Abstract

Evidence suggests that a repertoire of Vibrio cholerae genes are differentially expressed in vivo, and regulation of virulence factors in vivo may follow a different pathway. Our work was aimed at characterization of in vivo-grown bacteria and identification of genes that are differentially expressed following infection by RNA arbitrarily primed (RAP)-PCR fingerprinting. The ligated rabbit ileal loop model was used. The motility of in vivo-grown bacteria increased by 350% over that of in vitro-grown bacteria. Also, the in vivo-grown cells were more resistant to killing by human serum. By using the RAP-PCR strategy, five differentially expressed transcripts were identified. Two in vitro-induced transcripts encoded polypeptides for the leucine tRNA synthatase and the 50S ribosomal protein, and the three in vivo-induced transcripts encoded the SucA and MurE proteins and a polypeptide of unknown function. MurE is a protein involved in the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway. The lytic profiles of in vivo- and in vitro-grown cells suspended in distilled water were compared; the former was found to be slightly less sensitive to lysis. Ultrathin sections of both cells observed under the transmission electron microscope revealed that in contrast to the usual wavy discontinuous membrane structure of the in vitro-grown cells, in vivo-grown cells had a more rigid, clearly visible double-layered structure. The V. cholerae murE gene was cloned and sequenced. The sequence contained an open reading frame of 1,488 nucleotides with its own ribosome-binding site. A plasmid containing the murE gene of V. cholerae was transformed into V. cholerae 569B, and a transformed strain, 569BME, containing the plasmid was obtained. Ultrathin sections of 569BME viewed under a transmission electron microscope revealed a slightly more rigid cell wall than that of wild-type 569B. When V. cholerae 569B and 569BME cells were injected separately into ligated rabbit ileal loops, the transformed cells had a preference for growth in the ileal loops versus laboratory conditions.

Cholera is still a major public health problem in developing countries as well as in some developed countries. The causative organism, Vibrio cholerae, is a gram-negative curved rod, and the life-threatening watery diarrhea is largely due to the action of the secreted cholera toxin on the epithelium of the small intestine (8). Several lines of evidence suggest that a number of V. cholerae genes are differentially expressed in vivo following infection. The major virulence genes of V. cholerae O1 biotype Classical under the coordinate regulation of the transcriptional activator ToxR are maximally expressed in vitro. In contrast, in the intestinal lumen, conditions repress the expression of ToxR-controlled virulence factors (16, 17). Thus, to induce the ToxR-controlled virulence genes in vivo, V. cholerae may recognize other unknown external signals in the host environment (20). V. cholerae cells are extremely sensitive to a wide variety of chemicals, particularly hydrophobic compounds and neutral and anionic detergents, and are much more permeable than Escherichia coli cells (21). This is primarily due to the presence of exposed phospholipids in the outer leaflet of the outer membrane and relatively less negative charge on the polysaccharide moiety of lipopolysaccharide (21). The murein network of V. cholerae is weak, and the cells lyse rapidly in hypotonic medium as well as in the presence of chelating agents such as Tris and EDTA (13). Unlike other gram-negative organisms which are resistant to penicillin, V. cholerae cells are equally sensitive to penicillin and ampicillin and are much more sensitive to most of the beta-lactam antibiotics than E. coli (25).

Recently, using a method based on tnpR operon fusions encoding a site-specific DNA recombinase, 13 transcriptional units of V. cholerae were identified that were induced during infection in an infant-mouse model of cholera. Five of these were predicted to encode polypeptides with diverse functions in metabolism, biosynthesis, and motility. One encoded a secreted lipase, two seemed to be antisense to genes involved in motility, and five were predicted to encode polypeptides of unknown function (3). Using signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) to conduct a screen for random insertion mutations that affect colonization in the suckling mouse model for cholera, five mutants with transposon insertions in toxin coregulated pilus (TCP) biogenesis genes were isolated. Insertions in lipopolysaccharide, biotin, and purine biosynthetic genes were also found to cause colonization defects. Similar results were observed for mutations in homologs of pta and ptfA, two genes involved in phosphate transfer. The screen also identified several novel genes, disruption of which also caused colonization defects in the mouse model (5). Although two different techniques were used, none of the in vivo-induced genes was identified twice. Also, it is well known that the genes in the tcp operon are responsible for colonization. Only one such gene was isolated, suggesting that only one third of all the genes responsible could be identified by the STM method. Moreover, with methods involving transposon mutagenesis, only genes that are induced in vivo are identified, but the genes that are repressed may hold some major information regarding the mechanism of pathogenesis of the organism.

The RNA arbitrarily primed PCR (RAP-PCR) method amplifies subsets of an mRNA population and separates the resulting cDNAs by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). These two steps resulted in a collection of DNA molecules that were flanked at their 3′ and 5′ ends by the exact sequence (and complement) of the arbitrary primer. These in turn formed templates for high-stringency PCR amplification. Although the intensities of different bands within the same fingerprint vary, the intensity of a band between fingerprints appears to be proportional to the concentration of its corresponding template or mRNA (28). A complete pattern of all mRNAs expressed in a particular cell is possible with a reasonable number of primer pairs (27). This technique was used to examine differential gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in response to peroxide treatment (29). Two identical stress-inducible genes were found in different parts of the genome. Several differential-display reverse transcriptase-PCR fragments from Legionella pneumophila induced after a 4-h incubation of macrophage-like cells were identified (9).

In this study, we attempted a characterization of in vivo-grown bacteria and identification of genes that are differentially expressed following infection by RAP-PCR fingerprinting. We identified a set of genes that are differentially expressed in vivo, one of which is involved in the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway. We cloned this gene and investigated the potential role of the gene product in the survival of V. cholerae in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The V. cholerae and E. coli strains were maintained at −70°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing 20% (vol/vol) glycerol. E. coli cells were grown in LB medium or M9 medium, and V. cholerae cells were grown in NB or LB medium. Ampicillin was used at 100 μg/ml for E. coli and 50 μg/ml for V. cholerae where appropriate. Plasmids were incorporated into V. cholerae cells by transformation by the method of Panda et al. (18). All cloning experiments were done in pBluescriptKS+. The plasmids were maintained and amplified in E. coli strains DH5α and XL1 Blue.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Vibrio cholerae | ||

| 569B | Prototroph, highly toxinogenic, biotype Classical, serotype Inaba | 17a |

| 569BME | 569B containing pAMT150 | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| K-12 | Wild type | Laboratory collection |

