Abstract

Increasing numbers of travellers returning from Cuba with dengue virus infection were reported to the GeoSentinel Network from June to September 2022, reflecting an ongoing local outbreak. This report demonstrates the importance of travellers as sentinels of arboviral outbreaks and highlights the need for early identification of travel-related dengue.

Background

In summer 2022, GeoSentinel Surveillance Network sites noticed an increase in patients with dengue virus (DENV) who had recently travelled to Cuba. In July 2022, the Cuban Ministry of Health issued an alert describing the largest outbreak of dengue reported in Cuba in the last 15 years, with evidence of the co-circulation of four DENV serotypes.1,2

We describe travellers from Cuba with travel-related DENV infection diagnosed from 1 January to 20 September 2022 seen at GeoSentinel sites.

Methods

GeoSentinel is a collaboration between the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Society of Travel Medicine that comprises 71 clinical sites globally and monitors infectious diseases in international travellers and migrants.

We included cases of confirmed and probable travel-related complicated and uncomplicated dengue acquired in Cuba from 1 January to 20 September 2022 reported to GeoSentinel. Confirmed cases were defined as a compatible clinical illness and appropriate exposure history according to expert assessment (recent travel to Cuba) with either DENV isolation, a positive DENV nucleic acid test, positive NS-1 antigen detection or seroconversion with a 4-fold rise in IgG anti-dengue antibody titres. Probable cases were defined as a compatible clinical illness and appropriate exposure history with either a single positive dengue IgM or high positive dengue IgG. ‘Complicated’ dengue was defined as a case with evidence of clinically significant plasma leakage or bleeding, organ failure or shock (i.e. severe dengue per World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines), or patients with warning signs (i.e. dengue with warning signs per defined in WHO guidelines).3 Uncomplicated dengue was defined as a compatible clinical illness and no evidence of complications. Data were analysed using SAS v9.4 (Cary, North Carolina).

