Abstract

Introduction:

Despite much progress, the prognosis for H3K27-altered diffuse midline glioma (DMG), previously known as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma when located in the brainstem, remains dark and dismal.

Areas covered:

A wealth of research over the past decade has revolutionized our understanding of the molecular basis of DMG, revealing potential targetable vulnerabilities for treatment of this lethal childhood cancer. However, obstacles to successful clinical implementation of novel therapies remain, including effective delivery across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to the tumor site. Here, we review relevant literature and clinical trials and discuss direct drug delivery via convection-enhanced delivery (CED) as a promising treatment modality for DMG. We outline a comprehensive molecular, pharmacological, and procedural approach that may offer hope for afflicted patients and their families.

Expert opinion:

Challenges remain in successful drug delivery to DMG. While CED and other techniques offer a chance to bypass the BBB, the variables influencing successful intratumoral targeting are numerous and complex. We discuss these variables and potential solutions that could lead to the successful clinical implementation of preclinically promising therapeutic agents.

Keywords: Diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27-altered, H3 K27M, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, blood-brain barrier, targeted therapeutics, pharmacokinetics, convection-enhanced delivery

1. Introduction

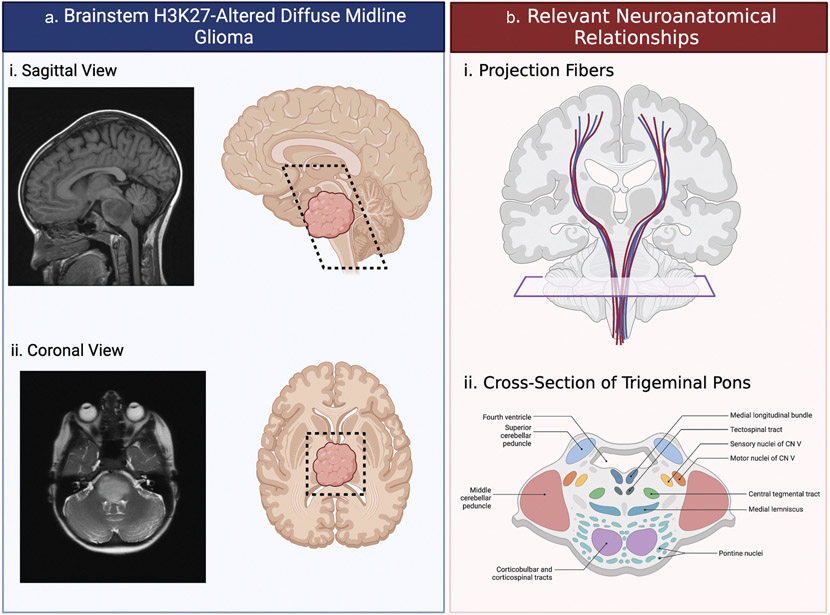

Among pediatric high-grade gliomas, H3K27-altered diffuse midline glioma (DMG), formerly known as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), is associated with an abysmal prognosis and 5-year survival rate (<2%) [1, 2]. About 300 children are diagnosed with brainstem DMG per year in the United States, comprising 10% of all primary pediatric brain tumors and 80% of brainstem tumors in this age group, most commonly in middle childhood (5–10 years old) [1, 3, 4]. Reflective of the anatomical localization and diffusely infiltrative growth pattern (Figure 1a), patients with DMG may present with a wide range of symptoms including headache, nausea, and the triad of cranial nerve dysfunction (i.e. diplopia and facial asymmetry), cerebellar signs (i.e. ataxia and dysmetria), and long-tract signs (i.e. hyperreflexia and paresis) [5, 6]. Obstructive hydrocephalus is a common late manifestation of disease [5, 7].

Figure 1. Location and implicated anatomy of H3K27-altered diffuse midline glioma (DMG).

(a) DMG tumors were traditionally believed to be pontine, as indicated on the (Ai) sagittal T1 and (Aii) axial T2 MRIs. However, improvements in imaging, biopsy and molecular biology revealed these tumors throughout the midline structures including the thalamus, midbrain, pons, medulla, cerebellar peduncles, and cerebellum. These regions (black dashed line) can be appreciated on both sagittal (Ai) and axial (Aii) planes. (b) The diffuse nature of DMG brainstem gliomas has the potential to impact important neurological structures. (Bi) Projection fibers carrying information from the spinal cord must pass through the midline structures to reach the cortex and may be disrupted by tumor infiltration. (Bii) Additionally, cranial nerves and other nuclei located as displayed by the cross-section can be disturbed by the tumor causing malfunction. Figure created in BioRender.com.

Previously, diagnosis of brainstem DMG was made based on characteristic imaging features on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), including diffuse T2-weighted signal with ill-defined margins, occupation of >50% of pontine diameter, and encasement of the basilar artery [5, 8]. More recently, it has been established that DMG has the proclivity to migrate along adjacent midline structures including the thalamus, cerebellar peduncles, and spinal cord [9]. Due to its highly elo-quent location (Figure 1b), any opportunity for meaningful surgical resection of DMG is not possible [10]. The established standard of care for these tumors is radiotherapy, although it is mostly palliative [11, 12]. Many patients ultimately enroll in a clinical trial following radiotherapy, and while there are numerous trials ongoing, perhaps the drug attracting the most attention of late is the DRD2/3 antagonist ONC201, which we will discuss in this Special Report.

Seminal studies over the past decade have revolutionized our understanding of the molecular basis of DMG, revealing potential targets for treatment of this lethal childhood cancer. However, obstacles to successful clinical implementation of novel therapies remain. In this invited review, we discuss direct drug delivery via convection-enhanced delivery (CED) as a promising treatment modality for DMG and outline a comprehensive molecular, pharmacological, and procedural approach that may offer hope for afflicted patients and their families.