| XL1 Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔ15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| DH5α | F− f80d/lacZΔ M15ΔlacZYA argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rk− mk−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| CSR603 | thr-1 ara-14 leuB6Δ (gpt-proA)62 lacY1 tsx-33 suppE44 phr-1 galK2 λ− rac recA1 gyrA98 rpsL31 kdgK51 xyl-5 mtl-1 uvrA6 | Aziz Shankar |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript KS | 2.96 kb, Ampr | Stratagene |

| pRAP1 | pBluescript carrying 145-bp V. cholerae murE cDNA fragment | This study |

| pRAP2 | pBluescript carrying 331-bp V. cholerae leucyl-tRNA synthase cDNA fragment | This study |

| pRAP3 | pBluescript carrying 145-bp V. cholerae cDNA fragment | This study |

| pRAP4 | pBluescript carrying 248-bp V. cholerae 50S ribosomal protein cDNA fragment | This study |

| pRAP5 | pBluescript carrying 175-bp V. cholerae sucA gene cDNA fragment | This study |

| pAMT200 | pBluescript carrying 2-kb KpnI-SacI fragment of V. cholerae genomic DNA | This study |

| pAMT150 | pBluescript carrying 1.5-kb PCR fragment of V. cholerae genomic DNA | This study |

DNA preparation and manipulation.

Genomic DNA from V. cholerae 569B was prepared from proteinase K-digested and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide-precipitated cell lysates by standard procedures (2). Plasmid DNA was prepared by the alkaline lysis method (14). Restriction enzymes and DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs Inc. (Beverly, Mass.) and used according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For Southern blotting, restriction enzyme-digested chromosomal or plasmid DNA was electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels and blotted on nylon membranes (Nytran; Schleicher & Schuell), using 10× SSC (1× SSC is 0.015 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) (14). The blots were hybridized with DNA fragments labeled with [32P]dCTP (Amersham International, Amersham, U.K.) prepared by using a random-primed labeling kit (New England Biolabs). Subgenomic libraries of V. cholerae DNA were constructed in plasmid pBluescript. Genomic DNA was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, and the fragments within the size range of interest were excised from agarose gels, purified, ligated with linearized and dephosphorylated plasmid pBluescript, and transformed into E. coli according to standard recombinant DNA techniques (14).

Ligated rabbit ileal loop model.

In vivo growth of V. cholerae strains was carried out in the rabbit ileal loop model essentially as described by De and Chatterjee (6). Briefly, rabbits fasted for 48 h were anesthetized, and the small intestine was tied into consecutive 6-cm and 2-cm segments proximally to the mesoappendix. An inoculum of 0.5 μl of V. cholerae strains containing about 5 × 106 CFU was introduced into each 6-cm segment, while one loop was inoculated with saline as a negative control. The intestine was returned to the peritoneal cavity, and the incision was closed. After 16 to 18 h, the animals were sacrificed, and the small intestine was removed. Fluid accumulated in each loop was separately collected and measured. The V. cholerae count in the fluid was measured by plating on thiosulfate-citrate-bile salt-sucrose (TCBS) agar plates. Although no fluid accumulated in the loops inoculated with saline, these loops were also washed and scraped, and bacterial cells in the washings were counted to determine whether the intestine contained any inhabitant. At least two loops in the same animal were inoculated with each bacterial strain, and each strain was tested in at least five individual animals.

Isolation of in vivo-grown bacteria.

V. cholerae strains was grown in rabbit ileal loops. After 16 to 18 h, the animals were sacrificed and the small intestine was removed. Fluid accumulated in each loop was collected separately. The fluid was then spun at 1,000 rpm for 5 min to remove the debris. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 10 min to pellet the bacteria.

Swarm plate assay.

V. cholerae cells were stabbed into semisolid agar plates containing LB (pH 7.2) solidified with 0.3% Bactoagar (Difco). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 16 to 18 h, and swarm diameters were measured.

Serum assays.

Blood was collected from five healthy individuals who gave informed consent and was then allowed to clot. Serum was collected, pooled, and stored at −70°C in aliquots. With normal human serum and serum heat treated by incubation at 56°C for 30 min to inactivate complement components, serum assays were performed by a previously described procedure with slight modification (26). Two different assays were carried out. In one, the concentration of serum was kept at 35% and 2 × 109 bacterial cells from an exponential-phase or overnight culture or rabbit intestine were added. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Counts of viable cells were done by taking samples at 0, 1, 2, and 3 h. Percentages for each time point were obtained from surviving viable-cell count versus the initial viable-cell count. For each culture condition, assays were performed at least four different times in 35% serum and 35% heat-inactivated serum. In the other assay, 5 × 109 bacterial cells isolated and diluted from an exponential-phase or overnight culture or rabbit intestine were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with serum and inactivated serum at concentrations of 20, 40, 60, and 80%. Dilutions of samples were plated onto NA plates and incubated overnight at 37°C, and counts were determined. Percentages for each serum concentration were obtained from surviving viable-cell count versus the initial viable-cell count. For each culture condition, assays were performed at least two different times.

RNA isolation and analysis.

For isolation of RNA, cells were grown to the late logarithmic phase in LB (pH 7.2) or overnight in the rabbit intestine. Total RNA was extracted and purified by using guanidium isothiocyanate as described elsewhere (2). RNA samples (15 to 25 μg/well) were electrophoresed in duplicate in 1% agarose–2.1 M formaldehyde–morpholinepropanesulfonic acid gels, and one part was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized with UV light to confirm equal loading of all samples. The other part of the gel was blotted onto nylon membranes by using 20× SSC and hybridized with labeled probes as described elsewhere (2).

DNA sequencing.

Nucleotide sequence was determined with double-stranded plasmid DNA as the template either by the dideoxy chain termination method (24) or by cycle sequencing with the Applied Biosystem Prism dye system (Perkin-Elmer). For manual sequencing, [α-35S]dATP and the Sequenase 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (US Biochemical Corp.) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RAP-PCR fingerprinting of RNA.

