Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the diagnosis of breast cancer in inner-city African-American and Hispanic women under age 50 to support the importance of screening in this population.

Methods:

This retrospective chart review included women newly diagnosed with breast cancer from 1/1/2015 to 1/1/2019 in a city hospital mainly serving minority patients. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for analysis.

Results:

In this cohort of 108 newly diagnosed African-American (63%) and Hispanic (31%) women, 60/108 (56%) presented with a site of palpable concern for diagnostic workup, and the remaining were diagnosed via asymptomatic screening. Women ages 30-49 were significantly more likely to present with a site of palpable concern when compared to women ages 50-69 (68% vs. 44%, p=0.045). Additionally, women ages 30-49 were more likely to have triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) than women ages 50-69 (20% vs. 10%, p=0.222). However, women ages 30-49 were less likely to have prior mammogram than women ages 50-69 (24% vs. 46%, p=0.062).

Conclusion:

African-American and Hispanic women ages 30-49 were more likely to present with a site of palpable concern and TNBC than those ages 50-69. However, these young minority women ages 30-49 were less likely to have prior screening mammograms when compared to those ages 50-69. Our data highlights the importance of starting screening mammography no later than age 40 in African-American and Hispanic women. In addition, these women should have risk assessment for breast cancer no later than age 30 and be screened appropriately.

Keywords: Breast cancer, African-American, Hispanic, screening mammogram, palpable concern

Introduction

The most recent American College of Radiology (ACR) and Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) breast cancer screening guidelines recommend starting regular screening mammography at age 40, and recognize African-American women may be at a higher risk for developing breast cancer and should be evaluated for breast cancer risk no later than age 30 and screened according to their risk assessment1,2. However, the current United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines recommend biennial screening mammography for women ages 50-74 years that are at average risk for breast cancer and provide no specific guidelines for minority women3. The American Cancer Society (ACS) commissioned a systematic evidence review, and found that screening mammography in women ages 40-69 years is associated with a reduction in breast cancer deaths across a range of study designs4. Because the cumulative lifetime risk of false-positive examination results are greater if screening begins at younger ages, the ACS recommends women with an average risk of breast cancer to undergo annual screening mammography starting at age 45 years4. In fact, the recall rate of screening mammography is higher without prior mammograms, regardless of age5. Recent studies have found that digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) has resulted in a significant decrease in recall rates on screening mammography5-7. In addition, invasive cancers detected by DBT were more likely to be smaller and node negative when compared with cancers detected by two-dimensional (2D) digital mammography, particularly in women ages 40 to 49 years8. Thus, annual screening starting at age 40 is particularly important in the era of screening DBT. Moreover, malignancies in the 40-49 age range tend to be more aggressive, and thus, screening mammogram in this population leads to greater life years gained1, 2, 10. In addition, the ACR and SBI call for all women to have a risk assessment at age 30 to see if screening earlier than age 40 is needed1. Breast cancer risk assessment is critical to identify women who may benefit from more intensive breast cancer surveillance, and avoid applying average-risk screening recommendations to high-risk women9.

However, racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis, mortality, and survival persist in the U.S.10,11. African American and Hispanic women often experience delays in diagnosis and treatment as compared to white women, which negatively affects survival12-14. One study demonstrated that breast cancer mortality rates were 39% higher in African-American women than in white women15, and the median age for breast cancer-related deaths in white women was 69 years, but 62 years for African-American women10. African-American women are often diagnosed with breast cancer at a younger age and the disease tends to have a worse prognosis16,17. Population-based studies of cancer registries demonstrated that African-American and Hispanic women were diagnosed at a more advanced stage of breast cancer compared to white women, and had a higher incidence of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)16,18. Among women younger than age 44, population-based incidence rates of breast cancer are highest for African-American women16. In addition, Hispanic women were more likely to be under age 50 when diagnosed with breast cancer compared to white women18. Thus, early breast cancer detection via screening is particularly important for young African-American and Hispanic women. However, limitations in the national survey databases often lead to overestimations of mammography use, particularly among low-income racial and ethnic minorities19. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the diagnosis of breast cancer in the inner-city African American and Hispanic women by age, and to support the importance of screening in minority women under the age of 50. Our study was limited to the African American and Hispanic women, because our inner-city public hospital is located in an African American and Hispanic community as part of a public benefit corporation.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board, and granted a waiver of consent. The study was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