2. Molecular features and therapeutic targets

2.1. Molecular features of H3K27-altered DMG

Historically, surgeons and oncologists alike have been reluctant to obtain DMG tissue due to concerns over procedure-associated morbidity [13]. Over the last two decades, multiple neurosurgical groups have demonstrated the safety of image-guided stereotactic biopsy of these tumors, increasing availability of previously scarce tumor specimen for further study [14-17]. Pioneering research of available biopsy and autopsy samples has revealed somatic oncogenic mutations affecting chromatin regulation and has greatly improved our understanding of the unique biology of these tumors. Most DMGs harbor gain-of-function mutations in gene coding for select histone subunit 3 (H3) isoforms, specifically H3F3A and HIST1H3B, encoding histone H3.3 and H3.1, respectively. Most mutations result in a lysine residue substitution for methionine at position 27 of histone H3 (H3K27M) [18-20].

An array of characteristic genetic and epigenetic alterations in pediatric high-grade gliomas including DMG has subsequently been identified in recent years [21-23]. To reflect the practical and conceptual importance of these groundbreaking findings, a new family of tumor types, entitled ‘pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas,’ was added to the 2021 WHO Classification of CNS Tumors, and DMGs are now designated as ‘diffuse midline glioma, H3K27-altered,’ recognizing that non-K27M mutations in these genes exist in a small subset of these tumors [24].

2.2. Epigenetic modifiers

Genome-wide loss of H3K27me3 is a hallmark of H3K27-altered DMG and is believed to result in de-repression of developmental transcriptional programs controlled by bivalent enhancers [25-30]. Preclinical studies using the histone demethylase inhibitor GSKJ4 have demonstrated promising antitumor activity specific to H3K27M-mutant tumors [31, 32]. Histone deacetylase inhibitors such as vorinostat and panobinostat were shown to be effective against multiple DMG cell lines in vitro and at present have moved into clinical trials as both single (NCT03566199) and combination agents (NCT02420613, NCT01189266, NCT04341311, and NCT03632317) [33-35]. While activation of bivalent enhancers is believed to contribute to DMG tumorigenesis, these tumors likewise display a dependency on polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) [36, 37]. A variety of small-molecule inhibitors targeting transcriptional regulators, including the PRC2 methylase EZH2 and bromodomain family proteins, are currently being exploited to identify other actionable epigenetic vulnerabilities [38-40].

2.3. Tyrosine-kinase inhibitors

Additional genetic alterations are common in DMG, including those affecting tumor protein p53 (TP53), platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), activin receptor type 1 (ACVR1), Myc proto-oncogene family members (MYC, MYCN), and others [22, 23, 40]. Drug screens targeting some pathways impacted by these mutations have paved the way for multiple clinical trials, notably involving multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g. dasatinib [NCT02233049, NCT01644773, NCT00996723], ribociclib [NCT03355794, NCT02607124]) and mTOR inhibitors (e.g. everolimus [NCT03355794, NCT05476939, NCT02233049, NCT03632317], temsirolimus [NCT02420613]).

2.3.1. Cell-based therapies

Tumor-specific surface molecules are also being harnessed to transport a cytotoxic payload or cellular therapy to DMG cells while minimizing off-target side effects. B7-H3 has been shown to be overexpressed in the majority of high-grade gliomas, including DMG [41]. In a phase-I clinical trial of the radiolabeled antibody 124I-8H9, which targets B7-H3, the therapy was safe with a promising volume of distribution (Vd) in the targeted area (NCT01502917) [42, 43]. To determine the efficacy and safety of 131I-omburtamab, a B7-H3 antibody conjugated to a different isotope of iodine, Souweidane and colleagues are in the final stages of initiating phase-I/II study for children with DMG that have not progressed following radiation (NCT05063357). Since the early 1990s, the non-canonical IL-13 receptor subunit alpha 2 (IL-13Rα2) has been used in a similar fashion to transport exotoxin chimeric molecules to pediatric and adult high-grade gliomas [44-46]. Heiss et al. recently completed the first phase-I clinical trial of IL13-PE38QQR in DMG with no patient experiencing a dose-limiting toxicity (NCT00088061) [47]. The disialoganglioside GD2 is highly expressed in tumors of neuroectodermal origin, and an anti-GD2 CAR-T study portrayed positive results in DMG in vitro and in vivo models [48]. Recruitment for a first-in-human phase-I clinical trial (NCT04196413) is ongoing, but the authors have reported promising results from the first four patients treated with GD2-directed CAR-T cells [49].

2.3.2. ONC201

Amid a plethora of failed trials, the DRD2 antagonist, ONC201 has coveted much attention as of late. In 2019, a case report detailing tumor regression and facial palsy reversal in a 10 year old patient with brainstem DMG [50]. This sparked a number of clinical trials with ONC201 alone or in combination with radiotherapy and/or additional drugs. Later, in 2019, the same group published the results of the first 14 patients with recurrent H3K27M DMG treated with ONC201 (NCT02525692) where they reported a median progression-free survival of 14 weeks and median overall survival of 17 weeks [51]. Three adult patients remained on therapy with a progression-free follow-up of 49.6 weeks, which might indicate that the adult form of this tumor is more targetable by ONC201 [51]. In a different study, 28 pediatric patients with confirmed H3K27M tumors with treated with a German-sourced ONC201 showed a median overall survival of 18 months and this was increased to 22 months in those who underwent reirradiation [52]. More recently, an open label, multisite trial (NCT03416530) was published and the five patients who had begun ONC201 following radiation and prior to occurrence were still alive 24 months post-diagnosis [53].