RAP was performed essentially as described by Welsh et al. (28). RNA was first treated with RNase-free DNase I (Life Technologies). The reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 M EDTA, and the RNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform (1:1), ethanol precipitated, washed, and dried. To 10 μl of sample containing 200 ng of this DNase-treated RNA dissolved in water, arbitrarily chosen primer was added to a final concentration of 1 μM, and the mixture was incubated at 68°C for 10 min and then chilled on ice. cDNA synthesis buffer (10 μl) containing 5 U of Superscript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 100 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 20 mM dithiothreitol, and 2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates was added. First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out at 37°C for 1 h. After cDNA synthesis, 10 μl of buffer containing 2 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 5 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 μM same arbitrarily chosen primer, 100 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol), and 0.5 U of Taq polymerase was added to the 20-μl cDNA sample. The thermal cycling parameters were as follows: one low-stringency cycle; 94°C (5 min), 40°C (5 min), 72°C (5 min); then 30 high-stringency cycles at 94°C (1 min), 60°C (1 min), and 72°C (2 min). A 10-μl amount of 80% formamide with bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol dyes was added to 5 μl of each PCR sample. The samples were heated to 75°C for 15 min and loaded on a standard 5% polyacrylamide–50% urea sequencing gel prepared in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA and electrophoresed at 300 V until the xylene cyanol dye reached the bottom of the gel. The gel was dried under vacuum onto 3MM paper (Whatman). The RAP fingerprint was visualized by autoradiography using Kodak X-Omat AR film. The primers used in this study were RSP, AACAGCTATGACCATG; MSP, GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT; BGA1, GTCATCCGTCGATTGCCGGA; BGC2, GACCATTGCATAACGCTGAC; BGT3, CCTTAGTGCGTATTATGT; ARB1, CCATGCGCATGCATGAGA; ARB2, AGAGAGAAACCCACCAGA; and ARB3, CCGCACGCGCACGCAAGG.

Lysis of whole cells.

Cells from an exponential-phase or overnight culture or rabbit intestine were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 10 min) and suspended in distilled water. The extent of lysis was estimated by monitoring the decrease in A585 with respect to the initial value at time zero.

Assay of stability of pAMT150 in 569BME.

V. cholerae 569BME was grown overnight in the laboratory and in rabbit ileal loops. The bacteria were harvested, diluted, and plated onto NA and NA plates with ampicillin. Counts of viable cells were made from these plates.

Electron microscopy.

For whole cells, cells were fixed with 6% gluteraldehyde (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), washed in phosphate-buffered saline, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined under a JEOL transmission electron microscope at 60 kV. For thin-section electron microscopy, cells were fixed first with 6% gluteraldehyde in 0.125 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 14 to 16 h and then with 1% osmium tetroxide (Ted Pella, Inc., Tustin, Calif.) in Kellenberger buffer for 16 to 20 h at room temperature. The fixed cells were washed for 2 h in 0.5% uranyl acetate in the above buffer, dehydrated with ascending concentrations of ethanol, and embedded in spur medium (Poly Sciences, Inc., Warrington, Pa.) at 70°C for 48 h as described previously (13). Sections were cut with a Du Pont diamond knife on an LKB Nova ultramicrotome and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. To visualize the peptidoglycan, a special staining procedure as described elsewhere (11) was used. The sections were floated on 1% periodic acid for 15 min, rinsed with distilled water, and treated with phosphotungstic acid in 10% chromic acid and rinsed for 10 min in distilled water. These were then examined under a JEOL transmission electron microscope at 60 kV.

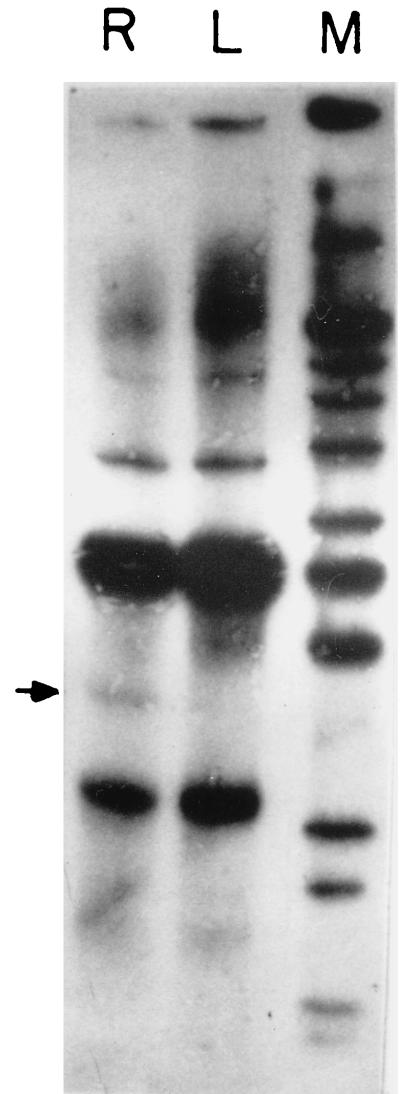

Protein labeling in maxicells.

Plasmid-coded proteins were examined using the maxicell technique (23). Strain CSR603 carrying either pBluescript or pAMT150 was grown (2 × 108 CFU/ml) in M9 medium containing 1% casamino acids. The cell pellet was suspended in the dilution buffer and irradiated with UV light (50 J/m2). The irradiated cells were suspended in fresh medium and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. At the end of this period, 200 μg of d-cycloserine per ml was added, and the incubation was continued for 16 h at 37°C with constant shaking at slow speed. The cells were harvested, washed and suspended in fresh sulfur-depleted medium, and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The plasmid-coded proteins were then labeled with [35S]methionine (5 μCi/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were harvested and washed with M9 medium, and the cell lysate was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–15% PAGE followed by fluorography and autoradiography of the dried gel.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the V. cholerae murE gene appear in the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ databases under accession no. AF141867. The nucleotide sequences of RAP products appear under accession nos. AF211980, AF211981, AF211982, AF211983, and AF217393.

RESULTS

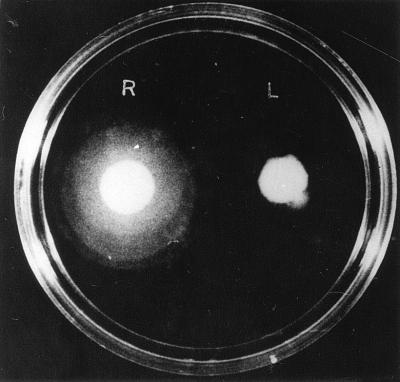

Comparison of swarming ability of in vivo- and in vitro-grown V. cholerae on motility agar plates.

It has recently been reported that expression of the major virulence factors and motility are oppositely regulated in V. cholerae (7). Inside the host, the motility of the bacteria is important for their movement from the point of ingestion to a niche in the small intestine, where they colonize. The swarming ability of the in vivo-grown cells in semisolid motility medium containing 0.3% agar in LB medium (pH 7.2) was compared with that of V. cholerae cells in the exponential phase grown under laboratory conditions. Under these conditions, the in vitro-grown 569B cells displayed little motility in the swarm plates. However, the in vivo-grown cells were significantly more motile, and a 350% increase in swarm diameter was observed (Fig. 1). This suggests that regulation of the major virulence factors in vivo and motility may follow an alternative or slightly modified pathway.

