Abstract

Background

Recanalization in cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) can begin as early as 1 week after initiating therapeutic anticoagulation. The clinical significance of recanalization remains uncertain.

Objectives

We aimed to investigate the association between recanalization and functional outcomes and explored predictors of recanalization.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted (EMBASE, MEDLINE, Cochrane library) to identify: (1) patients with CVT aged ≥18 years treated with anticoagulation only; (2) case series, cohort, or randomized controlled trial studies; and (3) reported recanalization rates and functional outcomes using either a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) or sequelae of CVT at last follow-up. Meta-analysis was performed using pooled odds ratios (ORs) with exploration of sex and age effects using meta-regression.

Results

Twenty-three studies were eligible with 1418 individual patients in total. Timing of reimaging and clinical reassessment was variable. Absence of recanalization was associated with increased odds of an unfavorable functional outcome (mRS 2-6 versus 0-1; OR, 3.66; 95% CI, 1.73-7.74; p = 0.001), CVT recurrence (OR, 8.81; 95% CI, 1.63-47.7; p = 0.01), and chronic headache (OR, 2.78; 95% CI, 1.16-6.70; p = 0.02). On meta-regression, the relationship between recanalization and mRS differed by the proportion of female patients, where lower proportions of women were associated with higher likelihood of a worse outcome, but not by mean participant age. There was no incremental benefit of full compared with partial recanalization with respect to favorable mRS or recurrence, but odds of chronic headache were higher with partial versus full recanalization (OR, 3.80; 95% CI, 1.43-10.11; p = 0.008). Epilepsy and visual sequelae were not associated with recanalization.

Conclusions

Absence of recanalization was associated with worse functional outcomes, CVT recurrence, and headache, but outcomes were modified by sex. The degree of recanalization was significant in relation to headache outcomes, where partial compared with complete recanalization resulted in a greater likelihood of residual headache. Prospective studies with common timing of repeat clinical-neuroimaging assessments will help to better ascertain the relationship and directionality between the degree of recanalization and outcomes.

Keywords: cerebral venous thrombosis, headache, intracranial, meta-analysis, Modified Rankin Scale, prognosis, recanalization, recurrence, risk factors, sinus thrombosis, thrombosis, venous, vision

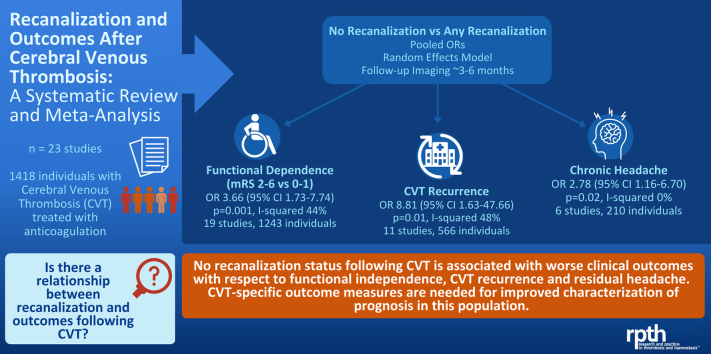

Graphical abstract

Essentials

-

•

The effect of recanalization on prognosis in cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is unestablished.

-

•

In our meta-analysis, we explored the relationship between CVT-specific outcomes and recanalization.

-

•

No recanalization corresponded to worse functional outcomes, chronic headache, and recurrence.

-

•

The relationship between recanalization and functional outcomes was modified by sex.

1. Introduction

The current management of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is mainly based on consensus guidelines. Anticoagulation remains the mainstay of treatment with the American Heart Association and the European Stroke Organization guidelines recommending 3 to 12 months' duration of therapy for first-time CVT not associated with a permanent prothrombotic state [1,2]. There is persistent uncertainty with regards to the optimal duration of therapy, timing, and role of reimaging in guiding decision-making around anticoagulation. Information to guide minimum safe length of anticoagulation in this patient population may reduce bleeding complications and optimize the quality of life [3].

Although some clinicians use repeat venous imaging to guide the duration of therapy [4], the significance of venous recanalization in relation to prognosis is not well established and practice patterns are variable. A 2018 meta-analysis found that recanalization was associated with a better prognosis after CVT [5]. However, in addition to heterogeneity of study quality and design, challenges with the literature to date in clarifying this issue include the following: (1) Lack of emphasis on the importance of timing of recanalization to prognosis. Few studies have performed prospective reimaging at prespecified timepoints and fewer still explore the prognostic significance of early recanalization (ie, before 90 days following presentation). (2) Limited definitions of prognosis. Most studies have focused on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), an ordinal functional outcome scale used in contemporary stroke trials where 0 indicates no symptoms and 6 is death. Scores of 0-1 indicate no limitation to previous activities (“excellent outcome”) and 0-2 indicate functional independence (favorable outcome) [6]. Thus, mRS incompletely captures the spectrum of common post-CVT sequelae such as headache, and issues with mood, fatigue, and cognition. (3) Limited exploration of the relationship between the degree of recanalization and prognosis in the context of variable definitions of recanalization between studies.

This systematic review and meta-analysis builds upon previous work by (1) including newer, large, and prospective studies, (2) exploring the relationship between the degree of recanalization and prognosis, and (3) defining prognosis with both mRS in addition to other post-CVT sequelae.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was registered prospectively with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42017074818), and adheres to the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

Studies were identified using MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to December 2, 2022. All searches were carried out without any language restriction using medical subject headings and free text keywords (complete search strategy is detailed in the Supplementary Material). Reference lists from included articles, review papers, and the authors’ own files were also reviewed for relevant studies.

