Abstract

Differentiated instruction (DI) is an inclusive method of instruction by which teachers provide multiple possibilities for learning based on students’ backgrounds, readiness, interests, and profiles. Acknowledging student diversity in Canadian classrooms, this study explores STEM teacher candidates’ (TCs’) preparation to implement DI in a STEM curriculum and pedagogy course in a teacher education program. The course is enriched with DI resources and training focused on equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI). The course efficacy in enhancing TCs’ implementation of DI is explored through the following research questions: (1) What is the impact of the course on TCs’ implementation of DI, (2) How do TCs develop curricula to be inclusive of DI strategies, and (3) What successes and challenges do TCs encounter when developing DI-focused curricula? The study adopts a mixed-method approach, in which data sources include pre-post questionnaires and semi-structured interviews. Participants are 19 TCs enrolled in the second year of the teacher education program at a Canadian university. Findings suggest that the course empowered TCs to integrate DI principles and strategies in their coursework. This success reiterates the importance of opportunities aimed at enhancing teachers’ preparation to incorporate DI in their practices. The findings call for adopting similar approaches in pre-service and in-service teachers’ training to ensure that DI principles and strategies are deeply rooted in teachers’ practices. The study informs teacher educators about integrating EDI in teacher education programs’ curriculum and overall planning.

Keywords: Differentiated instruction; Equity, diversity, and inclusion; STEM education; Science teacher education; Curriculum development; Reflective practice

Résumé

La différenciation pédagogique (DP) est une méthode d’enseignement inclusive selon laquelle les enseignants offrent plusieurs possibilités d’apprentissage en fonction du milieu dont sont issus les élèves, de leur réceptivité, leurs champs d’intérêts et de leurs profils. S’appuyant sur le fait qu’il existe une diversité d’élèves dans les salles de classe canadiennes, cette étude explore la préparation des aspirants enseignants (AE) des STIM à la mise en application de la DP dans un cours du curriculum et de la pédagogie des STIM au programme de formation des enseignants. Le cours est rehaussé par le biais de ressources en DP et d’une formation axée sur l’équité, la diversité et l’inclusion (EDI). On explore comment l’efficacité du cours peut servir à améliorer la mise en pratique de la DP par les AE à l’aide des questions de recherche suivantes: 1) Quel est l’impact du cours sur la mise en œuvre de la DP par les AE, 2) Comment les AE élaborent-ils des programmes qui intègrent les stratégies de DP, et 3) À quelles réussites et difficultés les AE font-ils face lorsqu’ils élaborent des programmes axés sur la DP ? L’étude adopte une approche méthodologique mixte, dans laquelle les sources de données comprennent des questionnaires « avant-après» et des entrevues semi-structurées. 19 AE inscrits en deuxième année du programme de formation des enseignants d’une université canadienne participent à l’étude. Les résultats indiquent que le cours a doté les AE de moyens d’intégrer les principes et les stratégies de la DP dans leurs travaux de cours. Cette réussite réitère l’importance d’avoir des occasions qui contribuent à améliorer la préparation des enseignants pour intégrer la DP dans leurs pratiques. Les résultats appellent à l’adoption d’approches similaires dans la formation initiale des enseignants et celle des enseignants sur place afin de s’assurer que les principes et les stratégies de la DP sont profondément enracinés dans les pratiques des enseignants. L’étude renseigne les formateurs d’enseignants sur l’intégration de l’EDI dans les programmes d’éducation des enseignants et dans la planification générale.

Introduction

Schools in Canada are well known for student diversity. One of the main reasons behind this diversity is the increase in the number of immigrants. For instance, the number of new immigrants who arrived in Canada between 2016 and 2021 was 1,328,240, with more than 450 ethnic or cultural origins existing in 2021 (Statistics Canada, 2022). According to Statistics Canada (2017), two in five Canadian children had an immigrant background in 2016, meaning they are foreign-born or had at least one foreign-born parent. By 2031, nearly half (46%) of Canadians aged 15 and older could have an immigrant background. These demographic factors also reflect diversity in socio-economic status (SES), cultural differences, and linguistic abilities.

Together, these societal changes directly affect the student composition of classrooms, rendering them very heterogenous spaces, especially when considering additional differences among students in their interests, individual needs, unique learning profiles, and academic achievement levels (Campbell, 2021; Tomlinson et al., 2003). Accordingly, curricula in Canadian classrooms are moving toward inclusive design, an approach that considers diversity with respect to students’ ability, language, culture, race, sexual orientation, creed, gender, and lived experiences (Malloy, 2019). Novel plans have been established across provinces to incorporate inclusive practices such as Ontario’s Education Equity Action Plan (2017) that supports school boards to develop equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) education policies and effectively implement classroom practices that “reflect the needs and diverse realities of all students” (p. 16). The plan hints at incorporating culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995, 2014) and culturally responsive teaching (Gay, 2010). Moreover, the plan aims to strengthen inclusive teaching, assessment, and resources, and provide professional development (PD) and support focused on equity and inclusion for teachers.

Despite these plans and policies, there remains much work to be done. Rezai-Rashti et al. (2015, 2017) highlight the invisibility of race and antiracism in Ontario’s policies and call for addressing the underlying structural and systemic imbalances. This outcome can be achieved through mechanisms that hold educational institutions accountable and provide the required resources to ensure the implementation of said policies. In harmony, the Ontario Ministry of Education reports that the recommended improvements did not fully provide equitable outcomes for all students, and further actions are required to overcome persistent systematic barriers, biases, and inequalities (Campbell, 2021). With respect to science education, Mujawamariya et al. (2014) critically analyze the content of Ontario’s science curricula for Grades 1 to 10 and maintain that small recent progress has been made to support multicultural science education. The authors highlight how antiracist content remains poorly integrated into Ontario science curricula, how minority students are excluded, and how the text is still dominated by a Western rather than an inclusive paradigm. In harmony, Madkins and Morton (2021) argue that teacher candidates (TCs) must be prepared to disrupt anti-blackness in science and mathematics education by developing their political clarity. Madkins and Morton define political clarity as the understanding of structural and school inequalities and engaging in equity-focused science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) teaching.

At the classroom level, the written organizational plans must identify the role of teachers and their responsibility in attending to the needs of their students. The literature recommends that teachers be more involved in the processes of improving inclusive curricula, materials, and their support for students (Tomlinson et al., 2003). Thus, it is fundamental to target the knowledge base of pre-service teachers as they embark on teaching careers in classrooms that reflect heterogeneous student populations. This measure will enable them to utilize transformative inclusive teaching strategies, such as differentiated instruction (DI) (Egbo, 2012). This research attempts to walk the EDI talk in schools by promoting TCs’ views, understandings, and implementation of DI as an equitable and inclusive teaching philosophy.

Research Rationale

Differentiated instruction is an adaptive method of instruction by which teachers provide multiple possibilities for learning based on students’ backgrounds, readiness, interests, and profiles (De Jesus, 2012; Tomlinson, 2001; Valiandes & Tarman, 2011). According to Tomlinson et al. (2003), the role of educators needs to focus on how to differentiate rather than if they should differentiate. Yet, the literature on DI shows lack of regular implementation by teachers in their classrooms (DiPirro, 2017; Robinson, 2017; Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010), thus providing additional rationale for the need to enhance teacher preparation in this regard. Additionally, research on DI implementation and teacher preparation in Canadian classrooms specifically is scarce despite the aforementioned context and policies (Whitley et al., 2019). Manavathu and Zhou (2012) maintain that the implementation of DI in Canadian classrooms faces many barriers. For example, they highlight how teachers feel unprepared to accommodate English language learners (ELLs) and how ELLs are less likely to enroll in senior biology courses due to the language complexity. Accordingly, Manavathu and Zhou call for the development of linguistically appropriate science course materials and consideration of students’ individual sociopsychological influences to enhance their science learning. Additionally, D’Intino and Wang (2021) emphasize that Canadian teachers need more support to be able to differentiate their instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Specht et al. (2016) indicate the specific need for secondary school level TCs’ training on inclusive teaching strategies, since they show lower self-efficacy in relation to inclusive teaching compared to their elementary school counterparts. Finally, DI applications in STEM education at the secondary school level are limited, since most of the research has been conducted on DI in languages and mathematics for primary and middle school (Kamarulzaman et al., 2018; Maeng, 2017). Thus, the current research is warranted as it addresses teacher education in Ontario, specifically how to differentiate instruction by engaging TCs in developing DI-focused STEM curricula.

