Abstract

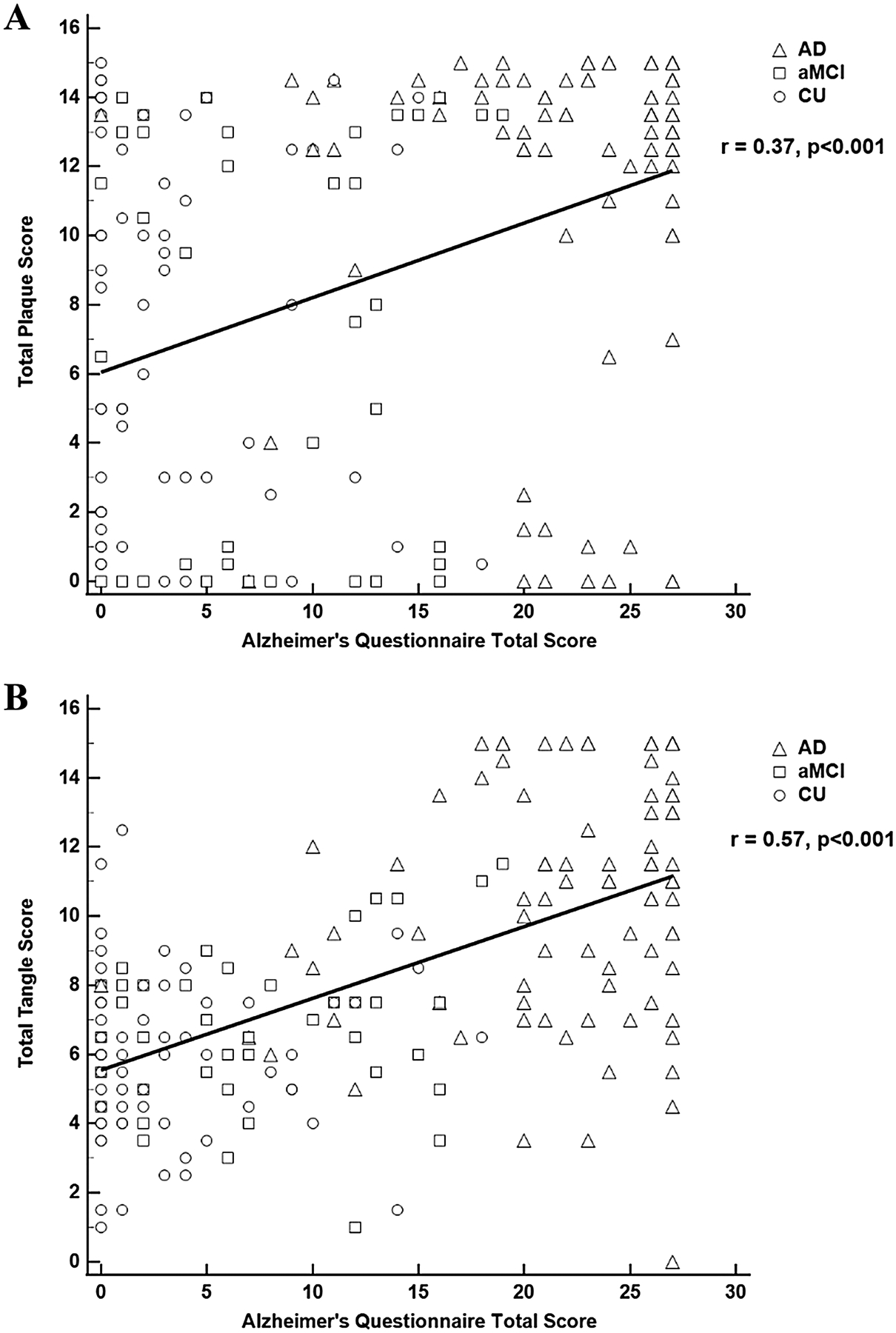

The Alzheimer’s Questionnaire (AQ) is an informant-based screening tool with good diagnostic accuracy for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI). The aim of this study is to validate the AQ with AD-associated neuritic plaque (NP) and neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) pathology. Data from 205 prospectively followed autopsy cases clinically classified as AD (n = 90), aMCI (n = 42), or cognitively unimpaired (CU, n = 73) were used. Semi-quantitative measures of NP and NFT pathology were correlated with the AQ, Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SOB), and the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE). The AQ correlated significantly (p < 0.001) with NP load (r = 0.37) and NFT load (r = 0.57). The MMSE and CDR-SOB showed similar correlations with NP load (r = − 0.37, r = 0.35, respectively) and NFT load (r = − 0.58, r = 0.55, respectively). The AQ correlates well with NP and NFT pathology of AD, which provides additional confidence to clinicians using the AQ to screen for AD-related cognitive impairment.