2.2. Eligibility criteria and study selection

Specific criteria for the included studies were (1) case series of at least n = 5, observational study, or randomized controlled trial with adult (aged ≥18 years) human participants. If the series included pediatric patients, individual patient data for adult participants needed to be available; (2) neuroimaging-confirmed diagnosis of CVT by CT venography, MR venography or digital subtraction angiography (DSA); (3) treatment with anticoagulation only (ie, no thrombolysis, endovascular therapy or surgical intervention related to management of CVT), initiated at time of diagnosis; (4) follow-up vascular imaging at the time of hospital discharge or later; (5) characterization of venous recanalization on follow-up neuroimaging differentiating at minimum between “no recanalization” versus some degree of recanalization; and (6) functional outcome data with mRS and outcome data related to other post-CVT sequelae (eg, chronic headache, visual symptoms, and so forth) at discharge or later. For studies that reported functional outcome but did not use mRS, sufficient patient-level data was needed to derive mRS using a structured algorithm [6]. If data from the same cohort were published more than once, the publication with the largest number of participants was included. If a study included individual patient data and not all patients met the study inclusion criteria, only data from patients meeting the study inclusion criteria were included in the analysis where possible.

Two independent authors (D.J.K. and A.H.) performed the study selection process. After removing duplicate studies, selected studies were screened initially for potential eligibility by title and abstract analysis. There was a subsequent full-text review for eligible studies. Gray literature (ie, conference abstracts and proceedings) was excluded.

2.3. Outcomes and definitions

The prespecified primary outcome was functional prognosis as per mRS, dichotomized by unfavorable (mRS 2-6) and favorable (mRS 0-1). Secondary outcomes included CVT recurrence, the presence of chronic headache, epilepsy, new dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) formation, vision changes, and neuropsychiatric sequelae (eg, mood disorder, cognitive issues).

Timing to presentation was defined as time from symptom onset to diagnosis with imaging. Either “symptom onset to treatment” or “symptom onset to admission” was acceptable, with the presumption that admission and treatment were likely to be on the same day as diagnosis. In keeping with existing definitions in the current literature, acute presentation was defined as 48 hours or less from symptom onset to presentation; subacute presentation was defined as > 48 hours to 30 days, and chronic presentation as > 30 days.

Degree of recanalization, when specified, was classified as none, partial, or complete. When aggregating all studies, we consolidated partial and complete recanalization as “any recanalization” to account for any studies that did not specify between partial or complete recanalization.

2.4. Data extraction and quality assessment

The following information was extracted in duplicate by 2 authors (D.J.K., A.H.), with a third (T.S.F.) reviewing in cases of discrepancies: (1) Study characteristics: first author, design, major inclusion criteria, year of publication, country and setting of the study, reporting of individual patient data, total number of subjects, the number of subjects excluded by the authors with reasons stated (eg, pediatric patients, received endovascular therapy, and so forth), mean duration of follow-up, baseline and follow-up imaging modality, timing of clinical and imaging follow-up, the number of patients undergoing clinical and neuroimaging reassessment, definitions of recanalization, rater qualifications for clinical and imaging assessments if available, and anticoagulation strategy and duration. (2) Patient characteristics: age, sex, clinical risk factors for CVT. Definitions for risk factors are included in the Supplementary Material. (3) Characteristics at presentation: timing of presentation (acute, subacute or chronic), location of CVT, and presence of parenchymal lesions. (4) Outcomes: above, with study-specific outcome definitions where possible.

Data were extracted using a prespecified template. Corresponding authors were contacted for additional information if needed. Non-English articles were provisionally translated using Google Translate (translate.google.com), and then reviewed with a native speaker neurologist to ensure accurate data extraction.

2.5. Data synthesis and analysis

We calculated a meta-analysis of unadjusted odds ratio (OR) using the Mantel–Haenszel method, which performs better than inverse variance models in the setting of sparse data [7]. We performed a sensitivity analysis combining studies reporting only ORs using an inverse variance model. We used random-effects models in all instances given anticipated between-study heterogeneity. Forest plots were generated to display individual and pooled ORs. Heterogeneity was assessed with the Cochrane Q test and I2 statistic. Publication bias was assessed using Egger tests and visual inspection of the funnel plot for symmetry.

We calculated unadjusted ORs and performed meta-analysis to assess relations between clinical factors and the presence of no recanalization versus any recanalization. We then analyzed ORs of mRS 2-6 versus 0-1, given degrees of recanalization (no recanalization versus any recanalization, and, if there was a significant relationship, full recanalization versus partial, and none). Given their known status as variables associated with prognosis, we performed meta-regressions examining the effect of participant age (mean age of study cohort) and sex (proportion of female participants in study cohort) on ORs of functional status and recanalization for included studies.

All P values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, although we considered this when evaluating our results. Meta-analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.3 (Cochrane collaboration, 2020) and meta-regression with Comprehensive Meta-analysis 3.3.07 (Englewood, NJ).

2.6. Assessment of study quality

We used a modified version of a bias assessment tool used for observational stroke imaging studies, with additional guidance from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s “Study Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies” [8,9]. Overall, 16 questions evaluated patient selection, diagnosis, misclassification, reporting, attrition, and confounding bias (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Material). Two independent authors (D.J.K., A.A.) appraised the risk of bias with disagreements resolved by consensus (T.S.F.).

3. Results

3.1. Search and screening results

We screened a total of 879 nonduplicate articles (including 15 records obtained through handsearching), and identified 23 studies and in total 1418 study participants that met all inclusion criteria (Figure S1, Supplementary Material).

3.2. Study characteristics

Of the 23 studies, 7 were prospective, 2 were ambispective, and 6 were multicenter studies. The 2 largest studies consisted of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of 120 participants from 36 sites in 9 countries [10], and an international, multicenter prospective observational study with 508 participants across 28 sites [11]. Most studies were from Europe (16 of 23), 2 were from the USA, 3 from India, and 1 each from Australia and Mexico.

