Abstract

A widely held belief is that autocratic governments have been more effective in reducing the movement of people to curb the spread of COVID-19. Using daily information on lockdown measures and geographic mobility across more than 130 countries, we find that autocratic regimes have indeed imposed more stringent lockdowns and relied more on contact tracing. However, we find no evidence that autocratic governments were more effective in reducing travel, and evidence to the contrary: compliance with the lockdown measures taken was higher in countries with democratically accountable governments. Exploring a host of potential mechanisms, we provide suggestive evidence that democratic institutions are associated with attitudes that support collective action, such as mounting a coordinated response to a pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Democracy, Autocracy, Policy compliance, Social capital

1. Introduction

In Democracy in America, Tocqueville (2000) famously pointed to the importance of a robust civil society for the functioning of democracy. In similar spirit, modern day scholars have noted that democracy works better in places with higher levels of social capital (Fukuyama, 1996, Putnam, 1993). For one thing, generalized trust facilitates cooperation among larger groups, allowing democracies to solve collective action problems on a voluntary basis (Algan and Cahuc, 2014). In autocracies, in contrast, collective action depends on the power of the dictator. And this pattern is reinforced by the fact that autocracies have limited social capital to rely on. Xue and Koyama (2019) and Xue (2021), for example, identify an equilibrium in which autocracies have a lower level of social capital due to political repression, which in turn cements autocracy through the provision of fewer public goods and less political participation. This, however, constrains the manoeuvring space of the dictator, who in the absence of voluntary compliance must rely on the capacity of the state to get policy implemented.1

In this paper, we explore these ideas in the context of COVID-19 policy compliance. Our theory leads us to predict that less democratic states will take more stringent policy measures to make up for the lack of voluntary collective action.2 To test this, we use daily information on mobility trends and policy restrictions in 132 countries, from the beginning to the peak in policy stringency during the first wave of the pandemic, allowing us to estimate the differential responses and their effectiveness in reducing geographic mobility across democratic and authoritarian states. Doing so, we document two remarkably robust empirical regularities. (1) To curb the movement of people, which risks spreading the virus, autocracies around the world have introduced more stringent lockdown measures. (2) However, democracies have seen higher levels of policy compliance, and so achieved similar outcomes despite their less repressive measures.

In our empirical analysis, as a first step, we regress an index of restrictions on mobility on daily confirmed cases of COVID-19, as well COVID-related deaths, and their interaction with a proxy for whether a country is democratic. Exploiting time variation in policy and infections, we are able to include country fixed effects and purge our estimates from country-specific characteristics potentially affecting the spread of the virus and the policy response. Though not a panacea for all sources of omitted variable bias and endogeneity concerns, we document a robust and negative correlation between democracy and policy stringency: for a given number of infections, the policy stringency index is 5% lower in the most consolidated democracies relative to other countries.

Second, we regress changes in people’s mobility on policy stringency and its interaction with proxies for democracy. Consistent with the previous result, we find that reducing mobility required substantially less policy stringency in democratic countries. The elasticity of geographic mobility to policy stringency is between 13% and 34% larger in countries with democratically accountable governments, for the same level of policy stringency and a comparable spread of infections. Taken together, these findings speak to our intuition that by having lower levels of social capital on average, autocracies compensate with a higher level of policy stringency. Put differently, democracies did not need as many restrictions to control the pandemic.

To shed further light on this issue, we next explore the potential underlying mechanisms driving the relationship between democracy and compliance. Doing so, we are able to rule out a host of factors, including having a more generous welfare system, greater public goods provision, better access to information, and higher levels of state capacity. The only variable that is associated with higher policy compliance, keeping policy stringency constant, is social capital, as measured by generalized trust. We also show that on average, social capital is around 30%, higher among democracies. This lends further support to the hypothesis that autocracies needed more heavy-handed measures to reduce mobility because of their relatively low levels of social capital (Xue, & Koyama, Xue).

Our paper relates to two literatures. First, we join the rapidly growing strand of research examining how populations and policymakers around the world have responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in general (e.g. Ajzenman, Cavalcanti, Mata, 2020, Bargain, Aminjonov, 2020, Barrios, et al., 2021, Bonacini, Gallo, Patriarca, 2020, Chen, Frey, Presidente, 2021, Gutierrez, Rubli, Tavares, 2020, Wright, et al., 2020), and a subset of this literature focusing on the role of culture in particular (Barrios, et al., 2021, Chen, Frey, Presidente, 2021). For example, in the U.S. context, Barrios et al. (2021) show that voluntary social distancing is associated with higher levels of civic capital. In contrast, Chen et al. (2021) document lower levels of policy compliance in places where people are more individualistic. However, despite having the opposite effect on peoples’ response to the pandemic, both individualism and civic capital are intimately associated with robust democracy (Almond, Verba, 1963, Banfield, 1958, Gorodnichenko, Roland, 2021, Nannicini, Stella, Tabellini, Troiano, 2013), making the direction of the relationship between democracy and policy compliance a priori unclear. We add to this literature by showing that democracies exhibit higher levels of policy compliance on average.

