Abstract

Background

Delusional disorder is commonly considered to be difficult to treat. Antipsychotic medications are frequently used and there is growing interest in a potential role for psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in the treatment of delusional disorder.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of medication (antipsychotic medication, antidepressants, mood stabilisers) and psychotherapy, in comparison with placebo in delusional disorder.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register (28 February 2012).

Selection criteria

Relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating treatments in delusional disorder.

Data collection and analysis

All review authors extracted data independently for the one eligible trial. For dichotomous data we calculated risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) on an intention‐to‐treat basis with a fixed‐effect model. Where possible, we calculated illustrative comparative risks for primary outcomes. For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD), again with a fixed‐effect model. We assessed the risk of bias of the included study and used the GRADE approach to rate the quality of the evidence.

Main results

Only one randomised trial met our inclusion criteria, despite our initial search yielding 141 citations. This was a small study, with 17 people completing a trial comparing CBT to an attention placebo (supportive psychotherapy) for people with delusional disorder. Most participants were already taking medication and this was continued during the trial. We were not able to include any randomised trials on medications of any type due to poor data reporting, which left us with no usable data for these trials. For the included study, usable data were limited, risk of bias varied and the numbers involved were small, making interpretation of data difficult. In particular there were no data on outcomes such as global state and behaviour, nor any information on possible adverse effects.

A positive effect for CBT was found for social self esteem using the Social Self‐Esteem Inventory (1 RCT, n = 17, MD 30.5, CI 7.51 to 53.49, very low quality evidence), however this is only a measure of self worth in social situations and may thus not be well correlated to social function. More people left the study early if they were in the supportive psychotherapy group with 6/12 leaving early compared to 1/6 from the CBT group, but the difference was not significant (1 RCT, n = 17, RR 0.17, CI 0.02 to 1.18, moderate quality evidence). For mental state outcomes the results were skewed making interpretation difficult, especially given the small sample.

Authors' conclusions

Despite international recognition of this disorder in psychiatric classification systems such as ICD‐10 and DSM‐5, there is a paucity of high quality randomised trials on delusional disorder. There is currently insufficient evidence to make evidence‐based recommendations for treatments of any type for people with delusional disorder. The limited evidence that we found is not generalisable to the population of people with delusional disorder. Until further evidence is found, it seems reasonable to offer treatments which have efficacy in other psychotic disorders. Further research is needed in this area and could be enhanced in two ways: firstly, by conducting randomised trials specifically for people with delusional disorder and, secondly, by high quality reporting of results for people with delusional disorder who are often recruited into larger studies for people with a variety of psychoses.

Plain language summary

Treatments for delusional disorder

Delusional disorder is a mental illness in which long‐standing delusions (strange beliefs) are the only or dominant symptom. There are several types of delusions. Some can make the person affected feel that they are being persecuted or can cause anxiety that they have an illness or disease that they do not have. People can have delusions of grandeur, so that they feel like they occupy a high position or are famous. Delusions can also involve jealousy of others or involve strange beliefs about body image, such as that they have a particular bodily defect.

Delusional disorder is considered difficult to treat. Antipsychotic drugs, antidepressants and mood‐stabilising medications are frequently used to treat this mental illness and there is growing interest in psychological therapies such as psychotherapy and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as a means of treatment.

This review aimed to assess the effectiveness of all current treatments for people with delusional disorder. A search for randomised controlled trials was run in 2012. Authors found 141 citations in the search but only one trial, randomising 17 people, could be included in the review. The study compared the effectiveness of CBT with supportive psychotherapy for people with delusional disorder. Participants were already taking medication and this was continued during the trial. The review was not able to include any studies or trials involving medications of any type used to treat delusional disorder.

For the study that was included, there was limited information presented that we could use. Firm conclusions were difficult to make and no evidence on improving people's behaviour and overall mental health was available. More people left the study early from the supportive psychotherapy group, but number of participants was small and the overall difference between the groups was not enough to conclude one treatment was better than the other. A positive effect for CBT was found for people's social self esteem, although again, this finding is limited by the low quantity and quality of the data and does not relate to people's social or everyday functioning.

Currently there is an overall lack of high quality evidence‐based information about the treatment of delusional disorders and insufficient evidence to make recommendations for treatments of any type. Until such evidence is found, the treatment of delusional disorders will most likely include those that are considered effective for other psychotic disorders and mental health problems.

Further large‐scale and high quality research is needed in this area. Research could be improved by conducting trials specifically for people with delusional disorder.

Ben Gray, Senior Peer Researcher, McPin Foundation: http://mcpin.org/.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Adjunct cognitive behavioural therapy versus adjunct supportive psychotherapy.

| Adjunct cognitive behavioural therapy compared to adjunct supportive psychotherapy (both with standard medication for most patients) for delusional disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with delusional disorder Settings: community Intervention: cognitive behavioural therapy Comparison: attention (both with standard medication) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Attention (mainly with standard medication) | Cognitive behavioural therapy(mainly with standard medication) | |||||

| Global state: Clinically significant improvement | See comment | No study reported this outcome | ||||

| Mental state: Delusions ‐ clinically significant improvement | See comment | MADS reported in the single relevant small study, but not a clinical scale and no report of symptomatic improvement on delusions | ||||

| Mental state: Depression BDI Follow‐up: 6 months | CBT ‐ average score 12.0 (SD 14.4, N = 11) Attention 'placebo' ‐ average score 18.3 (SD 7.8, N = 6) |

Not estimable | 17 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | Data skewed | |

|

Mental state:

Anxiety BAI Follow‐up: 6 months |

CBT ‐ average score 16.1 (SD 14.6, N = 11) Attention 'placebo' ‐ average score 14.0 (SD 14.2, N = 6) |

Not estimable | 17 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | Data skewed | |

| Service use: Admission | See comment | No study reported this outcome | ||||

| Social function: Self worth ‐ average score Social Self‐Esteem Inventory Follow‐up: 6 months | The mean social functioning: self worth average score in the intervention groups was 30.5 higher (7.51 to 53.49 higher) | 17 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |||

| Adverse event: Leaving the study early Follow‐up: 6 months | Low | RR 0.17 (0.02 to 1.18) | 24 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | ||

| 100 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (2 to 118) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 300 per 1000 | 51 per 1000 (6 to 354) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (10 to 590) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory;CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; CI: confidence interval; MADS: Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Schedule; RR: risk ratio; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ unblinded for subjective outcome, poor reporting for those who left early. 2Indirectness: rated 'very serious' ‐ measure reported self worth rather than social functioning. 3Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ small trial, wide confidence intervals. 4Indirectness: rated 'very serious' ‐ leaving study may not be adverse effect or event. Reasons for attrition not reported.