The minimum duration of anticoagulation was between 3 and 12 months in all studies, except 1 study whose treatment duration ranged as short as 1 month and 2 studies whose minimum treatment was 2 months [[12], [13], [14]]. Seven studies did not state the duration of treatment [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. When anticoagulation details were provided (20 of 23 studies), treatment was initiated with heparin/low molecular weight heparin, then maintenance oral anticoagulation with: vitamin K antagonists (10 of 23 studies, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs; 2 of 23 studies); oral anticoagulation unspecified (4 of 23 studies, or assigned to either vitamin K antagonists versus DOAC (3 of 23 studies). In the latter group, 1 study was a 1:1 randomized controlled trial [10], 1 study had 5% of participants receive DOAC [22], and 1 study had 10% on DOAC by follow-up [23]. One study clearly stated that all participants were immediately started on a DOAC after diagnosis [20]. Three studies did not provide any details on the anticoagulation treatment [[17], [18], [19]]. All studies used a combination of CT venography, MR venography, and at times additional conventional angiography for baseline and follow-up neuroimaging asides for 1 study which utilized T1, T2, and spin echo sequences on MR for baseline and follow-up imaging [24]. Another study utilized T1, T2, and spin echo sequences for follow-up imaging only [25]. The majority of studies (17 of 23) had clear, established definitions for recanalization and degrees of recanalization (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, Supplementary Material). The risk of bias was overall low for 7 of 23 studies (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Material).

Timing of reimaging was variable (Supplementary Table S5A, Supplementary Material). Nine studies had prespecified times for repeat neuroimaging, mostly at the 3- or 6-month timepoint. Five studies had serial timed repeat neuroimaging (Supplementary Table S5B, Supplementary Material). For those reimaged at 3 months or earlier, 82.1% had some degree of recanalization and 40.9% had complete recanalization. The proportions of patients with any recanalization and complete recanalization remained similar for studies with reimaging at later timepoints during the first year after presentation (6 months: 80.8% partial or complete recanalization, 36.9% complete recanalization; 12 months: 81.4% partial or complete, 49.2% complete).

3.3. Functional outcomes and recanalization

Outcomes reported by study are summarized in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S6). Overall, 21 studies reported the relationship between recanalization and prognosis with the mRS (Table 1). In total, 18 studies with 735 included patients had data suitable for calculating pooled ORs for no versus any recanalization in relation to functional outcome as per mRS [10,[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18],20,21,[23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]]. An additional study reported data from 508 patients [11] suitable for pooling with the other studies using inverse variance weighting. Overall, 14 studies with 564 included patients in total had data suitable for calculating pooled ORs by degree of recanalization [[15], [16], [17], [18],[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26],[28], [29], [30]]. When examining the effect sizes related to functional outcome and recanalization, the funnel plot was symmetric on visual inspection, and Egger’s test was not significant (Figure S2, Supplementary Material).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies for analysis of primary outcome (mRS 2-6 versus 0-1).

| Study number | Study author (Year) | Timing of repeat imaging | Timing of repeat clinical assessment | Degree of recanalization (N, %) | mRS 0-1 (N, %) | mRS 2-6 (N, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aguiar de Sousa (2020) [22] | 3 mo | 3 mo | Complete | 33/61 (54%) | 28/61 (46%) | 5/61 (8%) |

| Partial | 27/61 (44%) | 21/61 (34%) | 7/61 (12%) | ||||

| None | 1/61 (2%) | ||||||

| 2 | Arauz (2016) [26] | Every 3 mo until recanalization up until 12 mo | Every 3 mo until recanalization up until 12 mo | Complete | 67/102 (66%) | 61/102 (60%) | 6/102 (6%) |

| Partial | 28/102 (27%) | 27 /102 (26%) | 1/102 (1%) | ||||

| None | 7/102 (7%) | 4 (4%) | 3/102 (3%) | ||||

| 3 | Bosch (1998) [24] | 6 mo | 6 mo | Complete | 0/8 | 0 | 0 |

| Partial | 5/8 (63%) | 5/8 (63%) | 0 | ||||

| None | 3/8 (37%) | 3/8 (37%) | 0 | ||||

| 4 | Brucker (1998) [15] | Mean 3 wk | Discharge (mean 4.6 wk) | Complete | 18/42 (43%) | 16/42 (38%) | 2/42 (5%) |

| Partial | 18/42 (43%) | 18/42 (43%) | 0 | ||||

| None | 6/42 (14%) | 5/42 (12%) | 1/42 (2%) | ||||

| 5 | Cakmak (2003) [13] | 2 mo | 3 mo | Any | 12/16 (75%) | 6/16 (37.5%) | 6/16 (37.5%) |

| None | 4/16 (25%) | 3/16 (19%) | 1/16 (6%) | ||||

| 6 | Cipri (1998) [27] | 3-24 mo (median 13 mo) | 3-7 wk (mean 5 wk) | Any | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| None | 7/7 | 6/7 (86%) | 1/7 (14%) | ||||

| 7 | Covut (2019) [28] | 1-18 mo (median 2 mo) | Discharge | Complete | 3/9 (33%) | 3/9 (33%) | 0 |

| Partial | 2/9 (22%) | 2/9 (22%) | 0 | ||||

| None | 4/9 (44%) | 3/9 (33%) | 1/9 (11%) | ||||

| 8 | Farrag (2010) [16] | 1-6 mo (mean 4 mo) | Discharge | Complete | 3/12 (25%) | 3/12 (25%) | 0 |

| Partial | 7/12 (58%) | 5/12 (42%) | 2/12 (16%) | ||||

| None | 2/12 (17%) | 0 | 2/12 (17%) | ||||

| 9 | Favrole (2004) [17] | 2-3 mo | 2-3 mo | Complete | 15/26 (58%) | 14/26 (54%) | 1/26 (4%) |

| Partial | 8/26 (31%) | 8/26 (31%) | 0 | ||||

| None | 3/26 (11%) | 3/26 (11%) | 0 | ||||

| 10 | Ferro (2022) [10] | 6 mo | 6 mo | Any | 92/108 (85%) | 87/108 (80%) | 5/108 (5%) |

| None | 16/108 (15%) | 14/108 (13%) | 2/108 (2%) | ||||

| 11 | Flotho (1999) [18] | Mean 6 mo (1 week-2.5 y) | Mean 6 mo (1 wk-2.5 y) | Complete | 6/22 (27%) | 6/22 (27%) | 0 |

| Partial | 9/22 (41%) | 8/22 (36%) | 1/22 (5%) | ||||

| None | 7/22 (32%) | 6/22 (27%) | 1/22 (5%) | ||||

| 12 | Herweh (2016) [12] | Median 7 mo (1 week-53 mo) | Median 8 mo (1-88 mo) | Any | 86/99 (87%) | 78/99 (79%) | 8/22 (36%) |

