Abstract

Background

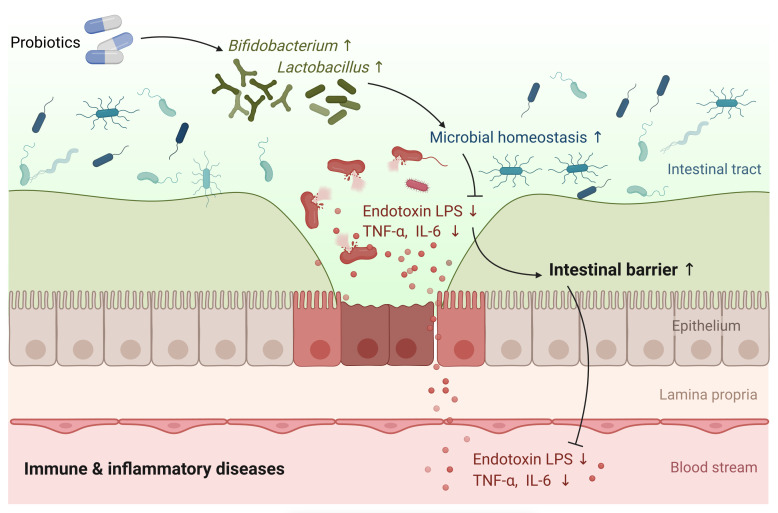

Probiotics play a vital role in treating immune and inflammatory diseases by improving intestinal barrier function; however, a comprehensive evaluation is missing. The present study aimed to explore the impact of probiotics on the intestinal barrier and related immune function, inflammation, and microbiota composition. A systematic review and meta-analyses were conducted.

Methods

Four major databases (PubMed, Science Citation Index Expanded, CENTRAL, and Embase) were thoroughly searched. Weighted mean differences were calculated for continuous outcomes with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), heterogeneity among studies was evaluated utilizing I2 statistic (Chi-Square test), and data were pooled using random effects meta-analyses.

Results

Meta-analysis of data from a total of 26 RCTs (n = 1891) indicated that probiotics significantly improved gut barrier function measured by levels of TER (MD, 5.27, 95% CI, 3.82 to 6.72, P < 0.00001), serum zonulin (SMD, -1.58, 95% CI, -2.49 to -0.66, P = 0.0007), endotoxin (SMD, -3.20, 95% CI, -5.41 to -0.98, P = 0.005), and LPS (SMD, -0.47, 95% CI, -0.85 to -0.09, P = 0.02). Furthermore, probiotic groups demonstrated better efficacy over control groups in reducing inflammatory factors, including CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6. Probiotics can also modulate the gut microbiota structure by boosting the enrichment of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

Conclusion

The present work revealed that probiotics could improve intestinal barrier function, and alleviate inflammation and microbial dysbiosis. Further high-quality RCTs are warranted to achieve a more definitive conclusion.

Clinical trial registration

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=281822, identifier CRD42021281822.

Keywords: intestinal barrier function, randomized controlled trial, immune function, inflammation, probiotics

1. Introduction

Intestinal barrier function is closely related to the pathogenesis of various immune and inflammatory diseases (1–3). The intestinal barrier, including surface mucus, epithelial layer, and immune defense, is a dynamic entity interacting with and responding to a variety of stimuli (2). The physical barrier has epithelial and mucus components tightly linked to different cellular junctions, including desmosomes, adherens junctions, and tight junctions (4). The primary function of the intestinal epithelium is to act as a barrier that limits the interaction between luminal contents, such as gut bacteria, the underlying immune system, and the rest of the body (5). Moreover, the biological barrier mainly comprises the normal intestinal flora and can regulate the intestinal microecological balance (6). A leaky gut occurs due to the perturbation of gut barrier homeostasis with increased epithelial permeability and perhaps microbial dysbiosis, which can lead to the passage of toxins, antigens, and bacteria from the lumen to enter the bloodstream, thus resulting in diverse systemic consequences, including increased inflammation, oxidative stress, and blunted insulin sensitivity (1, 7, 8).

The intestinal microbiota plays an essential role in maintaining gut homeostasis and functionality in the presence of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory microbes. Intestinal commensal microbes promote health, in part, by reinforcing the gut barrier via direct and indirect mechanisms (9). Probiotics are living microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host when given proper amounts and durations (10). Probiotics and intestinal symbionts can modulate the intestinal barrier function of the host through their surface molecules and metabolites (11). Thus, probiotics could restore intestinal health by attenuating inflammation and strengthening the epithelial barrier. Therefore, probiotics may be essential in treating diseases by improving intestinal barrier function.

A prior meta-analysis suggested that supplementation with probiotics can be beneficial in protecting the gut mucosal barrier in patients with colorectal cancer after an operation (12). However, an exhaustive assessment of probiotics regulating intestinal barrier function in multiple disease conditions is still missing. This study aims to comprehensively evaluate the role of probiotics in contributing to intestinal barrier function, and the related immune function, inflammatory status, and gut microbiota composition, thus providing a better understanding of the beneficial effects of probiotic supplementation.

2. Methods

2.1. Study protocol

This systematic review and meta-analysis was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (13), and the PRISMA checklist is available in Supplementary Table S1 . The protocol for the present study has already been registered at PROSPERO (No. CRD42021281822).

2.2. Data source and search strategy

The data source of this review was gained by searching four major biomedical databases: PubMed, Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Embase from inception to February 10, 2022. Keywords in the search strategy included probiotics, gut barrier, intestinal barrier, leaky gut, random clinical trials, etc. No language restrictions or limitations of the published year were imposed. The detailed search strategies were provided in Supplementary Materials ( Tables S2–S5 ). All the search results from four different databases were stored in EndNote Library 20 for manageable convenience.

2.3. Study selection criteria

All articles are irrespective of population. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts and subsequently assessed the eligibility of the full texts of identified studies to select potentially eligible studies. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer if there were still discrepancies after the discussion between the two reviewers.

The inclusion criteria for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that needed to be met were as follows: the intervention group should add single- or multiple-strain probiotics, and outcomes were at least one parameter of intestinal barrier function assessed. We excluded RCTs that interventions were not probiotics or whose outcomes were not relevant to intestinal permeability. Review articles, meta-analysis articles, and animal studies were omitted. However, the references of these publications were screened for potentially includable studies.

2.4. Data extraction

Vital data information about each study, including the author’s name, published year, country, type of study, characteristics of the study population (sex, age, body weight, etc.), experimental design, duration of intervention, sample size; and outcomes of the intestinal barrier function, gut microbiota, inflammatory indicators, and immune functions were extracted from each article that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Two reviewers carried out this work independently and resolved disagreements by consensus.

2.5. Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers conducted the risk of bias assessment independently, and different opinions were sent to another senior author to be solved. We applied the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias through the software Review Manager (RevMan 5.4) to evaluate the quality of the studies included in our system review (14). There are six evaluation items in different aspects, including the selection bias of random sequence generation as well as allocation concealment, the performance bias of blinding of participants and personnel, the detection bias of blinding of outcome assessment, the attrition bias of incomplete outcome data, the reporting bias of selective reporting and other bias, which were judged as the conclusion of low, high, or unclear risk.

2.6. Data synthesis and analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using the Review Manager software (RevMan 5.4) (15). We calculated weighted mean differences for continuous outcomes with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In the data analysis of included studies, a mean difference (MD) model in RevMan will be applied if the data units are uniform; otherwise, a standard mean difference (SMD) model will be employed. If more than one time point of outcome during the treatment were reported, the data from the last time point would be extracted for pooled analysis. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated utilizing I 2 statistic (Chi-Square test). A fixed-effect model was applied for the analysis of homogenous data (I 2 < 50%); alternatively, a random-effect model will be applied for heterogeneous data (16). Funnel plot asymmetry was examined to evaluate the publication bias. Subgroup analyses were performed based on country, population characteristics, age, study design, treatment duration, etc., to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among each result indicator.

All data pooling in the meta-analysis was in the form of mean ± standard deviation (SD). When the original data were reported as median and range (or interquartile range), we estimated the mean and SD using an online calculator provided by Luo et al. (17). Engauge Digitizer software (version 11.1) was applied to extract data from the studies which provide data in figures other than numerically.