Second, we build on a large and established literature investigating the role of soft power, like culture, beliefs, and norms (e.g., Alesina, Giuliano, 2015, Guiso, Sapienza, Zingales, 2016, Putnam, 1993, Nye Jr, 2004, Tabellini, 2008), and hard power, like state capacity (Besley, 2020, Besley, Persson, 2009, Fukuyama, F. (2014), Fukuyama, 2015, Johnson, Koyama, 2017), in shaping policymaking and economic development. For example, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Fukuyama (2020) has argued that the “major dividing line in effective crisis response will not place autocracies on one side and democracies on the other”, but the state’s capacity. In this paper, however, we find no empirical support for the idea that the bureaucratic or fiscal capacity of the state is associated with higher policy compliance at a given level of policy stringency. Instead, our findings point to the importance of the soft power democracies have in solving collective action problems, such as mounting a coordinated response to a pandemic.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 details the construction of our dataset. In Section 3, we discuss our empirical strategy and the determinants of policy stringency. Section 4 describes our methodology and explores the elasticity of geographic mobility to policy stringency, as well as potential underlying mechanisms. Finally, in Section 5, we outline our conclusions.

2. Data

We begin by building a dataset that allows us to trace the daily spread of COVID-19 cases, government’s response to the pandemic, and the movement of people across 132 countries from the beginning to the peak of the first lockdown period.3 Data on mobility were collected from Google’s Community Mobility Reports, and matched with information on policy restrictions, testing, and tracing from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) (Hale et al., 2020).

The Google Community Mobility Reports provide daily data on Google Maps users who have opted-in to the “location history” in their Google accounts settings across 132 countries. The reports calculate changes in movement compared to a baseline, which is the median value for the corresponding day of the week during the period between the 3rd of January and the 6th of February 2020. The purpose of travel has been assigned to one of the following categories: retail and recreation, groceries and pharmacies, parks, transit stations, and workplaces.4

OxCGRT, on the other hand, contains various lockdown measures for 150 countries, which are compiled into a stringency index that is constantly updated to reflect daily changes in policy. The index—which is an average of eight sub-indicators, including stay-at-home orders, school, workplace and public transport closures, cancellation of public events, and restrictions on gathering size—is a continuous variable taking the value 0 if no restrictions are in place, while 100 corresponds to the highest level of stringency observed across countries at any given point in time. Conveniently, for our purposes, OxCGRT also provides data on testing policy and contact tracing. Unlike the policy stringency index, however, the testing and contract tracing indexes are categorical variables. Specifically, a value of 0 corresponds to no testing policy or contact tracing; 1 corresponds to selected testing (e.g. key workers with symptoms) or limited contact tracing; while 2 corresponds to testing anyone with COVID-19 symptoms or comprehensive contact tracing. If testing policy is conducted at the national-level rather than in selected areas, the testing policy index is augmented by one point.5

To capture democratic institutions, we collect data from different sources. Our main measure of democracy is the widely used Revised Combined Polity Score, from Polity IV (e.g. Benedetto, Hix, Mastrorocco, 2020, Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson, Yared, 2008, Papaioannou, Siourounis, 2008, Kostelka, 2017).6 The continuous variable captures the full spectrum of political regimes on a scale ranging from -10 (hereditary monarchy) to +10 (consolidated democracy). To ease interpretation, we normalise the index to have zero mean and unitary standard deviation across the sample.7 The variable captures key aspects of both democracies and autocracies, and combines them into a single index. The underlying logic is that in a given country, patterns of autocracy and democracy can co-exist. The democratic features of the index are the presence of institutions and procedures through which citizens can express preferences about policies and leaders, constraints on the exercise of power by the executive, and the guarantee of civil liberties and political participation.

In addition, we assess the robustness of our results using an additional measure of democracy. This variable is a dummy equal to 1 if a country is classified as autocratic in the Dictatorship Countries Population 2020 Report, compiled by the World Population Review.8 Summary statistics for the variables used in our analysis are provided in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | mean | sd | min | max | |

| Democracy (Polity IV), index | 54,322 | 5.181 | 5.945 | -10 | 10 |

| Autocracy (WPR), dummy | 58,720 | 0.209 | 0.407 | 0 | 1 |

| Confirmed COVID-19 cases, log | 42,240 | 5.659 | 3.287 | 0 | 14.63 |

| COVID-19 related deaths, log | 42,240 | 2.402 | 2.659 | 0 | 11.80 |

| Mobility, index | 47,904 | -18.55 | 31.65 | -97 | 188 |

| Real GDP per capita, log | 56,398 | 9.052 | 1.403 | 5.605 | 11.67 |

| Mobile phone subscriptions per hundred people | 54,696 | 115.7 | 34.74 | 33.46 | 345.3 |

| Transparency and accountability, dummy | 58,777 | 0.0889 | 0.285 | 0 | 1 |

| Experience with previous epidemics, dummy | 58,720 | 0.0681 | 0.252 | 0 | 1 |

| Contact tracing, index | 52,987 | 0.834 | 0.830 | 0 | 2 |

| Testing, index | 53,170 | 0.986 | 0.851 | 0 | 3 |

| Extent of welfare system, index | 37,584 | 5.481 | 1.705 | 2 | 9.500 |

| Human capital, index | 45,681 | 2.772 | 0.652 | 1.205 | 3.809 |

| Tax revenue, % GDP | 43,139 | 16.76 | 6.717 | 0.0435 | 37.75 |

| Bureaucratic quality, index | 56,308 | 0.683 | 1.197 | -2.001 | 3.371 |

| Generalised trust, index | 23,040 | 1.758 | 0.166 | 1.326 | 1.972 |

| Voting in national elections, index | 22,556 | 1.537 | 0.297 | 1.061 | 2.766 |

| Individuals using the Internet, % population | 49,953 | 55.96 | 27.65 | 4.323 | 98.24 |

Sources: Google Community Mobility Reports; OxCGRT; Polity IV; World Population Review; World Value Survey v6; World Bank; Quality of Government Dataset.

