Abstract

Background

Telehealth has the potential to improve health care access for patients but it has been underused and understudied for examining patients with substance use disorders (SUD). VA began distributing video-enabled tablets to veterans with access barriers in 2016 to facilitate participation in home-based telehealth and expanded this program in 2020 due to the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective

Examine the impact of VA's video-enabled telehealth tablets on mental health services for patients diagnosed with SUD.

Methods

This study included VA patients who had ≥1 mental health visit in the calendar year 2019 and a documented diagnosis of SUD. Using difference-in-differences and event study designs, we compared outcomes for SUD-diagnosed patients who received a video-enabled tablet from VA between March 15th, 2020 and December 31st, 2021 and SUD-diagnosed patients who never received VA tablets, 10 months before and after tablet-issuance. Outcomes included monthly frequency of SUD psychotherapy visits, SUD specialty group therapy visits and SUD specialty individual outpatient visits. We examined changes in video visits and changes in visits across all modalities of care (video, phone, and in-person). Regression models adjusted for several covariates such as age, sex, rurality, race, ethnicity, physical and mental health chronic conditions, and broadband coverage in patients' residential zip-code.

Results

The cohort included 21,684 SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients and 267,873 SUD-diagnosed non-recipients. VA's video-enabled tablets were associated with increases in video visits for SUD psychotherapy (+3.5 visits/year), SUD group therapy (+2.1 visits/year) and SUD individual outpatient visits (+1 visit/year), translating to increases in visits across all modalities (in-person, phone and video): increase of 18 % for SUD psychotherapy (+1.9 visits/year), 10 % for SUD specialty group therapy (+0.5 visit/year), and 4 % for SUD specialty individual outpatient treatment (+0.5 visit/year).

Conclusions

VA's distribution of video-enabled tablets during the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with higher engagement with video-based services for SUD care among patients diagnosed with SUD, translating to modest increases in total visits across in-person, phone and video modalities. Distribution of video-enabled devices can offer patients critical continuity of SUD therapy, particularly in scenarios where they have heightened barriers to in-person care.

Keywords: Telemedicine, Telehealth, Substance abuse, Substance use disorder, Alcohol use disorder, Opioid use disorder, VA tablet, VA iPad, VA telehealth, Smart devices, SUD care during COVID-19, SUD psychotherapy, SUD group therapy, SUD treatment visits, SUD video

Introduction

Prevalence of substance use disorders (SUD) and related adverse consequences such as overdoses and overdose-related deaths have been rising in the U.S. for the past several decades (Lin et al., 2019). Utilization of effective treatment for SUD remains low, with lack of access to medication and psychotherapy for SUD being a major factor (Lin et al., 2019). These issues of were exacerbated during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (Clair, Ijadi-Maghsoodi, Nazinyan, Gabrielian, & Kalofonos, 2021). During the pandemic, many chemical dependency treatment programs and clinics decreased availability of in-person visits, which widened the already large gap between patients with SUD who need treatment and those who have actually received treatment (Oesterle, Kolla, Risma, et al., 2020). Since group therapy has been the mainstay treatment option for decades for patients with SUD, measures such as social distancing, shelter in place, and treatment discontinuation during the pandemic generated a need for alternative approaches for treatment of SUD (Oesterle et al., 2020).

Telehealth has the potential to improve health care access for patients with SUD but it has been underused and understudied in this patient population (Lin, Fernandez, & Bonar, 2020). Telehealth interventions can be difficult to implement, especially in the SUD population (Oesterle et al., 2020). Widespread adoption of telehealth has historically also been hindered by complex reimbursement and regulatory barriers at the state and federal levels. During the pandemic, state and federal agencies loosened regulations governing telehealth use to improve access to care (Oesterle et al., 2020). However, given that these landmark regulatory changes may be temporary, there is lingering uncertainty about telehealth's role in future health care delivery (Oesterle et al., 2020). A study of over 15,000 outpatient behavioral health treatment facilities in the U.S. (excluding Veterans Health Administration (VA) facilities) found that 32 % of mental health facilities and 43 % of SUD treatment facilities did not offer telehealth in January 2021, approximately 1 year into the pandemic (Cantor et al., 2022). Additional studies are needed to assess telehealth acceptability and engagement among patients with SUD and their clinicians (Lin et al., 2019). Moreover, there is a need for rigorous observational studies that examine real-world use of telemedicine for SUD care while addressing potential confounding due to selection into telehealth (Lin et al., 2019).