This retrospective study included all adult women who underwent screening and diagnostic mammograms from 1/1/2015 to 1/1/2019 in a public hospital mainly serving the inner-city minority population with limited access to care. Our hospital is part of a public benefit corporation located in an African American and Hispanic community in New York City. It mainly serves the inner-city poor and working class. Many patients are uninsured and do not speak English. We identified women newly diagnosed with breast cancer based on the tumor registration records of our Breast Imaging division. We excluded patients with prior history of breast cancer from the analysis, because they may be more aware of breast cancer and have different screening patterns.

The medical records of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer were reviewed. Demographics and clinical factors, such as age, race, presenting symptoms, imaging findings, pathologic findings, and risk factors were collected based on chart review. We also evaluated the screening pattern and incidence of TNBC in newly diagnosed women. We stratified the analysis by age groups to further evaluate the differences of having prior screening mammography, presenting symptoms and pathological findings by age.

Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for the analysis of categorical variables, while t-tests and One-way ANOVA were used for continuous variables. Significance was based on α<0.05 and all hypothesis tests were 2-sided. The analyses were performed using Stata version 16 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

Results

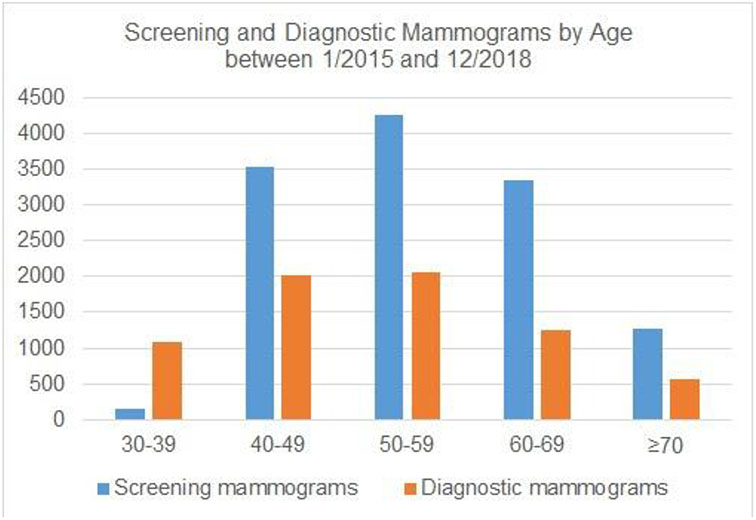

From 1/1/2015 to 1/1/2019, in women ages 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69 and ≥70 years, 148, 3529, 4264, 3352, and 1266 screening mammograms were performed respectively. Additionally, 1092, 2020, 2050, 1253, and 560 diagnostic mammograms were performed for the same respective age cohorts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Screening and Diagnostic Mammograms by Age between 1/2015 and 1/1/2019

We identified 115 women newly diagnosed with breast cancer from 1/1/2015 to 1/1/2019. The mean age at diagnosis was 59±14 years old, and the mean BMI was 30±7. Among them, 72/115 (63%) were African-American, 36/115 (31%) were Hispanic, and 7/115 (6%) were other races. 64% (74/115) of the women had invasive ductal carcinoma, 23% (26/115) had ductal carcinoma in situ, and 13% (15/115) had other histology as shown in Table 1. The average size of the mass on ultrasound is 3.14 cm for the 72 women who had a mass seen on ultrasound. Table 1 also shows all patient characteristics and clinical information by age groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and clinical information by age groups

