Summary

A biopsy of lymphoid tissue is currently required to diagnose Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)-associated multicentric Castleman disease (KSHV– MCD). Patients showing clinical manifestations of KSHV–MCD but no pathological changes of KSHV–MCD are diagnosed as KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome. However, a lymph node biopsy is not always feasible to make the distinction. A pathognomonic feature of lymph nodes in KSHV–MCD is the expansion of KSHV-infected, lambda-restricted but polyclonal plasmablasts. To investigate whether these cells also reside in extra-nodal sites, effusion from 11 patients with KSHV–MCD and 19 with KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome was analysed by multiparametric flow cytometry. A distinct, lambda-restricted plasmablastic population (LRP) with highly consistent immunophenotype was detected in effusions in 8/11 patients with KSHV–MCD. The same population was also observed in 7/19 patients with KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome. The detection of LRP stratified KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome into two clinically distinct subgroups; those with detectable LRP closely resembled KSHV–MCD, showing similar KSHV viral load, comparable severity of thrombocytopenia and hypoalbuminaemia, and similar incidences of hepatosplenomegaly. Collectively, the detection of LRP by flow cytometry can serve as a valuable tool in diagnosing KSHV–MCD. KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome with LRP in effusions may represent a liquid-form of KSHV–MCD.

Keywords: flow cytometry, KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome, KSHV–MCD, lambda-restricted plasmablasts

INTRODUCTION

Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the aetiologic agent of Kaposi sarcoma, KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman disease (KSHV–MCD), and primary effusion lymphoma (PEL).1 Recently, another KSHV-associated condition, the KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome, has been described.2 Its clinical manifestations and laboratory abnormalities resemble those of KSHV–MCD, but lack the pathological changes diagnostic of KSHV–MCD.

KSHV–MCD occurs predominantly among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection.3–5 The patients typically manifest periodic episodes of systemic inflammation with lymphadenopathy and constitutional symptoms. Laboratory abnormalities include cytopenia, hypoalbuminaemia, hyponatraemia, and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). Due to its variable and non-specific manifestations, KSHV–MCD often poses significant diagnostic challenges. Currently, a lymph node biopsy (or examination of splenic specimen) is required to establish the diagnosis.6,7 The affected nodes typically show increased vascularity and regressed follicles with perifollicular KSHV-infected plasmablasts. These plasmablasts exclusively express IgM and lambda light chain but paradoxically show a polyclonal pattern of immunoglobulin (Ig) gene rearrangement.6–8 They represent a major source of inflammatory cytokines and are considered the principal pathogenic cells of KSHV–MCD.9,10 In contrast, KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring clinical exclusion of other inflammatory conditions and pathologic exclusion of KSHV–MCD and PEL. The precise relationship between KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome and KSHV–MCD is unclear and the cellular source of cytokine production in the absence of nodal plasmablastic proliferation remains a matter of investigation. Currently, there is no standard therapy for KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome.

Pathologic confirmation of KSHV–MCD by lymph node biopsy is limited by multiple factors. First, the histologic features are variable; the presence of concomitant disease such as Kaposi sarcoma in the same lymph node adds an additional layer of complexity. Moreover, a lymph node is not always accessible or a biopsy clinically feasible due to the severe symptoms caused by KSHV–MCD. Importantly, the current pathological criteria for the diagnosis of KSHV–MCD are not applicable in the setting of effusion-based diseases. Persisting or recurring body cavitary effusions are common in patients with HIV and Kaposi sarcoma.11 The aetiology of effusions in these patients can be complex and may represent a manifestation of Kaposi sarcoma itself, KSHV–MCD, PEL, KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome, or infection.12 Accurately distinguishing between these possibilities is difficult but is particularly crucial since they each dictate a substantially different treatment approach. These facts emphasize the need to develop alternative or complementary diagnostic approaches.

Using flow cytometric techniques, we identified a population of KSHV-positive, lambda-restricted plasmablasts in body cavitary effusions of patients diagnosed with KSHV– MCD. The immunophenotype and the monotypic but polyclonal nature of these cells closely resemble those of the KSHV-infected plasmablasts residing in the lymph nodes of KSHV–MCD. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective study including 17 patients with KSHV–MCD and 22 patients with KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome but no concurrent PEL or other types of B-cell lymphoma, aimed at evaluating the diagnostic value of detecting this distinct plasmablastic population using multiparameter flow cytometry in diagnosing KSHV–MCD and in determining the aetiology of KSHV-associated effusions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This retrospective study included 39 patients who had either KSHV–MCD (n = 17) or KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome (n = 22) but no concurrent PEL or other types of B-cell lymphoma (Table 1 and Supplemental Table S1). They all underwent flow cytometry for evaluation of KSHV-associated diseases in effusions, blood, or bone marrow at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) between January 2012 and January 2022. This study included 62 body fluid specimens from 30 patients and 12 peripheral blood/bone marrow specimens from nine patients who did not present with significant effusions.

TABLE 1.

Laboratory findings and features of patients with body cavity effusions in the setting of KSHV-related diseases

| Patient | HIV (copies/ml) | KSHV in effusion (copies/ml) | KSHV in blood (copies/106 cells) | CD4 (cells/μl) | Hgb (g/l) | PLT (K/μl) | Sodium (mmol/l) | Albumin (g/dl) | CRP (mg/l) | IgG (mg/dl) | Kappa LC (mg/dl) | Lambda LC (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCD with LRP in effusions (n = 8) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | <50 | 37 333 | 2364 | 240 | 72 | 67 | 142 | 1.8 | 27.3 | 2520 | 26.2 | 21.1 |

| 2 | 41 871 | 1875 | 33 091 | 5 | 81 | 35 | 134 | 1.5 | 61.9 | 1330 | 7.3 | 8.9 |

| 3 | 79 | 63 014 | 3 272 727 | 113 | 96 | 163 | 130 | 2.3 | NA | 1222 | 16.3 | 17.5 |

| 4 | 70 | 97 000 | 2267 | 476 | 89 | 282 | 139 | 3.7 | 23.7 | 1583 | 9.3 | 12.2 |

| 5 | <20 | 0 | 0 | 257 | 91 | 127 | 139 | 3.3 | 150.5 | 1958 | 5.9 | 4.2 |

| 6 | 132 | 456 000 | 857 143 | 33 | 84 | 44 | 132 | 1.8 | 33.3 | 1031 | 10.7 | 25.6 |