Results

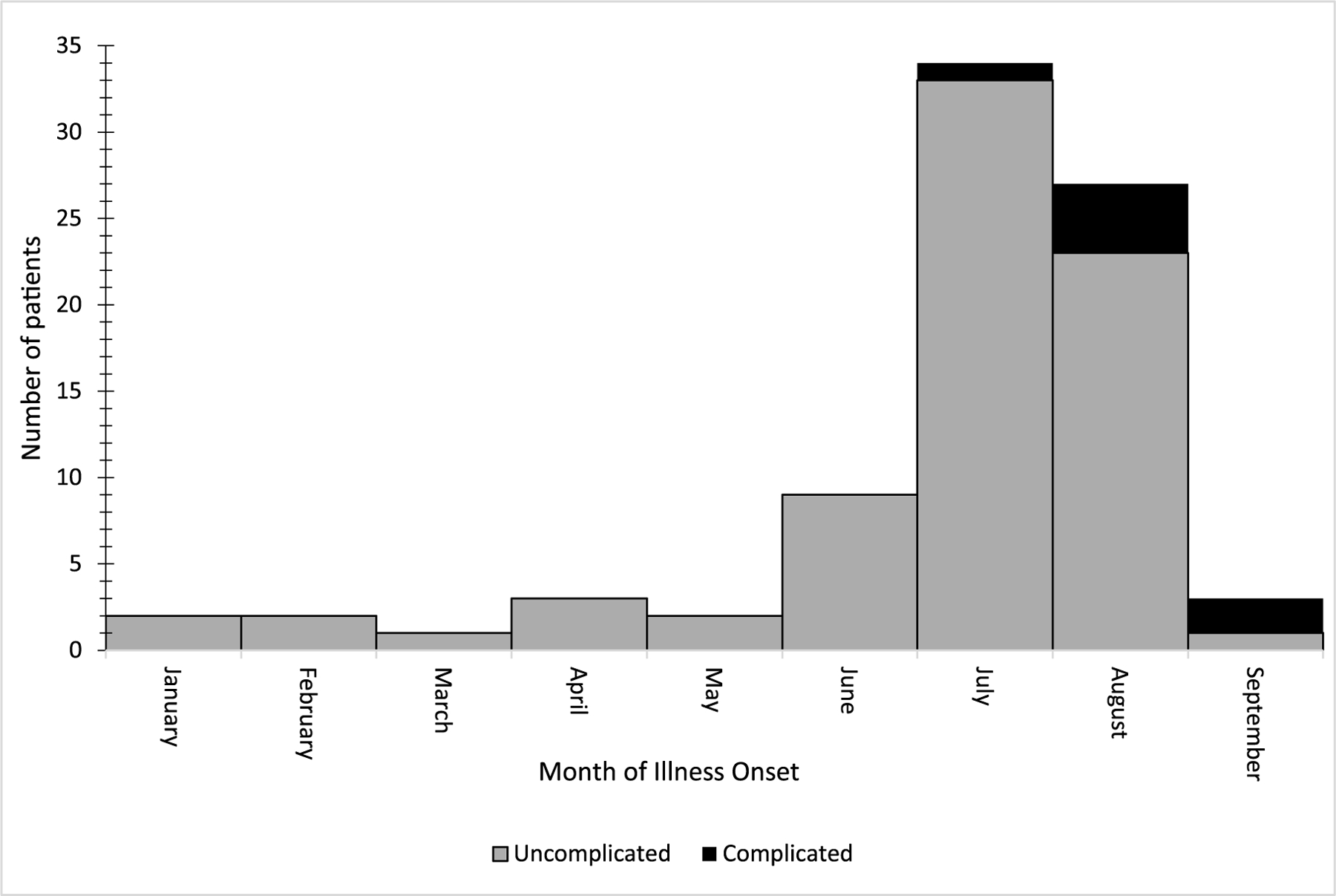

In total, 83 travellers from Cuba with DENV infection (73 confirmed and 10 probable) were identified (Figure 1); most infections occurred from June to August. The median age was 34 years (range: 13–65 years); 44.6% were female (Table 1). Patients were seen after returning from Cuba at 18 GeoSentinel sites in 10 countries (most frequently Spain; 61.5%). The median time between travel and presentation to a GeoSentinel site was 5 days (interquartile range: 3–7 days). Most patients travelled to Cuba for tourism (79.3%); 19.5% were born in Cuba and were visiting friends and relatives. Destinations visited in Cuba were available for 35 patients; 28 (80.0%) reported visiting Havana or Varadero as well as Cayo Coco, Cienfuegos, Holguín, Pinar del Río, Playa Giron, Playa Larga, Santa Clara, Santo Espiritu, Trinidad and Viñales. The median trip duration was 15 days (range: 5–226; interquartile range: 12–22). Of 74 patients with information available, only 23.0% reported a pre-travel consultation.

Figure 1.

Number of patients with uncomplicated and complicated dengue acquired in Cuba by month of illness onset, reported to GeoSentinel, 1 January–20 September 2022 (N = 83)

Table 1.

Patient and travel characteristics among patients with confirmed and probable dengue acquired in Cuba reported to GeoSentinel, 1 January–20 September 2022 (n = 83)

| Characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 34 (13–65) | ||

| Female sex | 37 | 44.6 | |

| GeoSentinel site countrya | Spain | 51 | 61.5 |

| Germany | 11 | 13.3 | |

| Canada | 5 | 6.0 | |

| France | 4 | 4.8 | |

| Italy | 3 | 3.6 | |

| Belgium | 2 | 2.4 | |

| The Netherlands | 2 | 2.4 | |

| Romania | 2 | 2.4 | |

| Sweden | 2 | 2.4 | |

| Switzerland | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Travel reasonb | Tourism (vacation) | 65 | 79.3 |

| Visiting friends and relatives | 16 | 19.5 | |

| Missionary/humanitarian/volunteer | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Median trip duration, days (range; IQR) | 15 (5–226; 12–22) | ||

| Had a pretravel consultationc | 17 | 23.0 |

IQR = interquartile range

All patients were residents of the GeoSentinel site country that diagnosed them, except for one patient who was a resident of The Bahamas seen in Germany.