2.7. Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analysis was conducted based on the main possible contributing factors that may cause heterogeneity, including country, population characteristics, and duration of treatment.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

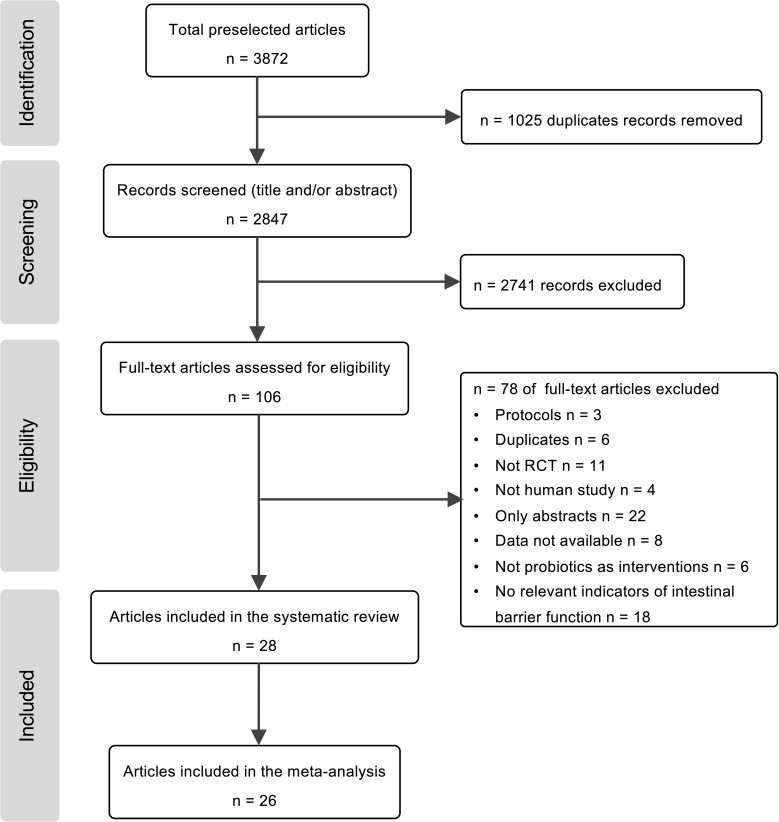

A total of 3872 potentially relevant studies were retrieved after a combined search from four databases, and 2847 remaindered to go through the articles’ titles and abstracts after excluding the duplicates. The number of articles was reduced to 106 for further full-text screening, 28 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis, and 26 RCTs were included in the meta-analysis ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection progress for the systematic review and meta-analyses.

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the 28 included studies were all RCTs ( Table 1 ). A total of 1891 randomized participants divided into probiotic intervention groups (n = 955) and control (n = 936) groups were included in this systematic review. Across the included studies, the study population mainly combined two kinds of people, patients and athletes. The characteristics of patients are mainly related to hepatic diseases (23, 24), acute pancreatitis (19, 31, 33), gastrointestinal diseases (20, 21, 27–29, 35, 36, 42–45), metabolic disorders (26, 39), and acute diseases (18, 30, 32, 41). Apart from those kinds of patients, there were also RCTs on migraine (22), early sepsis (38), and psychological stress (37). Studies of probiotics on healthy subjects, e.g., endurance-trained men (25), male runners (34), and division I male baseball athletes (40) are also included. All included articles were published between 2005 and 2021, and six were published in the last three years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included randomized controlled trials.

| Study | Country | Design | Population characteristics | Age | Control | Probiotics | Study duration | n | Intestinal barrier function | Gut microbiota | Other indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | Canada | Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial | Critically ill patients | Control: 64.9 ± 16.9 Probiotics: 60.4 ± 17.9 |

Placebo | VSL#3: Lactobacillus (L. casei, L. plantarum, L. acidophilus, and L. delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus), Bifidobacterium (B. longum, B. breve, and B. infantis) and Streptococcus salivarius subsp. Thermophilus (2 sachets twice daily) | 7 days | Control: 9 Intervention: 10 |

L/M | — | CRP, IgA, IgG |

| 19 | Netherlands | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial | Patients with a first episode of predicted severe acute pancreatitis | 60.5 ± 16.0 | Placebo | Ecologic 641: a mixture of 6 lactobacillus, lactococcus, or bifidobacteriae | 7 days | Control: 144 Intervention: 152 |

IFABP, PEGs, NOx | — | — |

| 20 | Italy | Crossover randomized double-blind controlled trial |

Patients with irritable bowel syndrome | 48 ± 11 | Placebo (maltodextrins, corn starch, silicon dioxide) | LBB: Bifidobacterium longum BB536 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 with vitamin B6 (1 sachet pack daily) | 60 days | Control: 25 Intervention: 25 |

L/M, sucralose recovery | — | — |

| 21 | China | Randomized, parallel-group, controlled trial | Patients with colorectal cancer | Control: 59.8 ± 18.7 Probiotics: 60.3 ± 17.2 |

Placebo | Combined Clostridium Butyricum and Bifidobacterium Capsules,Live (capsule: 3 capsules thrice daily) | 12 days | Control: 35 Intervention: 35 |

TER, Mannitol permeability | Bifidobacteria, Lactobacilli, Enterobacterium |

— |

| 22 | Netherlands | Randomized placebo-controlled study | Patients with migraine | Control: 38 (18–70) Probiotics: 42 (18–69) |

Placebo (2g of the carrier of the probiotic product; maize starch and maltodextrin powder) |

Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, B. lactis W52, Lactobacillus acidophilus W37, Lactob. brevis W63, Lactob. casei W56, Lactob. salivarius W24, Lactococcus lactis W19 and Lactoc. lactis W58 (2g sachets once daily) | 12 weeks | Control: 29 Intervention: 31 |

L/M, Zonulin in feces and serum | — | CRP, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α |

| 23 | Austria | Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study | Patients with cirrhosis | Control: 56 (50; 63) Probiotics: 60 (54; 64) |

Placebo | Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, Bifidobacterium lactis W52, Lactobacillus acidophilus W37, Lactobacillus brevis W63, Lactobacillus casei W56, Lactobacillus salivarius W24, Lactococcus lactis W19 and Lactococcus lactis W58 (6g daily) | 6 months | Control: 36 Intervention: 44 |

L/M, DAO, ET Zonulin in fecal, sucralose recovery | — | CRP |

| 24 | Republic of Korea | Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study | Patients with chronic liver disease | Control: 53.3 ± 9.8 Probiotics: 54.4 ± 8.4 |

Placebo | Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Streptococcus thermophilus (capsule: twice daily) | 4 weeks | Control: 25 Intervention: 25 |

L/M | Bifido group, Lacto group |

— |

| 25 | Austria | Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial | Endurance trained men | Control: 38.2 ± 4.4 Probiotics: 37.6 ± 4.7 |

Placebo (a matrix cornstarch, maltodextrin, vegetable protein) | Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, Bifidobacterium lactis W51, Enterococcus faecium W54, Lactobacillus acidophilus W22, Lactobacillus brevis W63, and Lactococcus lactis W58 (4g daily) | 14 weeks | Control: 12 Intervention: 11 |

Zonulin in fecal | — | IL-6, TNF-α |

| 26 | Austria | An open label, randomized pilot study | Patients with metabolic syndrome | Control: 54.5 ± 8.9 Probiotics: 51.5 ± 11.4 |

Standard treatment | YAKULT light: L. casei Shirota (liquid: 3 bottles of 65 ml daily) | 3 months | Control: 15 Intervention: 13 |

Recovery of saccharose, L/M, DAO | — | — |

| 27 | China | Double-center and double-blind randomized clinical trial |

Patients with colorectal liver metastases | Control: 60.16 ± 16.20 Probiotics: 65.62 ± 18.18 |

Placebo (maltodextrin) | Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus-11 and Bifidobacterium longum-88 (capsules: 2g daily) | 16 days | Control: 58 Intervention: 59 |

ET, Zonulin in serum | — | — |

| 28 | China | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective study | Patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery |

Control: 65.7 ± 9.9 Probiotics: 65.3 ± 11.0 |

Placebo (maltodextrin) | Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus-11 and Bifidobacterium longum-88 (capsules: 2g daily) | 16 days | Control: 50 Intervention: 50 |

L/M, TER, I-FABP | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Enterobacteriaceae | — |

| 29 | China | Double-center and double-blind randomized clinical trial |

Patients with colorectal cancer | Control: 62.28 ± 12.41 Probiotics: 66.06 ± 11.02 |

Placebo (maltodextrin) | Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus-11 and Bifidobacterium longum-88 (capsules: 2g daily) | 16 days | Control: 75 Intervention: 75 |

L/M, serum zonulin, TER | — | — |

| 30 | UK | A prospective randomized trial | Critically ill patients. | Control; 71 (28-87) Probiotics: 71 (28-90) |

Conventional therapy | ProViva: L. plantarum 299v (liquid: 500 ml daily) | 15 days | Control: 51 Intervention: 52 |

L/R | — | IL-6 |

| 31 | China | Prospective, randomized, single-blinded, parallel design clinical trial | Patients with acute pancreatitis | Control: 58.4 ± 19.1 Probiotics: 54.3 ± 13.1 |