As the country's largest integrated healthcare delivery system and the single largest provider of telehealth services and substance use treatment (Lin, Bohnert, Blow, et al., 2021), VA provides a unique opportunity to rigorously examine the impact of telehealth use among patients diagnosed with SUD. Veterans are an important at-risk population for studying SUD care, and VA studies using strong methodology can inform the current national and state policy debates about telehealth licensure laws. Given that prior research indicates patients' lack of access to technology is a prominent barrier to delivering telehealth care to patients with SUD (Lin, Pham, Zhu, et al., 2023), we focused on evaluating VA's expansion of its tablet distribution program during the COVID-19 pandemic to facilitate veterans' participation in home-based telehealth (Zulman, Wong, Slightam, et al., 2019). As of November 2022, there were over 132,000 VA tablets in circulation, with 81 % of all VA-issued tablets having been distributed during the pandemic.

To assess feasibility and acceptability of telehealth for SUD care when the access barrier of owning a smart device is eliminated, we examined the impact of VA-issued video telehealth tablets on the frequency of SUD outpatient care in a national cohort of veterans with an SUD diagnosis. We compared patients who received VA tablets with those who did not receive VA tablets, before and after tablet-receipt using difference-in-differences and event study designs, methods that significantly mitigate concerns about confounding or selection into telehealth interventions.

Data

Study cohort

The study cohort of SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients and SUD-diagnosed non-recipients included all VA patients who had ≥1 VA mental health care visit in the calendar year 2019 and had a documented SUD diagnosis in the year 2019 (SUD ICD-10 codes in Online Supplement). Data on VA patients and visits were obtained from VA's Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), a VA electronic health records repository. For the purposes of identifying our study cohort, mental health visits were identified using VA stop codes used for characterizing outpatient visits (Ferguson et al., 2021). Veterans were classified as tablet-recipients if they received tablets from VA between March 16th 2020 and December 31th 2021. To isolate associations with VA tablets issued during COVID-19, Veterans who received VA tablets outside this time period or received VA iPhones were excluded. We followed veterans through June 30th, 2021 (the most recent data available at the time of the study) allowing a 10-month post-tablet period for most veterans. To compare post-tablet outcomes to pre-tablet outcomes, we used a similar look-back period of 10 months pre-tablets.

This evaluation was designated by VA's Office of Rural Health as non-research quality improvement and was exempted from review by the Stanford institutional review board. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Intervention

Clinicians used VA's national standardized Digital Divide Consult to refer potentially eligible patients for VA's video-enabled tablets with data plans (Telehealth, n.d.). Consults were placed for veterans who could benefit from video-based visits but lacked affordable or quality internet connection or a video-capable device. Veterans were prioritized for receiving tablets if they had an access barrier such as transportation challenges, housing instability, or residing 30 or more miles away from a VA facility, or if they complex clinical needs such as a mental health condition or had a recent hospitalization (Telehealth, n.d.; VA Office of Public & Affairs, n.d.). If veterans were considered eligible after consultation, tablets were mailed to veterans. There were no official tablet distribution criteria related to broadband availability in the area or patients diagnosed with SUD, but it is possible that clinicians took these considerations into account when initiating consults for certain patients. Digital Divide consults could also be used to refer Veterans to low-cost internet services (Telehealth, n.d.). Data on tablet-recipients and tablet-shipment dates were obtained from VA's Denver Acquisitions and Logistics Center (Heyworth, Kirsh, Zulman, Ferguson, & Kizer, 2020; Zulman et al., 2019).

Outcomes

Outcomes examined included monthly frequency of SUD psychotherapy visits (occurring either in a VA specialty care setting or across the continuum of VA care), SUD group therapy visits in VA specialty SUD settings, and SUD individual outpatient visits in VA specialty SUD settings. We examined changes in video visits and changes in visits across all modalities of care (video, phone, and in-person) for these services among SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients vs. SUD-diagnosed non-recipients before and after tablet-receipt. SUD psychotherapy visits were defined using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and SUD diagnosis codes, following prior work (Gujral et al., 2022). SUD group therapy visits were visits for group evaluation, consultation, follow-up, and treatment provided by a VA facility's formal SUD Treatment Program (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, n.d.) and SUD individual outpatient visits were individual visits for evaluation, consultation, follow-up and treatment provided by the SUD Treatment Program. Individual visits were identified using VA stop code 513 and group therapy visits were identified using VA stop code 560, following prior work (Lin et al., 2021). Since SUD psychotherapy visits are defined using CPT codes and not VA stop codes, there may be some overlap between SUD psychotherapy visits and SUD individual and group outpatient visits (e.g. CPT code 90853 used to define psychotherapy covers group therapy) in some cases. We chose to examine all three measures to assure a more comprehensive capture of VA's SUD-specific care services using pre-defined VA performance measures consistent with prior work. The findings for one measure validates the pattern of findings for another measure. Video visits were identified using VA stop codes of 179, 648, and 679, which indicated clinic-to-home and clinic-to-other/non-VA settings video telehealth care (Ferguson et al., 2021).

