Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Age-related cognitive decline is common and potentially modifiable with cognitive training. Combining cognitive training with pro-cognitive medication offers an opportunity to modify brain networks to mitigate age-related cognitive decline. We tested the hypothesis that the efficacy of cognitive training could be amplified by combining it with vortioxetine, a pro-cognitive and pro-neuroplastic multimodal antidepressant.

METHODS:

We evaluated effects of 6 months of computerized cognitive training plus vortioxetine (vs placebo) on resting state functional connectivity in older adults (age 65+) with age-related cognitive decline. We first evaluated the association of functional connectivity with age and cognitive performance (N=66). Then we compared effects of vortioxetine plus cognitive training versus placebo plus cognitive training on connectivity changes over the training period (n=20).

RESULTS:

At baseline, greater age was significantly associated with lower within-network strength and network segregation, and poorer cognitive function. Cognitive training plus vortioxetine over 6 months positively impacted the relationship of age to mean network segregation. These effects were not observed in the placebo group. In contrast, vortioxetine did not modify the relationship of age to change in mean within-network strength. Exploratory analyses identified the cingulo-opercular network as the network most affected by cognitive training plus vortioxetine.

CONCLUSIONS:

This preliminary study provides evidence that combining cognitive training with a pro-cognitive medication may modulate the effects of aging on functional brain networks. Results indicate that for older adults experiencing age-related cognitive decline, vortioxetine has a potentially beneficial effect on the correspondence between aging and functional brain network segregation. These results await replication in a larger sample.

Keywords: Cognitive training, cognitive decline, resting state functional connectivity, vortioxetine, aging, fMRI

INTRODUCTION

Age-related cognitive decline—normative progressive reduction in cognitive abilities with aging—affects a broad range of fluid cognition domains including memory, executive functioning, and information processing speed1. It is a heterogeneous phenomenon, likely reflecting multiple etiologies including Alzheimer and cerebrovascular diseases, as well as individual differences in neurocognitive resilience2,3. Despite this heterogeneity, age-related cognitive decline is potentially treatable. One putative intervention is cognitive training. Many clinical trials have implemented cognitive training protocols in older adults with varying degrees of efficacy4,5. These studies typically show low effect size and limited transfer beyond specific trained activities4,5. One potential approach to improve efficacy of cognitive training is combining it with medications that boost cognitive processing and neuroplasticity.

Our group has studied the effects of an intensive computerized cognitive training intervention in older adults with or without concurrent treatment with a putatively pro-cognitive and pro-neuroplastic medication6. Several trials have indicated that the novel multimodal antidepressant vortioxetine improves cognition in several domains7-10, although it is not currently FDA-approved for treatment of age-related cognitive decline. Unlike SSRIs and SNRIs, vortioxetine enhances excitatory synaptic neurotransmission and neuroplasticity11,12. Rodent models demonstrate that vortioxetine increases dendritic arborization13 and enhances signaling within multiple neurotransmitter systems that are essential for cognitive functioning12.

Cognitive training together with vortioxetine may boost resilience to cognitive decline by modifying brain networks. Sets of brain regions with temporally correlated spontaneous activity are thought to operate as functional networks14-18. Brain networks are most efficient and effective when network segregation is high, reflecting strong positive within-network connectivity coinciding with strongly negative between-network connectivity19-21. Numerous studies have demonstrated reduced within-network connectivity and segregation are associated with typical aging and Alzheimer’s disease19,22-24. Furthermore, network segregation during resting state positively correlates with resilience both to global cognitive decline and to memory impairment in individuals with mild Alzheimer pathology, underscoring the relationship between integrity of resting state networks and cognition in late life21. The strength of particular individual brain networks e.g., the default mode, frontoparietal, cingulo-opercular, salience, dorsal attention, ventral attention, medial temporal lobe, and parietal memory networks, may be additionally informative about the cognitive aging process14-16. Extensive and widespread changes arise in typical aging and Alzheimer’s disease within these individual networks as well as mean whole brain measures, attracting substantial efforts toward remediation.

To date there are only two published human functional neuroimaging (fMRI) studies of vortioxetine, and much is still unknown about its functional mechanisms of action. Evidence from non-depressed and remitted depressed young to midlife adults indicated that two weeks of vortioxetine significantly reduced brain activation during an N-back working memory task within dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and temporal-parietal regions, suggesting greater efficiency of mental processing after treatment25. The authors proposed that a course of vortioxetine may facilitate more effective disengagement from a default (i.e., in the absence of cognitive demands) network to engage regions necessary for successful task performance. The only published study of vortioxetine’s impact on resting state fMRI reported that 8 weeks of vortioxetine increased depressed young to midlife adults’ resting state amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF) in anterior cingulate and across prefrontal and temporal regions26, which may index elevated neuroplasticity particularly in these regions. The present study advances prior research to a significantly longer trial of vortioxetine plus computerized cognitive training in non-depressed older adults.