| 7 | NA | NA | 1 446 154 | 238 | 70 | 2 | 137 | 2.3 | 101.5 | 3409 | 19.0 | 22.6 |

| 8 | 458 | 235 294 | 105 263 | 84 | 73 | 52 | 139 | 1.6 | 216.8 | 3605 | 42.4 | 23.4 |

| Median | 132 | 97 000 | 33 091 | 176 | 80 | 67 | 139 | 1.8 | 33.3 | 1770 | 13.5 | 19.3 |

| IQR | 21 104 | 326 043 | 478 888 | 207 | 14 | 134 | 8 | 1.2 | 113.9 | 1938 | 16.6 | 13.5 |

| KICS with LRP in effusions (n = 7) | ||||||||||||

| 9 | <20 | 9 538 462 | 340 000 | 20 | 73 | 29 | 131 | 2.0 | 147 | 924 | 6.0 | 4.0 |

| 10 | <20 | 11 084 337 | 350 000 | 46 | 92 | 81 | 134 | 2.4 | 83.4 | 1071 | 6.4 | 5.4 |

| 11 | <20 | 25 455 | 10 465 | 198 | 91 | 221 | 134 | 1.4 | 65.8 | 2670 | 15.2 | 10.2 |

| 12 | 26 | 2625 | 758 | 511 | 79 | 450 | 131 | 1.3 | 13.2 | 411 | 5.5 | 8.8 |

| 13 | 651 | 161 | 8 341 674 | 16 | 83 | 116 | 132 | 2.3 | 62.1 | 1964 | 15.8 | 10.3 |

| 14 | Not detected | 7667 | 3019 | 31 | 91 | 96 | 128 | 1.6 | 31 | 1070 | 10.6 | 12.3 |

| 15 | <20 | 147 126 | 304 000 | 193 | 144 | 86 | 137 | 2.9 | 50.9 | 962 | 3.7 | 2.8 |

| Median | 20 | 77 396 | 322 000 | 46 | 87 | 91 | 132 | 2.2 | 56.5 | 1070 | 6.4 | 8.8 |

| IQR | 167 | 9 922 921 | 2 345 464 | 178 | 28 | 132 | 5 | 1.0 | 72.8 | 1040 | 9.7 | 6.3 |

| MCD without LRP in effusions (n = 3) | ||||||||||||

| 16 | <20 | 0 | 94 737 | 174 | 94 | 217 | 137 | 2.9 | 91.3 | 650 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| 17 | Not detected | Positive | 2204 | 346 | 111 | 263 | 142 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 745 | 2.9 | 1.9 |

| 18 | 83 | 200 | 200 | 167 | 118 | 140 | 138 | 3.2 | 91.5 | 1153 | 4.0 | 3.3 |

| Median | 52 | 100 | 47 469 | 171 | 106 | 179 | 138 | 3.1 | 91.4 | 902 | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| IQR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| KICS without LRP in effusions (n = 12) | ||||||||||||

| 19 | Not detected | 538 | Positive | 115 | 100 | 301 | 134 | 2.3 | 29.9 | NA | NA | NA |

| 20 | 123 | 13 636 | 0 | 118 | 76 | 154 | 130 | 2.8 | 129.1 | 3872 | 119.4 | 63.5 |

| 21 | <20 | Positive | 0 | 302 | 101 | 914 | 137 | 3.3 | 125.4 | 1325 | 5.8 | 3.04 |

| 22 | 1271 | 5895 | 1538 | 82 | 77 | 221 | 131 | 2.8 | 71.1 | 2807 | 21.2 | 18.4 |

| 23 | 150 038 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 88 | 304 | 134 | 3.1 | 12.9 | 1950 | 4.9 | 3.5 |

| 24 | 35 | 13 913 | 343 | 1 | 74 | 138 | 138 | 2.5 | 42.1 | 2138 | 11.3 | 9.3 |

| 25 | 122 | 349 | 12 000 | 25 | 73 | 370 | 140 | 3.8 | 9.6 | 1092 | 6.8 | 4.3 |

| 26 | Not detected | 53 | 48 571 | 95 | 87 | 222 | 127 | 2.8 | 4.6 | 860 | NA | NA |

| 27 | Not detected | 22 | Positive | 29 | 87 | 311 | 138 | 3.2 | 79.8 | 877 | 6.3 | 3.5 |

| 28 | 45 | 1053 | 360 | 80 | 81 | 216 | 132 | 3.0 | 108.7 | 1816 | 13.8 | 7.9 |

| 29 | Not detected | 0 | 0 | NA | 100 | 315 | 138 | 2.3 | 79.7 | NA | NA | NA |

| 30 | Not detected | 0 | 0 | 151 | 101 | 218 | 137 | 3.8 | 15.8 | 1555 | 2.2 | 3.2 |

| Median | 123 | 3474 | 352 | 80 | 77 | 219 | 133 | 2.9 | 56.6 | 2044 | 12.6 | 8.6 |

| IQR | 38 420 | 13 444 | 4154 | 72 | 9 | 171 | 8 | 0.6 | 101.7 | 1438 | 39.4 | 25.6 |

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; Hgb, haemoglobin; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; Ig, immunoglobulin; IQR, interquartile range; KICS, KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome; KSHV, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus; LC, light chain; LRP, lambda-restricted plasmablasts; MCD, multicentric Castleman disease; NA, not available/applicable; PLT, platelet.

The diagnosis of KSHV–MCD was made based on the combination of clinical manifestations and pathological confirmation of nodal involvement.8 Patients were classified as having KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome if they met the previously proposed working criteria (Supplemental Table S2)13,14 with either a negative biopsy or no definite lymphadenopathy and no PEL. Clinical information was collected from the electronic medical records. Pertinent laboratory findings at the time (+/− seven days) of flow cytometric analysis were obtained, including HIV viral load, KSHV viral load in peripheral blood and effusion, haemoglobin, platelet count, absolute CD4-positive T cells in peripheral blood, CRP, serum immunoglobulin (IgG) and light chains. Additionally, seven patients at initial diagnosis of PEL were also studied to assess whether flow cytometry can reliably distinguish between LRP and PEL. All patients were enrolled on protocols for the study of the natural history of KSHV-related diseases and/or sample collection (NCT01419561, NCT00092222, NCT00006518). These protocols were approved by the NCI Institutional Review Board (and now the NIH Institutional Review Board), registered at ClinicalTrials.gov and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. Deidentified participant data are available upon reasonable request made to the corresponding author H-W.W.