Covariates

We adjusted all models for relevant patient and area characteristics including veterans' age, sex, race, number of physical and mental health chronic conditions (Ferguson et al., 2021; Fishman, Von Korff, Lozano, & Hecht, 1997; Ray, Collin, Lieu, et al., 2000; Yu, Ravelo, Wagner, et al., 2003), diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, Nosos risk adjustment score (risk score based on the Medicare risk adjustment with additional covariates for mental health and medication usage) (Wagner, Stefos, Moran, et al., 2016), VA priority-based enrollment categories (based on veterans' service-connected disabilities and other factors (Wang et al., n.d.; Ferguson et al., 2021)), marital status, homelessness, an indicator for high suicide risk based on VA's risk prediction algorithm (Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, 2017), rurality, distance to nearest VA primary care facility, broadband percent use in patients' zip-codes and monthly COVID-19 cases in patients' counties. To account for any remaining time-invariant difference between SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients and SUD-diagnosed non-recipients, we included an indicator for being a tablet-recipient. We also included month fixed effects to control for shocks or events of each month and fixed effects for patients' closest secondary care facility to control for any time-invariant facility characteristics. Month fixed effects helped account for the effect of the pandemic in any given month.

Age, sex, race, diagnoses, Nosos score (Wagner et al., 2016), VA priority-based and marital status were obtained from VA's CDW electronic health record data. Rurality and distances to patients' closest VA medical centers were obtained from VA's Planning Systems Support Group. Homelessness was defined using outpatient stop codes indicating use of VA's homeless services and diagnosis codes (Ferguson et al., 2021). Data on high suicide risk were obtained from VA's Program Evaluation Resource Center. Data on percent broadband usage in patients' zip-codes were obtained from Microsoft (Ferres, n.d.). Data on county-level COVID-19 cases were obtained from the New York Times (The New York Times, 2021).

Statistical analysis

First, we conducted a descriptive examination of pre- and post-COVID-19 outcome trends for SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients and SUD-diagnosed non-recipients from January 2018 through December 2021. This descriptive examination also showed generally parallel trends between tablet-recipients and non-recipients before the COVID-19 pandemic, which provided support for using difference-in-differences (DiD) and event study designs (Abouk, Pacula, & Powell, 2019; Liao, Gupta, Zhao, et al., 2021; Raifman, Bor, & Venkataramani, 2021) to compare visit frequency for SUD care among veterans who received VA's video-enabled tablets and veterans who never received VA video tablets, 10 months before and after tablet-shipment. DiD assumes tablet-recipients (treatment group) and non-recipients (control group) would have exhibited similar or parallel trends in the absence of VA-issued tablets and uses abrupt breaks in the parallel trends as a signal of associations with VA tablets. The methods are strengthened because we exploit variation in timing of tablet-shipment across veterans to isolate the effect of VA-issued tablets examining outcomes pre-post tablets. Recent developments show that event studies improve on the usual DiD estimator (Goodman-Bacon, 2018; Sun & Abraham, 2020; Wing, Simon, & Bello-Gomez, 2018) because they provide DiD estimates for each period pre- and post-tablets (Sun & Abraham, 2020; Wing et al., 2018), which allows us to visually assess whether there was any trending in differences pre-tablets that could obscure identification of true differences or associations post-tablets (Freyaldenhoven, Hansen, & Shapiro, 2019; Sun & Abraham, 2020; Wing et al., 2018). The absence of differences between tablet-recipients and non-recipients pre-tablets, followed by abruptly different and significant differences post-tablets signal attributability of the findings to tablets (Freyaldenhoven et al., 2019; Sun & Abraham, 2020; Wing et al., 2018). In this study, the intervention variable for event studies was “month-relative-to-tablet-shipment,” where shipment month was relative month “0.” We excluded relative months “−1” and “0” to avoid attributing tablet assignment- and setup-related visits to tablet-associated effects, making relative month “−2” (i.e. 2 months prior to tablet-shipment) the baseline month. For estimating usual DiD estimates, the intervention variable was the interaction between indicators for tablet-recipient and post-tablet (method details in Online Supplement).

We also conducted subgroup analyses to assess whether our results were vastly different across certain subgroups: patients who were ever or never homeless and for patients who were Black or lived in rural areas or far from VA facilities.

All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 17.0 (StataCorp, LLC).

Results

As indicated in Table 1 , the study cohort comprised 289,557 veteran patients (21,684 SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients and 267,873 SUD-diagnosed non-recipients). Compared to non-recipients, tablet-recipients were more likely to be homeless (27 % vs. 8 %), to have been classified by VA as high-risk for suicide (22 % vs. 12 %), and more likely to be Black or African American (38 % vs. 28 %). Recipients were also slightly older (mean age 56.7 vs. 52.2), more likely to be living in urban areas (77 % vs. 73 %), more likely to be diagnosed with depression (63 % vs. 56 %), and have a higher Nosos risk score (3.5 vs. 2.1). At baseline, tablet-recipients used more SUD care services (via video and across all modalities) than non-tablet-recipients. For SUD psychotherapy, 20.5 % of tablet-recipients had at least one visit compared to 9.4 % of non-recipients. For SUD group therapy and individual outpatient visits, 8.5 % and 13.2 % of tablet-recipients had at least one visit compared to 4.3 % and 6.8 %, respectively.