There are a number of ongoing ONC201 trials including one study for adults with H3K27M tumors (NCT03295396). There is a large phase III study underway across many institutions for ONC201 following radiotherapy (NCT05580562) as well as two studies looking at ONC201 in combination with everolimus (NCT05476939) and paxalisib (NCT05009992). These studies will hopefully provide insight into the long-term potential of ONC201 as a therapy for H3K27M tumors.

3. Pharmacokinetic determinants

The molecular heterogeneity and anatomical location of DMG present major obstacles to successful translation of preclinical activity of therapeutic candidates into effective anti-tumor therapies in patients, requiring tumor-specific targeting and innovative drug delivery strategies.

Heterogenous therapeutic vulnerabilities among DMG tumors may have contributed to the inadequate efficacy of previous clinical trials [47, 54]. Consistent with this idea, the IL-13Rα2 immunotoxin GB-13 extended survival in a manner strongly associated with target receptor expression in adult glioblastoma and DMG animal models [55] and the results seen in the original ONC201 trial [51]. Furthermore, intratumoral heterogeneity has been found to be a major contributor to drug resistance and differing therapeutic responses [56, 57]. These observations call into question the value of locally restricted fine-needle biopsy sampling and highlight the need for more rigorous biological-based trial inclusion criteria.

A critical determinant of drug efficacy is achieving adequate exposure of an active agent at its site of action (i.e. effective concentrations of drug in its active, unbound form present at the tumor site for a long enough period of time). Restricted systemic drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS) is most frequently attributed to the blood–brain barrier (BBB). This complex neurovascular unit excludes nearly all macromolecules and most small molecules from extravagating into the brain parenchyma [58, 59]. In the case of DMG, the absence of contrast-enhancement is indicative of a largely intact BBB [60]. Preclinical evidence further suggests that the brainstem may have a lower density of capillaries than cortical regions and is home to an even more robust BBB, additionally increasing the level of difficulty in delivering therapeutic payloads systemically [61, 62]. Application of CNS pharmacokinetics is therefore critical to the design of new drug formulations and mechanisms of drug delivery, which must be specifically engineered with the aim of optimizing therapeutic exposure at the tumor site in order to impart therapeutic effect.

Attempts to manipulate the BBB and optimize drug delivery to their sites of action have led to the development of noninvasive and invasive administration techniques [63-65]. Osmotic disruption with mannitol, microbubble-mediated focused ultrasound, and pharmacologic manipulation by bradykinin and its agonists enable transport of a wide range of therapeutics to the CNS, but their effects are transient and nonspecific [66-68]. Invasive strategies such as biodegradable polymers, osmotic pumps, and intrathecal or intraventricular injection facilitate administration directly into the cerebrospinal fluid or brain parenchyma, thereby minimizing toxicities associated with systemic exposure [69, 70]. However, drug distribution and dispersion are limited by the principles of diffusion [59, 71]. Direct loco-regional perfusion of brain parenchyma using a small hydrostatic pressure gradient relies primarily on bulk flow to distribute infusates (i.e. a pressure gradient rather than a concentration gradient) [72]. This technology has been termed convection-enhanced delivery (CED) and is becoming more widely used in research models and clinical trials of DMG.

4. Convection-enhanced delivery

CED is a surgical technique that has gained traction as a promising method that addresses the key problem of low drug penetration and residence time in DMG [73]. CED involves placement of one or multiple catheters directly into the tumor, which may be implanted at the time of biopsy, thus bypassing the BBB and allowing for prolonged administration of infusates into the tumor mass [10, 74] (Figure 2a). The technical capabilities and limitations of CED have been explored by multiple groups and are well characterized [74-77]. Pharmacokinetic studies in both small- and large-animal models have demonstrated that nano-scale particles with a diameter of less than 100 nm are the ideal size for achieving a large Vd per volume of infusion but are readily cleared by efflux mechanisms [78–81]. Hydrophobic and positively charged molecules tend to have a poor Vd [80, 82, 83], while surface modification of drugs has been shown to improve Vd and facilitate tumor specificity [42, 80, 84]. CED-paired nanoparticles allow hydrophobic drugs to traverse the extracellular space, facilitate controlled release of drug over time, and prevent premature drug degradation [85, 86]. Two clinical trials of panobinostat in patients with newly diagnosed DMG are currently underway using such a formulation (MTX110; NCT03566199, NCT04264143).

Figure 2. Implications for direct intratumoral targeting of H3K27-altered diffuse midline glioma.

(a) The delicate location within the brainstem and intact blood–brain-barrier (BBB) eliminates surgical intervention and limits systemic therapeutic efficacy. Delivering therapy directly to the brainstem tumor via an implanted catheter has the potential to enhance therapeutic benefit. (b) The variable impacting the potential success of intratumoral targeting are complex and multifold. First, targeted therapies with significant therapeutic potential must be identified by in vitro drug screens and dose-response analysis. Furthermore, intratumoral targeting is dependent on inherent physicochemical properties of the drug itself such as solubility, lipophilicity, molecular and/or the physicochemical properties of the drug packaging, like a nanoparticle. Finally, successful delivery will require optimization of the delivery technique itself. This might include such things as infusion rate, catheter design, or trajectory planning. Figure created in BioRender.com.

CED has been proven safe in multiple clinical studies of malignant brain tumors including DMG [42, 43, 47, 75, 77, 87, 88]; however, a myriad of variables ought to be considered in developing an effective CED platform. Catheter configuration, design, and positioning; the number of catheters employed; as well as the infusion duration, flow rate, and volume remain areas of ongoing investigation [69, 89].

