Abstract

Studies have shown associations among stigma, loneliness, and depressive symptoms in older persons living with HIV (PWH) but research assessing the mediating pathway among these variables is sparse. Building on this prior work, the aim of this study was to test the mediating effects of loneliness. A sample of 146 older PWH (≥50 years old) from an out-patient HIV clinic in Atlanta, GA, completed a cross-sectional survey. Mediation analysis, guided by Baron and Kenny’s criteria, was conducted using Stata v14.2 to assess the direct and indirect effects of loneliness on the association between stigma and depressive symptoms while controlling for covariates (sex; income; self-rated health; past unstable housing). Loneliness mediated the association between stigma and depressive symptoms. Stigma predicted higher loneliness, which in turn predicted more depressive symptoms. Findings suggest that addressing depressive symptoms in older PWH may require multifaceted interventions targeting psychosocial and interpersonal factors including stigma and loneliness.

Keywords: Loneliness, Stigma, HIV, Depressive symptoms, Older adults

Introduction

Depression is highly prevalent among persons living with HIV (PWH) [1, 2] and is the most common neuropsychiatric comorbidity along with substance use. Although estimates vary, rates of depression are 2 to 3 times higher among PWH than in the general population [1–4] and depression is known to negatively affect progression of HIV disease [5]. Depression may be more common in persons 65 + years of age, although this is perhaps due to increasing physical and mental comorbidities rather than an independent effect of aging [6]. Aging with HIV is associated with burden of multimorbidity and polypharmacy which may make older PWH especially susceptible to symptoms of depression [7].

HIV-related stigma is commonly experienced by PWH and may partially contribute to higher rates of depression [8, 9] and both are often tied to substance use and non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) [9–11], which can ultimately lead to unsuppressed viral load, poor health, and possible HIV transmission. Moreover, depression and stigma are related to social isolation and to reduced seeking of social support due to fear of rejection and increased feelings of loneliness [12]. A study assessed the relative contribution of stigma, loneliness, and perceived health on clinically relevant symptoms of depression among PWH 50 + years old using the ROAH cohort and found that, controlling for physical health, both HIV-stigma and loneliness contributed significantly and independently, to major depressive symptoms [13]. Similarly, depression and internalized HIV stigma explained a meaningful amount of variance (41%) in loneliness, above that explained by disease status and unstable housing in another cross-sectional study [14]. Research to date suggests that HIV-related stigma, symptoms of depression, and loneliness are highly related and tend to co-occur.

In order to improve intervention strategies to alleviate stigma, depression and loneliness – and eventually, related downstream health consequences – research to disentangle mechanistic contributors is needed. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to assess the relationship of HIV stigma and depression and whether loneliness mediated this relationship. This study builds logically on the prior work in previous research [13, 14] that has shown significant associations among HIV-related stigma, depressive symptoms, and loneliness.

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of a cross-sectional study that assessed the effect of psychosocial factors on retention in HIV care among older PWH. The parent study collected survey data at a one-time visit and was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board and the recruiting clinic’s Research Oversight Committee.

Participants and Data Collection

A sample of older PWH were recruited from a university-affiliated outpatient HIV clinic in Atlanta, GA from 2016 to 2017. Participants were recruited through flyers, word of mouth, and healthcare provider referrals. Eligible individuals were 50 years old or older, living with HIV, and had at least one medical visit established in the recruiting clinic. Eligible individuals completed the informed consent process. Since the study sample was at risk for low literacy, a consent post-test was administered after reviewing the informed consent document with a trained research staff. The post-test assessed participant’s understanding of the study procedures, including risks and benefits, and their ability to give consent. Failure to pass the post-test after three attempts resulted in exclusion from the study (n = 3). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Research staff were available during the survey administration to accommodate participants in completing the survey items on the computer. Total time to complete the survey was approximately 45–60 min. Participants were compensated $25 for their participation.