Background

Description of the condition

Delusional disorders are considered by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10) to be "a variety of disorders in which long‐standing delusions constitute the only, or the most conspicuous, clinical characteristic and which cannot be classified as organic, schizophrenic or affective." (World Health Organization 1992). Munro 2009 notes the characteristic "encapsulated" stable delusional system within a relatively normal personality, unlike the widespread disorganisation seen in schizophrenia.

ICD‐10 acknowledges the uncertain relationship to schizophrenia and the lack of knowledge of aetiological factors such as personality, genetics and life circumstances. The richness of variety in presentation is noted, including persecutory, hypochondriacal, grandiose, jealousy, dysmorphophobia types etc. The ICD‐10 permits the classification of the disorder even when a full blown depressive disorder is present, providing delusions persist at times when there is no disturbance of mood.

The ICD‐10 includes the following categories in the diagnosis: paranoia, paranoid psychosis, paranoid state, paraphrenia (late) and sensitiver Beziehungswahn. As well as excluding paranoid schizophrenia, it also excludes paranoid personality disorder, psychogenic paranoid psychosis and paranoid reaction. It should be noted that there are a number of classification differences between ICD‐10 and the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM‐IV(‐TR)). ICD‐10 requires three months of symptom duration, whilst DSM‐IV(‐TR) requires only one. Paraphrenia is included in ICD‐10 as a delusional disorder, whilst DSM‐IV categorises this condition under schizophrenia (Johnstone 2010).

The prevalence of DSM‐IV persistent delusional disorder has been reliably estimated at about 0.18% (Johnstone 2010), which the authors note is about six times higher than hospital data would suggest. The course of delusional disorder has been considered generally better than schizophrenia (Johnstone 2010), but its course is, nevertheless, often chronic. Munro 2009 notes that, despite therapeutic pessimism in the past, delusional disorder is highly treatable. However, if untreated, as well as causing misery to patients, it is associated with increased rates of suicide and homicide, particularly subforms such as delusional jealousy and erotomania. Munro 1999 cites murder rates in two earlier case series of delusional jealousy of 4% and 2%.

Description of the intervention

This review will consider a number of interventions commonly seen in the treatment of delusional disorder: antipsychotic medication; antidepressant medication; medication to stabilise mood and psychotherapy. A description of each type follows.

Antipsychotic medication has been considered the mainstay of treatment (Munro 2009). Historically, pimozide, a typical agent of the diphenylbutylpiperidine class, had been used preferentially. More recently, atypical antipsychotics have been used more frequently. A review by Manschrek 2006 found that most cases improved regardless of which type of antipsychotic medication (typical or atypical) was used, although they noted the limitations in the evidence base, with almost non‐existent controlled studies, but rather a body of case studies with their own methodological problems, such as positive bias and under‐reporting of negative outcomes.

Antidepressants have been commonly used in treatment; depression is commonly noted in the disorder, and perhaps following treatment by antipsychotic medication (Munro 2009). This review will consider antidepressants of all classes.

Mood stabilisers are less commonly used in the treatment of delusional disorder, but will be considered, as they are commonly used in the treatment of a number of other chronic psychiatric disorders.

Psychotherapy (of a variety of subtypes) will be considered in this review, given their common use in psychiatric practice.

How the intervention might work

Antipsychotic medication is known to exert antagonist effects on a number of neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine and glutamate. Varying effects are produced, depending on the receptor target. Common associated side effects for older agents include extra pyramidal side effects, with more recent atypical agents having a greater propensity to cause metabolic side effects. Other noted side effects include anticholinergic and antihistaminergic effects.

The precise mechanisms by which other treatments (antidepressants, mood stabilisers and psychotherapy) might work are not clear. As noted above, depression may accompany delusional disorder and these treatments are commonly used then; for example, psychotherapy may challenge cognitive errors and help in rehabilitation.

Why it is important to do this review

This review examines the evidence for the effectiveness of treatments in delusional disorder. We are unaware of any systematic reviews covering the breadth of treatments in this area. Delusional disorder is relatively common and causes considerable distress for those afflicted, their families, carers and society as a whole.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of medication (antipsychotic medication, antidepressants, mood stabilisers) and psychotherapy, in comparison with placebo in delusional disorder.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials. If trials were described as 'double‐blind' but implied randomisation, we included them in a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis). If their inclusion did result in important, clinically significant but not necessarily statistically significant, differences we did not add the data from these lower quality studies to the results of the better trials, but presented such data within a subcategory. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by alternate days of the week. Where people were given additional treatments within an antipsychotic or antidepressant or mood stabiliser or psychotherapy trial, we only included data if the adjunct treatment was evenly distributed between groups and it was only the antipsychotic or antidepressant or mood stabiliser or psychotherapy trial that was randomised.

Types of participants

Adults, however defined, with delusional disorder, again by any means of diagnosis.

We were interested in making sure that information was as relevant to the current care of people with delusional disorder as possible, so we proposed to highlight clearly the current clinical state (acute, early post‐acute, partial remission, remission) as well as the stage (prodromal, first episode, early illness, persistent) and whether the studies primarily focused on people with particular problems (for example, treatment‐resistant illnesses).

Types of interventions

1. Antipsychotic medication

Any dose and mode or pattern of administration. This included older antipsychotic medication ('typical') as well as more recent 'atypical' antipsychotic medication.

2. Antidepressant medication

Any dose and mode or pattern of administration. This included antidepressants of whichever class, from older tricyclic types to more recent types such as SSRIs (serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors).