While traditional end-port cannulae have been most commonly used, improved infusion profiles have been observed with recessed step catheters and those with a porous tip [90-93]. In the largest clinical trial of CED for high-grade glioma, post-hoc MRI analysis revealed that only half of the catheters were adequately placed in the targeted area [54, 88]. Software algorithms to model and estimate infusion distribution based on the planned catheter trajectory, infusion parameters, and patient/tumor-specific anatomy are being developed in an effort to address this shortcoming. For example, Wembacher-Schroeder et al. compared the distribution of a radiolabeled antibody as determined by positron emission tomography (PET) to the distribution estimated by the iPlan Flow simulation algorithm, and found acceptable similarity in 8 out of 10 patients [94]. Use of robotic guidance to improve the accuracy of catheter placement was shown to be feasible to stereotactically implant a CED catheter in a 5-year-old patient with a large brainstem DMG [95].

Barua et al. developed a bone-anchored port system that can be connected to multiple-catheters (up to four catheters) and facilitates repeated CED administration to the brain without requiring multiple surgeries [96, 97]. Chronic, continuous CED via an implantable subcutaneous pump has been tested extensively in small and large animal models for up to 32 days of uninterrupted infusion [98-101]. This system has recently been used in DMG patients to safely deliver two 48-hour-infusions of MTX110 7 days apart [102].

Most studies to date have relied on gadolinium-based contrast agents as a surrogate tracer to track infusate distribution over time. Gadolinium (Gd) formulations are available at a large range of molecular weights and have been shown to accurately track the distribution of IL13-PE38QQR at certain concentrations [91, 103, 104]. However, the hydrophilic nature of most Gd formulations is likely to lead to a different distribution pattern than most small-molecule drugs and chemotherapeutic agents used with CED [59, 82]. Furthermore, drug-specific physicochemical properties, which may cause metabolic breakdown or tissue binding depending on the duration of infusion, differ from inert tracers and, consequently, impact surrogate imaging accuracy over time [104].

5. Expert opinion

A wealth of research over the past decade has revealed multiple targetable vulnerabilities in DMG, but effective drug delivery to the tumor remains a central obstacle to improving patient outcomes. Numerous drug screens in patient-derived cell lines and patient-derived xenografts have identified molecular dependencies and promising treatments, yet considerable systemic toxicity and a low BBB penetrance in the brainstem limit translation of these findings to the clinic [59]. Direct drug delivery via CED is a promising method to address these limitations but is constrained by intrinsic physicochemical properties of the infusate and the brainstem microenvironment, which impact tumor targeting, distribution volume, and drug elimination from the brain. Finding the right drug, getting it to the tumor, and then keeping it there long enough is likely what it is going to take (Figure 2b).

While CED allows for small molecules to cover larger tumor volumes in animal models, they are more rapidly cleared from the brainstem [81, 101]. Conversely, larger therapeutics have been shown to be limited in terms of their interstitial distribution, due to spatial and steric hindrance and interaction with cell surface/extracellular molecules, but may reside at the tumor site for longer periods following loco-regional infusion [78]. Future studies must address these pharmacokinetic principles when considering translatability of potential therapeutics.

Drugs that have known efficacy in drug screens and that possess chemical handles allowing for simple chemical modification can be used to modify their structure to create drug ‘depots’ to allow sustained delivery following direct delivery [105]. Further development and evaluation of the safety, distribution, and clearance effects of different molecular weight polyethylene glycol and boron-dextran complexes when directly delivered to the brainstem will assess the prospects of this approach. Furthermore, the effects of blocking efflux pumps on drug clearance may be analyzed for DMG [106, 107].

An alternative approach to optimize tumor-coverage and achieve longer sustained drug delivery when administered directly to the brain is to modify nanoparticle formulations for CED. Various nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems have caught the attention of researchers worldwide, encouraging the field to rapidly develop improved ways for effective drug delivery across the BBB [108]. Nanoparticles can be loaded with drugs and tuned to protect and release drug over extended periods of time [109, 110]. Additionally, co-loading with imaging agents like Gd can be used to visualize in real-time the volume of distribution when directly administered to the brain [111, 112]. Optimization of nanoparticle loading and release with several preclinical drug hits and contrast agent as well as in vivo pharmacokinetic studies will be required to evaluate direct nanoparticle delivery and clearance from the brainstem.

In sum, extensive research efforts have revealed a central role for epigenetic dysregulation in the pathogenesis of DMG. Clinically, standard fractionated radiotherapy to a dose of 54–59 Gy over 30 fractions remains the mainstay of treatment for newly diagnosed DMG, which alleviates some symptoms for a short period of time without providing a significant improvement in overall survival [113]. Over 100 clinical trials with therapeutics have yet to find benefit [11].

Moving forward, the next generation of therapeutic approaches should implement recent groundbreaking findings in the fields of DMG biology and CNS pharmacokinetics into clinically efficacious treatments for this intractable disease.

Article highlights.

H3K27-altered diffuse midline glioma (DMG) is a rare but deadly brain tumor predominately found in children.

Despite decades of research, clinicians have not yet been able to overcome the complex obstacles for successful clinical implementation of novel therapies.

While some therapies may be limited by intratumoral heterogeneity or lack of sufficient exposure time, the crux in almost all therapies is the blood–brain-barrier (BBB).

To circumvent the BBB, convection-enhanced delivery (CED) has emerged as a safe technique to deliver drugs directly into the tumor with additional optimization currently underway in preclinical and clinical studies.