Measures

HIV-related Stigma—

Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale [15] contains six items that are rated dichotomously (1=“agree”, 0=“disagree”), with scores ranging from 0 to 6. A higher score indicates greater HIV-related stigma. This scale shows good internal reliability (α = 0.73 to 0.76) and criterion validity. The Cronbach’s alpha for our sample was 0.83.

Loneliness—

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)-Social Isolation (SI) Short Form v2.0 8a was used to assess loneliness. This scale uses 8-items that are derived from social relationship scales and the UCLA-Loneliness Scale [16] on a 5-point Likert scale (1=“Never” to 5=“Always”). Following the score conversion table in the scoring instruction, the total raw scores were converted into a standardized T-score with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10. Hence, a T-score of 50 represents an average score and a T-score of 60 represents one SD higher score of loneliness than the average persons in the United States [17]. Cronbach’s alpha for our sample was 0.95.

Depressive Symptoms—

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R) [18] was used to measure depressive symptoms. The CESD-R contains 20 items that assess nine symptoms of depression (dysphoria, anhedonia, appetite, sleep, concentration, worthlessness, fatigue, agitation, and suicidal ideation) in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V) diagnostic criteria for Major Depressive Disorder. Participants answer 0= “Not at all or less than one day” to 3= “Nearly every day for 2 weeks,” with possible scores ranging from 0 to 60. A score ≥ 16 indicates at risk for clinical depression. The scale has good validity and internal consistency [19]. Cronbach’s alpha for our sample was 0.93.

Covariates were selected based on previous findings that suggest an association with depressive symptoms in PWH. Self-reported demographic data on age, race (African American or Black; White; Asian; Alaska Native or American Indian; Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; Multiracial; Other), sex assigned at birth (born male; born female; I choose not to answer), sexual orientation (homosexual, gay, or lesbian; heterosexual or straight; a man who has sex with men; bisexual; other; I choose not to answer), education (never attended school; grades 1 through 8; grades 9 through 11; grade 12 or GED; some college, associate’s degree or technical degree; bachelor’s degree; any post graduate studies), years since HIV diagnosis, monthly income, and unstable housing status in the past 12-months (no; yes) were collected. CD4 + T cell count and HIV-1 RNA viral load were collected from participant’s electronic medical records on or near the survey completion date (all data were at least within 2 months before or after the survey completion date). Additional covariates measured are as follows: HIV disclosure status was assessed using one-item that assessed whether participants disclosed their HIV status to someone or not. Self-rated Health was measured using a single item, “in general, how would you rate your health” on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Poor to 5 = Excellent). Participants were dichotomized into two categories (Poor/fair, Good to Excellent) based on their response. Drug use was measured 10-item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) [20] that assesses drug use in the past 12 months. Scores 0–2 indicate no to low level of problems related to drug abuse.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were employed to calculate the means and standard deviations of the continuous variables and the percentage and frequency of the categorical variables. Due to low response rates for some categorical demographic covariates, we collapsed categories to have adequate cell sizes. These were race (African American; Non-African American), sexual orientation (heterosexual; non-heterosexual), and education (less than high school; high school/GED; greater than high school). Bivariate analyses were performed to examine the association between depressive symptoms and study variables/covariates using an independent t-test, one-way ANOVA, or Pearson’s correlation, as appropriate. Baron and Kenny’s (1986) criteria informed the mediation analysis and we used path analysis to test the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between HIV-related stigma and depressive symptoms. In the path analysis, we controlled for covariates that had signifcant bivariate relationships with endogenous variables (mediator and outcome). Demographic covariates including biological sex and monthly income were controlled for their clinical relevance as well. We assessed the model fit using chi-squared test (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Non-significant χ2, CFI and TLI of greater than 0.95, and the RMSEA less than 0.08 indicate good model fit (43, 44). All analyses were performed using Stata v14.2 with an alpha = 0.05 for statistical significance.