Table 1.

Unadjusted cohort characteristics at baseline, by tablet-recipient status.

| SUD tablet non-recipients, N (%) | SUD tablet-recipients, N (%) | P-valuesa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 267,873 | 21,684 | ||

| Outcomes | |||

| Any SUD Psychotherapy Visit (Y/N) | 25,284 (9.4 %) | 4441 (20.5 %) | <0.001 |

| Any Video SUD Psychotherapy Visit (Y/N) | 48 (0.02 %) | 1283 (5.9 %) | <0.001 |

| Any SUD Group Therapy Visit (Y/N) | 11,625 (4.3 %) | 1844 (8.5 %) | <0.001 |

| Any Video SUD Group Therapy Visit (Y/N) | 0 (0 %) | 578 (2.7 %) | <0.001 |

| Any SUD Individual Outpatient Visit (Y/N) | 18,093 (6.8 %) | 2866 (13.2 %) | <0.001 |

| Any Video SUD Individual Outpatient Visit (Y/N) | 13 (0.01 %) | 717 (3.3 %) | <0.001 |

| Covariates | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 243,995 (91 %) | 19,674 (91 %) | 0.078 |

| Female | 23,878 (9 %) | 2010 (9 %) | 0.078 |

| Age, mean | 52.2 (14.4) | 56.7 (11.9) | <0.001 |

| Homeless | 22,268 (8 %) | 5925 (27 %) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 71,322 (27 %) | 5066 (23 %) | |

| Distance to closest VA primary care site, mean | 13.3 (13.0) | 11.4 (12.1) | <0.001 |

| Number of Physical Chronic Conditions in 2019, mean | 4.0 (3.0) | 5.3 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Number of Mental Chronic Conditions, mean | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in 2019 | 126,919 (47 %) | 10,207 (47 %) | 0.38 |

| Diagnosed with Depression in 2019 | 150,038 (56 %) | 13,556 (63 %) | <0.001 |

| Nosos risk score | 2.1 (2.4) | 3.5 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| High-risk for suicideb | |||

| Never classified as high-risk | 233,883 (87 %) | 16,342 (75 %) | <0.001 |

| Classified as high-risk (but < top 1 % of risk) | 31,694 (12 %) | 4690 (22 %) | <0.001 |

| Classified as top 1 % of risk | 2296 (1 %) | 652 (3 %) | <0.001 |

| VA Priority-Based Enrollment Categories | |||

| 1 | 138,061 (52 %) | 8980 (41 %) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 17,503 (7 %) | 1306 (6 %) | 0.003 |

| 3 | 25,619 (10 %) | 2542 (12 %) | <0.001 |

| 4 | 8965 (3 %) | 1564 (7 %) | <0.001 |

| 5 | 54,631 (20 %) | 6297 (29 %) | <0.001 |

| 6 | 4252 (2 %) | 136 (1 %) | <0.001 |

| 7 | 4678 (2 %) | 260 (1 %) | <0.001 |

| 8 | 14,164 (5 %) | 599 (3 %) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 18,146 (7 %) | 959 (4 %) | <0.001 |

| Not Hispanic | 245,708 (92 %) | 20,445 (94 %) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 4019 (2 %) | 280 (1 %) | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4298 (2 %) | 337 (2 %) | 0.57 |

| Asian | 2612 (1 %) | 93 (<1 %) | <0.001 |

| Black or African American | 75,659 (28 %) | 8300 (38 %) | <0.001 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2676 (1 %) | 163 (1 %) | <0.001 |

| White | 182,628 (68 %) | 12,791 (59 %) | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Divorced | 82,659 (31 %) | 8340 (38 %) | <0.001 |

| Married | 93,222 (35 %) | 5039 (23 %) | <0.001 |

| Separated | 18,025 (7 %) | 1884 (9 %) | <0.001 |

| Widowed | 6005 (2 %) | 705 (3 %) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 2718 (1 %) | 108 (<1 %) | <0.001 |

Differences in proportions of dichotomous variables were tested using the Pearson's chi-squared test. Differences in means of continuous variables were tested using the two-sample t-test.

VA classifies Veterans as high-risk for suicide using VA's predictive model that analyzes existing data from Veterans' health records to identify statistically-elevated risk for suicide, hospitalization, illness or other adverse outcomes.