A successful therapy for DMG tumors will likely require that we are able to get a cytotoxic drug to the tumor and keep it there for long enough to elicit its effects.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. No financial or material support was received for this research or the creation of this work.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Waite K, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2014–2018. Neuro Oncol. 2021. Oct 5;23 (12Suppl 2):iii1–iii105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren KE. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: poised for progress. Front Oncol. 2012;2:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaimes C, Poussaint TY. Primary neoplasms of the pediatric brain. Radiol Clin North Am. 2019. Nov;57(6):1163–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MA, Freidlin B, Ries LA, et al. Trends in reported incidence of primary malignant brain tumors in children in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998. Sep 2;90(17):1269–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen KJ, Jabado N, Grill J. Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas-current management and new biologic insights. Is there a glimmer of hope? Neuro Oncol. 2017. Aug 1;19(8):1025–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albright AL, Guthkelch AN, Packer RJ, et al. Prognostic factors in pediatric brain-stem gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1986. Dec;65(6):751–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshimura J, Onda K, Tanaka R, et al. Clinicopathological study of diffuse type brainstem gliomas: analysis of 40 autopsy cases. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2003. Aug;43(8):375–382. discussion 382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein F, Constantini S. Practical decisions in the treatment of pediatric brain stem tumors. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1996;24(1):24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gururangan S, McLaughlin CA, Brashears J, et al. Incidence and patterns of neuraxis metastases in children with diffuse pontine glioma. J Neurooncol. 2006. Apr;77(2):207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Himes BT, Zhang L, Daniels DJ. Treatment strategies in diffuse midline gliomas with the H3K27M mutation: the role of convection-enhanced delivery in overcoming anatomic challenges. Front Oncol. 2019;9:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rechberger JS, Lu VM, Zhang L, et al. Clinical trials for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: the current state of affairs. Childs Nerv Syst. 2020. Jan;36(1):39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frazier JL, Lee J, Thomale UW, et al. Treatment of diffuse intrinsic brainstem gliomas: failed approaches and future strategies. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009. Apr;3(4):259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker DA, Liu J, Kieran M, et al. A multi-disciplinary consensus statement concerning surgical approaches to low-grade, high-grade astrocytomas and diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas in childhood (CPN Paris 2011) using the Delphi method. Neuro Oncol. 2013. Apr;15(4):462–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roujeau T, Machado G, Garnett MR, et al. Stereotactic biopsy of diffuse pontine lesions in children. J Neurosurg. 2007. Jul;107(1 Suppl):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawes W, Marcus HJ, Tisdall M, et al. Robot-assisted stereotactic brainstem biopsy in children: prospective cohort study. J Robot Surg. 2019. Aug;13(4):575–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamisch C, Kickingereder P, Fischer M, et al. Update on the diagnostic value and safety of stereotactic biopsy for pediatric brain-stem tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 735 cases. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017. Sep;20(3):261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams JR, Young CC, Vitanza NA, et al. Progress in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: advocating for stereotactic biopsy in the standard of care. Neurosurg Focus. 2020. Jan 1;48(1):E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, et al. Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brain-stem glioblastomas. Nat Genet. 2012. Jan 29;44(3):251–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• One of two seminal 2012 studies that identified somatic histone H3 alterations as driver mutations in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, et al. Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature. 2012. Jan 29;482(7384):226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• One of two landmark 2012 manuscripts detailing recurrent mutations in a regulatory histone gene and subsequent defects of the chromatin architecture in paediatric and young adult glioblastoma pathogenesis. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khuong-Quang DA, Buczkowicz P, Rakopoulos P, et al. K27M mutation in histone H3.3 defines clinically and biologically distinct subgroups of pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2012. Sep;124(3):439–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saratsis AM, Kambhampati M, Snyder K, et al. Comparative multi-dimensional molecular analyses of pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma reveals distinct molecular subtypes. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(6):881–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lulla RR, Saratsis AM, Hashizume R. Mutations in chromatin machinery and pediatric high-grade glioma. Sci Adv. 2016. Mar;2 (3):e1501354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones C, Karajannis MA, Jones DTW, et al. Pediatric high-grade glioma: biologically and clinically in need of new thinking. Neuro Oncol. 2017. Feb 1;19(2):153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021. Aug 2;23(8):1231–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A review of the 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System, summarizing the major changes in the fifth edition classification and the specific changes in each taxonomic category, including pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas, as well as highlighting the advanced role of molecular diagnostics in contemporary CNS tumor classification. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis PW, Muller MM, Koletsky MS, et al. Inhibition of PRC2 activity by a gain-of-function H3 mutation found in pediatric glioblastoma. Science. 2013. May 17;340(6134):857–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan KM, Fang D, Gan H, et al. The histone H3.3K27M mutation in pediatric glioma reprograms H3K27 methylation and gene expression. Genes Dev. 2013. May 1;27(9):985–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bender S, Tang Y, Lindroth AM, et al. Reduced H3K27me3 and DNA hypomethylation are major drivers of gene expression in K27M mutant pediatric high-grade gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2013. Nov 11;24 (5):660–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venneti S, Garimella MT, Sullivan LM, et al. Evaluation of histone 3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and enhancer of Zest 2 (EZH2) in pediatric glial and glioneuronal tumors shows decreased H3K27me3 in H3F3A K27M mutant glioblastomas. Brain Pathol. 