Flow cytometry

The specimens were collected and immediately sent to the NCI Flow Cytometry Laboratory for eight-colour flow cytometry at ambient temperature. The preparation of samples included NH4Cl whole-blood lysis and phosphate-buffered saline wash. Subsequently, the samples were incubated with cocktails of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for 30 minutes at room temperature. Intracellular antigen staining (IRF4 and LANA-1) was performed following completion of surface antigen staining, fixation and permeabilization. Cells were then washed, pelleted and fixed in 1% formalin. The specimens were acquired on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) and analysed with FCSExpress software (DeNovo Software). A total of 1 000 000 events were collected per tube when possible.

Viral load studies

KSHV viral load assays were performed using the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells and effusion-associated KSHV viral DNA were quantified using primers from KSHV K6 regions as previously described.2 Cell number quantifications were performed using a human endogenous retrovirus 3 (ERV-3) assay.15 Viral loads were expressed as copies per million cell equivalents and effusion viral loads were expressed as copies/106 mononuclear cells.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, was performed for comparisons between groups. Analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 17, SPSS Inc.). p-values are 2-tailed; a value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Detection of distinct lambda-restricted plasmablasts in effusions from patients with KSHV–MCD by flow cytometry

This study included 17 patients with pathologically confirmed KSHV–MCD and 22 patients with KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome; none of them had concurrent PEL or other B-cell lymphomas. Among these 39 patients, 30 (11 with KSHV–MCD and 19 with KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome) had developed body cavity effusions that were evaluated by flow cytometry (Table 1).

All 11 patients with KSHV–MCD and effusions were cisgender male, with a median age at presentation of 40 years (range 25–67). All except one (patient no. 17) were HIV co-infected and were receiving antiretroviral therapy; eight (72.7%) had suppressed HIV viral load (<200 copies/ml). All but one (patient no.1) had biopsy-proven Kaposi sarcoma. The median time between HIV, Kaposi sarcoma, and KSHV–MCD diagnosis and first presentation of effusions was 8.5 months (range 0.6–122.2), 0.6 months (range 0–120.2) and 0.3 months (range 0–101.2) respectively.

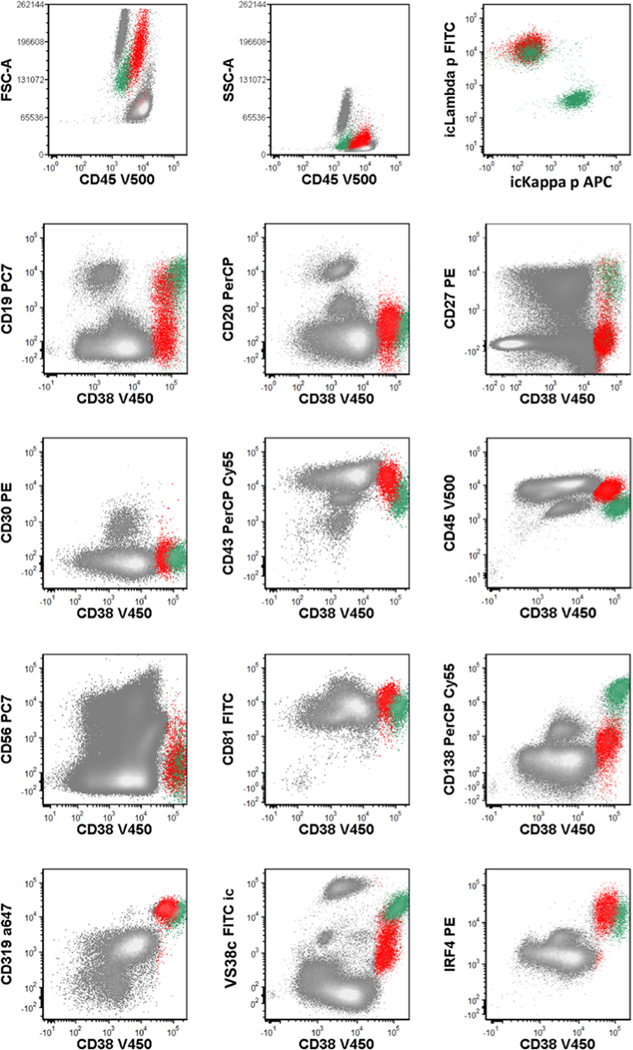

In eight of the 11 patients (72.7%) with KSHV–MCD, a distinct lambda-restricted plasmablasts population was identified in effusions at least once over the course of the study (Supplemental Table S1). Herein we use LRP to denote specifically this lambda-restricted plasmablast population detected by flow cytometry. The LRP showed high forward and side-scatter light dispersion properties and a distinctive immunophenotypic profile that was highly consistent across all specimens (Figures 1 and 2). It expressed bright CD38, variable CD19, IRF4, Vs38c and CD319 but was dim to negative for CD138 and CD20. This immunophenotype matches the immunophenotypic profile of KSHV-infected plasmablasts seen in lymph nodes of MCD.16 In the effusions, there was usually a prominent polytypic plasma cell population in the background; LRP can be distinguished by their different antigen expression pattern including higher forward scatter, brighter CD45, dimmer CD38 and VS38c, and dim or absent CD19 and CD138. Importantly, LRP exhibited surface and intracytoplasmic lambda restriction. The number of LRP was variable but typically low, with a median of 0.06% of total mononuclear cells (range, 0.03%–3.1%).