| Total n (%) |

30-39 years old |

40-49 years old |

50-59 years old |

60-69 years old |

≥ 70 years old |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | 115 | 6 | 22 | 40 | 23 | 24 | |

| Race | |||||||

| Black | 72 (63%) | 4 (66%) | 14 (64%) | 24 (60%) | 14 (61%) | 16 (67%) | 0.863 |

| Hispanic | 36 (31%) | 1 (17%) | 6 (27%) | 13 (33%) | 8 (35%) | 8 (33%) | |

| Other | 7 (6%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (9%) | 3 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| BMI | 30±7 | 28±4 | 30±6 | 30±5 | 31±11 | 28±5 | 0.437 |

| Palpable concern with or without pain | 63 (55%) | 6 (100%) | 14 (64%) | 16 (40%) | 10 (43%) | 17 (71%) | 0.012 |

| Prior screening | 49 (43%) | 1 (17%) | 7 (32%) | 20 (50%) | 9 (39%) | 12 (50%) | 0.374 |

| Pathology | 0.647 | ||||||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 74 (64%) | 3 (50%) | 17 (77%) | 27 (68%) | 12 (52%) | 15 (62%) | |

| DCIS | 26 (23%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (9%) | 9 (22%) | 8 (35%) | 4 (17%) | |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 5 (4%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 0 | 2 (9%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Invasive mammary carcinoma | 4 (3%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 0 | 1 (4%) | |

| Invasive mucinous carcinoma | 4 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Invasive papillary carcinoma | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Malignant phyllodes tumor | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Triple negative (ER/PR/HER-2) | 17 (15%) | 1 (17%) | 5 (23%) | 6 (15%) | 2 (9%) | 3 (13%) | 0.619 |

We further restricted our analysis to African-American and Hispanic women who were newly diagnosed with breast cancer, and excluded women of other race from the analysis. Of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer, 60/108 (56%) were presented with a site of palpable concern with or without pain for diagnostic workup, and the remaining were diagnosed via asymptomatic screening. Women ages 30-49 were significantly more likely to present with a site of palpable concern when compared to women ages 50-69 (68% vs. 44%, p=0.045). Additionally, women ages 30-49 were more likely to have TNBC than women ages 50-69 (20% vs. 10%, p=0.222). However, women ages 30-49 were less likely to have prior mammogram than women ages 50-69 (24% vs. 46%, p=0.062). This could be because there are no current recommendations for average risk women aged 30-39 to have screening mammograms. In addition, women ages 30-49 were also more likely to present with larger size of mass on ultrasound when compared to women ages 50-69 (3.69 cm vs. 2.86 cm, p=0.431). We further analyzed the results by age groups (Table 2). There were statistically significant increased rates of women under 50 and over 70 years old presented with a site of palpable concern with or without pain, when compared to the other age groups (p=0.048). This trend is demonstrated in Figure 2. Only 45/108 (42%) women had at least one prior screening mammogram in the past 3 years in the US based on pre-exam clinical questionnaires, with decreased rates seen in younger age groups (p=0.190) as shown in Table 2. In our study, 71/108 (66%) women had invasive ductal carcinoma, with highest incidence seen in the 40-49 age group (p=0.826). Additionally, 14/108 (13%) women had TNBC, with higher incidence seen in younger age groups (p=0.818). This trend is demonstrated in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Characteristics and clinical information of African-American and Hispanic patients by age groups

| Total n (%) |

30-39 years old |

40-49 years old |

50-59 years old |

60-69 years old |

≥ 70 years old |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | 108 | 5 | 20 | 37 | 22 | 24 | |

| Race | |||||||

| Black | 72 (67%) | 4 (80%) | 14 (70%) | 24 (65%) | 14 (64%) | 16 (67%) | 0.958 |

| Hispanic | 36 (33%) | 1 (20%) | 6 (30%) | 13 (35%) | 8 (36%) | 8 (33%) | |

| BMI | 30±7 | 28±4 | 30±6 | 30±5 | 31±11 | 28±5 | 0.449 |

| Palpable concern with or without pain | 60 (56%) | 5 (100%) | 12 (60%) | 16 (43%) | 10 (45%) | 17 (71%) | 0.048 |