We previously reported successful behavioral effects of this intervention to remediate age-related cognitive decline6; 6 months of computerized cognitive training combined with vortioxetine significantly improved fluid cognition. However, the results left open questions about the neural changes underlying the overall benefit of vortioxetine during the computerized cognitive training period. The primary goal of the present study was to examine whether computerized cognitive training plus vortioxetine could alter the association of aging with changes in resting-state brain networks. Combining consistent, prolonged cognitive training with a pro-cognitive and pro-neuroplastic medication presents an exciting opportunity to intervene and attenuate or reverse effects of aging on brain function and cognition.

We expected that computerized cognitive training plus vortioxetine would mitigate age-related changes in whole-brain resting-state networks, compared to computerized cognitive training plus a placebo. Specifically, we hypothesized that vortioxetine with daily cognitive training would increase mean whole-brain network strength and mean network segregation from before to after the intervention period. To contextualize our primary aim, we first tested our expectation to replicate past literature reporting that within-network strength and network segregation are negatively correlated with age. We additionally hypothesized that mean within-network strength and network segregation would positively predict cognition at baseline before the intervention began. Exploratory analyses (reported in Supplemental Materials) examined the relation between cognition and the baseline strength of 8 individual cortical and subcortical networks known for their role in cognitive processes (controlling for age), as context for appreciating the subsequent impact of the intervention. Lastly, we explored the impact of the intervention on the relationship between aging and pre-to-post training brain change in these 8 individual networks.

METHODS

The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Protection Office of Washington University in St Louis and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Community-dwelling older adults recruited from the greater St Louis area. Details of recruitment and trial monitoring were reported previously6. Briefly, all participants were at least age 65 and self-reported age-related cognitive dysfunction. Inclusion criteria included an NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery Fluid Cognition Composite27 score within one standard deviation (SD) of the age-adjusted mean score at both the pre-baseline and baseline visits (see Measures). The upper limit of +1 SD was instituted to minimize possibility of ceiling effects of the intervention, and the lower limit of −1 SD was instituted to exclude individuals with suspected mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Additional inclusion criteria were absence of psychiatric illness including current major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder (as assessed by Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-528, Patient Health Questionnaire-929, and Penn State Worry Questionnaire-Abbreviated30). Exclusion criteria included self-report or medical records indicating dementia or other significant neurodegenerative illness, or current cognitive training. Before beginning the trial all participants were evaluated with routine safety laboratory tests, physical examination, and collection of medical history. Other psychiatric, medical, and medication exclusion criteria reported in6.

Many participants in the clinical trial declined or were ineligible for MRI scanning. Accordingly, the present study represents a subset of the participants who enrolled in the full clinical trial6. We describe here the results obtained in the MRI protocol. Analyses include all valid fMRI data passing quality assurance (procedures described in Supplemental Materials), irrespective of whether participants completed the entire 6-month protocol. Sixty-nine participants completed a baseline fMRI scan, of which 66 passed quality assurance validation and are included in baseline cross-sectional analyses of the relationship between age and resting state networks (age M(SD)=71.23(4.86), range 65-85 years; 34 women, 32 men. Ten identified as Black/African American (15.2%), 52 as White (78.8%), 1 as Asian (1.5%), and 3 identified as multi-racial (4.5%). Two participants also identified as Hispanic.

Between the MRI study visit and baseline cognitive testing visit six individuals dropped out or were no longer eligible (3 women, 3 men). Thus, 60 participants who completed the baseline MRI scan and cognitive testing are included in cross-sectional analyses of the relations between cognition and resting state networks. Participants were randomly assigned to receive vortioxetine (10mg fixed dosage) or a visually identical placebo pill (double-blinded randomization described in6). For administrative reasons, only participants who completed the intervention after a certain date were eligible for invitation for a post-intervention MRI scan. All 20 who completed the intervention after that date granted their consent to complete the post-intervention MRI scan, passed MRI data quality assurance, and were included in longitudinal analyses (age M(SD)=70.7(4.19), range 65-79 years; 11 women, 9 men; vortioxetine n=10, placebo n=10).

Measures

The outcome measure of cognition was operationalized as the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery Fluid Cognition Composite score27. NIH Toolbox was evaluated upon study enrollment (pre-baseline), at randomization to intervention group (baseline), and the 4-week, 12-week, and 26-week (6-month) post-randomization study visits. The present study analyses evaluate raw NIH Toolbox fluid cognition scores (not age-adjusted) from the baseline and 6-month study visits (i.e., post-intervention). To assure participants did not have clinically significant cognitive impairment, they also completed the Mini Mental State Exam31 immediately prior to the baseline MRI scan (M(SD)=28.95(1.22), range 26-30 for sample included in baseline analyses, N=66). Other assessments collected were previously reported6, and will not be discussed further here.