| None | 13/99 (13%) | 13/99 (13%) | 0 | ||||

| 13 | Mendonca (2015) [14] | 1-10 mo (median 5 mo) | 6 mo | Any | 12/15 (80%) | 10/15 (67%) | 2/15 (13%) |

| None | 3/15 (20%) | 3/15 (20%) | 0 | ||||

| 14 | Putaala (2010) [29] | 3 mo or later | 6 mo | Complete | 43/91 (47%) | 35/91 (38%) | 8/91 (9%) |

| Partial | 31/91 (34%) | 28/91 (31%) | 3/91 (3%) | ||||

| None | 17/91 (19%) | 10/91 (11%) | 7/91 (8%) | ||||

| 15 | Rezoagli (2018) [11] | Median 6-12 mo | Median 6-12 mo (Data here for those assessed at 6-12 mo) | Complete | 72/150 (48%) | 137/145 (94%) | 8/145 (5%) |

| Partial | 48/150 (32%) | ||||||

| None | 30/150 (20%) | ||||||

| 17 | Schultz (1996) [25] | 2 wk-68 mo | 5 mo-68 mo | Complete | 3/9 (33%) | 3 (33%) | 0 |

| Partial | 6/9 (67%) | 5/9 (56%) | 1/9 (11%) | ||||

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 18 | Shankar Iyer (2018) [20] | 3-9 mo (mean 6 mo) | 3-9 mo (mean 6 mo) | Complete | 12/19 (63%) | 11/19 (58%) | 1/19 (5%) |

| Partial | 7/19 (37%) | 7/19 (37%) | 0 | ||||

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 19 | Singh (2020) [21] | 6 mo | 6 mo | Complete | 6/33 (18%) | 5/33 (15%) | 1/33 (3%) |

| Partial | 23/33 (70%) | 19/33 (58%) | 4/33 (12%) | ||||

| None | 4/33 (12%) | 3/33 (9%) | 1/33 (3%) | ||||

| 20 | Stolz (2004) [44] | 12 mo | 12 mo (data here for 12 mo only) | Complete | 20/37 (54%) | 33/37 (89%) | 4/37 (11%) |

| Partial | 7/37 (19%) | ||||||

| None | 10/37 (27%) | ||||||

| 22 | Vanukuri (2022) [23] | Every 3 mo until 12 mo or complete recanalization (whichever first) | Every 3 mo until 12 mo or complete recanalization (whichever first) | Complete | 81/120 (67%) | 80/120 (66%) | 1/120 (1%) |

| Partial | 26/120 (22%) | 26/120 (22%) | 0/120 | ||||

| None | 13/120 (11%) | 4/120 (3%) | 9/120 (8%) | ||||

| 23 | Zimny (2017) [30] | 2 wk-45 mo (mean 39 wk) | 2 wk-45 mo (mean 39 wk) | Complete | 5/10 (50% | 5/10 (50% | 0 |

| Partial | 3/10 (30%) | 2/10 (20%) | 1/10 (10%) | ||||

| None | 2/10 (20%) | 0 | 2/10 (20%) | ||||

Studies 16 and 21 had non-mRS outcome data only and were thus excluded from this table.

mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

The median time to last follow-up neuroimaging was 6 months and the median time to last assessment of prognosis was 6 months. Overall, in comparison to any recanalization, no recanalization was associated with an increased odds of an unfavorable outcome (mRS 2-6 versus 0-1; OR, 3.82; 95% CI, 1.57-9.30; p = 0.003; I2, 46%). Heterogeneity was high (Table 2, Figure 1). Excluding studies of lower quality increased the effect size with higher heterogeneity (OR, 7.42; 95% CI, 1.79-30.70; p = 0.006; I2, 69%). One large study describing ORs only was analyzed with the other studies using inverse variance weighting [11]; this did not substantially change our findings (mRS 2-6 versus 0-1; OR, 3.66; 95% CI, 1.73-7.74; p = 0.001; I2, 44%). There was no significant difference in the odds of an unfavorable outcome with partial as compared with full recanalization (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.88-2.78; p = 0.13; I2, 43%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of the relationship between recanalization and prognosis.

| Outcome | Comparison | OR | 95% CI | I2 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRS 2-6 vs. 0-1: pooled ORs | No recanalization versus any | 3.82 | 1.57-9.30 | 46 | 0.003 |

| mRS 2-6 vs. 0-1 | No or partial recanalization versus complete | 1.57 | 0.88-2.78 | 43 | 0.13 |

| CVT recurrence | No recanalization versus any | 8.81 | 1.63-47.7 | 48 | 0.01 |

| CVT recurrence | No or partial recanalization versus complete | 2.10 | 0.62-7.13 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Chronic headache | No recanalization versus any | 2.78 | 1.16-6.70 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Chronic headache | No or partial recanalization versus complete | 4.09 | 1.65-10.15 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Chronic headache | Partial recanalization versus complete | 3.80 | 1.43-10.11 | 0 | 0.008 |

| Epilepsy | No recanalization versus anya | 0.92 | 0.18-4.76 | 0 | 0.92 |

| Visual sequelae | No recanalization versus anya | 8.28 | 0.89-77.4 | 0 | 0.06 |

Complete versus partial recanalization not assessed as there was no significant relationship between no recanalization versus any recanalization.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Figure 1.

Forest plot displaying pooled odds ratios (OR) measuring association between recanalization status (none versus any) and unfavorable outcomes (mRS 2-6).