| Prior screening | 45 (42%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (30%) | 18 (49%) | 9 (41%) | 12 (50%) | 0.190 |

| Pathology | 0.826 | ||||||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 71 (66%) | 3 (60%) | 15 (75%) | 26 (70%) | 12 (55%) | 15 (63%) | |

| DCIS | 22 (20%) | 2 (40%) | 2 (10%) | 7 (19%) | 7 (32%) | 4 (17%) | |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 5 (5%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 0 | 2 (9%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Invasive mammary carcinoma | 4 (4%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 0 | 1 (4%) | |

| Invasive mucinous carcinoma | 4 (4%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Invasive papillary carcinoma | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Malignant phyllodes tumor | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Triple negative (ER/PR/HER-2) | 14 (13%) | 1 (20%) | 4 (20%) | 4 (11%) | 2 (9%) | 3 (13%) | 0.818 |

Figure 2.

Percentage of Women Presenting with Palpable Concern by Age among those Newly Diagnosed with Breast Cancer

Figure 3.

Percentage of Women Presenting with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Age

Discussion

In our study, only 24% of African-American and Hispanic women 30-49 years old reported having a prior mammogram, while 46% of African-American and Hispanic women 50-69 years old had a prior mammogram. Yet in our study, women ages 30-49 were more likely to present with a site of palpable concern and biologically aggressive malignancy. Varied screening recommendations can be a source of confusion for women1-4, causing delays of screening in women younger than ages 50. However, there currently is no recommendation for women with average risk for breast cancer to undergo screening mammography prior to age 40. The Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2019-2020 showed that, in 2015, 64% of women ages 40 and older reported having had a mammogram within the past two years20. However, only 49% of women 40-44 years old reported having had one within the past two years, compared to 69% and 68% in the 45-54 and ≥ 55 year old groups, respectively20. Our data suggests that for inner city minority women, these figures are even lower. Our results correlate with additional reports that uninsured women (31%) and recent immigrants (46%) reported the lowest prevalence of mammography use in the past two years20. Fear of cost is the most commonly perceived barrier to mammography amongst underserved women21. Disparities in screening mammography remains a problem among women of lower socioeconomic backgrounds and some racial/ethnic minorities19. Prior study of subgroups of Hispanic women has shown that patterns in mammography screening vary by insurance status and length of residency in the United States (US)22. Our study supports that the disparity in breast cancer screening is significant in young African-American and Hispanic women.

In our study, more than half of African-American and Hispanic women that were newly diagnosed with breast cancer presented with a site of palpable concern requiring diagnostic evaluation, with significantly increased rate in women ages younger than 50 and older than 70. This is likely because these inner-city minority women with limited access to care were not undergoing annual screening mammography. Studies have shown that African-American and Hispanic women experienced a longer time to breast cancer diagnosis than white women23, and African-American and Hispanic women were more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer23,24. African-American women had worse survival than white women18. In addition, the risk of death from stage I breast cancer was higher among African-American women than non-Hispanic white women 25. Moreover, population studies showed that Hispanic women have a higher risk of breast cancer mortality when compared to white women18. Meta-analyses of randomized, controlled trials demonstrate a 7%-23% reduction in breast cancer mortality rates with screening mammography in women ages 40-4926. There is also inferential evidence that supports breast cancer screening for women 70 years and older who are in good health4. However, the current USPSTF guidelines only recommend biennial screening mammography for average risk women ages 50-74 years old3, which is especially problematic for young African-American and Hispanic women. Thus, the new ACR and SBI breast cancer screening guidelines recommend starting regular screening at age 40, and recognize that African-American women are at higher risk for breast cancer2.