Research Objectives and Questions

This research focuses on intermediate-senior STEM TCs’ teacher preparation, with an emphasis on their implementation of DI. The study highlights the impact of integrating DI-focused strategies in a STEM curriculum and pedagogy course in teacher education at a Canadian university by addressing the following questions:

What is the impact of the course on TCs’ implementation of DI?

How do TCs develop curricula to be inclusive of DI strategies?

What successes and challenges do TCs encounter when developing DI-focused curricula?

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Methods to Differentiate Instruction: CPP-RIP Framework

Differentiated instruction is not a single strategy but rather an approach that affords many strategies (Watts-Taffe et al., 2012). Establishing a systematic approach to differentiation is important to make it more attainable for teachers to implement (Levy, 2008). In practice, DI can happen through modifying the content (what is taught), process (how learning is structured), and product (how learning is assessed), in addition to the physical learning environment (Tomlinson, 2001). These modifications are achieved through adaptation of the existing curriculum, development of lessons and resources, and implementation of teaching and assessment strategies (Beasley & Beck, 2017; Mitchell & Hobson, 2005; Tomlinson, 2014; Willis & Mann, 2000).

The content—knowledge, understanding, and skills—is what students are expected to learn. The process describes the methods designed throughout the lesson to reinforce students’ understanding of the content. The product refers to how students demonstrate their learning by means of assessment tools. It is how students show what they have come to know, understand, and are able to do after an extended period of learning (Tomlinson, 1999; Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). It is important to mention that these dimensions of DI are highly interconnected rather than independent (Watts-Taffe et al., 2012). Although there are core principles that guide the use of DI, its implementation depends on the individual needs of students in a particular classroom (Chamberlin & Powers, 2010). Tomlinson et al. (2003) indicate that when teachers differentiate the content, process, and product of teaching, three main factors must be considered as the basis of this differentiation: (1) students’ readiness which mainly reflects academic achievement levels, (2) students’ interest or choices, and (3) students’ learning profiles including their cultural backgrounds and lived experiences. This DI implementation framework, the content, process, product – readiness, interests, profiles (CPP-RIP) is utilized in this paper to analyze TCs’ implementation of DI.

Despite the fact that there is no single formula or method to apply DI (Valiandes & Tarman, 2011), specific teaching strategies include varying the learning pace for different students, curriculum compacting and chunking, varying the difficulty levels of tasks for different students, flexible grouping and learning centers based on student interests and/or learning needs, cooperative learning strategies, tiering activities, providing various levels of support and scaffolding to different students based on their readiness, using different modalities of teaching, and utilizing formative and diagnostic assessments to keep track of students’ progress (Birnie, 2017; Blackburn, 2018; Tomlinson et al., 2003). In conclusion, the hallmark of differentiating instruction is that it allows students to feel accepted by viewing their differences as assets that will strengthen the whole educational setting (George, 2005).

Teachers’ Implementation of DI

The literature on teachers’ implementation of DI reports that most teachers are aware of the practice, but many do not regularly implement it in their classrooms (DiPirro, 2017; Niccum-Johnson, 2018; Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). Niccum-Johnson (2018), for example, evaluated the consistency of 175 elementary teachers in Illinois in implementing DI. The results showed that only 60% of the teachers consistently used the elements of DI. Moreover, the study noted that teachers with a bachelor’s degree implemented DI more consistently than those with a master’s degree, while the years of experience had no effect. Robinson (2017) contradicted this inference and concluded that new teachers practiced the operational definition of DI more closely than veteran teachers who integrated DI into their daily activities more often. Santangelo and Tomlinson (2012) demonstrated that teacher educators did not implement a comprehensive model of differentiation. In line with this finding, Kendrick-Weikle (2015) stated that teachers differentiated the process component of their instruction, but they did not differentiate the contents and the products to the same extent. The study also noted that female teachers and teachers in larger schools were more familiar with DI and used accompanying strategies more often than male teachers, and teachers at smaller schools, respectively.

On the other hand, the implementation of DI in Canadian classrooms, especially in Ontario, is insufficiently researched. Limited studies exist, with most of the research conducted in Quebec and published in French (e.g., Moldoveanu et al., 2016; Paré & Prud’homme, 2014; Prud’Homme, 2007). Research has also been conducted with French language teachers (Guay et al., 2017; Roy et al., 2013) to support inclusion practices in Quebec, and in music classes (Kizas, 2016) and language arts in elementary schools in British Colombia (Tobin, 2007). Finally, a study conducted in elementary classrooms in Ontario showed that the instructional practices in public schools appeared to be cumulative rather than differentiated and that academically at-risk students received less DI than others (McGhie-Richmond et al., 2007).

Wan (2016) highlights that differentiating instruction is more complex in reality than it appears. Teachers could not cater to learners’ diversity as seamlessly due to the lack of practice utilizing differentiation strategies. Teachers in the study were afraid that differentiating, particularly assessment, was not fair to students in an exam-oriented environment. These findings reiterate the importance of teachers’ readiness and preparation to practice DI frequently and proficiently.

Challenges to Implementing DI

Several challenges that hinder teachers’ implementation of DI are documented, including (1) curricular requirements; (2) extensive teacher workload and lack of time; (3) limited curriculum resources; (4) lack of administrative support; (5) perceived complexity and difficulty; (6) class size and individual needs of students; and (7) insufficient number and quality of PD programs (de Jager, 2017; Park & Datnow, 2017; Turner & Solis, 2017; Wan, 2017). To capture the complexity of differentiating instruction, van Geel et al. (2019) use the cognitive task analysis to show what kind of knowledge and constituent skills are needed to be able to adapt instruction to the needs of the students. The results of the research identify six categories of teacher skills: (1) mastering the curriculum; (2) identifying instructional needs; (3) setting challenging goals; (4) monitoring and diagnosing student progress; (5) adapting instruction accordingly; and (6) general teaching dimension. This model serves as the basis for designing curricula and teacher PD initiatives. Moreover, research has shown the necessity and importance of PD initiatives for pre-service (Dack, 2018; Goodnough, 2010) and in-service teachers (Dixon et al., 2014; Nicolae, 2014; Pincince, 2016) to enhance their self-efficacy, understanding, and implementation of DI (e.g., Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021; Maeng, 2017; Nicolae, 2014; Paone, 2017; Rollins, 2010; Taylor, 2018; Wertheim & Leyser, 2002).

Correspondingly, research on exemplary differentiated STEM resources is scarce especially at the secondary school level. Thus, the aforementioned challenges of available curriculum resources, required time, and perceived difficulty are justified. This study addresses those challenges and the lack of PD related to DI. In this study, TCs engaged in designing and developing differentiated curriculum materials in STEM subjects. Successes and challenges of similar teacher preparation initiatives to enhance TCs’ familiarity and implementation of DI are highlighted. Additionally, specific strategies to differentiate instruction in secondary STEM classes are showcased.