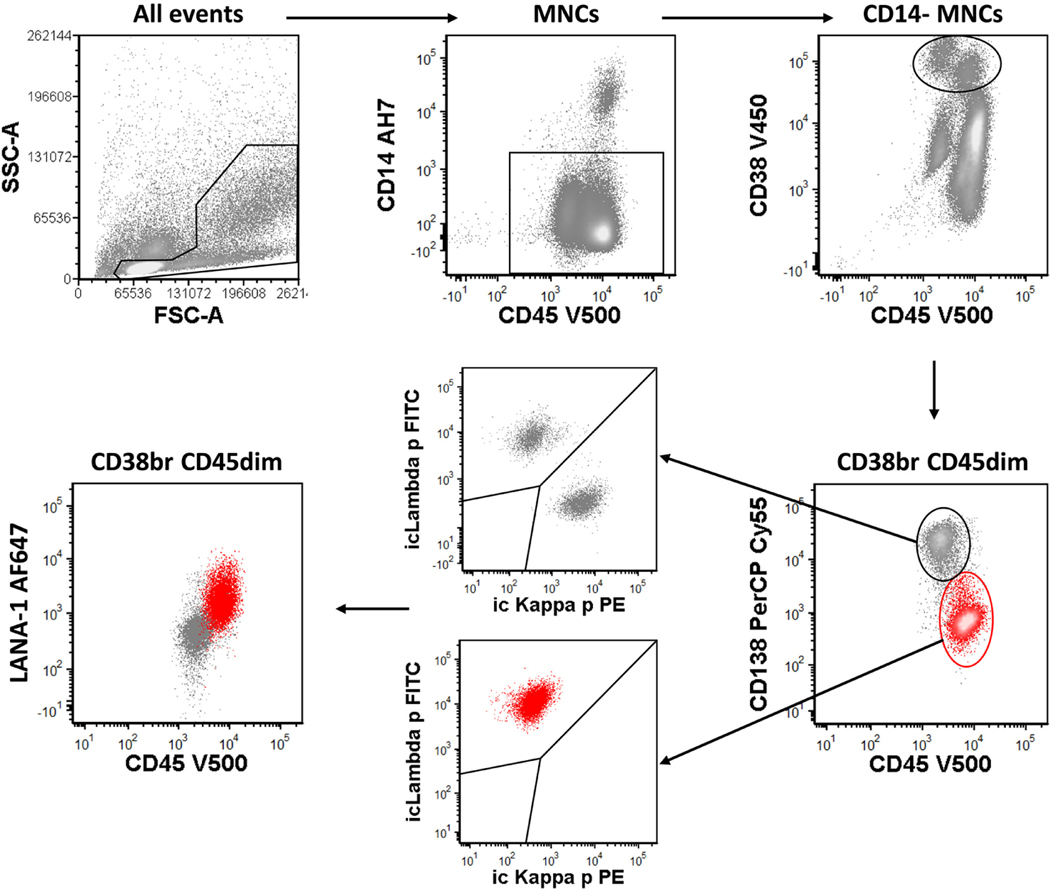

FIGURE 1.

Sequential gating to identify LRP (red). Abbreviations: br, bright; LRP, lambda-restricted plasmablasts; MNC, mononuclear cells

FIGURE 2.

Representative immunophenotype of LRP. Abbreviation: LRP, lambda-restricted plasmablasts. Red, LRP; green, normal plasma cells

To further investigate if LRP represent KSHV-infected plasmablasts, similar to those residing in KSHV–MCD lymph nodes, the expression of latency-associated nuclear antigen-1 (LANA-1) — a KSHV encoded protein that is highly expressed in infected cells — was assessed by flow cytometry in effusions from two patients. The LRP population in both patients demonstrated LANA-1 positivity by flow cytometry (Figure 1). The positivity of LANA-1 was also confirmed by immunoperoxidase staining on cytology preparations of effusions in seven out of eight patients (Figure 3A and Supplemental Table S1). Additionally, six of the eight patients with monotypic LRP demonstrated polyclonal Ig rearrangements in the corresponding specimens by PCR (Supplemental Table S1). These results provided convincing evidence that the LRP in effusions represent the extra-nodal counterpart of the KSHV-infected plasmablasts in lymph nodes. This notion was further strongly supported by the detection of cells sharing the identical immunophenotype using flow cytometry in a lymph node pathologically confirmed with KSHV–MCD (patient no. S2, Supplemental Table S3, Supplemental Figure S1).

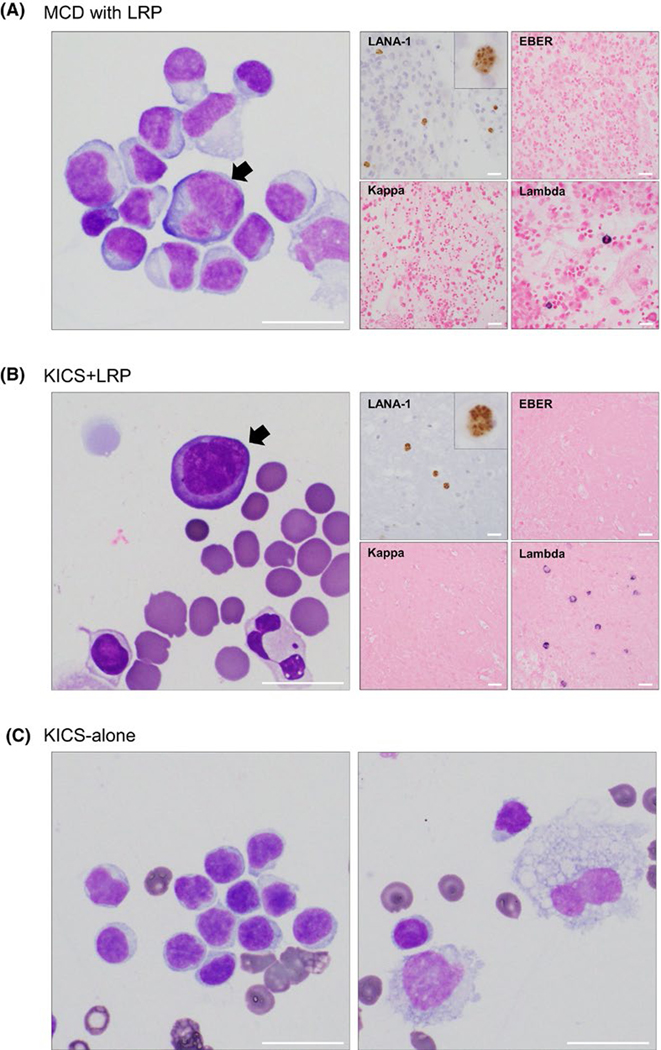

FIGURE 3.

Representative cytologic features of KSHV-associated effusion specimens. (A) Atypical lymphoid cells (arrow) with enlarged and irregular nuclei and basophilic cytoplasm were detected in the effusion sample from a patient with KSHV–MCD. Ancillary studies demonstrated positivity of latency-associated nuclear antigen-1 (LANA-1) and lambda light chain restriction in the atypical cells, while in-situ hybridization for EBV (EBER) was negative. (B) Representative effusion specimen from a patient with KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome with LRP detected by flow cytometry (KICS + LRP) demonstrated atypical lymphoid cells (arrow) with similar atypical cytomorphology and immunophenotype as those detected in KSHV–MCD samples (A). (C) Representative effusion specimen from a patient with KICS alone demonstrated reactive lymphocytes (left) and histiocytes (right), Abbreviations: EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; KICS, KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome; KSHV, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus; LRP, lambda-restricted plasmablasts; MCD, multicentric Castleman disease

The use of flow cytometric analysis to distinguish lambda-restricted plasmablasts from primary effusion lymphoma

