio | Ratio | Ratio |

|

Plasma total

glycoprotein Normal Refrange (n=105) |

0.01 – 0.07 | 0.01 – 0.10 | 0.0 – 0.05 | 0.0 – 0.24 | 0.02 – 0.42 | 0.22 – 1.20 | 0.81 – 3.13 | 0.92 – 3.11 | 0.24 – 1.09 | 0.35 – 1.33 | 0.41 – 1.18 | 0.21 – 0.38 | 1.54 – 6.11 | 0.53 – 1.31 |

| PMM2 Post Liver transplant | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.79 | 1.37 | 2.68 | 2.67 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 2.08 |

|

IgG

fraction Normal Refrange (n=41) |

0.01 – 0.03 | 0.02 – 0.06 | 0 – 0.05 | 0.02 – 0.13 | 0.03 – 0.17 | 0.04 – 0.12 | 0.08 – 0.26 | 0.11 – 0.48 | 0.06 – 0.15 | 0.09 – 0.26 | 0.09 – 0.30 | 0.21 – 2.89 | 0.71 – 4.78 | 0.14 – 0.85 |

|

Non CDG Post transplant range (n=3) |

0.02 – 0.03 | 0.04 – 0.04 | 0.01 – 0.02 | 0.05 – 0.10 | 0.07 – 0.10 | 0.06 – 0.11 | 0.17 – 0.30 | 0.14 – 0.34 | 0.07 – 0.22 | 0.23 – 0.36 | 0.20 – 0.28 | 0.91 – 1.67 | 2.00 – 3.57 | 0.28 – 0.39 |

| PMM2 Post Liver transplant | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.0 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 1.86 | 0.69 | 0.78 |

|

Remainin g Plasma glycoprot ein

fraction Normal Ref range (n=41) |

0.02 – 0.05 | 0.04 – 0.08 | 0.0 – 0.03 | 0.09 – 0.20 | 0.21 – 0.49 | 0.65 – 1.58 | 1.64 – 4.04 | 1.30 – 2.98 | 0.35 – 0.83 | 0.36 – 0.80 | 0.43 – 1.02 | 0.28 – 0.33 | 1.26 – 4.06 | 0.68 – 2.29 |

| Non CDG Post transplant range (n=3) | 0.02 – 0.04 | 0.04 – 0.09 | 0.0 – 0.01 | 0.09 – 0.14 | 0.24 – 0.30 | 0.79 – 1.01 | 2.11 – 2.73 | 1.77 – 2.40 | 0.56 – 1.06 | 0.62 – 1.06 | 0.70 – 0.92 | 0.30 – 0.30 | 2.33 – 3.17 | 1.04 – 1.44 |

| PMM2 Post Liver transplant | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.72 | 1.54 | 1.22 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 1.63 | 1.07 |

While transferrin glycosylation is normalized post liver transplant, plasma N-glycan profile remains abnormal with increased Man3/4 and Man4/9 ratios and Man1/Gal1GlcNAc2 and GlcNAc2 (Man0) abundance. IgG glycosylation remains abnormal after the liver transplant with reduced Man8 and Man9 abundance. Man9/3 ratio is reduced comparing to non-CDG post liver transplant control or normal controls. Interestingly, Man1/Gal1GlcNAc2 is also slightly increased in IgG glycan. In the other protein fraction that comprises the total plasma glycoproteins with Tf and IgG removed, Man3/4 ratio is increased with reduced Man5 and Man6 suggesting some glycoproteins enriched with Man5 and Man6 are likely only partially produced by liver. Comparing non-CDG patients post liver transplant to normal controls, Man5–9 are high in both IgG and the other protein fraction, suggesting an upregulation of glycan extension post liver transplant potentially due to immune suppression. In the IgG fraction, Man8 and Man9 are particularly biased high potentially due to immune suppression. Overall glycosylation from other tissues remains mildly abnormal.

Comparing N-glycan profiles from non-CDG patients post-liver transplant to those of healthy controls, Man5–9 are increased in both the IgG and remaining protein fractions in non-CDG post-transplant controls, suggesting that glycan extension is upregulated after liver transplant. It is known that glycan extension occurs during the unfolded protein response (UPR) due to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (Sun et al., 2013). Therefore, it is possible that increased Man5–9 may be related to the use of immune suppression after transplant. In the IgG fraction, Man8 and Man9 are particularly biased high. It is known that neutral glycans on IgG reduce the half-life of IgG in circulation, possibly a downstream effect from immune suppressing drugs. Overall glycosylation from other tissues remains mildly abnormal (Table 4).