2013. Sep;23(5):558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krug B, De Jay N, Harutyunyan AS, et al. Pervasive H3K27 acetylation leads to ERV expression and a therapeutic vulnerability in H3K27M gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2019. May 13;35(5):782–797.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson JD, Kasper LH, Paugh BS, et al. Histone H3.3 K27M accelerates spontaneous brainstem glioma and drives restricted changes in bivalent gene expression. Cancer Cell. 2019. Jan 14;35(1):140–155.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruidenier L, Chung CW, Cheng Z, et al. A selective jumonji H3K27 demethylase inhibitor modulates the proinflammatory macrophage response. Nature. 2012. Aug 16;488(7411):404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hashizume R, Andor N, Ihara Y, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of histone demethylation as a therapy for pediatric brainstem glioma. Nat Med. 2014. Dec;20(12):1394–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown ZZ, Müller MM, Jain SU, et al. Strategy for “detoxification” of a cancer-derived histone mutant based on mapping its interaction with the methyltransferase PRC2. J Am Chem Soc. 2014. Oct 1;136(39):13498–13501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grasso CS, Tang Y, Truffaux N, et al. Functionally defined therapeutic targets in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Nat Med. 2015. Jun;21(6):555–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitanza NA, Biery MC, Myers C, et al. Optimal therapeutic targeting by HDAC inhibition in biopsy-derived treatment-naïve diffuse midline glioma models. Neuro Oncol. 2021. Mar 25;23(3):376–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohammad F, Weissmann S, Leblanc B, et al. EZH2 is a potential therapeutic target for H3K27M-mutant pediatric gliomas. Nat Med. 2017. Apr;23(4):483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lavarone E, Barbieri CM, Pasini D. Dissecting the role of H3K27 acetylation and methylation in PRC2 mediated control of cellular identity. Nat Commun. 2019. Apr 11;10(1):1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Dong W, Zhu J, et al. Combination of EZH2 inhibitor and BET inhibitor for treatment of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Cell Biosci. 2017;7:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piunti A, Hashizume R, Morgan MA, et al. Therapeutic targeting of polycomb and BET bromodomain proteins in diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Nat Med. 2017. Apr;23(4):493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Argersinger DP, Rivas SR, Shah AH, et al. New developments in the pathogenesis, therapeutic targeting, and treatment of H3K27M-mutant diffuse midline glioma. Cancers (Basel). 2021. Oct;13(21):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Z, Luther N, Ibrahim GM, et al. B7-H3, a potential therapeutic target, is expressed in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J Neurooncol. 2013. Feb;111(3):257–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Souweidane MM, Kramer K, Pandit-Taskar N, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: a single-centre, dose-escalation, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018. Aug;19(8):1040–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bander ED, Ramos AD, Wembacher-Schroeder E, et al. Repeat convection-enhanced delivery for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2020;25:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Debinski W, Gibo DM, Hulet SW, et al. Receptor for interleukin 13 is a marker and therapeutic target for human high-grade gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1999. 5;May(5):985–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Debinski W, Obiri NI, Pastan I, et al. A novel chimeric protein composed of interleukin 13 and Pseudomonas exotoxin is highly cytotoxic to human carcinoma cells expressing receptors for interleukin 13 and interleukin 4. J Biol Chem. 1995. Jul 14;270(28):16775–16780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Debinski W, Obiri NI, Powers SK, et al. Human glioma cells overexpress receptors for interleukin 13 and are extremely sensitive to a novel chimeric protein composed of interleukin 13 and pseudomonas exotoxin. Clin Cancer Res. 1995. Nov;1(11):1253–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heiss JD, Jamshidi A, Shah S, et al. Phase I trial of convection-enhanced delivery of IL13-Pseudomonas toxin in children with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2018. Dec 7;23(3):333–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mount CW, Majzner RG, Sundaresh S, et al. Potent antitumor efficacy of anti-GD2 CAR T cells in H3-K27M(+) diffuse midline gliomas. Nat Med. 2018. May;24(5):572–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Majzner RG, Ramakrishna S, Yeom KW, et al. GD2-CAR T cell therapy for H3K27M-mutated diffuse midline gliomas. Nature. 2022. Mar;603(7903):934–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Recent report of the first four DMG patients in a first-in-human phase I clinical trial of GD2-directed CAR T cells, demonstrating early promise of this therapeutic approach. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall MD, Odia Y, Allen JE, et al. First clinical experience with DRD2/3 antagonist ONC201 in H3 K27M-mutant pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: a case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019. Apr 5;23(6):719–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Important study first introducing clinical results with ONC201. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chi AS, Tarapore RS, Hall MD, et al. Pediatric and adult H3 K27M-mutant diffuse midline glioma treated with the selective DRD2 antagonist ONC201. J Neurooncol. 2019. Oct;145(1):97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duchatel RJ, Mannan A, Woldu AS, et al. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of German-sourced ONC201 for the treatment of H3K27M-mutant diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Neurooncol Adv. 2021. January-December;3(1):vdab169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gardner SL, Tarapore RS, Allen J, et al. Phase I dose escalation and expansion trial of single agent ONC201 in pediatric diffuse midline gliomas following radiotherapy. Neurooncol Adv. 2022. January-December;4(1):vdac143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mueller S, Polley MY, Lee B, et al. Effect of imaging and catheter characteristics on clinical outcome for patients in the PRECISE study. J Neurooncol. 2011. Jan;101(2):267–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rechberger JS, Porath KA, Zhang L, et al. IL-13Rα2 status predicts GB-13 (IL13.E13K-PE4E) efficacy in high-grade glioma. Pharmaceutics. 2022. Apr 24;14(5):922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saunders NA, Simpson F, Thompson EW, et al. Role of intratumoural heterogeneity in cancer drug resistance: molecular and clinical perspectives. EMBO Mol Med. 2012. Aug;4(8):675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greene JM, Levy D, Fung KL, et al. Modeling intrinsic heterogeneity and growth of cancer cells. J Theor Biol. 2015. Feb;21(367):262–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005. Jan;2(1):3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Warren KE. Beyond the blood:brain barrier: the importance of Central Nervous System (CNS) pharmacokinetics for the treatment of CNS tumors, including diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Front Oncol. 