Keywords: Informant-based assessment, Dementia, Amyloid plaque, Neurofibrillary tangle, Neuropathology

Introduction

Informant-based reports of cognitive and functional status are key components of the diagnostic assessment for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), while structured instruments that assess informant-based reports of cognitive decline are often used as endpoints in AD clinical trials. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [1] has long been the gold standard for capturing changes in cognitive and functional status via informant reports, and antemortem CDR scores have been shown to correlate well with post-mortem measures of hallmark AD pathology [neuritic plaques (NPs) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs)] [2]. Since the time needed to administer the CDR prevents it from being used in most clinical settings, brief informant-based assessments have been developed to capture the core clinical symptoms of suspected cognitive decline. The AD8 is among the most widely used of these brief assessments and has shown to correlate well with imaging-based measures of AD pathology [3] as well as neuropathologically confirmed AD [4].

The Alzheimer’s Questionnaire (AQ) is an informant-based cognitive screening tool that has demonstrated good diagnostic accuracy for amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) and clinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [5]. We have previously shown that the AQ correlates well with established staging and screening measures of aMCI and AD (CDR, Mini Mental State Exam, Montreal Cognitive Assessment) [6], while more recent findings have shown that the AQ correlates well with PET-based amyloid load [7]. However, the AQ has not been correlated with post-mortem NP and NFT pathology and doing so would provide a more definitive validation that would complement the previous cognitive and neuroimaging validations [6, 7]. Thus, the aim of this study is to establish the AQ’s association with AD-related NP and NFT lesions.

Methods

Participants

Data included were from 205 individuals between the ages of 65 to 103 who were participants in the Brain and Body Donation Program (BBDP) [8] at the Banner Sun Health Research Institute, in Sun City, Arizona from 2011 to present. Although the BBDP has conducted over 1,800 autopsies since its inception, the AQ was added to the annual battery of clinical and cognitive assessments in 2011 so only a portion of those who came to autopsy have AQ data. Participants within the program are assessed annually with comprehensive neuropsychological and neurological exams. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrolling into the program.

Participants were categorized as cognitively unimpaired (CU), aMCI, and AD based on a consensus diagnosis determined by a neurologist and/or geriatric psychiatrist, and neuropsychologist using established diagnostic criteria [9, 10]. The consensus diagnosis was based on neurological and physical examinations, interviews, neuropsychological testing, and structured informant-based assessments of functional status, behavior, and mood. The Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) [11] and CDR Sum of Boxes (CDR-SOB) and Global CDR [1] were included in the annual assessments. AQ, MMSE, CDR-SOB, and Global CDR scores proximate to autopsy were used in the analyses.

Alzheimer’s Questionnaire

The Alzheimer’s Questionnaire (AQ) is a 21-item, informant-based dementia assessment designed for use in a primary care setting. The questionnaire is divided into five subsections, which include Memory, Orientation, Functional Ability, Visuospatial Ability, and Language. The sum of the yes/no questions equals a total AQ score (0–27), in which cutoffs for clinical classifications of CU (0–4), aMCI (5–14), and AD (≥ 15) can be utilized. Six items predictive of a clinical AD diagnosis are worth two points instead of one.

Neuropathological measures

NP and NFT loads were obtained by summation of separate semiquantitative density estimates of none, sparse, moderate, or frequent (converted to a continuous 0–3 scale for statistical purposes) using standardized published templates [12]. Regions scored included cortical gray matter from frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes, as well as hippocampal and entorhinal regions. Braak staging [13] was also used to quantify NFT severity and CERAD [12] scoring was used to quantify NP severity. Braak stage and CERAD scores were each condensed into three groups (Braak stages: 0-II, III-IV, V-VI; CERAD: None + Sparse, Moderate, Frequent) to facilitate categorical statistical analysis with the AQ’s clinical classifications of CU, aMCI, and AD.