3. Political regimes and COVID-19 policy

To assess whether autocratic governments tend to implement more stringent mobility restrictions, we estimate OLS regressions of the following form:

| (1) |

Specification (1) assumes that policy stringency in country and date , depends on the contemporaneous impact of COVID-19, . The variable is the log number of daily confirmed cases of infection. This specification allows policy to vary between democratic and autocratic countries, which are proxied by .

A major concern with specification (1) is that is subject to measurement errors. For instance, the number of daily confirmed cases might be reported with delays (Bonacini, Gallo, Patriarca, 2020, Gutierrez, Rubli, Tavares, 2020), possibly due to differences in the availability of tests (Wälde, 2020). We tackle the issue by including a country-specific time varying index of testing policy, . However, measurement errors might also systematically evolve over time due to better knowledge of the virus and improvements in diagnostic tools, which is taken into account by the inclusion of date fixed effects, . But politicians may also purposely misreport COVID-19 cases to downplay the epidemic (Ajzenman et al., 2020). To mitigate this concern, we report results obtained with COVID-related deaths, which should be harder to conceal, making underreporting less likely to occur than with cases. Moreover, in all specifications we include country fixed effects, , which eliminate any systematic misreporting of cases in a given country. In addition to misreporting, given the high frequency of the daily data used in our analysis, country fixed effects absorb country-specific confounders such as differences in economic development.

While our strategy should account for the presence of country-specific bias, measurement errors might be systematically related to being an autocratic country—i.e., a low value of . In particular, autocracies might be more likely to underreport cases, which would inflate the interaction coefficient in model (1). To alleviate this concern, we interact the number of COVID-19 cases or deaths with a dummy variable equal to 1 if a country scores below the average sample value of an index of transparency, accountability, and corruption in the public sector from the World Bank, across all specifications.9

One final concern is that autocratic countries (with a low value of ) are poorer than democracies. If economic development is correlated to policy stringency, that might lead to omitted variable bias. To address such concerns, unless differently stated, all specifications control for the interaction between , the logarithm of real GDP per capita, as well as the number of mobile phone subscriptions per hundred people. Building on the intuition that countries that were exposed to SARS or MERS have managed COVID-19 more effectively, we also include an interaction between and a dummy for experience with these past epidemics. Because varies at the country level, we cluster standard errors accordingly.

3.1. Democracy and policy stringency: Results

The OLS coefficient in column 1 of Table 2 suggests that on average, a doubling of COVID-19 cases is associated with a roughly 5% increase in policy stringency. In column 2, we find that a doubling of confirmed COVID-19 infections is associated with an around 6% decline in policy stringency in the most consolidated democracies relative to countries with an average democracy score.10 In column 3, we replace the Polity index of democracy with a dummy equal to 1 if the World Population Review flags a country as undemocratic. Reassuringly, our results are unchanged. The last two columns of Table 2 report the results obtained by replacing confirmed cases with deaths from COVID-19, which might be less subject to underreporting. We note that the results are very similar.

Table 2.

Determinants of policy stringency: the role of democratic institutions.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy stringency | Policy stringency | Policy stringency | Policy stringency | Policy stringency | |

| Log number of COVID-19 cases | 0.0467*** | 0.0973*** | 0.110*** | ||

| [0.00910] | [0.0220] | [0.0205] | |||

| Cases democracy (Polity) | -0.00533*** | ||||

| [0.00167] | |||||

| Cases autocracy (WPR) | 0.0122*** | ||||

| [0.00416] | |||||

| Log number of COVID-19 deaths | 0.0665** | 0.0860*** | |||

| [0.0272] | [0.0280] | ||||

| Deaths democracy (Polity) | -0.00943*** | ||||

| [0.00313] | |||||

| Deaths autocracy (WPR) | 0.0153** | ||||

| [0.00646] | |||||

| Observations | 11,576 | 8513 | 9126 | 8513 | 9126 |

| R-squared | 0.869 | 0.909 | 0.895 | 0.891 | 0.871 |

| Number of countries | 150 | 118 | 129 | 118 | 129 |

| Controls | |||||

| Country FE | |||||

| Time FE |

Notes: This table presents OLS estimates from regressing the policy stringency index on the log number of COVID-19 infections and COVID-related deaths interacted with the Polity index of democracy (columns 2 and 4), or a dummy equal to 1 if the World Population Review flags a country as autocratic (columns 3 and 6). All specifications include a time varying index of the intensity of testing policy. Columns 2–6 include an interaction between infections and: i) log GDP per capita; ii) mobile phone subscriptions per hundred people; iii) a dummy equal to 1 if a country scores below the average value of an index of government accountability and transparency; and iv) a dummy equal to 1 if a country has experienced more than fifty SARS or MERS cases. Errors are clustered at the country-level. The coefficients with are significant at the 1% level, with are significant at the 5% level, and with are significant at the 10% level.