Reflective Practice

Pollard and Tann (1997) describe reflective teaching as how teachers investigate their practice. Farrell (2015) defines reflective practice as “a cognitive process accompanied by a set of attitudes in which teachers systematically collect data about their practice, and while engaging in dialogue with others, use the data to make informed decisions about their practice” (p. 123). Hubball et al. (2005) maintain that when teachers engage in reflective practice, they question what they do, what works and what does not, and what rationales underlie their teaching and that of others. In harmony, Brantley-Dias et al. (2021) emphasize the crucial role of reflection in professional growth. By reflecting, teachers or TCs would engage in a cognitive process in which they understand an experience and make informed decisions for new actions. In this study, TCs engaged in reflective practice by reflecting on their actions consistently throughout the course. TCs reflected on various concepts throughout their learning as well as on each assignment they developed. Combined with feedback provided by their peers and the instructor, the study highlights how these forms of reflective practice contributed to their views, conceptions, and implementation of DI.

Methodology

Research Design

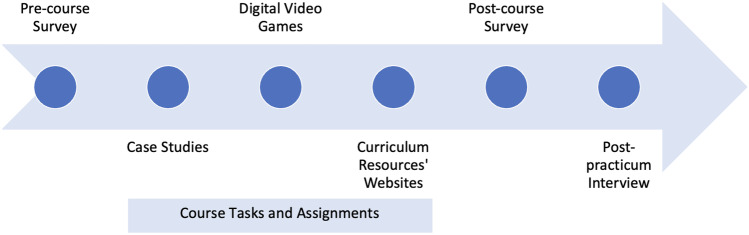

The study adopted a mixed-method approach (Creswell & Creswell, 2018), specifically a case study (Yin, 2014). Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. Data sources include (1) pre- and post-course surveys exploring TCs’ views, understandings, and implementation of DI; and (2) semi-structured interviews detailing TCs’ implementation of DI in the course and in their practicum. Figure 1 summarizes the timeline of the course, and data sources and collection.

Fig. 1.

Course components and data collection timeline

Participants

A total of 19 TCs (9 males; 10 females) participated in the study. Participants were enrolled in a STEM Curriculum and Pedagogy course in the second year of the teacher education program at a university in Ontario, Canada. All TCs teach STEM subjects in the intermediate-senior divisions (Grades 9, 10, 11, and/or 12), including general sciences, biology, math, physics, chemistry, health and physical education, and computer studies. In terms of educational background, three TCs have a master’s degree while 16 TCs hold a bachelor’s degree.

Overview of the Course Design

Differentiated instruction principles and strategies were integrated through seminars, assignments, and resources using an explicit and reflective approach (Abd-El-Khalick & Lederman, 2000). In the first session of the course, TCs’ prior understandings and views of DI were gauged through an online survey and a few diagnostic activities, including prompts using interactive presentation tools. Afterwards, in the first 2 weeks of the course, the course instructor collaborated with the researcher to provide a seminar on DI and EDI. Throughout the 12-week course, the instructor provided the TCs with resources to integrate DI and included tailored tasks requiring the application of DI principles and strategies, without changing the nature of the tasks that had been already planned for this course (DeCoito, in press). As such, TCs completed three major curriculum development projects: (1) creating case studies around socio-scientific issues (SSI) (DeCoito & Fazio, 2017), (2) developing digital video games (DVGs) (DeCoito & Briona, 2020; Estaiteyeh & DeCoito, 2023), and (3) creating digital curriculum resources websites (DeCoito & Estaiteyeh, 2022).

TCs were requested to explicitly address DI in their coursework. Assignment rubrics included effective integration of DI as one of the success criteria. The instructor and researcher provided feedback on TCs’ work on a regular basis by recommending how to improve or maintain certain aspects of their assignments. TCs were also engaged in constant reflections on their progress and hence advancing their knowledge and skills in DI implementation throughout the course. Moreover, TCs presented their work to their peers, and provided and received peer feedback.

Data Sources

Surveys

The pre-survey, composed of five open-ended questions, was administered online on the first day of the course. This survey explored TCs’ views and prior preparation with respect to DI. The post-survey, administered online on the last day of the course, included 43 5-point Likert scale items (1 = strong disagreement to 5 = strong agreement) and four open-ended questions. It explored TCs’ understanding and implementation of DI in the course, and their evaluation of the effectiveness of the course with respect to DI.

The Likert scale items were adopted from surveys (Roy et al., 2013; Santangelo & Tomlinson, 2012) that were tested for content validity and reliability. Santangelo and Tomlinson’s (2012) survey addressed teacher educators’ perceptions and use of DI practices, whereas Roy et al.’s (2013) DI scale included items related to instructional adaptations and assessment strategies in DI. On the other hand, the open-ended questions in both the pre- and post-surveys were developed by the researcher based on the research questions, the course tasks, and the literature. In total, 19 consenting TCs completed the pre-survey and 17 of them completed the post-survey.

Semi-structured Interview

Two months after the course ended, TCs were invited to participate in a 1-hour semi-structured online interview to follow-up on their responses in the pre/post-surveys and their course work. The interview explored in greater depth certain elements of the survey and course work, such as details of how TCs understood and implemented DI, and/or how they would implement it in their future practices. This interview was used to clarify, detail, and increase the trustworthiness of the other data sources. In total, six TCs participated in the interview.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data from the surveys were analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics were performed including calculating counts, averages, standard deviations, percentages, and differences between pre- and post-results. Additionally, inferential statistical tests were performed using SPSS. The Spearman correlation test was performed to explore the relationship between different ordinal variables, i.e., different 5-point Likert items (Connolly, 2007). On the other hand, qualitative data from open-ended survey questions and interviews were analyzed using an inductive process for some questions and a deductive process for others (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The inductive analysis builds patterns, categories, and themes by organizing the data into more abstract units of information (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Participants’ responses were inputted into NVivo 12 where initial codes were developed using word clouds based on the frequency of words in TCs’ responses. Subsequently, the codes were grouped into themes, finalized, and interpreted to draw conclusions (Gall et al., 2005). Thematic coding (Stake, 2020) was performed to provide an in-depth analysis of the responses of all participants, which was used later to calculate the frequency of responses in relation to each theme. This inductive process was used to analyze responses related to TCs’ prior preparation and challenges encountered. On the other hand, responses related to how TCs implemented DI were analyzed deductively according to the CPP-RIP framework explained earlier.

Results and Discussion

TCs’ Prior Preparation

Participants were asked about two specific documents to understand TCs’ prior exposure to important policy publications about EDI and DI issued by the Ministry of Education in Ontario. One out of 19 TCs indicated that they had read the Education Equity Plan (2017), while three out of 19 TCs indicated reading the Differentiated Instruction handbook (EduGains, 2010) and/or its accompanying online resources.

Furthermore, to explore TCs’ readiness and prior preparation, they were asked in the pre-survey to reflect on any PD they have had that would assist them to teach through an EDI lens in their classes and to evaluate the effectiveness of these PD opportunities. Out of 15 respondents, eight TCs stated specific coursework that included EDI-related topics such as Indigenous education, special and inclusive education, or/and STEM methods course in year 1 of the program. Five TCs noted that their year-1 practicum experience helped them explore EDI principles and applications. On the other hand, three TCs mentioned specific PD workshops related to the topic. Concerning the effectiveness of the above opportunities in helping them teach through an EDI lens in the future, ten TCs responded, with six of them agreeing that these opportunities were effective and four stating they were not. Out of the six TCs who indicated their experiences were effective, four mentioned the practicum to be specifically helpful. This finding highlights that TCs’ exploration of the concepts of EDI and DI mostly happens in a practical way in their practicum rather than in their courses or through additional PD. On the other hand, the four TCs who said that their experiences were not effective in helping them teach through an EDI lens pointed out that what they learned was irrelevant to their specific classes:

The strategies I learned for differentiated instruction were largely inapplicable to my most recent practicum, or at least I was ill-prepared for translating them to an online environment. (Gabe, Pre-survey)

It would be more effective to see them (the strategies) in action in real life. (Jan, Pre-survey)

The reasons for this (ineffectiveness) were the “busy work” associated with the special education course and the emphasis on elementary education. I am a high school teacher candidate. (Roy, Pre-survey)