Results

Study characteristics are reported in Table 1. Of the 146 older PWH included in this secondary data analysis, the majority were African American (AA; 85.6%), male (60.3%), heterosexual (63%), and had greater than high school education (41%). Seventeen people reported past unstable housing and non-disclosure of their HIV status. Median monthly income was $754.00 (IQR = 391.50) with more than half (69.2%) reporting income less than $1,000. Only about 10% of participants (n = 14) had an AIDS-defining CD4 + T cell count (< 200 cells/mm3) while more than half (66.2%) had viral suppression (defined by < 40 copies/mL). The mean score on DAST-10 was 1.21, indicating a low level of drug abuse. Bivariate analyses showed that self-rated health (t = 4.665, p = .018) and past unstable housing (t=−3.631; p < .001) were related to depressive symptoms and these were controlled as covariates in the subsequent path analysis.

Table. 1.

Characteristics of the Sample (N = 146)

| Characteristic | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | |||

| Race | |||

| African American/Black | 125 (85.6) | ||

| Non-African American/Black | 21 (14.4) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Born male | 90 (61.6) | ||

| Born female | 55 (37.7) | ||

| Not reported | 1(0.7) | ||

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual or Straight | 92 (63.0) | ||

| Non-heterosexual | 54 (37.0) | ||

| Education | |||

| <High school | 32 (22.0) | ||

| High school graduate / GED | 54 (37.0) | ||

| >High school | 60 (41.0) | ||

| Unstable housing in the past 12 months | 17 (11.6) | ||

| aCD4+ T cell count < 200 cells/mm3 | 14 (9.72) | ||

| bViral suppression (< 40 copies/mL) | 96 (66.23) | ||

| HIV disclosure (to no one) | 17 (11.6) | ||

| Self-rated health (poor/fair) | 34 (23.3) | ||

| Mean (SD) | Min | Max | |

| Age, years | 56.53 (4.55) | 50 | 72 |

| Monthly income, dollars | 957.63 (686.72) | 0 | 6,500 |

| Time since HIV diagnosis, years | 18.10 (8.36) | 2 | 34 |

| Drug use | 1.21(1.92) | 0 | 9 |

| Depressive symptoms | 10.86 (10.31) | 0 | 47 |

| HIV-related stigma | 1.94 (1.94) | 0 | 6 |

| Loneliness | 47.2 (10.1) | 33.9 | 71.8 |

n=144;