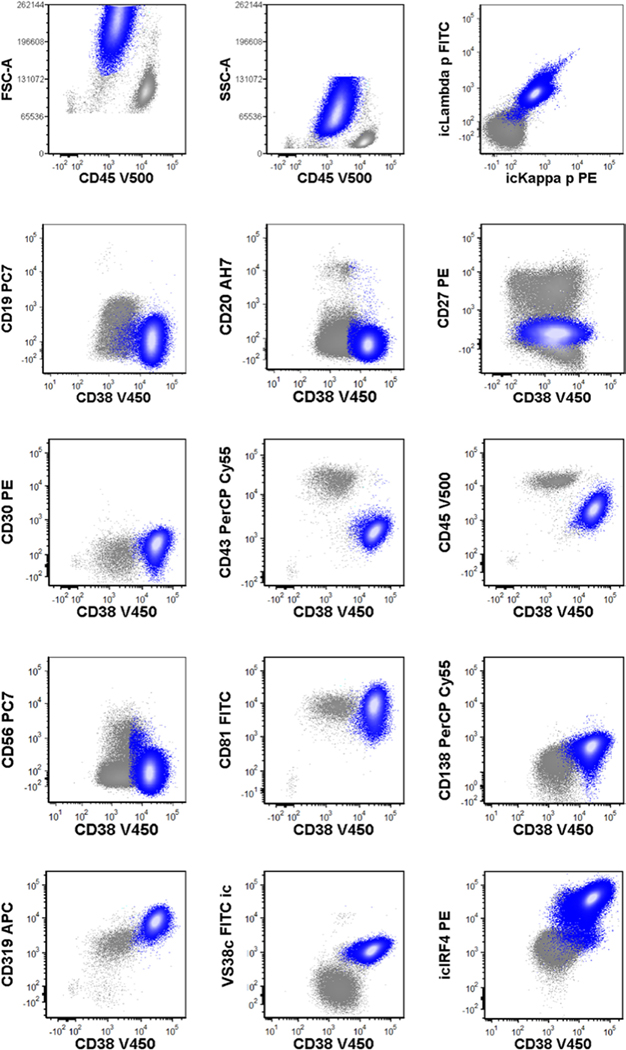

Primary effusion lymphoma is often the major differential diagnosis when these patients develop effusions. Given that the distinction between these two conditions is often challenging, we assessed whether flow cytometry can reliably distinguish one from the other. To this end, we retrospectively reviewed seven cases of PEL at initial diagnosis. Our analysis revealed that PEL cases displayed considerable individual variability in antigen expression patterns (Supplemental Table S4); importantly, none exhibited an immunophenotypic profile identical to the characteristic phenotype of LRP. Additionally, LRP consistently expressed a restricted lambda light chain, while all but one PEL sample showed absence of cytoplasmic and surface light chain expression (Figure 4, Table 3).

FIGURE 4.

Representative immunophenotype of primary effusion lymphoma. Blue, primary effusion lymphoma

TABLE 3.

Immunophenotypic difference between LRP and PEL

| LRP (n = 19) | PEL (n = 7) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lambda restriction | 19/19 | 1/7 | <0.001 |

| Absent light chain expression | 0/19 | 6/7 | <0.001 |

| Bright CD45 expression | 19/19 | 1/7 | <0.001 |

| CD81 positivity | 17/17 | 4/6 | NS |

| Background plasmacytosis | 19/19 | 1/7 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: LRP, lambda-restricted plasmablasts; PEL, primary effusion lymphoma.

A few phenotypic features further distinguished LRP from PEL. Bright CD45 expression comparable to that of mature lymphocytes was a characteristic of LRP, but it was uncommon in PEL. All but one PEL case demonstrated dim to moderate CD45 expression. Furthermore, LRP in effusions were characteristically associated with prominent polytypic plasmacytosis, which was noted in only one PEL specimen. While LRP could be distinguished from normal plasma cells by the differential expression levels of plasma cell markers including CD19, CD138, CD319 and Vs38c, the overall phenotypic profile of LRP still formed a continuum with the plasma cells. In comparison, the immunophenotypic profile of PEL was readily separated from that of normal plasma cells (Figure 4, Table 3). Another helpful feature was the size of the cell populations. PEL clones typically dominated the cellular compartments at initial presentation, comprising a median of 75% of total mononuclear cells (range 24%–97%). In contrast, the numbers of LRP were consistently low in KSHV–MCD or KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome. However, this feature may become less reliable in the post-therapy setting.

The presence of lambda-restricted plasmablasts identified a subset of KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome closely related to KSHV–MCD

Among the 19 patients diagnosed with KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome, LRP were observed in the effusions in nine patients, when present comprising a median of 0.87% (range, 0.01%–8.7%) of the mononuclear cells. Notably, there is a weak correlation between the frequencies of LRP and KSHV viral load in effusion when patients with KSHV–MCD and those with KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome were combined for a bivariate correlation analysis (correlation coefficient = 0.67, p = 0.009). Cytologic examination of effusions containing LRP demonstrated scattered large atypical plasmacytoid cells that were morphologically and immunophenotypically similar to those observed in effusions of patients with KSHV–MCD (Figure 3A & 3B). Effusions where LRP were not detected by flow cytometry showed mainly reactive changes only (Figure 3C).

