Abstract

Background.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is characterized by Th2-dominated skin inflammation and systemic response to cutaneously encountered antigens. The Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 play a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD. The Q576->R576 polymorphism in the IL-4Rα chain common to IL-4 and IL-13 receptors alters IL-4 signaling and is associated with asthma severity.

Objective:

To investigate whether the IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism is associated with AD severity and exaggerates allergic skin inflammation in mice.

Methods.

Nighttime itching interfering with sleep, Rajka-Langeland and Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores were used to assess AD severity. Allergic skin inflammation following epicutaneous (EC) sensitization of mice one or two IL-4RαR576 alleles (QR and RR) and IL-4RαQ576 (QQ) controls was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of cells and qRT-PCR analysis of cytokines in skin.

Results.

The frequency of nighttime itching in 190 asthmatic inner-city children with AD, as well as Rajka-Langeland and EASI scores in 1116 Caucasian AD patients enrolled in the Atopic Dermatitis Research Network, were higher in subjects with the IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism compared to those without, with statistical significance for the Rajka-Langeland score.

Following EC sensitization of mice with ovalbumin or house dust mite, skin infiltration by CD4+ cells and eosinophils, cutaneous expression of Il4 and Il13, transepidermal water loss, antigen-specific IgE antibody levels, and IL-13 secretion by antigen-stimulated splenocytes were significantly higher in RR and QR mice compared to QQ controls. Bone marrow radiation chimeras demonstrated that both hematopoietic cells and stromal cells contribute to the mutants’ exaggerated allergic skin inflammation.

Conclusion.

The IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism predisposes to more severe AD and increases allergic skin inflammation in mice.

Keywords: atopic dermatitis, IL4Rα R576 polymorphism, allergic skin inflammation

Capsule Summary.

Identification of the IL-4Rα R576 variant as a genetic biomarker for AD severity demonstrates that immune response genes are important determinants of disease severity in AD.

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects ~17 % of children and is associated with food allergy and development of asthma1–3. AD patients have a defective skin barrier that causes dry itchy skin and allows cutaneous introduction of antigens. In many AD patients there is a heterozygous mutation in the epidermal gene Filaggrin (FLG) that impairs skin barrier function4, 5. The disease is characterized by Th2-dominated skin inflammation, with increased cutaneous expression of IL-4 and IL-13 and dermal infiltration by CD4+ Th2 cells and eosinophils, and by a systemic immune Th2 response, with high serum IgE, IgE antibodies to allergens, eosinophilia and elevated blood Th2 biomarkers1–3.

The Th2 response is essential for the development of AD as illustrated by studies in patients with primary immunodeficiency and mouse models of AD6, 7. Thus, AD involves an epidermal component of skin barrier dysfunction, and a Th2 immune response elicited by cutaneous sensitization through the disrupted skin barrier1–3. These two components are interrelated. A defective skin barrier causes a dry itchy skin and allows cutaneous introduction of antigens. Th2 cytokines in the skin alter gene expression by keratinocytes downregulating filaggrin and further disrupting skin barrier integrity.

The receptors for the Th2 cytokines IL-4 (IL-4R) and IL-13 (IL-13R) share the signal transducing chain IL-4Rα. The critical roles of IL-4 and IL-13 in AD are demonstrated by the beneficial effect of IL-4Rα blockade in a substantial percentage of AD patients8. A wide variety of cells express both IL-4R and IL-13R. IL-4 drives the generation of Th2 cells from naïve T cells that recognize antigen. IL-4 and IL-13 drive keratinocytes to produce chemokines that attract CD4+Th2 cells and eosinophils to the skin. Multiple independent genetic analyses have revealed associations between polymorphisms in IL4, IL13 and IL4RA and AD9–11. In particular, an rs1801275 A to G substitution in IL4RA that results in a glutamine- (Q) to arginine (R) substitution at position 576 of IL-4Rα (IL-4Rα Q576 -> IL-4Rα R576) has been linked to asthma exacerbation and severity12–15. The IL-4Rα R576 variant is common in minority racial populations. It has an allele frequency of ~65% in African Americans and ~40% in Latinos16, 17, two populations prone to develop severe asthma and AD18, 19. Its frequency in the Caucasian population ranges between 10% and 20%. The Q576 residue is conserved in the murine IL-4Rα chain. It lies immediately downstream of a STAT6-binding site at Tyr575, one of three such sites present in IL-4Rα. The R576 mutation has no discernable effect on STAT6 activation. However, it enables the mutant IL-4Rα to recruit the adaptor Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (GRB2), and thereby drive mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling20.

We had observed that the incidence of physician-diagnosed AD is higher in inner city asthmatic school children who carry the IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism21, 22. We herein report that the IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism is associated with increased disease severity in AD. Furthermore, we demonstrate that mice that carry the Il4raR576 mutation exhibit exaggerated allergic skin inflammation following epicutaneous (EC) sensitization of tape stripped skin with antigen, a model that shares many characteristics with human AD23–25. Identification of the IL-4Rα R576 variant as a genetic biomarker for AD severity demonstrates that immune response genes can be important determinants of disease severity in AD.

METHODS

Association analysis of R576 polymorphism and severity of night itching in children enrolled in the SICAS studies and carrying a physician diagnosis of eczema.

The School Inner-city Asthma Studies (SICAS-1 and SICAS-2) were conducted between 2008 and 2020 in children (ages 4 to 15 years) with persistent asthma attending inner-city schools in a city in the northeast United States26–29. All children from the SICAS cohorts who had genotyping for IL4R576 performed and had reported physician-diagnosed of eczema were included in this study. Genotyping of the IL4RAQ576 and IL4RAR576 alleles was performed as previously described20. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in the study. The studies received the approval by the Boston Children’s Hospital institutional review board and participating school system.

To test the association between night itching and the polymorphism, we used generalized estimating equations (binomial family, logit link, exchangeable correlation structure, and robust standard errors) clustered at the participant level and adjusted for age, gender, sex, and income. Alpha was set at 0.05 and tests were two-tailed.

Association analysis of R576 polymorphism and AD severity in Atopic Dermatitis Research Network (ADRN) cohorts.

The ADRN is a National Institute of Health sponsored multicenter study of patients with AD in the United States. Study subjects included unrelated non-Hispanic European American individuals from the ADRN registry. Patients were asked to self-identify their race and ethnicity from a list of United States Census categories. All samples used for this study were obtained following written informed consent from participants. The University of Colorado, Johns Hopkins University, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s hospital of Chicago, Oregon Health & Science University, Boston Children’s Hospital, University of California San Diego, University of Rochester Medical Center, University of Southern California, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and National Jewish Health Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this study.

All study participants underwent a detailed history, physical examination, disease severity assessment, and blood draw. Disease severity was assessed by the Rajka-Langeland (R-L) and the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scoring systems. Blood samples were sent to Quest Diagnostics Laboratory for a complete blood count with differential and to the Dermatology, Allergy and Clinical Immunology Laboratory at the Johns Hopkins Asthma and Allergy Center for total serum IgE. The total eosinophil count (cells/mm3) was calculated from the “CBC with differential” blood test. Log-transformed values for IgE, eosinophil count and EASI were used in the analysis. In order to adjust for any values less than 1 in the data set, before applying a log10 transformation, we added 1 to all EASI values. A Box-Cox transformation with a lambda of 1.5 was applied to the R-L score in order to normalize the distribution. We used linear models and additive (0, 1 or 2 copies of the R allele) dominant (0 denoting no R alleles, 1 denoting 1 or more copies of the R allele) and recessive (0 denoting 0 or 1 copy of the R allele and 1 denoting two copies of the R allele) encoding of the R allele to test for association between the polymorphism and severity score, using the R software package. The first five principal components of genetic ancestry, generated separately for each of the data sets from a linkage-disequilibrium pruned autosomal data set using smartPCA, were included as fixed effect covariates in the models. Inverse-variance meta-analysis was used to combine the association results across data sets.

Mice.

Il4raR576/R576mice (RR) and Il4raR576/Q576 (QR) mice on BALB/c background were previously described30. Control Il4raQ576/Q576 QQ) BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratory. All mice were kept in a pathogen-free environment and fed an OVA-free diet. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Children’s Hospital Boston.

EC sensitization.

Epicutaneous (EC) sensitization was performed as described23. Briefly, 6–8 weeks old mice were anesthetized, and their back skin was shaved, and tape tripped with a film dressing (Tagaderm, 3M) 6 times at day 0, 3 time at day 2 and 2 times for other days. EC sensitization consisted of applying a 1 cm2 gauze containing 200 μg of OVA or HDM or saline after each tape stripping every alternative day for 10 days and securing it with a film dressing. Analyses were done at D12.