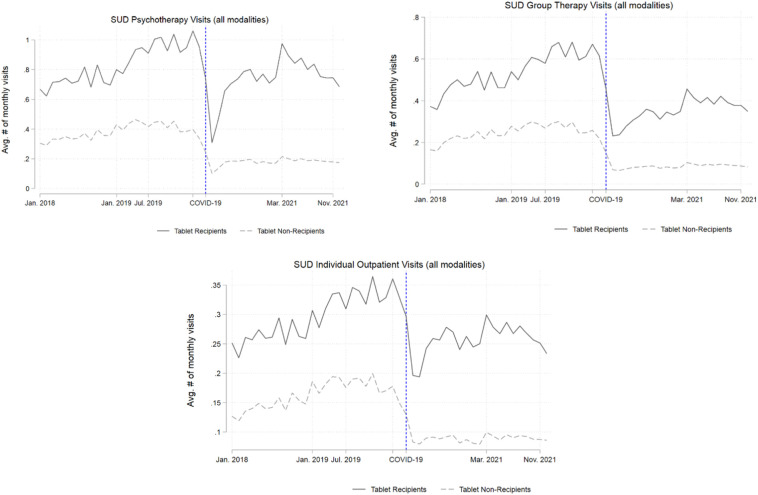

Fig. 1 shows that post-pandemic onset, both tablet-recipients and non-recipients experienced a drop in visits for SUD care (across all modalities), but the frequency of SUD care visits appeared to recover more for tablet-recipients than for non-recipients.

Fig. 1.

Unadjusted descriptive outcome trends for SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients and SUD-diagnosed non-recipients, pre- and post-pandemic onset.

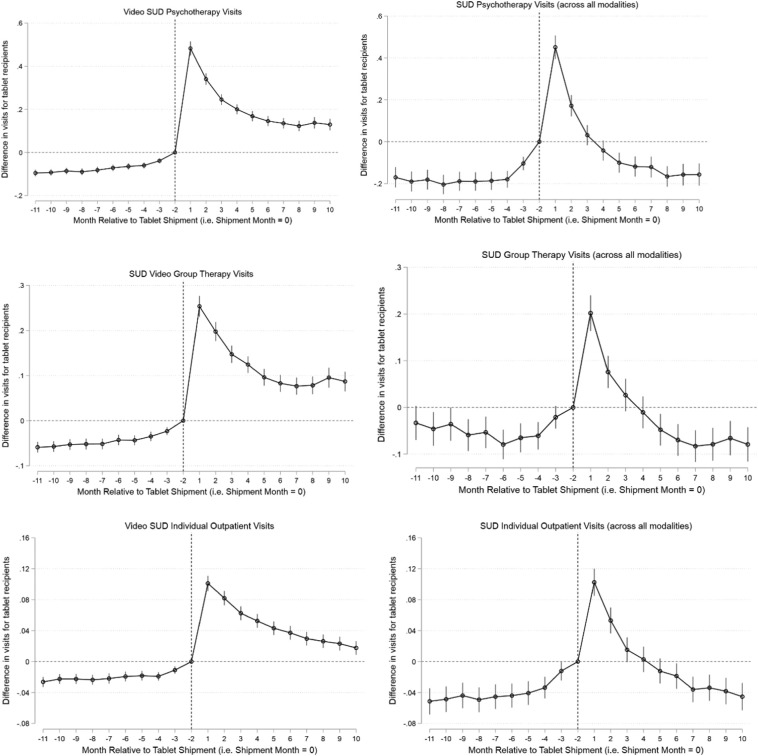

Fig. 2 shows that after adjusting for covariates, there were few differences and no trending in differences between tablet-recipients and non-recipients pre-tablets, but that there were abrupt changes in these patterns and significant increases in SUD care visits (via video and across all modalities) post-tablets.

Fig. 2.

Adjusted differences in frequency of visits (via video and across all modalities) for SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients (vs. recipients' baseline and SUD-diagnosed non-recipients) — event study estimates.

Note: We excluded months −1 and month 0 because treatment assignment i.e. tablet assignment likely occurred in these months and we did not want to attribute tablet assignment-related visits to the tablet-associated effects. All models adjusted for veterans' age, sex, race, number of physical and mental health chronic conditions, diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, Nosos risk adjustment score, VA priority-based enrollment, marital status, rurality, distance to VA primary care, homelessness indicator, high suicide risk indicator, cumulative monthly COVID-19 cases in the patient's county, and broadband availability in the patient's zip-code. All models included indicators for calendar month to adjust for events occurring in each month, indicators for patients' closest VA medical center to control for any time-invariant facility characteristics, and an indicator for being a tablet-recipient, which adjusted for any remaining fixed difference between tablet-recipients and non-recipients. In all models, standard errors accounted for clustering at the patient-level.

DiD estimates (Table 2 ) show that among this cohort of veteran patients diagnosed with SUD, tablets were associated with additional yearly increases of 3.5 video SUD psychotherapy visits and 1.9 SUD psychotherapy visits across all modalities including in-person, phone telehealth and video telehealth (18.1 % increase compared to baseline). Tablets were also associated with yearly increases of 2.1 video SUD group therapy visits and 0.8 video SUD individual outpatient visits, which translated to yearly increase of 0.5 SUD group visits and 0.5 SUD individual visits across all modalities (9.5 % and 14.4 % increase compared to baseline), respectively.