Moreover, as noted, many pundits have argued that countries like Taiwan and South Korea have benefited from greater experience with past epidemics. To explore this, Table 3 regresses our testing policy index and an index capturing the intensity of contract tracing on the interaction between COVID-19 infections, our measure of democracy, and a dummy for experience with previous epidemics.11 In column 1, we find no statistically significant differences in testing among democratic countries, but countries that experienced SARS or MERS were more likely to implement comprehensive testing policies.12 We further note that autocratic countries were more likely to implement privacy-invasive contact tracing (column 2).13

Table 3.

Determinants of testing policy and contact tracing: the role of democratic institutions and past experience with epidemics.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Testing | Contact tracing | |

| Log number of COVID-19 cases | 0.154 | 0.0762 |

| [0.0933] | [0.0959] | |

| Cases democracy (Polity) | -0.00563 | -0.0213* |

| [0.00917] | [0.0116] | |

| Cases experience with past epidemics | 0.106*** | -0.00926 |

| [0.0272] | [0.0294] | |

| Observations | 8521 | 8394 |

| R-squared | 0.571 | 0.456 |

| Number of countries | 118 | 117 |

| Controls | ||

| Country FE | ||

| Time FE |

Notes: This table presents OLS estimates from regressing indexes of testing (column 1) and contact tracing (column 2) on the log number of COVID-19 infections, and the interaction between cases and previous experience with epidemics. All specifications include an interaction between infections and: i) log GDP per capita; ii) mobile phone subscriptions per hundred people; iii) a dummy equal to 1 if a country scores below the average value of an index of government accountability and transparency. Errors are clustered at the country-level. The coefficients with are significant at the 1% level, with are significant at the 5% level, and with are significant at the 10% level.

Before turning to our main analysis, we also shed some light on the drivers of the differences in policy stringency across democratic nation states. We hypothesize that countries with more developed welfare systems, which reduce people’s exposure to socio-economic risks, might be less reluctant to implement stringent lockdowns. In addition, while no government is immune to public opinion, some leaders might be more fearful of losing support. In particular, when governments have greater trust and public support, they might feel more empowered to take tough decisions.

To explore these ideas, we use a triple interaction between COVID-19 cases, democracy, and one of the following variables: i) the quality of the welfare system, and ii) citizens trust for politicians.14 The results are presented in Table 4 . In column 1, the triple interaction coefficient is positive and significant, suggesting that democracies with more developed welfare systems implemented more stringent lockdowns. The triple interaction coefficient in column 2 is also positive and significant, meaning that among democracies, greater trust for politicians allow governments to introduce more restrictions on movement and travel.

Table 4.

Political economy of COVID-19 responses.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Policy stringency | Policy stringency | |

| Log number of COVID-19 cases | 0.0763*** | 0.101*** |

| [0.00616] | [0.0362] | |

| Cases democracy (Polity) | -0.00776*** | -0.0719*** |

| [0.00213] | [0.0218] | |

| Cases democracy welfare system | 0.000832** | |

| [0.000369] | ||

| Cases democracy trust in politicians | 0.0182*** | |

| [0.00647] | ||

| Observations | 5155 | 2049 |

| R-squared | 0.889 | 0.950 |

| Number of countries | 83 | 20 |

| Controls | ||

| Country FE | ||

| Time FE |

Notes: This table presents OLS estimates from regressing the policy stringency index on the log number of COVID-19 infections interacted with the Polity index of democracy, as well as a triple interaction with measures of the generosity of the welfare state (column 1), and trust in politicians (column 2). All specifications include a time varying index of the intensity of testing policy, an interaction between infections and: i) log GDP per capita; ii) mobile phone subscriptions per hundred people; iii) a dummy equal to 1 if a country scores below the average value of an index of government accountability and transparency; and iv) a dummy equal to 1 if a country has experienced more than fifty SARS or MERS cases. Errors are clustered at the country-level. The coefficients with are significant at the 1% level, with are significant at the 5% level, and with are significant at the 10% level.

4. Political regimes and compliance with COVID-19 policy

In this section, we compare the policy stringency required to reduce mobility in democracies and autocratic regimes. Doing so, we estimate variations of the following linear model:

| (2) |

where, is the mobility index in country , date , and mobility category .15 The coefficient of interest is , which measures the impact of mobility restrictions in countries characterised by varying strength of democratic institutions, which is captured by .

In estimating model (2), we need to address a number of potential issues. First, mobility patterns in some places might be systematically different. Visits to parks, for instance, could be less frequent in countries with a cold or hazardous climate. Also, since mobility data are expressed in relation to a benchmark mobility rate (see Section 2), there is less room for mobility declines in countries with a low benchmark rate. To address this concern, in model (2) we include country-mobility category fixed effects, , to purge our estimates from constant unobserved characteristics of each particular mobility category in a given country. The mobility fixed effects also account for differences in essential and non-essential mobility.16

Second, in order to interpret our estimates of as compliance with policy restrictions, which is the focus of our paper, we compute the elasticity of mobility to policy changes for similar levels of gravity of the pandemic. As shown in Section 3, policy stringency depends on the spread of the virus. Hence, failing to control for the extent of the outbreak might result in omitted variable bias: lower elasticities could simply reflect a lower incidence of COVID-19 infections. For this reason, includes the number of confirmed cases and its interaction with policy stringency.17 However, more concerning in our context: the magnitude of the outbreak and the policy response might be systematically different in democratic and autocratic countries. To that end, in we include the interaction between cases and , as well as a three-way interaction between cases, , and policy stringency.