Analysis of oral active anaphylaxis.

One week after the last sensitization, mice were challenged intragastrically with 150 mg of OVA in 350 μL of saline buffer. Temperature changes were measured every 5 minutes after OVA challenge by using the DAS-6001 Smart Probe and IPTT-300 transponders (Bio Medic Data Systems, Seaford, Del) injected subcutaneously. Sera were collected 60 minutes after challenge.

Analysis of airway inflammation.

One week after the last sensitization, mice were challenged intranasally with OVA (50μg) daily for 3 days. Lung resistance was measured with invasive Buxco (Buxco Electronics, Wilmington, NC) in response to increasing doses of methacholine administered by means of nebulization to anesthetized mice 24 hours after the last intranasal treatment. Immediately after death, BALF and lung was collected for analysis.

Skin histology.

Skin specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde embedded in paraffin and analyzed as previously described23.

Mouse skin cell preparation, and flow cytometry.

Cell isolation from the sensitized back skin was performed as previously described31. Skin or blood cells were preincubated with FcγR-specific blocking mAb (2.4G2) and washed before staining with the following mAbs: CD45 (30F11), CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), CD3 (17A2), CD4 (GK1.5) and Gr1 (RB6–8C5) from eBioscience (San Diego, Calif); CD11b (M1/70) from Biolegend (San Diego, Calif); and SiglecF (E50–2440) from BD Biosciences (San Jose, Calif). BV605 streptavidin from Biolegend was used to detect biotinylated antibodies. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry by using an LSRFortessa machine (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed with FlowJo software. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using an LSRFortessa machine (BD Biosciences). The data was analyzed with FlowJo software.

Analysis of cytokine expression in skin.

Total skin RNA extraction and measurement of cytokines were performed and analyzed as previously described32.

TEWL.

Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) was measured as previously described using a Dermalab instrument DermaLab universal serial bus module (Cortex Technology, Hadsund, Denmark)23.

Determination of antigen-specific antibodies in serum.

Detection of OVA specific IgE was performed using a homemade sandwich ELISA for OVA-IgE as described previously33. Briefly, plates were coated with rat anti-mouse IgE (Clone R35-72, BD Bioscience). After blocking with 5% gelatin (Fisher Scientific), the coated plates were then incubated with serum samples and OVA-IgE standard. Monoclonal mouse anti-OVA IgE (clone E-C1, Chondrex) was used as standard. The plates were incubated with OVA-Biotin. OVA was biotinylated with EZ-Link™ Sulfo NHS-LC-LC-Biotin kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

For other allergen -specific Immunoglobulins, plates were first coated with OVA (20 μg/ml in 0.1M sodium bicarbonate buffer). After blocking with 1% BSA (Sigma), the coated plates were then incubated with serum samples, followed by incubation with a biotinylated rat anti-mouse IgE (clone R35–118, BD Biosciences PharMingen), rat anti-mouse IgG1 (clone A85–1, BD Biosciences PharMingen), or rat anti-mouse IgG2a (clone R19–15, BD Biosciences PharMingen). Avidin-HRP and Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) Substrate Solution from eBioscience (San Diego, Calif) were used for detection. Serum levels were expressed as optical density measured at 450 nm.

Cytokine secretion by splenocytes stimulated with antigen.

Single cell suspensions of splenocytes were cultured and stimulated with OVA or HDM and their supernatants analyzed for cytokines by ELISA as previously described32.

Mouse serum mast cell protease 1 levels.

Mouse mast cell protease 1 (mMCP-1) concentrations were measured in sera collected 1 day before and 60 minutes after oral challenge by means of ELISA with a kit for mMCP-1 per the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience).

Generation of bone marrow chimeras.

8-wk-old recipient CD45.1+ WT or Il4raR576/R576mice mice were lethally irradiated (1,200 rad delivered in two doses of 600 rad each at 3-h intervals), and injected i.v. with 5 × 106 BM cells obtained from congenic CD45.2+ WT mice or Il4raR576/R576 mice34. Chimerism was assessed by measuring the percentages of donor cells in the chimeric mice blood 8 weeks after BM reconstitution34.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA analysis on Graph-pad prism. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The IL-4Rα Q576R polymorphism is associated with a tendency for more night-time itching interfering with sleep in inner-city school age asthmatic children.

In two School Inner-city Asthma Studies (SICAS) aimed at understanding school specific environmental risk factors in asthma and allergic diseases, the questionnaire administered upon enrollment included information about physician diagnosed eczema. In addition, the number of nights per week in which itching woke up the child was assessed at multiple time points over a period of one year as an index of eczema severity (range of 1 to 6 observations per child). We analyzed the data on the 429 children in the SICAS who had been genotyped for the IL-4Rα Q576R polymorphism21, 22. Of these, 190 (44%) had been diagnosed with eczema by their physician and had available data on night itching that interfered with sleep. The mean age of the 190 children with eczema was 7.9+1.9 years (range 4–14 years), 52% were males, 37% were African Americans, 38% Hispanics, 5% Caucasians, and 19% of other racial groups (Table 1). The prevalence of the R allele in this population was high at 79% with 45% carrying a single R allele and 34% carrying two R alleles, reflecting the preponderance of patients with African American and Hispanic ancestry.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 190 children in the School Inner-city Asthma Studies with physician diagnosed eczema and night itching data

| IL4RA genotype | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| QQ n=40 (21%) | QR n=85 (45%) | RR n=65 (34%) | |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 8.0 (1.7) | 7.7 (2.0) | 8.0 (1.8) |

| Male, N (%) | 23 (58) | 46 (54) | 30 (46) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |||

| White | 8 (20) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Black | 5 (12) | 34 (40) | 32 (49) |