Parenteral nutrition | Lactobacillus plantarum (liquid: 100ml daily through the nasojejunal tube) | 1 week | Control: 38 Intervention: 36 |

L/R | Bifidobacteria, Lactobacteria, Enterococci | CRP |

| 32 | Iran | Randomized, double−blind, placebo−controlled trial |

Critically ill patients | Control: 35.60 ± 5.03 Probiotics: 33.60 ± 5.50 |

Placebo | VSL#3: Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp., Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium breve, and Bifidobacterium infantis and Streptococcus salivarius subsp. Thermophilus. (2 sachets daily) |

7 days | Control: 20 Intervention: 20 |

— | — | IL−6 |

| 33 | India | Randomized, double−blind, placebo−controlled trial |

Patients with acute pancreatitis | Control: 40.19 ± 17.43 Probiotics: 41 ± 20.72 |

Placebo | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium longus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Bifidobacterium infantalis (4 sachets daily) | 7 days | Control: 26 Intervention: 24 |

L/M | — | hsCRP, IgG, IgM |

| 34 | Australia | Double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over trial | Male runners | 27 ± 2 | Placebo (skim milk powder) |

Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, L. casei, L. plantarum, L. fermentum, Bifidobacterium lactis, B. breve, B. bifidum and Streptococcus thermophilus (capsule: 1 capsule daily) | 4 weeks | Control: 10 Intervention: 10 |

L/R, LPS | — | IgM, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α |

| 35 | India | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Children with gastroenteritis | 6 months -5 years | Placebo | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (1 capsule given once daily in boiled and cooled milk) | 4 weeks | Control: 59 Intervention: 65 |

L/M | — | — |

| 36 | Canada | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | Patients with untreated celiac disease | Control; 40 (20-71) Probiotics: 46 (29-62) |

Placebo (rice flour, dehydrated potato powder, cellulose powder, and hydroxypropyl-methylcellulose) |

Bifidobacterium infantis natren life start strain super strain (capsule: 2 capsules thrice daily) |

3 weeks | Control: 10 Intervention: 12 |

L/M | — | IL-6 |

| 37 | Italy | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial | Healthy adults who self-reported psychological stress | 20-35 | Placebo (liquid mixture) |

Lactoflorene® Plus: Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5®, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, BB-12®, Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei, L. CASEI431®, Bacillus coagulans BC513, zinc and B vitamins (niacin, B1, B2, B5, B6, B12 and folic acid) (liquid: two 10ml bottles daily) | 45 days | Control: 25 Intervention: 25 |

— | — | IgA, IL-10, TNF-α |

| 38 | Austria | Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled pilot study | Patients with early sepsis | 54 (47; 60) | Placebo | Lactobacillus plantarum W1, Lactobacillus paracasei W20, Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, Lactobacillus salivarius W24, Lactobacillus acidophilus W37, Bifidobacterium lactis W51, Enterococcus faecium W54, Lactobacillus acidophilus W55, Lactobacillus plantarum W62, Lactobacillus rhamnosus W71 (5g twice daily) | 28 days | Control: 4 Intervention: 5 |

DAO, ET, Zonulin in stool |

— | — |

| 39 | Thailand | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus | Control: 61.78 ± 7.73 Probiotics: 63.50 ± 5.94 |

Placebo (corn starch) |

L. paracasei HII01 (50 × 109 CFU/day) | 12 weeks | Control: 18 Intervention: 18 |

ZO-1, LPS | — | hsCRP, IgA, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α |

| 40 | USA | Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study | Division I male baseball athletes | 20.1 ± 1.5 | Placebo (maltodextrin) | Bacillus subtilis DE111 (capsule: 1.2 billion CFU/capsule) | 12 weeks | Control: 12 Intervention: 13 |

Zonulin in serum | — | IL-10, TNF-α |

| 41 | China | Single-blind, randomized controlled trial | Critically ill patients. | Control: 81 (61; 95) Probiotics: 81 (70; 96) |

Placebo | Clostridium butyricum (tablet: 1 sachet thrice daily) | 14 days | Control: 33 Intervention: 27 |

DAO, LPS | — | IL-10, TNF-α |

| 42 | Netherlands | Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study | Patients with ulcerative colitis | Control: 51.1 ± 11.9 Probiotics: 51.8 ± 13.3 |

Placebo (maize starch and maltodextrins) |

Ecologic® 825: Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, Bifidobacterium lactis W51, Bifidobacterium lactis W52, Lactobacillus acidophilus W22, Lactobacillus casei W56, Lactobacillus paracasei W20, Lactobacillus plantarum W62, Lactobacillus salivarius W24, and Lactococcus lactis W19 (2 sachets daily of 3g) | 12 weeks | Control: 12 Intervention: 13 |

L/R, S/E, Zonulin in serum and faecal | — | IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α |

| 43 | China | Randomized, parallel-group, controlled trial | Patients undergo colonic surgery | 67.3 (37–82) | Preoperative bowel preparation methods | Lactobacillus acidophilus LA11 (granule; 2g daily) | ≥5 days | Control: 30 Intervention: 30 |

— | — | IgA |

| 44 | China | Single-center prospective randomized control study | Patients with colorectal cancer | Control: 61.5 (46.0–82.0) Probiotics: 67.5 (45.0–87.0) |

Placebo (maltodextrins) | B longum, L acidophilus and Enterococcus faecalis (capsule: 3 capsules thrice daily) | 3 days | Control: 30 Intervention: 30 |

D-LA, ET | — | CRP, IgA, IgG, IgM, IL-6 |

| 45 | China | Randomized, parallel-group, controlled trial | Patients with diarrhea secondary to leukemia chemotherapy | Control: 9.26 ± 1.84 Probiotics: 9.17 ± 1.92 |

Routine symptomatic support | Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Enterococcus faecalis (capsule: 1 capsule twice daily) | 2 weeks | Control: 45 Intervention: 45 |

DAO, D-LA, ET | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, Enterobacteriaceae | IL-6, TNF-α |

"__" means not mentioned.

In most included studies, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus were added to evaluate the efficacy of probiotics compared to control groups. Probiotics were administered in different dosage forms, including capsules, tablets, and liquids. The duration of the intervention varied from 3 days to 6 months.

Outcomes were mainly measured in four aspects: intestinal barrier function indicators, inflammatory factors, immune function indicators, and gut microbiota structures. Evaluation of intestinal barrier function has different indicators, including the levels of diamine oxidase (DAO), D-lactic acid (D-LA), ratios of lactulose to mannitol (L/M), and lactulose to rhamnose (L/R), endotoxin (ET), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), serum and fecal zonulin, intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (I-FABP), and transepithelial resistance (TER). Inflammatory factors of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 10 (IL-10), C-reactive protein (CPR), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were measured to assess the anti-inflammatory function of probiotics supplementary. Moreover, Immunoglobulin A (IgA), Immunoglobulin G (IgG), and Immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels were measured to assess whether probiotics could improve immune function.

3.3. Quality of included studies

All the included studies were assessed for quality in different aspects using the Cochrane Collaboration tool ( Figures S1 ; S2 ). Among the 28 RCTs, random sequence generation in 19 studies tended to be a low-risk bias, and nine did not report the method of random sequence generation. In allocation concealment, 16 studies showed low bias, and 12 did not provide information on allocation concealment. Eleven studies provided no information on the blinding of participants and personnel, and 24 did not report the blinding of outcome assessment. Ten studies did not provide details on incomplete outcome data, and 26 RCTs did not provide enough information to evaluate selective reporting. The most common risks of other biases in these studies were assessment biases and possibly a lack of adequate control of various factors, such as doses of probiotics, lengths of treatment, and methods of assessments.