Table 2.

Adjusted differences in frequency of visits (via video and across all modalities) for SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients (vs. recipients' baseline and SUD-diagnosed non-recipients) — difference in-difference coefficients (& 95 % confidence intervals).

| SUD Video Psychotherapy | SUD Video Group Therapy | SUD Video Individual Outpatient Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TabletRecipienta | 0.036 (0.030: 0.043) |

0.021 (0.016: 0.026) |

0.011 (0.008: 0.013) |

| TabletRecipientb ∗ Post-Tablet | 0.289 (0.273: 0.306) |

0.171 (0.157: 0.185) |

0.069 (0.063: 0.075) |

| Baseline mean for tablet-recipients | 0.180 | 0.102 | 0.062 |

| % change from recipients' baselinec | 160.6 % | 167.6 % | 111.2 % |

| SUD Psychotherapy (across all modalities) | SUD Group Therapy (across all modalities) | SUD Individual Outpatient Treatment (across all modalities) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TabletRecipienta | 0.249 (0.228: 0.270) |

0.144 (0.128: 0.161) |

0.074 (0.066: 0.082) |

| TabletRecipientb ∗ Post-Tablet | 0.156 (0.130: 0.183) |

0.041 (0.021: 0.061) |

0.041 (0.031: 0.050) |

| Baseline monthly mean for tablet-recipients | 0.863 | 0.428 | 0.284 |

| % change from recipients' baselinec | 18.1 % | 9.5 % | 14.4 % |

| Number of veterans | 289,557 | 289,557 | 289,557 |

The coefficient on the variable “TabletRecipient” indicates the fixed difference between tablet-recipients and non-recipients.

The coefficient on “TabletRecipient ∗ Post-Tablet” represents difference-in-differences estimate, i.e. it averages the associations of tablets across all post-tablet months. These coefficients represent monthly changes in visits or in likelihood of visits. The monthly change in likelihood of visits is the same as an estimated yearly change in likelihood of visits. For outcomes looking at the number of visits, we multiply coefficients by 12 to estimate yearly changes in the number of visits reported in the paper.

To calculate the % change from baseline, we divided the difference-in-difference estimates described in table note b above by the baseline monthly mean for tablet-recipients reported in the table and multiplies by 100.

Findings were similar when we examined certain subgroups: patients who were ever or never homeless, patients who were Black, patients living in rural areas or living 20–40 miles from VA facilities (Online Supplement Tables C1–C5).

Discussion

To our best knowledge, this was the first and largest evaluation of the impact of distributing video telehealth tablets to patients diagnosed with SUD. Acknowledging that rigorous observational studies evaluating telehealth use among SUD patients are needed (Lin et al., 2019), we used strong empirical methods that can account for potential unobserved confounding and found that VA's video-enabled tablets were associated with sustained increases in video visits for SUD psychotherapy (+3.5 visits/year), SUD specialty group therapy (+2.1 visits/year) and SUD specialty individual outpatient treatment (+1 visit/year). These increases in video visits translated to modest increases in SUD care across all modalities (including in-person, phone, and video). Together, these patterns suggest that in many cases, video visits replaced in-person visits. Prior work has noted the clinical importance of such increases in psychotherapy (Gujral et al., 2022) and group therapy for SUD care (Oesterle et al., 2020) and the importance of continuation of SUD care when in-person services were declining (Oesterle et al., 2020). These results indicate that VA's distribution of tablets facilitated continuity of SUD care among tablet-recipients through video telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The longitudinal month-by-month nature of our analyses allowed us to also note that differences in SUD care visits between tablet-recipients and non-recipients declined over time after the initial issuance of tablets, a pattern broadly consistent with prior work evaluating VA tablets in a similarly long follow-up period (Gujral et al., 2022). Future studies should examine whether the decline in additional visits for tablet-recipients compared to non-recipients reflects a gradual decline in patient engagement with technology-based health care solutions noted by other studies (Beukenhorst, Howells, Cook, et al., 2020; Diehl, Barrett, Van Doorn, et al., 2022; Schaefer, Ching, Breen, & German, 2016) examining mobile applications, smartwatches and wearable technology because such a decline in engagement over time may have adverse long-term implications for patient care reliant on technological solutions.

Nonetheless, given that telehealth has been underused and understudied among patients diagnosed with SUD4 and because prior research has pointed to a lack of access to technology and to smart devices as a prominent barrier affecting telehealth use among patients with SUD (Lin et al., 2023), our findings of an average overall increase across the study period in engagement with video services and modest increases in SUD care visits across all modalities offer promising evidence of the acceptability of and engagement with telehealth use among SUD patients.