Teacher candidates' responses on the interview at the end of the study corroborated these pre-survey findings. All six interviewees stated that they had experienced a form of DI in their coursework and/or teaching prior to the STEM curriculum and pedagogy course. Five of them mentioned taking courses related to DI (two of which mentioned special education courses), while four TCs said they had experienced DI in their practicum. Yet, five of the interviewees indicated that this exposure to DI was not quite effective. For instance, Roy said:

Before, I had the first practicum experience. And I did not add actually as much differentiated instruction. I had some that I implemented being like, just introductions of like videos for English language learner students, in addition to other course content but that was mainly guided by my associate teacher rather than it was my own. Some of the courses touched on it. We had a course on special education, touch on differentiation... We also had an Indigenous education course which touched on it briefly, although like in all of them it’s not super super in depth I believe in the ways you do it, it’s more just, we learned like what it is, to look at how we could apply it… (Roy, Interview)

These findings illustrate that TCs had varying levels of exposure to DI principles in some of their courses and their practicum experiences. Yet, the effectiveness of these opportunities is debatable. As argued by some TCs, the previous courses did not provide STEM-specific and high school–specific skills. Moreover, the emphasis on DI in mostly special education courses reinforces teachers’ misconception that implementing inclusive practices such as DI is only for students with exceptionalities (DiPirro, 2017; Whitley et al., 2019). This notion defeats the goal of integrating DI under all circumstances. On the other hand, practicum experiences, referred to by the majority of TCs, are related to the environment of specific schools and the efforts of specific mentoring teachers, and hence are not consistent among all TCs. Finally, most TCs have not read the Ministry published documents which suggests that programs need to work on this aspect as the documents are designed for the context of Ontario schools. The lack of engagement of TCs with the documents also reflects a gap between policy and practice. Overall, the preparation of TCs for DI requires improvement so that they consistently acquire specific knowledge and skills that enable them to utilize DI principles and strategies in teaching STEM subjects in Ontario classrooms.

These results also reiterate to a certain extent D’Intino and Wang’s (2021) findings from the theoretical analysis of the coursework offered in Canadian universities, indicating that the current coursework is not sufficient to prepare TCs for DI. Findings also corroborate Massouti’s (2019, 2021), Rezai-Rashti and Solomon’s (2008), and Specht et al.’s (2016) conclusions related to the need for enhancing TCs’ preparation focusing on EDI practices in teacher education programs in Canada. Moreover, the fact that the majority of TCs were referring to DI based on their practicum experience highlights the importance of practical fieldwork and calls for further coherence between coursework and the practicum (Dack, 2019; Massouti, 2019).

TCs’ Reflection on their DI Implementation

In the post-survey, TCs reflected on their implementation of DI in the course tasks. Figure 2 shows the percentages of TCs who agreed or disagreed with various statements regarding their DI implementation. Most TCs agreed that their DI implementation was extensive (13 out of 17 TCs). The vast majority of the TCs indicated that they (1) differentiated the content (15 out of 17 TCs) by offering choices, extending the knowledge of advanced learners, providing support to students with difficulty, presenting the content at varying levels of complexity, reflecting students’ interests, eliminating curricular material for some students, and adjusting the pacing of instruction; (2) differentiated the process (15 out of 17 TCs) by offering multiple modes of learning, varying the instructional strategies, using flexible grouping, using independent study, and using interest centers; and (3) differentiated the product (16 out of 17 TCs) by varying the types of assessments, providing students with choices to express their understanding, providing tiered assignments, and utilizing rubrics that match varied ability levels.

Fig. 2.

TCs’ post-survey responses on DI implementation in the course (n = 17)

Most TCs agreed that they allow students to play a role in designing/selecting their learning activities (14 out of 17 TCs) and assessing their own learning (13 out of 17 TCs). The majority of TCs agreed that they use diagnostic assessment (14 out of 17 TCs), formative assessment (16 out of 17 TCs), and summative assessment (16 out of 17 TCs); and that these assessments inform subsequent teaching (all 17 TCs). Fifteen out of 17 TCs stated that they evaluate the effectiveness of their teaching adjustments, while 14 of them stated that they evaluate students based on their improvement and growth during the semester with respect to their initial academic levels. Finally, on the use of technology, 16 out of 17 TCs stated that they use technology as a tool for DI, and 14 out of 17 TCs stated that they use technology for assessment in DI specifically. Overall, the results show high levels of TCs’ implementation of DI in all aspects. This finding highlights the positive impact of the course on TCs' pedagogical skills related to DI, and hence an adequate preparation of teachers to implement EDI principles in their future classes. These findings parallel the literature on the importance and positive impact of teacher training on DI understanding and implementation for both pre-service and in-service teachers (Dixon et al., 2014; Goodnough, 2010; Nicolae, 2014; Pincince, 2016).

To investigate further, results of the Spearman correlation test indicate the relationship between TCs’ level of DI understanding and their implementation in the course work. For example, the post-survey results indicate a significant positive correlation between TCs’ familiarity with at least three methods to differentiate the content and their implementation of at least three methods of content differentiation in their course work (rs = 0.62, p = 0.009). Additionally, results of the Spearman correlation indicate a significant positive correlation between TCs’ familiarity with at least three methods to differentiate the process and their implementation of at least three methods to differentiate the process in their course work (rs = 0.69, p = 0.002). Similarly, results of the Spearman correlation indicate a significant positive correlation between TCs’ familiarity with at least three methods to differentiate the product and their implementation of at least three methods to differentiate the product in their course work (rs = 0.72, p = 0.001). These findings reiterate the positive correlation between TCs’ understanding of DI and its implementation (DiPirro, 2017; Suprayogi et al., 2017; Whitley et al., 2019).

TCs’ Incorporation of DI Strategies in Their Coursework

Teacher candidates described in the interview how they differentiated instruction in their course work. TCs elaborated on how they differentiated the content, the process, and the product. TCs also discussed how they attended to EDI aspects especially respecting diverse cultural backgrounds, genders, and non-Western views. Furthermore, in the post-survey TCs indicated which assignment(s) in the course was/were the most relevant for differentiating instruction—nine out of 13 TCs selected the curriculum resources websites, four TCs stated the case studies, and two specified the DVGs. One TC, Erin, said it was all three assignments:

Every lesson and assignment created is relevant to differentiate instruction. I achieved through offering choices, extending knowledge of advanced learners, providing supplemental support, reflecting student’s interests, etc. (Interview)

Teacher candidates described their ability to develop resources that are inclusive of DI strategies and reflected positively on the various tasks:

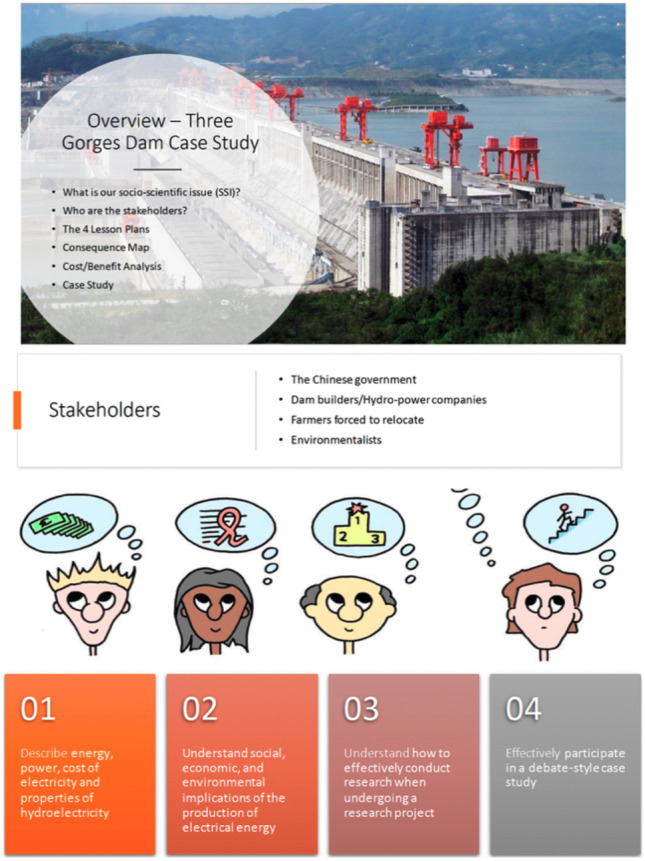

Case Studies

In the first assignment, TCs developed curriculum by creating case studies of SSI (Fig. 3). TCs demonstrated proficient integration of DI principles, with TCs differentiating the process most, followed by the product of learning yet showing a need for more training in content differentiation in order to attend to students’ needs, backgrounds, and academic levels.