3.4. Effects of probiotics on intestinal barrier function

Different kinds of methods were applied to assess the intestinal barrier function. In the 28 studies, a total of 19 test methods were used; seven assessed intestinal permeability, six assessed intestinal integrity, one related to bacterial translocation, three related to harmful factors, and two other indicators ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Methods applied to assess the intestinal barrier function and the efficacy of probiotics.

| Methods | Number | Studies | Participants | Mean difference (95% CI) |

P - value | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L/M | 8 | 18, 22, 26, 28, 29, 33, 35, 36 | 517 | -0.02 [-0.03, 0.00] | P = 0.06 | I2 = 87% |

| Fecal Zonulin | 5 | 22, 23, 25, 38, 42 | 190 | -1.63 [-14.06, 10.81] | P = 0.80 | I2 = 50% |

| Serum Zonulin | 5 | 22, 27, 29, 40, 42 | 385 | -1.58 [-2.49, -0.66] | P = 0.0007 | I2 = 92% |

| ET | 4 | 27, 38, 44, 45 | 219 | -3.20 [-5.41, -0.98] | P = 0.005 | I2 = 97% |

| DAO | 5 | 23, 26, 38, 41, 45 | 268 | -0.31 [-1.03, 0.40] | P = 0.39 | I2 = 86% |

| L/R | 4 | 30, 31, 34, 42 | 143 | -0.04 [-0.13, 0.04] | P = 0.33 | I2 = 97% |

| TER | 3 | 21, 28, 29 | 170 | 5.27 [3.82, 6.72] | P < 0.00001 | I2 = 0% |

| LPS | 3 | 34, 39, 41 | 113 | -0.47 [-0.85, -0.09] | P = 0.02 | I2 = 48% |

| D-LA | 2 | 44, 45 | 150 | -1.95 [-4.57, 0.68] | P = 0.15 | I2 = 98% |

| I-FABP | 2 | 19, 28 | 187 | 67.93 [3.43, 132.43] | P = 0.04 | I2 = 72% |

| Fecal calprotectin | 2 | 23, 38 | 89 | 31.78 [-138.88, 202.45] | P = 0.72 | I2 = 65% |

| LBP | 2 | 23, 38 | 89 | 0.10 [-0.31, 0.52] | P = 0.63 | I2 = 0% |

| HRP | 2 | 28, 29 | 250 | -0.54 [-0.60, -0.49] | P < 0.00001 | I2 = 0% |

| S/E | 1 | 42 | 25 | 0.01 [0.00, 0.02] | P = 0.01 | Not applicable |

| Mannitol permeability | 1 | 21 | 60 | -0.74 [-0.87, -0.61] | P < 0.00001 | Not applicable |

| PEGs | 1 | 19 | 67 | 0.11 [-0.95, 1.17] | P = 0.84 | Not applicable |

| Saccharose recovery | 1 | 26 | 28 | -0.30 [-0.56, -0.04] | P = 0.03 | Not applicable |

| ZO-1 | 1 | 39 | 36 | -0.29 [-0.75, 0.17] | P = 0.22 | Not applicable |

| NO | 1 | 19 | 94 | 214.06 [56.03, 372.09] | P = 0.008 | Not applicable |

L/M, lactulose/mannitol; L/R, lactulose/rhamnose; S/E, sucralose/erythritol; PEGs, polyethylene glycols; D-LA, D-lactic acid; TER, transepithelial electrical resistance; ZO-1, zonula occluden-1; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; NO, nitric oxide; ET, endotoxin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LBP, lipopolysaccharide binding protein; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; DAO, diamine oxidase.

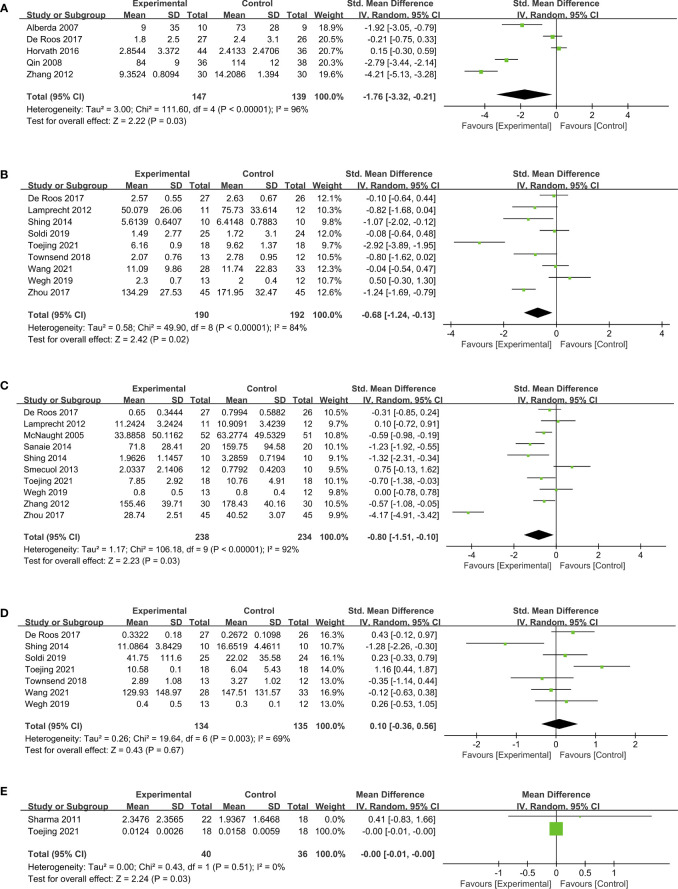

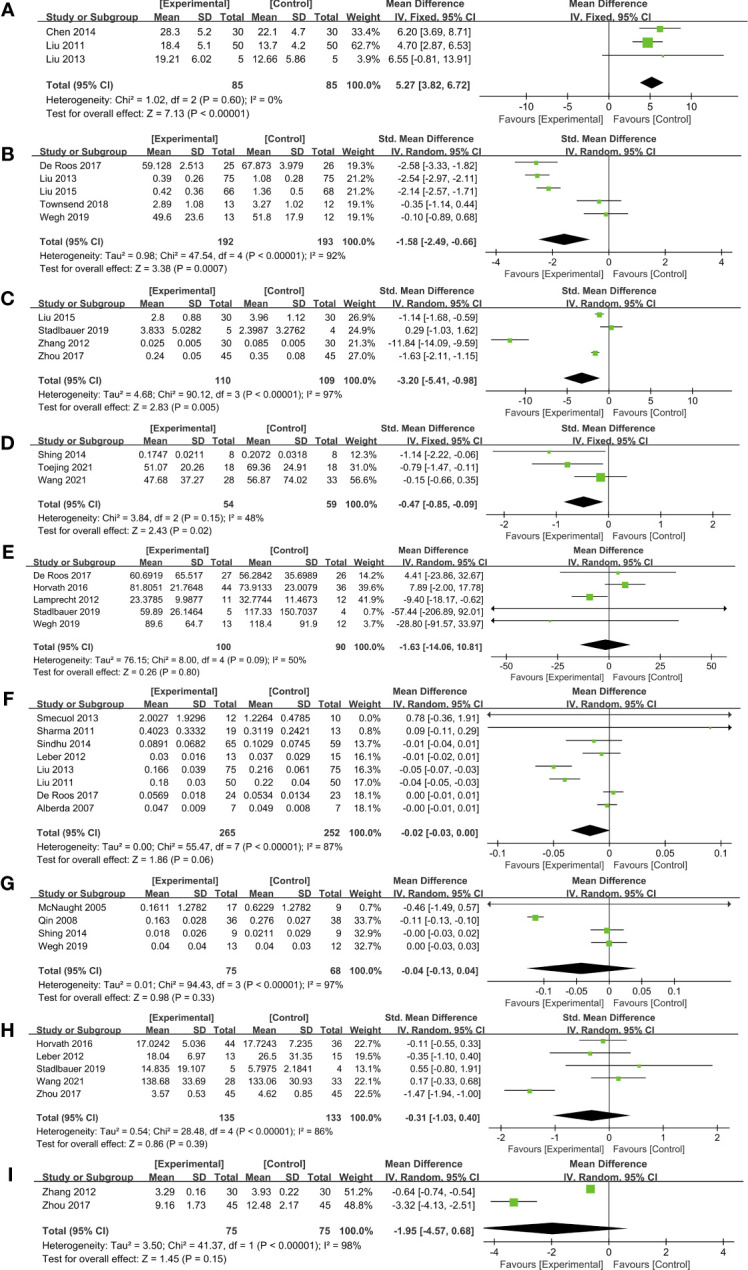

A meta-analysis of intestinal barrier function was mainly measured in the TER, serum and fecal zonulin levels, ET, LPS, L/M, L/R, DAO, and D-LA. Three RCTs (21, 28, 29) assessed TER to evaluate the ameliorating effect of probiotics on intestinal barrier function. As indicated by the pooling data ( Figure 2A ), probiotics significantly enhanced the TER compared with placebo (MD, 5.27, 95% CI, 3.82 to 6.72, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of the effect of probiotics on intestinal barrier function. (A) TER, (B) Serum zonulin, (C) ET, (D) LPS, (E) Fecal zonulin, (F) L/M, (G) L/R, (H) DAO, (I) D-LA. DAO, diamine oxidase; D-LA, D-lactic acid; ET, endotoxin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; L/M, lactulose to mannitol; L/R, lactulose to rhamnose.