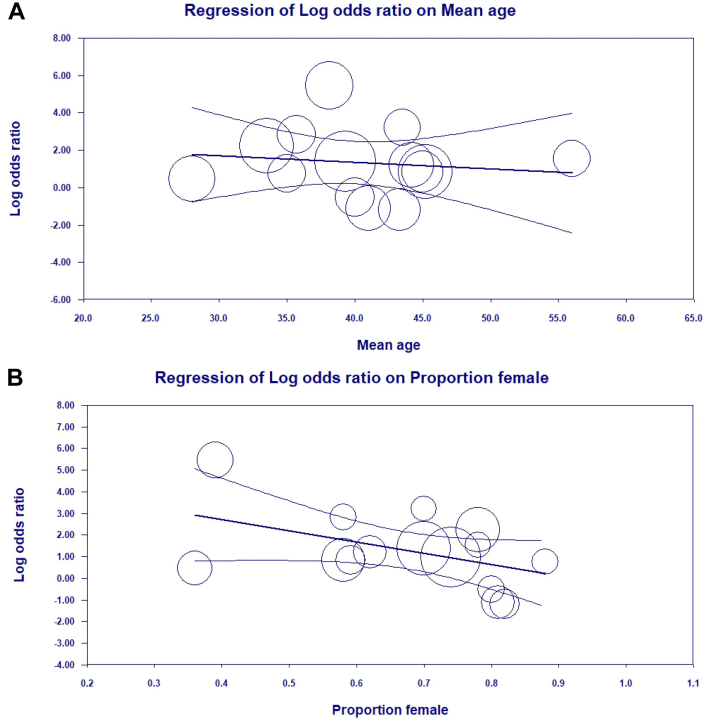

In meta-regression, the relationship between recanalization and prognosis did not change with the mean age of the study cohort. However, there was a significant effect of sex on the relationship between recanalization and prognosis, where studies with higher proportions of men demonstrated a higher likelihood of a worse prognosis than studies with more women (β= −5.19; 95% CI, −10.15 to −0.23; p = 0.04; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-regression plots depicting the effect of mean age and sex on the relationship between recanalization status (none versus any) and functional outcomes (mRS 2-6 versus 0-1). (A) There is no effect of mean age on the relationship between recanalization and mRS outcomes (β= −0.04; 95% CI, −0.1854 to 0.1148; p = 0.65). (B) The modifying effect of sex was significant (β = −5.19; 95% CI, −10.15 to −0.23; p = 0.04). Y-axis, log odds ratio (OR) of mRS 2-6 vs. 0-1 for no versus any recanalization; X-axis, mean age in the study cohort (A) and proportion of female patients in the study cohort (B). Curved lines depict 95% confidence interval, and circles represent individually weighted studies. Log OR > 0 favors no recanalization, and <0 favors any recanalization.

3.4. CVT recurrence

Eleven studies with 566 patients in total reported rates of CVT recurrence in relation to recanalization status [12,[14], [15], [16],[19], [20], [21],23,25,26,29]. Only 1 study included a definition of recurrence, which was “presence of symptoms suggestive of [CVT] and either extension of the previous thrombus or re-occlusion of the sinuses” [23]. As compared with any recanalization, no recanalization was associated with an increased odds of recurrence (OR, 8.81; 95% CI, 1.63-47.66; p = 0.01; I2, 48%). Partial recanalization was not associated with a difference in recurrence compared with complete recanalization (Table 2).

3.5. Chronic headache

Six studies with 210 patients reported data for pooled ORs examining the relationship between chronic headache and recanalization [16,21,24,29,31]. One additional study reported that headache was not associated with recanalization status, but without data for extraction [22]. Definitions of chronic headache between studies and timing of assessments are summarized in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S7). No recanalization as compared with any recanalization was associated with an increased odds of chronic headache (OR, 2.78; 95% CI, 1.16-6.70; p = 0.02, I2, 0%). When examining the relationship between headache and degree of recanalization, partial recanalization was associated with a higher odds of headache than complete recanalization (partial versus complete, OR, 3.80; 95% CI, 1.43-10.11; p = 0.008, I2, 0%; Table 2).

3.6. Epilepsy, dAVF, vision outcomes, and neuropsychiatric sequalae

Three studies including 65 patients reported the relationship between recanalization and epilepsy [18,21,30]. Two others reported rates of epilepsy without data suitable for OR pooling [14,29]. Rates of epilepsy ranged from 6.6% to 50%. There was no association between recanalization status and epilepsy (Table 2).

One study examined the association between recanalization status and dAVF. At 6 month follow-up, 16.7% (4 of 24) had dAVF; this was a de novo finding in 2 patients [19]. Of those 2 patients with de novo dAVF, 1 had complete recanalization and then experienced re-thrombosis; the other experienced thrombus progression. Both patients with dAVF at baseline had incomplete recanalization at follow-up.

Three studies including 64 patients reported visual sequelae and recanalization status [18,21,25]. No recanalization was directionally associated with worse visual outcomes with low heterogeneity; however, this association did not reach statistical significance (OR, 8.28; 95% CI, 0.89-77.41; p = 0.06; I2, 0%; Table 2). In 1 study, 1 patient with partial recanalization had severe bilateral optic atrophy as a consequence of refractory papilledema [25]. Another study reported persistent papilledema in 6.1% (2 of 33) in follow-up; 1 patient had partial and the other had no recanalization [21]. The third study reported chronic visual sequelae in 9.1% (2 of 22), although further details were unavailable [18].

One study reported neuropsychological deficits in 1 patient with absent recanalization status; specific symptoms were not described [18].

3.7. Demographic, clinical, and radiological factors and recanalization

A full list of demographic, clinical, and radiological factors examined in relation to recanalization is listed in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Tables S8 and S9). Overall, only age >50 was associated with no recanalization (OR, 4.14; 95% CI, 1.88-9.14; p < 0.001; I2, 0%). Sex was not associated with recanalization status. There were no baseline radiological features, including deep venous system involvement, presence of venous hemorrhage, presence of parenchymal lesions or edema, isolated superior sagittal sinus involvement, or single versus multiple sinus involvement, which were associated with recanalization status. No specific provoking factor was associated with recanalization status, but there was a greater chance of no recanalization with cryptogenic etiology (OR, 3.63; 65% 1.71-7.70; p < 0.001; I2, 0%).

4. Discussion

In this updated systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that lack of recanalization was associated with increased odds of an unfavorable prognosis as well as an increased rate of recurrent CVT. The relationship between recanalization and prognosis was associated with sex, where studies with greater proportions of men had an increased odds of worse outcomes with absent recanalization. Although sequelae, including headache, fatigue, seizures, visual sequelae, and neuropsychiatric issues are common following CVT, these outcomes were rarely reported in relation to recanalization status. Timing of follow-up neuroimaging in these studies was also heterogeneous, with the majority of studies not performing follow-up vascular neuroimaging until the 3-month mark or later.