| Hispanic | 20 (50) | 32 (38) | 21 (32) |

| Other/unknown | 7 (18) | 18 (21) | 11 (17) |

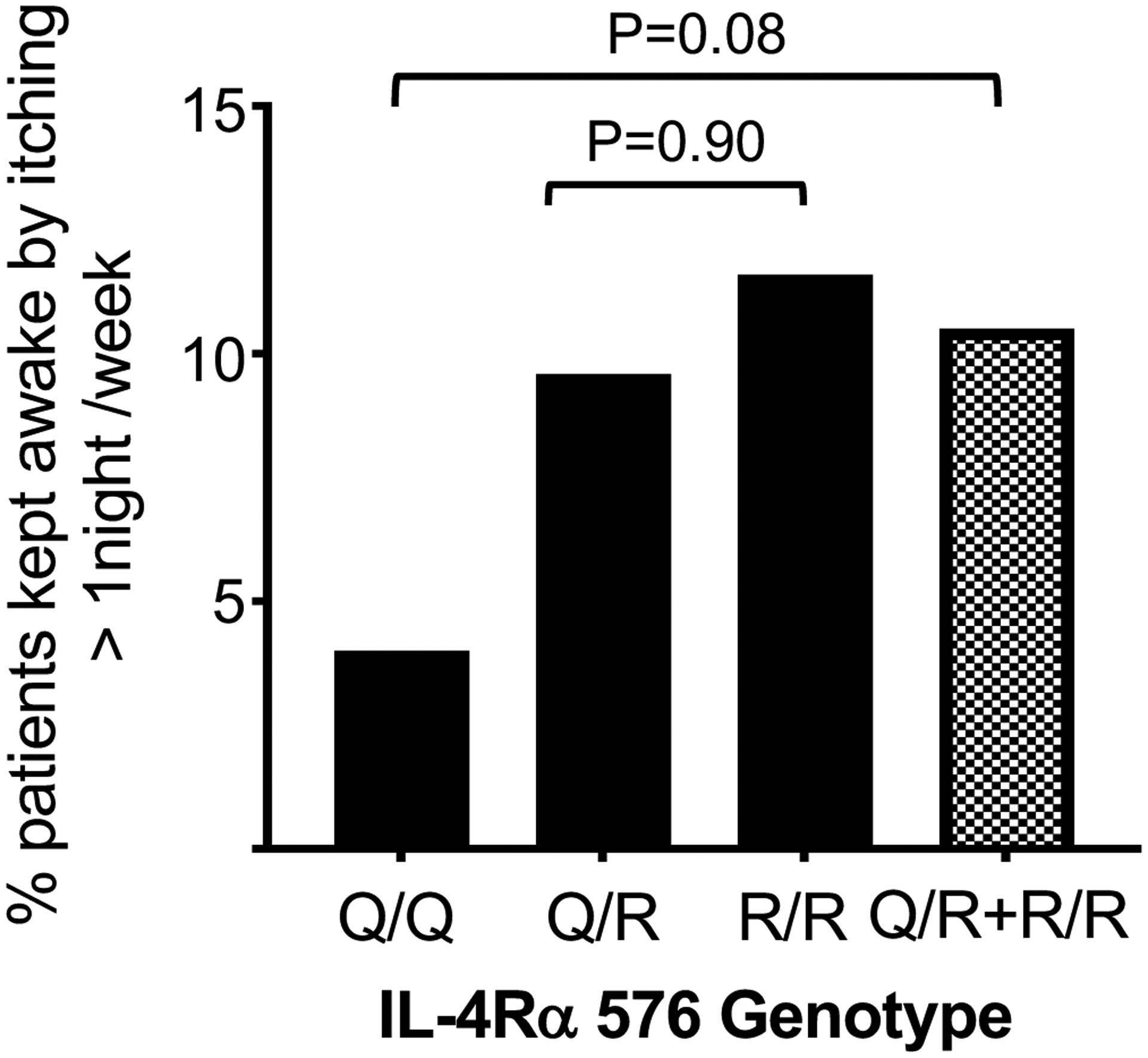

Nighttime itching that interferes with sleep is an indicator of AD severity35–37. The percentage of nighttime itching that interfered with sleep at least one night per week was higher in children carrying one or two copies of the R allele compared to children carrying two QQ alleles: 10.5% for RR and QR combined versus 4.0% for QQ (adjusted odds ratio=3.08, 95% confidence interval = 0.88–10.80, p=0.08, Fig. 1). The percentage of children with nighttime itching that interfered with sleep at least one night per week was 9.6% in the children carrying one R allele versus 11.6 % in the children carrying two R alleles (adjusted odds ratio=1.06, 95% confidence interval = 0.46–2.42, p=0.90). These results suggest that the IL-4Rα Q576R polymorphism may be associated with increased AD severity in asthmatic school age children.

Figure 1. Frequency of night itching interfering with sleep in asthmatic children with AD.

Percentage of the 189 children with AD in the SICAS studies who were kept awake by itching more than one night per week, according to their IL-4Rα genotype.

The IL-4Rα Q576R polymorphism is associated with significantly higher Rajka-Langeland disease scores in AD patients with European ancestry.

The patients with eczema in the SICAS studies were primarily African Americans and Latinos. To investigate whether the IL-4Rα Q576R polymorphism is associated with AD severity independent of racial background, we evaluated data on disease severity in a large cohort of 1116 AD patients with European ancestry on whom information was available in the Atopic Dermatitis Research Network (ADRN) repository. 692 of these patients were adults (18 years and old) and 424 were children (<18 years old). IL4RA genotype data was available on these patients through whole genome sequencing (n=540), or Illumina’s Multi-Ethnic Genotype Array (MEGA) (n=576). The IL4RA genotype frequency in this population was QQ 61%, QR 34 %, and RR 5% (Table 2A). The lower frequency of the R allele in this cohort is consistent with the patients’ European ancestry. The sex and age distribution of the patients were comparable among the three genotypes (Table 2A). There were no significant differences in serum IgE levels or blood eosinophil counts between the three groups (Table 2). Disease severity in the patients was assessed by EASI and R-L scores. Analysis of additive (0, 1 or 2 copies of the R allele), dominant (0 denoting no R alleles, 1 denoting 1 or more copies of the R allele) and recessive (0 denoting 0 or 1 copy of the R allele, 1 denoting 2 copies of the R allele) models were used to test for association between the R576 polymorphism and AD severity scores. Patients carrying one or two copies of the R allele had higher EASI and R-L scores than those carrying the QQ alleles (Table 2B). Both an additive and a dominant model, but not a recessive model, of the R allele provided a good fit to the data yielding significantly higher RL scores with p values of 0.037 and 0.02 respectively and higher EASI scores that approached significance with p values of 0.06 and 0.076 respectively (Table 2B). The differences in EASI and R-L scores between patients carrying one versus two copies of the R allele were not significant (p=0.64 and p=0.44 respectively). These results indicate that the IL-4Rα Q576R polymorphism is significantly associated with increased AD severity as assessed by R-L scores in an independent cohort of patients with European ancestry.

Table 2A.

Characteristics of the 1116 AD patients from the ADRN repository.

| IL4RA genotype | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AG/GA | GG | |

| N | 686 | 376 | 54 |

| Males (N; %) | 308 (59.6%) | 187 (36.2%) | 22 (4.3%) |

| Age; mean (SD) | 27.2 (18.4) | 26.1 (18.2) | 27.8 (19.2) |

| Total IgE* (95% CI) | 228.7 | 211.9 | 222.6 |

| (193.2–270.7) | (169.0–265.6) | (120.6–411.0) | |

| Eosinophils* (95% CI) | 219.4 | 217.9 | 254.7 |

| (204.2–235.8) | (197.5–240.5) | (192.3–337.4) | |

= Geometric Mean,

CI= Confidence Interval

Table 2B.

Meta analysis of the association between the IL4-Rα R576 polymorphism and AD severity

| AD scores | Q/Q | Q/R | R/R | Data analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=683 | n=379 | n=54 | Model | Risk | P value | |

| Mean EASI score [Min-Max] ) | 13.15 [0–66] | 13.3 [0.3–70.8] | 17.9 [1.2–56.4] | Additive | 0.066 [0.012–0.12] | 0.060 |

| Dominant | 0.067 [0.003–0.13] | 0.076 | ||||

| Recessive | 0.064 [−0.041–0.169] | 0.234 | ||||

| Mean RL score ( SD]) | 6.6 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.5) | 7.1 (1.7) | Additive | 0.748 [0.17–1.32] | 0.022 |

| Dominant | 0.798 [0.11–1.48] | 0.037 | ||||

| Recessive | 0.849 [−0.249–1.947] | 0.130 | ||||

Mice with the IL-4Rα Q576R mutation demonstrate exaggerated allergic skin inflammation in response to epicutaneous (EC) sensitization with OVA antigen.

Differences in genetic backgrounds and environmental factors confound the analysis of the effect of gene polymorphism on disease severity. We previously demonstrated that EC sensitization by application of antigen to tape stripped mouse skin elicits allergic skin inflammation that shares many features with AD skin lesions23, 24. To investigate whether the IL4RA Q576R polymorphism is associated with enhanced allergic skin inflammation independent of genetic or environmental factors, we examined the response to EC sensitization of mice that carry the IL-4Rα Q576R mutation30. To test the hypothesis that the IL4Rα Q576R polymorphism acts in a dominant manner we compared homozygous Il4raR576/R576 (RR) mice and heterozygous Il4raR576/Q576 (QR) mice to Il4raQ576/Q576 (QQ) WT controls all on Balb/C background.

As previously described23, 24, EC sensitization of wildtype QQ mice with OVA causes increased dermal infiltration by mononuclear cells, CD45+ cells, CD4+ T cells and eosinophils as well as upregulation of Il4 and Il13, but not Il17a or Ifng, expression compared to EC sensitization with saline (Fig. 2A–D). OVA sensitized skin from QR mice and RR mice exhibited increased dermal infiltration by mononuclear cells compared to QQ controls (Fig. 2B). The numbers of CD45+ cells CD4+ T cells and eosinophils in OVA sensitized skin were significantly higher in QR and RR mice compared to QQ WT controls (Fig. 2C). Moreover, RT-qPCR analysis revealed greater upregulation of Il4 and Il13, but not Il17a or Ifng, expression in OVA sensitized skin from QR and RR mice compared to QQ controls (Fig. 2D). There were no significant differences in allergic skin inflammation between mutant mice that carry one R allele (QR mice) versus two R alleles (RR mice). Cellular infiltration and cytokine expression in saline sensitized skin were comparable between all three strains examined (Fig. 2B–D).

Figure 2. Exaggerated allergic skin inflammation following EC sensitization with OVA in mice that are heterozygous or homozygous for IL-4Rα R576.

A. Experimental protocol. B-E. Representative H&E staining (B), numbers/cm2 of CD45+ cells, CD4+ T cells and eosinophils (C), mRNA levels of Il4, Il13, Il17a and Ifng (D) and TEWL (E) in saline-sensitized and OVA-sensitized skin of QQ, QR and RR mice. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments with 4–5 mice/group. Columns and bars represent mean ± SEM. * p<0.05, ** p<0.005., *** p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA.

Trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) is a measure of skin barrier integrity. TEWL is increased in AD skin lesions, and in mice at sites of allergic skin inflammation elicited by EC sensitization with OVA23, 24. TEWL at OVA sensitized skin sites was significantly higher in QR and RR mice compared to QQ controls indicating greater disruption of skin barrier integrity in mutant mice that carry the R allele (Fig. 2E). TEWL in saline sensitized skin was comparable between all three strains examined (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that the IL4R R576 polymorphism causes in a dominant manner exacerbated allergic skin inflammation in response to cutaneously introduced antigens.