Measured by serum zonulin concentrations, pooling data from five studies (22, 27, 29, 40, 42) which included 385 subjects demonstrating a significant improvement in probiotic intervention on gut barrier function compared to placebo (SMD, -1.58, 95% CI, -2.49 to -0.66, P = 0.0007; Figure 2B ). Subgroup analysis was conducted based on the country, population characteristics, and duration of treatment ( Table 3 ). Among these five RCTs that measured serum zonulin levels, one study (40) included athletes, and the other four (22, 27, 29, 42) were patients. As revealed by the subgroup analysis, RCTs of patients suggested a remarkable decrease in serum zonulin level (SMD, -1.87, 95% CI, -2.77 to -0.98, P < 0.0001), while the data from athletes did not exhibit significant changes. In addition to subject type, the intervention duration may also affect the efficacy of probiotics. As revealed in the subgroup analysis ( Table 3 ), three RCTs (22, 40, 42) with treatment more extended than four weeks did not achieve significant efficacy. However, two studies (27, 29) involving 284 patients administered probiotics for less than four weeks have notably enhanced the intestinal barrier function assessed by serum zonulin levels (SMD, -2.34, 95% CI, -2.64 to -2.03, P < 0.00001) with low statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 40%).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of serum zonulin.

| Subgroup by | Studies | Participants | SMD (95% CI) | I2 | P | P for heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | China | 2 | 284 | -2.34[-2.64, -2.03] | 40% | <0.00001 | 0.20 |

| Netherlands | 2 | 76 | -1.34[-3.77, 1.08] | 95% | 0.28 | <0.00001 | |

| USA | 1 | 5 | -0.35[-1.14, 0.44] | NA | 0.39 | NA | |

| Population characteristics | Athletes | 1 | 25 | -0.35[-1.14, 0.44] | NA | 0.39 | NA |

| Patients | 4 | 360 | -1.87[-2.77, -0.98] | 90% | <0.0001 | <0.00001 | |

| Duration of treatment | < 4 weeks | 2 | 284 | -2.34[-2.64, -2.03] | 40% | <0.00001 | 0.20 |

| ≥4 weeks | 3 | 101 | -1.01[-2.58, 0.55] | 92% | 0.20 | <0.00001 | |

Five RCTs (22, 23, 25, 38, 42) measured fecal zonulin levels; however, no significant difference was observed between probiotics and placebo groups ( Figure 2E ). A subgroup analysis based on the duration of treatment revealed an interesting phenomenon ( Table 4 ). Among the five studies, four interventions involving 110 subjects lasted less than six weeks. Pooling data from these four RCTs (22, 23, 25, 42) demonstrated a remarkable reduction of fecal zonulin levels after probiotics supplementation (MD, -8.69, 95% CI, -16.99 to -0.40, P = 0.04, I2 = 0%). This outcome is similar to serum zonulin, implying that the duration of probiotic interventions needs to be a concern during clinical application.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of fecal zonulin.

| Subgroup by | Studies | Participants | MD (95% CI) | I2 | P | P for heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Austria | 3 | 112 | -1.57[-17.76, 14.62] | 72% | 0.85 | 0.03 |

| Netherlands | 2 | 78 | -1.19[-26.96, 24.58] | 0% | 0.93 | 0.34 | |

| Population characteristics | Endurance trained men | 1 | 23 | -9.40 [-18.17, -0.62] | NA | 0.04 | NA |

| Patients | 4 | 167 | 6.48 [-2.74, 15.70] | 0% | 0.17 | 0.57 | |

| Duration of treatment | < 6 months | 4 | 110 | -8.69 [-16.99, -0.40] | 0% | 0.04 | 0.65 |

| ≥6 months | 1 | 80 | 7.89 [-2.00, 17.78] | NA | 0.12 | NA | |

Endotoxin and LPS can increase gut permeability and thus cause a leaky gut. Probiotics potently decreased the level of endotoxin (SMD, -3.20, 95% CI, -5.41 to -0.98, P = 0.005, I2 = 97%) in four studies (27, 38, 44, 45) ( Figure 2C ). Furthermore, compared with placebo, probiotics in three RCTs (34, 39, 41) showed a significant reduction in LPS levels (SMD, -0.47, 95% CI, -0.85 to -0.09, P = 0.02) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 48%; Figure 2D ).

Of 26 studies included in the data pooling, eight studies (18, 22, 26, 28, 29, 33, 35, 36) composed of 517 subjects reported L/M levels. The forest plot showed no significant L/M level reduction in probiotics groups compared to control groups (MD, -0.02, 95% CI, -0.03 to 0.00, P = 0.06) with high heterogeneity I2 = 87% ( Figure 2F ). However, according to a subgroup analysis conducted based on population characteristics ( Table 5 ), patients with gastrointestinal diseases in four RCTs (28, 29, 35, 36) displayed a significant reduction of L/M levels (MD, -0.04, 95% CI, -0.06 to 0.02, P = 0.0001, I2 = 60%), indicating that probiotics may have varying power in improving intestinal permeability of patients with different diseases. Similar to L/M, data on L/R from four studies (30, 31, 34, 42) fail to achieve an effective improvement after probiotic intervention (MD, -0.04, 95% CI, -0.13 to 0.04, P = 0.33; Figure 2G ).

Table 5.

Subgroup analysis of L/M.

| Subgroup by | Studies | Participants | MD (95% CI) | I2 | P | P for heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Austria | 1 | 28 | -0.01[-0.02, 0.01] | NA | 0.42 | NA |

| Canada | 2 | 36 | -0.00 [-0.01, 0.01] | 45% | 0.67 | 0.18 | |

| China | 2 | 250 | -0.04[-0.05, -0.03] | 0% | <0.00001 | 0.36 | |

| India | 2 | 156 | -0.01 [-0.04, 0.01] | 3% | 0.34 | 0.31 | |

| Netherlands | 1 | 47 | 0.00 [-0.01, 0.01] | NA | 0.45 | NA | |

| Population characteristics | Critically ill patients | 1 | 14 | -0.00 [-0.01, 0.01] | NA | 0.66 | NA |

| Patients with migraine | 1 | 47 | 0.00 [-0.01, 0.01] | NA | 0.45 | NA | |

| Patients with metabolic syndrome | 1 | 28 | -0.01 [-0.02, 0.01] | NA | 0.42 | NA | |

| Patients with acute pancreatitis | 1 | 32 | 0.09 [-0.11, 0.29] | NA | 0.37 | NA | |

| Patients with gastrointestinal diseases | 4 | 396 | -0.04[-0.06, -0.02] | 60% | 0.0001 | 0.06 | |

| Age | <18 | 1 | 124 | -0.01 [-0.04, 0.01] | NA | 0.28 | NA |

| ≥18 | 7 | 393 | -0.02 [-0.04, 0.00] | 89% | 0.09 | <0.00001 | |

| Duration of treatment | < 2 weeks | 2 | 46 | 0.00 [-0.01, 0.01] | 0% | 0.69 | 0.36 |

| ≥2 weeks | 6 | 471 | -0.02 [-0.04, 0.00] | 90% | 0.07 | <0.00001 | |

Five studies (23, 26, 38, 41, 45) reported DAO (SMD, -0.31, 95% CI, -1.03 to 0.40, P=0.39; Figure 2H ; Table 6 ) and two studies (44, 45) tested D-LA (MD, -1.95, 95% CI, -4.57 to 0.68, P = 0.15; Figure 2I ), however, no significant changes have been observed.

Table 6.

Subgroup analysis of DAO.

| Subgroup by | Studies | Participants | SMD (95% CI) | I2 | P | P for heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Austria | 3 | 117 | -0.12[-0.49, 0.24] | 0% | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| China | 2 | 151 | -0.65 [-2.26, 0.96] | 95% | 0.43 | <0.00001 | |

| Age | <18 | 1 | 90 | -1.47[-1.94, -1.00] | NA | <0.00001 | NA |

| ≥18 | 4 | 178 | -0.02 [-0.32, 0.28] | 0% | 0.89 | 0.54 | |

| Design | Placebo | 3 | 150 | 0.04 [-0.28, 0.36] | 0% | 0.80 | 0.53 |

| Conventional treatment | 2 | 118 | -0.95 [-2.04, 0.15] | 84% | 0.09 | 0.01 | |

| Duration of treatment | < 2 weeks | 2 | 151 | -0.65 [-2.26, 0.96] | 95% | 0.43 | <0.00001 |