Of 82 with information available.

Of 74 with information available.

The most frequently reported symptoms were fever, chills and sweats (82; 98.8%) (Table 2). Three patients (3.6%) were co-infected with DENV and SARS-CoV-2 including one who was admitted to the intensive care unit due to severe dengue. Seven patients (8.4%) had complicated dengue; of these, four had warning signs, one had severe dengue and two had missing details. Of the seven patients with complicated dengue, five had data available to classify the dengue episode as primary, based on absent IgG in serum samples during the acute phase. Twenty-four patients (28.9%) were hospitalized; one was admitted to the ICU. DENV serotypes were available for 11 patients; these included DENV-1 (3; 27.3%), DENV-3 (7; 63.6%) and DENV-4 (1; 9.1%). There were no deaths.

Table 2.

Clinical information for patients with confirmed and probable dengue acquired in Cuba reported to GeoSentinel, 1 January–20 September 2022 (N = 83)

| Clinical information | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 (confirmed) | 3 | 3.6 | |

| Severity of dengue | Uncomplicated | 76 | 91.6 |

| Complicated | 7 | 8.4 | |

| Symptomsa | Fever, sweats, chills | 82 | 98.8 |

| Headache | 48 | 57.8 | |

| Acute diarrhoea | 35 | 42.2 | |

| Exanthem | 34 | 41.0 | |

| Myalgia | 32 | 38.6 | |

| Nausea | 28 | 33.7 | |

| Fatigue | 26 | 313 | |

| Arthralgia | 23 | 27.7 | |

| Abdominal pain | 15 | 18.1 | |

| Vomiting | 13 | 15.7 | |

| Anorexia | 8 | 9.6 | |

| Non-exanthematous skin lesion | 8 | 9.6 | |

| Eye symptoms | 6 | 7.2 | |

| Dizziness | 4 | 4.8 | |

| Itching | 4 | 4.8 | |

| Cough | 3 | 3.6 | |

| Focal musculoskeletal pain | 3 | 3.6 | |

| Focal rash | 3 | 3.6 | |

| Arthritis | 2 | 2.4 | |

| Dysuria | 2 | 2.4 | |

| Sore throat | 2 | 2.4 | |

| Bloody diarrhoea | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Confusion | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Dysgeusia | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Urinary frequency | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Syncope | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Other, not specified | 6 | 7.2 | |

| Hospitalizedb | 24 | 28.9 |

The three patients with DENV and COVID-19 co-infection reported fever/sweats/chills (n = 3), myalgias (n = 3), arthralgias (n = 2), abdominal pain (n = 1), acute diarrhoea (n = 1), fatigue (n = 1), focal musculoskeletal pain (n = 1), headache (n = 1) and sore throat (n = 1).

Of 24, 1 (4.2%) was hospitalized in the intensive care unit.