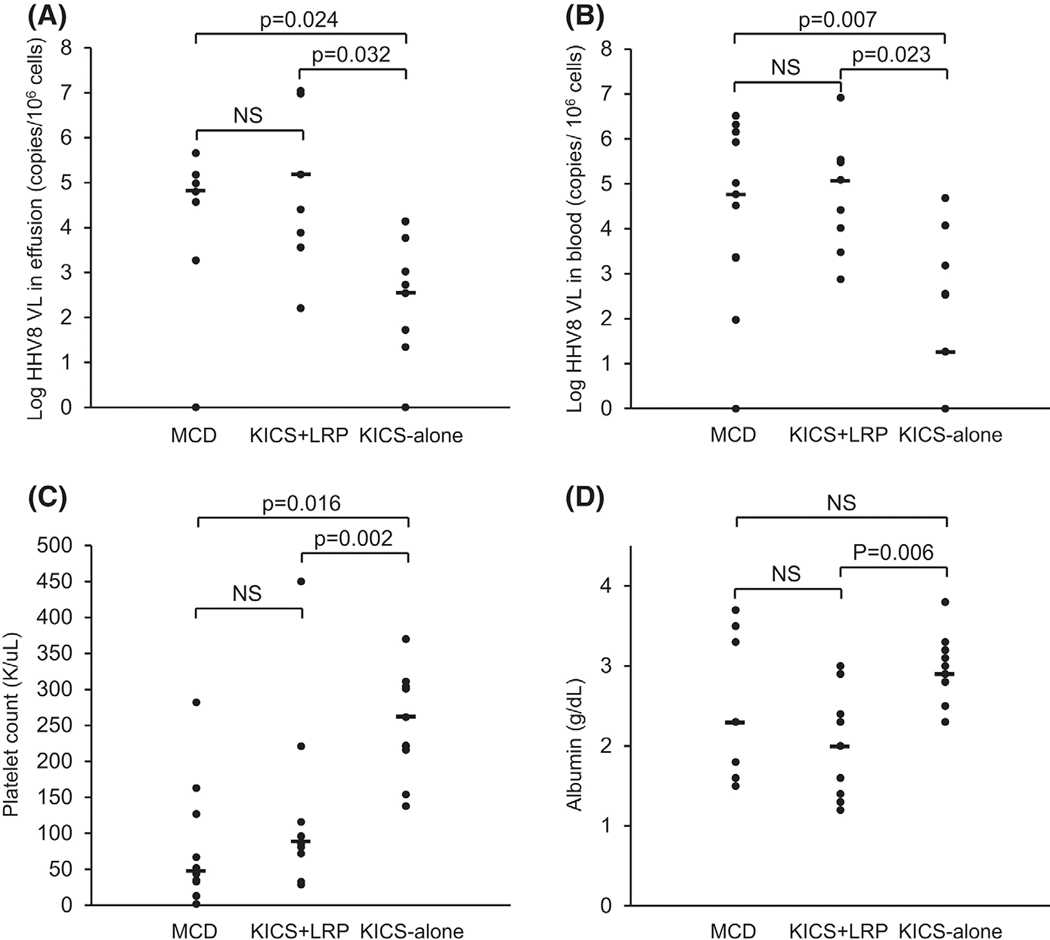

We then queried whether the detection of LRP could serve as a useful marker to illuminate the heterogeneity of KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome. We divided KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome into two subgroups based on the presence of LRP: KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome + LRP (KICS + LRP) versus KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome alone (KICS alone). A comparison between the two subgroups revealed several important differences in clinical manifestations and laboratory findings (Figure 5 and Table 2). Patients with KICS + LRP demonstrated more severe hypoalbuminaemia (p = 0.006), a key feature of KSHV–MCD. The presence of LRP was also associated with more evident thrombocytopenia. Five out of seven patients with KICS + LRP had thrombocytopenia (<150 K/μl), which was severe in one (<50 K/μl). In sharp contrast, thrombocytopenia, although considered to be a key diagnostic feature of KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome, was observed in only one of 12 patients in the KICS-alone group (p = 0.02). Furthermore, patients with KICS + LRP had more frequent hepatosplenomegaly (p = 0.04).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of laboratory parameters among patients with different HHV8-related diseases. HHV8, human herpesvirus 8; KICS, KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome; KSHV, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus; LRP, lambda-restricted plasmablasts detected by flow cytometry; NS, not significant; VL, viral load.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of clinicopathological features among patients with HHV8-related diseases

| MCD | KICS | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With LRP | No LRP | KICS + LRP vs KICS alone | MCD vs KICS + LRP | MCD vs KICS alone | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Number | 11 | 7 | 12 | — | — | — |

| Age, yrs | 40 (25–67) | 42 (24–68) | 30 (27–53) | NS | NS | NS |

| Male/female | 11/0 | 6/1 | 11/1 | NS | NS | NS |

| HIV/HHV8 parameters | ||||||

| HHV8 in effusion, copies/106 cells | 37 333 (0–456 000) | 25 455 (161–11 084 337) | 701 (0–13 913) | 0.032 | NS | 0.024 |

| HHV8 in blood, copies/106 cells | 33 091 (0–3 272 727) | 304 000 (758–8 341 674) | 352 (0–48 571) | 0.023 | NS | 0.007 |

| HIV, copies/ml | 70 (0–41 871) | 20 (0–651) | 45 (0–150 038) | NS | NS | NS |

| CD4, cells/μl | 174 (5–476) | 46 (16–511) | 80 (1–302) | NS | NS | NS |

| Blood cell counts | ||||||

| Hgb, g/l | 89 (72–118) | 91 (73–144) | 81 (73–101) | NS | NS | NS |

| PLT, K/μl | 127 (44–282) | 96 (29–450) | 221 (138–914) | 0.02 | NS | 0.016 |

| Inflammatory parameters | ||||||

| Albumin, g/dl | 2.9 (1.5–3.7) | 2.0 (1.3–2.9) | 3.0 (2.3–3.8) | 0.006 | NS | NS |

| CRP, mg/l | 61.9 (2.8–216.8) | 62.1 (13.2–147.0) | 42.1 (4.6–129.1) | NS | NS | NS |

| IgG, mg/dl | 1330 (650–3605) | 1070 (411–2670) | 1685 (860–3872) | NS | NS | NS |

| Kappa LC, mg/dl | 7.3 (1.3–42.4) | 6.4 (3.7–15.8) | 6.8 (2.2–119.4) | NS | NS | NS |

| Lambda LC, mg/dl | 8.9 (1.5–25.6) | 8.8 (2.8–12.3) | 4.3 (3.0–63.5) | NS | NS | NS |

| Sodium, mmol/l | 139 (132–142) | 132 (128–137) | 134 (127–140) | NS | 0.012 | NS |

| Pathologic features | ||||||

| LRP, % of MNCa | 0.06 (0.03–3.10) | 0.87 (0.01–8.70) | — | NS | NS | — |

| Abnormal cytology | 9/11 (81.8%) | 5/7 (71.4%) | 4/12 (33.3%) | NS | NS | 0.036 |

| Clonal Ig | 3/11 (27.0%) | 1/7 (14.3%) | 3/12 (25.0%) | NS | NS | NS |

| Hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly | 6/11 (54.5%) | 5/7 (71.4%) | 2/12 (16.7%) | 0.04 | NS | NS |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Death | 6/11 | 4/7 | 6/12 (50%) | NS | NS | NS |

| Complete remissionb | 6/11 (50.0%) | 3/7 (42.9%) | 2/7 (28.6%) | NS | NS | NS |

| Median survival, mos | 86.6 | 12.1 | 23.3 | NS | NS | NS |

Note: For age and laboratory values, figures given are median and range, for other characteristics number and percentage.

Abbreviations: HHV8, human herpesvirus 8; HIV, human immunoideficiency virus; KICS, KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome; KSHV, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus; LRP, lambda-restricted plasmablasts; mos, months; PEL, primary effusion lymphoma.