Fig. 3.

Sample cover page of a case study about hydroelectricity

In the interview, TCs explained how they developed case studies, taking different perspectives on the SSI into consideration, how they prepared materials with varied difficulty and readability levels, and how their lesson plans included multimodal teaching strategies. TCs said:

I made sure to incorporate lots of different levels of readings for my students so if I was assigning an article, I made sure that I checked out what reading level that article was and gave different levels and different options. And I also included a lot of different perspectives. And, like, we looked at issues on different scales so not just local, but also on a global scale. So, that was good! (Erin, Interview)

We tried to do it (the case study) through different modes of learning and assessment. We used like a forum, kind of setting for our assessment where students would talk to each other, and they’d like exchange ideas. Specifically, always tried to use different methods of teaching, not just like direct instruction but also a collaborative group work, think pair share, stuff just different ways for students to augment their understanding. (Michael, Interview)

On the relevance of case studies for differentiating instruction, TCs said:

The case study was the most relevant to me for differentiated instruction. The various ways to conduct research (KWL, Cornell framework, consequence map, etc.) are all useful tools that can benefit different learners and providing students with these resources can assist them in conducting research in ways that work for them. (Gabe, Post-survey)

I believe the case study assignment was the most relevant to differentiate instruction. We did this through offering multiple ways for students to engage with the content and complete their assignments. (Roy, Post-survey)

Digital Video Games (DVGs)

TCs developed DVGs with a simultaneous focus on DI and technology-enriched resources (Fig. 4). In differentiating the content, DVGs included increasing levels of difficulty highlighting scaffolding and varied pacing based on students’ readiness levels. In terms of process differentiation, the DVGs included multimodal representations; yet they are to be combined with other teaching strategies to ensure adequate differentiation. In terms of product differentiation, DVGs offered the room for diagnostic assessment before the game commences through guided questions as well as formative assessments and feedback throughout the levels. Additionally, the DVG offered space to represent various students’ backgrounds, genders, and physical abilities through avatars incorporated in the game.

Fig. 4.

Sample DVG focusing on physics concepts—projectile movement

In the interviews, TCs explained how their DVGs were culturally relevant, and how their avatars were inclusive in nature. Moreover, they explained how the levels included in the game were suitable for addressing students’ varying academic achievement levels. TCs said:

I had concepts outlined in different ways and had students use the visual stimulus from the pictures on the periodic table. But not just differentiated instruction, I also had diversity and equity through descriptions of elements in the periodic table. I had the related cultural backgrounds in there. (Roy, Interview)

I incorporated like a more universal approach by giving students the options to like to choose their avatars, and the gender of their avatar. (Erin, Interview)

There are different settings for video game for different capabilities of students depending on where their levels were. (Michael, Interview)

On the relevance of DVGs, Robert said:

DVG (was the most relevant to DI due to its) differing levels of difficulty. (Post-survey)

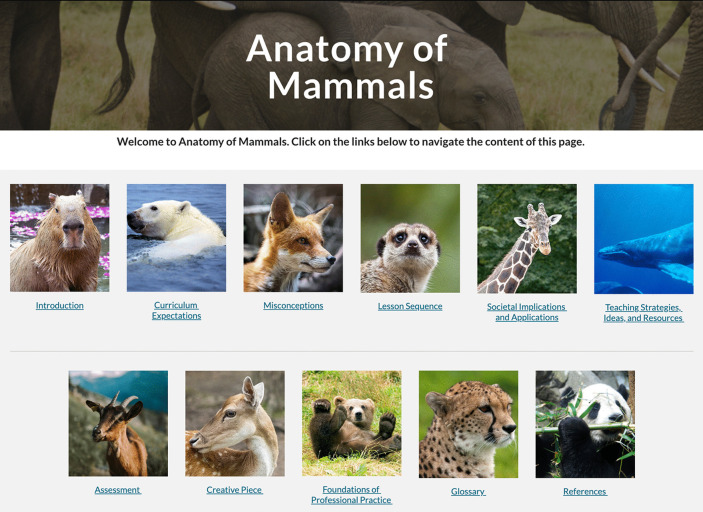

Curriculum Resources Websites

In the curriculum resources’ websites (Fig. 5), TCs showed adequate to high inclusion of DI principles and strategies utilizing a wide array of creative tools. TCs’ work demonstrate that they were able to prepare lessons and compile numerous resources while integrating a DI framework. TCs addressed common student misconceptions, acknowledged students’ prior knowledge, utilized a wide variety of multimodal teaching strategies, and included various forms of diagnostic, formative, and summative assessment methods. TCs addressed student differences in academic achievement levels, interests, cultural backgrounds, SES, linguistic abilities, and special needs. TCs were also capable of linking their science topics to equity matters and social justice issues by highlighting real-life-related scenarios. In agreement with the analysis of their course work, the majority of TCs stated in the post-survey that the curriculum resources’ website assignment was the most relevant to differentiate instruction when compared to other assignments.

Fig. 5.

Sample of a STEM curriculum website content page

TCs explained in the interviews how they created new digital resources and amalgamated available materials, while taking DI into consideration. Their resources are multimodal, reflect students’ cultural diversity, cater for different academic and linguistic levels, and integrate technology effectively. TCs said:

I just included research from different countries, so we’re not just focusing on North America, but we also talked about research focusing on Asia and also focusing on Europe. I also included resources where females are talking about their experiences in STEM or their experience in the field. For the lesson plans, students research about different cultures and countries in term of medicine, technology… I tried to reflect just not just the North American view. (Pam, Interview)

For those resources, I just made sure like I had good lots of options to my students like I incorporated something called a RAFT project so students could choose the role and the audience, and the format, that kind of thing for all their assignments that they were submitting, And I also made sure that I was delivering the content in different ways. So, like I said before I was making sure I just had a PowerPoint but, in this case, I had different ways to show the learning through like live demos or incorporating technology like Ozobot. So, they had multiple ways to join the classroom learning. (Erin, Interview)

I did like a whole bunch of assessments that were differentiated, not just tests but also interesting assignments so fairly open ended that allowed students to showcase how they learned in a way that was comfortable for them, and also teaching in ways that weren’t just the direct instruction with using videos and demonstrations and group activities. (Michael, Interview)

On the relevance of the STEM curriculum websites, TCs said:

The curriculum resource assignment was the most relevant. I made sure to include a variety of instructional modalities, teaching strategies, and active learning strategies in my lesson plans. I made sure to incorporate EDI into my lessons, accommodate for different learning styles, as well as providing visual support in lesson materials. (Holly, Post-survey)

For me, it is the curriculum resource website. Because it integrates all the DI through the whole package, that is, initiatives, motivations, lesson plans, activities and assessments. (Nellie, Post-survey)

Curriculum resource website- developing resources and lessons lends itself to differentiated instruction more easily than specific tasks. (Jim, Post-survey)

Curriculum resources website- accumulating a variety of resources that can be used to achieve different goals and support UDL/DI in the classroom. (Elizabeth, Post-survey)

Curriculum resources website- because we could create our own lesson plans incorporating differentiated instruction, there was more freedom than the other two projects. (Karen, Post-survey)

Challenges Faced by TCs: the Noted Progress

In the pre-survey, several themes emerged from TCs’ responses on perceived challenges that may hinder their DI implementation. Out of 17 TCs, eight mentioned time needed for preparation; seven mentioned challenges related to resources; seven mentioned admin-related reasons such as support, funding, class size, and PD; five mentioned student factors such as engagement and interest or special needs; four TCs stated teacher knowledge or skills; three mentioned online teaching during the pandemic; and one mentioned curriculum mandates.