| ≥2 weeks | 3 | 117 | -0.12 [-0.49, 0.24] | 0% | 0.52 | 0.52 | |

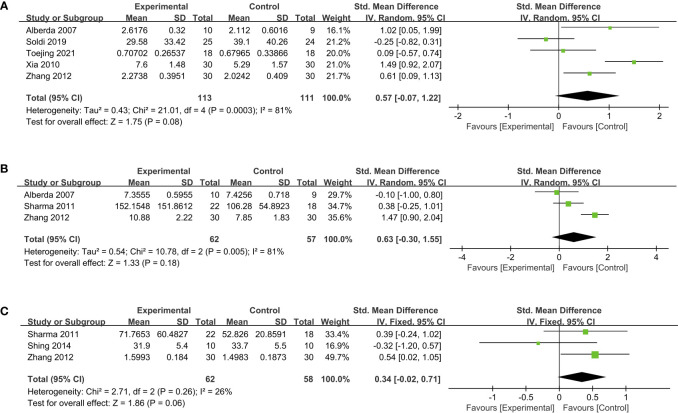

3.5. Effects of probiotics on inflammation

The evaluation of probiotics on inflammation was presented by the levels of CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and hsCRP. The CRP level was measured in five RCTs (18, 22, 23, 31, 44) in 286 patients. Probiotics exhibited dramatically better efficacy over placebo in reducing CRP levels and thus exerting anti-inflammatory activities (SMD, -1.76; 95% CI, -3.32 to -0.21; P = 0.03; Figure 3A ). Subgroup analysis based on the duration of treatment indicated that three studies (18, 31, 44) involving 153 subjects with probiotic intervention less than three months had an even greater reduction of CRP (SMD, -2.99; 95% CI, -4.17 to -1.82; P < 0.00001). In contrast, two studies (22, 23) treated with probiotics for more than three months displayed no significant change in CRP levels ( Table S6 ). TNF-α levels were revealed by pooled data of nine studies (22, 25, 34, 37, 39–42, 45) involving 382 people, showed a decreasing change in probiotic groups compared to control groups (SMD, -0.68; 95% CI, -1.24 to -0.13; P = 0.02; Figure 3B ). Further detailed subgroup analysis is presented in Table S7 .

Figure 3.

Forest plots of overall pooled data on the effect of probiotics on inflammation. (A) CRP, (B) TNF-α, (C) IL-6, (D) IL-10, (E) hsCRP. CRP, C-reactive protein; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; IL-10, interleukin 10; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Ten RCTs (22, 25, 30, 32, 34, 36, 39, 42, 44, 45) involving 472 people were pooled to examine the effect of probiotics on IL-6 levels. As indicated in the forest plot ( Figure 3C ), consumption of probiotics induced decreased IL-6 levels (SMD, -0.80; 95% CI, -1.51 to -0.10; P = 0.03) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 92%). We performed subgroup analyses from various aspects, including countries, population characteristics, age of research subjects, study design, and duration of treatment ( Table S8 ). It is worth noting that eight studies (22, 25, 32, 34, 36, 39, 42, 44) applied placebo as control groups had a greater reduction of IL-6 levels than that of conventional treatment (SMD, -0.42; 95% CI, -0.84 to -0.01; P = 0.05). In addition, supplementing probiotics for less than three months in six studies (30, 32, 34, 36, 44, 45) had more strength in reducing IL-6 levels compared to those for more than three months (SMD, -1.19; 95% CI, -2.31 to -0.07; P = 0.04). However, the probiotic intervention failed to achieve any significant changes in levels of IL-10 ( Figure 3D ; Table S9 ) and hsCRP ( Figure 3E ).

3.6. Effects of probiotics on immune function

The pooled data to evaluate the impact of probiotics on immune function were presented by IgA, IgG, and IgM levels. Compared to placebo groups, supplementing probiotics in five studies (18, 37, 39, 43, 44) did not demonstrate any significant elevation of IgA level (SMD, 0.57; 95% CI, -0.07 to 1.22; P = 0.08; Figure 4A ). In addition, according to meta-analysis, probiotics also failed to effectively improve the levels of IgG (SMD, 0.63; 95% CI, -0.30 to 1.55; P = 0.18; Figure 4B ) and IgM (SMD, 0.34; 95% CI, -0.02 to 0.71; P = 0.06; Figure 4C ) (18, 33, 34, 44).

Figure 4.

Forest plots of the effect of probiotics on immunoglobulin levels. (A) IgA, (B) IgG, (C) IgM. IgA, Immunoglobulin A; IgG, Immunoglobulin G, IgM, Immunoglobulin M.

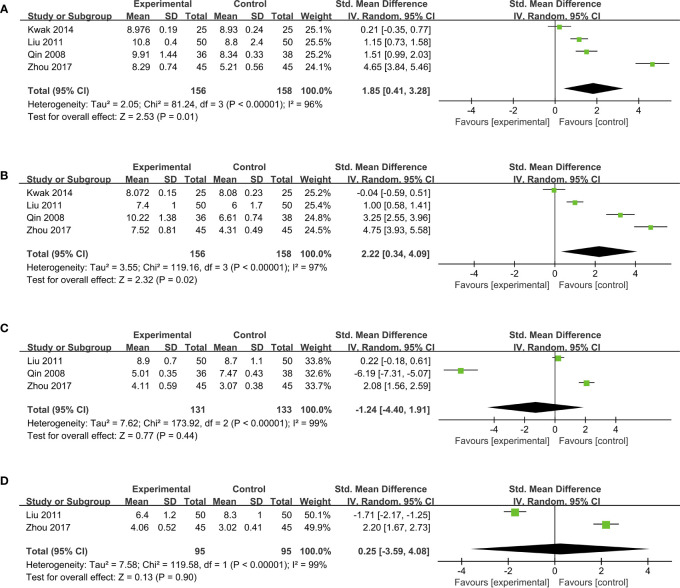

3.7. Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota compositions

Probiotics can also modulate the structure of gut microbiota. The data from Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, and Enterobacteriaceae were pooled into the meta-analysis. Four studies (24, 28, 31, 45) indicated that, compared to placebo groups, the supplementation of probiotics significantly boosted the enrichment of Bifidobacterium (SMD, 1.85, 95% CI, 0.41 to 3.28; P = 0.01) in a high heterogeneity (I2 = 96%; Figure 5A ). As for the abundance of Lactobacillus, a remarkable increase in probiotic groups was observed from the meta-analysis (SMD, 2.22; 95% CI, 0.34 to 4.09; P = 0.02; I2 = 97%) after pooling data from four studies (24, 28, 31, 45) ( Figure 5B ). However, no notable difference in Enterococcus levels between probiotics and placebo groups was presented in a forest plot containing data from three studies (28, 31, 45) (SMD, -1.24; 95% CI, -4.40 to 1.91; P = 0.44; Figure 5C ). Pooling data from two RCTs (28, 45) also indicated no significant change in the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae after probiotic intervention (SMD, 0.25; 95% CI, -3.59 to 4.08; P = 0.90; Figure 5D ).

Figure 5.

Forest plots of pooled data on the effect of probiotics on microbial abundance. (A) Bifidobacterium, (B) Lactobacillus, (C) Enterococcus, (D) Enterobacteriaceae.

4. Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis reviewed 28 studies and synthesized 26 studies to assess the effects of single- or multi-strain probiotics. Critical to this study is the fact that probiotics could significantly improve intestinal barrier function according to specific indicators ( Figure 6 ). The administration of probiotics significantly stimulated TER and decreased serum zonulin, ET, and LPS levels, as shown in the pooled results. However, we did not observe the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing the levels of fecal zonulin, L/E ratio, L/R ratio, DAO, and D-LA. The meta-analysis also indicated that probiotic supplementation could reduce inflammatory factors such as CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α but did not affect IL-10 and hsCRP. Furthermore, this study also demonstrated that probiotics could modulate gut microbiota compositions by elevating the abundances of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

Figure 6.

Graphical illustration describes the effect of probiotics in fortifying the intestinal barrier function in immune and inflammation diseases.

The administration of probiotics decreased the serum zonulin level, indicating a beneficial effect on the intestinal barrier. Zonulin, involved in macromolecule trafficking, is a physiological modulator of intercellular tight junctions, and zonulin level is a hallmark of evaluating intestinal permeability (46, 47). Elevated serum zonulin level is associated with intestinal barrier leakage, microecological dysregulation, and inflammation (42, 48). Fecal zonulin was not significantly correlated with any other markers, which implied that serum zonulin is a better indicator of intestinal permeability than fecal. Subgroup analysis of this study also revealed a significant reduction of fecal zonulin induced by probiotic intervention for less than six weeks. Furthermore, TER is relevant to transepithelial permeability, and increased TER levels of the probiotic group also demonstrated improved intestinal barrier functions.

Probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium can down-regulate the proportion of Gram-negative bacteria and reduce the gut-derived LPS production. Inflammatory cytokines, e.g., TNF-α and IL-1β (49, 50), which are crucial intestinal barrier destructors, can also be decreased, therefore protecting the intestinal barrier function (51). Probiotics are also found to modulate the properties of the mucus layer and improve intestinal epithelium permeability (52). A damaged intestinal barrier may lead to increased mucosal permeability and endotoxins entering the circulatory system. The intestinal mucosa with intact physiological function, constitutes a barrier to bacteria and endotoxin, which can stop the gut from leaking toxins and LPS into the blood. Our study proved that the consumption of probiotics could remarkably reduce circulating endotoxin and LPS, demonstrating probiotics’ benefiting role in maintaining gut homeostasis.