In summary, liver transplant did not completely correct glycosylation on IgG and on a small fraction of other extrahepatic glycoproteins in plasma.

4. DISCUSSION

The liver is an important site of protein glycosylation and is responsible for the synthesis of most serum glycoproteins. Many of the multiorgan manifestations observed in congenital disorders of glycosylation, including coagulopathy and endocrine abnormalities, are the direct result of defective hepatic N-glycosylation. In addition, liver dysfunction is observed in about one-fifth of CDG, ranging in severity from mild asymptomatic liver aminotransferase elevations and hepatomegaly to progressive hepatic fibrosis resulting in cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease (Marques-da-Silva et al., 2017).

The prevalence of liver abnormalities in PMM2-CDG in published series ranges from 42–100 percent. Mild findings, including hepatomegaly and elevated aminotransferases, are commonly reported (Kjaergaard et al., 2001, de Lonlay et al., 2001, Schiff et al., 2017, Witters et al., 2018, Starosta et al., 2021). Liver disease in most patients remains stable or improves over time (Arnoux et al., 2008, Schiff et al., 2017, Witters et al., 2018), and rarely progresses to liver failure (de Lonlay et al., 2001, Schiff et al., 2017). Liver biopsy, when performed, often shows hepatic steatosis or fibrosis (de Lonlay et al., 2001, Aronica et al., 2005, Choi et al., 2015, Schiff et al., 2017, Starosta et al., 2021), although this likely reflects a subset of patients with more severe liver involvement. Liver failure leading to death in infancy or early childhood has been described in a few patients (de Lonlay et al., 2001).

Successful liver transplantation for end-stage liver disease in CDG has been previously performed in one patient with MPI-CDG (Jansen et al., 2014) and one patient with CCDC115-CDG (Jansen et al., 2016). In the MPI-CDG patient, transplant resulted in resolution of gastrointestinal symptoms, enhanced nutritional status, and improved exercise tolerance. Biochemically, her coagulation parameters and transferrin profile completely normalized, although as expected, phosphomannose isomerase activity in leukocytes and IgG (a glycoprotein of extrahepatic origin) glycosylation remained abnormal (Jansen et al., 2014). In CCDC115-CDG, a pair of siblings received liver transplants but unfortunately the brother rejected the allograft twice and ultimately died of liver failure. Post-transplant, the sister did well and her elevated aminotransferases and transferrin profile normalized (Jansen et al., 2016). A patient with COG6-CDG with liver failure was also transplanted but died due to complications from the procedure (Rymen et al., 2015).

Herein, we report the first successful liver transplantation in PMM2-CDG. As demonstrated by our patient’s post-transplant outcomes, liver transplant promotes improved growth and development as well as complete restoration of secretory (hepatic) glycosylation, as indicated by normal liver synthetic function, coagulation factors, endocrine function, and transferrin isoform pattern. Notably, her chronic diarrhea and recurrent hypoglycemia also resolved, feeding difficulties improved, oral feeding became possible, and factor XI and antithrombin activities normalized. Perhaps most strikingly, her carbohydrate deficient transferrin profile showed evidence of improvement only 2 days after transplant, and by 14 days post-transplant had completely normalized (Table 2). Unsurprisingly, while indicators of hepatic glycosylation improved after transplant, IgG glycosylation, which occurs outside the liver in cells of the immune system (Arnold et al., 2007), remained abnormal (Table 4). Although immune suppression likely played a role in her recurrent infections post-transplant, persistent abnormal IgG glycosylation may have also been a contributing factor.

As suggested by our patient’s post-transplant developmental progression and improved cognition and motor coordination, liver transplant may have benefits on cognitive function and development for patients with PMM2-CDG, although the mechanisms by which this may occur and long-term post-transplant neurologic outcomes have yet to be determined. Improved post-transplant cognitive and psychomotor function may also arise at least in part from reduced disease burden and improved nutritional status. Studies of pediatric liver transplant populations have demonstrated that neurocognitive dysfunction is common pre-transplant and improves after transplant, though long-term intellectual and academic deficits often persist (Sun et al., 2019, Kennard et al., 1999, Sorensen et al. 2014). Clearly, transplant cannot fully reverse the neurodevelopmental, neurologic (coordination, fine motor function, ataxia) and structural brain abnormalities (namely, cerebellar hypoplasia), hearing loss, or peripheral neuropathy already present. One could hypothesize that an earlier therapeutic intervention restoring glycosylation in the whole body could be more impactful to improve CNS function. Overall, our patient’s encouraging post-transplant outcomes demonstrate that patients with PMM2-CDG with liver failure should not be excluded from consideration of liver transplant solely on the basis of their underlying diagnosis.