FIG. 1.

Swarming behavior of V. cholerae cells grown in vitro (L) and in vivo (R) on motility agar plates.

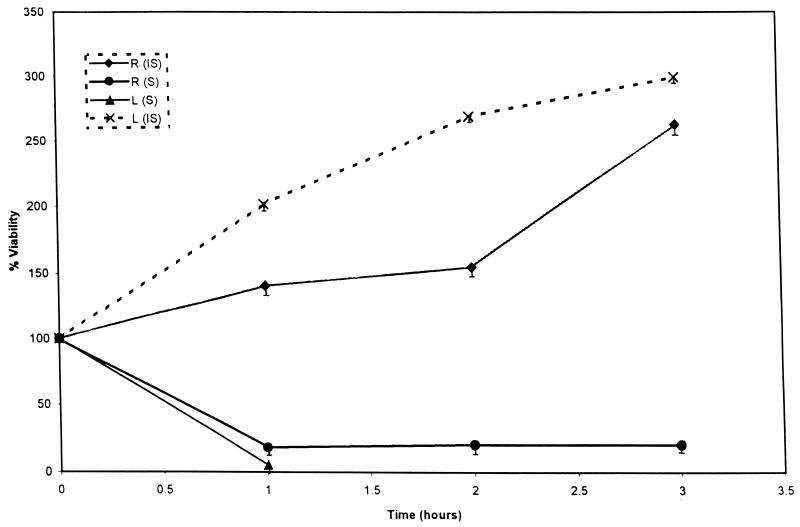

Serum sensitivity of in vivo- and in vitro-grown V. cholerae.

Once inside the host, the bacteria have to evade the host immune system and then colonize the intestine. It has been reported that mutations in the toxR and tcp genes rendered V. cholerae more sensitive to the vibriocidal activity of antibody and complement (19). It is in this context that the serum sensitivity of in vivo- and in vitro-grown V. cholerae were compared.

Serum samples collected from five healthy individuals were pooled to eliminate interindividual variation. Serum assays were performed with normal human serum and heat-inactivated serum. Two different assays were performed. In one, the concentration of serum was kept at 35% and 2 × 109 bacterial cells isolated and diluted from an exponential-phase or overnight culture or rabbit intestine were added. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Viable-cell counts were determined in duplicate at the end of each hour for 3 h.

The results are shown in Fig. 2 as percent viability. As expected for inactivated serum in all three cultures, bacteria increased in number by 150 to 200% in the first hour, with growth reaching a plateau by the third hour of incubation. In presence of normal serum, the in vivo-grown bacteria showed 80% killing in the first hour, reached a plateau, and actually had a slight increase in number after the second hour. In contrast, the laboratory-grown cultures showed more than 90% killing in the first hour and mostly did not survive till the second hour of incubation.

FIG. 2.

Serum assays of behavior of V. cholerae cells grown in vitro (L) and in vivo (R) in 35% serum (S) or 35% heat-inactivated serum (IS) with an inoculum of 2 × 109 cells. Samples were taken in duplicate at the start and each hour for 3 h. Results are shown as percent viability.

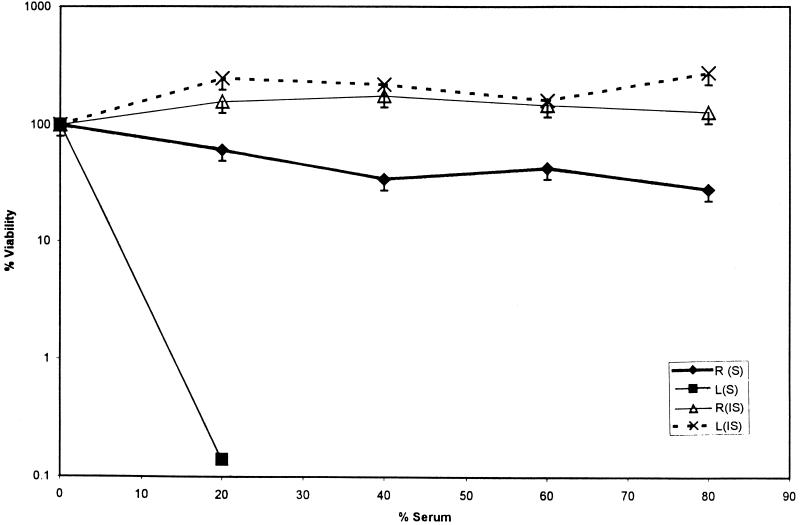

In the other assay, 5 × 109 bacterial cells isolated and diluted from an exponential-phase or overnight culture or rabbit intestine were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with both serum and inactivated serum concentrations of 20, 40, 60, and 80%. Viable-cell counts were determined in duplicate at the end of 2 h. Figure 3 shows the results as percent viability. It was found that the in vitro-grown cells did not survive for more than 2 h at serum concentrations higher than 20%, whereas in vivo-grown bacteria showed about 25 to 40% survival after 2 h of incubation.

FIG. 3.

Serum assays of behavior of V. cholerae cells grown in vitro (L) and in vivo (R) in 20, 40, 60, and 80% serum (S) or heat inactivated-serum (IS) with an inoculum of 2 × 109 cells. Samples were taken in duplicate at the start and after 2 h of incubation. Results are shown as percent viability.

RAP-PCR fingerprinting of RNA.

Bacteria grown under the appropriate condition were immediately frozen on an ice-salt mixture to minimize degradation of mRNA, and total RNA was isolated as described in Materials and Methods. Total RNA isolated from bacteria grown in the laboratory to the exponential phase and bacteria from ligated rabbit ileal loops were subjected to RAP fingerprinting. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase with an arbitrarily selected primer. The arbitrarily primed first-strand cDNA is heat denatured and subjected to arbitrarily primed second-strand synthesis using Taq polymerase at low stringency. Products that have the primer sequence at both ends are then PCR amplified at high stringency with simultaneous radiolabeling. Products were separated by denaturing PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The resulting fingerprint patterns were highly reproducible.

Each fingerprint yielded a pattern of 18 or more clearly visible PCR products (Fig. 4). Pooled RNA samples from at least four different animals were used for each experiment to eliminate rabbit-to-rabbit variations. Fingerprints were generated using eight different primers. For each primer there were 18 or more observable bands in each lane, but only a few differentially amplified cDNA products were observed. The RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase prior to fingerprinting. This eliminated the possibility of genomic DNA contamination. Controls without reverse transcriptase were used with every reaction to rule out possible contamination. Bands specific to in vivo and in vitro RNA were identified, and differentially amplified RAP products were eluted as described in Materials and Methods. At least two separate reactions were performed for each primer for each RNA sample. Only bands that appeared to be differentially expressed in both the reactions were used for further analysis. These were then cloned into the SmaI site of the pBluescript vector, and a partial nucleotide sequence was obtained.