As in specification (1), we are concerned that model (2) might also be subject to measurement errors in reported cases, which are now used as a control variable. To mitigate this concern, we again include the country-specific, time varying index of testing policy, as well as the interaction between cases and a dummy for the accountability and transparency of government. Still, specification (2) could be subject to measurement errors in our mobility data, as factors related to economic development and democratic institutions might be systematically related to the reliability of Google’s Community Mobility Reports. In particular, we are concerned that if fewer people in autocratic countries own mobile phones and communication infrastructure is less developed, mobility data might be less accurate than in mature democracies. For this reason, includes interactions between policy stringency and the country-level log of GDP per capita as well as the number of mobile phone subscriptions per hundred people. The vector includes the interaction between policy stringency and a dummy for experience with past epidemics, to control for the fact that even in the absence of policy restrictions people in those countries might move around less. Finally, date fixed effects, , account for global and time varying unobserved factors. Because the highest level of variation in model (2) is at the country-level, we cluster errors accordingly.

4.1. Democracy and compliance with COVID-19 policy: Results

How much policy stringency is needed to reduce mobility? Table 5 presents our results from estimating model (2) with OLS. The coefficient in column 1 suggests that on average, a doubling of policy stringency reduced mobility by 5.4%. The coefficients in columns 2 and 3 suggest that the elasticity is larger (in absolute terms) in democracies, as measured by the Polity indicator. The specification in column 2 includes only the policy stringency index and its interaction with our measure of democracy, while column 3 includes the full set of controls discussed in Section 4. The results are similar, implying that even the most parsimonious specification captures the trends of interest. Our preferred specification in column 3 suggests that a doubling of policy stringency is associated to 8% reduction in mobility in countries with an average democracy score ( due to normalisation). In the most consolidated democracies, in contrast, we document a 9.1% reduction on average, implying that at the same level of policy stringency, mobility fell by roughly 13% more.18

Table 5.

Elasticities of mobility to policy stringency: the role of democratic institutions.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | Mobility | Mobility | Mobility | Mobility | |

| Policy stringency | -54.50*** | -54.88*** | -81.03*** | -56.19*** | -86.41*** |

| [4.734] | [4.863] | [20.65] | [4.757] | [23.40] | |

| Policy stringency democracy (Polity) | -3.377** | -10.41** | |||

| [1.701] | [5.234] | ||||

| Policy stringency autocratic country (WPR) | 9.605** | 29.21** | |||

| [4.139] | [12.39] | ||||

| Observations | 39,593 | 37,433 | 25,234 | 39,593 | 26,204 |

| R-squared | 0.708 | 0.706 | 0.666 | 0.710 | 0.661 |

| Number of country-mobility category pairs | 555 | 525 | 490 | 555 | 515 |

| Controls | |||||

| Country FE | |||||

| Time FE |

Notes: This table presents OLS estimates from regressing mobility on the policy stringency index and an interaction between policy stringency and the Polity democracy index (columns 2–3), or a dummy equal to 1 if the World Population Review flags a country as autocratic (columns 4–5). Columns 3, 5 include: i) the number of confirmed cases and its interaction with policy stringency; ii) the interaction between cases and , as well as a three-way interaction between cases, our measure of democracy, and policy stringency; iii) the time varying index of testing policy; iv) the interaction between cases and the dummy for accountability and transparency of the government; v) the interaction between policy stringency and country-level log of GDP per capita; vi) the interaction between policy stringency and the number of mobile phone subscriptions per hundred people; and vii) the interaction between policy stringency and the dummy for experience with previous epidemics. Errors are clustered at the country-level. The coefficients with are significant at the 1% level, with are significant at the 5% level, and with are significant at the 10% level.

For robustness, columns 4 and 5 replace the Polity measure with a dummy equal to 1 if the World Population Review flags a country as undemocratic. We note that our results are qualitatively similar regardless of whether we include the full set of controls. However, the magnitude of the coefficient is larger. Our preferred specification in column 5 suggests that for a similar level of policy stringency, mobility fell by 34% less in autocratic countries.19

In short, our findings suggest that the reason why autocracies have taken more radical measures to reduce the movement of people relative to democracies is precisely that they have been less successful in implementing them. The same level of policy stringency reduced mobility between 13% and 34% more in democracies than in autocratic regimes, depending on the specification.

4.2. Mechanisms

Finally, we shed light on some possible mechanisms driving the variation in compliance across democracies and autocratic regimes. For instance, transfer payments make compliance less costly for individuals, so it stands to reason that countries with more generous welfare systems will exhibit higher levels of compliance. What is more, recent work shows that democracies grow more rapidly, in large part because the expansion of the franchise increases the provision of public goods (Acemoglu et al., 2019), making a reduction in essential movement more affordable to the population relative to autocracies. To assess whether this might drive our results, in column 1 of Table 6 we consider the inclusiveness of countries welfare systems as proxied by a widely used measure from the Quality of Government database (QoG), capturing the extent to which available welfare arrangements compensate for social risks. We note that the interaction between policy stringency and welfare systems around the world is not significant at conventional levels.