n=145

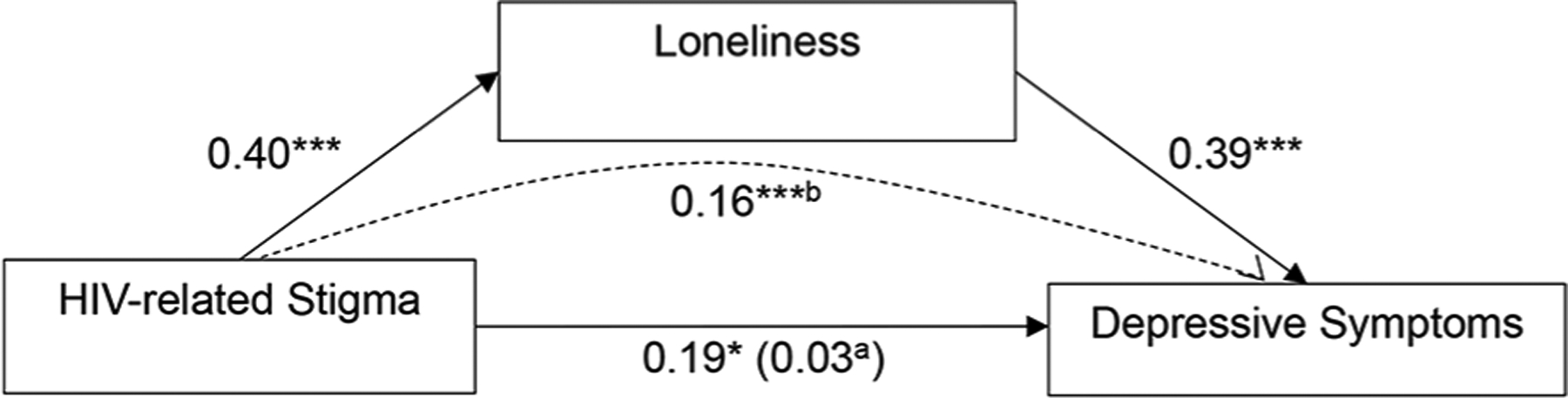

Findings from the path analysis are illustrated in Fig. 1 and include standardized beta coefficients (β). Higher HIV-related stigma was associated with higher loneliness (β = 0.40, p < .001), which was in turn related to higher depressive symptoms (β = 0.39, p < .001). Self-rated health (β=−0.24, p = .0001) and past unstable housing status (β = 0.18, p = .008) remained as significant covariates of depressive symptoms. There was a significant indirect effect of loneliness on the association between HIV-related stigma and depressive symptoms (β = 0.16, p < .001). The final model reflected a good fit (χ2 = 0.09, p = .765; CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.09, RMSEA < 0.001) and accounted for 35% of the variance in symptoms of depression and 28% of the variance in loneliness.

Figure 1.

Mediating Effect of Loneliness on the Relationship Between HIV-related Stigma and Depressive Symptoms

Note. Associations are presented as standardized beta coefficients. Model controls for the effect of self-rated health, past unstable housing, monthly income, and biological sex on the endogenous variables.

a when loneliness is in the model.

b showing mediation through loneliness.

*p < .05; ***p < .001.

Discussion

The objective of the study was to test the mediating role of loneliness in the association between stigma and symptoms of depression. The main finding of the study was that loneliness mediated the relationship between HIV-related stigma and depressive symptoms among older PWH. HIV-related stigma was associated with loneliness, which was associated with depressive symptoms. There was also a direct relationship between HIV-related stigma and depressive symptoms.

Our findings align with prior studies that have shown the effect of loneliness on depression among older PWH. Prior research using cross-sectional designs found that greater loneliness was associated with greater depressive symptoms among older PWH [13, 14]. Extant research in gerontological literature suggests that loneliness is a strong predictor of changes in depressive symptoms over time in middle-aged and older adults [21, 22]. A five-year prospective study using an ethnically diverse sample aged 50–68 in the United States found that loneliness predicted subsequent changes in depressive symptoms in follow-up years, but not vice versa [21]. Similarly, a prospective study using a nationally representative cohort of adults aged 50 years and older in England found that loneliness at baseline was associated with greater depression severity during a 12-year follow up period [22]. These findings, along with our significant results of a mediating role of loneliness on the association between HIV-related stigma and depressive symptoms, suggests the need to address loneliness to prevent and attenuate symptoms of depression and their subsequent negative health sequela. A longitudinal study of loneliness, stigma, and depressive symptoms in the context of HIV and aging is needed to understand the potential long-term effect and explain the causal trajectory of loneliness on symptoms of depression, as well as on health outcomes.

Our finding on the relationship between stigma and depressive symptoms is consistent with previous research [13] that showed that HIV-related stigma was statistically higher among those with greater depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥ 23) compared to older PWH with fewer depressive symptoms (CES-D < 23). Our findings are consistent with prior studies in other fields that assessed the mediating role of loneliness on the association between stigma and depressive symptoms. A cross-sectional study of 110 Polish patients with psychotic disorders found that loneliness was a full mediator of the association between internalized stigma and depressive symptoms [23]. Similarly, a recent study found the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between HIV-related stigma and depressive symptoms in women living with HIV, which in turn, led to suboptimal ART adherence [24].