Limitations

A natural limitation of evaluating this health system intervention was that tablet-assignments were non-random. There were baseline differences between SUD-diagnosed tablet-recipients and SUD-diagnosed non-recipients; recipients were more likely to engage in use of SUD care services and had more clinical indicators for poor health. To address this, we leveraged the difference-in-differences study design which allows for such level differences between tablet-recipients and non-recipients and relies instead on parallel outcome trends across tablet-recipients and non-recipients; this method can handle unobservable drivers so long as unobserved confounders do not change at the same time as tablet-issuance occurs. Variation in tablet-shipment timing across veterans and our use of the event study design improved upon the traditional difference-in-difference approach (details in Statistical Analysis). We also provided visual evidence of parallel trends pre-pandemic (Fig. 1) and of an abrupt break from the pre-tablet to the post-tablet period (Fig. 2) that strengthens attributability of our findings to VA tablets. Furthermore, given concerns that baseline differences across tablet-recipients and non-recipients related to homelessness, racial differences, or distance from VA could lead to differential shocks at the time of tablet-receipt across certain subgroups, we demonstrated that the results persist even when we focused on subgroups of patients who were ever homeless, never homeless, racial minorities, or patients who lived in rural or areas far from VA (Online Supplement Tables C1–C5).

We focused on examining the impact of VA's telehealth tablets on VA SUD care and therefore did not capture instances of veterans receiving SUD care outside VA. Next, our definition of SUD psychotherapy visits (occurring either in specialty SUD settings or in the broader continuum of care) may at times include SUD group therapy and SUD individual treatment visits occurring in specialty care settings (details in Outcomes section), but we favored using all three pre-defined VA performance measures as they offer consistency with prior work and because the tablet-association patterns observed in one measure validate findings for the other measures. Next, we focused on examining tablets' impact on visit frequency, but not on SUD-specific health outcomes. Future work should examine the impact of VA tablets and telehealth on health outcomes among patients diagnosed with SUD. Given that evidence on whether telehealth is similar to in-person care for SUD outcomes is very uncertain and given that we do not yet fully understand the ramifications of the rapid switch to telehealth during the pandemic for patients with SUD (Lin et al., 2019; Mark et al., 2022; Oesterle et al., 2020; Uhl, Bloschichak, Moran, et al., 2022), it is critical to track how the substitution of in-person visits with video visits influences health outcomes among this population of patients.

Finally, as we focused on patients previously engaged in VA mental health care with a documented diagnosis of SUD, the results may not readily be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusions

VA and other health systems may consider strengthening their telehealth infrastructure, whether through smart device distribution or through other similar interventions that facilitate patient participation in video telehealth, to improve access to care for patients with substance use disorders.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs' Virtual Access QUERI Partnered Evaluation Initiative with VA's Office of Rural Health (ORH) (#PEI-18-205) and VA HSR&D Small Award Program (SWIFT) Locally Initiated Project (#LIP 22-KG-1). Josephine Jacobs, PhD, acknowledges support from a VA Career Development Award (#CDA-19-120). We are grateful to Samantha Illarmo, MPH, for research and administrative assistance. We are also thankful for our discussions with VA's Program Evaluation Resource Center (PERC) related to VA's substance use disorder care and outcome measures.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Concept and design: Gujral, Jacobs, Kimerling, Zulman, Blonigen.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Gujral.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Gujral, Van Campen, Jacobs, Kimerling, Blonigen, Zulman.

Statistical analysis: Gujral.

Obtained funding: Gujral, Zulman.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Gujral, Van Campen, Jacobs, Kimerling, Blonigen, Zulman.

Supervision: Gujral, Blonigen.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.josat.2023.209067.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Additional details.

STROBE checklist.

References

- Abouk R., Pacula R.L., Powell D. Association between state laws facilitating pharmacy distribution of naloxone and risk of fatal overdose. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019;179(6):805–811. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukenhorst A.L., Howells K., Cook L., et al. Engagement and participant experiences with consumer smartwatches for health research: Longitudinal, observational feasibility study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2020;8(1) doi: 10.2196/14368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor J., McBain R.K., Kofner A., Hanson R., Stein B.D., Yu H. Telehealth adoption by mental health and substance use disorder treatment facilities in the COVID-19 pandemic. PS. 2022;73(4):411–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clair K., Ijadi-Maghsoodi R., Nazinyan M., Gabrielian S., Kalofonos I. Veteran perspectives on adaptations to a VA residential rehabilitation program for substance use disorders during the novel coronavirus pandemic. Community Mental Health Journal. 2021;57:801–807. doi: 10.1007/s10597-021-00810-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl T.M., Barrett J.R., Van Doorn R., et al. Promoting patient engagement during care transitions after surgery using mobile technology: Lessons learned from the MobiMD pilot study. Surgery. 2022;172(1):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson J., Jacobs J., Yefimova M., Greene L., Heyworth L., Zulman D. JAMIA; 2021. Virtual care expansion in the Veterans Health Administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J Kahan JL Ferres n.d. Broadband usage percentages zip code dataset. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://github.com/microsoft/USBroadbandUsagePercentages.