Statistical analysis

The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to assess clinical group differences for numeric variables, while the Chi-square was used to determine between-group frequency differences for categorical variables. Spearman correlation was used to assess the unadjusted associations for the AQ, CDR-SOB, and MMSE with NP and NFT burden. Robust regression models were used to assess associations between the AQ, NP burden, and NFT burden while adjusting for age at death, sex, education, and apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 carrier status. Agreement between the AQ classification (CU, aMCI, AD) with consensus diagnosis (CU, aMCI, AD), NP severity, and NFT severity was assessed with a quadratic-weighted kappa statistic.

Results

Demographic, clinical, and neuropathological data for the three clinical groups are shown in Table 1. Age at death, years of education, and sex distribution did not differ significantly between CU, aMCI, and AD cases. The AD group had a significantly higher proportion of APOE ε4 carriers compared to the CU and aMCI groups (p = 0.003). The cognitive and neuropathological variables all differed significantly in the expected directions with the AD group having significantly worse cognitive performance and significantly greater NP and NFT pathology relative to the CU and aMCI groups. NP and NFT loads were not significantly different between the CU and aMCI groups.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and post-mortem characteristics stratified by clinical diagnosis

| CU (n = 73) | aMCI (n = 42) | AD (n = 90) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at death (years) | 87.07 ± 7.47 | 87.41 ± 7.64 | 86.91 ± 9.28 | 0.98 |

| Education (years) | 15.19 ± 2.73 | 15.00 ± 3.04 | 14.99 ± 2.95 | 0.72 |

| Sex (male/female) | 36/27 | 27/15 | 49/41 | 0.30* |

| APOE ε4 (carrier/non-carrier) | 17/56 | 6/35 | 36/51 | 0.003* |

| Clinical dementia rating sum of boxes | 0.39 ± 0.97 | 1.80 ± 1.34 | 12.14 ± 5.61 | < 0.001 |

| Mini mental state exam | 27.83 ± 1.61 | 25.68 ± 2.46 | 16.87 ± 7.43 | < 0.001 |

| Alzheimer’s Questionnaire | 2.93 ± 4.29 | 7.79 ± 5.79 | 22.24 ± 5.74 | < 0.001 |

| Post-mortem interval (hours) | 5.67 ± 9.10 | 4.67 ± 4.04 | 3.44 ± 2.30 | 0.03 |

| Duration between last clinical assessment and autopsy (months) | 12.75 ± 11.67 | 13.12 ± 10.54 | 21.88 ± 16.42 | < 0.001 |

| Braak Stage (I-II, III-IV, V-VI) | 9, 61, 3 | 2, 35, 5 | 1, 27, 61 | < 0.001* |

| CERAD neuritic plaque density (none, sparse, moderate, frequent) | 15, 16, 8, 34 | 11, 8, 3, 20 | 7, 4, 2, 76 | < 0.001* |

| Total tangle score | 5.59 ± 2.25 | 6.55 ± 2.23 | 10.32 ± 3.49 | < 0.001 |

| Total plaque score | 6.58 ± 5.56 | 6.07 ± 5.93 | 11.28 ± 4.71 | < 0.001 |

CU cognitively unimpaired, aMCI amnestic mild cognitive impairment, AD Alzheimer’s disease; mean ± standard deviation

Chi-square p value

The AQ correlated significantly with NP load (r = 0.37, p < 0.001; Fig. 1A) and NFT load (r = 0.57, p < 0.001; Fig. 1B). These associations remained significant after adjustments for age at death, sex, education, and APOE ε4 carrier status: AQ and NP, β = 0.28, 95% CI (0.21, 0.34), p < 0.001; AQ and NFT, β = 0.22, 95% CI (0.17, 0.28), p < 0.001. The AQ’s correlation with NP and NFT pathology was similar to that of both the CDR-SOB and MMSE where moderate correlations were noted (CDR-SOB*NP: r = 0.35; MMSE*NP: r = − 0.38; CDR-SOB*NFT: r = 0.55; MMSE*NFT: r = − 0.58). The level of agreement between the AQ clinical classification (CU, aMCI, AD) and consensus diagnosis (CU, aMCI, AD) was high [κ = 0.82, 95% CI (0.76, 0.88)]. However, the AQ clinical classification agreement with NP severity [None + Sparse, Moderate, Frequent] [κ = 0.24, 95% CI (0.12, 0.37)] and NFT severity [Braak 0–II, III–IV, V–VI] [κ = 0.51, 95% CI (0.43, 0.60)] was substantially lower.