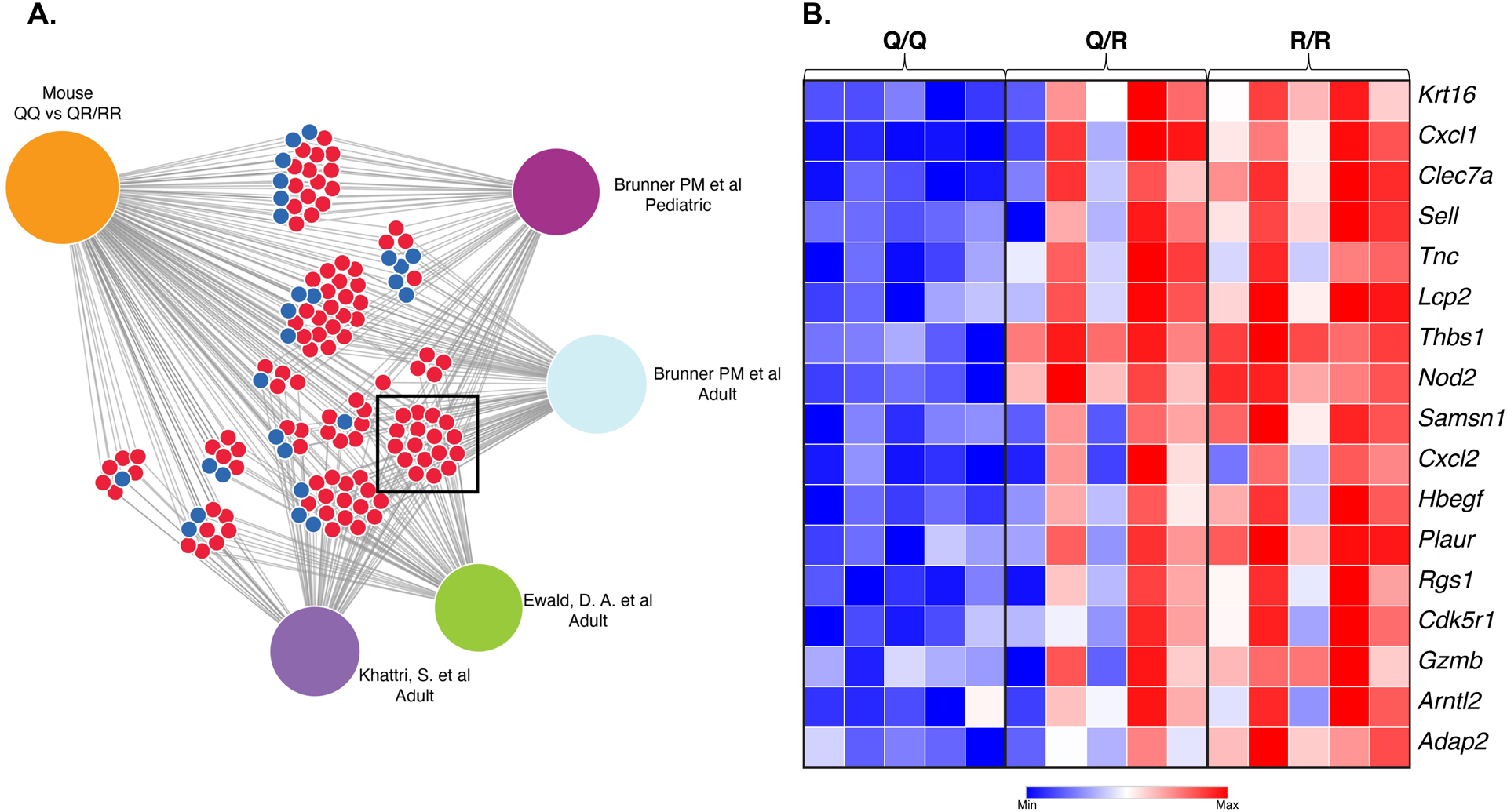

To further understand the impact of the R allele on allergic skin inflammation we compared global gene expression in OVA sensitized skin from QR and RR mice and QQ controls. OVA sensitized skin from mice carrying the R allele (QR+RR) differentially expressed 708 genes (> 2-fold change, p<0.05) compared with OVA sensitized skin from QQ controls. Of these 708 genes, 496 genes were upregulated, and 212 genes were downregulated in OVA sensitized skin from mice carrying the R allele. We performed a comparative analysis of genes differentially expressed in our dataset with four available datasets of genes differentially expressed in lesional versus non-lesional skin of AD patients38–40. We identified 136 genes differentially expressed (109 upregulated and 27 downregulated) in OVA sensitized skin of mice carrying the R allele that have been found to be similarly regulated in AD skin lesions (Fig 3A). Of these 136 genes, 17 genes, all of them upregulated, were shared between our study and all four AD patients’ datasets (Fig 3B and Table E1).

Figure 3. Gene expression in OVA sensitized skin of QQ, QR and RR mice.

A. Comparative analysis of genes differentially expressed in OVA sensitized skin of QQ vs QR+RR mice and four published data sets of genes differentially expressed in lesional versus non-lesional skin of AD patients. Blue circles represent shared downregulated genes. Red circles represent shared up-regulated genes. B. Heatmap indicating fold changes of the 17 genes shared between our study and all four AD datasets

Mice with the IL-4Rα Q576R mutation demonstrate an increased systemic Th2 response to EC sensitization with OVA antigen.