3. Mood stabilisers

This is a broad class of medication with differing modes of putative mechanism. Common types of these agents, more frequently used in bipolar disorder, include lithium, sodium valproate, carbamazepine and lamotrigine. Latterly, antipsychotic medications are used for a similar purpose, but for the purposes of this review are considered separately as antipsychotic medication.

4. Psychotherapy

Any form of psychotherapy (e.g. from cognitive behavioural therapy to psychodynamic), whether individual or group, of varying durations (from short‐term to long‐term).

5. Placebo, no treatment, standard care

This included placebo treatments and no treatment, or a standard care group when this is provided for all.

Types of outcome measures

As delusional disorder is potentially a long‐term condition, we considered outcomes with respect to the long term as well as the short term. We divided all outcomes into short‐term (less than six months), medium‐term (seven to 12 months) and long‐term (over one year).

Primary outcomes

1. Global state

Clinical response as defined by the individual studies (e.g. global impression of much improved, or more than 50% improvement on a rating scale).

2. Social function

Substantial improvement in target function, as defined by authors (e.g. return to gainful employment).

3. Reduction in significant risks

Reduction in significant risk as defined by the authors (e.g. reduction in rates of suicide, homicide, violence (such as against partner in delusional jealousy, or victim in erotomania)).

Secondary outcomes

1. Global state

1.1 Relapse ‐ as defined by the study 1.2 Average score/change in global state

2. Social functioning

2.1 Clinically significant response in social functioning ‐ as defined by each of the studies 2.2 Average score/change in social functioning

3. Service utilisation

3.1 Hospital admission 3.2 Days in hospital

4. Leaving the study early

4.1 For any reason 4.2 Due to adverse effect

5. Mental state

5.1 Clinically significant response in mental state ‐ as defined by each of the studies 5.2 Average score/change in the mental state 5.3 Clinically significant response on delusional symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 5.4 Average score/change in delusional symptoms 5.5 Clinically significant response on depressive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 5.6 Average score/change in depressive symptoms

6. Behaviour

6.1 Clinically significant response in behaviour ‐ as defined of the studies 6.2 Average score/change in behaviour 6.3 Violence against others

7. Adverse effects/event

7.1 Specific ‐ death ‐ suicide or natural causes, homicide (e.g. delusional jealousy ‐ against partner/others) 7.2 Specific ‐ extrapyramidal effects ‐ incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs 7.3 Specific ‐ extrapyramidal effects ‐ clinically significant effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies 7.4 Specific ‐ extrapyramidal effects ‐ average score/change 7.5 Specific ‐ cardiac effects 7.6 Specific ‐ anticholinergic effects 7.7 Specific ‐ antihistamine effects 7.8 Specific ‐ prolactin‐related symptoms

8. Economic outcomes

9. Quality of life/satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or carers

9.1 Significant change in quality of life/satisfaction ‐ as defined by each of the studies 9.2 Average score/change in quality of life/satisfaction 9.3 Employment status

10. Cognitive functioning

10.1 Significant change in cognitive function ‐ as defined by each of the studies 10.2 Average score/change in cognitive function

'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008), and we used GRADE profiler (GRADEpro) to import data from RevMan 5 (Review Manager) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rate as important to patient care and decision making. We aimed to select the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Global state ‐ clinically important response

Mental state: delusional symptoms ‐ clinically important response

Mental state: depressive symptoms ‐ clinically important response

Service utilisation ‐ admission

Social functioning ‐ substantial improvement in target function, as defined by authors (e.g. return to gainful employment)

Adverse effect/event ‐ clinically important adverse effect/event

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register

We searched the register in February 2012 using the phrases:

[(*delusional disorder* OR *paranoia* OR *paranoid psychosis* OR *paranoid state* OR *paraphrenia* OR *sensitiver Beziehungswahn* OR *erotomania* OR *de clerambault syndrome* OR *delusional jealousy* OR *othello syndrome* in title, abstract, index terms of REFERENCE) or (*delusional disorder* in health care conditions of STUDY]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches and conference proceedings. For details of the databases searched, see group module.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected the references of all identified studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors MS and ST independently inspected citations from the searches and identified relevant abstracts. WK independently re‐inspected a random 20% sample to ensure reliability. Where disputes arose, we acquired the full report for more detailed scrutiny. MS and ST obtained and inspected full reports of the abstracts meeting the review criteria. Again, WK re‐inspected a random 20% of reports in order to ensure reliable selection. Where it was not possible to resolve disagreement by discussion, we attempted to contact the authors of the study for clarification. We obtained information from a number of authors, which facilitated this process, such as from Farhall 2009, Fear 2002, O'Connor 2007 and Nordentoft 2009. We did attempt to contact the authors of Çetin 2000, but did not receive a reply.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

Review authors MS and ST extracted data from the included study. In addition, to ensure reliability, WK independently extracted data from the included study. We discussed any disagreement, documented decisions and contacted the author of the included study for clarification of any issues. With the remaining problems, CEA helped clarify issues. We extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible, but only included the data if two review authors independently had the same result. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto a standard, simple form.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if:

the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and

the measuring instrument had not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial.

Ideally, the measuring instrument should have been either i. a self report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realised that this is not often reported clearly, therefore we noted if this was the case or not in 'Description of studies'.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions such as delusional disorder. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We combined endpoint and change data in the analysis and we used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Higgins 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion: a) standard deviations (SDs) and means are reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors; b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the SD, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution) (Altman 1996); c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which can have values from 30 to 210), we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐S min), where S is the mean score and S min is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and endpoint and these rules can be applied. When continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. We entered skewed data from the included study of fewer than 200 participants into additional tables rather than into an analysis. Skewed data poses less of a problem in large samples of more than 200; if we had samples of that size or greater, we would have entered that data into the syntheses.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

If relevant data were available, we would have converted continuous outcome measures to dichotomous data. This could be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It was generally assumed that if there was a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we would have used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

We intended to enter data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for the intervention CBT. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'Not un‐improved'), we reported data where the left of the line indicated an unfavourable outcome. This was noted in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

MS, ST and WK worked independently to assess risk of bias by using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assess trial quality (Higgins 2011). This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article, such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

If the raters disagreed, we made the final rating by consensus. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of the included trial were provided, we contacted the authors of the study to obtain further information. We would have reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment, but if disputes arose as to which category a trial was to be allocated, again, resolution was to be made by discussion.

We noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive than odds ratios (Boissel 1999), and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000).

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we estimated the MD between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (SMD).

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992), whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

If we had included cluster studies, where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we would have presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. We would have contacted first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients for their clustered data and adjusted for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it would have been assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed, taking into account intra‐class correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we would only have used data of the first phase of cross‐over studies; however the included study was not a cross‐over trial.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in the comparisons. If data were binary, we simply added and combined them within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in Chapter 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not present these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not present these data or use them within analyses (except for the outcome 'leaving the study early'). If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we would have marked such data with (*) to indicate that such a result may well be prone to bias. The included trial did not have more than 50% data loss and so this was not necessary.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). Those leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes we used the rate of those who stay in the study ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ for those who did not. We undertook a sensitivity analysis testing how prone the primary outcomes were to change when data only from people who completed the study to that point were compared to the intention‐to‐treat analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and data only from people who completed the study to that point were reported, we presented these data.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we tried first to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals (CIs) were available for group means, and either the P value or t value were available for differences in mean, we could calculate them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). When only the SE was reported, we calculated SDs by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 presented detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, CIs, ranges or other statistics (Higgins 2011). If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method, which was based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies could introduce error, the alternative would have been to exclude a given study's outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, where LOCF data were used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data had been assumed, we presented these data and indicated that they were the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

If we had found more than one study we would have considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We would have inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations that we had not predicted would arise. If such situations or participant groups arose, we would have fully discussed these.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

If we had found more than one stude we would have considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We would have inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods that we had not predicted would arise. If such methodological outliers arose, we would have fully discussed these.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We would have visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We would have investigated, if relevant, heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 statistic alongside the Chi2 test P value. The I2 statistic provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. the magnitude and direction of effects and ii. the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi2 test, or confidence interval for I2). We would have interpreted an I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 test as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Chapter 9.5.2 ‐ Higgins 2011). If we had found substantial levels of heterogeneity in the primary outcome, we would have explored reasons for the heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

1. Protocol versus full study

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in Chapter 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We tried to locate a protocol for the included randomised trial. If the protocol had been available, we would have compared the outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. As the protocol was not available, we compared the outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with the reported results.

2. Funnel plot

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are again described in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases, but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes as only one study was included. In other cases, where funnel plots were possible, we would have sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model. It puts added weight onto small studies, which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose a fixed‐effect model for all analyses. The reader is, however, able to choose to inspect the data using the random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

We did not conduct subgroup analyses as we anticipated there would be insufficient data.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, we reported this. First, we would have investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we would have visually inspected the graph and removed outlying studies to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review, we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, we would present the data. If not, we would not have pooled the data but discussed the issues. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off but are investigating use of prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity was obvious, we would have simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not undertake analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes, we would have included these studies and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were added to those with better description of randomisation, then we would have employed all data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption/s and when we used data only from people who complete the study to that point. If there was a substantial difference, we reported the results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SD data (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption/s and when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. We would have undertaken a sensitivity analysis testing how prone the results were to change when completer‐only data only were compared to the imputed data using the above assumption. If there had been a substantial difference, we would have reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that we judged to be at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (implied as randomised with no further details available), allocation concealment, blinding and outcome reporting for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome. If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias had not substantially altered the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we would have included the data from these trials in the analysis.

4. Imputed values

We would also have undertaken a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster‐randomised trials.

If substantial differences had been noted in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we would not have pooled data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but would have presented them separately.

5. Fixed‐effect and random‐effects

We synthesised all data using a random‐effects model, however, we also synthesised data for the primary outcome using a fixed‐effect model to evaluate whether this altered the significance of the result.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies. These tables contain detailed descriptions of the relevant studies.

Results of the search

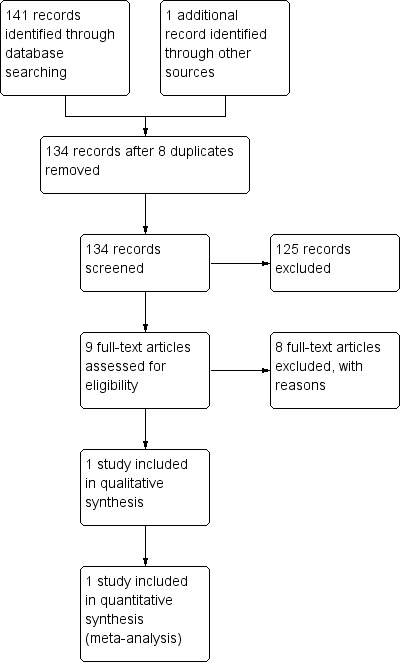

The initial search yielded 141 citations. We were able to include only one study from this. Common reasons to exclude studies included trials not being complete and lack of separate subgroup analyses of delusional disorder patients in trials of larger groups of psychotic patients. We have given information on eight studies that were among those studies excluded, which we think will be of interest to the reader. For details of trial selection see Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We have included one study that met our criteria. This is O'Connor 2007, which we have described below in detail. This is a small randomised controlled trial comparing adjunctive CBT to supportive psychotherapy for people with delusional disorder, most already receiving medication. This study included in total 24 people. We could not find any additional studies to include.

1. Length of trial

The trial was of 24 weeks duration.

2. Participants

This trial was for people with delusional disorder, as defined by DSM‐IV. No healthy controls were used. The study appeared implicitly to have used outpatients, based on the description of patients' level of function, although this was not made explicit. Participants were described as not being markedly impaired in function, apart from the impact of the delusion (although this was not described). Fifteen of the 17 completers were stabilised on psychotropic medication and were stable with no change in symptoms for two months preceding the study. All medication was continued unchanged during the study period. Antidepressants, antipsychotics and benzodiazepines were recorded as having been used.