Recurrent respiratory infections are common problems in children with PMM2-CDG, especially within the first 4 years of life. This is a common cause of early mortality in patients, and may precipitate severe complications such as seizures, stroke-like episodes, or regression. However, only a minority of patients with PMM2-CDG have demonstrated laboratory evidence of immune dysfunction, such as hypogammaglobulinemia, T lymphopenia, or reduced neutrophil chemotaxis. As serum immunoglobulins are N-glycosylated, altered IgG function due to abnormal glycosylation has been suggested as one of the possible etiologies for increased vulnerability to infection and abnormal response to vaccination in several cases (Pascoal et al., 2020).

5. CONCLUSION

Our report is the first demonstration of an effective treatment for PMM2-CDG targeting the underlying biochemical defect. Given the current lack of other curative therapies for this disorder, patient’s post-transplant course supports the consideration of liver transplantation for PMM2-CDG patients with complications from end-stage liver disease. Persistent abnormal IgG glycosylation however may increase the risk of recurrent infections in patients after transplant.

Highligts:

Here we report on the first successful liver transplantation in PMM2-CDG, suggesting that liver transplantation should be considered as a treatment option for PMM2-CDG patients with end-stage liver disease. Besides the clear clinical and laboratory improvement we detected abnormal IgG glycosylation in our patient, which might play an additional role in the recurrent bacterial infections post-transplant.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge our patient and her family for participating in this research and expanding our knowledge about PMM2-CDG, and express special thanks to Carlie Lovejoy, RN.

Funding:

This research was funded by the grant entitled Frontiers in Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (1U54NS115191-01) from the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) and the Rare Disorders Consortium Disease Network (RDCRN), at the National Institute of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- CCDC115-CDG