Our findings are in keeping with a 2018 meta-analysis which found an association between recanalization and favorable outcome (mRS 0-1) [5]. These results differ, however, from those of 2 recent high-quality prospective studies. Neither a subanalysis from the randomized RE-SPECT CVT trial [10], nor a prospective neuroimaging cohort study, PRIORITy-CVT [22], found an association between recanalization and favorable prognosis as per mRS. Both may have been underpowered to detect an association. In the RE-SPECT CVT trial, 91% of 120 patients achieved an mRS of 0-1 by 6 months. PRIORITy-CVT included 68 patients, 74% of whom had at least partial recanalization after 8 days of anticoagulation.

It is likely that the true relationship between recanalization and prognosis is both mediated by the timing of recanalization, and how the prognosis is defined. Most studies examining recanalization in CVT, in line with clinical practice, have focused on repeat imaging at the 90-day mark or later (Table 1), and most studies have used mRS to define prognosis. mRS outcomes alone do not fully reflect the experience of this generally young and high-functioning patient population [32,33]. Many CVT survivors, despite being functionally independent, may experience symptoms that are incompletely captured by mRS and may still reduce the quality of life, impacting return to education or employment [32,34]. Many of these factors have not been frequently examined, and some not at all, in relation to recanalization. Although the prospective PRIORITy-CVT study did not find an association between recanalization and prognosis based on mRS 0-1, the study did find that partial or complete recanalization after only 8 days of anticoagulation was associated with less progression and early improvement of nonhemorrhagic parenchymal lesions. PRIORITy-CVT is unique in its focus on very early vascular reimaging, and it is possible that if more sensitive outcome measures are used, the relationship between reduced parenchymal injury with early recanalization may truly translate to a better clinical prognosis. In addition to more sensitive outcomes, a better understanding of how the timing of recanalization may impact the prognosis, using serial imaging and beginning early in the disease course, will help to further clarify optimal clinical management.

This study assessed the use of patient-centered, CVT-related outcomes in recanalization studies. Overall, non-mRS-related outcomes were not well represented. We found that a lack of recanalization predicted chronic headache, and that partial recanalization was associated with a higher odds of headache than complete recanalization. Although this difference could be explained by reduced intracranial pressure in those who fully recanalize, venous collateralization over time may help to normalize intracranial pressure. Thus, prospective studies with repeat longitudinal assessments will help to clarify these issues to inform future clinical care. Other hemodynamic-related outcomes that could be plausibly associated with recanalization, such as chronic visual loss related to increased intracranial pressure or dAVF formation, have not explored most studies.

Absence of recanalization was also associated with increased odds of CVT recurrence, although risk was not further reduced by the degree of recanalization. As definitions of CVT recurrence can vary between studies, with “recurrence” inconsistently referring to the extension of index thrombus versus thrombus in a new vessel, common data elements will also help to clarify the importance of recanalization for this outcome. Recurrence may also be incompletely characterized because of the short duration of follow-up. Most studies did not assess participants later than 12 months post-event; most recurrent venous thromboembolism after CVT occurs over the longer term [35].

We explored the modifying effects of age and sex on the relationship between recanalization and outcomes. Older age, a known risk factor for worse prognosis after CVT, was associated with increased odds of no recanalization [33]. The mean study age was not associated with outcomes on meta-regression likely reflects the similar mean age of participants between studies. In meta-regression, we found a significant association between sex and the relationship between recanalization and prognosis. Male sex is a known factor associated with a worse prognosis in CVT [33], and the relationship between recanalization and prognosis seen in this meta-analysis may be mediated in part by sex-related differences in prognosis. Both biological and social differences may contribute to sex disparities in outcomes. A large prospective study demonstrated that female-specific risk factors of puerperium and exogenous hormonal therapy use are correlated with favorable outcomes, possibly rationalized by the predilection for women to be younger on average almost a decade, healthier and seek attention more from health care providers [36,37]. Females additionally tend toward lower rates of head trauma in the CVT literature [36]. None of the studies provided information on race/ethnicity, and thus the authors are unable to comment on how other baseline demographic factors may influence the relationship between recanalization and outcome. Notably, there is an imbalanced geographic representation of patients as the majority of data were collected at European sites across all studies. Race and ethnicity are under-reported in the CVT literature, and epidemiological information is lacking on these factors per various geographic regions. Only more recent data from ACTION-CVT, a retrospective international cohort study, demonstrated that black race was significantly associated with poor mRS outcomes at 3 months [38]. This is largely attributed to disparities in social determinants of health, but further exploration of contributing factors is needed. Future studies should specify race and ethnic variables with geographic data to better understand any interaction with CVT outcomes.

This work adds to the current state of knowledge through its inclusion of recent prospective studies, exploration of the role of the degree of recanalization in prognosis, and review of the current literature in characterizing multiple patient-centered outcomes as they pertain to recanalization. Importantly, we identify existing knowledge gaps and priorities for future research.

There are limitations to our meta-analysis. Definitions of recanalization grades varied between studies (Supplementary Table S3A), which is a limitation of the current literature and an opportunity to adopt a common grading scale for recanalization in future work. Recanalization ratings per Qureshi were most consistently used in the included studies; however, several studies did not report definitions, or were lacking detail regarding the recanalization of individual vessels in the case of some grading systems [39]. Furthermore, vascular imaging techniques varied between studies (Supplementary Table S3B), although most studies used a consistent technique for follow-up. Sensitivity for assessing recanalization grade, particularly in the cases of partial recanalization, may vary by modality. Against cerebral angiography as the standard reference for visualizing cerebral venous sinuses, MR venography showed 85% sensitivity for both time-of-flight and contrast-enhanced sequences, with higher specificity for the former, whereas CT venography sensitivity rose to 95% [40,41]. Thus, particularly in cases of determining the extent of partial versus full recanalization, there may be additional heterogeneity between studies introduced by imaging technique. Still, limitations related to recanalization scoring as well as imaging modality are mitigated by our analyses that group any partial and full recanalization together as “any recanalization,” compared with “no recanalization.” Additional limitations of our work, including heterogeneous study quality, variable timing of repeat neuroimaging between studies, and incomplete characterization of prognosis, reflect those of the literature to date and underscore the importance of prospective data collection as well as common data elements and timing of repeat assessments. Encouragingly, there is an emerging body of high-quality prospective research that will help to further clarify treatment strategies and prognosis after CVT.