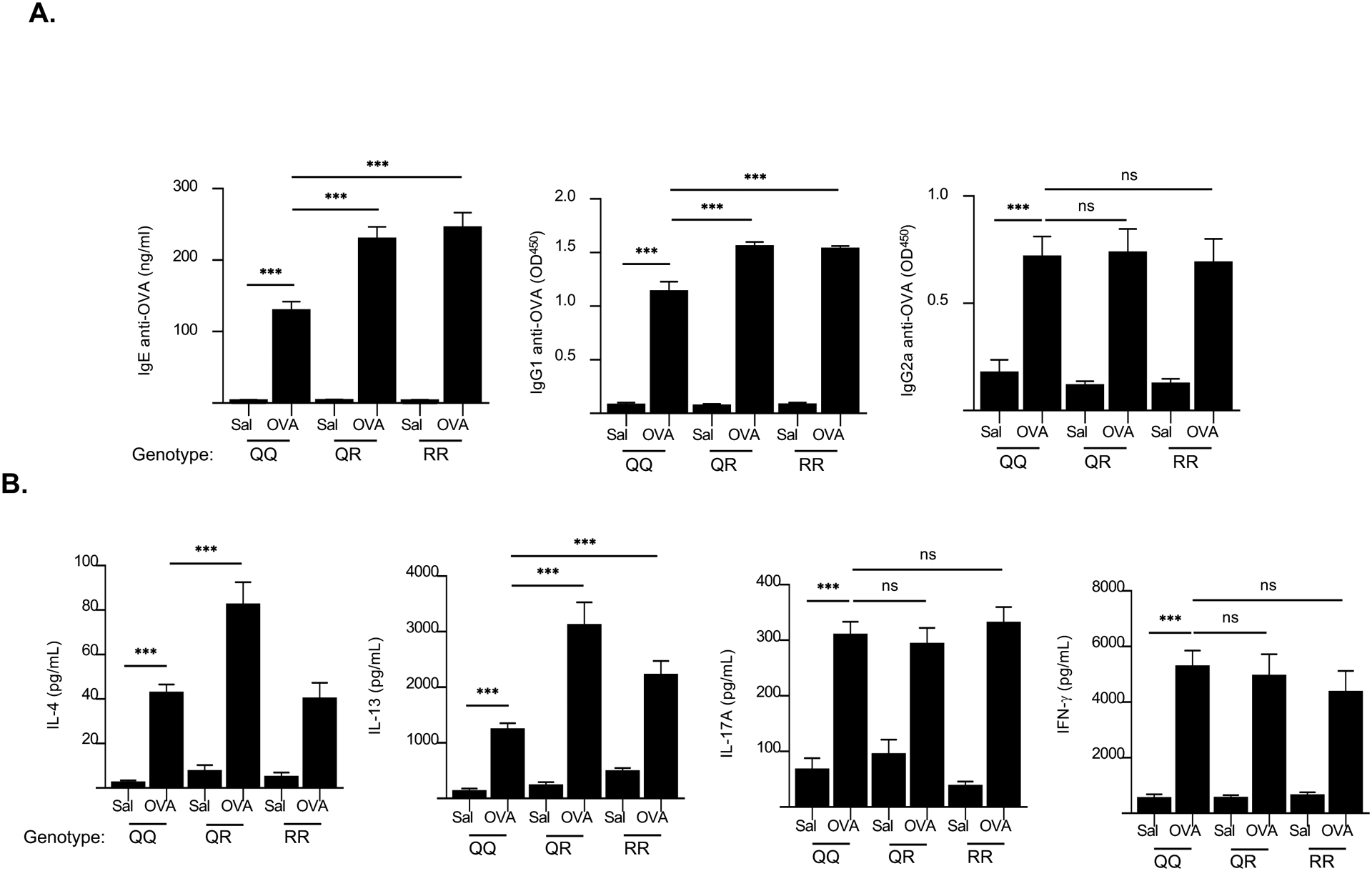

EC sensitization elicits a strong systemic antigen specific Th2 response evidenced by significantly higher serum levels of antigen-specific IgE and IgG1 antibody, and by splenocyte secretion of Th2 cytokines in response to antigen restimulation in vitro23, 25, 32. Serum levels of OVA-specific IgE and IgG1, but not IgG2a, were significantly higher in QR and RR mice compared to QQ WT controls (Fig. 4A). Moreover, splenocytes from OVA sensitized QR and RR mice secreted significantly more IL-13 but not IL-17A or IFNγ, following OVA stimulation in vitro compared to splenocytes from QQ WT controls (Fig. 4B). Significantly higher IL-4 secretion was also observed in QR mice compared to controls (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism causes in a dominant manner an enhanced systemic Th2 response to cutaneously introduced allergens.

Figure 4. Enhanced antigen-specific systemic Th2 response following EC sensitization with OVA of QQ, QR and RR mice.

A, B. Serum OVA-specific IgE, IgG1 and IgG2a levels (A), and secretion of IL-4, IL-13, IL-17A and IFN- γ by OVA-stimulated splenocytes (B) in saline-sensitized and OVA-sensitized skin of QQ, QR and RR mice. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments with 4–5 mice/group. Columns and bars represent mean ± SEM. *** p<0.001, ns = not significant, by one-way ANOVA.

We had previously shown that WT mice EC sensitized with OVA develop airway inflammation after inhaled antigen challenge25 and systemic anaphylaxis after oral antigen challenge41. The responses of RR mice that had been EC sensitized with OVA to oral challenge as to airway challenge with OVA were comparable to those of WT controls (Fig. E1). This suggests that in our model of allergic skin inflammation the effect of the R allele is exerted predominantly at the site of immunization i.e. the skin.

The exaggerated Th2 response of mice carrying the IL-4Ra R576 alleles was not specific to EC sensitization. Following intraperitoneal (i.p.) immunization with OVA and alum, serum levels of OVA-specific IgE and IgG1, but not IgG2a, were significantly higher in QR and RR mice compared to QQ WT controls (Fig. E2A). Moreover, splenocytes from QR and RR mice i.p. immunized with OVA secreted significantly more IL-13, but not IFN-γ, following OVA stimulation in vitro compared to splenocytes from QQ WT controls (Fig. E2B).

The exaggerated allergic skin inflammation and systemic Th2 response to EC sensitization of mice carrying the IL-4Ra R576 allele is not specific to OVA antigen.

To examine whether the exaggerated allergic skin inflammation of RR mice to EC sensitization is antigen specific, RR mice and QQ controls were EC sensitized with house dust mite (HDM) antigen. RR mice demonstrated exaggerated allergic skin inflammation compared to QQ controls, evidenced by significantly increased skin infiltration by CD45+ cells, CD4+T cells and eosinophils, and higher Il4 and Il13, but not Il17a or Ifng expression (Fig. E3A–B). HDM stimulated splenocytes from RR mice EC sensitized with HDM antigen secreted significantly more IL-4 and IL-13, but not IL-17A or IFNγ, compared to QQ controls, (Fig. E3C).

Hematopoietic cells contribute to the increased allergic skin inflammation and systemic Th2 response to EC sensitization in IL-4RαR576 mice.

Both hematopoietic cells and stromal cells express IL4Rα. We used bone marrow (BM) radiation chimeras to determine whether aberrant signaling by the IL-4RαR576 mutant in hematopoietic cells, stromal cells or both results in exaggerated allergic skin inflammation in response to EC sensitization with antigen. BM chimeras were constructed as we previously described using BM donors and irradiated recipients mismatched for expression of CD45.2 and CD45.134. Recipients were EC sensitized 9 weeks after adoptive BM transfer

To assess the contribution of hematopoietic cells to the exaggerated response of RR mice to EC sensitization BM from CD45.2 RR or QQ donors was adoptively transferred into irradiated CD45.1 QQ WT recipients. Eight weeks after adoptive transfer of BM cells donor chimerism in CD45+ cells from blood and skin was 72.8±8.2 % and 65.5%±2.3 % (mean+/− SEM, n=6) respectively in QQ recipients of BM from QQ donors (Fig. E4A–B). The values for donor chimerism in CD45+ cells from blood and skin were 89.7±2.3% and 73.7 %±1.1 % (mean+ SEM, n=5) in QQ recipients of BM from RR donors (Fig. E4A–B). The less robust donor chimerism in skin CD45+ cells is likely due to the presence of skin resident radioresistant hematopoietic cells, e.g. Langerhans cells and subsets of dermal macrophages and dendritic cells42.