FIG. 4.

RAP-PCR fingerprinting of V. cholerae grown in vivo (R) and in vitro (L). The arrow shows a differentially expressed band. Lane M, HaeIII-digested φX174 DNA as markers.

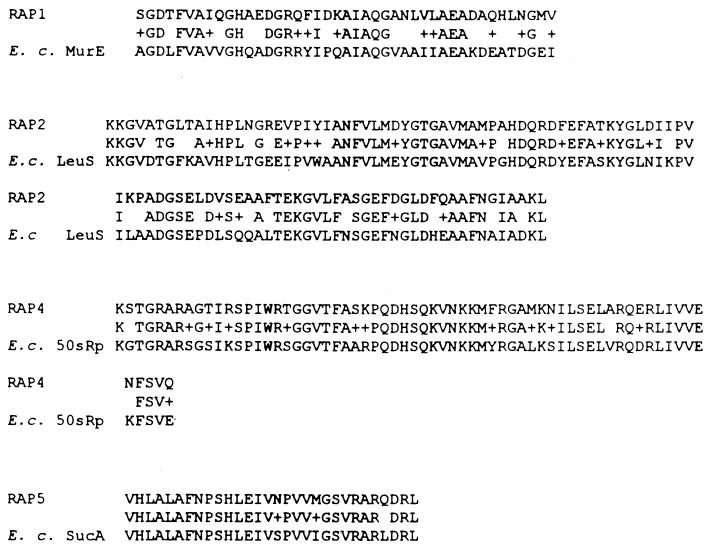

Five differentially expressed transcripts were sequenced, and the database was searched for homology using the BLASTN and BLASTX (1) programs (Table 2). None of the transcripts showed any homology at the nucleotide level except pRAP5. It is induced in vivo and showed homology to the z62r gene of V. cholerae in the database. The z62r gene is a hypothetical open reading frame (ORF) from V. cholerae. At the protein level it showed homology to the E. coli SucA protein (Fig. 5). Interestingly iviII, an in vivo-induced transcript in V. cholerae reported by Camilli and Mekalanos (3), is also a part of the V. cholerae sucA gene. SucA is part of a multisubunit enzyme that catalyzes a step in the tricarboxylic acid cycle in which α-ketogluterate is oxidatively decarboxylated to succinyl coenzyme A and carbon dioxide. pRAP1 induced in vivo was also predicted to encode a polypeptide that had high similarity to the MurE protein of E. coli, which catalyzes an intermediate step in the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 5). pRAP2 induced in vitro was predicted to be part of a gene encoding a polypeptide highly homologous to the leucine tRNA synthetase (LeuS) gene of E. coli (Fig. 5). It catalyzes the binding of l-leucine to the leucyl-tRNA in the presence of ATP. pRAP4 induced in vitro was also found to be a part of a gene encoding a polypeptide with a very high similarity to the 50S ribosomal protein of E. coli (Fig. 5). pRAP3 did not show significant homology to any sequence deposited in the database.

TABLE 2.

List of isolated RAP products

| Clone | Homology | Induction |

|---|---|---|

| pRAP1 | MurE protein of E. coli | In vivo |

| pRAP2 | Leucyl-tRNA synthase protein of E. coli | In vitro |

| pRAP3 | None found | In vivo |

| pRAP4 | 50S ribosomal protein of E. coli | In vitro |

| pRAP5 | z62r gene of V. cholerae and SucA protein of E. coli | In vivo |

FIG. 5.

Selected results of BLAST search of sequences of the RAP products. E.C., E. coli; 50sRp, 50S ribosomal protein. +, conserved substitution.

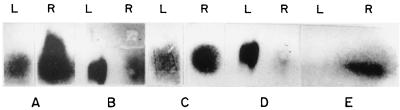

Northern blot analysis.

To examine the level of expression of the differentially expressed transcripts, RNA isolated from in vivo- and in vitro-grown bacteria was Northern blotted and probed with the five cDNA fragments isolated by RAP-PCR (Fig. 6). In some cases RNA dot blots were also used. Specific signals could be detected in each case. Clones pRAP1, pRAP3, and pRAP5 showed induction in vivo; pRAP2 and pRAP4 were induced in vitro. The blots were then stripped and reprobed with a V. cholerae rRNA probe as a control (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Northern and dot blot analyses of the isolated RAP products pRAP1 (A), pRAP2 (B), pRAP3 (C), pRAP4 (D), and pRAP5 (E). L and R, in vitro and in vivo RNA, respectively.

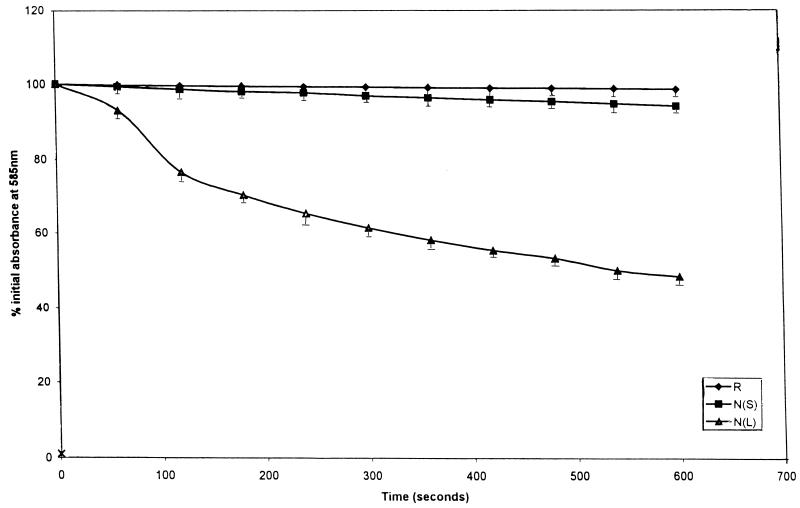

Lysis of V. cholerae cells grown in vivo.

The structure of the murein network plays a significant role in determining the stability of cell surfaces of bacteria. Several studies have indicated the delicate nature of the murein networks of V. cholerae cells (4, 13, 25). It is a real mystery how these cells survive in the human intestine. Our finding that a peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway gene is induced in vivo led us to investigate whether in vivo-grown cells are equally susceptible to lysis.