Study Design and Procedures

Participants who were eligible and willing completed the MRI protocol upon study enrollment and at the 6-month visit. Participants in both the vortioxetine and placebo groups were assigned to complete 6 months of intensive (5 times per week for 30 minutes/day), adaptive (30 levels of difficulty) computerized training using “Scientific Brain Training Pro” (www.scientificbraintrainingpro.com)32,33. A broad variety of fluid cognition domains typically evidencing age-related cognitive decline were trained: executive function, visuospatial memory, memory retrieval, information processing speed, visual attention, and working memory. For full description of the cognitive training protocol, participant monitoring, and compliance see6.

MRI Acquisition and Processing

MRI data were acquired from a Siemens Prisma 3.0T scanner with a 20-channel Head Matrix Coil (Erlangen, Germany). Acquisition parameters were modeled off the multiband EPI sequences available through the Center for Magnetic Resonance Research (CMRR; http://www.cmrr.umn.edu/multiband). The scan protocol included a T1-weighted high-resolution (MP-RAGE) structural image, T2-weighted turbo spin echo structural image, and two spin echo planar images collected in opposite phase encoding directions (A-P/P-A). Up to 4 BOLD resting state fMRI (rs-fMRI) runs of 7 min. each were collected using a multiband EPI sequence. Participants were instructed to focus on a crosshair (+) at the center of the screen and let their mind wander. Due to limitations of time or discomfort a few participants had fewer than 4 rs-fMRI runs collected at baseline (Baseline <4 runs: 14/66 [21%]; Follow-up <4 runs: 1/20 [5%]). Functional data were subject to standard image preprocessing34,35. (Full specifications of scanner protocol, MRI preprocessing, and quality assurance criteria are provided in Supplemental Materials.) After preprocessing and frame censoring36,37, at baseline participants had Median=24.64min low-motion resting state data and at follow-up Median=25.12min.

Network Analyses

We extracted the resting state time series from 300 functionally-defined 10mm radius spherical regions of interest (ROIs; https://greenelab.wustl.edu)16,18. Pearson correlations were computed on the preprocessed and frame-censored time courses of the signal from each ROI to every other ROI. Thus, a 300x300 correlation matrix representing the community structure of all ROIs was created for each individual for each MRI visit. Matrices were Fisher z-transformed, with positive and negative values retained19,20,38.

The average within-network connectivity strength for each network for every individual at each visit was computed by averaging correlation values across the ROI-ROI pairwise within a given network. Whole brain within-network strength was computed as the mean across 16 networks. Whole brain network segregation was computed as the mean of within-network connectivity across all networks minus the mean of all between-networks connectivity, as a proportion of mean within-network connectivity across all networks19,20,38; Network Segregation=[z(r)Within − z(r)Between] / z(r)Within. Within-person pre- to post-intervention change in within-network strength was computed as post- minus pre-intervention mean whole brain within-network strength. Within-person pre-to post-intervention change in network segregation was calculated as the individual’s post- minus pre-intervention mean whole brain network segregation.

Data Analysis Plan

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Baseline Brain Networks and Cognition

First we assessed whether the current sample would replicate prior reports of decreasing network integrity with aging (N=66)19,23,39. We correlated age with mean whole-brain within-network strength and with network segregation at baseline. Next, we tested whether baseline brain networks would predict the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery Fluid Cognition Composite raw score (n=60) using two multiple linear regressions. The first model tested whether baseline mean whole-brain within-network strength would predict the Toolbox score, including age as a covariate. The second model tested whether baseline mean network segregation would predict the Toolbox score, with age as a covariate.

Longitudinal Analyses of Effects of Intervention

To identify whether vortioxetine significantly influenced the age-related reductions in network properties over the intervention period, we conducted two multiple linear regression analyses. First, we tested whether the medication intervention would significantly interact with age to predict degree of pre-to-post change in mean within-network strength, i.e., whether relationship would differ for the vortioxetine vs placebo group (n=20). Follow-up simple slopes tests clarified significant interactive effects of age and vortioxetine. A parallel regression analysis tested whether vortioxetine would significantly interact with age to predict degree of pre-to-post change in network segregation.

All correlation hypotheses were tested using two-tailed Pearson’s correlations. All regressions fitted a linear model (estimated using Ordinary Least Squares), and p-values were computed using the Wald approximation. All independent samples t-tests used Student’s two-tailed tests. Levene’s tests demonstrated no significant differences in variance between groups compared in t-tests (all ps>.05). Data analysis plan for exploratory approaches is reported in Supplemental Materials.)

RESULTS

Cross-sectional relationship of brain networks with age and cognition

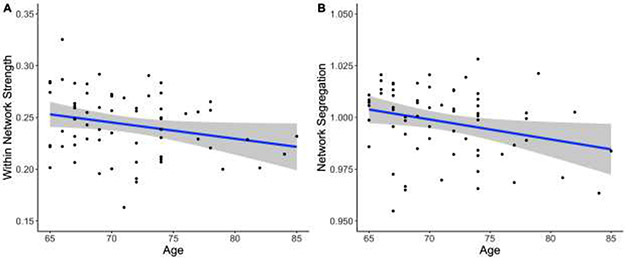

There was a significant negative correlation between age and baseline mean within-network strength (r(64)= −.24, p= .048, 95% CI [−0.46 – −0.002]). As age increases, mean within-network strength decreases. There was also a significant negative correlation between age and baseline network segregation (r(64)= −.27, p=.026, [−0.48 – −0.03]). As age increases network segregation decreases (Figure 1). (ROI connectivity matrix shown in Supplementary Figure S1-A.)