2018;8:239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bailey S, Howman A, Wheatley K, et al. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma treated with prolonged temozolomide and radiotherapy–results of a United Kingdom phase II trial (CNS 2007 04). Eur J Cancer. 2013. Dec;49(18):3856–3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Subashi E, Cordero FJ, Halvorson KG, et al. Tumor location, but not H3.3K27M, significantly influences the blood-brain-barrier permeability in a genetic mouse model of pediatric high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2016. Jan;126(2):243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao R, Pollack GM. Regional differences in capillary density, perfusion rate, and P-glycoprotein activity: a quantitative analysis of regional drug exposure in the brain. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009. Oct 15;78(8):1052–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.El-Khouly FE, van Vuurden DG, Stroink T, et al. Effective drug delivery in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: a theoretical model to identify potential candidates. Front Oncol. 2017;7:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Griffith JI, Rathi S, Zhang W, et al. Addressing BBB Heterogeneity: a new paradigm for drug delivery to brain tumors. Pharmaceutics. 2020. Dec 11;12(12)1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Power EA, Rechberger JS, Gupta S, et al. Drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier for the treatment of pediatric brain tumors - An update. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;185:114303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bartus RT, Elliott P, Hayward N, et al. Permeability of the blood brain barrier by the bradykinin agonist, RMP-7: evidence for a sensitive, auto-regulated, receptor-mediated system. Immunopharmacology. 1996. Jun;33(1–3):270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Englander ZK, Wei HJ, Pouliopoulos AN, et al. Focused ultrasound mediated blood-brain barrier opening is safe and feasible in a murine pontine glioma model. Sci Rep. 2021. Mar 22;11(1):6521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCrea HJ, Ivanidze J, O’Connor A, et al. Intraarterial delivery of bevacizumab and cetuximab utilizing blood-brain barrier disruption in children with high-grade glioma and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: results of a phase I trial. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2021;6:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kunigelis KE, Vogelbaum MA. Therapeutic delivery to central nervous system. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2021. Apr;32(2):291–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drapeau A, Fortin D. Chemotherapy delivery strategies to the central nervous system: neither optional nor superfluous. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2015;15(9):752–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patel JP, Spiller SE, Barker ED. Drug penetration in pediatric brain tumors: challenges and opportunities. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021. Mar 15:e28983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jagannathan J, Walbridge S, Butman JA, et al. Effect of ependymal and pial surfaces on convection-enhanced delivery. J Neurosurg. 2008. Sep;109(3):547–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bobo RH, Laske DW, Akbasak A, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of macromolecules in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994. Mar 15;91(6):2076–2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Important study first introducing the concept of convection-enhanced delivery. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lonser RR, Sarntinoranont M, Morrison PF, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery to the central nervous system. J Neurosurg. 2015. Mar;122(3):697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vogelbaum MA, Sampson JH, Kunwar S, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of cintredekin besudotox (interleukin-13-PE38QQR) followed by radiation therapy with and without temozolomide in newly diagnosed malignant gliomas: phase 1 study of final safety results. Neurosurgery. 2007. Nov;61(5):1031–1037. discussion 1037–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou Z, Singh R, Souweidane MM. Convection-enhanced delivery for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma treatment. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(1):116–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morgenstern PF, Zhou Z, Wembacher-Schröder E, et al. Clinical tolerance of corticospinal tracts in convection-enhanced delivery to the brainstem. J Neurosurg. 2018. Dec 21;131(6):1812–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rechberger JS, Power EA, Lu VM, et al. Evaluating infusate parameters for direct drug delivery to the brainstem: a comparative study of convection-enhanced delivery versus osmotic pump delivery. Neurosurg Focus. 2020. Jan 1;48(1):E2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sampson JH, Brady ML, Petry NA, et al. Intracerebral infusate distribution by convection-enhanced delivery in humans with malignant gliomas: descriptive effects of target anatomy and catheter positioning. Neurosurgery. 2007. Feb;60(2Suppl 1):ONS89–98. discussion ONS98–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Allard E, Passirani C, Benoit JP. Convection-enhanced delivery of nanocarriers for the treatment of brain tumors. Biomaterials. 2009. Apr;30(12):2302–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Singleton WGB, Bienemann AS, Woolley M, et al. The distribution, clearance, and brainstem toxicity of panobinostat administered by convection-enhanced delivery. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2018. Sep;22 (3):288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen MY, Hoffer A, Morrison PF, et al. Surface properties, more than size, limiting convective distribution of virus-sized particles and viruses in the central nervous system. J Neurosurg. 2005. Aug;103(2):311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Healy AT, Vogelbaum MA. Convection-enhanced drug delivery for gliomas. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6(Suppl 1):S59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luther N, Zhou Z, Zanzonico P, et al. The potential of theragnostic 124I-8H9 convection-enhanced delivery in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2014. Jun;16(6):800–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Louis N, Liu S, He X, et al. New therapeutic approaches for brainstem tumors: a comparison of delivery routes using nanoliposomal irinotecan in an animal model. J Neurooncol. 2018. Feb;136(3):475–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sandberg DI, Kharas N, Yu B, et al. High-dose MTX110 (soluble panobinostat) safely administered into the fourth ventricle in a nonhuman primate model. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2020. May 1;26(1) :127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kunwar S, Prados MD, Chang SM, et al. Direct intracerebral delivery of cintredekin besudotox (IL13-PE38QQR) in recurrent malignant glioma: a report by the cintredekin besudotox intraparenchymal study group. J Clin Oncol. 2007. Mar 1;25(7):837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kunwar S, Chang S, Westphal M, et al. Phase III randomized trial of CED of IL13-PE38QQR vs Gliadel wafers for recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2010. Aug;12(8):871–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The first and, thus far, only phase III clinical trial of CED for malignant brain tumors, comparing the IL-13 immunotoxin Cintredekin Besudotox with intraparenchymally placed Gliadel wafers. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ivasyk I, Morgenstern PF, Wembacher-Schroeder E, et al. Influence of an intratumoral cyst on drug distribution by convection-enhanced delivery: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017. Sep;20(1):256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brady ML, Raghavan R, Mata J, et al. Large-volume infusions into the brain: a comparative study of catheter designs. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2018;96(3):135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brady ML, Grondin R, Zhang Z, et al. In-vitro and in-vivo performance studies of a porous infusion catheter designed for intraparenchymal delivery of therapeutic agents of varying size. J Neurosci Methods. 2022. Aug;1(378):109643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lewis O, Woolley M, Johnson D, et al. Chronic, intermittent convection-enhanced delivery devices. J Neurosci Methods. 2016. Feb;1(259):47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lewis O, Woolley M, Johnson DE, et al. Maximising coverage of brain structures using controlled reflux, convection-enhanced delivery and the recessed step catheter. J Neurosci Methods. 2018. Oct;1(308):337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wembacher-Schroeder E, Kerstein N, Bander ED, et al. Evaluation of a patient-specific algorithm for predicting distribution for convection-enhanced drug delivery into the brainstem of patients with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2021;14:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barua NU, Lowis SP, Woolley M, et al. Robot-guided convection-enhanced delivery of carboplatin for advanced brainstem glioma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013. Aug;155(8):1459–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barua NU, Woolley M, Bienemann AS, et al. Intermittent convection-enhanced delivery to the brain through a novel transcutaneous bone-anchored port. J Neurosci Methods. 2013. Apr 15;214(2):223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barua NU, Hopkins K, Woolley M, et al. A novel implantable catheter system with transcutaneous port for intermittent convection-enhanced delivery of carboplatin for recurrent glioblastoma. Drug Deliv. 2016;23(1):167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lopez KA, Tannenbaum AM, Assanah MC, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of topotecan into a PDGF-driven model of glioblastoma prolongs survival and ablates both tumor-initiating cells and recruited glial progenitors. Cancer Res. 2011. Jun 1;71 (11):3963–3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sonabend AM, Stuart RM, Yun J, et al. Prolonged intracerebral convection-enhanced delivery of topotecan with a subcutaneously implantable infusion pump. Neuro Oncol. 2011. Aug;13(8):886–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.D’Amico RS, Neira JA, Yun J, et al. Validation of an effective implantable pump-infusion system for chronic convection-enhanced delivery of intracerebral topotecan in a large animal model. J Neurosurg. 2019;2:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Occhiogrosso G, Edgar MA, Sandberg DI, et al. Prolonged convection-enhanced delivery into the rat brainstem. Neurosurgery. 2003. Feb;52(2):388–393. discussion 393–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zacharoulis S, Szalontay L, CreveCoeur T, et al. DDEL-07. A Phase I study examining the feasibility of intermittent convection-enhanced delivery (CED) of MTX110 for the treatment of children with newly diagnosed diffuse midline gliomas (DMGs). Neuro Oncol. 2022;24(Supplement_1):i35–i35. [Google Scholar]; •• Recent study demonstrating the feasibility of repeated loco-regional therapeutic MTX110 infusion using CED in patients of newly diagnosed DMG. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Asthagiri AR, Walbridge S, Heiss JD, et al. Effect of concentration on the accuracy of convective imaging distribution of a gadolinium-based surrogate tracer. J Neurosurg. 2011. Sep;115(3):467–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chittiboina P, Heiss JD, Warren KE, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging properties of convective delivery in diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014. Mar;13(3):276–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Park EJ, Choi J, Lee KC, et al. Emerging PEGylated non-biologic drugs. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2019. Jun;24(2):107–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Oberoi RK, Mittapalli RK, Elmquist WF. Pharmacokinetic assessment of efflux transport in sunitinib distribution to the brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013. Dec;347(3):755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gampa G, Kenchappa RS, Mohammad AS, et al. Enhancing brain retention of a KIF11 inhibitor significantly improves its efficacy in a mouse model of glioblastoma. Sci Rep. 2020. Apr 16;10 (1):6524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Koog L, Gandek TB, Nagelkerke A. Liposomes and extracellular vesicles as drug delivery systems: a comparison of composition, pharmacokinetics, and functionalization. Adv Healthc Mater. 2022. March 01;11(5):2100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Song E, Gaudin A, King AR, et al. Surface chemistry governs cellular tropism of nanoparticles in the brain. Nat Commun. 2017. May;19(8):15322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen EM, Quijano AR, Seo YE, et al. Biodegradable PEG-polω-pentadecalactone-co-p-dioxanone) nanoparticles for enhanced and sustained drug delivery to treat brain tumors. Biomaterials. 2018;178:193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Panahi Y, Farshbaf M, Mohammadhosseini M, et al. Recent advances on liposomal nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2017. Jun;45(4):788–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Antimisiaris SG, Mourtas S, Marazioti A. Exosomes and exosome-inspired vesicles for targeted drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2018. Nov 6;10:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gallitto M, Lazarev S, Wasserman I, et al. Role of radiation therapy in the management of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: a systematic review. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2019. July-September;4(3):520–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]