Cells isolated from rabbit ileal loops and cells grown in the laboratory in the stationary or logarithmic phase of growth were suspended in distilled water, and the extent of lysis was compared (Fig. 7). For cells in the stationary phase of growth, the extent of lysis was less than that for cells in the logarithmic phase of growth. In vivo-grown cells were found to be slightly less sensitive to lysis upon suspension in distilled water than those grown in vitro.

FIG. 7.

Lytic profile of V. cholerae cells suspended in distilled water. R and N, cells grown in vivo and in vitro, respectively; L and S, logarithmic and stationary phase of growth, respectively.

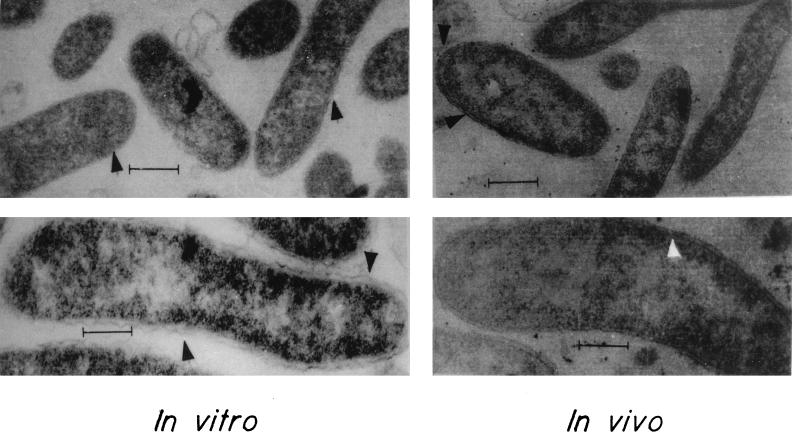

Ultrastructure of in vivo-grown cells.

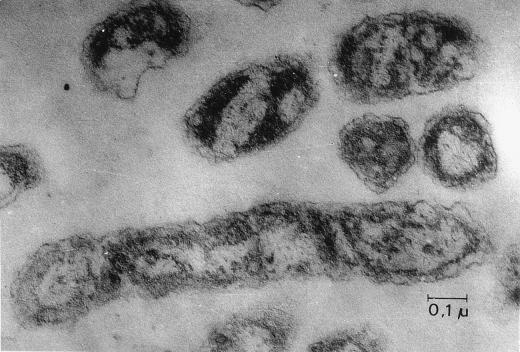

The murein network of a bacterial cell is mainly responsible for its shape and rigidity. On finding that the murE gene is induced in vivo, we examined ultrathin sections of V. cholerae cells grown in vivo and in vitro under the transmission electron microscope. A special periodate staining procedure for peptidoglycan was used (11). The laboratory-grown cells had a barely visible discontinuous membrane structure, whereas in in vivo-grown cells, a typical rigid railroad pattern was observed (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Ultrathin sections of in vivo- and in vitro-grown V. cholerae cells. Magnificaiton for upper panels, ×25,000; magnification for lower panels, ×80,000. Arrowheads, outer membrane and peptidogly can layer.

The above observations indicated that V. cholerae cells modulate their peptidoglycan level in vivo, which helps them to survive in conditions within the host. This is a very new finding, and to determine if the induced expression of murE is solely responsible for these phenomena, we decided to clone and sequence the murE gene of V. cholerae.

murE gene of V. cholerae: cloning, nucleotide sequence, and protein sequence.

The V. cholerae murE gene was cloned by screening a subgenomic library using the 150-bp cDNA fragment obtained from RAP-PCR fingerprinting as the probe. The sequence of the 2-kb insert in plasmid pAMT200 contained an ORF of 1,488 nucleotides, which is capable of coding for a protein of 495 amino acids whose predicted amino acid sequence is about 56% identical to that of the E. coli MurE protein. A putative ribosome-binding site (GAGA) was centered about 10 nucleotides upstream of the translation initiation site. The synthetase activity of the MurE protein requires ATP hydrolysis, and as previously observed in E. coli (15), a domain characteristic of ATP-binding proteins was found between amino acids 121 and 125. Analysis of the sequence upstream and downstream of murE revealed that the pbpB gene lies immediately upstream and the murF gene lies immediately downstream. This organization is similar to that in E. coli. As our aim was to check the effect of expression of murE in V. cholerae, we amplified a 1,540-bp fragment from the 2-kb region. This contained the putative ORF for murE and nucleotides up to 50 bp upstream of the start codon and thus minimized the possibility of the presence of promoter elements and partial codons of genes downstream of the murE ORF. The PCR product was ligated into the SmaI site of pBluescript and designated pAMT150, and the sequence was verified by cycle sequencing.

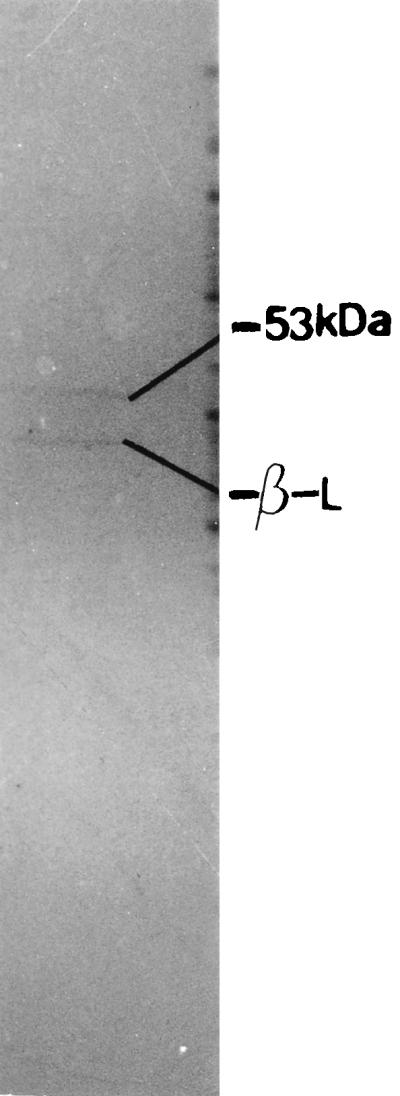

The protein(s) encoded by this fragment was examined by using maxicell analysis (23). Plasmid pAMT150 carrying the 1.5-kb DNA fragment was transformed into E. coli strain CSR603. Cells of E. coli CSR603 carrying pAMT150 were irradiated with UV light, labeled with [35S]methionine for 1 h, and the extract of soluble proteins was assayed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as described in Materials and Methods. The 1.5-kb DNA fragment was found to encode a protein of 53 kDa (Fig. 9), which is in agreement with the predicted amino acid sequence of 495 amino acids. Plasmid pAMT150 containing the murE gene of V. cholerae was transformed into V. cholerae 569B, and a transformant strain designated 569BME was obtained. 569BME grew well in the presence of ampicillin but tended to lose the plasmid in the absence of the antibiotic. To check if any change in the murein network of this strain has occurred, the lytic profile of 569BME in distilled water was studied as described above. No change in the lytic profile was observed compared with that of the wild-type 569B.