Figure 1. Aging is negatively correlated with mean within-network strength and network segregation.

Mean within-network resting state functional connectivity, r(64)= −.24, p=.048 (A), and mean network segregation decrease with age, r(64)= −.27, p=.026 (B), in cognitively normal older adult participants (N=66). Grey shaded areas indicate a 95% confidence interval.

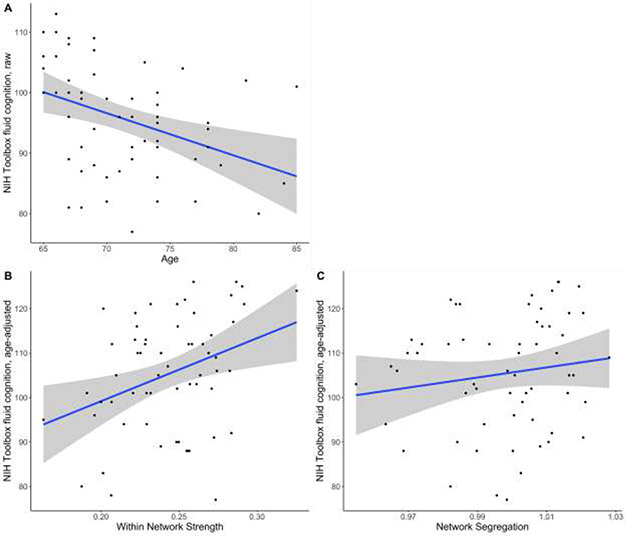

To assess effects of whole-brain network integrity on cognition cross-sectionally, we fitted a linear model to predict baseline Toolbox fluid cognition score with mean within-network strength and age. The model explains a significant proportion of variance of the cognitive scores (R2= .25, F(2, 57)= 9.50, p=.0003, adj. R2= .22). Most importantly, mean within-network integrity significantly positively predicts Toolbox fluid cognition score, after correcting for age (B=88.90, t(57)=2.67, p=.01, Std. β=0.31, Std. 95% CI [0.08 – 0.55]; Figure 2B). We also fitted a linear model to predict Toolbox fluid cognition score with network segregation and age. The model explains a significant proportion of variance (R2= .16, F(2, 57)= 5.47, p= .007, adj. R2= .13). Notably, network segregation does not significantly predict baseline Toolbox fluid cognition score (B=36.41, t(57)=0.56, p=.58, Std. β=0.07, Std. 95% CI [−0.18 – 0.32]; Figure 2C). In both models age significantly negatively predicts Toolbox fluid cognition score (Within-network model: B= −0.57, t(57)=2.72, p=.009, Std. β= −0.32, Std. 95% CI [−0.56 – −0.09]. Network segregation model: B= −0.66, t(57)=2.99, p=.004, Std. β= −0.38, Std. 95% CI [−0.63 – −0.12]; See Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Relationships of cognition to aging, within-network strength, and network segregation.

Increasing age predicted lower Toolbox fluid cognition scores in cognitively normal older adults, B= −0.70, t(58)= −3.28, p= .002. (A). Greater mean whole brain within-network strength predicted higher fluid cognition scores (age-adjusted), B= 141.76, t(58)= 2.81, p= .007 (B) but network segregation did not predict fluid cognition scores (age-adjusted), B=113.21, t(58)= 1.17, p= .25 (C). n=60. Grey shaded areas indicate a 95% confidence interval.

Longitudinal Analyses of Effects of Intervention

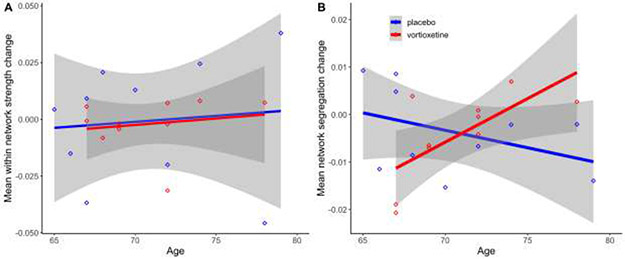

To test the primary study aim, we fitted a linear model to test whether age and intervention group would independently or interactively predict pre-to-post intervention change in whole brain mean within-network strength. The model does not explain a significant proportion of variance (R2= .01, F(3, 16)=0.07, p=.98, adj. R2= −.17). There were no significant main or interactive effects of age and intervention group predicting change in within-network strength (All Bs < ∣0.005∣, all t(16)s < 0.36, all ps>.72, all Std. βs < ∣0.11∣. Full results reported in Table 1). Results depicted in Figure 3A. (Follow-up and pre-to-post change ROI connectivity matrices shown in Supplementary Figure S1-B & S1-C.)