Additional considerations are that we had insufficient data to examine recanalization and prognosis stratified by the type of oral anticoagulation, and we excluded patients who received endovascular therapy or were not candidates for anticoagulation. To date, studies comparing DOACs to warfarin for CVT have not found significant differences in rates of recanalization [42,43]. Although endovascular therapy is not the routine standard of care in CVT, it continues to be used in a clinical setting, and future studies examining the relationship between recanalization and outcomes may need to consider any effect modification related to endovascular versus medical therapy alone. Patients with complex CVT having contraindications to anticoagulation, including those with severe head trauma, represent a growing proportion of all admitted patients with CVT, and their course with respect to recanalization is also in need of further prospective study.

5. Conclusions

We found that in patients with CVT, a lack of recanalization was associated with a less favorable functional prognosis, an increased risk of recurrence, and increased likelihood of chronic headache. The degree of recanalization was associated with headache, with partial recanalization having a higher odds than complete. No other outcomes were associated with the degree of recanalization. Between-study heterogeneity with respect to the relationship between functional outcome and recanalization may be explained in part by sex-related differences in prognosis. Our findings reiterate those of a previous meta-analysis but have not been redemonstrated in recent individual prospective studies, suggesting a need for improved characterization of prognosis in CVT research. Other priorities for future studies include high-quality prospective data with serial longitudinal imaging starting early in the disease course to clarify how timing of recanalization may impact outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dean Giustini and Charlotte Beck for their assistance in developing the search strategy.

Funding

T.S.F. is supported by a Sauder Family/Heart and Stroke Professorship of Stroke Research from the University of British Columbia, the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Author contributions

A.H. and D.J.K. developed the search strategy, performed article screening and data extraction, and drafted sections of the manuscript. A.A. appraised studies for the risk of bias and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. A.S. performed the preliminary analysis and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. L.W.Z. revised the manuscript for intellectual content. T.S.F. conceived of the study, performed the analysis, wrote sections of the draft, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Relationship Disclosure

T.S.F. receives in-kind study medication from Bayer Canada. The remaining authors had no disclosures.

Data availability

Data, data extraction templates, and analytic code are available on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Dr Mary Cushman

Diana J. Kim and Asaf Honig contributed equally to this study as co-first authors.

Supplementary material The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpth.2023.100143

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Saposnik G., Barinagarrementeria F., Brown R.D., Jr., Bushnell C.D., Cucchiara B., Cushman M., et al. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:1158–1192. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e31820a8364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferro J.M., Bousser M.-G., Canhão P., Coutinho J.M., Crassard I., Dentali F., et al. European Stroke Organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis - endorsed by the European Academy of Neurology. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:1203–1213. doi: 10.1111/ene.13381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casais P., Meschengieser S.S., Sanchez-Luceros A., Lazzari M.A. Patients’ perceptions regarding oral anticoagulation therapy and its effect on quality of life. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1085–1090. doi: 10.1185/030079905X50624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Field T.S., Camden M.-C., Al-Shimemeri S., Lui G., Lee A.Y.Y. Antithrombotic strategy in cerebral venous thrombosis: differences between neurologist and hematologist respondents in a Canadian survey. Can J Neurol Sci. 2017;44:116–119. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2016.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguiar de Sousa D., Lucas Neto L., Canhão P., Ferro J.M. Recanalization in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2018;49:1828–1835. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruno A., Shah N., Lin C., Close B., Hess D.C., Davis K., et al. Improving modified Rankin Scale assessment with a simplified questionnaire. Stroke. 2010;41:1048–1050. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.571562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Efthimiou O., Rücker G., Schwarzer G., Higgins J.P.T., Egger M., Salanti G. Vol. 38. Stat Med. Wiley; 2019. pp. 2992–3012. (Network meta-analysis of rare events using the Mantel-Haenszel method). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta A., Giambrone A.E., Gialdini G., Finn C., Delgado D., Gutierrez J., et al. Silent brain infarction and risk of future stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2016;47:719–725. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies [Internet]. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: Study Quality Assessment Tools. [cited 2020 May 18] https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools Available from:

- 10.Ferro J.M., Bendszus M., Jansen O., Coutinho J.M., Dentali F., Kobayashi A., et al. Recanalization after cerebral venous thrombosis. A randomized controlled trial of the safety and efficacy of dabigatran etexilate versus dose-adjusted warfarin in patients with cerebral venous and dural sinus thrombosis. Int J Stroke. 2022;17:189–197. doi: 10.1177/17474930211006303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rezoagli E., Martinelli I., Poli D., Scoditti U., Passamonti S.M., Bucciarelli P., et al. The effect of recanalization on long-term neurological outcome after cerebral venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:718–724. doi: 10.1111/jth.13954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herweh C., Griebe M., Geisbüsch C., Szabo K., Neumaier-Probst E., Hennerici M.G., et al. Frequency and temporal profile of recanalization after cerebral vein and sinus thrombosis. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:681–687. doi: 10.1111/ene.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cakmak S., Derex L., Berruyer M., Nighoghossian N., Philippeau F., Adeleine P., et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: clinical outcome and systematic screening of prothrombotic factors. Neurology. 2003;60:1175–1178. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055811.05743.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendonça M.D., Barbosa R., Cruz-e-Silva V., Calado S., Viana-Baptista M. Oral direct thrombin inhibitor as an alternative in the management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a series of 15 patients. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:1115–1118. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brucker A.B., Vollert-Rogenhofer H., Wagner M., Stieglbauer K., Felber S., Trenkler J., et al. Heparin treatment in acute cerebral sinus venous thrombosis: a retrospective clinical and MR analysis of 42 cases. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1998;8:331–337. doi: 10.1159/000015876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrag A., Irfan M., Guliani G.K., Tariq N., Taylor R.A., Suri M.F.K., et al. Occurrence of post-acute recanalization and collateral formation in patients with cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. A serial venographic study. Neurocrit Care. 2010;13:373–379. doi: 10.1007/s12028-010-9394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Favrole P., Guichard J.-P., Crassard I., Bousser M.-G., Chabriat H. Diffusion-weighted imaging of intravascular clots in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2004;35:99–103. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000106483.41458.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flotho E., Druschky K., Niederstadt T. Diagnostische Wertigkeit des kombinierten Einsatzes von Kernspintomo- und Kernspinangiographie bei Sinusvenenthrombosen (SVT) Fortschritte der Neurologie · Psychiatrie. 1999;67:95–103. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuchardt F.F., Demerath T., Elsheikh S., Wehrum T., Harloff A., Urbach H., et al. Dural arteriovenous fistula formation secondary to cerebral venous thrombosis: longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging assessment using 4D-Combo-MR-Venography. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121:1345–1352. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1723991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shankar Iyer R., Tcr R., Akhtar S., Muthukalathi K., Kumar P., Muthukumar K. Is it safe to treat cerebral venous thrombosis with oral rivaroxaban without heparin? A preliminary study from 20 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;175:108–111. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh V.K., Jain N., Kalita J., Misra U.K., Kumar S. Significance of recanalization of sinuses and resolution of parenchymal lesion in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;77:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aguiar de Sousa D., Lucas Neto L., Arauz A., Sousa A.L., Gabriel D., Correia M., et al. Early recanalization in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis treated with anticoagulation. Stroke. 2020;51:1174–1181. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanukuri N.K., Pedapati R., Shanmugam S., Hazeena P., Rangasami R., Venkatasubramanian S. Effect of recanalization on clinical outcomes in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis – an ambispective study. Eur J Radiol. 2022;153 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2022.110385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosch J., Rovira A., Álvarez-Sabín J., Capellades S. Valor de la RM craneal en el seguimiento de las trombosis de senos durales. Rev Neurol. 1998;3:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schultz D.W., Davis S.M., Tress B.M., Kilpatrick C.J., King J.O. Recanalisation and outcome cerebral venous thrombosis. J Clin Neurosci. 1996;3:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0967-5868(96)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arauz A., Vargas-González J.-C., Arguelles-Morales N., Barboza M.A., Calleja J., Martínez-Jurado E., et al. Time to recanalisation in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis under anticoagulation therapy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:247–251. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-310068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cipri S., Gangemi A., Campolo C., Cafarelli F., Gambardella G. High-dose heparin plus warfarin administration in non-traumatic dural sinuses thrombosis. A clinical and neuroradiological study. J Neurosurg Sci. 1998;42:23–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Covut F., Kewan T., Perez O., Flores M., Haddad A., Daw H. Apixaban and rivaroxaban in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2019;173:77–78. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Putaala J., Hiltunen S., Salonen O., Kaste M., Tatlisumak T. Recanalization and its correlation to outcome after cerebral venous thrombosis. J Neurol Sci. 2010;292:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimny A., Dziadkowiak E., Bladowska J., Chojdak-Łukasiewicz J., Loster-Niewińska A., Sąsiadek M., et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis as a diagnostic challenge: clinical and radiological correlation based on the retrospective analysis of own cases. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:1113–1122. doi: 10.17219/acem/66778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strupp M., Covi M., Seelos K., Dichgans M., Brandt T. Cerebral venous thrombosis: Correlation between recanalization and clinical outcome - a long-term follow-up of 40 patients. J Neurol. 2002;249:1123–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0749-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koopman K., Uyttenboogaart M., Vroomen P.C., van der Meer J., De Keyser J., Luijckx G.-J. Long-term sequelae after cerebral venous thrombosis in functionally independent patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferro J.M., Canhão P., Stam J., Bousser M.-G., Barinagarrementeria F., ISCVT Investigators Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT) Stroke. 2004;35:664–670. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000117571.76197.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji K., Zhou C., Wu L., Li W., Jia M., Chu M., et al. Risk Factors for severe residual headache in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2021;52:531–536. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palazzo P., Agius P., Ingrand P., Ciron J., Lamy M., Berthomet A., et al. Venous thrombotic recurrence after cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2017;48:321–326. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coutinho J.M., Ferro J.M., Canhão P., Barinagarrementeria F., Cantú C., Bousser M.-G., et al. Cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis in women. Stroke. 2009;40:2356–2361. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson A.E., Anisimowicz Y., Miedema B., Hogg W., Wodchis W.P., Aubrey-Bassler K. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: a QUALICOPC study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:38. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0440-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein P., Shu L., Nguyen T.N., Siegler J.E., Omran S.S., Simpkins A.N., et al. Outcome prediction in cerebral venous thrombosis: the IN-REvASC score. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022;24:404–416. doi: 10.5853/jos.2022.01606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qureshi A.I. A classification scheme for assessing recanalization and collateral formation following cerebral venous thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2010;3:1–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao L., Xu W., Li T., Yu X., Cao S., Xu H., et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance venography in diagnosing cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2018;167:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wetzel S.G., Kirsch E., Stock K.W., Kolbe M., Kaim A., Radue E.W. Cerebral veins: comparative study of CT venography with intraarterial digital subtraction angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:249–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yaghi S., Shu L., Bakradze E., Salehi Omran S., Giles J.A., Amar J.Y., et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis (ACTION-CVT): a multicenter international study. Stroke. 2022;53:728–738. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferro J.M., Coutinho J.M., Dentali F., Kobayashi A., Alasheev A., Canhão P., et al. Safety and efficacy of dabigatran etexilate vs dose-adjusted Warfarin in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:1457–1465. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stolz E., Trittmacher S., Rahimi A., Gerriets T., Röttger C., Siekmann R., et al. Influence of recanalization on outcome in dural sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2004;35:544–547. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000112972.09096.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data, data extraction templates, and analytic code are available on reasonable request.