Our study also demonstrated 20% of malignancies diagnosed in the African-American and Hispanic women ages 30-49 were TNBC. In addition, over 60% of African-American and Hispanic women newly diagnosed with breast cancer had invasive ductal carcinoma, with the highest incidence of invasive ductal carcinoma seen in the 40-49 year age group. TNBC accounts for 15%-20% of all breast cancers27-29. It is associated with a worse prognosis, early relapse, higher frequency of metastasis, and low overall survival when compared to other breast cancer histologies27,29. It disproportionately affects BRCA1 mutation carriers and young African-American women. Additionally, African-American women with TNBC have worse clinical outcomes when compared with women of European descent27,29. Breast cancer in African-American women grows faster and is more likely to metastasize earlier than in white women30. Additionally, population study showed that Hispanic women also had higher rates of TNBC when compared to white women18. Given the aggressive nature of breast cancer in young African-American and Hispanic women, early risk assessment to identify women at higher risk would allow for referral for genetic counseling and testing, as well as patient counseling about risk-reduction options9.

Our study has several limitations. First, prior screening information was collected from clinical questionnaires completed by women prior to mammography. There could be recall bias regarding prior mammography. Even though the questionnaire has both English and Spanish versions, language barriers could also affect the accuracy of the responses, given the fact that our inner city public hospital serves immigrants in one of the largest cities in the US. In addition, although attempts were made to collect breast cancer risk factor data that may affect screening decisions, there was missing data, limiting further analysis of how breast cancer risk factors affect screening behavior. Thus, further analysis regarding how the presence or absence of these risk factors affect screening decisions could not be performed. Furthermore, socioeconomic factors, such as education, income, and immigration status, was not available in the electronic medical records to further evaluate the effects of these factors on breast cancer screening. Finally, many patients underwent breast cancer surgery, oncological treatment and follow up at different facilities after the initial diagnosis in our community hospital. Thus, we did not have breast cancer staging or tumor size based on surgical pathology, and could not adequately evaluate the treatment patterns and post-treatment outcomes of the patients.

In conclusion, young African-American and Hispanic women with newly diagnosed breast cancer under age 50 were more likely to present with a site of palpable concern, have no prior screening mammogram, and a higher incidence of invasive and TNBC when compared to those newly diagnosed patients ages 50-69. Our study highlights the importance of screening mammography in young African-American and Hispanic women who tend to have aggressive disease and poor outcomes. Our data support the ACR/SBI recommendations that breast cancer screening should start no later than age 40, and that African-American women may be at high-risk for breast cancer and should be evaluated for risk no later than age 30 and screened appropriately.

Highlights:

African-American and Hispanic women diagnosed with breast cancer < 50 years old were more likely to present with palpable concern and have no prior screening as compared to those diagnosed ≥ 50 years old.

These young minority women diagnosed with breast cancer < 50 years old were also more likely to have invasive and triple negative cancer as compared to those diagnosed ≥ 50 years old.

Our study highlights the importance of screening mammography in young African-American and Hispanic women < 50 years old who tend to have aggressive breast cancer.

Our data support the ACR/SBI recommendations that African-American women may be at high-risk for breast cancer and should be evaluated for risk no later than age 30 and screened appropriately.

Acknowledgments

VLM was funded in part by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. VLM reports funding from Pfizer for an unrelated study and is a consultant for Bayer Healthcare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The other authors have nothing to disclose.

References:

- 1.American College of Radiology and Society of Breast Imaging. New ACR and SBI Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines Call for Significant Changes to Screening Process. 2018; https://www.acr.org/Media-Center/ACR-News-Releases/2018/New-ACR-and-SBI-Breast-Cancer-Screening-Guidelines-Call-for-Significant-Changes-to-Screening-Process. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 2.Monticciolo DL, Newell MS, Moy L, Niell B, Monsees B, Sickles EA. Breast Cancer Screening in Women at Higher-Than-Average Risk: Recommendations From the ACR. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(3 Pt A):408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement Breast Cancer: Screening. 2016; https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-screening - :~:text=Recommendation%20Summary&text=The%20USPSTF%20recommends%20biennial%20screening,aged%2050%20to%2074%20years.&text=The%20decision%20to%20start%20screening,should%20be%20an%20individual%20one. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 4.Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk: 2015 Guideline Update From the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakim CM, Anello MI, Cohen CS, et al. Impact of and interaction between the availability of prior examinations and DBT on the interpretation of negative and benign mammograms. Acad Radiol. 2014;21(4):445–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sumkin JH, Ganott MA, Chough DM, et al. Recall Rate Reduction with Tomosynthesis During Baseline Screening Examinations: An Assessment From a Prospective Trial. Acad Radiol. 2015;22(12):1477–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carbonaro LA, Di Leo G, Clauser P, et al. Impact on the recall rate of digital breast tomosynthesis as an adjunct to digital mammography in the screening setting. A double reading experience and review of the literature. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85(4):808–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conant EF, Barlow WE, Herschorn SD, et al. Association of Digital Breast Tomosynthesis vs Digital Mammography With Cancer Detection and Recall Rates by Age and Breast Density. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(5):635–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Breast Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening in Average-Risk Women. 2017; https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2017/07/breast-cancer-risk-assessment-and-screening-in-average-risk-women. Accessed June 30, 2020.

- 10.DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Goding Sauer A, Kramer JL, Smith RA, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2015: Convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-figures.html. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 12.Gorin SS, Heck JE, Cheng B, Smith SJ. Delays in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by racial/ethnic group. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(20):2244–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGee SA, Durham DD, Tse CK, Millikan RC. Determinants of breast cancer treatment delay differ for African American and White women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(7):1227–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fedewa SA, Ward EM, Stewart AK, Edge SB. Delays in adjuvant chemotherapy treatment among patients with breast cancer are more likely in African American and Hispanic populations: a national cohort study 2004-2006. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4135–4141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeSantis CE, Ma J, Goding Sauer A, Newman LA, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2017, racial disparity in mortality by state. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(6):439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amirikia KC, Mills P, Bush J, Newman LA. Higher population-based incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer among young African-American women : Implications for breast cancer screening recommendations. Cancer. 2011;117(12):2747–2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohler BA, Sherman RL, Howlader N, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2011, Featuring Incidence of Breast Cancer Subtypes by Race/Ethnicity, Poverty, and State. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez ME, Gomez SL, Tao L, et al. Contribution of clinical and socioeconomic factors to differences in breast cancer subtype and mortality between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;166(1):185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peek ME, Han JH. Disparities in screening mammography. Current status, interventions and implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):184–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2019-2020. 2019; https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-prevention-and-early-detection-facts-and-figures/cancer-prevention-and-early-detection-facts-and-figures-2019-2020.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2020.

- 21.Fayanju OM, Kraenzle S, Drake BF, Oka M, Goodman MS. Perceived barriers to mammography among underserved women in a Breast Health Center Outreach Program. Am J Surg. 2014;208(3):425–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shoemaker ML, White MC. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Hispanic subgroups in the USA: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey 2008, 2010, and 2013. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(3):453–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, et al. Time to diagnosis and breast cancer stage by race/ethnicity. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(3):813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Li CI. Racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by hormone receptor and HER2 status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1666–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon PA, Sun P, Narod SA. Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(2):165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong K, Moye E, Williams S, Berlin JA, Reynolds EE. Screening mammography in women 40 to 49 years of age: a systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(7):516–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dietze EC, Sistrunk C, Miranda-Carboni G, O'Regan R, Seewaldt VL. Triple-negative breast cancer in African-American women: disparities versus biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(4):248–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Green AR, Lee AH, Robertson JF, Ellis IO. Prognostic markers in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(1):25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siddharth S, Sharma D. Racial Disparity and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in African-American Women: A Multifaceted Affair between Obesity, Biology, and Socioeconomic Determinants. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batina NG, Trentham-Dietz A, Gangnon RE, et al. Variation in tumor natural history contributes to racial disparities in breast cancer stage at diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(2):519–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]