Table 6.

Elasticities of mobility to policy stringency: what drives the relationship between democracy and compliance?

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | Mobility | Mobility | Mobility | Mobility | Mobility | |

| Policy stringency | -67.05** | -100.4*** | -99.34*** | -63.22** | -63.30* | -27.98 |

| [31.11] | [24.36] | [25.64] | [25.90] | [33.90] | [22.38] | |

| Policy stringency welfare system (QoG) | 1.007 | |||||

| [2.298] | ||||||

| Policy stringency human capital index (PWT) | 4.632 | |||||

| [7.206] | ||||||

| Policy stringency tax revenue (% GDP) (WB) | -0.0438 | |||||

| [0.530] | ||||||

| Policy stringency bureaucratic quality (VDem) | 3.010 | |||||

| [3.645] | ||||||

| Policy stringency access to Internet (QoG) | 0.361 | |||||

| [0.239] | ||||||

| Policy stringency social capital (WVS) | -12.46*** | |||||

| [4.054] | ||||||

| Observations | 15,815 | 22,114 | 20,564 | 25,234 | 23,089 | 11,605 |

| R-squared | 0.740 | 0.662 | 0.652 | 0.665 | 0.669 | 0.708 |

| Number of country-mobility category pairs | 340 | 435 | 405 | 490 | 450 | 205 |

| Controls | ||||||

| Country FE | ||||||

| Time FE |

Notes: This table presents OLS estimates from regressing mobility on the policy stringency index and an interaction between policy stringency, the Polity democracy index and several variables aimed at explaining the relationship between democracy and compliance. All specifications include: i) the number of confirmed cases and its interaction with policy stringency.; ii) the interaction between cases and , as well as a three-way interaction between cases, our measure of democracy and policy stringency; iii) the time varying index of testing policy; iv) the interaction between cases and a dummy for the accountability and transparency of government; v) the interaction between policy stringency and country-level log of GDP per capita; vi) the interaction between policy stringency and the number of mobile phone subscriptions per hundred people; and vii) the interaction between policy stringency and the dummy for experience with previous epidemics. Errors are clustered at the country-level. The coefficients with are significant at the 1% level, with are significant at the 5% level, and with are significant at the 10% level.

Yet democracies also invest more in education (Acemoglu et al., 2019), meaning that their populations might be better placed to understand the risks associated with the exponential growth of COVID-19 cases. To also examine this possibility, in column 2 we interact policy stringency with the human capital index from the Penn World Tables. Again, the human capital interaction coefficient is not statistically significant.

Another possible mechanism relates to the capacity of the state to implement its policies. For example, Fukuyama (2020) has argued that countries response to the pandemic has been less shaped by political regime type than by competent government and state capacity. It is certainly possible that democracies generally exhibit higher levels of state capacity and are thus better placed to implement and enforce the lockdown measures taken. To assess this, in column 3 we include an interaction with tax revenue over GDP, which is a widely used measure of fiscal state capacity (e.g. Besley, Persson, 2009, Johnson, Koyama, 2017). To capture bureaucratic state capacity, we also add an interaction with an index of bureaucratic quality from V-Dem in column 4. We note that both variables are not statistically significant.

A further possibility is that the edge of democracy in fostering policy compliance rather depends on its soft infrastructure, such as the provision of more and better information. Put simply, citizens in democracies might be better informed, and thus more aware of the risks associated with the pandemic. To that end, in column 5, we interact policy stringency with a proxy of the quality of information, as measured by the number of people connected to the internet over the total population. Doing so, we do not find any significant impact of internet access.

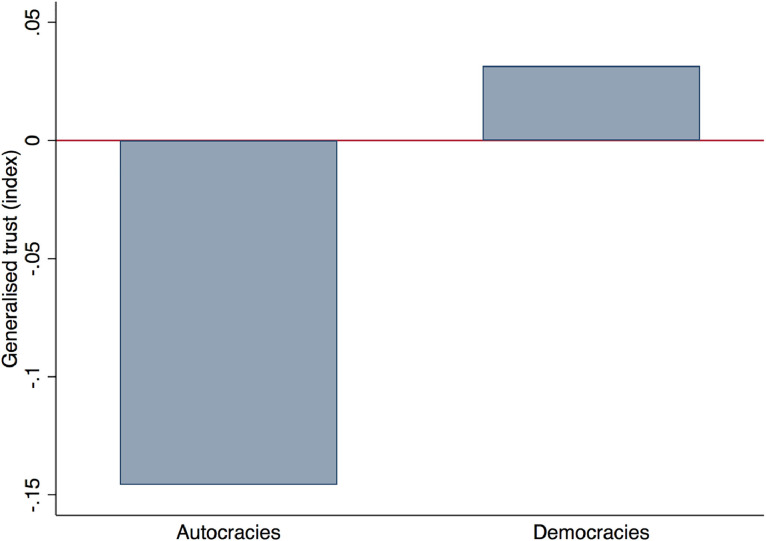

Finally, as noted, social capital is the glue that facilitates cooperation across different social groups, clans, or families, and so permits collective action at the national level, such as mitigating the spread of infectious disease. Following Barrios et al. (2021), we quantify social capital as the incidence of generalised trust across countries, based on data from the widely used World Value Survey (WVS, wave 6).20 In column 6 of Table 6, we estimate model (2) interacting policy stringency with social capital.21 The interaction coefficient is negative and significant, suggesting places with higher levels of social capital saw greater policy compliance. While this does not establish that social capital is the only driver of the relationship between democracy and compliance, it does suggests that the edge of democracy is related to perceptions that support cooperation, rather than the range of other factors explored. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 1, our proxy of social capital is substantially lower in autocracies relative to their democratic counterparts.