3. Setting

Participants met with a therapist; this is likely to have been in a hospital or outpatient setting.

4. Study size

The study size was small; there were 17 completers from an initial sample size of 24.

5. Interventions

This study assessed an augmenting psychotherapeutic intervention, comparing CBT to supportive psychotherapy, which the authors described as an attention placebo control (O'Connor 2007). In both interventions, patients were mostly already taking medication: antipsychotics, antidepressants and benzodiazepines; however, individual regimes were not given and this was continued during the trial ‐ this was the case for 15 of 17 completers.

The CBT and supportive psychotherapy were delivered within individual weekly meetings with one of three licensed psychologists specialised in CBT for delusional disorder, of equal time and number, over 24 weeks. The CBT programme was described as being based on programmes found in the literature and followed the main stages of preparation, cognitive challenge and reality testing. The supportive psychotherapy involved discussion of immediate problems and recurrent themes in a non‐directive and supportive manner, and was described as encapsulating a supportive psychotherapeutic approach. It controlled for time, number of therapeutic encounters and non‐specific supportive effects of therapy. Participants in the attention placebo control also completed the daily diary and the subscales of assessment.

6. Outcomes

We were able to extract the following outcomes from the included study, O'Connor 2007: leaving the study early and self worth. Other data were skewed, including other mental state data.

6.1 Mental state: scales

O'Connor 2007 used the Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Schedule (MADS) as its primary outcome; it also measured outcomes using the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the Social Self‐Esteem Inventory, but we were unable to use data from these scales.

6.1.1 Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Schedule (MADS) (Taylor 1994)

This is a 53‐item, clinician‐rated scale to elicit delusional phenomenology (O'Connor 2007). It is divided into eight dimensions, ranging from strength of conviction to insight. It was conceived as a research tool and was not originally validated for clinical interpretation.

6.2.2 Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS) (Eisen 1998)

This is a clinician‐administered, seven‐item scale to assess delusions across a range of psychiatric disorders. Its authors noted that whilst it had excellent reliability for total score and individual item scores, it was not correlated to symptom severity, although it was correlated with other measures of insight.

6.2.3 Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1979)

The BDI is a 21‐point scale that measures depression symptoms and severity in people over the age of 13. The range of item types includes cognitive, affective, somatic and vegetative symptoms of depression (Smarr 2003).

6.2.4 Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1988)

The BAI is a 21‐item, self report inventory for measuring the severity of anxiety in psychiatric populations.

6.2.5 Social Self‐Esteem Inventory (Lawson 1979)

This is a 30‐item measure of self esteem in social situations. It may only be weakly correlated with social function, but may also reflect mental state.

6.2 Missing outcomes

Data were not available for global state, social functioning, service utilisation, behaviour, adverse effects/events, economic outcomes or cognitive functioning.

7. Awaiting assessment

No studies are awaiting assessment.

8. Ongoing studies

As far as we are aware, the only ongoing study that may be relevant is the ACTION trial, and further details may be found in Characteristics of ongoing studies. From personal contact, the Nordentoft 2009 study group indicated that they may analyse study data on delusional disorder.

Excluded studies

We have excluded eight studies ‐ please see Characteristics of excluded studies. For seven of these, there was no separate subgroup analysis of participants with delusional disorder. For the other study, Çetin 2000, there was insufficient information to extract useful data.

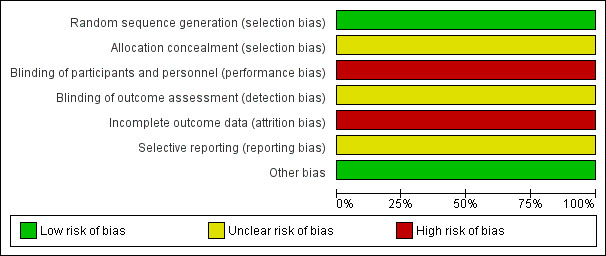

Risk of bias in included studies

Further details of risk of bias can be found in Characteristics of included studies, as well as below, and a summary of the risk of bias is shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The included trial was described by the authors as randomised. O'Connor 2007 stated that participants were randomly allocated by consecutive referral at point of entry into the study. Personal communication clarified that this was performed using a random number table. No description was made of concealment steps. We consider this a low risk of bias.

Blinding

O'Connor 2007 did not describe any blinding methodology and by its nature would have been unblinded as therapists would have been aware of which intervention they were delivering, and patients may have been aware also (if, for example, they had knowledge of CBT or past treatment). This is a high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

O'Connor 2007 did not report adequate data regarding people who left early. Of the 24 people randomised, one person withdrew early from the CBT arm (refused treatment) and from the attention placebo control arm, six people withdrew early. Data were only analysed for those who completed, i.e. not on an intention‐to‐treat basis. This is a high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

We detected some selective reporting in the included study, with some imbalance to focus on positive findings and minimise negative results. The risk of bias is unclear.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not detect any other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison 1: Adjunct cognitive behavioural therapy versus adjunct supportive psychotherapy (both with standard medication)

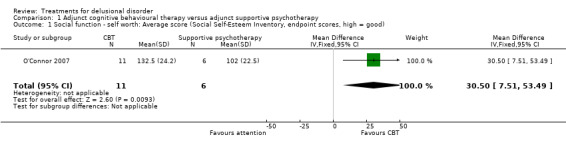

1.1 Social function ‐ self worth: average score (Social Self‐Esteem Inventory, endpoint scores, high = good)

For this outcome we only found one relevant trial (n = 17) (O'Connor 2007). There was a statistically significant difference between cognitive behavioural therapy and attention (both with standard medication) (mean difference (MD) 30.5, confidence interval (CI) 7.51 to 53.49, Analysis 1.1). The scale used, the Social Self‐Esteem Inventory is, however, only a measure of self worth in social situations and may thus not be well correlated to social function, though it may reflect mental state.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adjunct cognitive behavioural therapy versus adjunct supportive psychotherapy, Outcome 1 Social function ‐ self worth: Average score (Social Self‐Esteem Inventory, endpoint scores, high = good).