Table 1.

Regression effects of age and intervention group (cognitive training with placebo versus cognitive training plus vortioxetine) to predict change in mean resting state network strength (A) and network segregation (B) over the 6-month trial

| A. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-network strength change | ||||||

| Predictors | Estimate | Std. Error | t-value | Beta | Std. 95% CI | p |

| Intercept | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.36 | 0.03 | −0.69 – 0.76 | 0.722 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.11 | −0.53 – 0.75 | 0.727 |

| Intervention | −0.00 | 0.18 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −1.09 – 0.96 | 0.982 |

| Age * Intervention | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −1.11 – 1.13 | 0.987 |

| Observations | 20 | |||||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.013 / −0.172 | |||||

| B. | ||||||

| Network Segregation change | ||||||

| Predictors | Estimate | Std. Error | t-value | Beta | Std. 95% CI | p |

| Intercept | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.28 | 0.02 | −0.58 – 0.62 | 0.219 |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.00 | −1.38 | −0.35 | −0.88 – 0.19 | 0.186 |

| Intervention | −0.18 | 0.07 | −2.77 | −0.08 | −0.93 – 0.77 | 0.014 |

| Age * Intervention | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.76 | 1.21 | 0.28 – 2.14 | 0.014 |

| Observations | 20 | |||||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.326 / 0.199 | |||||

Notes: Estimate represents unstandardized regression weights. Beta indicates the standardized regression weights. Std. 95% CI is the standardized 95% confidence interval. t-value df = 16. Significant effects are indicated in bold font.

Figure 3. Age interacted with intervention group to predict network segregation change but not within-network strength change.

Main and interaction effects of age and intervention group did not predict within-network change (All Bs < ∣.005∣, all ts<.36, all ps> .72 (Full results reported in Table 1.) (A). Significant interaction effects of age and intervention group predicted change in network segregation, B= 0.0026, t(16)= 2.76, p= .014. Age positively predicted network segregation change only in the vortioxetine group, B= 0.0018, t(16)= 2.41, p= .029 (B). Positive change values indicate increase over time from baseline MRI to 6-month follow-up MRI. n=20. Grey shaded areas indicate a 95% confidence interval.

We fitted a linear model to test whether age and intervention group would independently or interactively predict pre-to-post intervention change in network segregation. The model R-squared value is .33, but does not explain a significant proportion of variance (F(3, 16)=2.58, p=.09, adj. R2= .20). Intervention group significantly negatively predicts network segregation change (B= −0.18, t(16)=2.77, p=.014, Std. β= −0.08, Std. 95% CI [−0.93 – 0.77]), but age did not significantly predict network segregation change independently (B= −0.0007, t(16)=1.38, p=.19, Std. β= −0.35, Std. 95% CI [−0.88 – 0.19]). The main effect of intervention group is qualified by interaction between age and intervention group, which significantly positively predicts network segregation change (B=0.0026, t(16)=2.76, p=.014, Std. β=1.21, Std. 95% CI [0.28 – 2.14]). Full results reported in Table 1 and depicted in Figure 3B. Post hoc simple slopes tests regressed age on change in network segregation independently for each intervention group to follow-up the significant interaction of age and intervention group in predicting network segregation. As shown in Figure 3B, age significantly positively predicts change in network segregation in the training+vortioxetine group (B= 0.0018, t(16)=2.41, p=.029), but not in the training+placebo group (B= −0.0007, t(16)= 1.38, p=.19). Exploratory analyses reported in Supplemental materials.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the effects of augmenting 6 months of computerized cognitive training with the novel multimodal antidepressant medication vortioxetine (versus placebo) on changes in resting state brain network integrity from pre- to post-intervention in a sample of older adults with age-related cognitive decline. The key findings were that age had an interactive effect with intervention group (training+vortioxetine vs training+placebo) on the degree of change in whole brain mean network segregation, but not change in mean within-network strength, over 6 months of computerized cognitive training. Additionally, exploratory analyses identified significant effects of cognitive training with vortioxetine particularly on the relationship between age and change in cingulo-opercular strength, which is a network we also identified had a significant positive relationship with cognition at baseline.

These findings are important because network segregation and within-network strength are reduced in old age. Declines in these network measures may reflect a final common pathway for aging-related brain pathologies that impair cognitive function 40. This preliminary study indicates that the combination of cognitive training and vortioxetine produces distinct intervention-related changes in resting state brain networks. Although the results await replication in a larger sample, these outcomes indicate a promising opportunity for forestalling age-related reductions in the integrity of functional brain networks.