Fig. 1.

Social capital in autocratic and democratic regimes.

Notes: This figure presents the average value of social capital measured by generalised trust, for autocratic regimes and other countries. Sources: WVS, World Population Review.

5. Conclusion

A key concern is that the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the decline of democracy. Data published by Freedom House (2020) shows that democracy has been in recession for over a decade, and the rate at which countries have lost civil and political rights has picked up since the 2000s (Diamond, 2020). The challenges democracy faces are well-known. In addition to getting trapped in institutional arrangements that make problem-solving harder (Fukuyama, F. (2014), Fukuyama, 2015), political divisions, checks and balances, and special interest groups can cause gridlock (March, Olsen, 1984, Olsen, 1982), and so limit democratic governments ability to effectively respond to a crisis, like the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, so far, as The New York Times writes, “it is hard to draw up a conclusive balance sheet on the relative disease-fighting abilities of autocracies and democracies” (Schmemann, 2020).

This paper constitutes a first partial assessment. Examining governments policy responses across more than 130 countries, from the beginning to the peak of the first lockdown period, we find that autocracies introduced more stringent lockdowns and relied more on contact tracing.22 At the same time, however, people in democracies were more compliant with the lockdown measures taken. In other words, countries with democratically accountable governments introduced less stringent lockdowns and experienced larger declines in geographic mobility at the same level of policy stringency. Contrary to the popular perception that autocratic countries have been more effective in coping with the pandemic, people in the most consolidated democracies have been more compliant with governments' policy measures aimed at reducing mobility even without implementing draconian restrictions.

Exploring the mechanisms underpinning the relationship between democracy and compliance, we are able to rule out a host of factors, including more generous welfare systems, greater public goods provision, better access to information though the internet, as well as higher levels of state capacity. Consistent with Xue and Koyama (2019) and Xue (2021), who document a causal negative impact of political repression on social capital, we find that democracies exhibit higher levels of social capital on average, which we also note is associated with greater policy compliance. That said, disentangling to what extent this is the result of democratic institutions fostering social capital or vice versa is notoriously hard, not least since culture and institutions co-evolve and are mutually reinforcing (Henrich, 2015, Henrich, Bowles, Gintis, 2010). Efforts to better understand these interactions in the context of policymaking provides a promising line of future inquiry.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Chen, Frey, and Presidente gratefully acknowledge funding from Citi.

Put differently, when the level of social capital is low, people become more dependent on the state to get things done, meaning that the authoritarian model might be more effective in implementing policy.

This is a key implication of the equilibrium identified by Xue and Koyama (2019) and Xue (2021).

Specifically, our dataset covers the period from January 1 to April 30, 2020.

The Google data includes an additional category: “residential”. Unlike other categories measuring the frequency of visits to a place, “residential” measures the length of time spent at home.

See Hale et al. (2020) for more details on variable construction.

For details on the Polity Score, see https://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html

The results, which are available upon request, are qualitatively identical when using the non-normalised variable.

The countries classified as authoritarian are: Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, China, Cuba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Gabon, Hong Kong, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Laos, Libya, Macao, Mauritania, Nicaragua, Oman, Qatar, Russia, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, and Vietnam.

The transparency index is taken from the World Bank’s GovData360 initiative: https://govdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/.

Recall that our democracy variable is normalised to have zero mean and unitary standard deviation in the sample. Cases of infection increase stringency by . Therefore, a doubling of cases increases stringency by 0.0973/0.09197-1 = 0.058 less in the most consolidated democracies (with a score one standard deviation above the average) relative to the average Polity score.

We flag a country as having experience with past epidemics if it experienced more than fifty SARS or MERS cases.

For instance, South Korea was early to implement open public testing, including “drive through” testing for asymptomatic people.

Examples include the United States and France, which did not implement large-scale contact tracing early on during the pandemic.

The variables are taken from the Quality of Government Institute Basic Dataset. Specifically, the welfare system variable captures the extent to which available arrangements compensate for social risk, and the trust for politicians variable simply measures how much people trust politicians (both on a scale 1 to 10).

As discussed in Section 2, mobility indexes are provided for different mobility categories: .

For instance, going to workplaces might be deemed as essential, while retail shopping or visits to parks are not.

To proxy for the severity of the spread of the virus, we experiment with adding the number of COVID-19 deaths over confirmed cases. Results, which are available upon request, are qualitatively identical.

The coefficients in column 3 imply that the drop in mobility for countries with one standard deviation above the average Polity score is: -81.03–10.41 = - 91.44. Therefore, in these countries mobility dropped by 91.44/81.03-1 = 0.128 more.

Our results are consistent if we use alternative democracy measures, such as those provided by Freedom House, or from the V-Dem dataset. However, we note that the latter variables exhibit much less sample variation than the Polity variable used in this paper. As a result, the coefficients are less precisely estimated. The tables are available upon request.