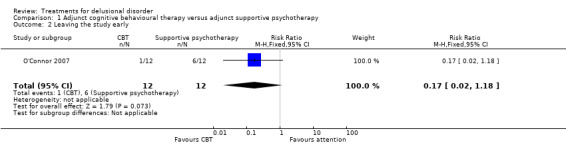

1.2 Leaving the study early

For this outcome we only found one relevant trial (n = 24) (O'Connor 2007). There was no significant difference between cognitive behavioural therapy and attention (both with standard medication) (risk ratio (RR) 0.17, CI 0.02 to 1.18, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adjunct cognitive behavioural therapy versus adjunct supportive psychotherapy, Outcome 2 Leaving the study early.

1.3 Mental state: 1a. Average score ‐ specific (Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Schedule (MADS), endpoint data, low = good, skewed data)

Results were skewed and are best interpreted by inspecting Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adjunct cognitive behavioural therapy versus adjunct supportive psychotherapy, Outcome 3 Mental state: 1a. Average score ‐ specific (MADS, endpoint data, low = good, skewed data).

| Mental state: 1a. Average score ‐ specific (MADS, endpoint data, low = good, skewed data) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N |

| Strength of conviction | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 54.6 | 33.0 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 66.0 | 34.4 | 6 |

| Belief maintenance | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 0.6 | 0.2 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 0.7 | 0.3 | 6 |

| Affect relating to belief | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 0.5 | 0.2 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 0.6 | 0.2 | 6 |

| Positive actions on belief | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 0.4 | 0.2 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 0.5 | 0.2 | 6 |

| Idiosyncrasy of belief | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 0.9 | 0.6 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 1.1 | 0.6 | 6 |

| Preoccupation with belief | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 1.7 | 1.0 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 2.2 | 0.8 | 6 |

| Systematisation of belief | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 1.5 | 1.2 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 2.0 | 1.0 | 6 |

| Insight | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 0.9 | 0.8 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 0.9 | 0.7 | 6 |

1.4 Mental state: 1b. Average score ‐ specific (endpoint scores; low = good, skewed data)

Results were skewed and are best interpreted by inspecting Analysis 1.4.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adjunct cognitive behavioural therapy versus adjunct supportive psychotherapy, Outcome 4 Mental state: 1b. Average score ‐ specific (various scales, endpoint scores; low = good, skewed data).

| Mental state: 1b. Average score ‐ specific (various scales, endpoint scores; low = good, skewed data) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N |

| Depression (BDI) | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 12.0 | 14.4 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 18.3 | 7.8 | 6 |

| Anxiety (BAI) | ||||

| O'Connor 2007 | CBT | 16.1 | 14.6 | 11 |

| O'Connor 2007 | Attention 'placebo' | 14.0 | 14.2 | 6 |

Discussion

Summary of main results

1. General: Psychopharmacological treatments

We did not find any randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to include in this review to provide evidence on the effectiveness of psychopharmacological treatments for people with delusional disorder. It is particularly notable that we could not find any RCT on pimozide for delusional disorder, as this medication has been advocated in the past as having particular efficacy. We could not find any evidence that newer antipsychotic medication (atypicals) were any better or worse than older medication (typicals).

2. Comparison 1: Adjunct cognitive behavioural therapy versus adjunct supportive psychotherapy

We found only one RCT, on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which met our inclusion criteria ‐ see O'Connor 2007 (Table 1). This compared adjunctive CBT to supportive psychotherapy. It is also worth noting that this was an augmentation study, with most patients taking a variety of medications. Whilst there are limitations in how far the results from this small study of 24 people (17 participants completed) can be generalised, we highlight relevant outcomes below. Outcomes were only available on social function ‐ self worth, leaving the study early and mental state.

2.1 Social function ‐ self worth

O'Connor 2007 found an effect favouring CBT although the small number of participants makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions (Analysis 1.1). The scale used, the Social Self‐Esteem Inventory is, however, only a measure of self worth in social situations and may thus not be well correlated to social function, though it may reflect mental state.

2.2 Leaving the study early

In O'Connor 2007, one person out of 12 in the CBT arm left the study, compared to six of 12 in the placebo arm. This was, however, a relatively weak effect due to the low statistical power of the study, with confidence intervals crossing the line of equivalence (see Analysis 1.2), and it would be premature to draw conclusions from this.

2.3 Mental state

Unfortunately there were no global state outcomes that could be drawn from O'Connor 2007, but there were a number of secondary outcomes for which some data were available: see Analysis 1.3 and Analysis 1.4. These suggested some improvement in mental state on a number of scales such as the Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Schedule (MADS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), but the data were too skewed to draw firm conclusions and, moreover, the sample size was small. Please see Table 1.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Overall, the included study comprises 17 people who completed the trial. This is too low a number to allow generalisation of the results to the population of people with delusional disorder.

The data presented were of variable quality(see Table 1). There was little description of those people who withdrew from the trial early, nor were their results accounted for. For the results presented, O'Connor 2007 did not present data that were meaningful to many of the clinical outcomes that we set out in our protocol. Furthermore, there may be some underlying confounding effects due to the fact that 15 of the 17 completers were taking medication of varying types as this was an augmentation study.

Quality of the evidence

See Included studies for a description of the strengths and weaknesses of O'Connor 2007. Whilst this study was well designed in many respects, its key weakness is that the data presented do not cover meaningful clinical global outcomes.

Potential biases in the review process

We adhered to our protocol. We met and discussed differences of opinion regarding results. One potential bias was that foreign language studies may not have been identified by the search process, which was in English (although the search did show one article in Chinese). Whilst it is possible, we consider it unlikely that there would be substantial studies in foreign languages on this question and the conclusions remain robust.

We are also aware that the search date for this review is over three years old. We intend to update this as soon as possible post publication.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We are unaware of any published systematic reviews addressing treatments for delusional disorder. A number of reviews, case reports and books have been published examining the area. We consider a number of prominent ones below, in the context of our findings.