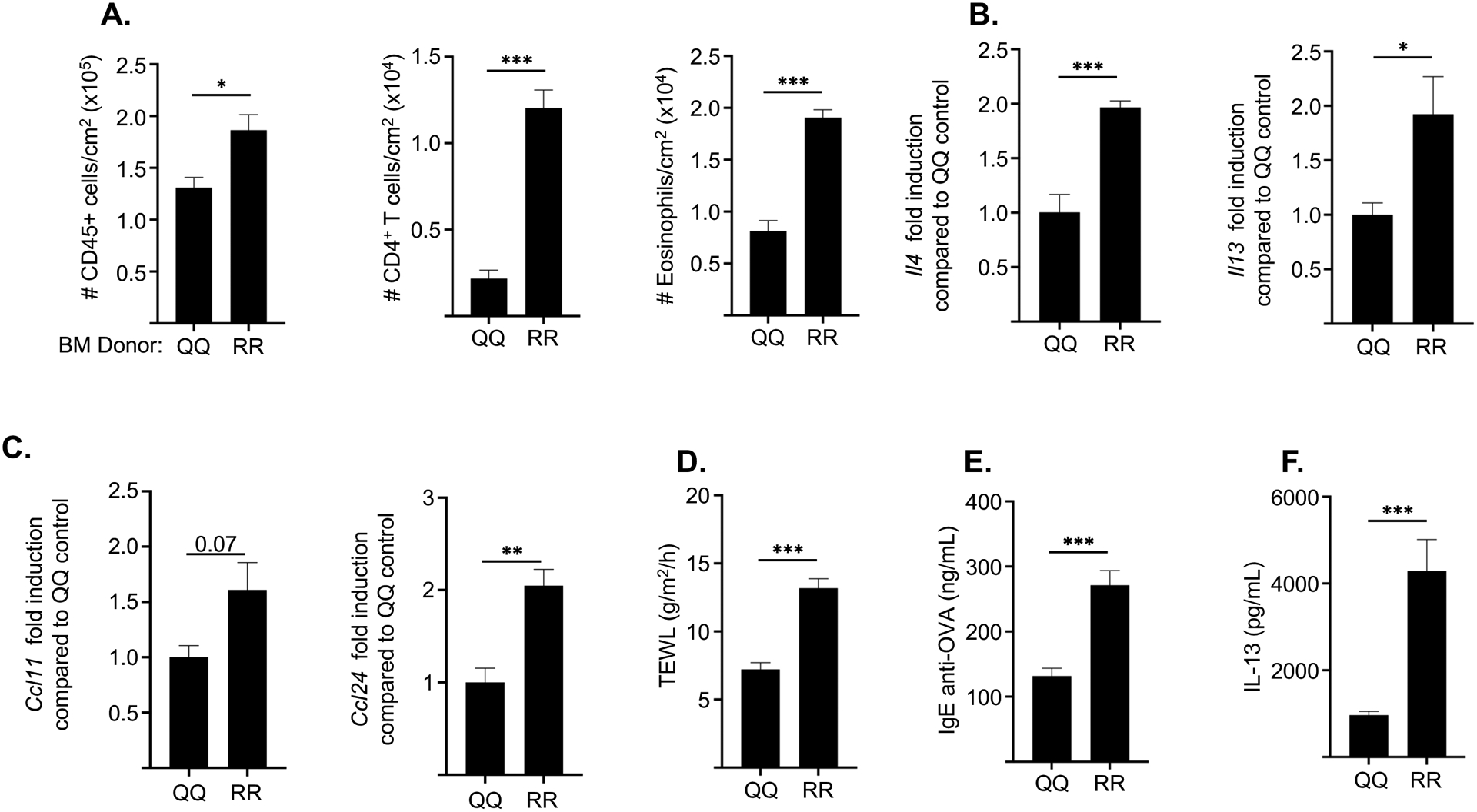

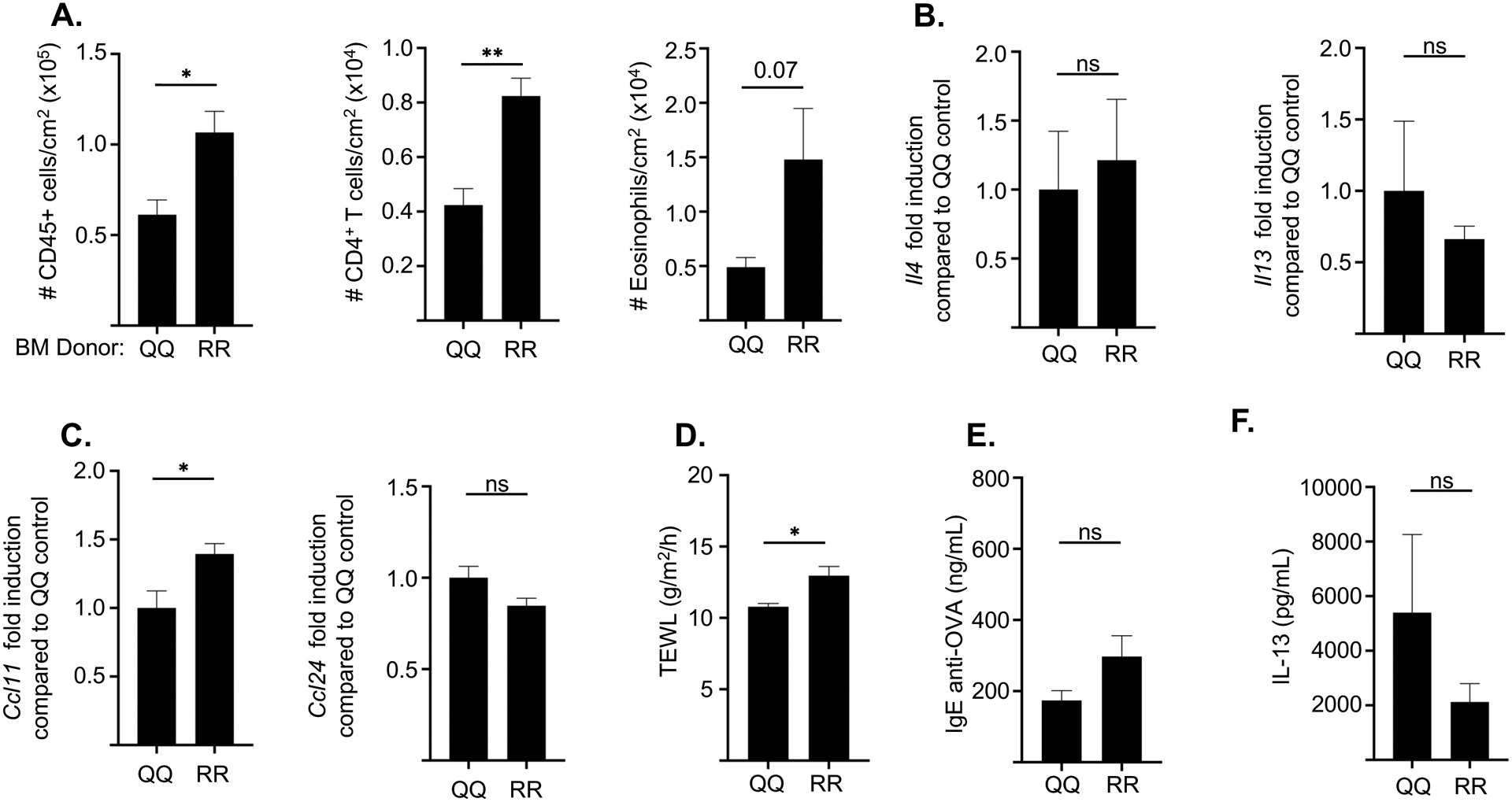

Following EC sensitization with OVA, RR->QQ chimeras demonstrated significantly more allergic skin inflammation compared to QQ->QQ control chimeras. This was evidenced by significantly increased skin infiltration by CD45+ cells, CD4+ T cells and eosinophils, significantly higher expression of Il4 and Il13, but not Il17a or Ifng (Fig. 5A, B and data not shown). There was also higher expression of Ccl11 and Ccl24 encoding eotaxins (Fig. 5C). TEWL was also significantly higher in RR->QQ chimeras compared to QQ->QQ control chimeras (Fig. 5D). In addition, RR->QQ chimeras demonstrated a more robust antigen-specific systemic Th2 response evidenced by significantly higher serum levels of OVA specific IgE antibody and significantly higher secretion of IL-13, but not IL-17A or IFN-γ, by OVA stimulated splenocytes compared to QQ->QQ control chimeras (Fig. 5 E,F and data not shown).

Figure 5. Hematopoietic cells contribute to the increased allergic skin inflammation and systemic Th2 response to EC sensitization in RR mice.

A-D. Numbers/cm2 of CD45+ cells, CD4+ T cells and eosinophils (A), mRNA levels of Il4 and Il13 (B), mRNA levels of Ccl11 and Ccl24 (C), and TEWL (D) in OVA-sensitized skin of QQ recipients of BM from QQ and RR donor mice. E, F. Serum OVA-specific IgE levels (E), and secretion of IL-13 by splenocytes (F) in OVA-sensitized QQ recipients of BM from QQ and RR donor mice. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments with 4–5 recipient mice/group. Columns and bars represent mean ± SEM. * p<0.05, ** p<0.005, *** p<0.001 by unpaired two-tailed Student t test.

These results indicate that signaling by the IL-4RαR576 mutant in hematopoietic cells contributes to the exaggerated Th2 dominated allergic skin inflammation and increased systemic Th2 response to EC sensitization in RR mice.

Stromal cells contribute to the increased cellular skin infiltration in EC sensitized skin of IL-4RαR576 mice.

To determine the contribution of non-hematopoietic stromal cells to the exaggerated skin inflammation in antigen sensitized skin of IL-4RαR576 mice BM from CD45.1 WT (QQ) donors were transferred into CD45.2 mutant (RR) or WT (QQ) recipients. Eight weeks after adoptive transfer of BM cells > 90% (n=4) of CD45+ cells in the blood of the both QQ (n-4) and RR (n=5) recipients were CD45.1+ cells of donor origin (Fig. E4C). Donor chimerism in CD45+ skin cells was 95.2%±0.69% (mean+SEM, n=4) for QQ recipients and 91.2%±2.37% (mean+SEM, n=5) for RR recipients of BM from QQ donors (Fig. E4D).

Following EC sensitization with OVA, QQ->RR chimeras demonstrated increased skin infiltration by CD45+ cells, CD4+ T cells and eosinophils compared to QQ->QQ control chimeras (Fig. 6A). Expression of Il4 and Il13 as well as Il17a and Ifng in OVA sensitized skin was comparable in the two chimeras (Fig. 6B and data not shown), Expression of CCcl11 was increased in QQ->RR chimeras consistent with increased eosinophil skin infiltration (Fig. 6C). TEWL was modestly but significantly elevated in QQ->RR chimeras (Fig. 6D). Serum levels of IgE anti-OVA antibodies and secretion of IL-13 by OVA stimulated splenocytes, were also comparable in the two chimeras (Fig. 6 E, F).

Figure 6. Stromal cells contribute to the increased allergic skin inflammation and systemic Th2 response to EC sensitization in RR mice.

A-D. Numbers/cm2 of CD45+ cells, CD4+ T cells and eosinophils (A), mRNA levels of Il4 and Il13 (B), mRNA levels of Ccl11 and Ccl24 (C) and TEWL (D) in OVA-sensitized skin of RR recipients of BM from QQ and RR donor mice. E, F. Serum OVA-specific IgE levels (E), and secretion of IL-13 by splenocytes (F) in OVA-sensitized RR recipients of BM from QQ and RR donor mice. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments with 4–5 recipient mice/group. Columns and bars represent mean ± SEM. * p<0.05, ** p<0.005, *** p<0.001 by unpaired two-tailed Student t test. ns= not significant

These results indicate that signaling by the IL-4RαR576 mutant in stromal cells contributes to the increased accumulation of T cells and eosinophils in OVA sensitized skin of RR mice, but not to the exaggerated Th2 response of these mice.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism is associated in a dominant manner with increased AD severity as evidenced by significantly higher Rajka-Langeland scores. Studies in mice demonstrated that the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism potentiated in a dominant manner allergic skin inflammation and the systemic Th2 response to cutaneously introduced antigen. Both hematopoietic cells and stromal cells contributed to the increased allergic skin inflammation in mice caused by the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism.