The high recovery rates and negligible effects on osmotic pressure in the recipient lumen make Lactulose, mannitol, and rhamnose ideal sugar molecular probes, and their excretion rate ratios (L/M, L/R) are widely accepted indicators to measure intestinal barrier function. In this study, probiotic supplementation did not significantly decrease the L/M ratio. In addition, the L/R ratio also showed no significant differences between probiotic groups and placebo groups.

DAO, a highly active intracellular enzyme in the cytoplasm of intestinal mucosal villous cells, can reflect the maturity and integrity of intestinal epithelial cells and is a sensitive indicator to show the functional status of the intestinal mucosal barrier. In our meta-analysis, five studies measured DAO and failed to achieve an effective reduction of DAO level. D-LA, another primary outcome measure regarding intestinal barrier function, has a significant positive correlation with intestinal mucosal injury scores. Still, there was no evidence to prove that probiotics reduced D-LA levels. However, noteworthy, only two studies were pooled into our analysis, and the forest plot of D-LA showed a high statistical heterogeneity, which suggested that more studies are warranted in the future to accurately determine the impact of probiotics on the gut barrier measured by D-LA.

Regarding the inflammation management of probiotics, we found that the concentrations of CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α dramatically decreased after probiotic treatment. CRP is an acute-phase reactant protein in the plasma, and concentrations increase significantly during acute and chronic inflammation (53). IL-6 is a lymphokine produced by activated T cells and fibroblasts, and TNF-α is the primary proinflammatory cytokine. IL-6 and TNF-α are cytokines that can disrupt the gut barrier integrity and indirectly increase intestinal permeability, thus resulting in bacteria translocation (54), which has been confirmed both in vivo and in vitro studies (55). Compared to control groups, a significant decrease in these inflammatory factors was observed in probiotic groups. Subgroup analysis further revealed that interventions of less than three months would exhibit better efficacy in reducing the yield of CRP and IL-6. It is believed that probiotics have a significant impact on the mucosal and systemic immune systems by activating multiple immune mechanisms, such as introducing a Th1 profile response with high levels of IL-10 (56). While the levels of IL-10 and immune indicators, such as IgA, IgG, and IgM, had no differences comparing probiotic groups to control groups in our study, indicating that probiotics did not demonstrate any significant improvement in immune functions.

Probiotics may also modulate the compositions of gut microbiota. There are a variety of typical microorganisms in the intestinal tract, and the commensal flora forms a biological barrier by adhering to or binding to the intestinal mucosa. Microorganisms that play an essential role in the intestinal biological barrier are some specific anaerobic bacteria, including Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. These specialized anaerobic bacteria tightly bind to the intestinal epithelium through adhesion and form a pellicle barrier, which can compete to inhibit the binding of pathogenic bacteria to the intestinal epithelium and inhibit their colonization and growth. Furthermore, our study found that intervention with probiotics increased the abundance of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which is beneficial for hindering a large amount of endotoxin from entering the circulatory system and preventing triggering functional damage to various organ systems (57).

We tried to assess the role of probiotics in improving intestinal barrier function comprehensively from various perspectives. In addition, subgroup meta-analyses were conducted according to multiple aspects, e.g., country, population characteristics, and study design. However, the limitations of the present study cannot be ignored when interpreting and extrapolating our findings. First, the heterogeneity of some analyses remained high even though a subgroup meta-analysis was performed, which may influence the accuracy of the results. Second, the type or other specific probiotics information in some studies was unclear, which limited further analysis. Furthermore, the included studies for meta-analysis measuring gut barriers involved a wide range of indicators, and different methods may lead to different results; therefore, more comprehensive studies will be warranted in the future to draw definitive conclusions about the role of probiotics on intestinal barrier function.

These findings suggested that probiotics could improve intestinal barrier function to some extent, but more high-quality RCTs are needed to achieve a solid conclusion. In addition, further in-depth research is required to target the precise dose, intervention duration, and strains of probiotics to provide valuable instructions for clinical practice.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

J-YW, HY, and C-SY conceived the idea for the paper. YZ, PT, ZZ, and YW conducted the literature searching, and meta-analysis. YZ, PT, ZZ, and HY conducted the quality assessment of included studies. YZ, PT, ZZ, AZ, J-YW, HY drafted the manuscript. C-ZW, C-SY contributed data analysis and revised the manuscript. All authors provided critical reviews and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973714, 82274379); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2022-JYB-JBZR-009); Beijing University of Chinese Medicine High-level Talent Start-up Research Project (2021-XJ-KYQD-004).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1143548/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; D-LA, D-lactic acid; DAO, diamine oxidase; ET, endotoxin; GI, gastrointestinal; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; I-FABP: intestinal fatty acid-binding protein; IL-6: interleukin 6; IL-10, interleukin 10; IgA, Immunoglobulin A; IgG, Immunoglobulin G; IgM, Immunoglobulin M; L/M, lactulose to mannitol; L/R, lactulose to rhamnose; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MD, mean difference; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; SMD, standard mean difference; TER, transepithelial resistance; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