In the post-survey, TCs reflected on the challenges they faced while trying to implement DI in their course assignments. Two main themes emerged as challenges from eight TCs’ responses: (1) specific content knowledge or skills related to an assignment (mentioned by five TCs) and (2) unknown students in the case of course assignments or having too many differences to account for in one classroom (mentioned by four TCs). With respect to the specific content knowledge and specific task skills, TCs said:

Some topics lend themselves better to EDI principles whereas others are heavily rooted in science and minute processes (e.g., metabolic processes). (Meredith, Post-survey)

It was very difficult to differentiate instruction within the DVG assignment, as it required a lot of external knowledge on how to do this effectively. (Roy, Post-survey)

It was difficult in the DVG because we wanted to keep the game simple and still incorporate DI and EDI. (Karen, Post-survey)

Four TCs mentioned the challenge related to having too many differences to account for or in their case creating a course assignment for a hypothetical classroom where students are unknown. TCs said:

The challenge is to cater to everyone’s individual needs. Yes, there are things we can do to differentiate learning that benefits all students, but there will always be some students left unaccounted for, no matter what. (Erin, Post-survey)

Difficult when you are not making it for a known group of students. You are unsure what to highlight and focus on for EDI. (Angela, Post-survey)

While the latter responses were written as a challenge, they actually represent a positive note. These statements reflect that TCs have shown appreciation and awareness of student differences, which is the core of DI principles. Finally, it is worth mentioning that in general the reported challenges are very specific in nature and are in contrast to those reported in the literature such as the lack of teachers’ knowledge or skills in DI, low teacher motivation, and lack of resources. The reported challenges are not profound so as to impact TCs’ implementation of DI.

Thus, when comparing TCs’ pre-course survey reflections about the expected challenges to those in the post-course survey, the previously emerging themes related to resource availability and TCs’ knowledge and skills implementing EDI strategies were not significant. The stated challenges at the end of the course revealed that resources and strategies provided in the course helped TCs surpass the perceived obstacle of preparing resources that reflect DI principles. This benefit is possibly due to the fact that TCs had gained practical experience creating such resources and advancing their pedagogical knowledge integrating DI strategies, which reiterates the effectiveness of the course in enhancing TCs’ DI conceptions and self-efficacy toward DI.

Conclusion

This research focuses on intermediate-senior STEM TCs’ teacher preparation emphasizing their implementation of DI in teacher education courses. TCs reflected on their improved ability to integrate DI practices in their STEM curriculum and pedagogy course assignments. This result highlights the positive impact of the course on their professional knowledge related to DI, and hence adequate preparation of teachers to implement DI in their future practices.

While some research studies show that novice teachers express less willingness to implement DI due to various challenges (Garrett, 2017; Rollins, 2010; Wertheim & Leyser, 2002), the STEM course with DI-focused elements highlights the importance of PD opportunities aimed at enhancing TCs’ implementation of DI. The STEM curriculum and pedagogy course adopted an intensive and explicit reflective approach in teaching about several elements, as well as DI through rounds of discussion, feedback on TCs’ course work, and scaffolded course tasks to ensure advancement in TCs’ understanding and skill mastery. The adopted strategies were rooted in socio-cultural learning theories and based on communities of practice through resource and expertise sharing. These results call for adopting similar training approaches in other courses in teacher education programs to ensure that DI principles and strategies are deeply understood and proficiently practiced by TCs. This finding is in accordance with research highlighting the importance of DI-focused training in teacher education programs on TCs’ understanding (Dack, 2018; Goodnough, 2010) and implementation of DI (Adlam, 2007; Wan, 2017).

Teacher candidates' coursework showed that they were able to design lesson plans and curriculum resources that are differentiated in content, process, and product, with higher proficiency in differentiating the process specifically. These results are reflected in the literature indicating that the content and product differentiation are less understood by teachers compared to the process (Rollins, 2010; Turner & Solis, 2017). It is important to note that the three assignments were helpful in different ways, which is also a scaffolding approach used by the TCs. TCs were trying different DI approaches in each assignment and choosing what was of particular relevance. For instance, the case studies enabled TCs to take diversity and different perspectives into consideration. DVGs are were of specific significance in differentiating the difficulty levels, scaffolding, and considering diversity and inclusion in race, gender, etc. On the other hand, the websites enabled TCs to apply all their acquired knowledge and skills about DI to create teaching and assessment resources. Both the wide variety and required depth of DI implementation in various course tasks ensured an adequate exposure of TCs to various forms of DI.

Finally, challenges encountered and anticipated by TCs are worth noting. When comparing TCs’ pre-course survey reflections about the expected challenges to those in the post-course survey, the previously identified themes related to resource availability and TCs’ knowledge and skills in implementing EDI strategies were not significant. In contrast to those reported in the literature such as the lack of teachers’ knowledge or skills in DI (Adlam, 2007), low teacher motivation (Garrett, 2017; Rollins, 2010; Wertheim & Leyser, 2002), and lack of resources (de Jager, 2017; Park & Datnow, 2017; Turner & Solis, 2017; Wan, 2017), the reported challenges do not reflect deep or profound obstacles that would impact TCs’ implementation of DI in the future. The stated challenges at the end of the course revealed that resources and strategies provided by the course helped TCs surpass the perceived obstacle of preparing resources that reflect DI principles.

Limitations

This study provides rich description of TCs’ DI implementation in the course from several data sources, thus ensuring data triangulation. Yet, the major limitation pertains to TCs’ implementation of DI in their practicum and future practices. Future research can further explore this aspect by observing TCs in their practicum to provide them with feedback and attain a more comprehensive understanding of their practices and DI implementation. Moreover, one of the major challenges encountered in this study was the COVID-19 pandemic which led to the 12-week course being offered online. This shift required all course activities to be conducted online, which may have affected TCs in terms of face-to-face collaborations and social engagement as they researched and developed assignments. Additionally, in general, the pandemic added a huge burden on TCs and can thus be perceived as a stressor that may have affected the quality of work that TCs produced. Finally, the unique nature of the STEM curriculum and pedagogy course, offered to specific TCs who are enrolled in the STEM specialty, may affect the extent to which one can generalize from the findings presented in this study.

Implications

This research addresses the most pressing challenges that hinder DI implementation as reported by teachers, such as availability of resources (Adlam, 2007; Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021; Paone, 2017), required time for lesson planning (Adlam, 2007; Brevik et al., 2018; Paone, 2017), and ability to plan for DI (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021; Kendrick-Weikle, 2015; Rollins, 2010). Thus, the course has addressed an important need for training TCs to enhance their understanding and implementation of DI (Casey & Gable, 2012; Rollins, 2010). One major challenge that warrants further research is training in-service teachers and TCs on differentiating instruction in online environments, given online teaching is gaining traction post-COVID-19 pandemic.

This research informs teacher educators and curriculum designers about practical measures to include DI practices in teacher education courses. This implication is timely as most teacher education programs are currently striving to integrate equitable and inclusive pedagogies in their curriculum and overall planning. The study shows that EDI practices such as DI must and can be woven into all requirements of teacher education programs, rather than restricting those principles to inclusive education or special education courses only. The study also informs heads of departments, policy makers, and school administrators about the successes and challenges of similar PD initiatives, in the hopes that more of these PD programs are implemented with in-service teachers to revitalize their teaching practices.