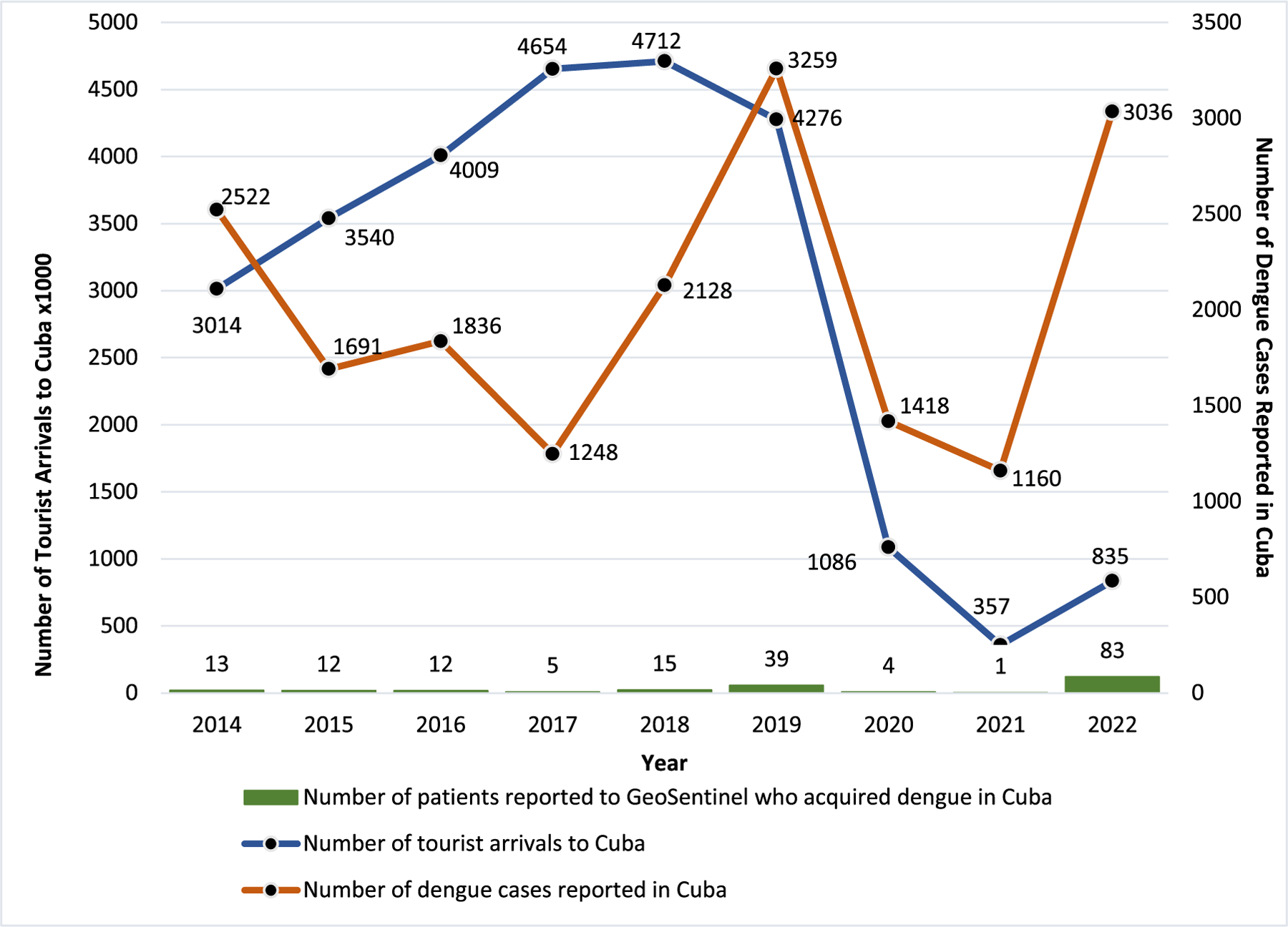

GeoSentinel sites recorded 188 patients with travel-related DENV infections from Cuba between 2014 and 2022 (Figure 2). When comparing the number of DENV cases in Cuba reported to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) to GeoSentinel patients with DENV infection by year, peaks occurred in 2019 and 2022.

Figure 2.

Number of confirmed and probable dengue cases acquired in Cuba reported to GeoSentinel* by year in the context of the annual number of tourist arrivals to Cuba$ and reported number of DENV cases in Cuba reported to PAHO§, 2014–2022. DENV = dengue virus, PAHO = Pan American Health Organization, *Reported through 20 September 2022, $Reported to the World Bank at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL?locations=CU and Trading Economics https://tradingeconomics.com/cuba/tourist-arrivalsthroughJuly2022, §Reported to PAHO through epidemiological week 26 (26 June–2 July), 2022

Discussion

From 1 January to 20 September 2022, GeoSentinel sites have reported the largest number of patients with DENV from returning travellers to Cuba since 2014. Cuba has been particularly affected with more cases in 2022 than in the past 8 years.4