Fear 2013 is a review of developments in the management of delusional disorders. The author considers that the evidence mainly consists of case‐based reports and notes the need for further trials, in agreement with our findings. The author nevertheless does make recommendations for the use of atypical antipsychotic medication in preference to typical antipsychotics, which we could find no evidence for in our review, nor in other large, independent, publicly funded trials comparing antipsychotic types, such as CATIE 2005. The author also states that cognitive therapy has been shown to be beneficial; however, we could only find limited weak evidence to support this.

Manschrek 2006 is a review of treatments in delusional disorder. They found data on 134 cases and concluded that antipsychotic medication (of any type) was effective in over 50% of cases. The authors do suggest that the success rate may be an overestimation due to publication bias and a paucity of RCTs (they did not state that they had identified any). Their assertion that delusional disorder should not be considered a treatment‐resistant condition is in agreement with the limited RCT evidence from this review.

Munro 2009 is a book that synthesises the author's extensive experience in researching and treating delusional disorders. The author recommends pimozide as a first‐line antipsychotic medication but also notes that other antipsychotic medications have had some efficacy in other cases studies. We did not find any RCTs for pimozide and also noted that in the review by Manschrek 2006 above pimozide had been found to be less efficacious than other antipsychotics. As both reviews were based on case reports, with methodological limitations, this is inconclusive. Munro also advised that there may be a place for CBT in modifying, but not treating, delusional disorder. The study of O'Connor 2007 suggests that modification of some elements is possible, albeit not full resolution. Finally, Munro suggests that post‐psychotic depression may commonly arise where patients with delusional disorder are treated with antipsychotic medication. He suggests treatment with an antidepressant in addition to the antipsychotic. We did not find any RCT that we could include to assess this.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For people with delusional disorder

People who have delusional disorder may mistrust treatment due to their underlying condition. It would seem that the chance of trusting healthcare professionals and their treatments is further undermined by the lack of evidence for fairly tested treatments. People with delusional disorder, if not dangerous to others, may have a powerful argument to request treatment within a randomised trial with meaningful outcomes.

2. For clinicians

There is a lack of evidence for any treatment and interventions are therefore given because of clinical experience and goodwill rather than clear fair testing. Delusional disorder is a psychotic disorder, therefore it seems reasonable to apply similar treatments used in other psychotic conditions until such evidence is found.

3. For funders and managers

The limited evidence that we obtained is not generalisable to the population of people with delusional disorder. We could not find any trial comparing medication to placebo. We found only one trial comparing CBT to placebo. The numbers involved were low (17 completers) and it is difficult to generalise using the results available, especially as the data did not address meaningful clinical outcomes, were skewed in nature and were from a small sample size. Patients were also concurrently taking medication, which may confound the results.

Implications for research.

1. General

The studies we identified were pioneering and important. If their findings had been more clearly reported, as is now recommended by the CONSORT statements (Begg 1996; Moher 2001), this review would have had more findings to report. Continuous data should be presented with standard deviations. With the AllTrials campaign, perhaps one day more data will become available, even from the old studies identified in this review.

2. Specific

There is a clear need for randomised controlled trials to examine treatments for patients with delusional disorder. The included study, O'Connor 2007, does show that it is possible to conduct randomised trials for people with delusional disorder. Unfortunately, the area appears to have been ignored both by the psychiatry community, with an emphasis on recruiting patients with schizophrenia and/or not analysing data on delusional disorder patients, and by the psychology community, with many studies recruiting patients with psychosis, but not categorising them by psychiatric diagnosis. Until this is done, patients with delusional disorder will suffer from a lack of evidence on which treatments work and the disorder will likely continue to be under diagnosed, with few clear guidelines for people with delusional disorder and their clinicians.

2.1 Reporting issues

Evidence for treatments in delusional disorder could be gathered much more quickly if researchers separately analysed the results for people with delusional disorder, who had been recruited into larger studies. This would permit subsequent meta‐analyses to build a larger evidence base for these patients. This may prove a pragmatic approach to developing an evidence base, as single trials may be difficult to recruit to in large numbers, due to the nature of the disorder. The excluded studies on their own might have furnished a great deal of information to develop evidence on treatments in delusional disorder, had they been well reported (see Excluded studies).

At least one study, Çetin 2000, which was presented as a conference paper, could potentially have yielded useful information about psychopharmacological treatment of delusional disorder. Unfortunately the study failed to report results of its comparison of risperidone versus pimozide in full. We have tried to contact the authors regarding this study, but were unsuccessful.

Consideration must be given to the role of international classification systems. At present, both the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10) and Diagnostic Statistical Manual 5 (DSM‐5) consider delusional disorder as a separate disorder, with its own inclusion and exclusion criteria, to differentiate it from other psychoses such as schizophrenia. The symptoms, course and outcome are considered to be quite distinct. If these categories are considered to be valid, then it behoves researchers to analyse separately and disclose information on people with this condition in future research.

2.2 Specific trial

In Table 2 we make a suggestion on the potential structure of a randomised trial that could be conducted for people with delusional disorder, to aid future research.

1. Suggested design of study.

| Methods | Allocation: the randomisation process should be clearly described. Trialists should take every precaution to minimise the effect of biases by using blinded or independent raters. Intention‐to‐treat analysis is preferable: trialists should describe from which groups withdrawals came, why they occurred and what was their outcome. Duration: 6 months minimum. Setting: in an outpatient psychiatric clinic, where patients with delusional disorder are most likely to be encountered. |

| Participants | Diagnosis: people with delusional disorder. Age: all ages. Sex: men and women. N = 300*. History: to include the full range of severity of this disorder, from people who have been hospitalised in the past to never. |

| Interventions | 1. Treatment as usual + randomised to intervention (e.g. 1st generation antipsychotic medication, at low dose). N = 150.

2. Standard treatment as usual, including patient's usual antipsychotic medication (at current dose). N = 150. The above trial could be amended to address psychological therapy as an intervention and patients could be accordingly randomised to this in addition to treatment as usual, compared to usual care. |

| Outcomes | Real world clinical outcomes, e.g. global improvement, use of scales such as CGI, mental state. Service outcomes: readmission, frequency of clinic appointments. Loss to follow‐up. Functioning: including employment. Serious events: any, list. Satisfaction. Quality of life. Economic outcomes. |

| Notes | * Size of study with sufficient power to highlight ˜20% difference between groups for primary outcome. |

CGI: Clinical Global Impression Scale

Acknowledgements

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Editorial Base in Nottingham produces and maintains standard text for use in the Methods section of their reviews. We have used this text as the basis of what appears here and adapted it as required.