We first replicated literature that the integrity and segregation of brain networks decreases with aging19,24, showing effects even within the restricted age range of an older adults sample. Cross-sectional results at baseline also revealed that greater whole brain mean within-network strength predicts greater cognitive performance, even after accounting for age. These results support our hypotheses and coalesce with a substantial literature reporting that within-network integrity supports cognitive functioning22,23,39,41. However, whole brain mean network segregation did not predict baseline cognitive performance in our sample. Mean within-network strength correlated positively with cognition, although the relationship between mean resting state network segregation and cognition was not significant. Thus, our hypotheses that mean within-network strength and network segregation would positively predict cognition were partially supported.

The primary study aim identified that intervention group differentially impacted the relationship between age and whole brain network segregation. There was a significant positive effect of age on change in network segregation only for the vortioxetine group, but not the placebo group. These preliminary results suggest that vortioxetine combined with cognitive training may have a protective effect on age-associated loss of network segregation. However, notably, vortioxetine did not significantly impact the relationship between age and pre-to-post intervention change in mean within-network strength. Thus, our hypotheses that computerized cognitive training plus vortioxetine would produce longitudinal changes in brain networks were partially supported. The beneficial effects of computerized cognitive training plus vortioxetine are most evident in changes in the degree to which networks can function discretely and effectively engage and disengage, i.e., the nodes within a network are strongly synchronously engaged, while other networks are disengaged. It has been well demonstrated that decreases in network segregation are prominent in typical aging and to a more severe extent in Alzheimer’s disease19,21,42.

Although the longitudinal fMRI sample size was modest, we collected a substantial amount of resting state data per person at each timepoint (median = 22-24min.), increasing reliability of these preliminary outcomes43. Moreover, additional analyses increased confidence that results were not spurious effects in the resting state signal attributable to differences in movement or other potentially confounding distinctions between the intervention groups (e.g., age, amount of resting state data; Supplemental Materials and Table S1).

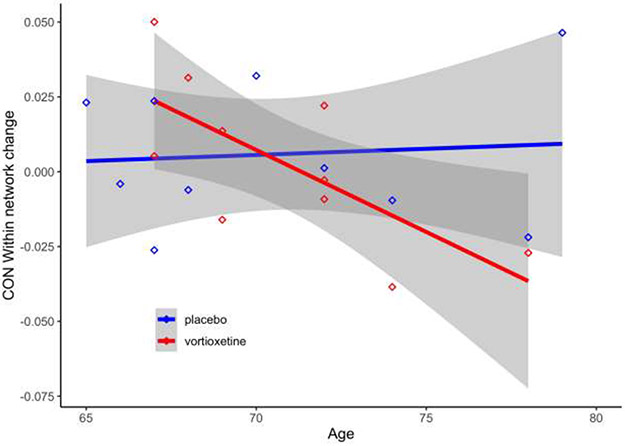

In exploratory analyses, baseline within-network strength in the default mode, cingulo-opercular, salience, and parietal memory networks predicted higher cognition (Supplemental Table S2). These results suggest networks that might be effective targets of interventions to improve older adult cognition. Intriguingly, the increase in cingulo-opercular within-network strength across the intervention period also significantly differed between the intervention groups (Figure 4, Supplemental Table S3). Cingulo-opercular network strength significantly increased for the younger versus the older half of the active treatment group (but not placebo group). These results are promising in light of baseline analyses identifying a positive relationship between cingulo-opercular network and cognition, and agree with prior literature41. The known neuroplastic mechanisms of action of vortioxetine11-13 may significantly affect regions within the cingulo-opercular network26 (e.g., ventral and subgenual anterior cingulate, medial inferior and superior frontal gyri, and insula). Younger-old adults may benefit most from the pro-neuroplastic effects of vortioxetine in combination with cognitive training.

Figure 4. Age interacts with intervention group to predict cingulo-opercular network change.

Significant interactive effects of age and intervention group predict change in cingulo-opercular (CO) network strength (B= −0.0059, t(16) = 2.18, p= .045). Age negatively predicted change in network strength only in the vortioxetine group (B= −0.0055, t(16)= 2.47, p= .025). Change in within-network strength significantly decreased with age such that network strength increased for the younger versus the older portion of the vortioxetine group. (Full results reported in Supplemental Table 2S.) n=20. Grey shaded areas indicate a 95% confidence interval.

Limitations and Future Directions

This preliminary study was part of a larger randomized clinical trial designed to test the combined effect of cognitive training plus vortioxetine (vs placebo), and, as such, did not include comparison groups who were not receiving the daily cognitive training. Monitoring over a longer horizon after completing the intervention also would be informative about the retention of the cognitive improvements and network connectivity demonstrated immediately following 6 months of training. An additional MRI scan at a midway point (e.g., at 3 months) could offer insights into the trajectory of change in resting state networks and correspondence to the time point at which the active intervention group had significantly greater NIH Toolbox fluid cognition scores. In future studies additional outcome measures evaluating cognitive changes pre- to post-training could more comprehensively assess transfer to other abilities. Replication in a larger sample of older adults will add further credibility to the current significant neuroimaging findings. Biomarkers of Alzheimer pathology may increase the explanatory power of the models.