Data Availability

Raw data is available for transparency purposes.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This research has acquired ethical approval from Western University Non-Medical Research Ethics Board (Project ID: 114831).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abd-El-Khalick, F., & Lederman, N. G. (2000). The influence of history of science courses on students’ views of nature of science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37(10), 1057–1095. 10.1002/1098-2736(200012)37:10<1057::AID-TEA3>3.0.CO;2-C

- Adlam, E. (2007). Differentiated instruction in the elementary school: Investigating the knowledge elementary teachers posses when implementing differentiated instruction in their classrooms [PhD Thesis]. University of Windsor.

- Beasley, J. G., & Beck, D. E. (2017). Defining differentiation in cyber schools: What online teachers say. TechTrends, 61(6), 550–559. 10.1007/s11528-017-0189-x [Google Scholar]

- Birnie, B. F. (2017). A teacher’s guide to successful classroom management and differentiated instruction. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, B. R. (2018). Rigor and differentiation in the classroom: Tools and strategies (1st ed.). Routledge. 10.4324/9781351185912

- Brantley-Dias, L., Puvirajah, A., & Dias, M. (2021). Supporting teacher candidates’ multidimensional reflection: A model and a protocol. Reflective Practice, 22(2), 187–202. 10.1080/14623943.2020.1865904 [Google Scholar]

- Brevik, L. M., Gunnulfsen, A. E., & Renzulli, J. S. (2018). Student teachers’ practice and experience with differentiated instruction for students with higher learning potential. Teaching and Teacher Education, 71, 34–45. 10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.003 [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C. (2021). Educational equity in Canada: The case of Ontario’s strategies and actions to advance excellence and equity for students. School Leadership & Management, 41(4–5), 409–428. 10.1080/13632434.2019.1709165 [Google Scholar]

- Casey, M. K., & Gable, R. K. (2012). Perceived efficacy of beginning teachers to differentiate instruction. 44th Annual Meeting of the New England Educational Research Association. http://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/teacher_ed/7

- Chamberlin, M., & Powers, R. (2010). The promise of differentiated instruction for enhancing the mathematical understandings of college students. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications, 29(3), 113–139. 10.1093/teamat/hrq006 [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, P. (2007). Quantitative data analysis in education: A critical introduction using SPSS. Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Dack, H. (2018). Structuring teacher candidate learning about differentiated instruction through coursework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69, 62–74. 10.1016/j.tate.2017.09.017 [Google Scholar]

- Dack, H. (2019). The role of teacher preparation program coherence in supporting candidate appropriation of the pedagogical tools of differentiated instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 78, 125–140. 10.1016/j.tate.2018.11.011 [Google Scholar]

- de Jager, T. (2017). Perspectives of teachers on differentiated teaching in multi-cultural South African secondary schools. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 53, 115–121. 10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.08.004 [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus, O. N. (2012). Differentiated instruction: Can differentiated instruction provide success for all learners? National Teacher Education Journal, 5(3).

- DeCoito, I. (in press). STEMifying teacher education – A Canadian context. In A. M. Al-Balushi, L. Martin-Hansen, & Y. Song (Eds.), Reforming science teacher education programs in the STEM era: International practices. Springer.

- DeCoito, I., & Briona, L. K. (2020). Navigating theory and practice: Digital video games (DVGs) in STEM education. In V. L. Akerson & G. A. Buck (Eds.), Critical Questions in STEM Education (pp. 85–104). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- DeCoito, I., & Estaiteyeh, M. (2022, May). Addressing STEM teachers’ challenges in online teaching by enhancing their TPACK and creating digital resources. Canadian Society for the Study of Education (CSSE) Conference, Virtual.

- DeCoito, I., & Fazio, X. (2017). Developing case studies in teacher education: Spotlighting socio-scientific issues. Innovations in Science Teacher Education, 2(1).

- D’Intino, J. S., & Wang, L. (2021). Differentiated instruction: A review of teacher education practices for Canadian pre-service elementary school teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 1–14. 10.1080/02607476.2021.1951603

- DiPirro, J. (2017). Implementation of differentiated instruction: An analysis [PhD Thesis]. Rivier University.

- Dixon, F. A., Yssel, N., McConnell, J. M., & Hardin, T. (2014). Differentiated instruction, professional development, and teacher efficacy. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 37(2), 111–127. 10.1177/0162353214529042 [Google Scholar]

- EduGains. (2010). Student success: Differentiated instruction educator’s package. http://www.edugains.ca/resourcesDI/EducatorsPackages/DIEducatorsPackage2010/2010EducatorsGuide.pdf

- Egbo, B. (2012). What should preservice teachers know about race and diversity? Exploring a critical knowledge-base for teaching in 21st century Canadian classrooms. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education, 6(2). 10.20355/C5C30R

- Estaiteyeh, M., & DeCoito, I. (2023). Differentiated instruction in digital video games: STEM teacher candidates using technology to meet learners’ needs. Interactive Learning Environments. 10.1080/10494820.2023.2190360

- Farrell, T. S. C. (2015). Promoting teacher reflection in second-language education: A framework for TESOL professionals. Routledge.

- Gall, J. P., Gall, M. D., & Borg, W. R. (2005). Applying educational research: A practical guide (5th ed.). Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

- Garrett, S. (2017). A comparative study between teachers’ self-efficacy of differentiated instruction and frequency differentiated instruction is implemented [PhD Thesis]. Northcentral University.

- Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

- George, P. S. (2005). A rationale for differentiating instruction in the regular classroom. Theory into Practice, 44(3), 185–193. 10.1207/s15430421tip4403_2 [Google Scholar]

- Goodnough, K. (2010). Investigating pre-service science teachers’ developing professional knowledge through the lens of differentiated instruction. Research in Science Education, 40(2), 239–265. 10.1007/s11165-009-9120-6 [Google Scholar]

- Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K., & Vantieghem, W. (2021). Exploring pre-service teachers’ beliefs and practices about two inclusive frameworks: Universal design for learning and differentiated instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 107, 103503. 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103503

- Guay, F., Roy, A., & Valois, P. (2017). Teacher structure as a predictor of students’ perceived competence and autonomous motivation: The moderating role of differentiated instruction. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(2), 224–240. 10.1111/bjep.12146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubball, H., Collins, J., & Pratt, D. (2005). Enhancing reflective teaching practices: Implications for faculty development programs. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 35(3), 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kamarulzaman, M. H., Azman, H., & Zahidi, A. M. (2018). Research trend in the practice of differentiated instruction. The Journal of Social Sciences Research, 4(12), 648–668. [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick-Weikle, K. (2015). Illinois high school teachers’ understanding and use of differentiated instruction. Western Illinois University.

- Kizas, A. (2016). Differentiated instruction and student engagement: Effective strategies for teaching combined-grade classes at the secondary level. Canadian Music Educator, 57(2), 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. 10.2307/1163320 [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: A.k.a. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74–84. 10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751

- Levy, H. M. (2008). Meeting the needs of all students through differentiated instruction: Helping every child reach and exceed standards. The Clearing House, 81(4), 161–164. 10.3200/TCHS.81.4.161-164 [Google Scholar]

- Madkins, T. C., & Morton, K. (2021). Disrupting anti-blackness with young learners in STEM: Strategies for elementary science and mathematics teacher education. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 21(2), 239–256. 10.1007/s42330-021-00159-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeng, J. (2017). Using technology to facilitate differentiated high school science instruction. Research in Science Education, 47(5), 1075–1099. 10.1007/s11165-016-9546-6 [Google Scholar]

- Malloy, J. (2019). Gaps are not closing. We need to make a bold move. School Administrator, 76(1), 40–42.