We show in two independent cohorts of patients with AD that the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism tends to be, or is associated with increased disease severity. One cohort consisted of 190 children with asthma and AD most of whom were African Americans or Hispanics. In this cohort, increased itching that interfered with sleep was used as an indicator of disease severity. The second cohort consisted of 1176 patients with AD of European ancestry, most of whom were adults. In this cohort R-L and EASI scores were used as indicators of AD severity. In both cohorts the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism exerted dominant and additive effects on disease severity. The difference between patients with the IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism and those without achieved a p value of 0.08 in the first cohort, and of 0.02 and 0.06 for the R-L and EASI scores in the second cohort. R-L score assesses disease severity over time while the EASI score is a snapshot of disease severity. This may explain the difference between the two scores in reaching a significance level of <0.05. Effect strength may also contribute to the difference, which is expected, as AD is a polygenic disease with a multifactorial pathogenesis. Although disease severity assessed by the R-L score was more in the R carriers, serum IgE levels and blood eosinophils were comparable between the genotypes, but AD skin affected in R-carriers suggesting that the effect of the R variant on the Th2 inflammatory response is exerted locally in the skin more than systemically.

The finding that the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism is associated with increased disease severity in AD is consistent with its association with asthma severity13, 15, 43–46. However, unlike in asthma13, 20, 22 , there was no significant gene dosage effect of the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism on disease severity in AD. AD severity is a major risk factor for peanut allergy47. We recently reported that the IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism increases the risk for severe food allergy in these patients21. The increased disease severity in AD patients with the IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism may underlie their increased risk for severe food allergy.

We show that mice with the IL-4Rα R576 mutation demonstrate an exaggerated allergic skin inflammation in response to EC sensitization with OVA as well as HDM antigens. This was evidenced by increased epidermal thickening, increased dermal infiltration withCD4+ T cells and eosinophils, increased expression of Th2 cytokines in the skin and increased TEWL compared to mice homozygous for the WT IL-4Rα Q576 allele. Moreover, a large number of genes that were upregulated in OVA sensitized skin of mice that carried the IL-4Rα R576 mutation compared to WT mice are genes that are upregulated in AD skin lesions. In addition, mice with the IL-4Rα R576 mutation develop an exaggerated systemic Th2 response to both OVA as well as HDM antigen. These findings further support a causal link between the IL-4Rα R576Q polymorphism and the severity of allergic skin inflammation in a mouse model that shares many characteristics with AD, including epidermal thickening, dermal infiltration by CD4+ T cells and eosinophils, increased expression of Th2 cytokines in the skin and increased TEWL and a systemic Th2 response to cutaneously introduced antigen. The response of RR mice that had been EC sensitized with OVA to oral or airway challenge with OVA were not significantly increased. This suggests that, like in patients R allele is exerts its effect predominantly at the skin immunization site.

We previously reported that the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism is associated with a mixed TH2/TH17 cell inflammation in human asthmatics and in an experimental model of HDM antigen driven mouse allergic inflammation and with the presence of IL-17 producing T regulatory (Treg) cells in lung tissues due to increased Notch4 expression by Tregs20, 48. In contrast, using OVA as well as the same lot of HDM antigen we used in our previous study we found no evidence of increased Il17a expression in the OVA sensitized skin of mice with the IL-4Rα R576 mutation compared to WT controls. This is despite the fact that Treg cells account for more than half of the CD4+ T cells in the skin49, 50 and highly express RORα which synergizes with RORγt to promote IL-17 expression50, 51. Moreover, the Th17 response to i.p. immunization with OVA and HDM antigens was comparable in mice with the IL-4Rα R576 mutation and WT controls. These findings suggest that the tissue environment and/or the route of immunization may determine the generation of an increased Th17 response in the mutant mice.

Our studies using bone marrow chimeras revealed that expression of the IL-4Rα R576 mutant in hematopoietic cells was sufficient to result in exaggerated allergic skin inflammation in OVA sensitized skin and in an exaggerated systemic Th2 response to EC sensitization with OVA. Expression of the IL-4Rα R576 mutant in stromal cells resulted in increased dermal infiltration with CD45+ cells CD4+ T cells and eosinophils and increased TEWL but had no detectable effect on the Th2 response. The exaggerated cellular infiltration could be due in part to increased production of chemokines by stromal cells which express mutant IL-4Rα in response to normal levels of Th2 cytokines, as demonstrated for Ccl11. It is also possible that aberrant signaling via mutant IL-4Rα may result in abnormal cellular trafficking to inflamed skin that results in a greater accumulation of inflammatory cells. The precise contribution of individual cell lineages to the exaggerated allergic skin inflammation in mice with the IL-4Rα R576 mutation requires the construction of mice with lineage selective expression of the IL-4Rα mutant.

A weakness of our study is the limited number of AD patients on whom genotypic data and data on night-time itching were available. This may have contributed to the failure to observe a statistical difference between R carriers and non-carriers in the frequency of night-time itching that interfered with sleep (p=0.08). Further, the EASI scores of R carriers and non-carriers in the ADRN study came close to but did not achieve statistical significance (p=0.06), possibly because many of these patients were on multiple therapies at the time they were examined and/or because of the numbers studied.

In summary, our study demonstrates that the IL4Rα R576 polymorphism results in more severe AD and adds the IL4Rα R576 variant to FLG mutations and early onset disease as predictor of AD severity52. Studies are needed to determine whether patients with this polymorphism are more resistant to IL4Rα blockade and thus are more likely to require higher doses of anti-IL4Rα blocking mAb and/or complementary therapies. Of note, since the IL4Rα R576 variant does not alter JAK/STAT6 signaling the response to JAK inhibitors should be intact in the carriers

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

The IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism is associated with increased disease severity in patients with AD.

The IL4Rα R576 polymorphism exaggerates allergic skin inflammation, barrier dysfunction, and the Th2 systemic response in mice EC sensitized with antigen.

Both hematopoietic cells and stromal cells contribute to the exaggerated allergic skin inflammation in mice that carry the IL-4Rα R576 polymorphism

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIAID/NIH Atopic Dermatitis Research Network (ADRN) (1UM1AI151958). BY was supported by NIAID T-32 training grant T32 AI007306. J.M.L.C. was supported by NIAID T32 training grant (5T32AI007512-32), Boston Children’s Hospital OFD/BTREC/CTREC Faculty Career Development Fellowship and support from Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH (award UL1 TR002541), and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. We thank Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center in Boston, MA, for the service provided by the Rodent Histopathology Core. Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center is supported in part by a NCI Cancer Center Support Grant # NIH 5 P30 CA06516.

Abbreviations

- AD

Atopic dermatitis

- ADRN

Atopic Dermatitis Research Network

- BM

Bone marrow

- EASI

Eczema area and severity index

- EC

Epicutaneous

- GRB2

Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2

- HDM

House dust mite

- IL-4

Interleukin 4

- IL-13

Interleukin 13

- IL-17A

Interleukin 17A

- IL-4Rα

Interleukin 4 receptor alpha

- IFN-γ

Interferon γ

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- MAP kinase

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- OVA

Ovalbumin

IL-4Rα Q576 homozygous

- QR

IL-4Rα Q576/R576 heterozygous

- SICAS

School Inner-city Asthma Study

- R-L

Rajka-Langeland

- RR

IL-4Rα R576 homozygous

- TEWL

Transepidermal water loss

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests.