Fig. 1.

Alzheimer’s Questionnaire correlations with plaque (A) and tangle (B) load

Discussion

The results of this study showed that the AQ correlates moderately with AD-related NP and NFT pathology. These associations remained significant after adjustment for demographic characteristics and APOE ε4 status and further demonstrate the AQ’s association with underlying AD pathology. The AQ’s agreement with ante-mortem consensus diagnosis was substantial, however, its agreement with NP and NFT classifications were not as robust which might be due to cognitive reserve in this highly educated cohort. Moreover, high levels of physical activity and social engagement are prevalent in this cohort and may also contribute to their levels of cognitive reserve which could further mitigate the development of cognitive decline associated with AD pathology. The AQ demonstrated fair agreement with NP severity and moderate agreement with NFT severity which suggests that AD-associated cognitive symptoms have a stronger association with NFTs relative to NPs. This trend is supported by the stronger correlation of AQ scores with NFT load (r = 0.57) relative to NP load (r = 0.37) and is consistent with previous reports that NFT lesions have stronger correlations with cognitive decline relative to plaque lesions [14]. Previous work has demonstrated that amyloid plaques have small, but significant, correlations with cognition [15] and the correlations between NPs and AQ scores reported here are consistent with those findings.

This study is limited by the ethnically homogenous sample of predominantly White individuals with high levels of education and as a result these findings may differ in samples with greater ethnic and socioeconomic diversity. An additional limitation is that other pathologies, such as vascular lesions, Lewy body disease, and TDP-43 were not used in these analyses. Since these (and other) pathologies may also contribute to cognitive decline in AD [14], the informant-reported symptoms of cognitive decline captured in the AQ may also be due to pathologies other than NPs and NFTs. In addition, these analyses did not account medical conditions that are thought to contribute to AD such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Despite these limitations, this study shows that the AQ reasonably correlates with AD-related NP and NFT pathology and allows clinicians to have greater confidence in the AQ’s performance when it is used to screen for AD-related cognitive decline.

Funding

The Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders and Brain and Body Donation Program has been supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30AG19610 and P30AG072980, Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None of the authors report any competing interests.

Ethical approval The Brain and Body Donation Program is approved by the Western Institutional Review Board.

Statement of human and animal rights All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrolling into the program.

Data availability

Data used in this study can be requested from the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program at (https://www.bannerhealth.com/services/research/locations/sun-health-institute/programs/body-donation/tissue).

References

- 1.Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurol 43:2412–2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Au R, Seshadri S, Knox K et al. (2012) The Framingham Brain Donation Program: neuropathology along the cognitive continuum. Curr Alzheimer Res 9:673–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galvin JE, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM et al. (2010) Relationship of dementia screening tests with biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 133:3290–3300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris GM, Holden TR, Weng H et al. (2020) Comparative performance and neuropathologic validation of the AD8 dementia screening instrument. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 34:112–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malek-Ahmadi M, Davis K, Belden C et al. (2012) Validation and diagnostic accuracy of the Alzheimer’s questionnaire. Age Ageing 41:396–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malek-Ahmadi M, Davis K, Belden CM et al. (2014) Comparative analysis of the Alzheimer questionnaire (AQ) with the CDR sum of boxes, MoCA, and MMSE. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 28:296–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunet HE, Miller JB, Shi J et al. (2019) Does informant-based reporting of cognitive symptoms predict amyloid positivity on positron emission tomography? Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 11:424–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI et al. (2015) Arizona study of aging and neurodegenerative disorders and brain and body donation program. Neuropathology 35:354–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M et al. (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurol 34:939–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC et al. (1999) Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 56:303–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res 12:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirra SS (1997) The CERAD neuropathology protocol and consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a commentary. Neurobiol Aging 18:S91–S94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82:239–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson PT, Braak H, Markesbery WR (2009) Neuropathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease: a complex but coherent relationship. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 68:1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedden T, Oh H, Younger AP et al. (2013) Meta-analysis of amyloid-cognition relations in cognitively normal older adults. Neurol 80:1341–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study can be requested from the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program at (https://www.bannerhealth.com/services/research/locations/sun-health-institute/programs/body-donation/tissue).