Thanks to Professor Clive Adams who helped clarify issues or disagreements with data extraction and provided extensive guidance throughout, and Stephanie Sampson, Claire Irving, Samantha Roberts, Lindsey Air and the editorial team at the Nottingham University Cochrane Schizophrenia Group for their guidance and support in writing this review.

The authors would like to thank Professor Alistair Munro for his helpful comments in the development of the study, based on his experience as an expert in this field, and Ibrahim Hanafi for peer reviewing this version.

The authors would like to thank Dr Chris Fear for his efforts to try and obtain the original data from his study in 2002.

We acknowledge and thank Ibrahim Hanafi for peer reviewing this version of the review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Adjunct cognitive behavioural therapy versus adjunct supportive psychotherapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Social function ‐ self worth: Average score (Social Self‐Esteem Inventory, endpoint scores, high = good) | 1 | 17 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 30.5 [7.51, 53.49] |

| 2 Leaving the study early | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.02, 1.18] |

| 3 Mental state: 1a. Average score ‐ specific (MADS, endpoint data, low = good, skewed data) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.1 Strength of conviction | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.2 Belief maintenance | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.3 Affect relating to belief | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.4 Positive actions on belief | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.5 Idiosyncrasy of belief | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.6 Preoccupation with belief | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.7 Systematisation of belief | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.8 Insight | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4 Mental state: 1b. Average score ‐ specific (various scales, endpoint scores; low = good, skewed data) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.1 Depression (BDI) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.2 Anxiety (BAI) | Other data | No numeric data |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

O'Connor 2007.

| Methods | Allocation: random. Blinding: unblinded. Duration: 24 weeks. |

|

| Participants | Diagnosis: DSM‐IV delusional disorder, confirmed by an independent rater using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM axis 1 disorders. N = 24, 17 completed. Age: mean ˜38 (completers). Sex: 8 women, 9 men (completers). History: referred by specialists in psychotic disorders, had stable symptoms for 2 months, most in receipt of psychiatric medication (not altered once trial began). It is not explicit if any hospitalised patients were included, but this can be inferred from the stability criterion that all patients were outpatients. |

|

| Interventions | 1. Cognitive behavioural therapy + standard medication care*: Quote: "The CBT consisted of individualized weekly meetings [for 24 weeks] with 1 of 3 licensed psychologists specialized in CBT for DD. The CBT program was based on programs reported in the literature and followed the main stages of preparation, cognitive challenge, and reality testing." It was manualised for the therapist

N = 12. 2. Attention 'placebo' + standard medication care*: Quote: "The APC consisted of individualized weekly meetings with 1 of 3 licensed psychologists specialized in CBT for DD. In the APC treatment, the therapist and patient discussed any immediate problems and recurrent themes in a nondirective and supportive manner, encapsulating the proper supportive psychotherapeutic approach to the paranoia patient of interested, attentive, relaxed, and unaffected attitude with an unfeigned air of detachment and suspended judgment, which has been shown to lead to some remission of symptoms.'' This was manualised for the therapist N = 12. |

|

| Outcomes | Social function ‐ self worth: Social Self‐Esteem Inventory. Leaving the study early. Unable to use: Mental state (BAI, BDI, MADS): data were skewed. Insight: authors did not fully report BABS. |

|

| Notes | * 15 of 17 completers were already taking medication; 11 of the completers were taking 1 of 3 types of antipsychotic medication (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine) and the other 6 were taking antidepressants or benzodiazepines. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Random allocation by consecutive referral at point of entry into the study per published article." We have established (via personal correspondence with the study's lead author) that random allocation occurred at the point of entry into the trial of consecutive patients through the use of a random number table (Fisher & Yates). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified in the study. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | The trial was unblinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "The main outcome measure was the MADS rating; this test was administered by an evaluator independent of the study." There is no mention that blinding was assured. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | People who withdrew early were not accounted for in the final data, only completers. The study does acknowledge the attrition rate. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | There is some unevenness in selective reporting of positive findings, with less prominence given to less positive findings, although the study does acknowledge some weaknesses overall. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other biases noted. |

BABS: The Brown Assessment of Belief scale BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory BDI: Beck Depression Inventory DSM‐IV: Diagnostic Statistical Manual IV MADS: Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Schedule

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Al Haddad 1996 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 49 people with mania, acute psychoses or exacerbation of a chronic psychosis ‐ no diagnostic information on whether anyone had delusional disorder. |

| Davies 2007 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 275 people with a DSM‐IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or delusional disorder (10). Intervention: one of a range of first‐generation antipsychotic medications versus one of a range of second‐generation antipsychotic medications. Outcome: no usable outcomes as no separate reporting of results relevant to delusional disorder presented. |

| Farhall 2009 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 94 people with a diagnosis of either schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder (6) or mood disorder with psychotic features. Intervention: CBT for psychosis + TAU (treatment as usual including, for most, antipsychotic medication) versus TAU (treatment as usual including, for most, antipsychotic medication). Outcome: no usable outcomes as no separate reporting of results relevant to delusional disorder presented. |

| Fear 2002 | Allocation: randomised, cross‐over. Diagnosis: DSM‐IV delusional disorder. Interventions: risperidone versus placebo, N = 4. Outcomes: mental state (BPRS, MADS, PANSS), leaving the study early ‐ no usable data, reported as case report of 1 person ‐ study closed because of poor recruitment. Dr Fear contacted and kindly attempted to obtain original data, but this was not possible. |

| Foster 2010 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 21 people with schizophrenia and 3 with a diagnosis of either schizoaffective disorder or delusional disorder. Intervention: W‐CBT (cognitive behavioural worry intervention) + standard medical care* versus TAU. Outcome: no usable outcomes as no separate reporting of results relevant to delusional disorder presented. *Inferred that W‐CBT was in addition to standard medical care including medication as no description of medication regimes being stopped etc. |