The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Bieber T Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1483–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. Atopic dermatitis: a disease of altered skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Immunol Rev 2011; 242:233–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irvine AD, McLean WH. Breaking the (un)sound barrier: filaggrin is a major gene for atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2006; 126:1200–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Zhao Y, Liao H, Lee SP, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet 2006; 38:441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin H, He R, Oyoshi M, Geha RS. Animal models of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129:31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pichard DC, Freeman AF, Cowen EW. Primary immunodeficiency update: Part I. Syndromes associated with eczematous dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73:355–64; quiz 65–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck LA, Thaci D, Hamilton JD, Graham NM, Bieber T, Rocklin R, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes KC. An update on the genetics of atopic dermatitis: scratching the surface in 2009. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 125:16–29 e1–11; quiz 30–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bin L, Leung DY. Genetic and epigenetic studies of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2016; 12:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatila TA. Interleukin-4 receptor signaling pathways in asthma pathogenesis. Trends Mol Med 2004; 10:493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hershey GK, Friedrich MF, Esswein LA, Thomas ML, Chatila TA. The association of atopy with a gain-of-function mutation in the alpha subunit of the interleukin-4 receptor. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1720–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosa-Rosa L, Zimmermann N, Bernstein JA, Rothenberg ME, Khurana Hershey GK. The R576 IL-4 receptor alpha allele correlates with asthma severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 104:1008–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenzel SE, Balzar S, Ampleford E, Hawkins GA, Busse WW, Calhoun WJ, et al. IL4R alpha mutations are associated with asthma exacerbations and mast cell/IgE expression. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175:570–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandford AJ, Chagani T, Zhu S, Weir TD, Bai TR, Spinelli JJ, et al. Polymorphisms in the IL4, IL4RA, and FCERIB genes and asthma severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 106:135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ober C, Leavitt SA, Tsalenko A, Howard TD, Hoki DM, Daniel R, et al. Variation in the interleukin 4-receptor alpha gene confers susceptibility to asthma and atopy in ethnically diverse populations. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 66:517–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caggana M, Walker K, Reilly AA, Conroy JM, Duva S, Walsh AC. Population-based studies reveal differences in the allelic frequencies of two functionally significant human interleukin-4 receptor polymorphisms in several ethnic groups. Genet Med 1999; 1:267–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanobetti A, Ryan PH, Coull B, Brokamp C, Datta S, Blossom J, et al. Childhood Asthma Incidence, Early and Persistent Wheeze, and Neighborhood Socioeconomic Factors in the ECHO/CREW Consortium. JAMA Pediatr 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold DR, Wright R. Population disparities in asthma. Annu Rev Public Health 2005; 26:89–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massoud AH, Charbonnier LM, Lopez D, Pellegrini M, Phipatanakul W, Chatila TA. An asthma-associated IL4R variant exacerbates airway inflammation by promoting conversion of regulatory T cells to TH17-like cells. Nat Med 2016; 22:1013–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banzon TM, Kelly MS, Bartnikas LM, Sheehan WJ, Cunningham A, Harb H, et al. Atopic Dermatitis Mediates the Association Between an IL4RA Variant and Food Allergy in School-Aged Children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai PS, Massoud AH, Xia M, Petty CR, Cunningham A, Chatila TA, et al. Gene-environment interaction between an IL4R variant and school endotoxin exposure contributes to asthma symptoms in inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141:794–6 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leyva-Castillo JM, Galand C, Mashiko S, Bissonnette R, McGurk A, Ziegler SF, et al. ILC2 activation by keratinocyte-derived IL-25 drives IL-13 production at sites of allergic skin inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145:1606–14 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyva-Castillo JM, Sun L, Wu SY, Rockowitz S, Sliz P, Geha RS. Single-cell transcriptome profile of mouse skin undergoing antigen-driven allergic inflammation recapitulates findings in atopic dermatitis skin lesions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spergel JM, Mizoguchi E, Brewer JP, Martin TR, Bhan AK, Geha RS. Epicutaneous sensitization with protein antigen induces localized allergic dermatitis and hyperresponsiveness to methacholine after single exposure to aerosolized antigen in mice. J Clin Invest 1998; 101:1614–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheehan WJ, Permaul P, Petty CR, Coull BA, Baxi SN, Gaffin JM, et al. Association Between Allergen Exposure in Inner-City Schools and Asthma Morbidity Among Students. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171:31–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phipatanakul W, Koutrakis P, Coull BA, Petty CR, Gaffin JM, Sheehan WJ, et al. Effect of School Integrated Pest Management or Classroom Air Filter Purifiers on Asthma Symptoms in Students With Active Asthma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021; 326:839–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phipatanakul W, Koutrakis P, Coull BA, Kang CM, Wolfson JM, Ferguson ST, et al. The School Inner-City Asthma Intervention Study: Design, rationale, methods, and lessons learned. Contemp Clin Trials 2017; 60:14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phipatanakul W, Bailey A, Hoffman EB, Sheehan WJ, Lane JP, Baxi S, et al. The school inner-city asthma study: design, methods, and lessons learned. J Asthma 2011; 48:1007–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tachdjian R, Mathias C, Al Khatib S, Bryce PJ, Kim HS, Blaeser F, et al. Pathogenicity of a disease-associated human IL-4 receptor allele in experimental asthma. J Exp Med 2009; 206:2191–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leisten S, Oyoshi MK, Galand C, Hornick JL, Gurish MF, Geha RS. Development of skin lesions in filaggrin-deficient mice is dependent on adaptive immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131:1247–50, 50 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He R, Oyoshi MK, Jin H, Geha RS. Epicutaneous antigen exposure induces a Th17 response that drives airway inflammation after inhalation challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:15817–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galand C, Leyva-Castillo JM, Yoon J, Han A, Lee MS, McKenzie ANJ, et al. IL-33 promotes food anaphylaxis in epicutaneously sensitized mice by targeting mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138:1356–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon J, Leyva-Castillo JM, Wang G, Galand C, Oyoshi MK, Kumar L, et al. IL-23 induced in keratinocytes by endogenous TLR4 ligands polarizes dendritic cells to drive IL-22 responses to skin immunization. J Exp Med 2016; 213:2147–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bender BG, Ballard R, Canono B, Murphy JR, Leung DY. Disease severity, scratching, and sleep quality in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 58:415–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawada T Atopic Dermatitis and Sleep Disturbance in Adults. Dermatitis 2017; 28:328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramirez FD, Chen S, Langan SM, Prather AA, McCulloch CE, Kidd SA, et al. Association of Atopic Dermatitis With Sleep Quality in Children. JAMA Pediatr 2019; 173:e190025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunner PM, Israel A, Leonard A, Pavel AB, Kim HJ, Zhang N, et al. Distinct transcriptomic profiles of early-onset atopic dermatitis in blood and skin of pediatric patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2019; 122:318–30 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ewald DA, Malajian D, Krueger JG, Workman CT, Wang T, Tian S, et al. Meta-analysis derived atopic dermatitis (MADAD) transcriptome defines a robust AD signature highlighting the involvement of atherosclerosis and lipid metabolism pathways. BMC Med Genomics 2015; 8:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khattri S, Brunner PM, Garcet S, Finney R, Cohen SR, Oliva M, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol 2017; 26:28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bartnikas LM, Gurish MF, Burton OT, Leisten S, Janssen E, Oettgen HC, et al. Epicutaneous sensitization results in IgE-dependent intestinal mast cell expansion and food-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131:451–60 e1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Wagers A, Loubeau M, Isola LM, Lubrano L, et al. Identification of a radio-resistant and cycling dermal dendritic cell population in mice and men. J Exp Med 2006; 203:2627–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nie W, Zang Y, Chen J, Xiu Q. Association between interleukin-4 receptor alpha chain (IL4RA) I50V and Q551R polymorphisms and asthma risk: an update meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013; 8:e69120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loza MJ, Chang BL. Association between Q551R IL4R genetic variants and atopic asthma risk demonstrated by meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120:578–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hytonen AM, Lowhagen O, Arvidsson M, Balder B, Bjork AL, Lindgren S, et al. Haplotypes of the interleukin-4 receptor alpha chain gene associate with susceptibility to and severity of atopic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2004; 34:1570–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deichmann K, Bardutzky J, Forster J, Heinzmann A, Kuehr J. Common polymorphisms in the coding part of the IL4-receptor gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 231:696–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keet C, Pistiner M, Plesa M, Szelag D, Shreffler W, Wood R, et al. Age and eczema severity, but not family history, are major risk factors for peanut allergy in infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 147:984–91 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benamar M, Harb H, Chen Q, Wang M, Chan TMF, Fong J, et al. A common IL-4 receptor variant promotes asthma severity via a Treg cell GRB2-IL-6-Notch4 circuit. Allergy 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanchez Rodriguez R, Pauli ML, Neuhaus IM, Yu SS, Arron ST, Harris HW, et al. Memory regulatory T cells reside in human skin. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:1027–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malhotra N, Leyva-Castillo JM, Jadhav U, Barreiro O, Kam C, O’Neill NK, et al. RORalpha-expressing T regulatory cells restrain allergic skin inflammation. Sci Immunol 2018; 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang XO, Pappu BP, Nurieva R, Akimzhanov A, Kang HS, Chung Y, et al. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR alpha and ROR gamma. Immunity 2008; 28:29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holm JG, Agner T, Clausen ML, Thomsen SF. Determinants of disease severity among patients with atopic dermatitis: association with components of the atopic march. Arch Dermatol Res 2019; 311:173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.