Frequency of lambda-restricted plasmablasts in the body cavitary fluids, excluding peripheral blood, bone marrow, or peripheral blood.

Treatment response in patients who received rituximab-based regimens.

We then set out to assess whether KICS + LRP is more closely related to KSHV–MCD than KICS alone is. Although by definition, KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome resembles KSHV–MCD in clinical manifestations and laboratory abnormalities, patients in the KICS-alone group displayed several key parameters distinguishable from those with KSHV–MCD, including a significantly lower KSHV viral load in both effusion and blood (p = 0.02 and 0.007 respectively), higher platelet count (p = 0.016), and seemingly less frequent hepatosplenomegaly (p = 0.08). In contrast, KICS + LRP was similar to KSHV–MCD with respect to most clinical and laboratory features (Figure 5 and Table 2), including age at presentation, levels of haemoglobin, platelets (p = 0.8), albumin (p = 0.2), CRP (p = 0.6) and KSHV viral load in effusion (p = 0.4) and peripheral blood (p = 0.5), frequencies of hepatosplenomegaly and percentages of LRP at presentation. Moreover, patients in both groups showed similar complete remission rates following rituximab-based regimens.

Detection of lambda-restricted plasmablasts in peripheral blood and bone marrow from patients with KSHV–MCD and KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome without effusions

To assess whether LRP were also present in other extra-nodal sites, peripheral blood and bone marrow samples were analysed by flow cytometry in patients with KSHV–MCD or KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome who did not have effusions. LRP were detected in three of six (50%) patients with KSHV–MCD, and two of three patients with KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome (Supplemental Table S3). All five patients with detectable LRP showed thrombocytopenia, and four of them were severe (<50 K/μl). By contrast, thrombocytopenia was seen in two of four patients without detectable LRP in the blood or marrow.

DISCUSSION

By using multiparametric flow cytometry, we demonstrated a body cavitary cellular counterpart of KSHV-infected plasmablasts in the lymph nodes that are considered pathognomonic of KSHV–MCD. Detecting these cells (the LRP) using flow cytometry in extra-nodal sites could serve as a powerful tool in diagnosing KSHV–MCD. Notably, KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome could be stratified into two clinically distinct subgroups based on the detection of extra-nodal LRP; those with detectable LRP closely resembled KSHV–MCD. Therefore, we revisit the defining criteria for KSHV–MCD and propose a novel concept of liquid-variant KSHV–MCD.

In this study, LRP were detected in effusions by flow cytometry in eight of 11 (72.7%) patients with pathologically confirmed MCD, and in blood or marrow in three of six (50.0%) patients without effusions. These cells closely resembled the KSHV-infected LRP that proliferate in lymph nodes affected by KSHV–MCD. They expressed plasmacytic markers, including bright CD38 and IRF4; the relatively bright CD45 and dim to negative CD138 indicated that they were at an early stage of plasmacytic differentiation; they exhibited surface and intracellular lambda light chain restriction. The immunophenotype was distinctive, readily distinguishable from normal mature plasma cells, and highly consistent across all patients. Therefore, the gating strategy is straight-forward and consistent; this important advantage ensures the generalizability of this approach to any clinical flow cytometry laboratory.

The detection of LRP by flow cytometry in effusions, blood, or bone marrow can serve as a valuable diagnostic tool in several clinical scenarios. First, it provides a practical and objective tool that supplements lymph node biopsy for evaluation of KSHV-associated diseases especially in patients with HIV. In patients categorized as KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome due to lack of lymphadenopathy or absence of pathological confirmation, detection of LRP may identify a subgroup that is closer to KSHV–MCD. In patients having a history of pathologically confirmed KSHV–MCD, this approach is useful in distinguishing MCD effusions from other inflammatory states or other KSHV-associated diseases, especially PEL. The diagnosis of PEL is based primarily on cytologic evaluation, which can be challenging in some cases. The high prevalence of LANA-1-positive LRP in KSHV–MCD cases and prominent cytologic atypia in a subset of these cells highlights that the diagnosis of PEL cannot rely solely on detection of KSHV-positive cells in effusions, e.g. by LANA-1 immunostains. Although clonality analysis can certainly aid in distinguishing between KSHV–MCD and PEL, it is not uncommon to encounter cases that do not follow their typical patterns of Ig gene rearrangements, as has been reported previously and also observed in the present study (Table 2, Supplemental Table S1).17,18 This study, for the first time, demonstrates that flow cytometry can serve as a valuable adjunctive tool to cytologic examination and clonality analysis in this dilemma. Flow cytometric analysis reliably distinguishes LRP from PEL based on the following features: (1) LRP consistently express restricted lambda light chain, in contrast to the usual absence of light chain expression in PEL. (2) Bright CD45 expression on LRP is a helpful contrast to the dim to moderate CD45 expression in PEL. (3) LRP shows a distinct phenotype of early plasmacytic differentiation and appear to form a continuum with the normal plasma cells usually abundant in the background. Conversely, plasmacytosis is not typically found in PEL and PEL typically exhibits a phenotype readily separate from normal plasma cells. (4) LRP are observed at low frequencies, whereas PEL clones usually dominate the cellular compartments at initial presentation.

Another particularly novel finding of our study is that KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome is heterogeneous and can be stratified into two subgroups based on the presence of LRP; this stratification is justified by their different clinical and laboratory findings. Patients in the KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome-alone (KICS-alone) group displayed several key parameters distinguishable from those with KSHV–MCD, while the subgroup with detectable LRP (KICS + LRP) is similar to active KSHV–MCD in multiple clinical and laboratory aspects. These findings lead to a pertinent question: is KICS + LRP, in fact, a form of KSHV–MCD despite the absence of nodal involvement? The most widely held belief regarding the pathogenesis of KSHV–MCD is that the systemic manifestations and certain features of the nodal pathology are responses to elevated levels of IL-6 and other circulating factors during the cytokine storm.19 A major cellular source or driver of these inflammatory cytokines is believed to be KSHV-infected plasmablasts, which have been considered the principal pathogenic cells. Importantly, our past studies have shown that KSHV–MCD and KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome show comparable levels of key cytokines, including IL-6, vIL-6 and IL-10, both in the effusions and the serum,12,14 Based on these notions, the previous question can be posed in a different way: is the compartment where the KSHV-infected plasmablasts proliferate truly a defining attribute of KSHV–MCD, if cells residing in extra-nodal tissues nonetheless result in KSHV lytic replication, pro-inflammatory cytokine deregulation, and eventually the same clinical end-point?