- Manavathu, M., & Zhou, G. (2012). The impact of differentiated instructional materials on English language learner (ELL) students’ comprehension of science laboratory tasks. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 12(4), 334–349. 10.1080/14926156.2012.732255 [Google Scholar]

- Massouti, A. (2019). Inclusion and policy enactment in teacher education: A focus on pre-service teacher preparation for the inclusive classroom [PhD Thesis]. The University of Western Ontario.

- Massouti, A. (2021). Pre-service teachers’ perspectives on their preparation for inclusive teaching: Implications for organizational change in teacher education. Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 12(1), n1. [Google Scholar]

- McGhie-Richmond, D., Underwood, K., & Jordan, A. (2007). Developing effective instructional strategies for teaching in inclusive classrooms. Exceptionality Education Canada, 17(1), 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, L., & Hobson, B. (2005). One size does not fit all: Differentiation in the elementary grades. Beaverton School District Summer Institute, Beaverton, OR.

- Moldoveanu, M., Grenier, N., & Marca-Vadan, L. (2016). Professional profile of primary teachers in disadvantaged and Indigenous communities who use differentiated practices. 7302–7302. 10.21125/edulearn.2016.0593

- Mujawamariya, D., Hujaleh, F., & Lima-Kerckhoff, A. (2014). A reexamination of Ontario’s science curriculum: Toward a more inclusive multicultural science education? Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 14(3), 269–283. 10.1080/14926156.2014.874618 [Google Scholar]

- Niccum-Johnson, M. A. (2018). An investigation of the consistency of use of differentiated instruction in upper elementary classrooms [PhD Thesis]. McKendree University.

- Nicolae, M. (2014). Teachers’ beliefs as the differentiated instruction starting point: Research basis. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 128, 426–431. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.182 [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Education. (2017). Ontario’s education equity action plan. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-1_0/edu-Ontario-Education-Equity-Action-Plan-en-2021-08-04.pdf

- Paone, N. A. (2017). Middle school teachers’ perceptions of differentiated instruction: A case study [PhD Thesis]. Northcentral University.

- Paré, M., & Prud’homme, L. (Eds.). (2014). La différenciation dans une perspective inclusive: Intégrer les connaissances issues de la recherche pour favoriser la progression des élèves dans un groupe hétérogène. Revue suisse de pédagogie spécialisée. https://edudoc.ch/record/113215?ln=de

- Park, V., & Datnow, A. (2017). Ability grouping and differentiated instruction in an era of data-driven decision making. American Journal of Education, 123(2), 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Pincince, D. L. (2016). Participation in professional development and its role in the implementation of differentiated instruction in the middle school. Northeastern University.

- Pollard, A., & Tann, S. (1997). Reflective teaching in the primary school: A handbook for the classroom. Cassell London.

- Prud’Homme, L. (2007). La différenciation pédagogique: Analyse du sens construit par des enseignantes et un chercheur-formateur dans un contexte de recherche-action-formation. Université du Québec à Montréal.

- Rezai-Rashti, G., Segeren, A., & Martino, W. (2015). Race and racial justice in Ontario education: Neoliberalism and strategies of racial invisibility. In Building democracy through education on diversity (pp. 141–158). Brill Sense.

- Rezai-Rashti, G., Segeren, A., & Martino, W. (2017). The new articulation of equity education in neoliberal times: The changing conception of social justice in Ontario. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 15(2), 160–174. 10.1080/14767724.2016.1169514 [Google Scholar]

- Rezai-Rashti, G., & Solomon, P. (2008). Teacher candidates’ racial identity formation and the possibilities of antiracism in teacher education. In Comparative and global pedagogies: Equity, access and democracy in education (Vol. 2, pp. 167–188). Springer.

- Robinson, Q. E. (2017). Perceptions and adoption of differentiated instruction by elementary teachers [PhD Thesis]. Capella University.

- Rollins, R. (2010). Assessing the understanding and use of differentiated instruction: A comparison of novice and experienced technology education teachers. North Carolina State University.

- Roy, A., Guay, F., & Valois, P. (2013). Teaching to address diverse learning needs: Development and validation of a differentiated instruction scale. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(11), 1186–1204. 10.1080/13603116.2012.743604 [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo, T., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2012). Teacher educators’ perceptions and use of differentiated instruction practices: An exploratory investigation. Action in Teacher Education, 34(4), 309–327. 10.1080/01626620.2012.717032 [Google Scholar]

- Specht, J., McGhie-Richmond, D., Loreman, T., Mirenda, P., Bennett, S., Gallagher, T., Young, G., Metsala, J., Aylward, L., Katz, J., Lyons, W., Thompson, S., & Cloutier, S. (2016). Teaching in inclusive classrooms: Efficacy and beliefs of Canadian preservice teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(1), 1–15. 10.1080/13603116.2015.1059501 [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R. (2020). Case studies. In Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 435–454). Sage.

- Statistics Canada. (2017). Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: Key results from the 2016 Census. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-eng.pdf?st=qmWvzclz

- Statistics Canada. (2022). Immigrants make up the largest share of the population in over 150 years and continue to shape who we are as Canadians. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026a-eng.htm

- Suprayogi, M. N., Valcke, M., & Godwin, R. (2017). Teachers and their implementation of differentiated instruction in the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 291–301. 10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.020 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S. L. (2018). Educating 21st century learners: A phenomenological study of middle school teachers’ understanding and use of differentiated instruction [PhD Thesis]. Northcentral University.

- Tobin, R. (2007). Differentiating in the language arts: Flexible options to support all students. Canadian Children, 32(2).

- Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (1st ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). ASCD.

- Tomlinson, C. A., Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Brimijoin, K., Conover, L. A., & Reynolds, T. (2003). Differentiating instruction in response to student readiness, interest, and learning profile in academically diverse classrooms: A review of literature. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 27(2–3), 119–145. 10.1177/016235320302700203 [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, C. A., & Imbeau, M. B. (2010). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom. ASCD.

- Turner, W. D., & Solis, O. J. (2017). The misnomers of differentiating instruction in large classes. Journal of Effective Teaching, 17(3), 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Valiandes, S., & Tarman, B. (2011). Differentiated teaching and constructive learning approach by the implementation of ICT in mixed ability classrooms. Ahi Evran University Journal of Education Faculty (KEFAD), 12, 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Frèrejean, J., Dolmans, D., van Merriënboer, J., & Visscher, A. J. (2019). Capturing the complexity of differentiated instruction. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(1), 51–67. 10.1080/09243453.2018.1539013 [Google Scholar]

- Wan, S. W.-Y. (2016). Differentiated instruction: Hong Kong prospective teachers’ teaching efficacy and beliefs. Teachers and Teaching, 22(2), 148–176. 10.1080/13540602.2015.1055435 [Google Scholar]

- Wan, S. W.-Y. (2017). Differentiated instruction: Are Hong Kong in-service teachers ready? Teachers and Teaching, 23(3), 284–311. 10.1080/13540602.2016.1204289 [Google Scholar]

- Watts-Taffe, S., (Barbara) Laster, B. P., Broach, L., Marinak, B., McDonald Connor, C., & Walker-Dalhouse, D. (2012). Differentiated instruction: Making informed teacher decisions. The Reading Teacher, 66(4), 303–314. 10.1002/TRTR.01126 [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim, C., & Leyser, Y. (2002). Efficacy beliefs, background variables, and differentiated instruction of Israeli prospective teachers. The Journal of Educational Research, 96(1), 54–63. 10.1080/00220670209598791 [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, J., Gooderham, S., Duquette, C., Orders, S., & Cousins, J. B. (2019). Implementing differentiated instruction: A mixed-methods exploration of teacher beliefs and practices. Teachers and Teaching, 25(8), 1043–1061. 10.1080/13540602.2019.1699782 [Google Scholar]

- Willis, S., & Mann, L. (2000). Differentiating instruction: Finding manageable ways to meet individual needs. Curriculum Update, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data is available for transparency purposes.