Conclusions

Vortioxetine added to computerized cognitive training produced significantly greater changes in older adult brain network organization than cognitive training alone across a 6-month trial. Discrete intervention group effects were most evident in the interactions of aging with longitudinal changes in whole brain network segregation and with cingulo-opercular network strength. These neural effects were coupled with significant increases in fluid cognition in both groups across the trial period. This preliminary study indicates that for older adults experiencing age-related cognitive decline, adding a pro-cognitive medication to intensive cognitive training may have additive or synergistic beneficial effects. Moreover, as only the third study to investigate the effects of a course of vortioxetine on human functional brain activity, and the first in older adults, this study also advances knowledge of the neural mechanisms underlying vortioxetine’s pro-cognitive and pro-neuroplastic effects.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

1 The primary question addressed was whether adding a pro-cognitive medication (vortioxetine) to cognitive training would alter the association of aging with changes in resting state brain networks across a 6-month trial period.

2 Vortioxetine added to computerized cognitive training produced significantly greater changes in older adult brain network organization than cognitive training alone over 6 months. Discrete intervention group effects were most evident in the interactions of aging with longitudinal changes in whole brain network segregation and with cingulo-opercular network strength.

3 For older adults experiencing age-related cognitive decline, adding vortioxetine to intensive cognitive training has a potentially beneficial effect on the correspondence between aging and functional brain network organization.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AG049075 (JW), UL1TR002345 (EL), and HD103525 (JS & AZS); Takeda Pharmaceuticals (EL); and Saint Louis University (JW). Additional funding is from the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research and the Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders (EL). Saint Louis University and Washington University School of Medicine provided facilities and administrative assistance.

We thank members of The Healthy Mind Lab, especially Jissell Torres, Roz Abdulqader, and Julie Schweiger, for assistance with participant recruitment, assessments, and monitoring; Karin Meeker, Elizabeth Erickson, Hannah Wilks, Manon Masson, and Linda Hood for assistance with MRI data collection; and Benjamin Seitzman, Tomoyuki Nishino, and Babatunde Adeymo for assistance and advice on neuroimaging methods and network analyses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03272711

Disclosures & Conflicts of Interest

Jill D. Waring, PhD none declared

Samantha E. Williams, PhD none declared

Angela Stevens, BS none declared

Anja Pogarcic, MS none declared

Joshua S. Shimony, MD, PhD none declared

Abraham Z. Snyder, MD, PhD is a consultant for Sora Neuroscience, LLC.

Christopher R. Bowie, PhD has received grant support from Lundbeck, Pfizer, and Takeda and in-kind research support from Scientific Brain Training; he has served as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, and Pfizer; and he receives royalties from Oxford University Press.

Eric J. Lenze, MD has received grant support (non-federal) from COVID Early Treatment Fund, Mercatus Center Emergent Ventures, the Skoll Foundation, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Janssen, and MagStim (support in kind); he has received consulting fees from Merck, IngenioRx, Boeringer-Ingelheim, Prodeo, Pritikin ICR; and has applied for a patent for the use of fluvoxamine in the treatment of COVID-19.

Previous Presentation

Some results reported were previously presented in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, Chicago, IL (Oct 19-23, 2019).