Perhaps, what is most important is a microenvironment to potentiate growth of plasmablasts by autocrine and paracrine effects and cross-infection. Lymph nodes are not necessarily the only compartments that can exert this function. In support of this, marked expansion of the KSHV-infected plasmablasts in bone marrow and spleen, as well as their release to blood, has been observed in patients with MCD.20–22 The assumption is strongly reinforced in this study, which demonstrates that body cavities could also serve as a reservoir for KSHV replication and a niche for plasmablastic proliferation. Based on the above findings, we propose that KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome with an extra-nodal proliferation of KSHV-infected plasmablasts represent a unique liquid-form variant or, alternatively, an early stage (liquid-phase) of KSHV–MCD.23 Conceptually, there may be a clinical and biological continuum between reactivation of KSHV infection, liquid-form or liquid-phase, and KSHV–MCD with nodal involvement.

In summary, our study highlights the diagnostic utility of LRP detection by flow cytometry in the setting of KSHV-associated diseases. Our observations also reveal that KSHV-associated lymphoid proliferation at extra-nodal sites occurs more commonly than previously appreciated and may contribute to the pro-inflammatory cytokine storm. Finally, we propose that there is a non-nodal form of KSHV– MCD which forms a continuum with nodal KSHV–MCD. A subset of the previously defined KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome with detectable LRP falls into this MCD continuum and may benefit from therapeutic regimens for KSHV–MCD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the entire NCI Flow Cytometry Laboratory for their gracious support and the insightful discussions during the manuscript preparation. The authors also thank Drs. Marriam Aalai, Tanupriya Agrawal and Helmae Wubneh for their assistance in working up the cytology cases.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and by US Federal Funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. 75N91019D00024/HHSN261201500003I.

Footnotes

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Deidentified participant data are available upon reasonable request made to the corresponding author Hao-Wei Wang.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Robert Yarchoan reports receiving research support from Celgene (now Bristol Myers Squibb) through CRADAs with the NCI. Dr. Yarchoan also reports receiving drugs for clinical trials from Merck, EMD-Serano, Eli Lilly, and CTI BioPharma through CRADAs with the NCI, and he has received drug supply for laboratory research from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Robert Yarchoan is a co-inventor on US Patent 10,001,483 entitled “Methods for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma or KSHV-induced lymphoma using immunomodulatory compounds and uses of biomarkers.” An immediate family member of Robert Yarchoan is a co-inventor on patents or patent applications related to internalization of target receptors, epigenetic analysis, and ephrin tyrosine kinase inhibitors. All rights, title, and interest to these patents have been assigned to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; the government conveys a portion of the royalties it receives to its employee inventors under the Federal Technology Transfer Act of 1986 (P.L. 99–502).

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

All patients provided written informed consent.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

Not applicable.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, et al. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uldrick TS, Wang V, O’Mahony D, Aleman K, Wyvill KM, Marshall V, et al. An interleukin-6-related systemic inflammatory syndrome in patients co-infected with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and HIV but without multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:350–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals-Hatem D, Babinet P, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1995;86:1276–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lurain K, Yarchoan R, Uldrick TS. Treatment of Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018;32:75–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramaswami R, Lurain K, Polizzotto MN, Ekwede I, Waldon K, Steinberg SM, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman disease with or without other KSHV diseases. Blood Adv. 2021;5:1660–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang HW, Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. Multicentric Castleman disease: where are we now? Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:294–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou T, Wang HW, Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. Multicentric Castleman disease and the evolution of the concept. Pathologica. 2021;113:339–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swerdlow SHCE Harris NL, Jaffe ES Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J WHO classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du MQ, Liu H, Diss TC, Ye H, Hamoudi RA, Dupin N, et al. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infects monotypic (IgM lambda) but polyclonal naive B cells in Castleman disease and associated lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2001;97:2130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staskus KA, Sun R, Miller G, Racz P, Jaslowski A, Metroka C, et al. Cellular tropism and viral interleukin-6 expression distinguish human herpesvirus 8 involvement in Kaposi’s sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman’s disease. J Virol. 1999;73:4181–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afessa B Pleural effusions and pneumothoraces in AIDS. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2001;7:202–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramaswami R, Lurain K, Marshall VA, Rupert A, Labo N, Cornejo-Castro E, et al. Elevated IL-13 in effusions of patients with HIV and primary effusion lymphoma as compared with other Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated disorders. AIDS. 2021;35:53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polizzotto MN, Uldrick TS, Wyvill KM, Aleman K, Marshall V, Wang V, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with symptomatic Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV)-associated inflammation: prospective characterization of KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:730–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polizzotto MN, Uldrick TS, Hu D, Yarchoan R. Clinical manifestations of Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus lytic activation: multicentric Castleman disease (KSHV-MCD) and the KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan CC, Miley W, Waters D. A quantification of human cells using an ERV-3 real time PCR assay. J Virol Methods. 2001;91:109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chadburn A, Hyjek EM, Tam W, Liu Y, Rengifo T, Cesarman E, et al. Immunophenotypic analysis of the Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV; HHV-8)-infected B cells in HIV+ multicentric Castleman disease (MCD). Histopathology. 2008;53:513–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ascoli V, Lo Coco F, Torelli G, Vallisa D, Cavanna L, Bergonzi C, et al. Human herpesvirus 8-associated primary effusion lymphoma in HIV--patients: a clinicopidemiologic variant resembling classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. Haematologica. 2002;87:339–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catherwood MA, Gonzalez D, Patton C, Dobbin E, Venkatraman L, Alexander HD. Improved clonality assessment in germinal Centre/post-germinal Centre non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas with high rates of somatic hypermutation. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:524–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fajgenbaum DC. Novel insights and therapeutic approaches in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2018;132:2323–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupin N, Diss TL, Kellam P, Tulliez M, Du MQ, Sicard D, et al. HHV-8 is associated with a plasmablastic variant of Castleman disease that is linked to HHV-8-positive plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2000;95:1406–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-Farre B, Martinez D, Lopez-Guerra M, Xipell M, Monclus E, Rovira J, et al. HHV8-related lymphoid proliferations: a broad spectrum of lesions from reactive lymphoid hyperplasia to overt lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:745–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oksenhendler E, Boutboul D, Beldjord K, Meignin V, de Labarthe A, Fieschi C, et al. Human herpesvirus 8+ polyclonal IgMlambda B-cell lymphocytosis mimicking plasmablastic leukemia/lymphoma in HIV-infected patients. Eur J Haematol. 2013;91:497–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyplosz B, Carlotti A, Escaut L, Vignier N, Guettier C, Agbalika F, et al. Initial human herpesvirus-8 rash and multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:684–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.