CCDC115-congenital disorder of glycosylation

- CDG

congenital disorder of glycosylation

- CDT

carbohydrate-deficient transferrin

- COG6-CDG

COG6-congenital disorder of glycosylation

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FCDGC

Frontiers in Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation

- GGT

gamma-glutamyl transferase

- GlcNAc

N-acetylglucosamine

- ICARS

International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- INR

International Normalized Ratio

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- MPI-CDG

phosphomannose isomerase-congenital disorder of glycosylation

- NPCRS

Nijmegen Pediatric CDG Rating Scale

- PMM2-CDG

phosphomannomutase-2-congenital disorder of glycosylation

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- TSH

thyroid-stimulating hormone

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- WBC

white blood cell

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors Shawn Tahata, MD, Jody Weckwerth, PA-C, Anna Ligezka, Miao He, PhD, Hee Eun Lee, MD, PhD6 Julie Heimbach, MD, Samar H Ibrahim, M.B.Ch.B, Tamas Kozicz, MD PhD, Katryn Furuya, MD, Eva Morava, MD, PhD have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ferreira CR, Altassan R, Marques-Da-Silva D, Francisco R, Jaeken J, Morava E. Recognizable phenotypes in CDG. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 2018. May 1;41(3):541–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedade A, Francisco R, Jaeken J et al. Epidemiology of congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG)—overview and perspectives. J Rare Dis 1, 3 (2022). 10.1007/s44162-022-00003-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witters P, Honzik T, Bauchart E, Altassan R, Pascreau T, Bruneel A, Vuillaumier S, Seta N, Borgel D, Matthijs G, Jaeken J. Long-term follow-up in PMM2-CDG: are we ready to start treatment trials?. Genetics in Medicine. 2018. May;21(5):1181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer SW, Johnsen C & Morava E Nutrition interventions in congenital disorders of glycosylation. Trends Mol Med 28, 463–481, doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2022.04.003 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Čechová A, Honzík T, Edmondson AC, Ficicioglu C, Serrano M, Barone R, De Lonlay P, Schiff M, Witters P, Lam C, Patterson M, Janssen MCH, Correia J, Quelhas D, Sykut-Cegielska J, Plotkin H, Morava E, Sarafoglou K. Should patients with Phosphomannomutase 2-CDG (PMM2-CDG) be screened for adrenal insufficiency? Mol Genet Metab. 2021. Aug;133(4):397–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quelhas D, Carneiro J, Lopes-Marques M, Jaeken J, Martins E, Rocha JF, Teixeira Carla SS, Ferreira CR, Sousa SF, Azevedo L. Assessing the effects of PMM2 variants on protein stability. Mol Genet Metab. 2021. Dec;134(4):344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnewich D, O’Brien K, Sparks S. Clinical features in adults with congenital disorders of glycosylation type Ia (CDG-Ia). InAmerican Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics 2007. Aug 15 (Vol. 145, No. 3, pp. 302–306). Hoboken: Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefeber DJ, Morava E, Jaeken J. How to find and diagnose a CDG due to defective N-glycosylation. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease: Official Journal of the Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism. 2011. Aug;34(4):849–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witters P, Cassiman D, Morava E. Nutritional therapies in congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG). Nutrients. 2017. Nov;9(11):1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasil S, Pascoal C, Francisco R, Marques-da-Silva D, Andreotti G, Videira PA, Morava E, Jaeken J, dos Reis Ferreira V. CDG therapies: from bench to bedside. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018. May;19(5):1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lonlay P, Seta N. The clinical spectrum of phosphomannose isomerase deficiency, with an evaluation of mannose treatment for CDG-Ib. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2009. Sep 1;1792(9):841–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksz CJ, McClean P, Henderson MJ, Keir DG, Worthington VC, Imtiaz F, Schollen E, Matthijs G, Winchester BG. Successful treatment of carbohydrate deficient glycoprotein syndrome type 1b with oral mannose. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2001. Oct 1;85(4):339–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal V, Kjaergaard S, Davis JA, Peterson SM, Skovby F, Freeze HH. Genetic and metabolic analysis of the first adult with congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ib: long-term outcome and effects of mannose supplementation. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2001. May 1;73(1):77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panneerselvam K, Freeze HH. Mannose corrects altered N-glycosylation in carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome fibroblasts. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996. Mar 15;97(6):1478–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush JS, Panneerselvam K, Waechter CJ, Freeze HH. Mannose supplementation corrects GDP-mannose deficiency in cultured fibroblasts from some patients with Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (CDG). Glycobiology. 2000. Jan 1;10(8):829–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayatepek E, Schröder M, Kohlmüller D, Bieger WP, Nützenadel W. Continuous mannose infusion in carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type I. Acta Pædiatrica. 1997. Oct;86(10):1138–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayatepek E, Kohlmüller D. Mannose supplementation in carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type I and phosphomannomutase deficiency. European Journal of Pediatrics. 1998. Jun 1;157(7):605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaergaard S, Kristiansson B, Stibler H, Freeze HH, Schwartz M, Martinsson T, Skovby F. Failure of short-term mannose therapy of patients with carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type 1A. Acta Pædiatrica. 1998. Aug;87(8):884–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achouitar S, Mohamed M, Gardeitchik T, Wortmann SB, Sykut-Cegielska J, Ensenauer R, de Baulny HO, Õunap K, Martinelli D, de Vries M, McFarland R. Nijmegen paediatric CDG rating scale: a novel tool to assess disease progression. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 2011. Aug;34(4):923–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligezka AN et al. Patient-reported outcomes and quality of life in PMM2-CDG. Mol Genet Metab 136, 145–151, doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2022.04.002 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouillas P, Takayanagi T, Hallett M, Currier RD, Subramony SH, Wessel K, Bryer A, Diener HC, Massaquoi S, Gomez CM and Coutinho P, 1997. International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale for pharmacological assessment of the cerebellar syndrome. Journal of the neurological sciences, 145(2), pp.205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi H, Daniel EJP, Thies J, Chang I, Goldner DL, Ng BG, Witters P, Aqul A, Velez-Bartolomei F, Enns GM and Hsu E, Fractionated plasma N-glycan profiling of novel cohort of ATP6AP1-CDG subjects identifies phenotypic association. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen G, Muskiet FA, Schierbeek H, Berger R, van der Slik W. Capillary gas chromatographic profiling of urinary, plasma and erythrocyte sugars and polyols as their trimethylsilyl derivatives, preceded by a simple and rapid prepurification method. Clinica Chimica Acta. 1986. Jun 30;157(3):277–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li X, Edmondson A, Meyers GD, Izumi K, Ackermann AM, Morava E, Ficicioglu C, Bennett MJ, He M. Increased Clinical Sensitivity and Specificity of Plasma Protein Glycan Profiling for Diagnosing Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation by Use of Flow Injection-Electrospray Ionization-Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2019. May;65(5):653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Raihan MA, Reynoso FJ, He M. Glycosylation Analysis for Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2015. Jul 1;86:17.18.1–17.18.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Zhao Y, Zhou K, Freeze HH, Zhang YW and Xu H, 2013. Insufficient ER-stress response causes selective mouse cerebellar granule cell degeneration resembling that seen in congenital disorders of glycosylation. Molecular brain, 6, pp.1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques-da-Silva D, Dos Reis Ferreira V, Monticelli M, Janeiro P, Videira PA, Witters P, Jaeken J, Cassiman D. Liver involvement in congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG). A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 2017. Mar 1;40(2):195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lonlay P, Seta N, Barrot S, Chabrol B, Drouin V, Gabriel BM, Journel H, Kretz M, Laurent J, Le Merrer M, Leroy A. A broad spectrum of clinical presentations in congenital disorders of glycosylation I: a series of 26 cases. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2001. Jan 1;38(1):14–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff M, Roda C, Monin ML, Arion A, Barth M, Bednarek N, Bidet M, Bloch C, Boddaert N, Borgel D, Brassier A. Clinical, laboratory and molecular findings and long-term follow-up data in 96 French patients with PMM2-CDG (phosphomannomutase 2-congenital disorder of glycosylation) and review of the literature. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2017. Dec 1;54(12):843–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starosta RT, Boyer S, Tahata S, Raymond K, Lee HE, Doederlein Schwartz IV, Morava E. Liver manifestations in a cohort of 39 patients with congenital disorders of glycosylation: pin-pointing the characteristics of liver injury and proposing recommendations for follow-up. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2021. Jan 7;16(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnoux JB, Boddaert N, Valayannopoulos V, Romano S, Bahi-Buisson N, Desguerre I, De Keyzer Y, Munnich A, Brunelle F, Seta N, Dautzenberg MD. Risk assessment of acute vascular events in congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ia. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2008. Apr 1;93(4):444–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronica E, van Kempen AA, Van der Heide M, van Slooten HJ, Troost D, Rozemuller-Kwakkel JM. Congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ia: a clinicopathological report of a newborn infant with cerebellar pathology. Acta Neuropathologica. 2005. Apr 1;109(4):433–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi R, Woo HI, Choe BH, Park S, Yoon Y, Ki CS, Lee SY, Kim JW, Song J, Kim DS, Kwon S. Application of whole exome sequencing to a rare inherited metabolic disease with neurological and gastrointestinal manifestations: a congenital disorder of glycosylation mimicking glycogen storage disease. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2015. Apr 15;444:50–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen MC, De Kleine RH, Van Den Berg AP, Heijdra Y, Van Scherpenzeel M, Lefeber DJ, Morava E. Successful liver transplantation and long-term follow-up in a patient with MPI-CDG. Pediatrics. 2014. Jul 1;134(1):e279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen JC, Cirak S, Van Scherpenzeel M, Timal S, Reunert J, Rust S, Pérez B, Vicogne D, Krawitz P, Wada Y, Ashikov A. CCDC115 deficiency causes a disorder of Golgi homeostasis with abnormal protein glycosylation. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2016. Feb 4;98(2):310–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rymen D, Winter J, Van Hasselt PM, Jaeken J, Kasapkara C, Gokçay G, Haijes H, Goyens P, Tokatli A, Thiel C, Bartsch O. Key features and clinical variability of COG6-CDG. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2015. Nov 1;116(3):163–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JN, Wormald MR, Sim RB, Rudd PM, Dwek RA. The impact of glycosylation on the biological function and structure of human immunoglobulins. Annual Review of Immunology. 2007. Apr 23;25:21–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoal C, Francisco R, Ferro T, Dos Reis Ferreira V, Jaeken J, Videira PA. CDG and immune response: From bedside to bench and back. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2020. Jan;43(1):90–124. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Jia L, Yu H, Zhu M, Sheng M and Yu W, 2019. The effect of pediatric living donor liver transplantation on neurocognitive outcomes in children. Annals of Transplantation, 24, p.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennard BD, Stewart SM, Phelan-McAuliffe D, Waller DA, Bannister M, Fioravani V and Andrews WS, 1999. Academic outcome in long-term survivors of pediatric liver transplantation. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP, 20(1), pp.17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen LG, Neighbors K, Martz K, Zelko F, Bucuvalas JC, Alonso EM and Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation (SPLIT) Research Group, 2014. Longitudinal study of cognitive and academic outcomes after pediatric liver transplantation. The Journal of pediatrics, 165(1), pp.65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]