References

- 1.Park DC, Lautenschlager G, Hedden T, Davidson NS, Smith AD, Smith PK. Models of visuospatial and verbal memory across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17(2):299–320. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.2.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Yu L, et al. Much of late life cognitive decline is not due to common neurodegenerative pathologies. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(3):478–489. doi: 10.1002/ana.23964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern Y, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Bartrés-Faz D, et al. Whitepaper: Defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2020; 16(9): 1305–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lustig C, Shah P, Seidler R, Reuter-Lorenz PA. Aging, Training, and the Brain: A Review and Future Directions. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19(4):504–522. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9119-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lampit A, Hallock H, Valenzuela M. Computerized cognitive training in cognitively healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of effect modifiers. PLoS Med. 2014;11(11):e1001756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenze EJ, Stevens A, Waring JD, et al. Augmenting computerized cognitive training with vortioxetine for age-related cognitive decline: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(6):548–555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19050561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Diego-Adeliño J, Crespo JM, Mora F, et al. Vortioxetine in major depressive disorder: from mechanisms of action to clinical studies. An updated review. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2022;21(5):673–690. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2022.2019705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(4):215–223. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3283542457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahableshwarkar AR, Zajecka J, Jacobson W, Chen Y, Keefe RSE. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Active-Reference, Double-Blind, Flexible-Dose Study of the Efficacy of Vortioxetine on Cognitive Function in Major Depressive Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(8):2025–2037. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIntyre RS, Florea I, Tonnoir B, Loft H, Lam RW, Christensen MC. Efficacy of Vortioxetine on Cognitive Functioning in Working Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(01):115–121. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m10744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dale E, Zhang H, Leiser SC, et al. Vortioxetine disinhibits pyramidal cell function and enhances synaptic plasticity in the rat hippocampus. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(10):891–902. doi: 10.1177/0269881114543719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez C, Asin KE, Artigas F. Vortioxetine, a novel antidepressant with multimodal activity: Review of preclinical and clinical data. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2015;145:43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen F, du Jardin KG, Waller JA, Sanchez C, Nyengaard JR, Wegener G. Vortioxetine promotes early changes in dendritic morphology compared to fluoxetine in rat hippocampus. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;26(2):234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreira LK, Busatto GF. Resting-state functional connectivity in normal brain aging. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37(3):384–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(27):9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hacker CD, Laumann TO, Szrama NP, et al. Resting State Network Estimation in Individual Subjects. Neuroimage. 2013;82:616–633. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, et al. Functional Network Organization of the Human Brain. Neuron. 2011;72(4):665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seitzman BA, Gratton C, Marek S, et al. A set of functionally-defined brain regions with improved representation of the subcortex and cerebellum. NeuroImage. 2020;206:116290. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan MY, Park DC, Savalia NK, Petersen SE, Wig GS. Decreased segregation of brain systems across the healthy adult lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(46). doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415122111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen JR, D’Esposito M. The Segregation and Integration of Distinct Brain Networks and Their Relationship to Cognition. Journal of Neuroscience. 2016;36(48):12083–12094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2965-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ewers M, Luan Y, Frontzkowski L, et al. Segregation of functional networks is associated with cognitive resilience in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2021;144(7):2176–2185. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brier MR, Thomas JB, Snyder AZ, et al. Loss of Intranetwork and Internetwork Resting State Functional Connections with Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(26):8890–8899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5698-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damoiseaux JS. Effects of aging on functional and structural brain connectivity. Neuroimage. 2017;160:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.01.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spreng RN, Stevens WD, Viviano JD, Schacter DL. Attenuated anticorrelation between the default and dorsal attention networks with aging: evidence from task and rest. Neurobiology of Aging. 2016;45:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith J, Browning M, Conen S, et al. Vortioxetine reduces BOLD signal during performance of the N-back working memory task: a randomised neuroimaging trial in remitted depressed patients and healthy controls. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(5):1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong S, Li W, Zhou Y, et al. Vortioxetine Modulates the Regional Signal in First-Episode Drug-Free Major Depressive Disorder at Rest. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022;13:950885. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.950885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heaton RK, Akshoomoff N, Tulsky D, et al. Reliability and validity of composite scores from the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery in adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20(6):588–598. doi: 10.1017/S1355617714000241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.First M, Williams J, Karg R, Spitzer R. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5. American Psychiatric Assocation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crittendon J, Hopko DR. Assessing worry in older and younger adults: Psychometric properties of an abbreviated Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ-A). Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20(8):1036–1054. doi: 10.1016/J.JANXDIS.2005.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowie CR, McGurk SR, Mausbach B, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Combined Cognitive Remediation and Functional Skills Training for Schizophrenia: Effects on Cognition, Functional Competence, and Real-World Behavior. AJP. 2012;169(7):710–718. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11091337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowie CR, Gupta M, Holshausen K, Jokic R, Best M, Milev R. Cognitive remediation for treatment-resistant depression: effects on cognition and functioning and the role of online homework. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(8):680–685. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31829c5030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raut RV, Mitra A, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME. On time delay estimation and sampling error in resting-state fMRI. Neuroimage. 2019;194:211–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder AZ, Nishino T, Shimony JS, et al. Covariance and Correlation Analysis of Resting State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Data Acquired in a Clinical Trial of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Exercise in Older Individuals. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:825547. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.825547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2142–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Power JD, Mitra A, Laumann TO, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Methods to detect, characterize, and remove motion artifact in resting state fMRI. Neuroimage. 2014;84:320–341. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meeker KL, Ances BM, Gordon BA, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 moderates the relationship between brain functional network dynamics and cognitive intraindividual variability. Neurobiology of Aging. 2021;98:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sala-Llonch R, Junqué C, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, et al. Changes in whole-brain functional networks and memory performance in aging. Neurobiology of Aging. 2014;35(10):2193–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas JB, Brier MR, Snyder AZ, Vaida FF, Ances BM. Pathways to neurodegeneration: Effects of HIV and aging on resting-state functional connectivity. Neurology. 2013;80(13): 1186–1193. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318288792b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hausman HK, O’Shea A, Kraft JN, et al. The Role of Resting-State Network Functional Connectivity in Cognitive Aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020; 12:177. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Contreras JA, Avena-Koenigsberger A, Risacher SL, et al. Resting state network modularity along the prodromal late onset Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Neuroimage: Clinical. 2019;22:101687. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Birn RM, Molloy EK, Patriat R, et al. The effect of scan length on the reliability of resting-state fMRI connectivity estimates. Neuroimage. 2013;83:550–558. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.