References

- 1. Wells JM, Brummer RJ, Derrien M, Macdonald TT, Troost F, Cani PD, et al. Homeostasis of the gut barrier and potential biomarkers. Am J Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol (2017) 312:G171–93. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00048.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Camilleri M. Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut (2019) 68:1516–26. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Binienda A, Twardowska A, Makaro A, Salaga M. Dietary carbohydrates and lipids in the pathogenesis of leaky gut syndrome: an overview. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21:8368. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hiippala K, Jouhten H, Ronkainen A, Hartikainen A, Kainulainen V, Jalanka J, et al. The potential of gut commensals in reinforcing intestinal barrier function and alleviating inflammation. Nutrients (2018) 10:998. doi: 10.3390/nu10080988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Odenwald MA, Turner JR. The intestinal epithelial barrier: a therapeutic target? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2017) 14:9–21. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li XY, He C, Zhu Y, Lu NH. Role of gut microbiota on intestinal barrier function in acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol (2020) 26:2187–93. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i18.2187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mu QH, Kirby J, Reilly CM, Luo XM. Leaky gut as a danger signal for autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol (2017) 8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Régnier M, Van Hul M, Knauf C, Cani PD. Gut microbiome, endocrine control of gut barrier function and metabolic diseases. J Endocrinol (2021) 248:R67–82. doi: 10.1530/JOE-20-0473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chopyk DM, Grakoui A. Contribution of the intestinal microbiome and gut barrier to hepatic disorders. Gastroenterology (2020) 159:849–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR, Merenstein DJ, Pot B, et al. The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2014) 11:506–14. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu Q, Yu ZM, Tian FW, Zhao JX, Zhang H, Zhai QX, et al. Surface components and metabolites of probiotics for regulation of intestinal epithelial barrier. Microbial Cell Factories (2020) 19:23. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-1289-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu D, Jiang XY, Zhou LS, Song JH, Zhang X. Effects of probiotics on intestinal mucosa barrier in patients with colorectal cancer after operation: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (2016) 95:e3342. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj (2009) 339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program] . Version 5.4, the cochrane collaboration. (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luo DH, Wan X, Liu JM, Tong TJ. How to estimate the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, extremes or quartiles. Chin J Evidence-Based Med (2017) 17:1350–6. doi: 10.7507/1672-2531.201706060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alberda C, Gramlich L, Meddings J, Field C, Mccargar L, Kutsogiannis D, et al. Effects of probiotic therapy in critically ill patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Of Clin Nutr (2007) 85:816–23. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Besselink MG, Van Santvoort HC, Renooij W, De Smet MB, Boermeester MA, Fischer K, et al. Intestinal barrier dysfunction in a randomized trial of a specific probiotic composition in acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg (2009) 250:712–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bce5bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bonfrate L, Di Palo DM, Celano G, Albert A, Vitellio P, De Angelis M, et al. Effects of bifidobacterium longum BB536 and lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 in IBS patients. Eur J Clin Invest (2020) 50:e13201. doi: 10.1111/eci.13201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen H, Xia Y, Shi C, Liang Y, Yang Y, Qin H. Effects of perioperative probiotics administration on patients with colorectal cancer. Chin J Clin Nutr (2014) 22:74–81. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-635X.2014.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Roos NM, Van Hemert S, Rovers JMP, Smits MG, Witteman BJM. The effects of a multispecies probiotic on migraine and markers of intestinal permeability-results of a randomized placebo-controlled study. Eur J Clin Nutr (2017) 71:1455–62. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2017.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Horvath A, Leber B, Schmerboeck B, Tawdrous M, Zettel G, Hartl A, et al. Randomised clinical trial: the effects of a multispecies probiotic vs. placebo on innate immune function, bacterial translocation and gut permeability in patients with cirrhosis. Alimentary Pharmacol Ther (2016) 44:926–35. doi: 10.1111/apt.13788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kwak DS, Jun DW, Seo JG, Chung WS, Park SE, Lee KN, et al. Short-term probiotic therapy alleviates small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, but does not improve intestinal permeability in chronic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol (2014) 26:1353–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lamprecht M, Bogner S, Schippinger G, Steinbauer K, Fankhauser F, Hallstroem S, et al. Probiotic supplementation affects markers of intestinal barrier, oxidation, and inflammation in trained men; a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr (2012) 9:45. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-9-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leber B, Tripolt NJ, Blattl D, Eder M, Wascher TC, Pieber TR, et al. The influence of probiotic supplementation on gut permeability in patients with metabolic syndrome: an open label, randomized pilot study. Eur J Clin Nutr (2012) 66:1110–5. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu Z, Li C, Huang M, Tong C, Zhang X, Wang L, et al. Positive regulatory effects of perioperative probiotic treatment on postoperative liver complications after colorectal liver metastases surgery: a double-center and double-blind randomized clinical trial. BMC Gastroenterol (2015) 15:34. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0260-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu Z, Qin H, Yang Z, Xia Y, Liu W, Yang J, et al. Randomised clinical trial: the effects of perioperative probiotic treatment on barrier function and post-operative infectious complications in colorectal cancer surgery - a double-blind study. Alimentary Pharmacol Ther (2011) 33:50–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04492.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu ZH, Huang MJ, Zhang XW, Wang L, Huang NQ, Peng H, et al. The effects of perioperative probiotic treatment on serum zonulin concentration and subsequent postoperative infectious complications after colorectal cancer surgery: a double-center and double-blind randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr (2013) 97:117–26. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McNaught CE, Woodcock NP, Anderson AD, Macfie J. A prospective randomised trial of probiotics in critically ill patients. Clin Nutr (2005) 24:211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qin HL, Zheng JJ, Tong DN, Chen WX, Fan XB, Hang XM, et al. Effect of lactobacillus plantarum enteral feeding on the gut permeability and septic complications in the patients with acute pancreatitis. Eur J Clin Nutr (2008) 62:923–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sanaie S, Ebrahimi-Mameghani M, Hamishehkar H, Mojtahedzadeh M, Mahmoodpoor A. Effect of a multispecies probiotic on inflammatory markers in critically ill patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Res Med Sci (2014) 19:827–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sharma B, Srivastava S, Singh N, Sachdev V, Kapur S, Saraya A. Role of probiotics on gut permeability and endotoxemia in patients with acute pancreatitis a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Clin Gastroenterol (2011) 45:442–8. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318201f9e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shing CM, Peake JM, Lim CL, Briskey D, Walsh NP, Fortes MB, et al. Effects of probiotics supplementation on gastrointestinal permeability, inflammation and exercise performance in the heat. Eur J Appl Physiol (2014) 114:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2748-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sindhu KN, Sowmyanarayanan TV, Paul A, Babji S, Ajjampur SS, Priyadarshini S, et al. Immune response and intestinal permeability in children with acute gastroenteritis treated with lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis (2014) 58:1107–15. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smecuol E, Hwang HJ, Sugai E, Corso L, Chernavsky AC, Bellavite FP, et al. Exploratory, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effects of bifidobacterium infantis natren life start strain super strain in active celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol (2013) 47:139–47. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31827759ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Soldi S, Tagliacarne SC, Valsecchi C, Perna S, Rondanelli M, Ziviani L, et al. Effect of a multistrain probiotic (Lactoflorene® plus) on inflammatory parameters and microbiota composition in subjects with stress-related symptoms. Neurobiol Stress (2018) 10:100138. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stadlbauer V, Horvath A, Komarova I, Schmerboeck B, Feldbacher N, Klymiuk I, et al. Dysbiosis in early sepsis can be modulated by a multispecies probiotic: a randomised controlled pilot trial. Beneficial Microbes (2019) 10:265–78. doi: 10.3920/BM2018.0067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Toejing P, Khampithum N, Sirilun S, Chaiyasut C, Lailerd N. Influence of lactobacillus paracasei HII01 supplementation on glycemia and inflammatory biomarkers in type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Foods (2021) 10:1455. doi: 10.3390/foods10071455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Townsend JR, Bender D, Vantrease WC, Sapp PA, Toy AM, Woods CA, et al. Effects of probiotic (Bacillus subtilis DE111) supplementation on immune function, hormonal status, and physical performance in division I baseball players. Sports (2018) 6:70. doi: 10.3390/sports6030070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang J, Ke H, Liu KX, Qu JM. Effects of exogenous probiotics on the gut microbiota and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Palliative Med (2021) 10:1180–90. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wegh CAM, De Roos NM, Hovenier R, Meijerink J, Besseling-Van Der Vaart I, Van Hemert S, et al. Intestinal permeability measured by urinary sucrose excretion correlates with serum zonulin and faecal calprotectin concentrations in UC patients in remission. J Nutr Metab (2019) 2019:2472754. doi: 10.1155/2019/2472754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xia Y, Yang Z, Chen HQ, Qin HL. Effect of bowel preparation with probiotics on intestinal barrier after surgery for colorectal cancer. Zhonghua wei chang wai ke za zhi [Chinese J gastrointestinal surgery] (2010) 13:528–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang JW, Du P, Gao J, Yang BR, Fang WJ, Ying CM. Preoperative probiotics decrease postoperative infectious complications of colorectal cancer. Am J Med Sci (2012) 343:199–205. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31823aace6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhou XF, He Y, Wang SJ, Wang JM, Hong WY. Effect of probiotics on diarrhea secondary to chemotherapy for leukemia. World Chin J Digestology (2017) 25:3248–52. doi: 10.11569/wcjd.v25.i36.3248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fasano A. Zonulin and its regulation of intestinal barrier function: the biological door to inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Physiol Rev (2011) 91:151–75. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fasano A. Leaky gut and autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol (2012) 42:71–8. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8291-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tajik N, Frech M, Schulz O, Schalter F, Lucas S, Azizov V, et al. Targeting zonulin and intestinal epithelial barrier function to prevent onset of arthritis. Nat Commun (2020) 11:1995. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15831-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rodes L, Khan A, Paul A, Coussa-Charley M, Marinescu D, Tomaro-Duchesneau C, et al. Effect of probiotics lactobacillus and bifidobacterium on gut-derived lipopolysaccharides and inflammatory cytokines: an in vitro study using a human colonic microbiota model. J Microbiol Biotechnol (2013) 23:518–26. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1205.05018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu Y, Zhang H, Xie A, Sun J, Yang H, Li J, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus and l. plantarum combination treatment ameliorated colitis symptoms in a mouse model by altering intestinal microbial composition and suppressing inflammatory response. Mol Nutr Food Res (2023) e2200340. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202200340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Han H, You Y, Cha S, Kim TR, Sohn M, Park J. Multi-species probiotic strain mixture enhances intestinal barrier function by regulating inflammation and tight junctions in lipopolysaccharides stimulated caco-2 cells. Microorganisms (2023) 11:656. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11030656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. La Fata G, Weber P, Mohajeri MH. Probiotics and the gut immune system: indirect regulation. Probiotics Antimicrobial Proteins (2018) 10:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s12602-017-9322-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang L, Fan X, Zhong Z, Xu G, Shen J. Association of plasma diamine oxidase and intestinal fatty acid-binding protein with severity of disease in patient with heat stroke. Am J Emerg Med (2015) 33:867–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rohr MW, Narasimhulu CA, Rudeski-Rohr TA, Parthasarathy S. Negative effects of a high-fat diet on intestinal permeability: a review. Adv Nutr (2020) 11:77–91. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ye DM, Ma I, Ma TY. Molecular mechanism of tumor necrosis factor-alpha modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol (2006) 290:G496–504. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00318.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Galdeano CM, Cazorla SI, Dumit JML, Velez E, Perdigon G. Beneficial effects of probiotic consumption on the immune system. Ann Nutr Metab (2019) 74:115–24. doi: 10.1159/000496426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chen Y, Zhong Z, Liang Y, Wang A. Effect of probiotics on intestinal barrier function in patients with liver cirrhosis. Chin J Clin Gastroenterol (2010) 22:204–7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.