FIG. 9.

Maxicell analysis of the proteins encoded by plasmid pAMT150. Two bands, one for the β-lactamase (β-L) and another corresponding to a 53-kDa protein, were observed.

Ultrathin sections of 569BME were stained and observed under a transmission electron microscope. Though the cell wall seemed to be slightly more rigid than that of wild-type 569B, the difference was not very clear (Fig. 10).

FIG. 10.

Ultrathin section of V. cholerae 569BME observed under a transmission electron microscope. Bar, 0.1 μm.

V. cholerae 569B and 569BME cells (about 107 CFU) were injected separately into ligated rabbit ileal loops, and after 16 to 18 h the animal was sacrificed and the intestinal fluid was collected. No difference in the amount of fluid accumulated in loops containing 569B and 569BME was observed. The collected fluid was diluted and plated onto NA and NA-ampicillin plates. On comparing the counts of 569BME plated onto NA and NA-ampicillin plates, it was found that 569BME cultured in rabbit ileal loops lost pAMT150 about four times less often than when cultured overnight in the laboratory in absence of antibiotic. This shows that the transformed cells prefer the ileal loops over laboratory conditions for growth.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that identification of V. cholerae genes that are differentially expressed following infection can be successfully achieved by RAP-PCR fingerprinting. The ligated rabbit ileal loop model was chosen because it provides a close mimicry of the human gut condition. Moreover, it allows comparison of the pathogenicity of more than one strain in the same animal. Lastly, compared to mice models, a greater quantity of bacteria could be isolated from each experiment. The bacteria isolated from the accumulated fluid showed little or no contamination, proving the hypothesis that once given the chance to colonize, V. cholerae outgrows all other intestinal flora.

The swarming ability of the in vivo-grown cells in semisolid motility medium was measured. In vivo-grown bacteria were found to have a swarm diameter 350% larger than that of in vitro-grown bacteria. The swarm plate assay used in this study represents both motility and chemotaxis; a more detailed study would involve measuring the speed using state-of-the-art video microscopy. The in vivo-grown cells were also more resistant to killing by human serum. This is direct evidence that V. cholerae cells adapt for survival in the intestinal milieu. It had been postulated that expression of the major virulence factors and motility are oppositely regulated in V. cholerae (7). It has also been reported that mutations in the toxR and tcp genes rendered V. cholerae more sensitive to the vibriocidal activity of antibody and complement (19). Therefore, our observation that an increase in both motility and resistance to serum sensitivity of in vivo-grown bacteria leads us to the hypothesis that expression of the major virulence genes may follow an alternative or a slightly modified pathway in vivo. A more detailed study involving mutations in candidate genes should be undertaken to identify the genes responsible for these phenotypes.

A recent paper by Camilli and colleagues (12) provides direct evidence that in the infant mouse model, ToxR-regulated genes like ctx and tcp are expressed in vivo with a somewhat different kinetic pattern. We did not get any ToxR- or Tcp-regulated genes because the technique we used actually amplifies and differentiates between mRNA under two or more different conditions. ToxR- and Tcp-regulated genes have a considerable level of expression both in vitro and in vivo. We chose bands that have a considerable and reproducible difference in expression levels in vivo and in vitro, so this may also be the reason that we missed the induced expression of these genes. Also, the results obtained from RAP-PCR analysis are always limited by the total number of primers or primer combinations used.

One of the transcripts found to be induced in vitro was predicted to encode a polypeptide highly homologous to the leucine tRNA synthetase (LeuS) gene of E. coli. The LeuS protein ligates the leucine amino acid to the leucyl-tRNA in presence of ATP. Thus, by regulation of this enzyme in vitro, the regulation of synthesis of a wide variety of proteins requiring this particular aminoacyl tRNA can be achieved. The other in vitro-induced transcript was found to be a part of a gene encoding a polypeptide with a very high similarity to the 50S ribosomal protein of E. coli. The 50S ribosomal protein is required for protein synthesis. In fact, we identified two genes that are repressed in vivo, and both relate to protein synthesis. This is not surprising, as in the stressful environment within the host, very few proteins are allowed to be synthesized at a high rate. This helps the pathogen make proper use of the limited resources in vivo and synthesize proteins that are essential for virulence and survival within the host.

Of the three in vivo-induced cDNA fragments, one corresponded to the already identified iviII gene of V. cholerae. Interestingly, iviII is actually an in vivo-induced transcript in V. cholerae, as reported by Camilli and Mekalanos (3). At the protein level, it showed homology to the E. coli SucA protein. SucA is part of a multisubunit enzyme that catalyzes a step in the tricarboxylic acid cycle in which α-ketogluterate is oxidatively decarboxylated to succinyl coenzyme A and carbon dioxide. The fact that a particular in vivo-induced gene was identified by two different techniques is an indirect proof of the reliability and accuracy of both methods. The second in vivo-induced transcript was predicted to encode a polypeptide that had high similarity to the MurE protein of E. coli, which catalyzes an intermediate step in the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway. The third cDNA fragment did not show homology to any sequence in the database.

The fact that murE, a gene involved in the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway, is induced in vivo did not come as a surprise to us. In fact, several studies have indicated the fragile nature of the murein networks of V. cholerae cells (4, 13, 25). In E. coli, the peptidoglycan network is thin but “more than a monolayer” (10). The peptidoglycan content of V. cholerae 569B is about 0.5% of the cellular dry weight, a percentage much lower than that in other gram-negative bacteria (13). It is really intriguing how these cells survive in the human intestine. When the lytic profiles of in vivo- and in vitro-grown cells suspended in distilled water were compared, the former was found to be slightly less sensitive to lysis. Ultrathin sections of both cells observed under the transmission electron microscope revealed that in contrast to the usual wavy discontinuous membrane structure of the in vitro-grown cells, in vivo-grown cells had a more rigid, clearly visible double-layered structure. These experiments were repeated several times, each time with a different animal, and were reproducible. Moreover, the periodate method of staining (11) reflects peptidoglycan only. The increased level of peptidoglycan could be due to differences in osmolarity, especially since it has been reported earlier that the level of peptidoglycan in V. cholerae grown in 1% NaCl is higher than when grown without NaCl (13). The murein network of a cell is responsible for its shape and rigidity, protecting the cell against osmotic shock. This observation indicates that V. cholerae cells modulate their peptidoglycan content in vivo to help them survive in the intestinal environment.