Cuba has reported several major DENV outbreaks since 1977, especially in the eastern provinces and the capital, Havana.5 In the past 2 years, vector control measures have been negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, full-scale fumigation was restricted to homes where there was a person with a fever or who tested positive for DENV. However, fumigation alone is likely insufficient.6 With rainy season in Cuba running from May to October, it remains unclear whether number of travel-related DENV infections will continue to rise.7

The increase of imported dengue cases by travellers is occurring in a year that has not yet achieved the volumes of pre-pandemic tourism. Cuba’s Ministry of Tourism expects to reach 2.5 million visitors before the end of 2022,8 so early reporting to raise awareness about this ongoing outbreak in Cuba is imperative to prevent and detect potential infection amongst international travellers.

In recent years, some European countries with competent local vectors such as Ae. albopictus (Croatia, France, Italy and Spain) have identified autochthonous transmission of DENV from viraemic travellers.9 Therefore, early identification of cases through traveller surveillance with local vector monitoring, and rapid public health response is needed in areas at risk for local transmission.

Less than a quarter of patients received a pre-travel consultation before travelling to Cuba, a lost opportunity to receive the appropriate preventive measures information to protect against mosquito bites.

GeoSentinel sites specialize in travel and tropical medicine; therefore, these data may not be generalizable to all persons who acquire DENV in Cuba. Comparisons between the number of dengue cases acquired in Cuba reported to GeoSentinel, the number of tourist arrivals and the number of dengue cases in Cuba reported by PAHO were made using unequal time periods due to the availability of data at the time of this report.

This report highlights the importance of sentinel surveillance of returned travellers to identify cases and monitor for travel-related DENV infections. GeoSentinel surveillance data can help alert clinicians, public health officials and international travellers of outbreaks.

Funding

This project was funded through a Cooperative Agreement between the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Society of Travel Medicine (Federal Award Number: 1 U01CK000632-01-00).

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Florida Department of Health. Florida Arboviral Surveillance [cited 12 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/mosquito-borne-diseases/_documents/2022-week35-arbovirus-surveillance-report.pdf.

- 2.Ministerio de Salud Pública de la República de Cuba. Actualización sobre situación epidemiológica y programas priorizados [cited 30 August 2022]. Available from: https://salud.msp.gob.cu/ofrece-ministro-de-salud-publica-actualizacion-sobre-situacion-epidemiologica-y-programas-priorizados/.

- 3.World Health Organization. Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control: new edition [cited 31 August 2022]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44188. [PubMed]

- 4.Pan American Health Organization. PAHO/WHO Data—Reported Cases of Dengue Fever in the Americas [cited 30 August 2022]. Available from: https://www3.paho.org/data/index.php/en/mnu-topics/indicadores-dengue-en/dengue-nacional-en/252-dengue-pais-ano-en.html.

- 5.Revista Cubana de Medicina Tropical. Vigilancia de laboratorio de dengue y otros arbovirus en Cuba, 1970–2017 [cited 31 August 2022]. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0375-07602019000100008.

- 6.Cubanet. Dengue fever alert in Cuba: the largest number of out-breaks in the last fifteen years [cited 31 August 2022]. Available from: https://www.cubanet.org/english/dengue-fever-alert-in-cuba-the-largest-number-of-outbreaks-in-the-last-fifteen-years/.

- 7.Schwartz E, Weld LH, Wilder-Smith A et al. Seasonality, annual trends, and characteristics of dengue among ill returned travelers, 1997–2006. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14:1081–8. 10.3201/eid1407.071412 PMID: 18598629; PMCID: PMC2600332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agencia Cubana de Noticias. Cuba invita a empresarios mexicanos a ampliar vínculos económicos (+Fotos) [cited 1 September 2022]. Available from: http://www.acn.cu/economia/96882-cuba-invita-a-empresarios-mexicanos-a-ampliar-vinculos-economicos.

- 9.European Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autochthonous transmission of dengue virus in mainland EU/EEA, 2010-present [cited 30 July 2022]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topics-z/dengue/surveillance-and-disease-data/autochthonous-transmission-dengue-virus-eueea.