There are some limitations to consider when interpreting the study’s findings. Its cross-sectional design precludes inferences about causality and limitations exist with interpreting the findings from our cross-sectional mediation. Future studies should consider an extension of mediation analysis using longitudinal data to truly assess the role that loneliness has on the association between stigma and depressive symptoms with an established temporal sequence. Generalizability may be limited since our sample was predominately male, Black, heterosexual, and had been living with HIV for many years. However, some of these characteristics are similar to the current HIV epidemic in the South. Despite the current literature suggesting that there are sex-based differences in the rates of depression– such that higher rates of depression are often seen in women than in men [25, 26]– our findings had no differences by sex. This could be due to the relatively low number of women in our sample. Furthermore, our women sample was nearly all (n = 50) Black. Given that women are underrepresented in research in the general and in particularly in HIV research, more focused efforts in engaging and reaching women aging with HIV in research are needed. Other important covariates and confounders of depression including alcohol use and unemployment [26, 27], were considered in our preliminary analysis but they had no effect in our results. This might be due to our small sample size. Future studies should leverage a larger dataset to build a more robust statistical model to include more covariates/confounders and to conduct complex statistical analyses including serial mediational analysis on the association between stigma and depressive symptoms. Additionally, potentially positive factors of aging, such as resiliency and coping [28], may affect the relationships shown in this analysis, but these variables were not available in the data and results would vary by some of these positive factors. Similarly, other unmeasured variables may have accounted for the associations found in the current study. Future studies would benefit from including measures of positive factors related to aging to assess if they serve as a protectors to the findings shown in this study.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the relationship between HIV-related stigma and depressive symptoms is mediated by loneliness. Addressing depressive symptoms as well as its associated negative health outcomes may require multi-faceted interventions targeting psychosocial and interpersonal factors including HIV-related stigma and loneliness. Future studies should examine the effectiveness of interventions that address HIV-related stigma and loneliness simultaneously.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (F31NR015975). MJB is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH115794). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bing EG, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orlando M, et al. Re-estimating the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a nationally representative sample of persons receiving care for HIV: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2002;11(2):75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook JA, et al. Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Correlates of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders and Associations with HIV Risk Behaviors in a Multisite Cohort of Women Living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(10):3141–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Do AN, et al. Excess burden of depression among HIV-infected persons receiving medical care in the united states: data from the medical monitoring project and the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e92842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubé B, et al. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of HIV infection and AIDS. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005;30(4):237–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Z, Schimmele CM, Chappell NL. Aging and late-life depression. J Aging Health. 2012;24(1):3–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havlik RJ, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Comorbidities and depression in older adults with HIV. Sex Health. 2011;8(4):551–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heckman TG, et al. Psychological symptoms among persons 50 years of age and older living with HIV disease. Aging Ment Health. 2002;6(2):121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rueda S, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipira L, et al. HIV-Related Stigma and Viral Suppression Among African-American Women: Exploring the Mediating Roles of Depression and ART Nonadherence. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(8):2025–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turan B, et al. Longitudinal association between internalized HIV stigma and antiretroviral therapy adherence for women living with HIV: the mediating role of depression. Aids. 2019;33(3):571–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grov C, et al. Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care. 2010;22(5):630–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo-Jeong M, et al. Correlates of loneliness in older persons living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2020;32(7):869–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalichman SC, et al. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: the Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella D, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.PROMIS. PROMIS social isolation: a brief guide to the PROMIS social isolation instruments. 2015; Available from: https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS%20Social%20Isolation%20Scoring%20Manual.pdf.

- 18.Eaton WW, et al. , Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R). 2004.

- 19.Van Dam NT, Earleywine M. Validation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale—Revised (CESD-R): Pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186(1):128–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7(4):363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(2):453–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SL, et al. The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among adults aged 50 years and older: a 12-year population-based cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(1):48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Świtaj P, et al. Loneliness mediates the relationship between internalised stigma and depression among patients with psychotic disorders. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60(8):733–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turan B, et al. Mechanisms for the Negative Effects of Internalized HIV-Related Stigma on Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence in Women: The Mediating Roles of Social Isolation and Depression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(2):198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labaka A, et al. Biological Sex Differences in Depression: A Systematic Review. Biol Res Nurs. 2018;20(4):383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanni MG, et al. Depression in HIV Infected Patients: a Review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;17(1):530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuster R, Bornovalova M, Hunt E. The influence of depression on the progression of HIV: direct and indirect effects. Behav Modif. 2012;36(2):123–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen NB, et al. The structure of coping among older adults living with HIV/AIDS and depressive symptoms. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(2):198–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]