Specifically, the survey question asks: “generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people? Please tell me on a score of 0 to 10, where 0 means you can’t be too careful, and 10 means that most people can be trusted.”

The sample size is reduced because generalised trust is only available for a subset of countries in the World Value Survey.

More stringent policy might also be interpreted as the outcome of an equilibrium in which the lack of social capital and voluntary participation induces citizens to prefer stricter lockdown rules (Xue, & Koyama, Xue).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Acemoglu D., Johnson S., Robinson J.A., Yared P. Income and democracy. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008;98(3):808–842. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu D., Naidu S., Restrepo P., Robinson J.A. Democracy does cause growth. J. Polit. Econ. 2019;127(1):47–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzenman N., Cavalcanti T., Mata D.D. More than words: Leaders’ speech and risky behavior during a pandemic. Available at SSRN 3582908. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Alesina A., Giuliano P. Culture and institutions. J. Econ. Lit. 2015;53(4):898–944. [Google Scholar]

- Algan Y., Cahuc P. Trust, growth, and well-being: new evidence and policy implications. Handbook Econ. Growth. 2014;2:49–120. [Google Scholar]

- Almond G.A., Verba S. Princeton university press; 1963. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield E.C. Free Press; New York: Simon and Schuster: 1958. The Moral Basis of a Backward Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bargain O., Aminjonov U. Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 2020;192:104316. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios J.M., et al. Civic capital and social distancing during the covid-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2021;193:104310. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetto G., Hix S., Mastrorocco N. The rise and fall of social democracy, 1918–2017. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2020;114.3:928–939. [Google Scholar]

- Besley T. State capacity, reciprocity, and the social contract. Econometrica. 2020;88.4:1307–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Besley T., Persson T. The origins of state capacity: property rights, taxation, and politics. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009;99(4):1218–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacini L., Gallo G., Patriarca F. Identifying policy challenges of COVID-19 in hardly reliable data and judging the success of lockdown measures. J. Popul. Econ. 2020;34.1:275–301. doi: 10.1007/s00148-020-00799-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles S., Gintis H. Princeton University Press; 2011. A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Frey C.B., Presidente G. Culture and contagion: individualism and compliance with COVID-19 policy. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2021;190:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2021.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L. Ill winds: saving democracy from russian rage. Chinese Ambit. Am. Complacency. Penguin Books. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama F. Free Press; 1996. Trust: Human Nature and the Reconstitution of Social Order. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama F. Political order and political decay: From the industrial revolution to the globalization of democracy. Macmillan. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama F. Political order and political decay: from the industrial revolution to the globalization of democracy. Macmillan. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama F. The thing that determines a country’s resistance to the coronavirus. The Atlantic. 2020 [Google Scholar]; March 30

- Gorodnichenko Y., Roland G. Culture, institutions and democratization. Public Choice. 2021;187(1):165–195. doi: 10.1007/s11127-020-00811-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiso L., Sapienza P., Zingales L. Long term persistence. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2016;14(6):1401–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez E., Rubli A., Tavares T. Delays in death reports and their implications for tracking the evolution of COVID-191. Covid Econ. 2020:116. [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Webster S., Petherick A., Phillips T., Kira B. Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker, blavatnik school of government. Data use policy: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY standard. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J. In the secret of our success. Princeton University Press; 2015. The secret of our success. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, J. (2020). The WEIRDest people in the world: how the west became psychologically peculiar and particularly prosperous. Penguin UK.

- Freedom House, (2020). Democracy Index. https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores.

- Johnson N.D., Koyama M. States and economic growth: capacity and constraints. Explor. Econ. Hist. 2017;64:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kostelka F. Does democratic consolidation lead to a decline in voter turnout? Global evidence since 1939. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2017;111.4:653–667. [Google Scholar]

- March J., Olsen J.P. The new institutionalism: organizational factors in political life. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1984;78(3):734–749. [Google Scholar]

- Nannicini T., Stella A., Tabellini G., Troiano U. American economic journal: Economic policy. vol. 5. Princeton University Press; 2013. Social capital and political accountability. [Google Scholar]; 222–50.S.

- Olsen M. Yale University Press; 1982. The rise and decline of nations: Economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou E., Siourounis G. Democratisation and growth. Econ. J. 2008;118.532:1520–1551. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. Princeton University Press; 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Nye Jr J.S. Soft power: the means to success in world politics. Public Affairs. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Schmemann, S. (2020). The virus comes for democracy strongmen think they know the cure for COVID-19. Are they right?, New York Times, April 2.

- Tabellini G. The scope of cooperation: values and incentives. Q. J. Econ. 2008;123(3):905–950. [Google Scholar]

- Tocqueville A.D. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2000. Democracy in America. 1835. Trans. Harvey c. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop. [Google Scholar]

- Wälde, K. (2020). How to remove the testing bias in cov-2 statistics. MedRxiv.

- Wright A.L., et al. Poverty and economic dislocation reduce compliance with COVID-19 shelter-in-place protocols. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2020;180:544–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, M. M. (2021). Autocratic rule and social capital: evidence from imperial China. Working paper.

- Xue, M. M., & Koyama, M. (2019). Autocratic rule and social capital: evidence from imperial china. Working paper.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.