Using the murE cDNA fragment as probe, the V. cholerae murE gene was cloned and the cloned gene was confirmed by comparison of its nucleotide sequence with the database. The sequence contained an ORF of 1,488 nucleotides with its own ribosome-binding site. The analysis of sequences upstream and downstream of the murE gene revealed that the organization of the locus in V. cholerae is similar to that in E. coli, with the pbpB gene immediately upstream and the murF gene immediately downstream of the predicted ORF. Maxicell analysis revealed a 53-kDa protein, in agreement with the predicted amino acid sequence of 495 amino acids.

The obvious question arose of whether the change in cell surface characteristics of V. cholerae in vivo is due to the induction of murE alone or a multigenic process. A plasmid containing the murE gene of V. cholerae was transformed into V. cholerae 569B, and transformed strain 569BME containing the plasmid was obtained. The lytic profile of V. cholerae 569BME suspended in distilled water did not show any significant difference compared with the wild-type strain. Ultrastructural analysis revealed a slightly more rigid and continuous membrane structure than in the wild-type 569B. This indicates that although a slightly greater rigidity in the cell surface may have been imparted by expression of the cloned murE gene, to achieve the major changes in phenotypes observed in in vivo-grown cells, a multigene process is involved. To find a more complete answer to the question, the other genes related to the cell surface and peptidoglycan structure of V. cholerae need to be identified and analyzed.

Recent reports showed that the intracellular residence of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium within epithelial cells is accompanied by significant changes in the bacterial cell wall (22). It has also been reported that environmental non-O1 vibrios are more resistant to various lytic agents than their O1 counterparts and also that they possess more peptidoglycan (4). Our findings suggest that pathogenic strains of V. cholerae may in fact modulate their peptidoglycan content in response to environmental stimuli, as within the host. However, not all the phenotypic differences observed persist after subculture. Using promoter reporter constructs, the factors that stimulate the induction of these can be identified, and the data obtained may lead to the discovery of new therapeutic and prophylactic agents against this pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grant SP/SO/D-56/96 from the Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India. A.C. is grateful to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research for a research fellowship.

We thank S. N. Dey, I. Guhathakurta, and R. Banerjee for excellent technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F, Brent M R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camilli A, Mekalanos J J. Use of recombinase gene fusions to identify Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:671–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhuri K, Bhadra R K, Das J. Cell surface characteristics of environmental and clinical isolates of Vibrio cholerae non-O1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3567–3573. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.11.3567-3573.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang S L, Mekalanos J J. Use of signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis to identify Vibrio cholerae genes critical for colonization. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:797–805. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De S N, Chatterjee S N. An experimental study of the mechanisms of action of Vibrio cholerae on the intestinal mucus membrane. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1953;46:559–562. doi: 10.1002/path.1700660228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardel C, Mekalanos J J. Alterations in Vibrio cholerae motility phenotypes correlate with changes in virulence factor expression. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2246–2255. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2246-2255.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaper J B, Morris J G, Jr, Levine M N. Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:48–86. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwaik Y A, Pederson L L. The use of differential display-PCR to isolate and characterize a Legionella pneumophila locus induced during the intracellular infection of macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:543–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labischinski H, Goodell E W, Goodell A, Hochberg M L. Direct proof of a “more than single layered” peptidoglycan architechtiure of Escherichia coli W7: a neutron small-angle-scattering study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:751–756. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.751-756.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leduc M, Frehel C, van Heijenoort J. Correlation between degradation and ultrastructure of peptidoglycan during autolysis of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:627–635. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.627-635.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S M, Hava D L, Waldor M K, Camilli A. Regulation and temporal expression patterns of Vibrio cholerae virulence genes during infection. Cell. 1999;99:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohia A, Majumdar S, Chatterjee A N, Das J. Effect of changes in the osmolarity of the growth medium of Vibrio cholerae cells. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:1158–1166. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.1158-1166.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaud C, Parquet C, Flouret B, Blanot D, Heijenoort J. Revised interpretation of the sequence containing the murE gene encoding UDP-N-acetylmuramyl-tripeptide synthetase of Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1990;269:277–280. doi: 10.1042/bj2690277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. Synthesis of cholera toxin is positively regulated at the transcriptional level by toxR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3471–3475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Mukherjee S. Principles and practice of typing V. cholerae. Methods Microbiol. 1978;12:483–497. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panda D K, Dasgupta U, Das J. Transformation of Vibrio cholerae by plasmid DNA. Gene. 1991;105:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90520-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsot C, Taxman E, Mekalanos J J. ToxR regulates the production of lipoproteins and expression of serum resistance in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1641–1645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsot C, Mekalanos J J. Expression of ToxR, the transcriptional activator of virulence factors of Vibrio cholerae, is modulated by the heat shock response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9898–9902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul S, Chaudhuri K, Chatterjee A N, Das J. Presence of exposed phospholipids in the outer membrane of Vibrio cholerae. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:755–761. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-4-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quintela J C, de Pedro M A, Zollner P, Allmaier G, Garcia-del-Portillo F. Peptidoglycan structure of Salmonella typhimurium growing within cultured mammalian cells. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:693–704. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2561621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sancar A, Hach A A, Rupp W D. Simple method for identification of plasmid-coded proteins. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:692–693. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.1.692-693.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulsen A R. DNA sequencing with chain termination inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sengupta T K, Chaudhuri K, Majumdar S, Lohia A, Chatterjee A N, Das J. Interaction of Vibrio cholerae cells with β-lactam antibiotics: emergence of resistant cells at a high frequency. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:788–795. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.4.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor P W. Measurement of the bactericidal activity of the serum. In: Sussman M, editor. The virulence of Escherichia coli. London, England: Academic Press Ltd.; 1985. pp. 445–457. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Lory S, Ramphal R, Jin S. Isolation and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes inducible by respiratory mucus derived from cystic fibrosis patients. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:1005–1012. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welsh J, McClelland M. Fingerprinting genomes using PCR with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;21:4272–4280. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong K K, McClelland M. Stress-inducible gene of Salmonella typhimurium identified by arbitrarily primed PCR of RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:639–643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]