- Fishman P., Von Korff M., Lozano P., Hecht J. Chronic care costs in managed care. Health Affairs. 1997;16(3):239–247. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyaldenhoven S., Hansen C., Shapiro J.M. Pre-event trends in the panel event-study design. American Economic Review. 2019;109(9):3307–3338. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Bacon A. The National Bureau of Economic Research; 2018. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. [Google Scholar]

- Gujral K., Van Campen J., Jacobs J., Kimerling R., Blonigen D., Zulman D.M. Mental health service use, suicide behavior, and emergency department visits among rural US veterans who received video-enabled tablets during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(4) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.6250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyworth L., Kirsh S., Zulman D., Ferguson J., Kizer K. NEJM Catalyst; 2020. Expanding access through virtual care: The VA’s early experience with covid-19. Published online. [Google Scholar]

- Liao J.M., Gupta A., Zhao Y., et al. Association between hospital voluntary participation, mandatory participation, or nonparticipation in bundled payments and medicare episodic spending for hip and knee replacements. JAMA Network Open. 2021;326(5):438–440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.10046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A., Fernandez A.C., Bonar E.E. Telehealth for substance-using populations in the age of coronavirus disease 2019. Recommendations to enhance adoption. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1209–1210. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C., Pham H., Zhu Y., et al. Telemedicine along the cascade of care for substance use disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2023;242 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.A., Bohnert A.S.B., Blow F.C., et al. Polysubstance use and association with opioid use disorder treatment in the US veterans health administration. Addiction. 2021;116(1):96–104. doi: 10.1111/add.15116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.A., Casteel D., Shigekawa E., Weyrich M.S., Roby D.H., SB M.M. Telemedicine-delivered treatment interventions for substance use disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2019;101:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark T.L., Treiman K., Padwa H., Henretty K., Tzeng J., Gilbert M. Addiction treatment and telehealth: Review of efficacy and provider insights during the COVID-19 pandemic. PS. 2022;73(5):484–491. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle T.S., Kolla B., Risma C.J., et al. Substance use disorders and telehealth in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2020;95(12):2709–2718. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs . VA.gov; 2017. VA REACH VET initiative helps save veterans lives: Program signals when more help is needed for at-risk veterans.https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=2878 [Google Scholar]

- Raifman J., Bor J., Venkataramani A. Association between receipt of unemployment insurance and food insecurity among people who lost employment during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(1) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35884. e2035884-e2035884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray G.T., Collin F., Lieu T., et al. The cost of health conditions in a health maintenance organization. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000 doi: 10.1177/107755870005700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer S.E., Ching C.C., Breen H., German J.B. Wearing, thinking, and moving: Testing the feasibility of fitness tracking with urban youth. American Journal of Health Education. 2016;47(1):8–16. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2015.1111174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Abraham S. Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Econometrics. 2020;225(2):175–199. [Google Scholar]

- VA Telehealth n.d. Bridging the digital divide. VA Telehealth. Accessed April 16, 2023. https://telehealth.va.gov/digital-divide.

- The New York Times . 2021. Coronavirus (Covid-19) data in the United States.https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Substance use disorder (SUD) program. https://www.va.gov/directory/guide/sud.asp

- Uhl S., Bloschichak A., Moran A., et al. Telehealth for substance use disorders: A rapid review for the 2021 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense guidelines for management of substance use disorders. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(5):691–700. doi: 10.7326/M21-3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. n.d. VA expands Veteran access to telehealth with iPad services. Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5521.

- Wagner T., Stefos T., Moran E., et al. Health Economics Resource Center; VA Palo Alto: 2016. Risk adjustment: Guide to the V21 and Nosos risk score programs technical report 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.Z., Dhanireddy P., Prince C., Larsen M., Schimpf M., Pearman G. Survey of veteran enrollees’ health and use of health care. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHPOLICYPLANNING/SOE2019/2019_Enrollee_Data_Findings_Report-March_2020_508_Compliant.pdf

- Wing C., Simon K., Bello-Gomez R.A. Designing difference in difference studies: Best practices for public health policy research. Annual Review of Public Health. 2018;39 doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W., Ravelo A., Wagner T.H., et al. Prevalence and costs of chronic conditions in the VA health care system. Medical Care Research and Review. 2003;60(3_suppl):146S–167S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703257000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulman D., Wong E., Slightam C., et al. Making connections: nationwide implementation of video telehealth tablets to address access barriers in veterans. JAMIA Open. 2019;2(3):323–329. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooz024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional details.

STROBE checklist.